Abstract

Objective To perform a systematic review of studies that assessed the potential of patient decision support interventions (decision aids) to generate savings.

Design Systematic review.

Data sources After registration with PROSPERO, we searched 12 databases, from inception to 15 March 2013, using relevant MeSH terms and text words. Included studies were assessed with Cochrane’s risk of bias method and Drummond’s quality checklist for economic studies. Per patient costs and projected savings associated with introducing patient decision support interventions were calculated, as well as absolute changes in treatment rates after implementation.

Eligibility criteria Studies were included if they contained quantitative economic data, including savings, spending, costs, cost effectiveness analysis, cost benefit analysis, or resource utilization. We excluded studies that lacked quantitative data on savings, costs, monetary value, and/or resource utilization.

Results After reviewing 1508 citations, we included seven studies with eight analyses. Of these seven studies, four analyses predicted system-wide savings, with two analyses from the same study. The predicted savings range from $8 (£5, €6) to $3068 (£1868, €2243) per patient. Larger savings accompanied reductions in treatment utilization rates. The impact on utilization rates was mixed. Authors used heterogeneous methods to allocate costs and calculate savings. Quality scores were low to moderate (median 4.5, range 0-8 out of 10), and risk of bias across the studies was moderate to high (3.5, range 3-6 out of 6), with studies predicting the most savings having the highest risk of bias. The range of issues identified in the studies included the relative absence of sensitivity analyses, the absence of incremental cost effectiveness ratios, and short time periods.

Conclusion Although there is evidence to show that patients choose more conservative approaches when they become better informed, there is insufficient evidence, as yet, to be confident that the implementation of patient decision support interventions leads to system-wide savings. Further work—with sensitivity analyses, longer time horizons, and more contexts—is required to avoid premature or unrealistic expectations that could jeopardize implementation and lead to the loss of already proved benefits.

Registration PROSPERO registration CRD42012003421.

Introduction

There has been increasing interest in implementing patient decision support interventions. They definitely help inform decisions, and patients tend to opt for more conservative treatment choices.1 Evidence from randomized trials shows that these interventions increase patients’ knowledge, produce more accurate expectations, and lead to treatment choices that are more congruent with patients’ informed preferences.1 There is, in short, an ethical imperative to support their use in practice.2 There have also been claims that they have the capacity to generate healthcare savings,3 4 but these are less well substantiated, although prominent in many commentaries.

This combination of known benefits and potential savings has led to prominence in healthcare policy: shared decision making and the use of decision support interventions for patients are cited as promising developments in the Affordable Care Act (ACA). In the United Kingdom, the Advancing Quality Alliance (AQuA) claimed that the use of such decision support interventions could lead to “potential savings to the NHS [National Health Service]. . .”5 In addition NHS England has taken responsibility for the implementation of shared decision making in NHS care since April 2013.6 One of their key messages for commissioners was that “given informed choice, many patients choose less radical treatment, which may result in savings.”6 In 2010, NHS Direct claimed that patient decision support interventions would save the NHS money by ensuring “more efficient use of resources.”7

Estimated savings from the implementation of patient decision support interventions have attracted considerable attention. In 2008, the Lewin Group in the United States estimated savings to Medicare of $9bn (£5.5bn, €6.6bn) if they were implemented for 11 common healthcare procedures.8 A report from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) in 2013 claimed “significant reductions in surgery rates and overall health care costs.”9 A 2009 systematic review of the impact of patient decision support interventions examined 86 published randomized trials and summarized the evidence by saying that these interventions lead to patients choosing less “discretionary” surgery but that the effects on costs and resource use were inconclusive.1

The evidence that these tools act to inform and enable patients to determine the likelihood of benefit versus harm is clear and well proved.1 The same review is cautious about their impact on cost.1 We performed a detailed systematic review of a wide range of studies to assess the potential of patient decision support interventions to generate savings, given that premature or unrealistic expectations could jeopardize wider implementation and lead to the loss of the already proved benefits.

Methods

To be eligible for inclusion, we considered studies that evaluated interventions designed to “help people make specific and deliberative choices among options (including the status quo) by providing (at the minimum) information on the options and outcomes relevant to a person’s health status and implicit methods to clarify values.” We considered all primary peer reviewed studies, including randomized controlled trials and economic evaluations as well as experimental and quasi-experimental designs utilizing a comparison group. We excluded studies that lacked quantitative data on savings, costs, monetary value, and/or resource utilization.

We searched databases from their inception to 15 March 2013 using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and keywords in three domains: patient decision support intervention/decision aid; patient; and cost. Databases included Medline, CINAHL, Cochrane Central, Campbell Collaboration, Embase, Business Source Complete, EconLit, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination: NHS Economic Evaluations Database (NHS EED), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) and Health Technology Assessment (HTA), and Web of Science. We also checked bibliographies of included studies for relevant studies.

The electronic search strategy we used for Medline is provided in appendix table A. Strategies used for other databases are available on request. Titles and abstracts were screened by one researcher (TW), 10% were screened by a second (PJB), and disagreements were resolved by discussion. After piloting the process, two researchers (TW, PJB) used a standardized data extraction process.10

The Center for Reviews and Dissemination and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) recommend the use of checklists to appraise study quality.11 Three researchers (TW, PJB, CO’N) assessed the quality of economic evaluations in the included studies using Drummond’s 10 item checklist; items were recorded as being present or absent (score=1 or 0).10 12 Two researchers (TW and PJB) assessed risk of bias using Cochrane’s six item checklist; items were recorded as low risk (score=0), indeterminate or high risk (score=1).13 Disagreements were resolved by discussion.

For each study, we examined the savings or additional spending that followed implementation of patient decision support interventions, the costs associated with delivering such interventions, and rates of treatment utilization in both the control and intervention groups. Because savings are purported to be associated with changes in treatment utilization, we calculated absolute differences in utilization after the implementation of decision support interventions and projected a potential impact on utilization rates per 100 patients exposed. Currency data were converted to US dollars on June 15 of the article’s publication year. Where studies had more than one decision support intervention group, we extracted data that enabled the most accurate estimates of the impact of delivering a decision support interventions alone.

Results

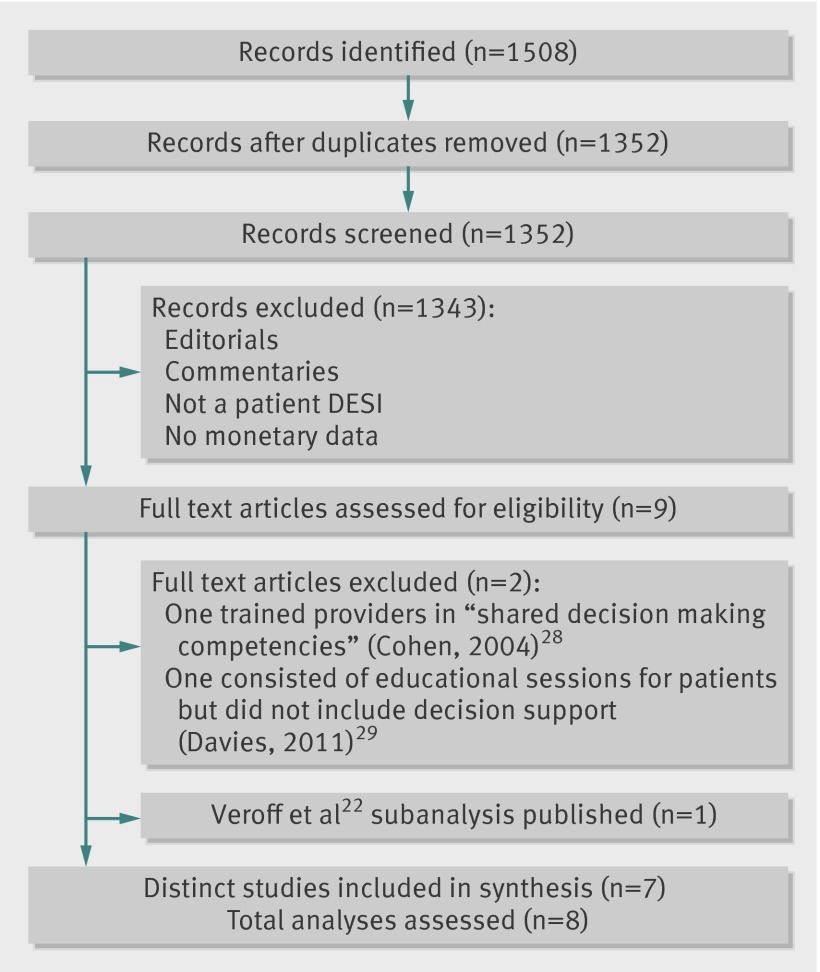

The initial search yielded 1508 records, with 1352 remaining after we removed duplicates. Inter-rater reliability during the screening process, assessed with Cohen’s κ, was substantial (>0.7), as defined by Landis and Koch.14 Nine papers proceeded to full text review. During full review, it became apparent that two of these nine papers were not studies of patient decision support interventions, leaving seven studies. In total, seven studies with eight analyses moved to appraisal and data extraction (figure).15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22

Study selection process

Six studies were randomized trials in outpatient settings; three from the UK and one each from the Netherlands, Finland, and the US.16 17 18 19 20 21 One study, from the US, utilized a pre-post observational design,15 and one paper was a subanalysis of a previously reported randomized controlled trial22 (table 1). Sample sizes ranged from 112 to 60 185 patients. There were differences in the methods utilized to deliver decision support interventions: two studies mailed the interventions to patients and two studies mailed the interventions to patients then followed up with face-to-face interviews when the patient arrived at the clinic. Two studies used interactive videodiscs throughout to deliver decision support; the authors noted CD-ROMs and internet technology became available near the conclusion of the trials and these changes would have decreased resource requirements.17 18 The study by Wennberg and Marr21 and the subsequent subanalysis by Veroff and colleagues22 used health coaches to contact eligible individuals by phone to discuss their diagnoses, review care instructions, provide motivation for recommended behavioral changes, and offer decision support. The Wennberg and Marr study did a comparison between different levels of outreach consisting of three attempted telephone coaching interactions in one arm versus an enhanced care arm consisting of five attempted interactions—that is, there was no group that did not receive decision support.21

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in review of patient decision support interventions (DESI)

| Study | Population | Sample Size | Assessed impact of DESI on | Study design | Mode of delivery | Additional concurrent interventions | Risk of bias* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arterburn (2012), US | Patients with hip osteoarthritis | 1788 | Treatment choices | Before-after observation | DVD and booklets; online | Provider education. Feedback to providers on surgery rates. Larger initiative to implement shared decision making across entire organization. Washington state legislation prompting greater use DESI during informed consent process. Medical home initiative in primary care | 6 |

| Patients with knee osteoarthritis | 7727 | ||||||

| Kennedy (2002), UK | Women with menorrhagia | 894 | Treatment choices, health outcomes, and spending | 3 arm RCT | Videotape and booklets | No additional interventions† | 3 |

| Murray (2001a), UK | Men with benign prostatic hypertrophy | 112 | Treatment choices, health outcomes, resource use, and spending | RCT | Interactive multimedia video with booklet | No additional interventions | 3 |

| Murray (2001b), UK | Peri-menopausal women | 205 | Treatment choices, health outcomes, and spending | RCT | Interactive multimedia video with booklet | No additional interventions | 3 |

| Van Peperstraten (2010), Netherlands | Couples on waiting list for in vitro fertilization treatment | 308 | Single embryo transfer use and spending | RCT | Booklet and in person interview | Reimbursement offer for additional treatment cycle if single embryo transfer selected but unsuccessful. In person discussion of DESI content and reimbursement offer with nurse. Telephone call from nurse to answer additional questions | 4 |

| Vuorma (2004), Finland | Women with menorrhagia | 363 | Treatment choices, health outcomes, and spending | RCT | Booklet | No additional interventions | 3 |

| Wennberg (2010), US | Patients with preference sensitive conditions | 18 351 | Monthly medical and pharmacy spending, hospital admissions | RCT | Telephone calls from health coaches, booklets, and videos | Education , behavioral change, and motivational counseling | 4 |

| Veroff (2013), US | Subanalysis of data from Wennberg (2010) | 60 185 | 5 |

*Possible range 0-6, with higher scores indicated greater risk of bias.

†In third trial arm, DESI was delivered in combination with structured interview to clarify and elicit patient preferences.

Four of the eight analyses reported significant savings after the introduction of patient decision support interventions; savings ranged from $8 to $3068 per patient.15 16 21 22 The remaining analyses did not find significant savings (table 2). We describe these four studies below.

Table 2.

Economic analyses in review of patient decision support interventions (DESI)

| Study | Treatment | Treatment rate | Relative rate (95% CI) | Absolute difference | Perspective | Time horizon | Per patient costs to implement DESI* | Per patient savings* | Quality† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparison group | DESI | |||||||||

| Arterburn (2012) | Total hip replacement | 0.46 | 0.34 | 0.75 (0.64 to 0.89)‡ | 0.12 | Organization | 6 months | None reported | $3068 | 0 |

| Total knee replacement | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.59 (0.51 to 0.67)§ | 0.07 | $1999 | |||||

| Kennedy (2002)¶ | Hysterectomy | 0.41 | 0.44 | 1.05 (0.85 to 1.30) | −0.02 | Healthcare system | 2 years | $21 | $725 | 6 |

| Murray (2001a) | Prostatectomy | 0.02 | 0.11 | 5.05 (0.63 to 40.52) | −0.08 | Healthcare system | 9 months | $400 | −$517** | 5 |

| Murray (2001b) | Hormone replacement therapy | 0.36 | 0.41 | 1.16 (0.80 to 1.69) | −0.06 | Healthcare system | 9 months | $304 | −$303** | 4 |

| Van Peperstraten (2010) | Single embryo transfer | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.92 (0.69 to 1.23) | 0.02 | Healthcare system | Not clear | $145 | $219 | 8 |

| Vuorma (2004) | Hysterectomy | 0.48 | 0.51 | 1.05 (0.84 to 1.31) | −0.02 | Societal | 1 year | $10 | $409 | 3 |

| Wennberg (2010) | Surgical care†† | 0.13‡‡ | 0.12 | 0.93 (NR)§§ | 0.009 | Payer | 1 year | $2/month | $7.96 | 7 |

| Veroff (2013) | Subanalysis of data from Wennberg (2010) | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.87 (NR)¶¶ | 0.02 | Payer | 1 year | <$5/month | $23.27 | 6 |

*Currency converted to US dollars based on rates at June 15 of publication year and rounded to nearest dollar.

†Possible range 0-10 with higher scores indicating higher quality.

‡Including only those in DESI Group that were provided with DESI (41%), (adjusted) relative rate was 1.44 (1.08 to 1.93).

¶For group receiving DESI in combination with structured interview, absolute difference was 0.09 (0.01 to 0.17), relative rate was 0.78 (0.62 to 0.99), and per patient savings were $1184.

§Including only those in DESI group that were provided with DESI (28%), (adjusted) relative rate was 2.03 (1.58 to 2.61).

**Negative savings represent increases in spending.

††For heart, uterine, prostate, hip, knee, and back conditions.

‡‡Not typical control group. Usual care group received decision support.

§§P=0.28.

¶¶P<0.001.

Kennedy and colleagues reported significant potential savings for the UK healthcare system of $725 per patient after implementation of decision support intervention for women with menorrhagia.16 The authors calculate a total cost per patient of $21 to deliver the decision support intervention, which included the cost of the booklet, videotape, and 20 minutes of nursing time. They calculated the fixed intervention costs, however, by using a hypothetical scenario that involved projecting the use of the decision support intervention to all women in England and Wales aged 25-52 with uncomplicated menorrhagia.16 There was no significant difference in the rate of hysterectomies between the groups.

Arterburn and colleagues reported on a pre-post study that found per patient savings to the healthcare organization of roughly $2000 for individuals with knee osteoarthritis and $3000 for those with hip osteoarthritis.15 Use of patient decision support interventions was one of multiple interventions implemented, including monthly feedback of surgical rates to providers coupled with directives from leadership to decrease utilization rates. No costs were reported for the implementation of the interventions. There was an absolute difference of 12% in surgery utilization between patients with hip osteoarthritis in the control and intervention groups and an absolute difference of 7% for patients with knee osteoarthritis (that is, 12 fewer total hip replacements and seven fewer knee replacements for every 100 patients in the intervention group). Forty one percent of patients with hip osteoarthritis and 28% of patients with knee osteoarthritis in the intervention group actually received a decision support intervention. Paradoxically, treatment rates were 44% higher (for hip replacement) and 103% higher (for knee replacement) among the patients who actually received a decision support intervention.15

In 2010, Wennberg and Marr reported savings to the payer of healthcare services of $8 per member per month, accompanied a decrease in hospitalizations—namely, 13% in the usual care versus 12% in the enhanced care group.21 The reported cost of the intervention was $2 per individual per month; the method and variables used to calculate the costs, however, were not provided. The percentage of patients at risk for surgical intervention who were contacted by a health coach was 6.3% for the usual care group and 22.2% for the enhanced care group. Eleven percent in the control group and 41% in the enhanced group received a patient decision support intervention.

In 2013, Veroff and colleagues22 performed a subanalysis of the data first reported by Wennberg and Marr in 2010.21 The effect of the enhanced coaching intervention was larger in this subanalysis, with savings of $23 per member per month and 9.9% fewer elective surgeries. The costs associated with delivering the intervention were reported to be less than $5 per person per month. Of the patients with conditions that meant they were likely to have to make a decision about elective surgery, 7.5% in the usual care group and 22.8% in the enhanced care group were ultimately contacted by phone. Ten percent of people in the usual care group and 32% in the decision support intervention group received videos to assist them in shared decision making.22

This subanalysis made the same comparison between usual care, consisting of three attempted telephone calls versus enhanced support consisting of five calls. Both analyses were based on 174 120 individuals. The number of patients facing decisions about elective surgery reported by Wennberg and Marr in 2010 was 18 000 versus 60 000 reported by Veroff in 2013. In the subanalysis, Veroff and colleagues used a different and broader categorization of preference—sensitive conditions (D Veroff, 2013, personal communication). Only patients facing surgical decisions were eligible for the Wennberg and Marr study.

Overall, we found a high degree of heterogeneity in the methods used to evaluate costs and savings. In general, the quality of the economic analyses in the studies was low to moderate: values ranged from 0 to 7 with a median of 5 (appendix table C). Among the four analyses with significant savings, quality scores ranged from 0 to 7 out of 10.15 16 21 22 The trial of van Peperstraten and colleagues had a score of 7 but did not report significant savings.19

Across the analyses reporting costs, the estimated cost per patient of developing, disseminating, and implementing patient decision support interventions ranged from $2 to $400 per patient.15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Some estimates were based on the costs of printing materials, while others included estimates of resource use, staff time, and adjustments for altered workflow. The time horizon for data collection of costs and savings varied from three to 24 months. Authors performed sensitivity analyses in two studies.16 20 Incremental cost effectiveness ratios were not calculated.

Three of the four studies that reported significant savings also had the highest risk of bias. The analysis by Arterburn and colleagues had a risk of bias score of 6 out of 6,15 the analysis by Kennedy and colleagues had a score of 3,16 the Wennberg and Marr analysis had a score of 4,21 and the subanalysis by Veroff and colleagues had a score of 5.22 The risk was highest across studies for selection, detection, and reporting biases. Three of the four analyses that had the lowest scores for risk of bias found no significant savings17 18 20 (table 1). Three of the eight analyses did not describe their randomization sequence and allocation concealment. Missing data can bias results. Six analyses provided reasons for missing data, and there was often insufficient detail to be able to rule out selective reporting. There was also insufficient disclosure of funding sources and potential conflicts of interest (appendix table B).

Discussion

Principal findings

Of seven studies and eight analyses that focused on the possible savings associated with the use of decision support interventions for patients, four found significant cost savings. These four analyses, however, were of low to moderate quality and had high risk of bias. The analyses that did not find savings had higher quality scores and less risk of bias. It is important to note that none of the studies found increased spending associated with the use of patient decision support interventions. When screening for these studies, we found over 500 commentaries that were positive about the potential impact of these tools on spending, but we could not identify many empirical studies that provide definitive evidence for these views. While it is reasonable to argue from the existing evidence that patients will likely choose less intervention and become risk averse when better informed,1 23 24 25 it is not yet clear whether this effect will lead to savings at a system level. In short, in the small number of available studies, the quality of economic assessment is moderate and the risk of bias is high.

Results in context

Several themes emerged across the included studies. There is no agreed method for cost allocation when patient decision support interventions are developed and used. Comparisons are difficult, and there is a need for detail in the description of resource utilization, workflow alterations, and costs. The included studies lacked detail to allow generalization. Some studies, however, were undertaken before the availability of the internet, which provides low cost methods of information dissemination.

Longer follow-up periods are required, given the age range of patients and the conditions under investigation. A decision to forgo surgical intervention for heavy menstruation could be revisited later, with a different outcome. A two year follow-up period does not capture this possibility. Neither does the one year follow-up by Wennberg and Marr and Veroff capture the overall effects of patient decision support interventions on decisions regarding joint replacement procedures.21 22 Data from the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial show that after first viewing decision support interventions, 24% of patients who then elected for non-operative care eventually had surgical intervention during the four year study period.26

The implementation of patient decision support interventions is often accompanied by the use of other interventions. Arterburn and colleagues report the effects of decision support interventions while a number of additional efforts were simultaneously used, including provider education regarding variation in treatment rates, feedback to providers about their treatment rate compared with others within Group Health, and legislative efforts in Washington State to promote the use of decision support interventions.15 The intervention in the Wennberg and Marr21 study consisted of telephone contact by coaches to educate patients about their diagnosis, encourage healthier behaviors, and supply them with decision support interventions. Because of concurrent interventions like these, it is not clear whether the decision support interventions alone or the cluster of interventions were responsible for the effect.

One of the studies reported showed increased spending associated with use of patient decision support interventions, the others did not. Savings would depend on delivering decision support interventions to eligible patients, and this is known to be difficult.27 Most authors do not report the proportion of patients given decision support interventions. Arterburn and colleagues report that 41% of patients with hip osteoarthritis and 28% of patients with knee osteoarthritis in the intervention group received a decision support interventions.15 Paradoxically, treatment rates were 44% higher (for hip replacement) and 103% higher (for knee replacement) among the patients who actually received a decision support intervention, raising the possibility of increased rather than reduced spending had the distribution of decision support interventions been more successful. Other studies did not report this data.

Strengths and weakness of our study

We have attempted to avoid the limited relevance of reviews that include only randomized trials by including studies that have used other designs, but in doing so, the heterogeneity of comparisons increased. Strengths of this review include the prospective registration with PROSPERO; inclusive search terms; a well developed, tested, and reproducible search strategy; and adherence to review guidelines (PRISMA).

Our results add to the findings of the most recent Cochrane Review of randomized trials of decision support interventions for patients. Costs and savings were secondary outcomes assessed in four of the 86 studies reviewed by Stacey and colleagues,1 in which they stated that the evidence was inconclusive. Our systematic review captured those four trials plus three additional studies and one additional subanalysis published since 2009. The inclusion of non-randomized designs allowed us to capture analyses that are frequently cited by policy documents in the US. Furthermore, we assessed the quality of the economic analyses and the risk of bias for each analysis using recognized criteria.10 13

We acknowledge that the absence of evidence for savings does not mean we have evidence of an absence of savings, nor do our findings argue against the usefulness of these tools – we believe that there is a strong ethical imperative to share decisions with patients whenever possible.2 Better economic analyses are needed that detail cost allocation methods and use longer time horizons.10 Dynamic economic models, together with sensitivity analyses around key assumptions, might have promise while also allowing non-healthcare costs to be factored, like absenteeism, which are likely to be more prominent considerations for patients than providers. More comprehensive models might reduce the risk of inferring societal savings based on findings from a partial economic assessment in isolated local research trials.

Conclusion

We conclude that the current evidence does not allow us to make definitive statements about whether, when, and why patient decision support interventions could lead to savings. We caution against making claims of significant savings associated with future use, such as those made by the Lewin Group,8 AHRQ,9 and NHS bodies.5 6 7 Promise of significant savings risks failure to meet expectations and can jeopardize implementation efforts. There is undisputed added value in ensuring that patients are better informed by use of tools such as patient decision support interventions, and there is a tendency for patients to choose more conservative treatments, but so far there is insufficient evidence to be confident that the implementation of these tools will lead to system-wide savings.

What is already known on this topic

The use of patient decision support interventions as a means to generate healthcare savings has been widely advocated, but the extent and quality of evidence is unclear

What this study adds

A few studies provide evidence of savings but, overall, the risk of bias is high and economic assessments are of moderate quality and over short time periods.

We thank Anne Winter and Albert G Mulley for their comments and advice and Tom Mead, biomedical librarian, for his assistance with our search.

Contributors: GE initiated the study and is guarantor. All authors conducted the search, data extraction, analysis, synthesis of the results, and drafting of the article.

Funding: This study was funded by the Dartmouth Center for Health Care Delivery Science. CO’N was supported by an HRB Research Leaders Award 2013 (RL/2013/16).

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Declaration of transparency: The corresponding author affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported: no important aspects of the study have been omitted.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2014;348:g188

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Appendix: Search strategy, bias checklist, and quality appraisal

References

- 1.Stacey D, Bennett C, Barry MG, Col NF, Eden KB, Holmes-Rovner M, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;10:CD001431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elwyn G, Tilbert J, Montori VM. The ethical imperative for shared decision making. Eur J Pers Centered Med 2013;1:129-31. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Emanuel E, Tanden N, Altman S, Armstrong S, Berwick D, de Brantes F, et al. A systemic approach to containing health care spending. N Engl J Med 2012;367:949-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oshima Lee E, Emanuel EJ. Shared decision making to improve care and reduce costs. N Engl J Med 2013;368:6-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.AQUA: Advancing Quality Alliance. www.advancingqualitynw.nhs.uk/sandbox/SDM3/AQuA-Shared-Decision-Making-introduction.html.

- 6.NHS England commitment to shared decision making. NHS England, 2013. www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/pe/sdm/commitment/.

- 7.NHS Direct, 2010. www.nhsdirect.nhs.uk/en/News/NewsArchive/2010/NHSDirectPilotsANewApproachToPatientsTreatmentDecisions

- 8.Lewin Group. A path to high performance US health system. Technical documentation. Boston, 2008.

- 9.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Service delivery innovation profile. www.innovations.ahrq.gov/content.aspx?id=3836. AHRQ 2013.

- 10.Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Torrance GW, O’Brien BJ, Stoddart GL. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. 3rd ed. Oxford University Press, 2005.

- 11.Liberati A, Altman D, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009;339:b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shemilt A, Mugford M, Byford S, Drummond M, Eisenstein E, Knapp M, et al. Incorporating economics evidence. The role and relevance of economics evidence in Cochrane reviews. In: Higgins J, Green S, eds. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 51.0 (updated March 2011). Cochrane Collaboration, 2011:1-25.

- 13.Higgins J, Altman DG. Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins J, Altman D, Sterne J, eds. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). Cochrane Collaboration, 2011.

- 14.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33:159-74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arterburn DE, Wellman R, Westbrook E, Rutter C, Ross T, McCulloch D, et al. Introducing decision aids at group health was linked to sharply lower hip and knee surgery rates and costs. Health Aff 2012;31:2094-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kennedy A, Sculpher M, Coulter A, Dwyer N, Rees M, Abrams KR, et al. Effects of decision aids for menorrhagia on treatment choices, health outcomes, and costs: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002;288:2701-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murray E, Davis H, Tai SSS, Coulter A, Gray A, Haines A. Randomised controlled trial of an interactive multimedia decision aid on benign prostatic hypertrophy in primary care. BMJ 2001;323:493-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murray E, Davis H, Tai SS, Coulter A, Gray A, Haines A. Randomised controlled trial of an interactive multimedia decision aid on hormone replacement therapy in primary care. BMJ 2001;323:490-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Peperstraten A, Nelen W, Grol R, Zielhuis G, Adang E, Stalmeier P, et al. The effect of a multifaceted empowerment strategy on decision making about the number of embryos transferred in in vitro fertilisation: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010;341:c2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vuorma S, Teperi J, Aalto A-M, Hurskainen R, Kujansuu E, Rissanen P. A randomized trial among women with heavy menstruation—impact of a decision aid on treatment outcomes and costs. 2004;7:327-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wennberg D, Marr A. A randomized trial of a telephone care-management strategy. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1245-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Veroff D, Marr A, Wennberg DE. Enhanced support for shared decision making reduced costs of care for patients with preference-sensitive conditions. Health Aff 2013;32:285-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morgan MW, Deber RB, Llewellyn-Thomas HA, Gladstone P, Cusimano RJ, O’Rourke K, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of on interactive videodisc decision aid for patients with ischemic heart disease. J Gen Intern Med 2000;15:685-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frosch DL, Bhatnagar V, Tally S, Hamori CJ, Kaplan RM. Internet patient decision support: a randomized controlled trial comparing alternative approaches for men considering prostate cancer screening. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:363-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wagner E, Barrett P, Barry M, Barlow MJ, Fowler FJ Jr. The effect of a shared decision-making program on rates of surgery for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Med Care 1995;33:765-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weinstein JN, Tosteson TD, Lurie JD, Tosteson A, Blood E, Herkowitz H, et al. Surgical versus nonoperative treatment for lumbar spinal stenosis four-year results of the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial. Spine 2010;35:1329-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elwyn G, Scholl I, Tietbohl C, Mann M, Edwards AGK, Clay C, et al. “Many miles to go …” A systematic review of the implementation of patient decision support interventions into routine clinical practice. BMC Med Inf Decis 2013;13(supp 2):S14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen D, Longo MF, Hood K, Edwards A, Elwyn G. Resource effects of training general practitioners in risk communication skills and shared decision making competences. J Eval Clin Pract 2004;10;3:439-45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Davies S, Quintner J, Parsons R, Parkitny L, Knight P, Forrester E, et al. Preclinic group education sessions reduce waiting times and costs at public pain medicine clinics. Pain Med 2011;12:59-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix: Search strategy, bias checklist, and quality appraisal