Abstract

Neglected children’s acute hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis (HPA axis) reactivity in response to a laboratory visit was contrasted with that of a comparison group. The authors examined initial salivary cortisol response upon entering the laboratory and its trajectory following a set of tasks designed to elicit negative self-evaluation in 64 children (30 with a history of neglect and 34 demographically matched comparison children). Neglected, but not comparison, children showed higher initial cortisol responses. The cortisol response of both groups showed a decline from the sample taken at lab entry, with neglected children’s cortisol exhibiting steeper decline. The groups, however, did not differ in their mean cortisol levels at 20 and 35 min post-task. The results are interpreted in terms of the meaning of initial responses as a “baseline” and as evidence for neglected children’s heightened HPA-axis reactivity as either a reflection of differences in home levels or the consequence of stress/anxiety associated with arrival at the laboratory.

Keywords: neglected children, cortisol reactivity, anticipatory reactivity, sampling

Neglect, the most frequent form of childhood maltreatment (USDHHS, 2009), is associated with a wide range of negative outcomes. These include poor emotional and social adjustment, delinquency, and academic problems (Bennett, Sullivan, & Lewis, 2010; Chapple, Tyler, & Bersani, 2005). The physiological impact of neglect includes dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis (Bruce, Fisher, Pears, & Levine, 2008; De Bellis, 2005; Gunnar & Donzella, 2002). The HPA axis controls glucocorticoid secretions, including cortisol. In most people, cortisol increases in response to acute stress and then gradually returns to its normal diurnal pattern. Chronic exposure to stress, however, leads to dysregulation of the HPA axis, including hyperactivity of the HPA axis in children between 2 and 8 years (Letourneau et al., 2006). Chronically high cortisol impairs neuronal growth and dendritic connections, thereby likely impacting brain structure and function (Shonkoff, 2003; Gunnar, 2009). The HPA axis, therefore, is critical to the body’s adaptation to stress and is one mechanism linking both acute and chronic stress to poor physical and mental health (Boyce et al., 1995; Jessop & Turner-Cobb, 2007; Kaplow & Widom, 2007; Middlebrooks & Audage, 2008).

Chronic stress that produces elevated cortisol levels early in life, however, can eventually lead to the later development of hypocortisolism (Gunnar & Vazquez, 2001). Studies of institutionalized children and deprived animals, for example, show that extreme forms of neglectful caregiving are associated with hypocortisolism, which also may lead to poor mental and physical health (Feng et al., 2011; Gunnar & Quevedo, 2008; Heim, Ehlert, & Hellhammer, 2000). A transition from hypercortisolism to hypocortisolism, however, may depend on factors such as the age, the frequency, duration, and severity of stress, and the presence of internalizing symptoms (Bevans, Cerbone, & Overstreet, 2008; Gustafsson, Anckarsäter, Lichtenstein, Nelson, & Gustafsson, 2010; Tarullo & Gunnar, 2006). While the transition from hypercortisolism to hypocortisolism is thought to be due to increased sensitivity to cortisol through a negative feedback loop, the specific parameters related to the presumed transition are not yet well understood. There is only limited longitudinal work examining neglected children’s cortisol functioning as a result of exposure to stress, and none as yet published to our knowledge that examines both changes in acute stress responses and shifts in diurnal patterning over time in the same children over time. Also poorly understood are specific mechanisms that might help prevent dysregulated HPA axis functioning, regardless of its manifestation. While it is unclear whether a particular child with a history of neglect may be at risk of hypercortisolism or hypocortisolism, neglected children as a group may be at increased risk of both outcomes as a result of dysregulation of the HPA axis. The study of HPA axis dynamics following early neglect may offer clues as to how to prevent the toxic effects of chronic stress on children’s HPA axis and health. For example, intervention work suggests that children with dysregulated cortisol production will develop more normalized diurnal patterns in response to enriched and responsive environments (Fisher, Stoolmiller, Gunnar, & Burraston, 2007). Our cross-sectional study does not address the hypocortisolism/hypercortisolism shift. Rather, the idea that neglected children may show dysregulated HPA axis dynamics generally prompted our study.

Several approaches have been used to examine group differences in HPA axis dynamics. One is to examine diurnal cycling. Cortisol typically rises upon waking with a mid-morning peak, followed by a steady decline throughout the day, reaching its lowest levels prior to sleep onset. Young neglected and institutionalized children, who endured prolonged periods of neglectful care, have been found to show a hypocortisolism pattern characterized by lower cortisol in the morning and a flatter diurnal cycle (Gunnar & Quevedo, 2008). Thus, any acute stressors would operate in the context of an already altered diurnal system in these children. A second approach is to examine individual differences in peak or average reactivity following a challenge, whether naturalistic or experimental. Studies of children’s responses to inoculation and social conflict are some examples of the challenges studied (Granger, Weisz, McCracken, Ikeda, & Douglas, 1996). Studies of adolescents and adults with histories of early life traumas, including maltreatment using this approach, do suggest that such children have higher cortisol reactivity to acute challenges (Bruce, Davis, & Gunnar, 2002; Bruce et al., 2008; Cichetti & Rogosch, 2001; Weaver et al., 2004; Wismer Fries, Shirtcliff, & Pollak, 2008; Zhang et al., 2006).

Observing initial cortisol responses and their subsequent trajectory in young, chronically stressed children is especially challenging. It is important to understand the type of contexts that may exacerbate stress responses. Individuals’ and groups’ cortisol reactivity, peak response, and homeostatic recovery are variable and influenced by factors such as the chronicity of stress, level of social support, depression, and/or comorbid psychiatric disorders (Harkness, Stewart, & Wynne-Edwards, 2011; Rao, Hammen, & Poland, 2010). Several normative studies of younger children also have reported elevated prestress cortisol levels in the laboratory compared to in-home samples, suggesting that preschool and young school age children may be stressed by merely coming to the laboratory for testing (Kestler & Lewis, 2009; Klimes-Dougan, Hastings, Granger, Usher, & Zahn-Waxler, 2001; Lewis, Thomas, & Worobey, 1990; Walker, Walder, & Reynolds, 2001). Whether this pattern is age-dependent has not yet been established. Some investigators have resorted to collecting multiple baselines or allowing a 10-min acclimation period to avoid anticipatory elevations or to provide “truer” baseline estimates, methods that add cost and introduce additional variation across studies (Harkness et al., 2011; Rao et al., 2010). Whether neglected children, whose HPA axis is already likely to be dysregulated, will show heightened initial levels before the introduction of a specific acute stressor has not been previously considered. Given a heightened initial cortisol response, further increment to a subsequent acute stressor may be less likely. For example, receiving a second inoculation during a pediatric exam did not produce an additional rise in cortisol (Lewis & Ramsay, 1995). Rather, cortisol responses to the second inoculation were statistically equivalent to those in response to the first. The second inoculation thus resulted in stable, high levels of cortisol relative to a single inoculation. By extension, if coming to the laboratory itself elevates cortisol, neglected children may show heightened cortisol responses prior to the introduction of any other stressor and show no further increase thereafter.

However, if subsequent acute events were nonstressful, then cortisol decline might be expected following initially heightened cortisol levels. Such trajectories have been previously observed in children’s responses to novel events (Gunnar, Talge, & Herrera, 2009). The pattern of neglected children’s responses observed to subsequent tasks therefore will be informative as to whether additional demands on an initially elevated system sustain heightened reactivity or whether homeostatic processes are recruited as children adapt to the novel setting.

The nature of the acute stressor at any age is also important. Past studies have not always found a cortisol response to standard pediatric inoculation, a clear, physical stressor (Lewis & Ramasy, 2002; Stansbury & Gunnar, 1994). Although responses to psychological stressors have also been inconsistent, contexts involving social or self-evaluation and that are uncontrollable appear generally to elicit cortisol increases (Dickerson & Kemeny, 2004). Having multiple stressors of some duration may also make cortisol increases more likely (Harkness et al., 2011). Variants of the Trier Social Stress Test requiring children to give a speech evaluated by others and to do mental arithmetic have resulted in cortisol increases in 7-to 9-year-olds and adolescents, although some studies report no change (Gunnar et al., 2009). In a younger sample, increases were not seen (Gunnar et al., 2009), suggesting that this protocol may be less meaningful for younger children. On the other hand, self-evaluative tasks that elicit both verbal self-evaluation and self-evaluative emotions such as shame and embarrassment are feasible with young children and cortisol increases have been reported in young children who respond to task failure with these emotions, suggesting that these tasks may be useful for studying individual differences (Lewis & Ramasy, 2002). Consequently, we used a series of self-evaluative tasks previously shown to elicit both cortisol increases and negative self-evaluation and/or shame/embarrassment in diverse samples of young children to examine cortisol response as a function of neglect in our sample (Bennett, Sullivan, & Lewis, 2005; Lewis & Ramasy, 2002; Sullivan, Bennett, & Lewis, 2003). Although we expected to observe a cortisol stress response to these tasks in comparison children, even if we failed to do so, the trajectory of neglected and comparison children’s cortisol responses might still differ, given neglected children’s hypothesized initial heightened cortisol reactivity and poorly regulated HPA axis. In this case, observation of the neglected children’s responses over time relative to a comparison group would shed light on differences in children’s homeostatic responses in the absence of any further stress.

We examined the cortisol responses of school age neglected children and a nonneglected comparison group during a laboratory visit that included tasks designed to prime self-evaluations. There were two hypotheses: (1) We hypothesized that neglected children, due to their greater risk of HPA dysregulation (i.e., either hypercortisolism or hypocortisolism), would show higher initial cortisol response upon arrival compared to the nonneglected group; (2) Given a higher initial level of cortisol upon arrival for neglected children, we also hypothesized that their cortisol levels would remain high relative to the comparison children if the subsequent self-evaluative tasks stressed the children as expected. We expected that comparison children would show a typical cortisol stress response, that is, we expected a pattern of increased cortisol in response to the self-evaluative tasks, followed by subsequent recovery. Conversely, if the self-evaluative tasks were not stressful, we expected comparison children’s cortisol levels would remain stable, while neglected children’s might decline, as observed following young children’s anticipatory responses (Gunnar et al., 2009; Kestler & Lewis, 2009).

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 64 children (48% male), 6 to 9 years old at enrollment, participating in a larger longitudinal study of maltreatment outcomes in Philadelphia and Trenton, whose parents agreed to allow cortisol sampling. Acceptance rate for cortisol collection was approximately 94% of all those approached. Data from five additional children (three with neglect) were excluded as sufficient saliva was not obtained for assay of all three samples. All participating parents signed an institutional review board (IRB) approved informed consent for the main study and signed an additional consent for cortisol sampling. Children over age 7 marked an assent form, while younger children gave verbal assent. The staff was blind to children’s Child Protective Service (CPS) status.

Neglected status was determined via CPS records, using case record abstraction to obtain the number and timing of all neglect allegations. The allegations were for physical neglect and/or supervisory neglect. All children with case records still resided in the family home with their mothers. The majority had two or three allegations in their open record (M = 3.31; SD = 2.37; Mode = 2) at least one of which involved the target child, indicating that neglect was a relatively persistent problem in the target child’s family. We also screened the comparison children for unreported neglect using the Parent–Child Conflict Tactics scale (CTS-PC; Straus, Hamby, Finkelhor, Moore, & Runyan, 1998). This edition of the CTS-PC contains an optional 5-item subscale that can be used to screen parental neglect. The sub-scale significantly discriminated children with CPS allegations from those without a history in previously published work (Bennett, Sullivan, & Lewis, 2006). None of the mothers in the comparison group in the current sample endorsed any items on this scale. Thus, all comparison children met a dual criterion of having no CPS reports of maltreatment and their mothers did not endorse any of the neglect items on the screen.

Table 1 reports the demographic information for the neglected and comparison groups. Neglected and comparison children did not differ on gender, age, or other demographic characteristics (ps ≥ .10) with the exception that mothers of neglected children tended to be older. None of the demographic characteristics, including child age, was related to cortisol level.

Table 1.

Sample Demographics. Means and Standard Deviations or Percentage of Group

| N | Total 64 | Neglect 30 | Comparison 34 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age in years | 32.8 (7.9) | 36.20 (6.2) | 30.1 (5.56)* |

| Maternal employment (%) | 40 | 38 | 36 |

| Years of schooling | 12.1 (1.8) | 11.77 (1.4) | 12.4 (2.0) |

| Ethnicity: Minority (%) | 88 | 90 | 86 |

| Hispanic (%) | 12 | 9 | 14 |

| English major language (%) | 98 | 100 | 96 |

| Adult/child ratio in household | 0.33 (.68) | 0.21 (.04) | 0 .45 (.16) |

| Biological father in household (%) No current partner (%) | 26 49 | 30 54 | 31 44 |

| Receiving public assistance (%) | 76 | 78 | 74 |

| Neglect incidents in record | — | 3.40 (2.40) | None |

| Child Age (in months, SD) | 82.7 (11.4) | 83.8 (10.6) | 80.6 (13.0) |

| Gender (% male) | 48 | 52 | 44 |

Note.

Mothers of neglected and comparison children differed significantly, t63 = 3.13, p = .003.

Procedure

All participants provided saliva samples at the time of their regularly scheduled semiannual laboratory visit. A female examiner conducted the procedures, which have been shown to elicit self-evaluation as well as cortisol increases in nonclinical samples. Mothers received $15 for the families’ participation at this visit. The visit consisted of interaction with the examiner (Mother was not present.) and completing a series of four easy and four difficult tasks (puzzles, matching figures), which took approximately 25 min of a 2-hr long visit. Each task was timed separately. Four of the eight tasks were purposefully too difficult for the children to complete within the allotted time and were designed to elicit negative emotions and self-evaluative verbal and expressive behavior; therefore, they can be regarded as potential stressors. These tasks have been previously used in the literature to elicit self-evaluative behavior and emotion in young children and will be summarized briefly here (see Bennett et al., 2005; Lewis & Ramasy, 2002; Sullivan et al., 2003, for further details regarding the puzzles and matching games and their administration, the scoring proceudres, coding). The procedure was approved by the IRB with the following provisions: (1) the tasks were unlikely to be more stressful than children might encounter in a school day or other routine test setting; (2) nothing would be done or said to deliberately shame or embarrass children; (3) a fixed order of tasks, ending with a success experience in each set of four would be used so that each child experienced a final outcome that was positive; (4) during a final debriefing at the end of the visit the examiner would state that she was happy with the child’s work, and (5) we would provide appropriate follow-up should any child become excessively distressed by the procedure. Follow-up was never necessary. Parents were also informed about the procedure during the consent process and had the opportunity to opt out of the procedure, although none did.

The fixed task order was such that following an initial success with each task, children twice experienced back-to-back failures. We included some manipulation checks to assess whether the children responded on average to these tasks as previously reported. After each task, children’s self-evaluation was primed by a series of questions as a manipulation check (see Bennett et al., 2005; Lewis & Ramsay, 2002, for additional details). Following the failures, children typically responded that the failed tasks were hard, that they did not do so well, and that they felt less happy than following the success tasks. No differences between neglected and comparison children were observed in this regard. Subsequent independent coding of children’s emotional responses by trained coders who met the previously established reliability criteria (average κs = .73) indicated that 86% of the children showed either shame or embarrassment in response to the failures. No differences in these responses were observed as a function of neglect, indicating that the failed tasks elicited age-appropriate negative self-evaluations for both neglected and comparison children.

Time of day

Because it was not possible to schedule all children at the same time each day, children were divided into those who were seen before noon (AM group) and those who were seen after noon (PM group) since cortisol values are likely to be lower in the afternoon than in the morning. The percentage of children seen in the AM was 47% of the comparison group and 38% of the neglected group (z for difference in percentages = .72; n.s). There were no differences in either group on any of the demographic characteristics as a function of time of day.

Cortisol samples

Three samples were collected: an initial sample, taken 10 min after arriving at the laboratory; a second, taken 20 min after the completion of the last failed task; and a third, taken 15 min later. These sampling intervals are consistent with those frequently reported for children this age (Gunnar et al., 2009). The time of day each sample was obtained was recorded. In addition, the time the child had awakened that morning was reported by their mothers. The three samples were collected via cotton dental roll without stimulants, expressed into a test tube, and frozen immediately. Approximately, 1 cc of saliva was collected for each sample to allow for replicated assay. The samples were assayed by the University of Colorado, Denver Behavioral Immunology and Endocrinology Laboratory. Reported values were in ug/dl units. Standardized residual scores were created using wake time to predict their observed cortisol level at that time point. Thus, each child’s cortisol level adjusted for time elapsed between waking and laboratory arrival.

Results

The data were examined to address the two hypotheses in turn. First, to address whether children’s cortisol responses differed at the outset of the lab visit, we examined initial cortisol responses as a function of neglected status and time of day (AM vs. PM testing) using univariate analyses with planned contrasts. Second, to assess whether and how neglected children’s cortisol levels responded to the subsequent psychological challenge, we examined the trajectory of cortisol levels across all three samples. Preliminary analyses explored gender differences, but as no significant main effect or interactions with gender were observed, it was not considered further.

We analyzed these data using both the wake time-controlled raw values and log10-transformed values due to the large standard deviations in raw cortisol levels and unequal variances. Waking time was initially included as a covariate in the analysis of the log-transformed data, but was subsequently omitted as it was not significant and did not interact with any other factor. The pattern of significant effects was similar for both sets of analyses but as the log data met the homogeneity and spherictiy assumptions of the univariate analysis and multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA), we report only the results for the transformed data at length. Table 2 summarizes the observed means and standard deviations for the three cortisol samples as a function of neglect to facilitate comparison with studies reporting only untransformed data.

Table 2.

Means and Standard Deviations of Cortisol Responses (μg/dl) Observed Across Three Samples in Neglected and Comparison Children

| Initial sample | Sample 2 | Sample 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group (N) | |||

| Neglected (30) | .232 (.236)a,b | .120 (.090)b | .120 (.441) |

| Comparison (34) | .143 (.094)a,c | .141 (.173) | .115 (.139)c |

| Total | .184 (.179) | .131 (.140) | .147 (.218) |

Note. Main effects for Group and Sample are shown. Means sharing a common subscript differed statistically at p < .05 in both raw and transformed analyses. See text for description of the significant differences in linear trends between neglected and comparison children.

Initial differences

A Group (2) by Time of Day (AM/PM) analysis of variance tested the difference in initial cortisol response between the neglected and comparison groups. Neglected children had higher initial cortisol levels than the comparison children; F(1, 60) = 4.06, p = .04, η2 = .06; power = .56. The mean group difference was .19, SE = .09, t(63) = 2.12, p = .04.

Time of day was also significant in this analysis: F(1, 60) = 7.14, p < . 01, η2 = .10, power = .75. Children tested in the morning had higher initial values than those tested in the afternoon as expected; mean difference = 0.24, SE = .09, t(63) = 2.78, p < .01. There was no Group by Time interaction, however, indicating that neglected children’s greater initial response relative to the comparison children was unaffected by when they were tested.

Cortisol trajectories

Next, we considered the change in cortisol level after the introduction of the self-evaluative tasks. We used MANOVA with repeated measures to examine the trajectory of cortisol samples (initial sample, Sample 2, Sample 3) as a function of Neglect (yes/no) and Time of Day (AM, PM). Polynomial contrasts were used to follow up the main effect of sample allowing us to describe the trajectory of change for all the children. The Sample by Group polynomial contrast specifically tested the differences in slope as a function of Neglect.

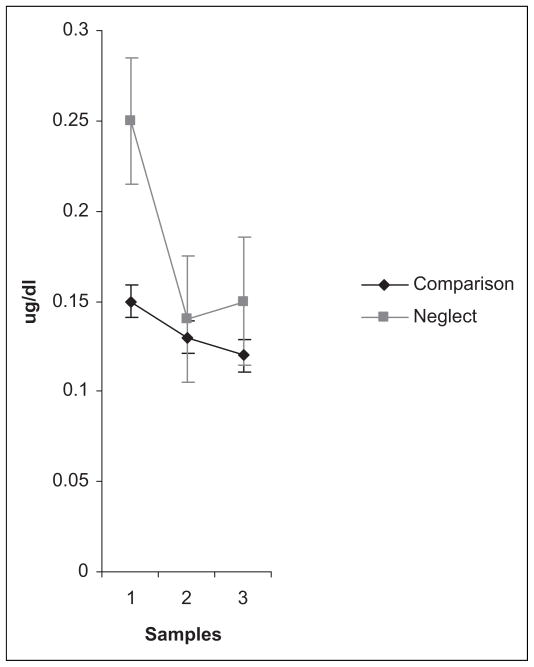

There was a main effect of Sample: F(1, 120) = 34.31, p < .001, η2 = .36, observed power = 1.00. Cortisol levels declined linearly from the initial to posttest samples; F(1, 60) = 48.67, p < .001, η2 = .45. However, this was qualified by a Group by Sample interaction: F(1, 120) = 34.31, p < .001, η2 = .36, observed power = 1.00. Figure 1, which plots the estimated marginal means across the three samples controlling for measurement error, depicts this interaction. Significant linear and quadratic contrasts indicated that the slope of cortisol decline differed by group; Flinear(1, 60) = 3.61, p < .01, η2 = .06, power = .49; Fquadratic(1, 60) = 8.30, p < .005, η2 = .12, power = .89. Neglected children’s cortisol levels declined steeply but leveled off, while comparison children’s cortisol levels showed a more modest but sustained decline across all three samples. Neglected children’s cortisol levels had declined significantly by the second sample, planned contrasts, F (1, 30) = 22.76, p < .001. In contrast, comparison children’s decline from the initial to the second sample was nonsignificant (p > .10). The main effect of Neglect was nonsignificant (p > .10) and there were no other significant interactions with Sample, and no interactions with Time of Day. A main effect for Time of Day was again observed in this analysis across all three samples. As previously reported for the initial sample, children tested in the morning had higher cortisol levels than those tested later in the day.

Figure 1.

Estimated marginal means of neglected and comparison children’s cortisol level across three samples. The first sample was obtained shortly after arrival at the laboratory. The second and third samples were obtained 20 and 35 min later following a series of tasks designed to elicit self-evaluative emotion.

Discussion

This study addresses two themes in the cortisol literature related to neglect. First, that neglected children’s HPA axis dysfunction might predispose them to show greater initial “baseline” cortisol levels upon coming to a laboratory visit and second, that challenge tasks with a self-evaluative component might show a typical cortisol stress response for comparison children at this age, but neglected children would not. Our first hypothesis was supported and is consistent for the most part with previous findings on heightened cortisol responses in other chronically stressed populations. We observed greater cortisol in neglected children’s initial samples in contrast to comparison children. Although cortisol levels are typically greater in the morning hours, initial stress reactions were not dependent on the time of day. Our findings are consistent with studies suggesting that greater and more prolonged cortisol elevations occur among youth with a history of early life adversity including maltreatment (Harkness et al., 2011; Rao et al., 2010). In these studies of adolescents, however, depression severity and concurrent self-reports of chronic life stress were important factors in this response, potential moderators not considered in our study due to the age of our participants. As noted in Table 1, the average age of our sample was a little over seven, below the recommended earliest age for the administration of self-reports such as the Children’s Depression Inventory.

Two other factors might contribute to the elevated initial levels of cortisol among neglected children. Elevated initial levels may reflect an anticipatory stress response to coming to the laboratory or might reflect differences in stress experienced immediately prior to the lab visit. Neglected children’s higher initial cortisol responses in this study were suggestive of an anticipatory stress response. Young children may show greater prestress lab “baseline” values compared to in-home samples (Kestler & Lewis, 2009). However, we cannot confirm anticipatory stress responses without home data for comparison. Although coming to our lab was unlikely to be as anxiety producing as an imminent pediatric office visit, the stressor in the Kestler and Lewis (2009) study, collection of a home baseline in future studies would help confirm that these responses reflect anticipatory stress. Alternatively, the hypothesis that neglected children experienced greater stress for reasons other than anticipatory anxiety may be more in keeping with our understanding of the psychological aspects of neglect. Separation paradigms have shown that adult attention and supportiveness provides a potent buffer against stress for children (Gunnar & Donzella, 2002). Neglectful parents by definition are less responsive and attentive to their children’s needs (Glaser, 2002). Our finding thus supports the idea that neglected children had mothers who may have differed in the support provided to their children immediately prior to the lab visit. Although we did not measure this variable, future work might consider assessing parent supportiveness, child stress, and perhaps even parental stress and cortisol levels around organizing children to come to the lab or taping parent–child verbal exchanges during the trip to the lab for coding of verbal indicators of parental supportiveness and child stress.

Our second hypothesis concerned the trajectory of cortisol responses over time. We initially expected that nonneglected children would show a typical poststress elevation. This hypothesis was not confirmed. While the comparison children as a group did not show a stress response, the neglected children’s responses followed a similar trajectory that also suggested the lack of a stress response. However, the slope of decline differed. Although both groups of children showed declines in cortisol from the initial sample through posttask samples, neglected children’s cortisol declined rapidly, with subsequent leveling off, whereas comparison children’s cortisol declined more gradually. By the second and third samples, neglected and comparison children’s cortisol levels no longer differed statistically. That is, although both groups of children can be said to have acclimated to the laboratory visit, the neglected children’s cortisol showed a greater decrease, likely due to their higher initial responses. Whether the final levels of cortisol observed in either group represent a return to prelaboratory levels cannot be addressed, although presumably the declines in both groups represent a return to a more typical diurnal level. In examining neglected children’s responses, it seems important to collect a home baseline sample either prior to laboratory testing or at a comparable time of day when their acute responses to a potential stressor are of interest.

Although our self-evaluative challenge tasks did not elicit a stress response as measured by cortisol, in retrospect a number of factors may have contributed to this null finding. The tasks used in this study may not have been sufficiently stressful to elicit a stress response. The self-evaluative features of our task have been demonstrated for young children (Bennett et al., 2005), however, the levels of embarrassment or shame associated with cortisol rises may have been too mild or fleeting in this study to activate the HPA axis. In addition, the interspersed successes in the task series may have blunted the overall stressfulness of the procedure. This raises the possibility that providing success experiences to children may be an effective intervention, buffering the adverse effects of stress in early childhood.

Prior studies are fairly consistent in sampling children’s saliva 20–35 min post-stressor across a wide age range, so it is unlikely that cortisol peaked outside of the times that we sampled following the failure tasks. Harkness, Stewart, and Wynne-Edwards (2011) found adolescents’ cortisol peaked 25–30 min after the onset of a stressor (being told they were to prepare a speech), rather than in direct response to the evaluation itself. While this point represented the highest level of all their samples, the next sample was not collected until about 55 min poststressor in their study. It is not possible therefore to state that this was the peak response, or that the anticipatory threat of having to give a speech was worse than actually giving it.

If the self-evaluative challenge was not a stressor for either group in the current study, then the observed declining cortisol trajectories of both groups is interpretable in light of data on young children’s cortisol response to novel contexts and their potential stressful nature. Of the six studies examining “novel event stressors” reviewed by Gunnar, Talge, and Herrera (2009, p. 959, table 7), four elicited decreases in cortisol while two found no differences, suggesting the results presented here are typical. Our findings also converge with Rao et al. (2008), who obtained five prestress samples in youth. Focusing on their nondepressed group, initial cortisol levels declined across the prestress measures. Similarly, children exhibited decreased cortisol levels over four cognitive tasks requiring attention (Davis, Bruce, & Gunnar, 2002). Thus, novel settings with attentional demands seem to be associated with the decreased cortisol pattern over time as observed in this study. Regardless of group differences, both neglected and comparison children’s cortisol levels in this study may have decreased because they spent time interacting with a novel, but friendly staff member, and so were able to acclimate to the lab. In this sense, cortisol elevations upon coming to the lab may represent behavioral inhibition or wariness to novelty. The lab visit, a novel setting in which strangers are encountered, may be more stressful to some children due to this novelty and their own heightened sensitivity to context. Hence, anticipating and initiating the lab visit may have been more stressful than the subsequent self-challenging tasks the children encountered. To test this hypothesis directly poses significant methodological challenges. Our findings plus the concept of anticipatory stress advanced by Kestler and Lewis (2009) do suggest, however, that a context by child interaction should be considered. Neglected children might be especially prone to showing higher initial cortisol in response to new, unknown contexts due to the often chronic and chaotic nature of maltreating environments which they typically experience. In this sense, a cortisol rise in response to a new context may have promoted heightened vigilance, perhaps a coping mechanism for these children. However, the long-term implications of this response pattern and whether it can be altered as children mature remain important research questions.

Subsequent declines in cortisol once children perceived that the environment to nonthreatening support the view that down-regulation of neglected children’s cortisol responses is possible. Why was the decline in neglected children’s cortisol response stronger than for the comparison group? One answer is that neglected children’s dysregulated HPA axis may simply be more volatile and subject to greater swings. Other answers rest on the quality of intervening stimuli in helping children to overcome stress in response to a new setting. We have already mentioned the role that a friendly, nonthreatening social experience might play. Alternatively, mild challenges such as employed here may actually have exerted an organizing influence on the neglected children’s HPA axis functioning. As they acclimated to the laboratory context, focusing on a task may have exerted a calming influence, helping to dampen their reactivity. The pediatric psychology literature shows the positive effects of using “distraction” techniques for children who are undergoing stressful medical procedures (Uman, Chambers, McGrath, & Kisely, 2008), providing evidence that external regulatory support can successfully calm children. Furthermore, neglected children in a foster care program developed more normal morning and evening cortisol levels over a 12-month preschool intervention, whereas a comparable group of neglected children in regular foster care placements did not (Bruce et al., 2008; Fisher et al., 2007). This suggests an engaging, stable, and predictable environment may be important in promoting HPA axis regulation. Likewise, it is possible to lower cortisol below home baseline levels, although the mechanisms responsible for this remain unclear (Gunnar & Donzella, 2002). Nonetheless, it appears that engaging, positive, developmentally appropriate activities can act to improve diurnal cortisol regulation. The current study also suggests that age-appropriate performance tasks (matching games and puzzles) may promote acclimation to a novel setting, acting as an effective anxiety reducer for young children. Another implication is that children whose heightened cortisol levels fail to dampen despite opportunities to acclimate may be the most severely dysregulated and therefore at risk.

In summary, neglected children were more likely to exhibit a heightened initial cortisol stress response upon coming to a laboratory. On a positive note, acclimation was observed among neglected children and, ultimately, cortisol levels were not different from those observed in the comparison children. Helping neglected children to manage their acute stress reactivity (whether through distraction techniques, relaxation techniques, or use of self-statements) might be important for improving their stress regulation.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank professor Douglas Ramsay of UMDNJ (retired) for assistance with preliminary analyses, Lola Clarke for exceptional professional dedication as family coordinator, and the research teams at RWJMS and DUCOM for data collection and preparation. The authors acknowledge the cooperation of the Department of Human Services (Philadelphia) and the Division of Youth and Family Services (New Jersey State Department of Children and Families) for assistance with screening participants.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by federal grants MH064473 and DA1153/ MH56751 (Michael Lewis, P.I.).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Reprints and permission: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

References

- Bennett DS, Sullivan MW, Lewis M. Young children’s emotional-behavioral adjustment as a function of maltreatment, shame, and anger. Child Maltreatment. 2005;10:311–324. doi: 10.1177/1077559505278619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DS, Sullivan MW, Lewis M. Relations of parental report and observation of parenting to maltreatment history. Child Maltreatment. 2006;11:63–75. doi: 10.1177/1077559505283589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DS, Sullivan MW, Lewis M. Neglected Children, shame-proneness, and depressive symptoms. Child Maltreatment. 2010;15:305–314. doi: 10.1177/1077559510379634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevans K, Cerbone A, Overstreet S. Relations between recurrent trauma exposure and recent life stress and salivary cortisol among children. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20:257–272. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce WT, Chesney M, Alkon A, Tschann JM, Adams S, Chesterman B, Wara D. Psychobiologic reactivity to stress and childhood respiratory illnesses: Results of two prospective studies. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1995;57:411–422. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199509000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce J, Davis EP, Gunnar MR. Individual differences in children’s cortisol response to the beginning of a new school year. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2002;27:635–650. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(01)00031-2. PII s0306-4530(01)00031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce J, Fisher PA, Pears KD, Levine S. Morning corisol levels in pre-school aged foster children: Differential effects of maltreatment type. Developmental Psychobiology. 2008;51:14–23. doi: 10.1002/dev.20333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapple CL, Tyler KA, Bersani BE. Child neglect and adolescent violence: Examining the effects of self-control and peer rejection. Violence and Victims. 2005;20:39–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cichetti D, Rogosch FA. The impact of child maltreatment and psychopathology on neuroendocrine functioning. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:783–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis EP, Bruce J, Gunnar MR. The anterior attention network: Associations with temperament and neuroendocrine activity in 6-year-old children. Developmental Psychobiology. 2002;40:43–56. doi: 10.1002/dev.10012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bellis MD. The psychobiology of neglect. Child Maltreatment. 2005;10:150–172. doi: 10.1177/1077559505275116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson SS, Kemeny ME. Acute stressors and cortisol responses: a theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research. Psychol Bull. 2004;130(3):355–391. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X, Wang L, Yang S, Qin D, Wang J, Li C, Li L, Ma Y, Hu X. Maternal separation produces lasting changes in cortisol and behavior in rhesus monkeys. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011;108(34):14312–14317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019934108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics. America’s Children: Key National Indicators of Well-Being, 2011. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PA, Stoolmiller M, Gunnar MR, Burraston BO. Effects of a therapeutic intervention for foster preschoolers on diurnal cortisol activity. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32:892–905. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser D. Emotional abuse and neglect (psychological maltreatment): A conceptual framework. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2002;22:697–714. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00342-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granger DA, Weisz JR, McCracken JT, Ikeda SC, Douglas P. Reciprocal influences among adrenocortical activation, psychosocial processes, and the behavioral adjustment of clinic-referred children [Fall 2009] Child Development. 1996;67:3250–3262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar MR, Vazquez DM. Low cortisol and a flattening of expected daytime rhythm: potential indices of risk in human development. Dev Psychopathol. 2001;13(3):515–538. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401003066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar MR, Donzella B. Social regulation of the cortisol levels in early human development. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2002;27:199–220. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(01)00045-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar MR, Quevedo KM. Early care experiences and HPA axis regulation in children: a mechanism for later trauma vulnerability. Stress Hormones and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder: Basic Studies and Clinical Perspectives. 2008;167:137–155. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)67010-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar MR, Talge NM, Herrera A. What does and does not work in producting mean differences in salivary cortisol. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;27:199–220. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson PE, Anckarsäter H, Lichtenstein P, Nelson N, Gustafsson PA. Does quantity have a quality all its own? Cumulative adversity and up- and down-regulation of circadian salivary cortisol levels in healthy children. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35:1410–1415. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkness KL, Stewart JG, Wynne-Edwards KEK. Cortisol reactivity to social stress in adolescents: Role of depression severity and child maltreatment. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36:173–181. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C, Ehlert U, Hellhammer DH. The potential role of hypocortisolism in the pathophysiology of stress-related bodily disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2000;25(1):1–35. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(99)00035-9. S0306-4530(99)00035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessop DS, Turner-Cobb JM. Measurement and meaning of salivary cortisol: A focus on health and disease in children. Stress. 2007;2007:1–14. doi: 10.1080/10253890701365527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplow JB, Widom CA. Age of maltreatment predicts long-term mental health outcomes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:176–187. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kestler L, Lewis M. Cortisol responses to inoculation in 4-year-old children. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:734–751. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimes-Dougan B, Hastings PD, Granger DA, Usher BA, Zahn-Waxler C. Adrempcprtoca; actovotu om at-risk and normally developing adolescents: Individual differences in salivary cortisol basal levels, diurnal variation, and response to social challenges. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:695–719. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401003157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letourneau NL, Fedick CB, Willms JD, Dennis CL, Hegadoren K, Stewart JG. Longitudinal study of postpartum depression, maternal-child relationships and children’s behavior to 8 years of age. In: Devroe D, editor. Parent-child relations: New research. New York, NY: Nova Science; 2006. pp. 45–63. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M, Ramsay D. Stability and change in cortisol and behavioral responses to stress during the first 18 months of life. Developmental Psychobiology. 1995;28:419–428. doi: 10.1002/dev.420280804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M, Ramasy D. Cortisol responses to embarrassment and shame. Child Development. 2002;70:1034–1045. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M, Thomas D, Worobey J. Developmental organization, stress and illness. Psychological Science. 1990;1:316–318. [Google Scholar]

- Middlebrooks JS, Audage NC. The effects of childhood stress on health across the lifespan. Washington, DC: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rao U, Hammen C, Ortiz LR, Chen LA, Poland RE. Effects of early and recent adverse experiences on adrenal response to psychosocial stress in depressed adolescents. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64(6):521–526. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.05.012. S0006-3223(08)00643-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao U, Hammen CL, Poland RE. Longitudinal course of adolescent depression: neuroendocrine and psychosocial predictors [for Court revision, 2011] Journal of the American Academy of Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49:141–151. doi: 10.1097/00004583-201002000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff J. From neurons to neighbors: Old new challenges for developmental and behavioral pediatrics. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2006;24(1):70–76. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200302000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stansbury K, Gunnar MR. Adrenocortical activity and emotion regulation. In: Fox N, editor. The development of emotion regulation: Biological and behavioral considerations. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. Vol. 59. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1994. pp. 108–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Finkelhor D, Moore DW, Runyan D. Identification of child maltreatment with the Parent-Child conflict tactics scales: Development and psychometric data for a national sample of American parents. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1998;22:249–270. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00174-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan MW, Bennett DS, Lewis M. Darwin’s view: Self-evaluative emotions as context-specific emotions. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2003;1000:304–308. doi: 10.1196/annals.1280.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarullo AR, Gunnar MR. Child maltreatment and the developing HPA axis. Hormones and Behavior. 2006;50:632–639. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uman LS, Chambers CT, McGrath PJ, Kisely S. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials examining psychological interventions for needle-related procedural pain and distress in children and adolescents: An abbreviated Cochrane review. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2008;33:842–854. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker EF, Walder DJ, Reynolds F. Developmental changes in cortisol secretion in normal and at-risk youth. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:721–732. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401003169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver IC, Cervoni N, Champagne FA, D’Alessio AC, Sharma S, Seckl JR, Dymov S, Szyf M, Meaney MJ. Epigenetic programming by maternal behavior. Nature Neuroscience. 2004;7:847–854. doi: 10.1038/nn1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wismer Fries AB, Shirtcliff EA, Pollak SD. Neuroendocrine dysregulation following early social deprivation in children. Developmental Psychobiology. 2008;50:588–599. doi: 10.1002/dev.20319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang TY, Bagot R, Parent C, Nesbitt C, Bredy TW, Caldji C, Meaney MJ. Maternal programming of defensive responses through sustained effects on gene expression. Biological Psychology. 2006;73:72–89. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]