Abstract

Psychometric instruments, inventories, surveys, and questionnaires are widely accepted tools in the field of behavioral health. They are used extensively in primary and clinical research, patient care, quality measurement, and payor oversight. To accurately capture and communicate instrument-related activities and results in electronic systems, existing healthcare standards must be capable of representing the full range of psychometric instruments used in research and clinical care. Several terminologies and controlled vocabularies contain representations of psychological instruments. While a handful of studies have assessed the representational adequacy of terminologies in this domain, no study to date has assessed content coverage. The current study was designed to fill this gap. Using a sample of 63 commonly used instruments, we found no concept in any of the three terminologies evaluated for more than half of all instruments. Of the three terminologies studied, SNOMED CT (Standard Nomenclature of Medicine – Clinical Terms) had the greatest breadth, but least granular coverage of all systems. While SNOMED CT contained concepts for over one third (36%) of the instrument classes in this sample, only 11% of the actual instruments were represented in SNOMED CT. LOINC (Logical Observation Identifiers, Names, and Codes), on the other hand, was able to represent instruments with the greatest level of granularity of the three terminologies. However, LOINC had the poorest coverage, covering fewer than 8% of the instruments in our sample. Given that instruments selected for this study were selected on the basis of their status as gold standard measures for conditions most likely to present in clinical settings, we believe these results overestimate the actual coverage provided by these terminologies. The results of this study demonstrate significant gaps in existing healthcare terminologies vis-à-vis psychological instruments and instrument-related procedures. Based on these findings, we recommend that systematic efforts be made to enhance standard healthcare terminologies to provide better coverage of this domain.

Introduction

Psychometric instruments, inventories, surveys, and questionnaires are widely accepted tools in the field of behavioral health1. In patient care, they are used to screen for and diagnose mental health conditions, to obtain information about the nature and severity of symptoms, and to select appropriate treatments. They are also used to monitor patient response to treatment, and to detect adverse reactions2. In primary research, psychometric instruments are used to screen participants and to operationalize study variables. In clinical research, they are used to assess the efficacy and effectiveness of specific interventions and to compare the relative effectiveness of two or more interventions. Finally, in quality improvement and general oversight, psychometric instruments are used to identify gaps in quality and guide performance improvement programs.

As the primary source of objective data upon which all evidence-based practice in this domain is grounded, the ability to capture, aggregate, and share instrument-related information is a high priority for both researchers and clinicians3,4,5. While a number of studies exist describing the adequacy of representations in this domain, no study to date has evaluated the coverage of instruments in any healthcare terminology. The current study was undertaken to fill this gap. Specifically, this study evaluates three clinical terminologies available to users of electronic information systems for capturing structured information related psychological assessments. The first two terminologies, SNOMED CT and LOINC, are designed for use in the clinical domain. The third, QS Terminology, is designed specifically for use in medical and behavioral research. Each of these three terminologies allows for the structuring of data related to a slightly different set of assessment-related elements and procedures. All three, however, contain representations corresponding to the psychological assessment instrument entity.

The primary aim of the current study is to evaluate the coverage of these three terminologies for psychological assessment instruments currently used in research and clinical practice. A secondary aim of this study is to evaluate the consistency with which these terminologies currently represent psychological instruments.

Background

In 2006, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) published an extensive report arguing that current efforts to improve the quality of healthcare must be extended to behavioral health6. A key recommendation of this report is that the health information infrastructure be enhanced to accommodate the needs of behavioral healthcare6. In this report, the IOM specifically identifies the creation of standard terminologies for all commonly used interventions and assessment methods as a key element in building this infrastructure. Moreover, in 2009, the United States Government passed legislation requiring healthcare providers seeking reimbursement for federally funded services to use electronic health records that comply with minimum standards. Among these standards are the requirement that all assessment data submitted to external organizations be coded using a pre-specified set of standard identifiers.

Currently, there are three standard terminologies available for capturing, aggregating and communicating psychological assessment data obtained in clinical and research processes. These terminologies are SNOMED CT, LOINC, and CDISC’s Questionnaire (QS) Terminology. SNOMED CT, the Standard Terminology for Medicine – Clinical Terms, is a clinical terminology used for capturing, aggregating, analyzing and sharing granular clinical data that span virtually the entire range of healthcare. SNOMED CT contains more than 300,0007 concepts across a wide range of domains including diseases, anatomical structures, clinical findings, procedures, social contexts, devices and biological substances8. LOINC® (Logical Observations, Identifiers, Names and Codes) is a terminology consisting of a set of universal codes for laboratory tests and other types of clinical observations and measures9. In 2000, LOINC introduced the SURVEY class to accommodate clinical assessments3, which includes questionnaires, surveys, and other form-based assessment instruments. Currently, LOINC includes entries for thirteen psychological assessment instruments, six of which are modeled as components of the mental health survey class (SURVEY.MLTHLTH).

While SNOMED and LOINC are designed specifically for use in clinical information systems used at the point of care, the third terminology, Questionnaire (QS) Terminology, is designed specifically for use in clinical research. QS Terminology was developed by the Clinical Data Interchange Standards Consortium (CDISC), a non-profit Standards Development Organization (SDO) whose primary objective is to support the capture and exchange of data in “all types of medical research”10. QS Terminology is one standard in a suite of several that are designed to support structured data collection at all stages of the research process, from protocol development to analysis and reporting of results. These standards are specifically designed to support the acquisition, exchange, and submission of clinical research data10.

Both SNOMED CT and LOINC are endorsed by the United States government for use in electronic health records (EHRs). As part of the HITECH (Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health) Act of 200911, the government mandated that electronic health record systems used by healthcare delivery organizations meet requirements for the ‘meaningful use’ of health information. To meet this requirement, EHRs must code relevant clinical data using approved terminologies. SNOMED CT and LOINC are two terminologies specifically designated by the US government as acceptable for coding granular clinical data (i.e., data that cannot be represented using standard diagnostic and procedural coding systems). While both terminologies contain concepts for coding psychological assessments, the United States’ national strategy is to represent such instruments, along with all other types of measures, in LOINC12.

Very little research, to date, has focused on the role of standard terminologies for representing psychological assessments. What has been published in this domain has focused primarily on the adequacy of representations in existing terminologies. This work has focused largely on LOINC. Four key studies have been performed addressing standardized assessments in LOINC. Two of these studies address modifications to LOINC necessary to accommodate assessment instruments. The first of these studies was performed by Bakken et al3 in 2000. This paper introduced a new LOINC class to accommodate psychological assessments, and proposed extensions to the six core axes used to represent entities in LOINC3. The second study, performed by White et al4, addressed the important issue of instrument versioning as it relates to psychometric properties of instruments and its impact on representation of assessments in LOINC. These authors proposed four modifications to LOINC they believed necessary to support the accurate identification and disambiguation of assessment instruments. In addition, two of the four publications addressed LOINC content specifically as it relates to standardized assessments3,4. Neither study focused specifically on psychological assessment instruments, nor did either study address coverage. To date, no study has systematically evaluated the coverage of instruments in currently available terminology products. Furthermore, our literature search did not return a single article addressing either the representation, or coverage, of psychological assessments in SNOMED CT.

Methods

Datasources

Data for the current study came from healthcare web sites and three standards development organizations (SDOs). The web sites used for the current study were the National Institute of Mental Health13 (NIMH), and those of several organizations dedicated to the research and treatment of mental health conditions. Organization web sites were selected as the primary data source for identifying both target mental health conditions and high quality, commonly used condition-specific instruments. We selected web sites as the primary data source because we believed them to the most valid and timely source for this information. The terminologies evaluated in this study are SNOMED CT version 2012.8.0270, LOINC version 2.40, and CDISC’s QS Terminology (Table 1).

Table 1:

Terminology Datasources

| Terminology | Organization | Target Information System | Mandate |

|---|---|---|---|

| LOINC | Regenstrief | Electronic Health Records | HITECH Meaningful Use |

| SNOMED CT | IHTSDO1 | Electronic Health Records | HITECH Meaningful Use |

| QS Terminology | CDISC2 | Clinical Research Information Systems | Industry Consensus Standard |

International Healthcare Terminology Standards Development Organization;

Clinical Data Interchange Standards Consortium

Procedure

Using the NIMH list of mental health conditions as a source, we identified sixteen disorders. To this list, we added four additional instrument categories we believed to be particularly relevant to mental health (Appendix C). For each condition or construct, we selected instruments based on recommendations provided by organizations dedicated to the study or treatment of the target condition. Our goal was to select a set of 3 to 4 instruments for each condition. This resulted in a master set of 63 instruments (Appendix D).

For the current study, we evaluate ten distinct information elements related to instruments. These elements, along with the algorithm used to code them, are depicted in Table 2. The primary unit of analysis for this study is the discrete assessment instrument. We define an assessment instrument as a named collection of observations and observation metrics. It is a concrete entity that is fully defined by its component elements (i.e., scales, subscales, items) and the methods used to generate an observation (i.e., item response scale and metric). Consequently, when changes are made to either the instrument components (e.g., observations are added, deleted, or substantially modified) or the method by which observations are evaluated and quantified (e.g., response scale changes), the collection is assumed to represent a new instrument.

Table 2:

Instrument Information Elements and Coding Algorithms

| Information Element | Coding Algorithm |

|---|---|

| Instrument Class | The terminology contains a concept for representing the instrument class. |

| Instrument Instance | The terminology contains a concept for representing the specific version of the instrument in the sample. |

| Instrument Scale | If items in the instrument are organized into named scales, the terminology contains a concept for representing at least one of the scales in the instrument. |

| Instrument Subscale | If items in the instrument are organized into scales, and one or more of the scales is organized into subscales, the terminology contains a concept for representing at least one of the subscales in the instrument. |

| Instrument Item | The terminology contains a concept for representing at least one item in the instrument. |

| Instrument Response Items | The terminology contains a concept for representing at least one item response in the instrument. |

| Instrument Response Values | The terminology contains a concept for representing at least one value for one item response in the instrument. |

| Instrument Score | The terminology contains a concept for representing at least one score generated by the instrument. |

| Instrument Administration | The terminology contains a concept for representing administration of the specific instrument. |

| Instrument-Related Findings | The terminology contains a concept for representing one or more findings specifically related to use of the instrument. |

We define an instrument class as the more general class of observations from which specific instruments (instrument versions) are derived. The instrument class can be thought of as the “base” instrument upon which one or more specific instrument versions are based. The ‘Beck Depression Inventory’ (BDI) is an example of an instrument class. While the base instrument is not simply the first instrument in a series of versions or revisions, many key instrument attributes (e.g., construct measured, target population, etc.) are defined by the first instrument. In this sense, the first instrument can be thought of as the class template from which future instances are derived.

Using the example of the BDI, one class (i.e., BDI) and four instruments (i.e., BDI-I, BDI-IA, BDI-II, and BDI-PC) can be identified. The first three instruments represent a refinement (or adaptation) of the instrument over time. The fourth instrument, the BDI-PC, represents a modification that has been made for use in a new setting. The boundary between instrument classes can sometime become blurry, as when an instrument is adapted from a previous instance, and the new instance is sufficiently different from the original class that it becomes a new class. However, this case did not apply to any of the instruments in the current sample, and is therefore is not addressed further in the current analysis.

The next five information elements correspond to instrument components. These are instrument scales, subscales, items, item responses, and item response values. An instrument scale is defined as a named collection of observations within the instrument, and a subscale as a named collection of observations within a scale. Instrument items are defined as the discrete observations that are coded. Item responses are defined as the discrete set of responses that can be associated with the observation. Item response values are defined as the specific code (nominal or quantitative) that can be associated with the item response14. Instrument scores are defined as quantitative or qualitative scores derived from one or more scales, subscales or observations. For purposes of the current study, we evaluated only the score associated with the overall instrument (i.e., total or summary score).

In addition to concepts related to the physical instrument, we also assessed whether the terminology contained concepts related to instrument administration and instrument-specific findings. Instrument administration is defined as the activity during which the set of observations contained in the instrument are made. Instrument-specific findings are defined as clinical observations that are made on the basis of results obtained by administering the instrument (e.g., ‘decrease in depression score’, ‘no change in suicidal ideation’).

Using the ten information elements identified above, we coded each terminology according to whether or not it contained a corresponding concept for each instrument. This strictly binary method differs slightly from previous methodologies used in coverage studies. In a coverage analysis of clinical concepts found in medical records, for example, Chute and colleagues15 used a dimensional model in which they rated each concept along a continuum representing closeness of match to the target concept. In the Chute study, each concept was scored on a scale of 0 (no match) to 2 (exact match). Wasserman and Wang16 took a slightly different approach in their coverage analysis. Examining concepts required for implementing Computerized Provider Order Entry (CPOE), these authors used a 4-level coding scheme that essentially quantified the effort required to add the target concept to the terminology. In the current study, we chose to explicitly define the specific instrument-related information element we were targeting, and to code the corresponding concept in a strictly binary (i.e., present/not present) manner. We used this approach because we felt it provided an accurate assessment of the value of the terminology from the perspective of the end user. That is, an end user would either find a useable concept, or not.

Using this scheme, each of the three terminologies was searched for concepts corresponding to the ten target information elements for each of the 63 instruments in the sample. Interrater reliability was calculated based on a sample of 15 instruments (150 target concepts) coded by a second reviewer (TJA) and found to be adequate (κ = 0.92). A review of discrepancies between raters revealed that most occurred in distinguishing between instrument instance concepts and the instrument class concept in SNOMED CT. Interrater agreement for instrument instance and instrument class concepts was lower than overall agreement (κ = 0.88). Interrater agreement for SNOMED CT was also lower (κ = 0.89).

Results and Discussion

Terminology Coverage

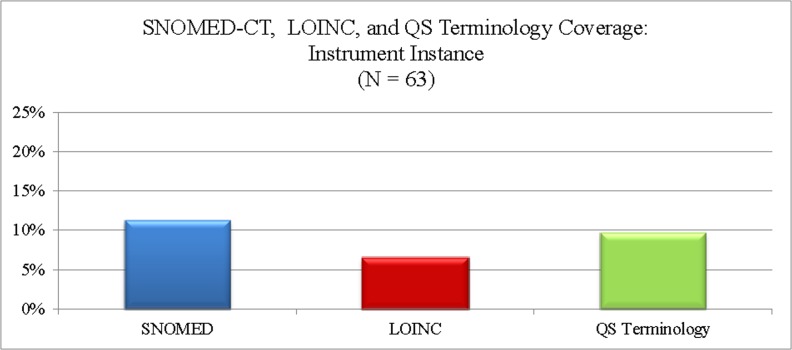

Coverage of instrument instance concepts in all three terminologies was poor. These three terminologies covered an average of 5.6 (9.1%) instrument instances in our sample. Of the three terminologies evaluated, SNOMED CT had the best coverage (n = 7, 11.3%) and LOINC the poorest (n = 4, 6.5%).

A summary of concept coverage by terminology is presented in Figure 1. SNOMED CT covered the largest number and widest range of overall instrument-related concepts, containing 48 concepts across five of the ten instrument concept categories. CDISC’s QS Terminology contained the greatest number of instrument item concepts, but covered the smallest range of concepts. LOINC was the only terminology providing coverage of instrument response concepts. SNOMED CT was the only terminology providing coverage of instrument administration or instrument findings concepts (Table 3).

Figure 1:

Instrument and Instrument Components Representation

Table 3:

Instrument Coverage by Terminology

| Attribute | SNOMED CT | LOINC | QS Terminology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Instrument Class | 22 (35%) | 02 (3%) | - |

| Instrument Instance | 07 (11%) | 04 (6%) | 06 (10%) |

| Instrument Scale | - | - | - |

| Instrument Subscale | - | - | - |

| Instrument Item | - | 03 (5%) | 06 (10%) |

| Instrument Response Items | - | 03 (5%) | - |

| Instrument Response Values | - | - | - |

| Instrument Score | 08 (13%) | 1 (2%) | - |

| Instrument Administration | 09 (15%) | - | - |

| Instrument Related Finding | 1 (2%) | - | - |

Instrument Class and Instance

While SNOMED CT contained the greatest number of instrument-related concepts in our sample, most of these concepts are not specific enough to be used to code or capture clinical data. Instead, these concepts are best used as organizing concepts under which missing child concepts can be modeled (Table 4). For example, 22 (46%) of the 48 concepts covered by SNOMED CT were instrument class concepts. Moreover, of the seven instrument instance concepts covered by SNOMED CT, only one was modeled with sufficient detail to ensure that the concept remains unambiguous with the introduction of future instrument versions. That is, the concept for only one instrument in the sample contained sufficient versioning information to use the instrument concept to unambiguously identify a particular instrument.

Table 4:

SNOMED CT Coverage of Instrument Class and Not Instruments

| Instrument Class | Missing SNOMED CT Instrument Concepts |

|---|---|

| beck depression inventory (assessment scale) | beck depression inventory version 1 (assessment scale) |

| beck depression inventory version 1a (assessment scale) | |

| beck depression inventory version 2 (assessment scale) | |

| beck depression inventory primary care version (assessment scale) |

Instrument Component

There was no coverage of instrument scale concepts in any of the three terminologies for any of the instruments in our sample. A detailed review of concepts in each terminology, however, confirmed that both LOINC and SNOMED are capable of representing this class of concepts. In fact, we found several instances of instrument scale concepts in SNOMED CT. Interestingly, CDISC’s QS Terminology provided better coverage of instrument element concepts in our sample than did LOINC. LOINC, however, was the only terminology that provided any coverage of item response concepts.

Instrument Administration

Both LOINC and QS Terminology codes can be used to indicate that a particular instrument or instrument item was administered. However, neither terminology provides codes corresponding to the concept of having administered an instrument. SNOMED CT, on the other hand, contains discrete codes for instrument administration. These codes are modeled in SNOMED CT as child concepts of concepts in the ‘procedure by method’ and ‘provider-specific procedure’ hierarchies. Both of these hierarchies are in turn children of the top level ‘procedure’ hierarchy, which represents activities performed during the routine delivery of healthcare17. Ten (77%) of the 13 instruments with corresponding administration procedure concepts in SNOMED CT were modeled as child concepts of ‘assessment using assessment scale’, and three (23%) were modeled as child concepts of ‘psychologic test’ (Table 5).

Table 5:

SNOMED CT Representation of Instrument Administration Procedure

| SNOMED CT Hierarchy | Sample Concepts |

|---|---|

| Provider-specific procedure | Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI-2) |

| Psychologic evaluation or test procedure | Rorschach |

| Psychologic test | Thematic Apperception Test (TAT) |

|

| |

| Procedure by method | Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) |

| Evaluation procedure | Eating Disorder Examination (EDE) |

| Assessment using assessment scale | Eating Disorders Inventory (EDI) |

| Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) | |

| Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) | |

| Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ) | |

| Psychotic Symptom Rating Scale (PSYRATS) | |

Interestingly, while SNOMED CT included concepts representing the administration of 17 distinct instruments under the concept ‘psychologic test’, it contained a concept representing the corresponding instrument for only 8 (47%) of the instrument administration procedures modeled. Finally, SNOMED CT was unique among the three terminologies in our study in that it was the only terminology that included any concept related to interpretation of instrument results. Admittedly, we found only two qualifying concepts, and both referred to the same instrument (i.e., the ‘Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (assessment scale)’. These concepts were ‘decline in Edinburgh postnatal depression scale score (finding)’, and ‘decline in Edinburgh postnatal depression scale score at 8 months (finding)’.

Conclusion

The results of this study demonstrate significant gaps in existing healthcare terminologies for psychological instruments and instrument-related activities. In this study, we evaluated three standard terminologies and found no concept in any of the three terminologies for more than half of all instruments evaluated. On average, these three terminologies covered fewer than 10% of the instrument instances in our sample, with a range of 7% (LOINC) to 11% (SNOMED CT).

The primary limitation of this study is that many of the instruments included in our sample are copyrighted and/or commercial instruments. Consequently, they may not exist in standard terminologies due to an unwillingness of the copyright holder to release the copyright. Similarly, the results of this study cannot be generalized to all standardized assessment instruments. Assessment instruments cover a broad range of healthcare domains, beyond just mental health. The instruments selected for the current study were all psychometric instruments. It is quite possible that coverage of standardized assessments for another domain (e.g., oncology or neuropsychology) would yield a different result.

However, given that instruments selected for this study were selected on the basis of their status as gold standard measures for conditions most likely to present in clinical settings, we believe these results may underestimate the actual coverage of psychometric instruments provided by current healthcare terminologies. Based on these findings, we recommend that systematic efforts be made to enhance standard terminologies to provide better coverage of this domain. Specifically, instruments currently used in research and routine clinical care should be identified, and inclusion of the identified instruments in at least one standard terminology made a priority.

References

- 1.White GW, Jellinek MS, Murphy JM. The use of rating scales to measure outcomes in child psychiatry and mental health. In: Baer L, Blais MA, editors. Handbook of clinical rating scales and assessment in psychiatry and mental health. New York, NY: Humana Press; 2010. pp. 175–94. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lambert MJ. Prevention of treatment failure : the use of measuring, monitoring, and feedback in clinical practice. 1st ed. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bakken S, Cimino JJ, Haskell R, et al. Evaluation of the clinical LOINC (Logical Observation Identifiers, Names, and Codes) semantic structure as a terminology model for standardized assessment measures. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2000;7:529–38. doi: 10.1136/jamia.2000.0070529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White TM, Hauan MJ. Extending the LOINC conceptual schema to support standardized assessment instruments. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2002;9:586–99. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vreeman DJ, McDonald CJ, Huff SM. Representing Patient Assessments in LOINC(R). AMIA Annu Symp Proc; 2010; 2010. pp. 832–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Institute of Medicine . Improving the quality of health care for mental and substance-use conditions. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.SNOMED CT Components 2012. (Accessed November 18, at http://www.ihtsdo.org/snomed-ct/snomed-ct0/snomed-ct-components/.)

- 8.Organisation TIHTSD . SNOMED-CT User Guide. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vreeman DJ, McDonald CJ, Huff SM. LOINC(R) - A Universal Catalog of Individual Clinical Observations and Uniform Representation of Enumerated Collections. Int J Funct Inform Personal Med. 2010;3:273–91. doi: 10.1504/IJFIPM.2010.040211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mission & Principles Clinical Data Interchange Standards Consortium. 2012. (Accessed November 15, 2012, at http://www.cdisc.org/mission-and-principles.)

- 11.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2012. Meaningful Use. (Accessed November 18, 2012, at http://www.healthit.gov/policy-researchers-implementers/meaningful-use.) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Humphreys B. 2012. Personal Communication. In;

- 13.Mental Health Topics 2012. (Accessed August 12, 2012, at http://www.nimh.nih.gov/index.shtml.)

- 14.Poldrack R. Cogntive Atlas: A Collaboratively Developed Cognitive Science Ontology Contributor's Guide 2009. University of Texas; Austin: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chute CG, Cohn SP, Campbell KE, Oliver DE, Campbell JR. The content coverage of clinical classifications. For The Computer-Based Patient Record Institute's Work Group on Codes & Structures. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1996;3:224–33. doi: 10.1136/jamia.1996.96310636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wasserman H, Wang J. An applied evaluation of SNOMED CT as a clinical vocabulary for the computerized diagnosis and problem list. AMIA Annu Symp Proc; 2003. pp. 699–703. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.IHTSDO . International Release. Jan, 2011. Standard Nomenclature of Medicine-Clinical Terms. [Google Scholar]