Abstract

Context-aware links between electronic health records (EHRs) and online knowledge resources, commonly called “infobuttons” are being used increasingly as part of EHR “meaningful use” requirements. While an HL7 standard exists for specifying how the links should be constructed, there is no guidance on what links to construct. Collectively, the authors manage four infobutton systems that serve 16 institutions. The purpose of this paper is to publish our experience with linking various resources and specifying particular criteria that can be used by infobutton managers to select resources that are most relevant for a given situation. This experience can be used directly by those wishing to customize their own EHRs, for example by using the OpenInfobutton infobutton manager and its configuration tool, the Librarian Infobutton Tailoring Environment.

Introduction

The term “clinical decision support” has long been synonymous with automated alerts and reminders generated by electronic health records (EHRs) in response to events such the entry of a clinician’s orders or the arrival of a diagnostic test result. Recently, there has been increased interest in user-initiated context-sensitive links to relevant online knowledge sources, commonly known as infobuttons.[1] In the US, for example, the federal government considers use of infobuttons by clinicians to represent evidence of “meaningful use” of EHRs and requires their implementation to satisfy EHR certification requirements.[2] Incorporating context-aware links from EHRs to knowledge resources is becoming relatively straightforward, thanks in part to the need for EHR vendors to provide such capability, in part to the willingness of knowledge resource vendors to configure their products to respond to context-specific information requests, and in part to the development of an HL7 standard for passing contextual information from EHRs to knowledge resources.[3] As a result, creating “hard-wired” links between some component of an EHR user interface and a particular, predetermined resource is readily achievable today.

However, many studies have shown that, when it comes to knowledge resources, there is rarely a one-size-fits-all solution for any given clinical situation. So, for example, a clinician reviewing the result of laboratory test measuring the concentration of an antibiotic in a patient’s blood might need information from a laboratory manual, an infectious disease review article, or a toxicology textbook. The need for a more dynamic approach to resource selection can be achieved using an infobutton manager (IM) or similar system that uses aspects of the user’s clinical context to choose from a set of resources and customize them based on parameters describing the patient, the user, and the anticipated information need. We have previously described one such IM, called OpenInfobutton, that is HL7-compliant and freely available.[4] Institutions that choose to integrate their EHRs with OpenInfobutton can make use of the Librarian Infobutton Tailoring Environment (LITE) to construct the OpenInfobutton knowledge base in order to specify which resources should be made available to their users in which situations.[4]

While, several publications describe the mechanisms for addressing issues related to configuring an IM,[4] implementing the HL7 standard,[5] and coping with the terminology issues [5, 6], they do not describe what resources to specify for a given clinical situation. Many studies do describe resource selection by clinicians,[7–11] including those using infobuttons,[12–15] but they do not describe how to specify the context-specific attributes that are needed for selecting resources that clinicians want in the settings where they are most wanted.

The purpose of this paper is to summarize the experience of several IM implementations from disparate institutions to enumerate the specific resources that the maintainers of these systems have found to be valuable for their users, to identify the HL7 context parameters that have actually been brought to bear on the resource selection used by existing IMs, and to examine the actual usage statistics that support their choices. We believe that institution personnel (medical librarians or those acting in that role) will find this experience useful for integrating knowledge resources into their own EHRs as well as provide a guide for future IM developers.

Background

Customizing an Infobutton Manager

The person (whom we will refer to as the librarian) charged with specifying how an infobutton manager will respond when an EHR user selects an infobutton link must make two kinds of decision (see Figure 1). First, the librarian must decide what resources are likely to be needed in a given situation. Implicit in this decision, is an understanding of the actual information needs. For example, if a user is choosing a therapy, will that user want the latest evidence related to disease management? In that case, a resource such as PubMed or the Cochrane Collection might be appropriate. Or perhaps the user has chosen a particular medication but has a question about drug dosing. In that case, perhaps a commercial drug knowledge resource, to which the institution subscribes, will be useful.

Figure 1:

Knowledge specifications for an Infobutton Manager. The librarian first decides which resources are generally appropriate for a given clinical task (solid arrows) and then further refines the selection criteria based on specific values of the HL7 context parameters (boxes with dashed lines). Three parameters (in addition to “Task”) are shown; the standard specification includes many others as well.

Once a resource is selected as being generally relevant to a clinical task, the librarian may wish to further narrow the resources selected to be those that best fit some details of the clinical context. Is the patient a child? Then pediatric resources may be the best choice. Is the patient a female of child-bearing age? If so, then perhaps resources that can provide information about pregnancy risk and breast-feeding will be useful. What if the patient is also the system user? In that case, the IM might choose to offer the consumer-oriented MedlinePlus Connect instead of the more technical PubMed.

The HL7 standard provides parameters for all of these aspects of the clinical context, and more. It is up to the librarian to take advantage of these to winnow down, from all the possible resources that can be offered to the user, those that will be most relevant.

Existing Infobutton Managers

We included four IMs (integrated into over 16 EHRS) in our survey of resources used and context-specific selection criteria. The Columbia University IM evolved into its current form in 2002,[16] with a user interface redesign in 2007.[17] It has been integrated with two EHRs at New York-Presbyterian Hospital (WebCIS and Eclipsys Sunrise Clinical Manager), the New York State Psychiatric Institute, and the Regenstrief Medical Records System (although only data from the first of these four systems is used in the current study). Log file transaction data from 2008 to 2012 were selected for this study.

Partners Healthcare’s IM, called KnowledgeLink, was first developed in 2003 and is now embeded within 10 different clinical workflow applications across the enterprise (an outpatient EHR, two inpatient OE systems, two pharmacy apps, a results viewer [which itself is embedded in many other apps], a medication reconciliation application, a search engine, and two library portals). Log file transaction data from February 2013 for all ten EHRs were analyzed for this study.[18]

Intermountain Healthcare’s IM has been in place since the early 2000’s and has been used in three clinical information systems that span inpatient and outpatient care.[19] The primary domains of use for infobuttons at Intermountain include medication review and ordering, problem list review, lab results review, and microbiology data. Intermountain is in the process of transitioning its IM to be based off the OpenInfobutton project. Data for this project were taken from monitoring logs for the past five years (February 2008 - February 2013).

OpenInfobutton evolved from an earlier IM at the Intermountain Healthcare[19] into an open source, HL7-compliant IM with funding from the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). It is currently maintained by a group of collaborating institutions led by investigators at the University of Utah. The source code is available through VHA’s Open Source EHR Agent (OSEHRA) framework under APACHE 2.0 license; however, the University of Utah installation is freely available for use by other institutions. OpenInfobutton has been integrated with EHR systems at several health care organizations, such as the VHA, the University of Utah, Intermountain Healthcare, and Duke University. Implementation at other collaborating institutions is underway. For example, the University of Washington (UW), also included in this study, has utilized the OpenInfobutton IM in a pilot study exploring the delivery of pharmacogenomics (PGx) knowledge to support drug therapy individualization.[20]

Methods

We obtained three sets of data from each IM:

A list of resources provided to the EHR users, including whether the resource is called using the HL7 standard, and any specific parameter values that are passed to the resource to convey the user’s context or information need

The set of context parameter values that are specified in the IM knowledge base to indicate when a resource should be selected for presentation to the user; together, the context parameter values and the particular resource are referred to as context-specific links (CSLs)

Usage statistics indicating the number of times that any user chose a particular resource in a particular context; for this analysis we considered only those resources that accounted for at least 0.5% of the usage data to be significant

Each IM organizes its knowledge differently, in ways that reflect their origins prior to the availability of the HL7 standard. For example, the Columbia IM uses the Medical Entities Dictionary[21] to expand the “Main Search Criteria” (typically, the concept in the EHR display with which an infobutton icon is associated) to include concepts that are semantically related (e.g., “serum albumin test” is expanded to include “albumin” and “hypoalbuminemia”). IMs also may include institution-specific values for HL7 parameters (such as “neonatal cardiac care unit” as a care setting, or “informationist” as a user type) that are not covered by the HL7 standard. Nevertheless, we attempted to convert all non-HL7 parameter values into their nearest equivalent to facilitate inter-institutional comparisons and to make the listing as relevant as possible for readers interested in adopting them for use in their own institution.

Results

Each site reported data for a period during which IM parameters had remained relatively stable, ranging from one month (Partners Healthcare; 105,306 instances) to five years (Columbia; 19,703 instances). The number of significant resources (at least 0.5% of usage at the respective institution) ranged from five (VHA) to 14 (Columbia), with a total of 60 instances of 44 unique resources. Table 1 shows the names and Uniform Resource Locators (URLs) for these resources and indicates which institutions are linking to them.

Table 1:

Names and URLs of resources accessed by infobutton managers by the institutions in this study.

Notes: HL7=Health Level 7, CU= Columbia University, PH=Partners Healthcare, UU=University of Utah, DU=Duke University, VHA=Veterans Health Administration, UW=University of Washington.

Full table is available at: http://www.dbmi.columbia.edu/~ciminoj/amia13/Appendix.xls

The CSLs were related to ten clinical tasks, including laboratory results review (LABRREV), laboratory test order entry (LABOE), medication list review (MLREV), medication orders (MEDOE), microbiology results review (MICRORREV), radiology report review (RADREPREV), pathology report review (PATREPREV), diagnosis list entry (DIAGLISTE), cardiology report review (no HL7 equivalent), and microorganism antibiotic sensitivity results review (no HL7 equivalent). Table 2 shows the frequency with which users selected various resources during two types of clinical tasks, LABRREV and MLREV/MEDOE (combined due to substantial overlap in these clinical tasks at most of the institutions). The full table is shown in the Appendix at http://www.dbmi.columbia.edu/~ciminoj/amia13/Appendix.xls.

Table 2:

Frequency of resources selected by users at four institutions, by clinical task (LABREV=Laboratory Results Review; MEDOE=Medication Order Entry/Medication List Review)

| Task Context | Resource | Columbia (N=5833) | Partners (N=7511) | Intermountain (N=148842) | U Wash (N=98) | U Utah | Duke | VHA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LABREV | ARUP | 1.18% | ||||||

| LABREV | ARUP Consult/Lexi-Comp | 7.68% | 12.88% | |||||

| LABREV | Clineguide | 44.79% | ||||||

| LABREV | CPMC Lab Manual | 20.97% | ||||||

| LABREV | Dxplain | 4.82% | ||||||

| LABREV | ePKgene | 58.16% | ||||||

| LABREV | 5.58% | |||||||

| LABREV | Harrisons | 5.90% | ||||||

| LABREV | Lab Tests Online | 14.02% | ||||||

| LABREV | Lab Tests Online | 2.08% | ||||||

| LABREV | Mayo Clinic | 0.67% | ||||||

| LABREV | MDConsult | 3.38% | 35.15% | |||||

| LABREV | MedLinePlus | 3.40% | 1.21% | |||||

| LABREV | Micromedex LabAdvisor | 13.75% | 27.56% | |||||

| LABREV | National Guidelines | 15.12% | ||||||

| LABREV | Partners Handbook | 16.72% | ||||||

| LABREV | PharmGKB Gene Details | 36.73% | ||||||

| LABREV | PubMed | 5.35% | 3.21% | |||||

| LABREV | Stedmans Medical Dictionary | 21.21% | ||||||

| LABREV | Up to Date | 11.21% | 22.15% | |||||

| LABREV | UW Online Laboratory Test Guide | 5.10% | ||||||

| MEDOE | ARUP | 2.33% | ||||||

| MEDOE | ARUP Consult/Lexi-Comp | 27.46% | 2.12% | |||||

| MEDOE | BWH Drug Guidelines | 8.38% | ||||||

| MEDOE | CDC Summaries | 1.35% | ||||||

| MEDOE | Clinical Pharmacology | 9.30% | ||||||

| MEDOE | Cochrane reviews | |||||||

| MEDOE | Dynamed | X | X | |||||

| MEDOE | eMedicine | 9.46% | ||||||

| MEDOE | ePKgene | 14.86% | ||||||

| MEDOE | Geriatric Drug Monographs | 0.05% | ||||||

| MEDOE | 0.42% | |||||||

| MEDOE | Harrisons | 2.84% | ||||||

| MEDOE | Healthwise | X | ||||||

| MEDOE | Mayo Clinic | 0.16% | ||||||

| MEDOE | MDConsult | 0.26% | 8.55% | |||||

| MEDOE | MedlinePlus | 0.26% | 0.29% | X | X | X | ||

| MEDOE | Micromedex | 58.41% | 84.01% | 84.37% | ||||

| MEDOE | National Guidelines | 2.84% | ||||||

| MEDOE | Partners Handbook | 1.27% | ||||||

| MEDOE | PLoS Currents | 48.65% | ||||||

| MEDOE | Pubmed | X | X | X | 25.68% | |||

| MEDOE | Stedmans Medical Dictionary | 1.61% | ||||||

| MEDOE | UpToDate | 6.12% | 1.68% | X | X | X | ||

| MEDOE | VisualDx | 6.58% | X | |||||

Notes: Full table is available at: http://www.dbmi.columbia.edu/~ciminoj/amia13/Appendix.xls

In addition to the clinical task, IMs allow customization of CSLs to restrict resource selection based on the user role, the intended recipient (provider or patient), the encounter setting (inpatient, outpatient, emergency department, etc.) and the age and gender of the patient (see HL7 specification for full list of parameters and allowed values[3]). Table 3 shows the degree to which each institution customized their CSLs to make use of these parameters.

Table 3:

HL7 Infobutton Parameters Used by Infobutton Managers from Institutions in this Study

| Context parameters | Columbia | Partners | Intermountain | U Utah | Duke | VHA | U Wash |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| taskContext | DIAGLISTE diagnosis list entry MEDOE medication order entry MLREV medication list review LABRREV laboratory results review LABOE laboratory test order entry MICRORREV microbiology results review PATREPE pathology report review RADREPE radiology report review |

LABRREV laboratory results review MEDOE medication order entry MLREV medication list review PROBLISTREV problem list review PROBLISTE problem list entry |

MEDOE medication order entry MLREV medication list review PROBLISTREV problem list review PROBLISTE problem list entry LABRREV laboratory results review LABOE laboratory test order entry MICRORREV microbiology results review |

MEDOE medication order entry MLREV medication list review PROBLISTREV problem list review PROBLISTE problem list entry |

MEDOE medication order entry MLREV medication list review PROBLISTREV problem list review PROBLISTE problem list entry |

MEDOE medication order entry MLREV medication list review PROBLISTREV problem list review PROBLISTE problem list entry |

MEDOE medication order entry LABRREV laboratory results review |

| mainSearchCriteria | 407314008 Enzyme inhibitor 29303009 Electrocardiogram 404684003 Clinical finding 108252007 Laboratory procedure 363787002 Observable entity 410607006 Organism 373873005 Pharmaceutical / biologic product |

Some criterion-specific rules for matching to particular resources | Capecitabine, Carvedilol, Clopidogrel, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP2D6, DPYD, Irinotecan, Metoprolol, Propafenone, Tamoxifen, Thioguanine, TPMT, UGT1A1, Warfarin | ||||

| subTopic | D004347 drug interaction Q000008 administration & dosage Q000009 adverse effects Q000175 diagnosis Q000627 therapeutic use Q000628 therapy Q000744 contraindications |

38 subTopics | |||||

| informationRecipient | provider patient |

Provider | Health care provider Patient Registered Nurse |

Health care provider Patient Registered Nurse |

Health care provider Patient |

any | |

| InstitutionID | BWH MGH any |

UW | |||||

| Care Setting (same as encounter) | IMP Inpatient encounter AMB Ambulatory, EMER Emergency, FLD Field, HH Home health, VR virtual any |

any | any | any | any | any | any |

| UserRole | MD Medical Doctor any |

nurse pharmacist physician, any |

MD | Health care provider Registered Nurse |

Health care provider Registered Nurse |

Health care provider | any |

| AgeGroup | D007223 Infant; 1 to 23 months D007231 infant, newborn; birth to 1 month D002675 child, preschool; 2 to 5 years D002648 child; 6 to 12 years D000293 adolescent; 13–18 years D055815 young adult; 19–24 years D000328 adult; 19–44 years D008875 middle aged; 45–64 years D000368 aged; 56–79 years D000369 aged, 80 and older; a person 80 years of age and older |

any | D000368 aged; 56–79 years D000369 aged, 80 and older; a person 80 years of age and older any |

D007223 Infant; 1 to 23 months D007231 infant, newborn; birth to 1 month D002675 child, preschool; 2 to 5 years D002648 child; 6 to 12 years D000293 adolescent; 13–18 years any |

any | any | any |

| Gender | M, F | any | any | any | any | any | any |

Notes: Full table available at: http://www.dbmi.columbia.edu/~ciminoj/amia13/Appendix.xls

CSLs can also be selected by matching the clinical concept related to the infobutton call (sometimes referred to as the “concept of interest”; formally, the “mainSearchCriteria” or MSC) to some “domain of interest”. In most cases, the domain of interest was one that generally corresponded to the clinical task (e.g., laboratory tests for LABRREV, medications for MEDOE, diseases for DIAGLISTE, etc.). In some cases, the institution chose to restrict the domain of interest related to specific terms or classes of terms. For example, the University of Utah created a CSL to select the Genetics Home Reference for the clinical task DIAGLISTE, but restricted the MSC to be one of the genetic conditions covered by that resource. The Columbia IM supports a “semantic expansion” process whereby the initial MSC can generate the inclusion of additional concepts that can be used to match CSLs. For example, when the MSC is “serum calcium test”, the IM can add “calcium” and “hypercalcemia” to the list of terms. Information about the use of MSC to match specific domains is included in the online appendix.

Finally, a CSL can include a specification for a “subtopic”. This parameter is not used for resource selection but rather is included as a value to be passed to a resource if a user chooses that resource. For example, Intermountain provides links to the Cochrane Collection that are specific for therapy and diagnosis. The use of subtopics by the different IMs is shown in Table 3.

Discussion

This paper summarizes the experience of the institutions that have been the main developers of infobutton managers. The methods used to decide on which resources to include and how to customize their selection has been a combination of expert informationist and informatician opinion, empirical observational studies, log file transaction analysis and years of trial and error. While a review of all this work is beyond the scope of this paper, the results of all their experience is manifested by the actual CSLs that have been created, and the usage data that reflects actual user preferences. While the information needs and available resources will vary from institution to institution (in part, no doubt, because of inter-institutional variations in subscriptions and licenses), the degree of overlap among the institutions included in this paper suggests that the resources and CSL parameter settings shown in the tables and appendix can be a good starting point for those seeking to create CSLs for use with infobuttons in their own institutions.

Each institution will make its own decision about whether to integrate into their EHR links to single resources or links to an IM. If an IM is chosen, no matter which one it is, those charged with its configuration (the librarians) will be faced with the kinds of choices shown in Figure 1. While this might be accomplished with third-party IMs in a variety of ways, we can illustrate the process with one IM that is freely available to those institutions that choose to use it: OpenInfobutton (OI), which can be customized through the Librarian Infobutton Tailoring Environment (LITE).

The first task of the librarian is to select a clinical task that corresponds to a particular EHR function in which an information need is likely to arise. Once a task is selected, the librarian must select a resource. LITE provides users with a library of resource links that have already been represented for use with OI, so the selection process is simple. It is at this point that the librarian can refer to our Table 2 (or the online appendix) for suggestions about the resource or resources that others have used successfully in a similar situation.

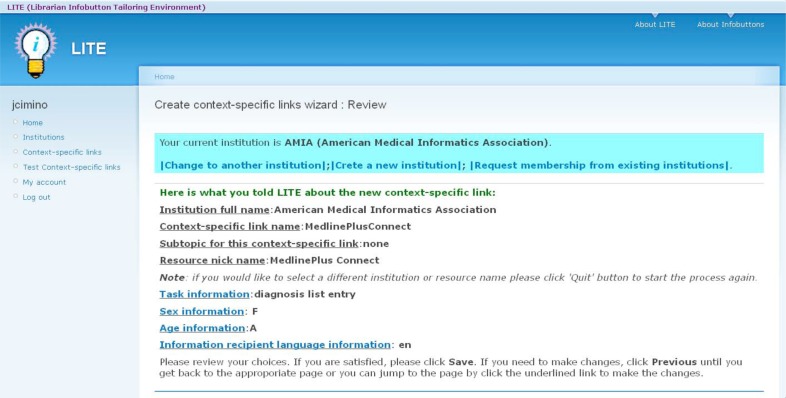

Once the resource is selected, LITE then guides the librarian through the process of selecting CSL parameters such as user role, patient age, etc. The librarian can use the examples in the online appendix to select parameter values, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2:

Creating a Context-Specific Link in LITE. The user is using LITE to configure OpenInfobutton for a fictitious EHR at the American Medical Informatics Association. The user has chosen to link the resource MedlinePlus Connect to the clinical task “diagnosis list entry”. By clicking on “Sex Information”, “Age Information” or “Information recipient language information”, the user can limit the selection criteria for this resource. In the screen shot, the user has indicated that MedlinePlus Connect should be selected when the EHR user is entering a diagnosis on a problem list and the patient is an adolescent, English-speaking female.

There are many additional steps required for successful integration of infobuttons into EHRs. Some are technical, such as the creation of the actual HL7-compliant links between the systems, which can be carried out by information systems personnel. However, the decisions about which resources to link to in which situation must be made by those who have an understanding of the institution’s users and their information needs. The combined experience accumulated through our years of work, boiled down to these tables and the online appendix, should serve as a reasonable “starter set” for institutions that are just beginning this process and will be valuable for those seeking to meet current EHR “meaningful use” requirements.

Conclusions

The availability of OpenInfobutton puts compliance with infobutton-related meaningful use requirements within reach of all EHRs, while the HL7 standard simplifies the technical requirements. However, neither the regulations nor the standard provide guidance on what resources to make available in a given clinical situation. While the information needs of clinicians and their patients will almost certainly vary somewhat from institution to institution, our experience with this customization should have at least some relevance and could be especially helpful to those institutions that do not have sufficient resources to carry out their own information-needs studies.

Acknowledgments

Drs. Cimino and Jing have been supported in part by intramural research funds from the NIH Clinical Center and the National Library of Medicine. Dr. Del Fiol has been supported by grant number K01HS018352 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). OpenInfobutton has been supported by a Greenfield Innovations grant from the Veterans Health Administration and internal funds from the Department of Biomedical Informatics at the University of Utah. Dr. Overby has been supported in part by the Columbia University Training in Biomedical Informatics Grant (NIH NLM T15 LM007079), the University of Washington Informatics research training grant (NIH NLM T15 LM07442), and the University of Washington Genome Training Grant (NIH NHGRI T32 HG000035).

References

- 1.Cimino JJ, Elhanan G, Zeng Q. Supporting infobuttons with terminological knowledge. In: Masys DR, editor. Proceedings of the 1997 AMIA Annual Fall Symposium. 1997. pp. 528–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Federal Register. 2012 Mar 7;77(45):13832–13885. Wednesday. (see page 13847). [Google Scholar]

- 3.HL7 Version 3 Standard: Context Aware Knowledge Retrieval (“Infobutton”), Release 1. 2010. http://www.hl7.org/implement/standards/product_brief.cfm?product_id=208.

- 4.Cimino JJ, Jing X, Del Fiol G. Meeting the electronic health record “meaningful use” criterion for the HL7 infobutton standard using OpenInfobutton and the Librarian Infobutton Tailoring Environment (LITE). In: Hersh WE, editor. Proceedings of the 2012 AMIA Annual Fall Symposium; 2012; 2012. pp. 112–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Del Fiol G, Huser V, Strasberg HR, Maviglia SM, Curtis C, Cimino JJ. Implementations of the HL7 Context-Aware Knowledge Retrieval (“Infobutton”) Standard: challenges, strengths, limitations, and uptake. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2012 Aug;45(4):726–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strasberg HR, Del Fiol G, Cimino JJ. Terminology challenges implementing the HL7 context-aware knowledge retrieval (‘Infobutton’) standard. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2013 Mar 1;20(2):218–23. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cogdill KW. Information needs and information seeking in primary care: a study of nurse practitioners. Journal of the Medical Library Association. 2003 Apr;91(2):203–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Westbrook J, Gosling AS, Coiera E. Do clinicians use online evidence to support patient care? a study of 55,000 clinicians. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2004 Mar-Apr;11(2):113–20. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coumou HCH, Meijman F. How do primary care physicians seek answers to clinical questions? a literature review. Journal of the Medical Library Association. 2006 Jan;94(1):55–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McKnight M. The information seeking of on-duty critical care nurses: evidence from participant observation and in-context interviews. Journal of the Medical Library Association. 2006 Apr;94(2):145–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Younger P. Internet-based information-seeking behaviour amongst doctors and nurses: a short review of the literature. Health Information Library Journal. 2010 Mar;27(1):2–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2010.00883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenbloom ST, Geissbuhler AJ, Dupont WD, Giuse DA, Talbert DA, Tierney WM, Plummer WD, Stead WW, Miller RA. Effect of CPOE user interface design on user-initiated access to educational and patient information during clinical care. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2005 Jul-Aug;12(4):458–73. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1627. Epub 2005 Mar 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Del Fiol G, Haug PJ. Infobuttons and classification models: a method for the automatic selection of on-line information resources to fulfill clinicians’ information needs. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2008 Aug;41(4):655–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Del Fiol G, Haug PJ. Classification models for the prediction of clinicians’ information needs. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2009 Feb;42(1):82–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.07.00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hunt S, Cimino JJ, Koziol DE. A comparison of clinicians’ access to online knowledge resources using two types of information retrieval applications in an academic hospital setting. Journal of the Medical Library Association. 2013 Jan;101(1):26–31. doi: 10.3163/1536-5050.101.1.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cimino JJ, Li J, Bakken S, Patel VL. Theoretical, empirical and practical approaches to resolving the unmet information needs of clinical information system users. In: Kohane IS, editor. Proceedings of the 2002 AMIA Annual Fall Symposium. 2002. pp. 170–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cimino JJ, Friedmann BE, Jackson KM, Li J, Pevzner J, Wrenn J. Redesign of the Columbia University Infobutton Manager. In: Masys DR, editor. Proceedings of the 1997 AMIA Annual Fall Symposium. 1997. pp. 135–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maviglia SM, Yoon CS, Bates DW, Kuperman G. KnowledgeLink: impact of context-sensitive information retrieval on clinicians’ information needs. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2006 Jan-Feb;13(1):67–73. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Del Fiol G, Rocha RA, Clayton PD. Infobuttons at Intermountain Healthcare: utilization and infrastructure. In: Bates DW, editor. Proceedings of the 2006 AMIA Annual Fall Symposium. 2006. pp. 180–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Overby C, Tarczy-Hornoch P, Kalet I, Thummel K, Smith J, Del Fiol G, Fenstermacher D, Devine E. Developing a prototype system for integrating pharmacogenomics findings into clinical practice. Journal of Personalized Medicone. 2012;2(4):241–256. doi: 10.3390/jpm2040241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cimino JJ. From data to knowledge through concept-oriented terminologies: experience with the Medical Entities Dictionary. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2000;7(3):288–297. doi: 10.1136/jamia.2000.0070288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.