Abstract

We evaluated the performance of LOINC® and RadLex standard terminologies for covering CT test names from three sites in a health information exchange (HIE) with the eventual goal of building an HIE-based clinical decision support system to alert providers of prior duplicate CTs. Given the goal, the most important parameter to assess was coverage for high frequency exams that were most likely to be repeated. We showed that both LOINC® and RadLex provided sufficient coverage for our use case through calculations of (a) high coverage of 90% and 94%, respectively for the subset of CTs accounting for 99% of exams performed and (b) high concept token coverage (total percentage of exams performed that map to terminologies) of 92% and 95%, respectively. With trends toward greater interoperability, this work may provide a framework for those wishing to map radiology site codes to a standard nomenclature for purposes of tracking resource utilization.

Introduction

Mapping is the process where terms, codes, concepts, descriptors or expressions are linked or translated to entities in another terminology1. A common reason for mapping procedure test names to a standardized terminology is to facilitate exchange of health care information among different health care providers caring for the same patient or group of patients2,3. This is especially pertinent in the setting of a health information exchange (HIE) organization where the primary purpose is to share patient health information securely among participating health care institutions to enhance patient care. Other potential secondary uses for mapping in the setting of an HIE include: facilitating exchange of data for use in clinical decision support programs, including alert/notification systems4 and evidence based guidelines; pooling of data for use in outcomes analysis and clinical research2; and for use in public health (e.g., syndromic surveillance and population level quality monitoring)5.

For our project, we sought to map computed tomography (CT) test names from participating HIE hospitals to a standard nomenclature as pre-requisite work for the development of a clinical decision support system (CDSS) that will alert providers at the point of order entry to the presence of prior similar CT exams, regardless of where within an HIE that previous examination had been performed. Its primary purpose will be to reduce the number of exams that might be repeated simply because a prior study was not immediately available, and to reduce the amount of cumulative radiation delivered to some patients. This mapping will allow the alerting system to recognize different names and codes across sites as the same type of exam. For example, it would recognize that a “CT BRAIN” performed at one institution is equivalent to a “CT HEAD” performed at another.

This paper describes our experience mapping distinct CT test names from three participating HIE sites to the Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC®) terminology, RadLex terminology, and a combination of these two. In addition, we assess how comprehensive these terminologies are, and whether they are sufficient for our needs as they currently exist.

Background and Significance

From a “content dependent” perspective, in which terminologies are evaluated for their performance within a particular domain, this paper uses the concepts of 1) Concept Type Coverage which refers to the percentage of unique test names (types) from a site that map to a standard nomenclature, and 2) Concept Token Coverage which refers to the percentage of actual exams performed (tokens) that map to a standardized terminology6,7. For example, if 85 of 100 exam names at an institution map to LOINC terms, the concept type coverage would be 85%. Similarly, if 95,000 of an institution’s 100,000 annual exams performed map to LOINC terms, the concept token coverage would be 95%. The distinction between these concepts is important, because even though an institution may have low concept type coverage (e.g., only 40–50% of its exam codes map to LOINC), it may still possess a high concept token coverage (>90% of exams performed at that institution map to LOINC), indicating that a small percentage of codes account for the majority of exams performed.

Previous studies have used concept type and concept token coverage to evaluate LOINC’s coverage of laboratory codes6,8. Two papers reported LOINC’s coverage of radiology codes in local health systems9,10. One study looked at LOINC’s coverage of labs and radiology codes across an HIE11. However, we are unaware of any previous studies that have compared LOINC to RadLex for coverage of radiology codes at individual sites or across an HIE.

Materials and Methods

Data Sources

All analyses for the mapping study were performed using de-identified data from NYCLIX (The New York Clinical Information Exchange) an HIE that covered much of Manhattan.* CT exam names and frequencies were obtained through NYCLIX for three NYCLIX sites from March 1, 2009 to July 24, 2012.

Standard Terminologies

The exam names from each site were mapped to the LOINC and RadLex terminology standards. LOINC was developed by the Regenstrief Institute to encode laboratory tests and clinical observations2,3,12 including radiology procedure codes, and contained 738 unique CT codes at the time of this study (August 2012)3,12. RadLex was developed by the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA) and includes the RadLex Playbook, a component that is intended to provide a standard, comprehensive lexicon of radiology orderables and procedure step names, the most recent version of which (version 1.0, released on November 1, 2011) contains 342 unique CT exam names and codes13. Other types of radiology codes besides CT (e.g., MRI, PET, ultrasound) have not yet been added to RadLex.

Mapping

The first author, who is a radiologist with domain expertise, performed mapping by inspection of CT test names, descriptions, and codes from local sites looking for the presence of an exact one-to-one correspondence between the site exam code and the LOINC or RadLex exam code. Mapping local CT exam names to LOINC codes and names were done with the assistance of the Regenstrief LOINC Mapping Assistant (RELMA) through use of its term-by-term search browser function 2,14 and supplemented by manual review of the LOINC code and description database, both downloaded from the LOINC website12. RELMA’s term-by-term search browser allows the user to enter the local CT test name into a search field retrieving a list of potential matching LOINC codes15. For example, the exam name “CT Head wo contrast” when entered into RELMA returned 11 search terms, including: “Head CT W and WO contrast IV,” “Skull base CT WO contrast,” and “Head CT WO contrast.” “Head CT WO contrast “ was chosen based on the reviewer’s clinical domain expertise. Mapping local CT exam names to RadLex names and codes was done through manual inspection of RadLex Playbook, downloaded as a CSV file from the RSNA website13. For example, when “CT Head wo contrast” was looked up in the RadLex Playbook, the reviewer first sorted the file alphabetically then scanned the exam names for the closest match, allowing “CT HEAD WO IVCON” to be chosen. Mapping data for each of the three sites were entered into Microsoft Access®.

CT exams were categorized as: 1) mapped to LOINC; 2) mapped to RadLex; 3) mapped to a combination of LOINC and RadLex; or 4) not able to be mapped to either. We defined exams that mapped to a combination of LOINC and RadLex as consisting of exams that could be mapped to either or both of these terminologies. We sought to map local CT test names and codes to corresponding LOINC and RadLex names/codes with the same level of granularity. However, cases in which there was no LOINC or RadLex code of matching granularity were mapped to less granular standard terminology codes that encompassed the more specific local codes if possible. For example, Site 2 exam descriptions of “CT guided biopsy of the left kidney” and “CT guided biopsy of the right kidney” have no corresponding LOINC or RadLex codes that specify laterality. These exams were both mapped to the less granular “CT guided biopsy of the kidney” exam name/code contained in both the LOINC and RadLex nomenclatures. In cases where a combination exam code (e.g., CT Neck/Chest) did not have a single corresponding LOINC or RadLex code, we initially determined this to be a non-match for our analysis since there was not a one-to-one correspondence. We then repeated the analysis mapping combination exam codes from the sites to multiple LOINC or RadLex codes wherever possible (e.g., CT Neck/Chest is mapped to CT neck and CT Chest as separate codes) to see how performance was improved.

De-duplication of Codes

For the purposes of this study, we defined duplicate codes as those that have the exact same LOINC and/or RadLex mapping profile. We de-duplicated within sites and across sites. Duplicate codes typically consisted of codes for the exact same type of exam that differ either in (a) a prefix or suffix, which in most cases specify either the machine location or sub-site location, or (b) slight string variations in the name. For example, Site 1’s “RA CT ABDOMEN WITH CONTRAST” and Site 3’s “AECT ABDOMINAL WITH CONTRAST” are duplicate codes that differ both in prefixes specifying a machine location and in slight string variations in the name; these exams both map to LOINC code 30599-5 (Abdomen CT W contrast) and RadLex code RPID5 (RAD ORDER CT ABD W IVCON). Code de-duplication was also performed by first mapping all local site codes to the standard terminologies and then reviewing the codes to find those that mapped to the same LOINC and RadLex codes. At both the individual and combined sites, duplicate codes were combined into a single unique code, and the extra code(s) were excluded from our analysis. The exam frequency of each extra duplicate code was added to the exam frequency of the unique code to accurately reflect the total frequency of each exam type performed.

Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed to assess the comprehensiveness of the LOINC, RadLex, and combined LOINC/RadLex terminology standards for mapping CT terms. Concept type coverages were calculated as the percentage of local CT codes that could be mapped to LOINC, RadLex, and a combination of LOINC and RadLex for each site as well for total combined sites. Concept token coverages were directly calculated for the LOINC, RadLex, and combined LOINC/RadLex standard terminologies by dividing the number of exams actually performed that could be mapped to these terminologies respectively by the total number of exams performed. This was also done for the individual sites and for the combined sites.

We then calculated the number of unique exam codes/concept types for the sites combined that account for the top 80%, 90%, 95%, and 99% of the total exams performed, and determined the number and percentage of those studies that could be mapped to LOINC, RadLex, or a combination of LOINC and RadLex. Our rationale for this step was to emphasize a real-world application of this process. Specifically, even if the terminology standards could not map all local exam codes, it might help to determine or predict if the standard terminologies were sufficient enough to map a high percentage of the exams performed. This may be sufficient in practice, since this would account for most of the studies that might be repeated across institutions. Within these subsets of codes, we also qualitatively studied those exams that could not be directly mapped to a terminology standard to determine what prevented these particular exams from being mapped.

The Mount Sinai Institutional Review Board reviewed this study protocol and determined that it is “not human research”, and is therefore exempt from formal Board review.

Results

The number of unique exam descriptions/codes from each of the three sites and the sites combined were 292, 131, 557, and 980 respectively. Following code de-duplication, these were reduced to 135, 100, 132, and 217 codes respectively.

Concept type coverage for the RadLex, LOINC and the combination of RadLex/LOINC terminology standards for sites combined were 75%, 70% and 84% respectively. At the individual sites, concept type coverage for the LOINC, RadLex, and combined LOINC/RadLex terminologies ranged from 72–84%, 75–82% and 87–89% respectively (Table 1). Unique test names that could not map to either terminology fell into several categories, including combination exams (e.g., “CT Neck/Chest” and “Whole body PET/CT”), highly specialized exams (e.g., site 3’s “CT guided cyst aspiration right ilium”), CT names set to match corresponding CPT codes (e.g. site 2’s “CT Orbit, Sella, Posterior Fossa, or Temporal Bones without contrast” set to match CPT code of 70480), and CT exams that specify a lower level of granularity than the terminology standard (e.g., site 3’s “CT of the lower extremity with contrast” cannot be mapped to RadLex as the terminology requires specification of right, left, or bilateral).

Table 1.

Concept type coverage (the percentage of unique test names (types) from a site that map to a standard nomenclature) by LOINC, RadLex, and combination of LOINC/RadLex terminologies

| Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 3 | Combined Sites | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (Percent) of codes that map to LOINC (LOINC Concept Type Coverage) | 108 (80%) | 84(84%) | 95 (72%) | 151(70%) |

| Number (Percent) of codes that map to RadLex (RadLex Concept Type Coverage) | 112 (82%) | 82(82%) | 99 (75%) | 162 (75%) |

| Number (Percent) of codes mapping to combination LOINC/RadLex (Combination LOINC/RadLex Concept Type Coverage) | 120 (89%) | 87(87%) | 115 (87%) | 183 (84%) |

Concept token coverage for the LOINC, RadLex and the combination of RadLex/LOINC terminology standards for sites combined were 92%, 95% and 96% respectively. At the individual sites, concept token coverage for the LOINC, RadLex, and combined LOINC/RadLex terminologies ranged from 88–98%, 92–98% and 94–99% respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Concept token coverage (the percentage of actual exams performed (tokens) that map to a standardized terminology) for LOINC, RadLex, and combined LOINC/RadLex terminologies.

| Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 3 | Combined Sites | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOINC Concept token coverage | 88% | 98% | 93% | 92% |

| RadLex Concept token coverage | 98% | 92% | 94% | 95% |

| Combined LOINC-RadLex Concept token coverage | 99% | 98% | 94% | 96% |

When combination exams were alternatively mapped to multiple LOINC or RadLex codes, the concept type coverage for LOINC across sites ranged from 86–96% and was 90% for all sites combined, the coverage for RadLex ranged from 82–94% and was 86% for all sites combined, and the coverage for LOINC and RadLex combined ranged from 91–99% and was 94% for all sites combined. The concept token coverage for LOINC and the combined LOINC/RadLex terminologies was 99% across sites as well as for all sites combined. The concept token coverage for RadLex ranged from 95–99% for the individual sites and was 99% for all sites combined.

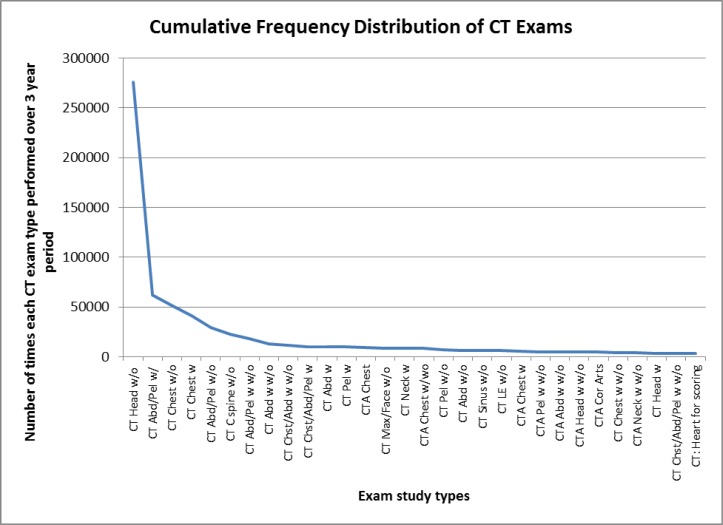

Analysis of LOINC and RadLex coverage of unique exam codes/concept types that account for the top 80%, 90%, 95%, and 99% of the exams performed across the sites combined is displayed in Table 3. There was a highly skewed distribution of exams, with a relatively small number of the most frequently performed exam types accounting for a large percentage of the total exams performed/exam volume across the sites combined (Figure 1). As an illustration, CT of the head without contrast with 276,166 exams performed over a 3 year period accounts for approximately 25% of all exams performed and the 10 most frequently ordered exams account for 72% of total exam volume. Of the 217 unique exams/concept types across the sites combined, the most frequently performed 18, 30, 46, and 89 exam types accounted for 80%, 90%, 95% and 99% of the total exam volume, respectively. All 18 (100%) of the exam types that account for 80% of the total exam volume and 29 of 30 (97%) exam types that account for 90% of the total exam volume could be mapped to both LOINC and RadLex. In the subset of exams that account for 95% of the total exam volume, 42 of 46 (91%) could be mapped to LOINC and 44 of 46 (96%) could be mapped to RadLex as well as the combined LOINC/RadLex terminologies. In the subset of exams that account for 99% of the total exam volume, 80 of 89 (90%) could be mapped to LOINC and 84 of 89 (94%) could be mapped to RadLex as well as the combined LOINC/RadLex terminologies. The only exam of the “90%” subset that could not be mapped to both terminologies was “CT Chest/Abdomen/Pelvis with IV contrast,” which is a combination exam that could not be mapped to LOINC with a one-to one correspondence but could be mapped if we alternatively mapped to multiple LOINC codes. For the subsets of exams that account for 95% and 99% of the total exam volume, the additional CT exam codes at the combined sites that could not be mapped to LOINC, RadLex, or combined LOINC/RadLex were also found to consist mostly of combination exam codes most of which could be mapped to both LOINC and RadLex terminology standards by using multiple separate primary codes. However, there were two combination exam codes that included PET (i.e., “PET/CT: Skull base to thigh” and “Whole body PET/CT”) which could not be mapped to RadLex, as the terminology at the present time does not include PET terms. In addition, the subset of exams that accounted for 99% of exam volume included the exam “CT Orbit, Sella, Posterior Fossa, or Temporal Bones without contrast,” which is a CT name set to match corresponding CPT code; this particular exam name, because it can specify an exam for any one of the four different anatomic regions, could not be mapped to LOINC or RadLex even with mapping to multiple codes.

Table 3.

Analysis of LOINC, RadLex, and Combination LOINC/RadLex coverage for exam descriptions/concept types that account for the top 80%, 90%, 95%, and 99% of exams performed across sites combined.

| 80% of exams performed | 90% of exams performed | 95% of exams performed | 99% of exams performed | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of exam types accounting for top 80%, 90%, 95% and 99% of total exams performed | 18 | 30 | 46 | 89 |

| Number (Percent) of those exam types that account for top 80%, 90%, 95% and 99% of total exams performed which could be mapped to LOINC | 18 (100%) | 29 (97%) | 42 (91%) | 80 (90%) |

| Number (Percent) of those exam types that account for top 80%, 90%, 95% and 99% of total exams performed which could be mapped to RadLex | 18 (100%) | 30 (100%) | 44 (96%) | 84 (94%) |

| Number (Percent) of those exam types that account for top 80%, 90%, 95% and 99% of total exams performed which could be mapped to combination RadLex/LOINC | 18 (100%) | 30 (100%) | 44 (96%) | 84 (94%) |

Figure 1.

Cumulative distribution curve showing the most frequently performed exams across sites over a three year period in descending order. (Note that due space constraints, the horizontal axis was truncated to the top 30 most frequently performed exam types.)

Discussion

For our particular use case, where mapping of CT test names to a standard terminology is performed as a preliminary step in the development of a multi-institutional HIE-based CDSS notification system for prior duplicate CT exams, it is most important for a terminology standard to provide mapping coverage for those exams performed with the greatest frequency across multiple sites since those are the exams that are likely to be repeated. We demonstrated that both the LOINC and RadLex standard terminologies provide sufficiently high coverage for mapping frequently performed CT exams through two complimentary analyses: (a) calculation of high concept coverage for the subset of exams that comprise up to 99% of all exams performed at the combined sites (90%, 94%, and 94% for LOINC, RadLex, and combined LOINC/RadLex terminologies), and (b) calculation of high concept token coverage at the combined sites (92%, 95%, and 96% for LOINC, RadLex, and combined LOINC/RadLex terminologies). Those exams from the “99%” subset that could not be initially be mapped to a standard terminology consisted mostly of combination exams which, except for PET/CT exams that could be not be mapped to RadLex, could all otherwise be mapped to a standard terminology by using two primary codes. Only one code from the subset of exams accounting for 99% of total exam volume (i.e., “CT Orbit, Sella, Posterior Fossa, or Temporal Bones without contrast,” which is a CT name set to match corresponding CPT code), could not be mapped to LOINC or RadLex even with mapping to multiple codes.

Another important result of our data analysis shows that a there is a highly skewed distribution of CT exams, where a handful of codes account for the majority of exams performed (21% of exam codes for combined sites account for 95% of all exams performed). This is illustrated in Figure 1, which confirms that we would only need to account for a relatively small percentage of CT exams in order to achieve high concept token coverage when mapping to a terminology standard.

A point worthy of discussion is the relatively lower concept type coverage (compared to concept token coverage) provided for by the terminology standards. The LOINC, RadLex, and combined LOINC/RadLex terminologies show concept type coverage of 70%, 75%, and 84% at the combined sites respectively (Table 1). This suggests that 16–30% of the unique local codes cannot be mapped to a terminology standard. Those unique exams that fall into this category consist mostly of highly specialized exams that are not likely to be repeated frequently or combination exams that can be mapped to a terminology standard if separated into component exams. The concept type coverage of 70% that we calculated for LOINC is lower than previously reported concept type coverages of 91% and 92% for LOINC in two other local radiology systems9,10. This may be due to our categorization of combination exam codes (e.g., CT Neck/Chest) that did not have a single corresponding LOINC or RadLex code as being a non-match for our analysis. When combination exams were mapped to multiple LOINC codes, the concept type coverage for LOINC was 90% for all sites combined, closer to coverages found in the other reports. Although high concept token coverage was the priority for our project, there are other uses where concept type coverage may be of greater importance, such as the American College of Radiology’s (ACR) CT Dose Index Registry project where the objective is to compare, in a systematic way, uniformity in variability in CT radiation dose for specific exams performed across multiple institutions16.

Although combination exams accounted for a large percentage of the codes that could not be mapped directly to single LOINC or RadLex codes, in some use cases it might be acceptable to use multiple LOINC or RadLex codes. When we mapped combination exam codes to multiple RadLex or LOINC codes, we showed that we can account for almost all exams performed with high frequency. While this might be an option for some use cases, it does not represent true one-to-one mapping and might not be appropriate in all instances.

LOINC and RadLex each have their relative strengths and weaknesses. LOINC is a robust terminology that contains more than twice the number of CT codes as RadLex. LOINC is currently endorsed by the HIT Standards committee for reporting of non-laboratory diagnostic studies for use in quality measures17. RELMA is also an excellent tool that facilitates the mapping process. Relative drawbacks of LOINC at the present time include fewer combination exam codes than RadLex (e.g., mapping “CT of the Head/Neck with IV contrast” in LOINC requires mapping to separate “CT Head” and “CT Neck” codes, whereas in RadLex it is possible to map to a single “CT Head/Neck” code). Also, LOINC at present does not code many exams to the same level of granularity as RadLex (e.g., “CT Abdomen/Pelvis with and w/o contrast and with MIP urogram” can be mapped to a specific code with the same level of granularity in RadLex but can only be mapped to the less granular “CT Abdomen/Pelvis with and w/o contrast” in LOINC). However, if one were willing to sacrifice a high level of granularity and map combination exams to separate codes, then nearly all exams performed with high frequency can be mapped to LOINC. RadLex’s strengths include its greater number of combination exam codes and codes with higher level of granularity. The major drawback of RadLex at present is its limitation to CT codes. This prevents mapping of exams that include modalities other than CT, such as PET/CT. Another limitation of RadLex is that it is a relatively new terminology that at present does not appear to have been as widely adopted as LOINC. The RadLex Playbook is currently being used by institutions participating in the ACR Dose Index Registry (DIR) project to map local CT codes to a standard nomenclature for the purposes of comparing CT radiation dose for specific exams16. However, to our knowledge, RadLex at present does not appear to be in widespread operational use beyond the DIR project. For our purposes of creating a prior CT exam CDSS alerting system, if RadLex is not widely adopted in the future, mapping solely to RadLex may impede future expansion of the system beyond a single HIE. Given these current limitations of RadLex, LOINC as presently constructed is the more appropriate choice for our particular use case. It is important to note that both terminologies are continuously undergoing revisions and adding new terms. Therefore the relative strengths and weaknesses of the terminologies are subject to change. Both terminologies have mechanisms for end-users to submit suggestions for concepts that are missing. It is also important to note that there is an effort currently underway to unify the RadLex Playbook content with LOINC18. If completed, this work would eliminate the need to choose between these two terminologies, and would likely result in a product that combines the strengths of both.

Limitations

The mapping process for this paper was fairly laborious, requiring a radiology domain expert spend approximately 100–120 hours with time divided roughly equally between LOINC and RadLex mapping. Although of RELMA’s term-by-term browser function facilitated mapping to LOINC, manual mapping to RadLex was manageable due to its fewer number of codes (342 compared with 738 for LOINC). A mapping assistant for RadLex (containing similar search functionality to RELMA) may reduce mapping time for RadLex terms. Other alternative methods for mapping besides manual review, such as ontology alignment or regular expressions, may also be useful for future studies. There is a report of creating a vector space model (VSM) program that uses cosine similarity scores of index terms in radiology reports and LOINC to assist in mapping radiology exam concept types to LOINC9. Creating a similar VSM program that produces cosine similarity scores between local test descriptions and RadLex Playbook test descriptions may in the future also aid in reducing mapping time. Furthermore, if we now map our remaining sites to LOINC alone, the amount of effort to map CT names for a particular site will be further reduced.

Another factor that added time to the mapping and analytic processes was code de-duplication, which as noted previously was performed by first mapping all local site codes to the standard terminologies and then reviewing the codes to find those that mapped to the same LOINC and RadLex codes. There is a report of the creation and use of an approximate string comparator program that semi-automates the de-duplication process for codes that differ by slight string variations19. Use of a similar program may in the future facilitate code de-duplication and also allow for code de-duplication prior to mapping thereby further reducing mapping time.

A limitation of our study is that we have currently mapped CT test names for only three institutions that participate in the New York NYCLIX HIE. A limitation of having the data solely from three sites in a large metropolitan region is that the exams performed relatively commonly at these institutions may not completely reflect the exams that are performed commonly in other sites within the HIE or in other communities.

Another limitation is that the mapping was performed by a single individual and mapping decisions are somewhat “operator dependent” because the process of mapping is not objective. The results of this study could be further validated by performing a similar analysis with two domain expert reviewers and a third acting as tie-breaker so that inter-rater reliability (Kappa scores) could be calculated.

Conclusion

In conclusion, mapping test/procedure names is a context dependent exercise that depends on the goals of the project. This study shows that both LOINC and RadLex performed reasonably well for the CT exams most commonly performed, but for more comprehensive coverage, which includes some of the less frequently performed studies, further terminology development or adaptation may be necessary.

Footnotes

At the time of this study, NYCLIX was an independent health information exchange. As of April 2012, NYCLIX merged with the Long-Island based RHIO Lipix to form a new organization, Healthix Inc.

References

- 1.Unified Medical Language System® (UMLS®) UMLS Glossary Published by U.S. National Library of Medicine, January 13, 2009. Last Updated August 15, 2012. Available at http://www.nlm.nih.gov/research/umls/new_users/glossary.html. Accessed January 30, 2013

- 2.Huff SM, Rocha RA, McDonald CJ, et al. Development of the Logical Observation Identifier Names and Codes (LOINC) vocabulary. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1998;5:276–92. doi: 10.1136/jamia.1998.0050276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McDonald CJ, Huff SM, Suico JG, et al. LOINC, a universal standard for identifying laboratory observations: a 5-year update. Clin Chem. 2003;49:624–33. doi: 10.1373/49.4.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moore T, Shapiro JS, Doles L, et al. A clinical notification service on a health information exchange platform. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2012 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shapiro JS, Mostashari F, Hripcsak G, Soulakis N, Kuperman G. Using health information exchange to improve public health. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:616–23. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.158980. Epub 2011 Feb 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin MC, Vreeman DJ, McDonald CJ, Huff SM. A characterization of local LOINC mapping for laboratory tests in three large institutions. Methods Inf Med. 2011;50:105–14. doi: 10.3414/ME09-01-0072. Epub 2010 Aug 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cornet R, de Keizer NF, Abu-Hanna A. A framework for characterizing terminological systems. Methods Inf Med. 2006;45:253–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lau LM, Banning PD, Monson K, Knight E, Wilson PS, Shakib SC. Mapping Department of Defense laboratory results to Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC) AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2005:430–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vreeman DJ, McDonald CJ. A comparison of Intelligent Mapper and document similarity scores for mapping local radiology terms to LOINC. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2006:809–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vreeman DJ, McDonald CJ. Automated mapping of local radiology terms to LOINC. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2005:769–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vreeman DJ, Stark M, Tomashefski GL, Phillips DR, Dexter PR. Embracing change in a health information exchange. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2008:768–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC®) Available at: http://loinc.org/. Accessed October 4, 2012.

- 13.Radiological Society of North America. RadLex Playbook, Release 1.0 Page. Available at: http://rsna.org/RadLex_Playbook.aspx. Accessed October 4, 2012.

- 14.Fiszman M, Shin D, Sneiderman CA, Jin H, Rindflesch TC. A knowledge intensive approach to mapping clinical narrative to LOINC. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2010:227–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vreeman DJ, McDonald CJ. Automated mapping of local radiology terms to LOINC. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2005:769–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morin RL, Coombs LP, Chatfield MB. ACR dose index registry. J Am Coll Radiol. 2011;8:288–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2010.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Health IT Policy Committee (Washington, DC) Letter to: Farzad Mostashari, MD, ScM. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC). 2011 Sep 9. Available at: http://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/standards-certification/HITSC_CQMWG_VTF_Transmit_090911.pdf. Accessed July 31, 2013

- 18.Radiological Society of North America and National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering. Project Title: The Unification of RadLex and LOINC. Notice of intent posted 2013 Mar 9. Available at: http://1.usa.gov/148mXma. Accessed July 31, 2013

- 19.Vreeman DJ. Keeping up with changing source system terms in a local health information infrastructure: running to stand still. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2007;129:775–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]