Abstract

Gordon Holmes syndrome (GHS) is a rare Mendelian neurodegenerative disorder characterized by ataxia and hypogonadism. Recently, it was suggested that disordered ubiquitination underlies GHS though the discovery of exome mutations in the E3 ligase RNF216 and deubiquitinase OTUD4. We performed exome sequencing in a family with two of three siblings afflicted with ataxia and hypogonadism and identified a homozygous mutation in STUB1 (NM_005861) c.737C→T, p.Thr246Met, a gene that encodes the protein CHIP (C-terminus of HSC70-interacting protein). CHIP plays a central role in regulating protein quality control, in part through its ability to function as an E3 ligase. Loss of CHIP function has long been associated with protein misfolding and aggregation in several genetic mouse models of neurodegenerative disorders; however, a role for CHIP in human neurological disease has yet to be identified. Introduction of the Thr246Met mutation into CHIP results in a loss of ubiquitin ligase activity measured directly using recombinant proteins as well as in cell culture models. Loss of CHIP function in mice resulted in behavioral and reproductive impairments that mimic human ataxia and hypogonadism. We conclude that GHS can be caused by a loss-of-function mutation in CHIP. Our findings further highlight the role of disordered ubiquitination and protein quality control in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disease and demonstrate the utility of combining whole-exome sequencing with molecular analyses and animal models to define causal disease polymorphisms.

INTRODUCTION

Gordon Holmes syndrome (GHS [MIM 212840]) is a rare neurodegenerative disorder characterized by ataxia with hypogonadism (1). Despite almost 100 years of clinical recognition, there is still little understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms or underlying genetic causes of GHS. Recently, mutations in the E3 ligase RNF216 and deubiquitinase OTUD4 were associated with GHS in multiple non-Asian families (2), suggesting that disordered ubiquitination plays an essential role in the pathophysiology of ataxia and hypogonadism.

Protein ubiquitination is primarily regulated through E3 ligases that construct covalently linked polyubiquitin chains on protein substrates, subsequently resulting in the targeting of ubiquitinated proteins for degradation through the 26S proteasome. C-terminus of HSC70-interacting protein (CHIP) is a 35-kDa protein that functions as both a molecular cochaperone, autonomous chaperone and ubiquitin E3 ligase (3–6). In cooperation with heat shock chaperone proteins, including HSC70, HSP70 and HSP90, CHIP plays a crucial role in recognizing and modulating the degradation of numerous chaperone-bound proteins. In genetic mouse models of neurodegenerative disease, the loss of CHIP function is associated with the misfolding and aggregation of several proteins (such as expanded polyglutamine tracts, hyperphosphorylated Tau and oligomeric forms of α-synuclein), all of which are thought to be associated with multiple neurodegenerative disorders such as Spinocerebellar ataxia, Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease (7–9). However, mutations in the human STUB1 gene have not been reported, and information about the physiology of CHIP deficiency in humans is non-existent. Using exome sequencing, we identified a STUB1 mutation in two patients from a pedigree that presented with GHS. We demonstrate that the STUB1 mutation leads to a loss in function of CHIP resulting in diminished E3 ligase activity; furthermore, mice lacking the expression of CHIP phenocopy some aspects of human GHS, supporting a direct link between CHIP and GHS pathophysiology.

RESULTS

Clinical assessment of two sisters with GHS

We initially observed a pedigree characterized by ataxia with hypogonadism in two sisters (II-1 and II-2) with an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern. The initial behavioral and sexual development of the proband (II-1) appeared normal, but unsteady gait developed when she was 19 years old, followed by dysarthria 2 years later and remarkable ataxia (Table 1). Upon neurological examination, Patient II-1 exhibited horizontal gaze-evoked nystagmus with no restriction of extraocular movement. Photography and fluoresce angiogram of the ocular fundus revealed no abnormality (data not shown). Additionally, muscle tone, power and deep tendon reflexes of the four limbs were normal without any overt pathology. Neuroelectrophysiological examination was generally normal, except for decreased amplitude of motor-evoked potential in the bilateral lower limbs.

Table 1.

Clinical phenotypes of STUB1 genotypes

| Subject | II-1 | II-2 |

|---|---|---|

| Ataxia | ||

| SARA | 13 | 15 |

| Cognitive measures | ||

| MMSE | 25 | 27 |

| MoCA | 11 | 24 |

| Sexual development | ||

| Tanner stage | II–III | II–III |

| Corpus uterus (mm) | 35 × 31 × 25 | 28 × 20 × 19 |

| Cervix (mm) | 23 | 16 |

| Ovaries (mm) | 14 × 9 | 13 × 10 |

| Hypogonadism | ||

| Estradiol (pg/ml) | 26 | 28 |

| Progesterone (ng/ml) | 0.31 | 0.33 |

| FSH (mIU/ml) | 6.97 | 6.25 |

| LH (mIU/ml) | 5.95 | 6.44 |

FSH, follicle-stimulating hormon; LH, luteinizing hormone.

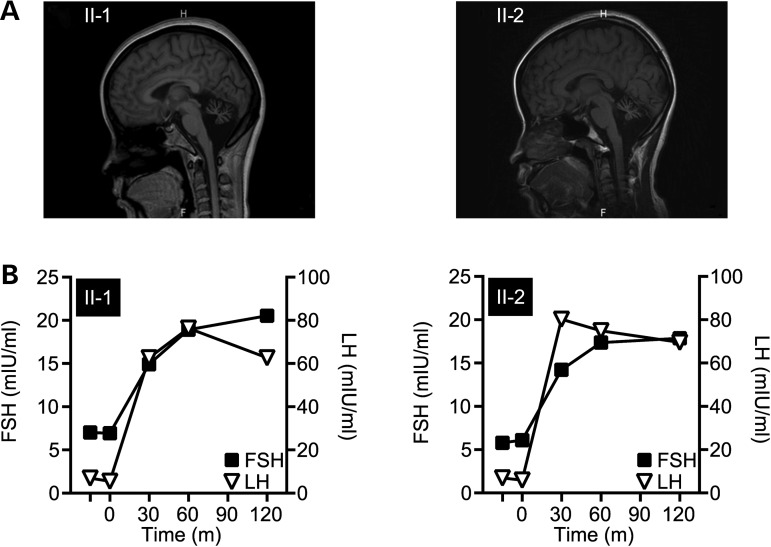

The younger sister (II-2) also had a similar illness recognized at 17 years of age with a progressive deterioration of balance and gait disturbance (Table 1). Over the next 2 years, Patient II-2 developed noticeable hand tremors during activity along with coarse head tremors. Further examination revealed findings similar to Patient II-1, in addition to increased tendon reflex and positive pathological signs in the four limbs, suggesting pyramidal tract lesions. Patients II-1 and II-2 were administered the mini-mental state examination (MMSE) resulting in normal cognitive scores, whereas the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), which is more sensitive to subtle cognitive defects particularly in the early stages of disease (10), did reveal cognitive deficiencies in both sisters (Table 1). Furthermore, patients II-1 and II-2 completed only 4 and 8 years of schooling, respectively. The neurological phenotype consisting of severe ataxia with selective cognitive impairments is consistent with cerebellar ataxia. The diagnosis of cerebellar ataxia was confirmed with MRI brain scans of both sisters that revealed remarkable atrophy of the cerebellum in both sisters (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Clinical manifestations in patients presenting with ataxia and hypogonadism. (A) MRI scans revealed remarkable cerebellum atrophy of Patients II-1 (left) and II-2 (right). (B) GnRH stimulation tests measured the response in circulating FSH and LH serum levels to exogenous GnRH administration (at time = 0) in Patients II-1 (left) and II-2 (right).

In addition to the neurological defects, both sisters had poor sexual organ development. At 22 years of age, Patient II-1 had still not menstruated, had poor development of secondary sexual characteristics (Table 1) and hypoplasia of uterus and ovaries, as revealed via ultrasound analysis (Table 1). Similar to her elder sister, Patient II-2 did not attained menarche or any secondary sexual characteristics, presenting with infantile uterus and ovarian development (Table 1). Along with the lack of sexual development in both patients, the serum levels of estradiol and progesterone were much lower than the normal reference range, leading to a diagnosis for both patients of hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (Table 1). In addition to the low circulating sex hormones and the lack of menses, levels of the pituitary hormones follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) in both sisters were comparable to prepubescent levels (Table 1). The nature of the hypogonadism in GHS is still not clear and may derive from either hypothalamic or pituitary hypogonadotropism (11). Interestingly, a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) stimulation test showed that the pituitaries in both patients were responsive to a single intravenous dose of GnRH (100 μg) measured by the stimulated release of FSH and LH (Fig. 1B), suggesting that the primary defect in these sisters may be due to hypothalamic versus pituitary hypogonadotropism. However, the pituitary response to GnRH in other GHS patients is reported to diminish over time, suggesting that pituitary dysfunction may still be an issue in these patients (2, 11), making it difficult to pinpoint the primary lesion of the hypogonadotropism hypogonadism in GHS. The two patients in this study were referred to a gynecological endocrinologist, and exogenous estrogen and progestin supplement therapy was administered in an attempt to construct an artificial menstrual cycle. After 3 weeks of therapy, their menarche came, demonstrating that the lack of reproductive organ maturity was due to the lack of circulating hormones.

Exome sequencing reveals a mutation in Stub1 associated with GHS

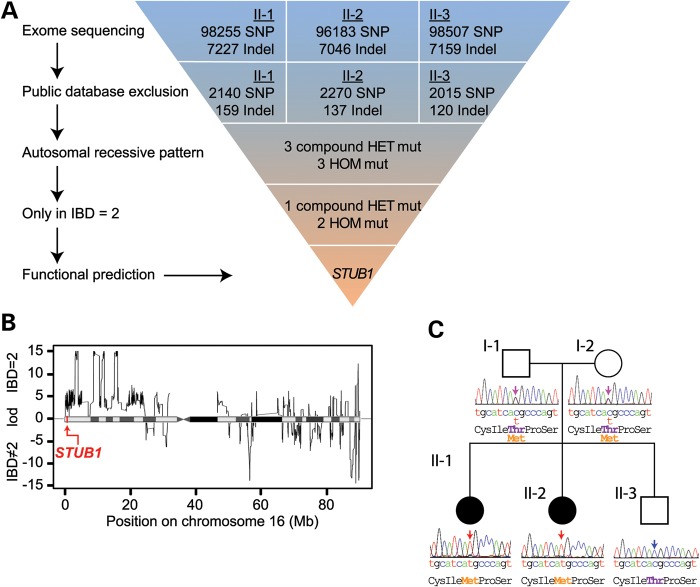

In an attempt to identify the causative mutation in this family, we performed whole-exome sequencing of the two affected patients (II-1, II-2) as well as the unaffected brother (II-3). Using a combination of bioinformatic repositories and functional algorithms, we developed a strategy to identify causal mutations segregating with the GHS phenotype (Fig. 2A). After quality control and coverage criteria were met, we started with a total of 98 255, 96 183, 98 507 SNPs, and 7227, 7046, 7159 insertions or deletions (indels) for II-1, II-2 and II-3, respectively. Since ataxia with hypogonadism is a rare disorder but has a clear phenotype, there was a low likelihood that a causal mutation in our patients was present in wider, healthy populations. We therefore filtered for novel variants by comparing our exome data to dbSNP build 132 (12), the 1000 Genomes Project (13), Hapmap (14, 15), YH project (16), and the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Exome Sequencing Project (17), further refining our target list to ∼2000 SNPs and 130 indels (Fig. 2A). Next, we filtered for a recessive inheritance pattern for variants that were present in the affected sisters, but not in the unaffected brother, which reduced the number of candidate variants to six, including three compound heterozygote variants and three homozygous variants (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Material, Table S1).

Figure 2.

Exome sequencing identifies a p.Thr246Met mutation in the GHS family. (A) Schematic representation of our exome data-filtering approach to identify mutations with recessive inheritance patterns in the family. (B) Posterior probabilities of IBD = 2 classification. The logarithmic ratio (LOD) of the posterior probabilities of being IBD = 2 versus IBD ≠ 2 are plotted for all classified variant positions on chromosome 16. A disease-causing mutation in the STUB1 gene was identified in an IBD = 2 region of high posterior probability, indicated by the red arrow. (C) A pedigree of the family indicating the unaffected (open symbols) and affected (filled symbols) members. Sanger sequencing confirmed the cosegregation of the c.737C→T resulting in p.Thr246Met mutation in STUB1 within the family.

The analysis of chromosomal regions that are identical by descent (IBD) is a form of homozygosity mapping, a fundamental tool in linkage analysis of pedigree data. For Mendelian diseases with a recessive inheritance pattern, affected family members usually share the genomic segment harboring the causal mutation. Therefore, variants inside the IBD regions found among the affected family members are of primary interest and can be exploited to identify genomic regions consistent with inheritance of a recessive monogenic disease (18, 19). These regions of interest are indicated by an IBD score of two, signifying the intersection between paternal and maternal haplotypes (19). Using the criteria of IBD = 2, we excluded three additional variants, reducing the number of candidate variants to three. Finally, we carried out functional-impact prediction on protein mutations by PolyPhen-2 (20), Mutation Taster (20) and SIFT (21). Interestingly, only one homozygous variant predicted an impact on protein function in this family, STUB1 (NM_005861) c.737C→T, resulting in a p.Thr246Met (T246M) amino acid change in the corresponding protein commonly known as CHIP (Fig. 2C). As an additional control, we tested for the STUB1 c.737C→T mutation in 500 Chinese control individuals; consistent with our data mining of multiple SNP databases used in our filtering strategy (Fig. 2A), the c.737C→T mutation was not detected in the Chinese control population.

The genetics of cerebellar ataxia has been intensely pursued over the last decade, identifying over 30 loci that associate with the disease (22). Therefore, we were not surprised that we did not detect any STUB1 mutations in an additional cohort of 32 Chinese cerebellar ataxia patients without hypogonadism, suggesting that mutations in STUB1, and the recently described mutations in RNF216/OTUD4, associate with the distinct pathophysiological phenotype of cerebellar ataxia with hypogonadism. We also sequenced the STUB1 gene in a cohort of five GHS patients that harbor a single heterozygous RNF216 mutation and eight GHS patients that do not have either RNF216 and OTUD4 mutations (2); interestingly, we did not identify any mutations in STUB1 in any of these GHS patients, suggesting that additional genetic factors likely remain to be identified in other GHS patient populations. We also performed copy number variations (CNVs) analysis and did not find any CNV that cosegregated either separately with the disease phenotype or together with single heterozygous variations in this family (23), suggesting that gene dosage was not contributing to the GHS phenotype. Taken together, our genetic and bioinformatics analyses demonstrate the association of the STUB1 c.737C→T mutation with GHS and predict the T246M in CHIP results in a functional change that directly contributes to the pathophysiology of cerebellar ataxia and hypogonadism.

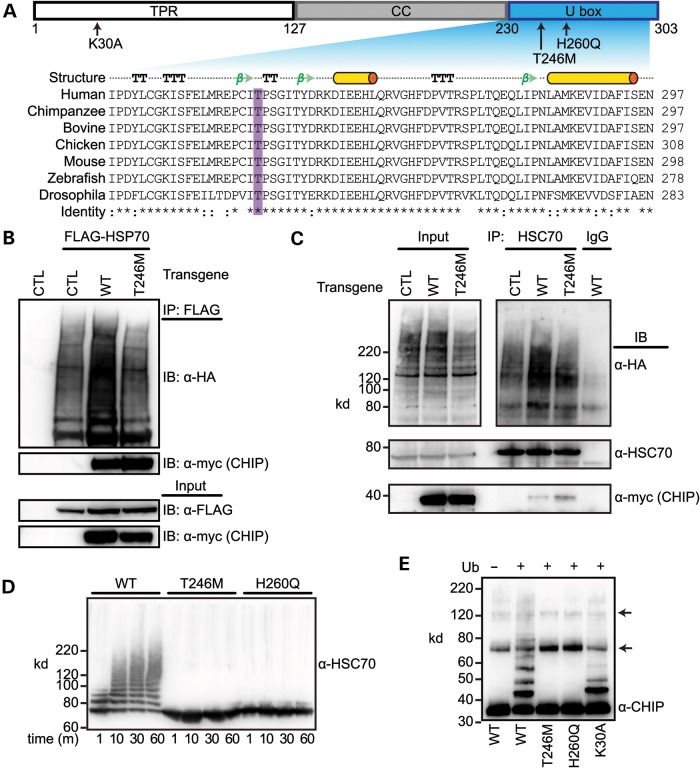

The T246M mutation in CHIP abolishes ubiquitin ligase activity

The identification of the homozygous c.737C→T mutation in sibling GHS subjects and the cosegregation of functional mutation algorithms predicting a strong impact on protein function suggested that the resulting T246M substitution mutation in CHIP results in a change in protein function. T246, which is highly conserved across CHIP homologs, is located within the U box domain of CHIP (Fig. 3A), the domain responsible for ubiquitin ligase activity (5). In addition, T246 is located in the core of a conversed beta hairpin turn (Fig. 3A) (24), likely contributing to the high impact scores of the T246M mutation identified in our functional prediction analysis (Fig. 2A). In addition to the role that CHIP plays as a ubiquitin ligase, CHIP can also act as a co-chaperone through its direct interactions with cellular chaperones including HSC70, HSP70 and HSP90 via CHIP's tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) domain (Fig. 3A) (3–5, 25). Both a functional TPR and U box domain are required for CHIP's ability to directly impact protein quality control and attenuate the cellular stress response in large part through polyubiquitiantion of HSP chaperones (26, 27). Given that the CHIP mutation identified in our patients resides in the U box domain, we hypothesized that the T246M substitution would result in a loss of CHIP's ubiquitin ligase activity, without affecting CHIP's interaction with cellular chaperones though the intact TPR domain.

Figure 3.

The T246M substitution mutation in CHIP abolishes ubiquitin ligase activity. (A) CHIP comprises three functional domains: TPR, coiled-coil (CC) and U box. The arrows indicate the location and identity of point mutations used to measure the functional parameters of CHIP (top). The structural features of the U box include alpha helices (cylinders), beta strands (arrows), beta turns (TT) and alpha turns (TTT). Sequence alignment demonstrates the evolutionary conservation of the T246 in the U box domain of the CHIP protein across the indicated species. Conservation of residues are labeled as fully conserved (*), strongly similar (:) or non-similar (). (B) COS-7 cells were co-transfected with the indicated vectors (transgenes, CTL = pcDNA3, WT = pcDNA3-CHIP, T246M = pcDNA3-CHIP-T246M) in addition to HA-tagged ubiquitin. HSP70 was immunoprecipitated (IP) with FLAG beads and the resulting precipitants and inputs were immunoblotted (IB) with the indicated antibodies. (C) COS-7 cells were co-transfected with the indicated transgenes in addition to HA-tagged ubiquitin and immunoprecipitated with either an HSC70 antibody or rat IgG. The inputs and resulting precipitants (IP) were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. Approximate molecular weights in kDa are also provided. (D and E) Cell-free ubiquitination reactions containing recombinant HSC70 and the indicated CHIP proteins resolved via SDS–PAGE and immunoblotted for an antibody recognizing HSC70 (D) or CHIP (E). Ubiquitin (Ub) was excluded in Lane 1 (E) to demonstrate the autoubiquitination of CHIP, arrows indicate the incomplete reduction of CHIP oligomers.

To test effect of the T246M substitution on CHIP's ubiquitin ligase activity and its ability to bind to chaperones, we first expressed either wild-type CHIP (CHIP-WT) or CHIP engineered with a methionine substituted for threonine at residue 246 (CHIP-T246M) in COS-7 cells. As expected, both the WT and T246M proteins immunoprecipitated with exogenous HSP70 (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Material, Fig. S1A), demonstrating that CHIP-chaperone interactions are not perturbed by the T246M substitution. In fact, more CHIP-T246M protein immunoprecipitated with HSP70 compared with CHIP-WT (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Material, Fig. S1A). Surprisingly, the increased interaction between CHIP-T246M and HSP70 did not result in robust HSP70 ubiquitination compared with CHIP-WT expressing cells (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Material, Fig. S1A), indicating that the T246M substitution deleteriously affects CHIP's ubiquitin ligase activity. We subsequently tested both the interaction and ubiquitination function of CHIP-T246M on an endogenously expressed CHIP substrate, HSC70, and again observed an increased interaction between CHIP-T246M and HSC70 with diminished polyubiquitination (Fig. 3C). Together, these data suggest that the functional defect in CHIP-T246M is a loss of ubiquitin ligase activity.

To directly test the impact of the T246M substitution on CHIP-dependent substrate ubiquitination, we compared the T246M mutation to previously engineered point mutations of CHIP. To do this, we used CHIP constructs with mutations located either in the TPR domain (CHIP-K30A) or the U box (CHIP-H260Q), which abolish either the interaction with cellular chaperones, such as HSC70 and HSP70, or the ubiquitin ligase activity of CHIP, respectively (Fig. 3A), using cell-free assays comprising purified recombinant proteins. Similar to the results observed in cell culture models (Fig. 3B and C), CHIP-T246M failed to polyubiquitinate HSC70 in vitro, mimicking the effect of the H260Q (U box) mutant CHIP protein (Fig. 3D and Supplementary Material, Fig. S2B). To confirm that the lack of chaperone ubiquitination in vitro is due to a defect in the U box domain and not due to the inability to bind to the chaperone substrate, we measured the effect of the CHIP-T246M mutation CHIP's intrinsic ability to autoubiquitinate, a phenomenon that readily occurs in vitro (27). Similar to the H260Q mutation, the CHIP-T246M mutant did not exhibit any autoubiquitination (Supplementary Material, Fig. S2B), in contrast to CHIP-WT and CHIP-K30A proteins that both contain functional U boxes (Fig. 3E), confirming that the T246M mutation abolishes CHIP's ubiquitin ligase activity. Taken together, these data suggest that the CHIP-T246M mutation is, at minimum, a partial loss-of-function mutation, which results in an inability of the mutant protein to polyubiquitinate both chaperone-bound proteins and the chaperone proteins themselves, functions that are integral to CHIP's role in protein quality control (26, 28).

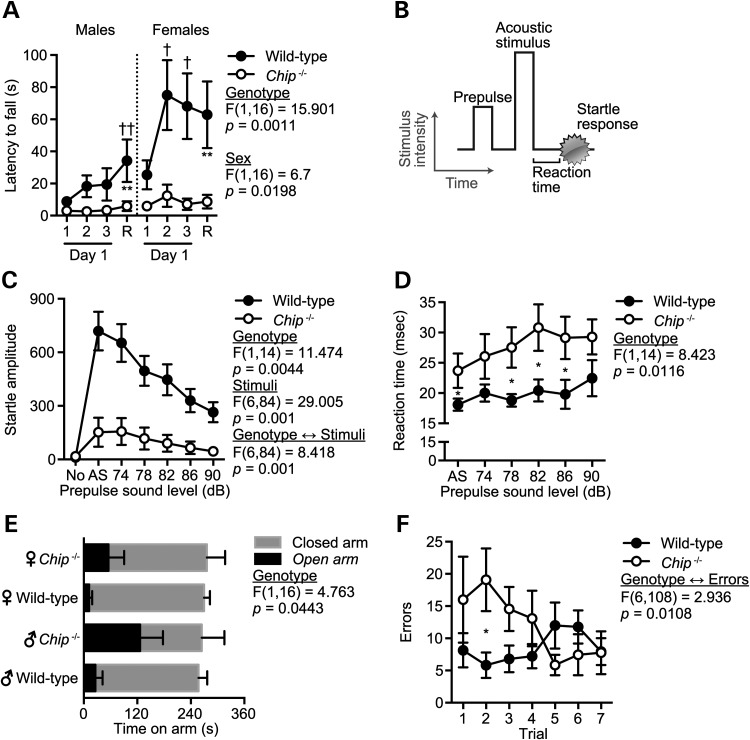

CHIP-deficient mice exhibit defects in motoric, sensory, cognitive and reproductive function

The profound cerebellar ataxia exhibited by both siblings homozygous for the CHIP-T246M substitution suggests that CHIP plays a critical role in maintaining cerebellar function. Given the autosomal recessive nature of CHIP deficiency in our GHS subjects, we first wanted to assess the neurological behavior of Chip–/− mice to determine if the loss of CHIP expression leads to impairments associated with cerebellar ataxia. Our group has previously described a line of mice deficient in CHIP expression (29, 30). Given the data above linking the human CHIP-T246M mutation with cognitive impairments, we evaluated the phenotype of Chip−/− mice using a battery of behavioral assessments (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1A). The rotarod test is extensively used in mouse models to detect cerebellar dysfunction by testing motor coordination and motor learning on a rotating dowel. The performance of Chip−/− mice on the rotarod demonstrated a severe motoric impairment irrespective of gender, with wild-type mice having between 2.9 ± 0.6- and 4.2 ± 1.8-fold increase in latency to falling times in male and female mice, respectively, compared with Chip−/− mice (Fig. 4A). The performance of Chip−/− mice did not improve with retesting (Fig. 4A), demonstrating a lack of motor learning. To further confirm a motoric defect and to test for defects in sensory gating, we measured the acoustic startle response in wild-type and Chip−/− mice (Fig. 4B). Consistent with the motoric impairment observed in Chip−/− mice using the rotarod assessment, the magnitude of the startle response was reduced 86% in Chip−/− mice compared to wild-type mice (Fig. 4C). Additionally, the reaction time to the acoustic startle was delayed across all sound levels by an average of 40% ± 4% (7.8 ms) in Chip−/− mice (Fig. 4D), consistent with our hypothesis that the loss of CHIP expression results in motoric impairment due to cerebellar dysfunction. Interestingly, prepulse inhibition levels were not affected by the loss in CHIP expression (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1B), suggesting that sensory gating (as well as auditory function) was not impaired. In addition to the deficits attributed to cerebellar dysfunction, Chip−/− mice also exhibited an aberrant pattern of exploration in a novel environment demonstrated by increased time in the open arms of the elevated plus maze (EPM; Fig. 4E) and a higher error rate in the acquisition of a spatial learning task in the Barnes maze (Fig. 4F) compared with wild-type mice, suggesting that hippocampal function may also be impaired with the loss of CHIP function. Additional testing found no differences in physical activity, both in the EPM and open field (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1C–E), latency measurers in a spatial task (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1F) or in social behavior (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1F). In gait testing, Chip−/− mice took smaller steps relative to wild-type mice (8–16% reduction in stride length, F(1,16) = 5.515, P = 0.032); however, there were no differences in overlap, front paw stride length or front paw and hind paw base width (data not shown), suggesting that motoric synchrony is not altered. Taken together, the loss of CHIP expression appears to have a selective impact in motoric, sensory and cognitive function, in particular with tasks attributed to cerebellar function.

Figure 4.

Chip−/− mice have extreme ataxia and other selective motoric and cognitive impairments. (A) Latency to fall from an accelerating rotarod represented by the mean ± SEM for either Chip−/− or wild-type mice (n = 5 per genotype per gender). The first three trials were given on the first day of rotarod testing. Retest (R) indicates the highest latency across two trials given 48 h after the day one trials: **P < 0.01 comparing Chip−/− versus wild-type mice at the retest; †P < 0.05 and ††P < 0.01 comparing the indicated time point with first trial within the genotype. (B) The acoustic startle response comprises a prepulse followed by an acoustic stimulus (AS, 120 dB). Both the reaction time to the AS and the magnitude of the response were measured. (C and D) Amplitude and reaction time of the startle response following AS are represented by the mean ± SEM for each genotype (n = 6 and 10 for Chip−/− and wild-type mice, respectively). Trials included no stimulus trials (No) and AS alone trials: P < 0.05 comparing Chip−/− versus wild-type mice across all stimulus conditions shown in (C) or as indicated by * in (D). (E and F) Time on the open and closed arms of an EPM (E) and the number of errors (incorrect holes explored) before finding the target hole on the Barnes maze (F) represented by the mean ± SEM for each genotype (n = 10): *P < 0.05 comparing Chip−/− versus wild-type mice.

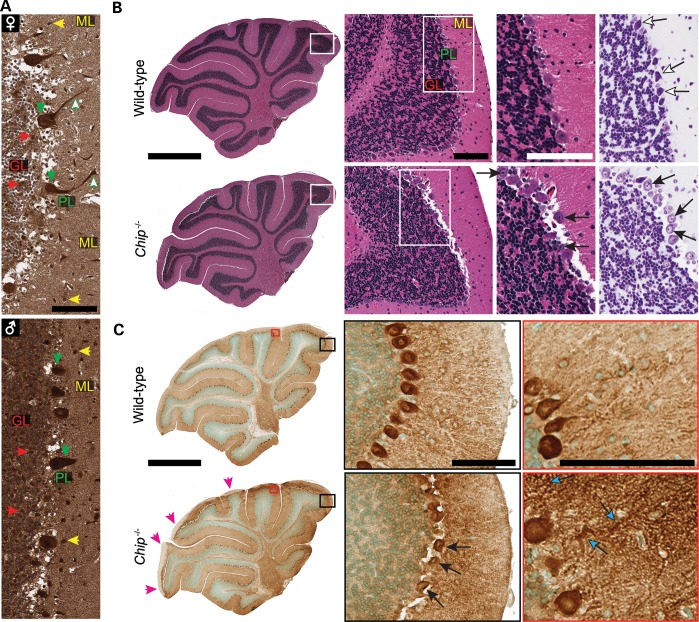

CHIP expression in the human cerebellum and the neuropathological and reproductive phenotype of Chip−/− mice

In the healthy human brain, CHIP is widely expressed throughout, including the molecular and granular region of the cerebellum where it is abundantly expressed in Purkinje cells (Fig. 5A). A similar pattern of CHIP immunoreactivity is found in mouse brains (31). Histological examination of sagittal cerebellar sections from Chip−/− mice revealed cellular loss throughout the various lobes of the cerebellum, specifically in the Purkinje cell layer with noticeable degeneration and a 3-fold increase in the number of pyknotic nuclei compared with an intact Purkinje cell layer in wild-type cerebellum (Fig. 5B and Supplementary Material, Fig. S3A), mimicking the observation of Purkinje cell loss identified in the neuropathological analysis in a deceased GHS patient with disordered ubiquitination (RNF216 and OTUD4 mutations) (2). The effect on Purkinje cell pathology was confirmed with the Purkinje cell-specific marker, calbindin (Fig. 5C, middle). Additionally, calbindin staining revealed a mosaic expression pattern in Chip−/− mice where calbindin expression in the molecular layer is reduced or absent in regions with significant Purkinje cell loss (Fig. 3C, left) similar to other mouse models of cerebellar ataxia (32). Likewise, the cerebellar regions of Chip−/− mice that do contain intact Purkinje cells exhibited severe dendritic swelling (Fig. 3C, right), a common feature in ataxias (33, 34). Taken together, these data demonstrate that the complete loss of CHIP function in our mouse model results in behavioral and cellular phenotypes consistent with the cerebellar ataxia found in human subjects with the T246M mutation.

Figure 5.

CHIP expression in human cerebellum and the loss of Purkinje cells in Chip−/− mice. (A) Immunohistochemistry of CHIP expression in adult human cerebellum from a healthy female (♀) and male (♂) with the major regions of the cerebellum identified: molecular layer (ML), Purkinje cell layer (PL) and the granular layer (GL). The colored arrows highlight intense CHIP immunoreactivity throughout the cerebellum including increased reactivity in Purkinje cells, both in the cell body (downward arrows) and dendrites (upward arrows). Scale bar represents 100 μm. (B) Representative whole cerebellar sagittal sections from wild-type and Chip−/− cerebellums (left) with the major regions labeled at higher power (middle) as shown in (A) stained with either hematoxylin and eosin (left, middle) or cresyl violet (right). The open arrows identify normal Purkinje cells in wild-type mice, whereas the closed arrows identify the pyknotic nuclei in Purkinje cells in Chip−/− cerebellums. (C) Representative whole cerebellar sagittal sections from wild-type and Chip−/− cerebellums immunostained for calbindin (left). Magenta arrowheads (left) indicate regions with no calbindin immunoreactivity and the black and red boxes correspond to the higher power images (middle and right, respectively). The closed arrows identify the pyknotic nuclei present in Purkinje cells (middle) and the cyan arrows identify swollen dendrites in Chip−/− cerebellums. (B and C) Scale bars for whole cerebellum and higher power images are 1 mm and 100μm, respectively.

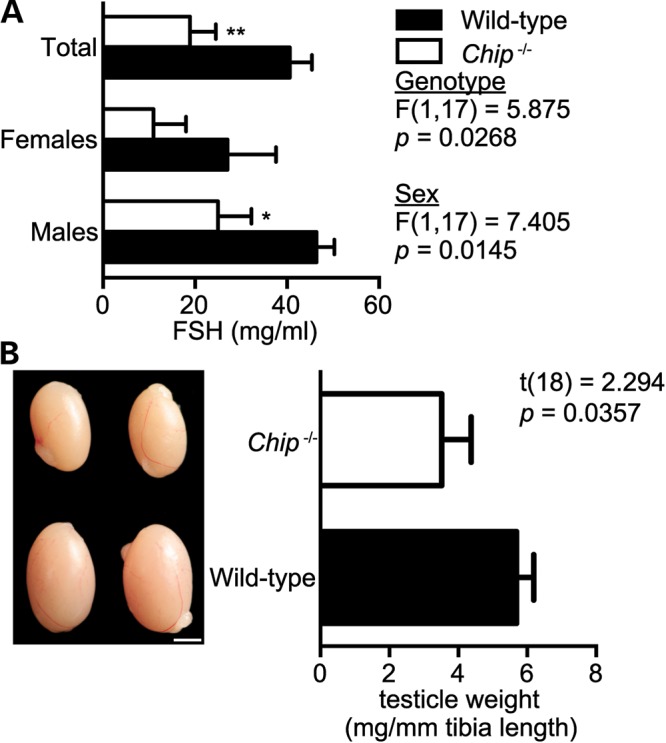

The profound lack of sexual development in patients II-1 and II-2 suggests that CHIP plays a role in neuroendocrine signaling and is necessary for proper sexual development. Notably, since originally deriving the Chip−/− mice (29), we have long been aware of the inability of Chip−/− breeding pairs to successfully mate, necessitating that the Chip−/− colony be maintained through Chip+/− crossings. Not surprisingly, FSH levels in Chip−/− mice were reduced >50% when compared with wild-type littermate mice, irrespective of gender (Fig. 6A), consistent with the low levels of FSH in patients II-1 and II-2 (Table 1). As an additional measure of gonadal dysfunction in Chip−/− mice, we measured testicular weight and observed a 38% decrease in Chip−/− testes compared with wild-type testes (Fig. 6B). Not surprisingly, CHIP is expressed in wild-type mouse testes as well as in both male and female human gonads (Supplementary Material, Fig. S3B and C). Therefore, the Chip−/− mice also appear to encompass some of the neuroendocrine deficiencies seen in patients II-1 and II-2 with the CHIP T246M mutation. In summary, given the likeness of the neurological and neuroendocrine phenotypes in the Chip−/− mice with those reported in the GHS patients described in this study, it is highly probably that the c.737C→T in the STUB1 gene results in a loss of CHIP function in these patients and directly contributes to the disease phenotype observed in this pedigree.

Figure 6.

Hypogonadism in Chip−/− mice. (A) Serum levels of FSH in wild-type and Chip−/− mice represented by the mean ± SEM for each genotype (n = 10): *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 comparing Chip−/− versus wild-type mice. (B) Representative pictographs of testes and testicle weights from wild-type and Chip−/− mice. Scale bar represents 20 mm. Weights are represented in mg of testicle per mm of tibia length to control for animal size and represented by the mean ± SEM for each genotype (n = 10 and 8, wild-type and Chip−/− mice, respectively).

DISCUSSION

There is considerable heterogeneity in terms of age of onset and progression of symptoms within groups of clinical syndromes presenting with both ataxia and hypogonadism (35). Previous studies have found mutations in POLR3A and GBA2 associated with both ataxia and hypogonadism (36, 37), but given the additional complex clinical features in these patients, they were not diagnosed with GHS. More recently, disordered ubiquitination was proposed as a contributing factor to the etiology of GHS, demonstrated by the identification of mutations in the E3 ligase RNF216 and deubiquitinase OTUD4 associated with GHS in non-Asian populations (2). Consistent with an integral role for ubiquitination in GHS pathophysiology, in this study, we identified a mutation in the STUB1 gene encoding the E3 ligase CHIP (Fig. 2A and C) that results in a GHS phenotype (Fig. 1A and B). Although both hypo- and hypergonadotropic forms of GHS have been reported, most GHS patients, including the RNF216-associated GHS patients, usually present with hypogonadotropic-induced hypogonadism (2, 11). In our patients, the level of gonadotropin is low given their age, but is in the normal range for prepubescent individuals; this may indicate a more mild abnormality in the reproductive–endocrine axis, although the lack of sexual development remains remarkable. Outside of the fundamental phenotype of GHS, ataxia and hypogonadism, there are some other distinct differences in the clinical features of our patients to those harboring RNF216 and OTUD4 mutations; most notably, we did not observe dementia or white matter lesions described previously (2). However, as mild cognitive impairment was observed in our patients (Table 1) and likewise in Chip−/− mice (Fig. 4), we speculate that cognitive impairment may also act as a core clinical feature in the STUB1-associated GHS patients. Long-term follow-up of the patients will be needed to clarify this issue. Our finding suggests that patients presenting with GHS without RNF216 or OTUD4 mutations (2) are also negative for any mutations in the STUB1 gene and that other undiscovered genetic contributors of GHS remain to be elucidated.

It is intriguing that deficiency in either RNF213 or CHIP can both lead to a similar clinical syndrome. One possible explanation is RNF213 and CHIP ubiquitin ligase substrates converge to a shared pathway that contributes to GHS. For example, CHIP could promote ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of TRAF2, thereby inhibiting the nuclear localization and transcriptional activity of NF-κB (38). RNF216 is also an inhibitor of TNF and IL-1-induced NF-κB activation and can also act as a key negative regulator of sustained 2DL4-mediated NF-κB signaling (39, 40). Thus, dysregulation of the NF-κB pathway caused by either RNF213 or CHIP deficiencies is a potential common disease-causing factor for GHS. Alternatively, RNF213 may have some physiological functions that overlap with the functions of CHIP. Previous studies have demonstrated that the loss of CHIP expression results in increased accumulation of misfolded proteins and eventual cell death, whereas over expression of CHIP can be protective in models of chronic neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson's and Alzheimer's disease (7–9, 28, 41). Given the observed neurodegeneration including ataxia and dementia in patients harboring RNF213 mutations, loss of the E3 ligase activity of RNF213 may also be associated with protein misfolding and aggregation in neurodegenerative disorders, although more evidence is needed to support this hypothesis.

Our molecular characterization of the STUB1 c.737C→T, p.Thr246Met mutation demonstrates a loss in ubiquitin ligase activity (Fig. 3D and E), while still maintaining chaperone interactions (Fig. 3B and C). The ability of CHIP-T246M to maintain its chaperone interaction without a functional U box may result in a dominant-negative phenotype versus a complete loss of CHIP function. Generation of a CHIP-T246M knock-in mouse and comparison of the pathophysiology related to GHS phenotypes will provide valuable insight into the role of CHIP in this disease. Nonetheless, Chip−/− mice share several striking physiological similarities to GHS patients with ataxia and hypogonadism (Fig. 1), including neuronal degeneration (Fig. 5B and C), pronounced ataxic motor behavior (Fig. 4) and reproductive impairments (Fig. 6). This strong similarity between the findings in our GHS patients and those in the Chip−/− mouse model establishes an important role for CHIP in the maintenance of cerebellar function and the reproductive–endocrine axis. Taken together, our results demonstrate that deficiency of the ubiquitin ligase CHIP causes ataxia with hypogonadism and further highlight the role of aberrant ubiquitin ligase function in the pathogenesis of GHS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Exome sequencing and candidate gene validation

Targeted exon enrichment was performed with the use of the NimbleGen SeqCap EZ Human Exome Library (Roche—NimbleGen Inc.). The exon-enriched DNA libraries were subjected to paired-end sequencing with the Illumina Hiseq2000 platform (Illumina). Sequence data were mapped with SOAP2 (42) and BWA (43) onto the hg18 human genome as a reference. We generated an average of 15 Gb of sequence with 90× average coverage for each individual as single-end, 80-bp reads, calls with variant quality <20 were filtered out and 99% of the targeted bases were covered sufficiently to pass our thresholds for calling SNPs and small indels (Beijing Genomic Institute, Shenzhen, China). Furthermore, coding regions of the STUB1, RNF213 and OTUD4 gene were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for conventional direct sequencing. Purified PCR products were sequenced on an ABI 3500 Genetic Analyzer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Sanger sequencing results were analyzed by Mutation Surveyor (Softgenetics, State College, PA, USA) and reconfirmed by the same procedure.

Expression plasmids and recombinant proteins

Mammalian expression plasmids pcDNA3-myc-CHIP, pcDNA3-myc-CHIP-K30A, pcDNA3-myc-CHIP-H260Q, HA-Ubiquitin and FLAG-HSP70 were used as described previously (5, 26, 44). CHIP, CHIP-H260Q, CHIP-K30A, CHIP-T246M and HSC70 recombinant proteins were produced in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) as His-tagged fusion proteins by induction with 0.1 mm isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside overnight at 18°C followed by purification with HisTrap™ HP columns (GE Healthcare), concentrated, and stored in in 20 mm HEPES (pH 7.4) with 150 mm NaCl.

Mutagenesis

A point mutation of threonine to methionine at position 246 of CHIP was created by site-directed mutagenesis using the Q5 Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (New England Biolabs, E0554S) according to manufacturer's instructions using previously described pcDNA3-myc-CHIP template (5) and mutagenic primers 5′-CCGTGCATCATGCCCAGTGGC-3′ and 5′-CTCCCGCATCAGCTCAAAGC-3′ (BaseChanger software, New England Biolabs). The myc-CHIP-T246 expression plasmid was produced by transformation in E. coli DH5α, purified and the single-base pair substitution was verified by DNA sequencing.

In vitro ubiquitination reactions

In vitro ubiquitination reactions were carried out as previously described (5). Briefly, 0.75 μg (1 μm) of bacterially expressed HSC70 was incubated in the presence of 2.5 μm CHIP or CHIP mutants, 50 nm purified Ube1 (BostonBiochem, E305), 2.5 μm purified UbcH5c (BostonBiochem, E2–627) and 0.25 μm ubiquitin (BostonBiochem, U100H) in 50 mm Tris (pH 7.5), 600 μm DTT, 2.5 mm MgCl2-ATP (BostonBiochem, B20) in a total volume of 10 μl for 1 h at 37°C. Samples were analyzed by 4–12% Bis–Tris SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting was performed with either anti-HSC70 (Enzo, ADI-SPA-815) or anti-CHIP (Sigma, S1073) antibodies.

Cell culture and transfection

COS-7 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma) at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. Cell transfections were performed using X-tremeGENE 9 (Roche) with the indicated plasmid DNA at a 1:3 DNA to X-tremeGENE 9 ratio.

Immunoprecipitation/co-immunoprecipitation of FLAG-HSP70/CHIP from COS-7 cells

1E6 COS-7 cells were plated in normal growth media in 10 cm2 tissue culture-treated dishes and incubated overnight under normal growth conditions. Cells were then transiently transfected with pcDNA3-mycCHIP (0.5 μg), pcDNA3-mycCHIP T246M (2.5 μg), pcDNA3 (2.5 μg) and/or FLAG-HSP-70 (2 μg) and HA-Ubiquitin (1 μg) and incubated for 24 h under normal growth conditions, followed by treatment with 20 μm MG132 or DMSO for 2.5 h prior to harvest. Cells were washed in cold PBS and lysed in Cell Lytic M (Sigma) containing 1× HALT protease/phosphatase inhibitor (Pierce) and 50 μm PR619 (Lifesensors). Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 15 000g for 10 min. Total protein concentration was determined by BCA protein assay (Pierce) and 1 mg total protein clarified lysate incubated overnight at 4°C with 20 μg of either EZview™ Red ANTI-FLAG® M2 or ANTI-HA Affinity Gel (Sigma). The gel was then washed five times with Tris-buffered saline with 0.5% Nonident P-40; subsequently, proteins were eluted in reducing SDS-sample buffer and analyzed by SDS–PAGE and western blotting was performed using anti-Hsp70 (Enzo ADI-SPA-810), anti-FLAG HRP (Sigma, A8592), anti-HA HRP (Sigma, A6533) and anti-myc HRP (Sigma, A5598) antibodies.

Immunoprecipitation/co-immunoprecipitation of HSC70/CHIP from COS-7 cells

1E6 COS-7 cells were plated in normal growth media in 100 mm tissue culture-treated dishes and incubated overnight under normal growth conditions. Cells were then transiently transfected with pcDNA3-mycCHIP (1.5 μg), pcDNA3-mycCHIP T246M (4 μg) or pcDNA3 (1.5 μg) and HA-Ubiquitin and incubated for 24 h under normal growth conditions, followed by treatment with 20 μm MG132 or DMSO control for 2.5 h prior to harvest. Cells were washed 1× in cold PBS and lysed in Cell Lytic M (Sigma) containing 1× HALT protease/phosphatase inhibitor (Pierce) and 50 μm PR619 (LifeSensors). Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 15 000g for 10 min. Total protein concentration was determined by BCA protein assay (Pierce) and 1.8 mg total protein clarified lysates were incubated overnight at 4°C with 10 μg anti-Hsc70 (Enzo ADI-SPA-815) or rat IgG antibodies. One hundred and twenty microliters of Protein-G Dynabeads (Invitrogen) were then added to each sample and incubated for 0.5 h at room temperature with rotation. Beads were washed four times with phosphate-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween-20; subsequently, proteins were eluted in SDS-sample buffer and analyzed by SDS–PAGE and western blotting using anti-Hsc70 (Enzo ADI-SPA-815), anti-CHIP (abcam, Ab4448), anti-HA HRP (Sigma, A6533) and anti-myc HRP (Sigma, A5598) antibodies.

Mouse behavioral assessments

All tests and measures are detailed in the Extended Experimental Procedures provided in Supplementary Material.

Histology

Mouse brains were carefully excised, gently rinsed, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h and then placed in 70% ethanol prior to embedding into paraffin. Five micrometer sections were processed for histology, and stained with either hematoxylin and eosin or cresyl violet for routine histological examination. Unstained sections were used to detect calbindin expression using immunohistochemistry. Slides were stained per the manufacturer instructions using the calbindin D1I4Q rabbit monoclonal antibody (Cell Signaling, 13176) with citrate antigen retrieval, SignalStain® Boost Detection Reagent (Cell Signaling, 8114), and SignalStain® DAB Substate Kit (Cell Signaling, 8059). Degenerating neurons were characterized via light microscopic level by cell body shrinkage, loss of Nissl substance and a small/shrunken darkly stained (pyknotic) nucleus as described (45). Human cerebellum, testes and ovary sections were from the Human Protein Atlas tissue array (46) and were stained with anti-CHIP antibody (Sigma, C9243).

Statistical analyses

For the mouse behavioral studies and hormone levels, data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA looking for effects of genotype or sex, or when applicable, repeated measures ANOVAs. Fisher's protected least-significant difference tests were used for comparing group means only when a significant F-value was determined. For all other analyses, unpaired data sets were analyzed using a two-tailed Student's t-test with P-values of <0.05 considered significant.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

FUNDING

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China grant 81070920 (to Y.X.) and the National Institutes of Health grant R01-GM061728 and Fondation Leducq (to C.P.).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are very grateful to all participating patients and their relatives. We thank Richard Quinton for discussing the related phenotype of GHS. We also thank Pamela Lockyer and Zhongjing Wang for outstanding technical support.

Conflict of Interest statement. None declared.

References

- 1.Holmes G. A form of familial degeneration of the cerebellum. Brain. 1908;30:466–489. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Margolin D.H., Kousi M., Chan Y.M., Lim E.T., Schmahmann J.D., Hadjivassiliou M., Hall J.E., Adam I., Dwyer A., Plummer L., et al. Ataxia, dementia, and hypogonadotropism caused by disordered ubiquitination. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;368:1992–2003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ballinger C.A., Connell P., Wu Y., Hu Z., Thompson L.J., Yin L.Y., Patterson C. Identification of CHIP, a novel tetratricopeptide repeat-containing protein that interacts with heat shock proteins and negatively regulates chaperone functions. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:4535–4545. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.6.4535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Connell P., Ballinger C.A., Jiang J., Wu Y., Thompson L.J., Hohfeld J., Patterson C. The co-chaperone CHIP regulates protein triage decisions mediated by heat-shock proteins. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;3:93–96. doi: 10.1038/35050618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiang J., Ballinger C.A., Wu Y., Dai Q., Cyr D.M., Hohfeld J., Patterson C. CHIP is a U-box-dependent E3 ubiquitin ligase: identification of Hsc70 as a target for ubiquitylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:42938–42944. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101968200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schisler J.C., Rubel C.E., Zhang C., Lockyer P., Cyr D.M., Patterson C. CHIP protects against cardiac pressure overload through regulation of AMPK. J. Clin. Invest. 2013;123:3588–3599. doi: 10.1172/JCI69080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Ramahi I., Lam Y.C., Chen H.K., de Gouyon B., Zhang M., Perez A.M., Branco J., de Haro M., Patterson C., Zoghbi H.Y., et al. CHIP protects from the neurotoxicity of expanded and wild-type ataxin-1 and promotes their ubiquitination and degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:26714–26724. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601603200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petrucelli L., Dickson D., Kehoe K., Taylor J., Snyder H., Grover A., De Lucia M., McGowan E., Lewis J., Prihar G., et al. CHIP and Hsp70 regulate tau ubiquitination, degradation and aggregation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2004;13:703–714. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tetzlaff J.E., Putcha P., Outeiro T.F., Ivanov A., Berezovska O., Hyman B.T., McLean P.J. CHIP targets toxic alpha-Synuclein oligomers for degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:17962–17968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802283200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lessig S., Nie D., Xu R., Corey-Bloom J. Changes on brief cognitive instruments over time in Parkinson's disease. Mov. Disord. 2012;27:1125–1128. doi: 10.1002/mds.25070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seminara S.B., Acierno J.S., Jr., Abdulwahid N.A., Crowley W.F., Jr., Margolin D.H. Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and cerebellar ataxia: detailed phenotypic characterization of a large, extended kindred. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002;87:1607–1612. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.4.8384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sherry S.T., Ward M.H., Kholodov M., Baker J., Phan L., Smigielski E.M., Sirotkin K. dbSNP: the NCBI database of genetic variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:308–311. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Genomes Project C., Abecasis G.R., Altshuler D., Auton A., Brooks L.D., Durbin R.M., Gibbs R.A., Hurles M.E., McVean G.A. A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature. 2010;467:1061–1073. doi: 10.1038/nature09534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.International HapMap C., Frazer K.A., Ballinger D.G., Cox D.R., Hinds D.A., Stuve L.L., Gibbs R.A., Belmont J.W., Boudreau A., Hardenbol P., et al. A second generation human haplotype map of over 3.1 million SNPs. Nature. 2007;449:851–861. doi: 10.1038/nature06258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.International HapMap C. A haplotype map of the human genome. Nature. 2005;437:1299–1320. doi: 10.1038/nature04226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li G., Ma L., Song C., Yang Z., Wang X., Huang H., Li Y., Li R., Zhang X., Yang H., et al. The YH database: the first Asian diploid genome database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D1025–1028. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tennessen J.A., Bigham A.W., O'Connor T.D., Fu W., Kenny E.E., Gravel S., McGee S., Do R., Liu X., Jun G., et al. Evolution and functional impact of rare coding variation from deep sequencing of human exomes. Science. 2012;337:64–69. doi: 10.1126/science.1219240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krawitz P.M., Schweiger M.R., Rodelsperger C., Marcelis C., Kolsch U., Meisel C., Stephani F., Kinoshita T., Murakami Y., Bauer S., et al. Identity-by-descent filtering of exome sequence data identifies PIGV mutations in hyperphosphatasia mental retardation syndrome. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:827–829. doi: 10.1038/ng.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodelsperger C., Krawitz P., Bauer S., Hecht J., Bigham A.W., Bamshad M., de Condor B.J., Schweiger M.R., Robinson P.N. Identity-by-descent filtering of exome sequence data for disease-gene identification in autosomal recessive disorders. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:829–836. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adzhubei I.A., Schmidt S., Peshkin L., Ramensky V.E., Gerasimova A., Bork P., Kondrashov A.S., Sunyaev S.R. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar P., Henikoff S., Ng P.C. Predicting the effects of coding non-synonymous variants on protein function using the SIFT algorithm. Nat. Protocols. 2009;4:1073–1081. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sailer A., Houlden H. Recent advances in the genetics of cerebellar ataxias. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2012;12:227–236. doi: 10.1007/s11910-012-0267-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sathirapongsasuti J.F., Lee H., Horst B.A., Brunner G., Cochran A.J., Binder S., Quackenbush J., Nelson S.F. Exome sequencing-based copy-number variation and loss of heterozygosity detection: exomeCNV. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2648–2654. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang M., Windheim M., Roe S.M., Peggie M., Cohen P., Prodromou C., Pearl L.H. Chaperoned ubiquitylation–crystal structures of the CHIP U box E3 ubiquitin ligase and a CHIP-Ubc13-Uev1a complex. Mol. Cell. 2005;20:525–538. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meacham G.C., Patterson C., Zhang W., Younger J.M., Cyr D.M. The Hsc70 co-chaperone CHIP targets immature CFTR for proteasomal degradation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;3:100–105. doi: 10.1038/35050509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qian S.B., McDonough H., Boellmann F., Cyr D.M., Patterson C. CHIP-mediated stress recovery by sequential ubiquitination of substrates and Hsp70. Nature. 2006;440:551–555. doi: 10.1038/nature04600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qian S.B., Waldron L., Choudhary N., Klevit R.E., Chazin W.J., Patterson C. Engineering a ubiquitin ligase reveals conformational flexibility required for ubiquitin transfer. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:26797–26802. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.032334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar P., Pradhan K., Karunya R., Ambasta R.K., Querfurth H.W. Cross-functional E3 ligases Parkin and C-terminus Hsp70-interacting protein in neurodegenerative disorders. J. Neurochem. 2012;120:350–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dai Q., Zhang C., Wu Y., McDonough H., Whaley R.A., Godfrey V., Li H.H., Madamanchi N., Xu W., Neckers L., et al. CHIP activates HSF1 and confers protection against apoptosis and cellular stress. EMBO J. 2003;22:5446–5458. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Min J.N., Whaley R.A., Sharpless N.E., Lockyer P., Portbury A.L., Patterson C. CHIP deficiency decreases longevity, with accelerated aging phenotypes accompanied by altered protein quality control. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2008;28:4018–4025. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00296-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anderson L.G., Meeker R.B., Poulton W.E., Huang D.Y. Brain distribution of carboxy terminus of Hsc70-interacting protein (CHIP) and its nuclear translocation in cultured cortical neurons following heat stress or oxygen-glucose deprivation. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2010;15:487–495. doi: 10.1007/s12192-009-0162-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Becker E.B., Oliver P.L., Glitsch M.D., Banks G.T., Achilli F., Hardy A., Nolan P.M., Fisher E.M., Davies K.E. A point mutation in TRPC3 causes abnormal Purkinje cell development and cerebellar ataxia in moonwalker mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:6706–6711. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810599106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sleat D.E., Wiseman J.A., El-Banna M., Price S.M., Verot L., Shen M.M., Tint G.S., Vanier M.T., Walkley S.U., Lobel P. Genetic evidence for nonredundant functional cooperativity between NPC1 and NPC2 in lipid transport. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:5886–5891. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308456101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang Q., Hashizume Y., Yoshida M., Wang Y., Goto Y., Mitsuma N., Ishikawa K., Mizusawa H. Morphological Purkinje cell changes in spinocerebellar ataxia type 6. Acta Neuropathol. 2000;100:371–376. doi: 10.1007/s004010000201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alsemari A. Hypogonadism and neurological diseases. Neurol. Sci. 2013;34:629–638. doi: 10.1007/s10072-012-1278-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bernard G., Chouery E., Putorti M.L., Tetreault M., Takanohashi A., Carosso G., Clement I., Boespflug-Tanguy O., Rodriguez D., Delague V., et al. Mutations of POLR3A encoding a catalytic subunit of RNA polymerase Pol III cause a recessive hypomyelinating leukodystrophy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011;89:415–423. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martin E., Schule R., Smets K., Rastetter A., Boukhris A., Loureiro J.L., Gonzalez M.A., Mundwiller E., Deconinck T., Wessner M., et al. Loss of function of glucocerebrosidase GBA2 is responsible for motor neuron defects in hereditary spastic paraplegia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2013;92:238–244. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jang K.W., Lee K.H., Kim S.H., Jin T., Choi E.Y., Jeon H.J., Kim E., Han Y.S., Chung J.H. Ubiquitin ligase CHIP induces TRAF2 proteasomal degradation and NF-kappaB inactivation to regulate breast cancer cell invasion. J. Cell. Biochem. 2011;112:3612–3620. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen D., Li X., Zhai Z., Shu H.B. A novel zinc finger protein interacts with receptor-interacting protein (RIP) and inhibits tumor necrosis factor (TNF)- and IL1-induced NF-kappa B activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:15985–15991. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108675200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miah S.M., Purdy A.K., Rodin N.B., MacFarlane A.W.t., Oshinsky J., Alvarez-Arias D.A., Campbell K.S. Ubiquitylation of an internalized killer cell Ig-like receptor by Triad3A disrupts sustained NF-kappaB signaling. J. Immunol. 2011;186:2959–2969. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Williams A.J., Knutson T.M., Colomer Gould V.F., Paulson H.L. In vivo suppression of polyglutamine neurotoxicity by C-terminus of Hsp70-interacting protein (CHIP) supports an aggregation model of pathogenesis. Neurobiol. Dis. 2009;33:342–353. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li R., Yu C., Li Y., Lam T.W., Yiu S.M., Kristiansen K., Wang J. SOAP2: an improved ultrafast tool for short read alignment. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1966–1967. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li H., Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosser M.F., Washburn E., Muchowski P.J., Patterson C., Cyr D.M. Chaperone functions of the E3 ubiquitin ligase CHIP. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:22267–22277. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700513200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garman R.H. Histology of the central nervous system. Toxicol. Pathol. 2011;39:22–35. doi: 10.1177/0192623310389621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Uhlen M., Oksvold P., Fagerberg L., Lundberg E., Jonasson K., Forsberg M., Zwahlen M., Kampf C., Wester K., Hober S., et al. Towards a knowledge-based Human Protein Atlas. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:1248–1250. doi: 10.1038/nbt1210-1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.