Abstract

Background & Aims

Some women with urge-predominant fecal incontinence (FI) have diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome and a stiffer and hypersensitive rectum. We evaluated the effects of the α2-adrenergic agonist clonidine on symptoms and anorectal functions in women with FI in prospective, placebo-controlled trial.

Methods

We assessed bowel symptoms and anorectal functions (anal pressures, rectal compliance, and sensation) in 43 women (58±2 y old) with urge-predominant FI randomly assigned to groups given oral clonidine (0.1 mg, twice daily) or placebo for 4 weeks. Before and after administration of the test article, anal pressures were evaluated by manometry, and rectal compliance and sensation were measured using a barostat. Anal sphincter injury was evaluated by endoanal magnetic resonance imaging. Bowel symptoms were recorded in daily and weekly diaries. The primary endpoint was the FI and Constipation Assessment symptom severity score.

Results

FI scores decreased from 9.1±0.3 to 7.6±0.5 among subjects given placebo and from 8.1±0.4 to 6.5±0.6 among patients given clonidine. Clonidine did not affect FI symptom severity, bowel symptoms (stool consistency or frequency), anal pressures, rectal compliance, or sensation, compared to placebo. However, when baseline data were used to categorize subjects as those with or without diarrhea, clonidine reduced the proportion of loose stools in patients with diarrhea only (P=.018). Clonidine also reduced the proportion of days with FI in patients with diarrhea (P=.0825).

Conclusions

Overall, clonidine did not affect bowel symptoms, fecal continence, or anorectal functions, compared with placebo, in women with urge-predominant FI. Among patients with diarrhea, clonidine increased stool consistency, with a borderline significant improvement in fecal continence.

Keywords: FICA, randomized controlled trial, IBS, stool consistency, MRI

INTRODUCTION

Fecal incontinence (FI) is a relatively common problem, particularly in women and the elderly.1 While the symptom is often attributed to obstetric anal sphincter injury among women with FI in the community, the median age of onset is 62 years.2 Bowel disturbances and rectal urgency, rather than obstetric anal sphincter injury, are the most important risk factors for FI.3 Hence, guidelines recommend management of bowel disturbances where appropriate,4 followed if necessary by urge suppression techniques, biofeedback therapy, and subsequently surgery when necessary.1

However, a systematic Cochrane review of drug therapy of FI in 2010 concluded that there is “limited evidence to guide clinicians in the selection of drug therapies for fecal incontinence”;5 a Medline search with the terms “fecal incontinence” and “drug therapy” did not identify any controlled studies thereafter. Of the 13 trials, with 473 participants in this review, 11 were crossover studies with a short or no washout period between treatments. In 3 trials, anti-diarrheal agents (i.e., loperamide, diphenoxylate plus atropine) improved fecal continence more than placebo in patients with chronic diarrhea, not all of whom had FI. The use of loperamide is limited by its potency, resulting in constipation and abdominal pain, particularly when the dose is increased rapidly. Because data were limited, the Cochrane review concluded that “no meaningful statistical analyses” were possible.

In addition to bowel disturbances, there is increasing evidence for rectal sensorimotor dysfunctions (e.g., reduced rectal capacity and increased rectal sensitivity), particularly in women with urge-predominant FI.6, 7 These disturbances may be potentially amenable to modulation with clonidine, an α2-adrenergic agonist that can inhibit gastrointestinal motor activity by presynaptically inhibiting acetylcholine release from nerves in the myenteric plexus and at the neuromuscular junction. Independent of these actions, clonidine has anti-nociceptive effects mediated by α2 receptors in the spinal cord, brainstem, and forebrain.8 Clonidine reduced colonic and rectal tone, increased colonic and rectal compliance, and reduced colonic and rectal perception of distention in healthy subjects.9, 10 In an uncontrolled study, clonidine improved symptoms in women with FI and this improvement was associated with increased rectal compliance and reduced rectal sensitivity.11 Clonidine also improved symptoms in a controlled study in diarrhea-predominant IBS.12 Prior studies had shown association of SNPS in adrenergic receptor genes α2A (C-1291G) and α2C (Del 332-325) and IBS-C genotype,13 but not with colonic transit.14 A pharmacogenetic study suggested that rectal sensation (first sensation and urge, but not pain) in response to clonidine was influenced by α2A (C-1291G).15

Prompted by this rationale and findings, we conducted a double-blind placebo-controlled study evaluating the effects of clonidine on symptoms and anorectal sensorimotor functions in FI. Our hypothesis was that clonidine will improve symptoms and anorectal sensorimotor dysfunctions in women with urge-predominant FI.

MATERIAL & METHODS

Study Design

This was a double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study conducted at Mayo Clinic in the United States with the randomization balanced on age (<50 years vs. ≥0 years of age), BMI (<30 vs. ≥30 kg/m2), and hysterectomy versus no hysterectomy. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Mayo Clinic, registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT00884832), and conducted between January 2009 and April 2012. All authors had access to the study data and had reviewed and approved the final manuscript. Bowel symptoms were recorded during consecutive 4 week baseline and 4 week treatment periods. Anorectal sensorimotor functions were assessed on 1 day at the end of baseline and treatment periods. Bowel habits were recorded in daily diaries for 4 weeks at baseline and then for 4 weeks during treatment with clonidine. During the treatment period, patients were treated with oral clonidine (0.1 mg) or matching placebo twice daily.

Eligibility Criteria

Eligible participants were all women aged 18–75 years with urge-predominant FI for ≥1 year duration as defined by a validated questionnaire detailed below. Patients with current or prior, organic colonic or anorectal diseases (rectal cancer, scleroderma, inflammatory bowel disease, congenital anorectal abnormalities, Grade 2 or more severe rectal prolapse, history of rectal resection or pelvic irradiation), severe diarrhea during the run-in phase defined as an average of more than 6 liquid stools (Bristol 6 or 7) daily, clinically significant cardiovascular or pulmonary disease or EKG abnormalities [i.e., atrial flutter or fibrillation, sinus tachycardia (>110/minute) or bradycardia (<45 beats/minute), or prolonged QTc interval (>460 msec), symptomatic hypotension or systolic blood pressure of <100 mm Hg at initial screening visit, neurological disorders (i.e., spinal cord injury, dementia as evidenced by mini-mental status examination score <20/25, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, peripheral neuropathy), use of opiate analgesics, and pregnant or nursing women were excluded. Only subjects with urge or combined FI, as defined below, and 4 or more incontinent episodes during the 4-week baseline period were permitted to participate in the 4-week treatment phase. Patients were asked to refrain from making any major lifestyle changes (e.g., starting a new diet or changing their exercise pattern) during the trial.

Medications

Either placebo or oral clonidine was taken before meals twice a day. Clonidine (0.1 mg) tablets have a bioavailability of 99%; plasma levels are high for at least 4 hours after administration. Routine antidiarrheal treatment was not permitted during the screening or treatment periods. Loperamide tablets (2 mg) were provided for rescue when patients experienced intolerable diarrhea. Patients were required to record all study, rescue, and other medication intake during the 8-week study.

Symptom Assessments

During the screening visit, patients completed a validated questionnaire pertaining to bowel symptoms, abdominal discomfort, as well as severity and circumstances surrounding FI.16,17 The FI subscale of the Fecal Incontinence and Continence Assessment [FICA]), which incorporates the type, frequency, amount, and characteristics (i.e., urge, passive, or combined) of FI, was used to grade the severity of FI.16 Only patients who reported they were “often” or “usually” incontinent because they had “great urgency and could not reach the toilet on time” were considered to have urge FI and were eligible to participate in this study. Some patients with urge FI also had symptoms of passive FI (i.e., they were “often” or “usually” “unaware when the leakage was actually happening”). These patients were considered to have “combined” (i.e., urge and passive FI).

Participants recorded every (continent and incontinent) bowel movement in a bowel diary during baseline and treatment periods. Details included circumstances surrounding defecation, presence of urgency prior to defecation, the duration for which defecation could be deferred, stool form quantified by the Bristol scale,18 and satisfaction after defecation (e.g., sense of incomplete evacuation).

The severity of FI (FICA scale) and satisfaction with treatment (100 mm VAS scale which was anchored by the terms “not satisfied at all” and “completely satisfied”) was recorded by weekly questionnaires. The severity of FI and its impact on quality of life were also recorded by the Rockwood Fecal Incontinence Severity Index (FISI) and Quality of Life scales at 4 and 8 weeks.19, 20

Assessment of Anorectal Sensorimotor Functions

Anorectal functions were assessed on 1 day at the end of the 4 week baseline and treatment periods. After 2 sodium phosphate enemas (Fleets®, C.B. Fleet, Lynchburg, VA), anorectal testing (i.e., anal manometry and assessment of rectal compliance and sensation) was conducted in the left lateral position. Average anal resting and squeeze pressures were measured using high-definition manometry (Sierra Scientific Instruments, Los Angeles, CA). Rectal compliance and sensation were recorded using previously validated techniques with an electronic rigid piston barostat (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN).6 A conditioning distention followed by a rectal staircase distention (from 0 to 44 mm Hg or to maximum tolerated pressure, whichever came first, in 4-mm Hg steps at 1 minute intervals) was performed. Pressure-volume relationships were analyzed by a power exponential function and summarized by the pressure corresponding to half maximum volume (Prhalf) and rectal capacity (i.e., maximum volume).6, 21 Sensory thresholds for first sensation, desire to defecate, and urgency were recorded during the staircase distention. Subjects also rated the intensity of perception for the desire to defecate and discomfort on two separate 100 mm long visual analog scales (VAS) during balloon distentions 8, 16, 24, and 32 mm Hg greater than the operating pressure applied in random order.9

Endoanal MR Imaging of the Anal Sphincter

Endoanal MRI was performed as previously described using endoanal receiver and pelvic phased array coils with T2-weighted fast spin-echo imaging in 3 planes using a small field of view (12–14 cm).22, 23 A gastrointestinal radiologist characterized the internal and external anal sphincter appearance as follows: (0=normal; 1=mild focal thinning; 2=focal tear/scar; 3=atrophy; 4=atrophy and tear; 5=global thickening). Puborectalis appearance was also evaluated (0=normal; 1=mild asymmetry; 2=unilateral atrophy or tear, 3=bilateral atrophy or tear).

Assessment of Candidate Genotypes

Blood samples were evaluated for polymorphisms at adrenergic α2A (C-1291G) (rs 1800544) and α2C (Del 332-325) (rs2234888) receptors using polymerase chain reaction-based restriction fragment length polymorphism assays.13–15

Study End Points

The primary symptom end point was the weekly FICA symptom severity score averaged over 4 week baseline and treatment periods. Secondary symptom end points included mean per subject number of episodes of FI per day, number and proportion of days with FI, severity of FI (Rockwood score), impact of FI on quality of life (Rockwood score), satisfaction with treatment (i.e., a 100 mm visual analog scale anchored by the terms “Not satisfied at all [no relief of symptoms]” and “Completely satisfied [symptoms resolved]”), and rectal urgency (proportion of bowel movements preceded by urgency).

Statistical Analysis

An EXCEL spreadsheet of treatment assignments (balanced on age, hysterectomy and BMI using a block size of 4), was generated (ARZ) by computer and sent to the research pharmacy. Study personnel were blinded until the study was completed. For each subject, the bowel diary data (e.g., stool frequency and form) were first averaged per day and then separately for baseline and post-clonidine diaries. Treatment groups were compared using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with the corresponding baseline (run-in) value as the covariate for (i) FI parameters measured by daily diaries (i.e., mean number of episodes/day, number and proportion of days with FI/period, proportion of bowel movements preceded by urgency), (ii) FI parameters measured by weekly diaries (i.e., FICA symptom severity score, satisfaction with FI treatment, Rockwood symptom severity and QOL scores), and (iii) bowel function responses (stool frequency, consistency, and proportion of semi-formed bowel movements). Data were analyzed per intent-to-treat analysis using all subjects randomized. Missing values were imputed using the corresponding overall mean in all subjects with non-missing data, and an adjustment in the ANCOVA error degrees of freedom (i.e., subtracting one df for each missing value imputed), to obtain an appropriate error residual variance. Separate post hoc ANCOVA models evaluated whether treatment effects were influenced by presence or absence of diarrhea at baseline and presence or absence of anal injury by MRI.

The associations between changes in anorectal functions with changes in clinical features were assessed using the Spearman correlation coefficient.

The influence of α2A polymorphisms on bowel symptoms and FI were assessed by an ANCOVA. As α2C (Del 322–325) was rarely encountered, no further analyses were performed with this genotype.

All analyses used SAS® software (version 9.3, Cary NC) and continuous data are reported as mean ± SEM while discrete data as frequencies(%).

Sample size assessment

Based on the variability in FI symptoms at baseline in a previous (uncontrolled) study,11 it was estimated that a parallel group study with 20 subjects randomized to placebo or clonidine would provide approximately 80% power to detect a difference of 5 days or 2 units in FICA scores between treatment groups.

RESULTS

Clinical Features and Patient Flow

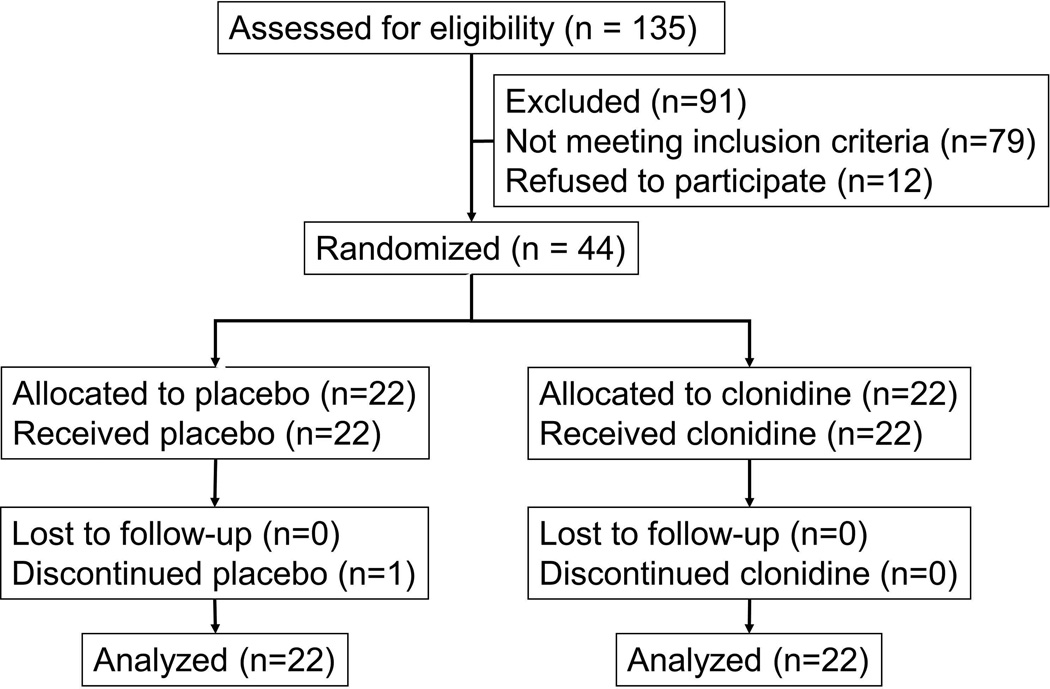

Figure 1 provides a flowchart of patient progression through the study. One subject randomized to placebo discontinued study medication due to side effects during week 4. Study groups were well balanced on age, BMI, and hysterectomy (Table 1). Thirty-six patients had bowel symptoms.

Figure 1. Consort Diagram.

All randomized patients completed studies and were included in the analysis.

Table 1.

Demographic and Baseline Characteristics of the Patients

| Placebo (n=22) |

Clonidine (n=22) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 57 ± 3 | 58 ± 2 |

| Body-mass index§ (kg/m2) | 28.0. ± 1.4 | 30.3 ± 1.1 |

| Hysterectomy | 11 | 9 |

| Bowel habits | ||

| Stool frequency/day | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.2 |

| Stool consistency (Bristol stool form score) | 4.0 ± 0.2 | 3.7 ± 0.2 |

| Bristol form 5–7 (% of all bowel movements) | 41 ± 5 % | 31 ± 5 % |

| Duration for which defecation could be deferred (minutes) | 4.4 ± 1.3 | 3.6 ± 0.7 |

| Proportion of complete bowel movements (%) | 51 ± 6 | 71 ± 7 |

| Functional bowel disorders | ||

| Functional diarrhea or D-IBS | 13 | 9 |

| Functional constipation or C-IBS | 5 | 2 |

| Diarrhea and constipation | 4 | 3 |

| Rectal urgency | ||

| Bowel movements preceded by urgency (%) | 59 ± 5 | 55 ± 4 |

| Incontinent bowel movements preceded by urgency (%) | 74 ± 6 | 75 ± 7 |

| Fecal incontinence | ||

| Number of days with FI | 16 ± 2 | 13 ± 1 |

| Number of FI episodes | 31 ± 5 | 20 ± 3 |

| Proportion of bowel movements which were incontinent (%) | 40 ± 6 | 31 ± 4 |

| Volume of FI | ||

| Staining only (%) | 19 ± 4 | 11 ± 3 |

| Moderate FI (%) | 13 ± 3 | 12 ± 3 |

| Full bowel movement (%) | 8 ± 2 | 8 ± 2 |

| Composition of leakage | ||

| Bristol form 5–7 (% of all incontinent bowel movements | 57 ± 7 % | 54 ± 7 % |

| Symptom severity score (max = 13) | 9.1 ± 0.3 | 8.1 ± 0.4 |

Data for bowel habits are derived from daily diaries

Plus–minus values are means ± SEM

The duration of FI ranged from <2 years (n=10), between 2–10 years (n=20), and >10 years (n=14); 29 had isolated urge FI and 15 had combined (i.e., passive and urge) FI. Forty-three patients were incontinent either for solid stools alone (16 patients) or for liquid and solid stools (27 patients); one patient was incontinent for liquid stools alone. The typical amount of leakage was small (i.e., staining only, n=11), moderate (i.e., more than staining but not a full bowel movement, n=22), or large (i.e., a full bowel movement, n=11). Integrating these parameters, the FICA incontinence symptom severity score suggested moderate (25 patients) or severe FI (19 patients).

Primary and Secondary End Points –FI

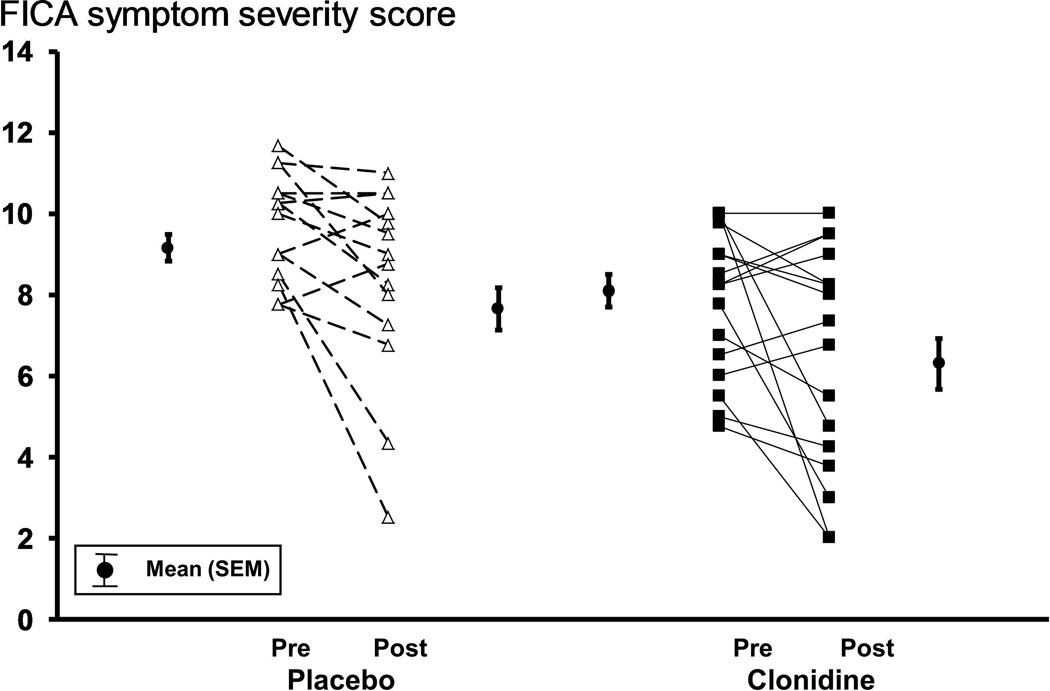

The FICA symptom severity score declined, reflecting improved continence, to a comparable extent in patients treated with placebo and clonidine; differences were not significant (Table 2, Figure 2). Likewise, the Rockwood symptom severity scores was also lower while the Rockwood quality of life score and satisfaction with treatment scores were higher during treatment with placebo and separately clonidine; differences were not significant (Table 2).

Table 2.

Primary, Secondary and Additional End Points

| Placebo | Clonidine | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | During | Before | During | |

| Bowel habits | ||||

| Stool frequency/day | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.1 |

| Stool consistency (Bristol stool form score) | 4.0 ± 0.2 | 3.8 ± 0.2 | 3.7 ± 0.2 | 3.4 ± 0.2 |

| Bristol form 5–7 (% of all bowel movements) | 41 ± 5 % | 36 ± 6 | 31 ± 5 | 21 ± 4 |

| Duration for which defecation could be deferred (minutes) | 4.4 ± 1.3 | 5.2 ± 1.5 | 3.6 ± 0.7 | 5.6 ± 1.9 |

| Proportion of complete bowel movements (%) | 51 ± 6 | 60 ± 6 | 71 ± 7 | 72 ± 7 |

| Rectal urgency | ||||

| Bowel movements preceded by urgency (%) b | 59 ± 5 | 46 ± 6 | 55 ± 4 | 46 ± 6 |

| Incontinent bowel movements preceded by urgency (%) | 74 ± 6 | 69 ± 7 | 75 ± 7 | 71 ± 8 |

| Fecal incontinence | ||||

| Number of days with FI b | 16 ± 2 | 11 ± 2 | 13 ± 1 | 8 ± 1 |

| Number of FI episodes b | 31 ± 5 | 19 ± 4 | 20 ± 3 | 12 ± 3 |

| Proportion of bowel movements which were incontinent (%) | 40 ± 6 | 27 ± 6 | 31 ± 4 | 24 ± 5 |

| Volume of FI (% of all bowel movements) | ||||

| Staining only (%) | 19 ± 4 | 17 ± 5 | 11 ± 3 | 9 ± 2 |

| Moderate FI (%) | 13 ± 3 | 7 ± 2 | 12 ± 3 | 7 ± 3 |

| Full bowel movement (%) | 8 ± 2 | 4 ± 1 | 8 ± 2 | 7 ± 2 |

| Composition of leakage | ||||

| Bristol form 5–7 (% stools) | 57 ± 7 | 57 ± 8 | 54 ± 7 | 46 ± 9 |

| Mean weekly FICA symptom severity score a # (maximum = 13) | 9.1 ± 0.3 | 7.6 ± 0.5 | 8.1 ± 0.4 | 6.5 ± 0.6 |

| Fecal incontinence severity index (Rockwood score) b † | 37.3 ± 2.5 | 31.2 ± 2.5 | 36.2 ± 2.7 | 29.3 ± 2.8 |

| Fecal incontinence quality of life (Rockwood score) b † | ||||

| Lifestyle score | 2.3 ±0.2 | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 3.1 ± 0.2 |

| Coping score | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 2.3 ± 0.2 |

| Depression score | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 3.5 ± 0.1 |

| Embarrassment score | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 2.8 ± 0.2 |

| Satisfaction with therapy (100 mm VAS) b # | 18 ± 4 | 38 ± 6 | 22 ± 6 | 47 ± 6 |

| Loperamide use (% days) b | 4 ± 2 | 5 ± 2 | 3 ± 1 | 2 ± 0 |

All parameters were computed from daily diaries except for those marked with # (weekly diaries) and † (pre and post treatment questionnaire)

Primary endpoint

Secondary endpoint

Figure 2. Comparison of FICA scores before and during treatment.

The number of days on which patients had at least one episode of FI declined from 16±2 days before to 11±2 days during treatment with placebo and from 13±1 days before to 8±1 days after during clonidine (Table 2). The number of episodes of FI was also lower during treatment with clonidine and separately placebo. Differences between placebo and clonidine were not significant. Fifteen patients (8 placebo, 7 clonidine) reported a ≥50% reduction in the number of days with FI and 12 (7 placebo, 5 clonidine) reported a ≥50% reduction in the number of episodes of FI.

Primary and Secondary End Points – Bowel Disturbances

Drug effects on bowel habits (i.e., stool consistency, frequency, and urgency) were not significant (Table 2). Patients used loperamide for ≤5% of days before and during therapy.

Comparison of Effects of Clonidine in Patients with and without Diarrhea

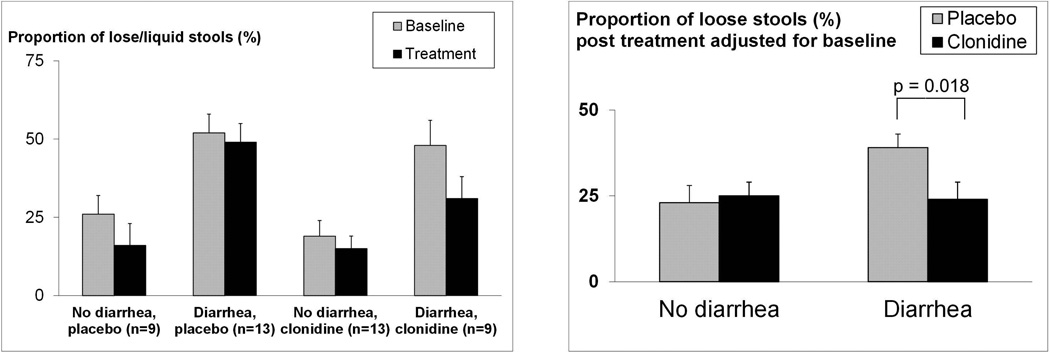

At baseline, 13 of 22 subjects in the placebo group and 9 of 22 in the clonidine group had functional diarrhea or diarrhea-predominant IBS by questionnaire-based criteria. During the 4 week baseline period, the mean (±SEM) Bristol stool form score was associated with diarrhea subgroup (p<0.001) being higher in patients with (4.3±0.2) versus without (3.4±0.2) diarrhea, indicative of looser stools. Expressed differently, the proportion of semi-formed and lose stools (Bristol form 5–7) was also associated with diarrhea subgroup (p<0.001), again higher in patients with (50±5%) versus without (22±4%) diarrhea (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Effects of clonidine and placebo on the proportion of semi-formed and loose stools (i.e., Bristol form score of 5–7).

Left panel. The proportion of semi-formed and lose stools (Bristol form 5–7) was higher (p<0.001) in patients with diarrhea. Right panel. In patients with diarrhea, clonidine reduced (p=0.018) the proportion of semi-formed and loose stools compared to placebo.

Differential effects of clonidine (p=0.047, drug*group interaction) were observed for the proportion of semi-formed and loose bowel movements during treatment adjusted for baseline (Figure 3). Clonidine reduced the proportion of semi-formed and loose stools in patients with diarrhea to a greater extent (p=0.018) than in patients without diarrhea (p=0.68). In contrast to stool consistency, drug effects on other bowel characteristics (i.e., mean stool frequency and urgency) were not influenced by baseline diarrhea subgroup status.

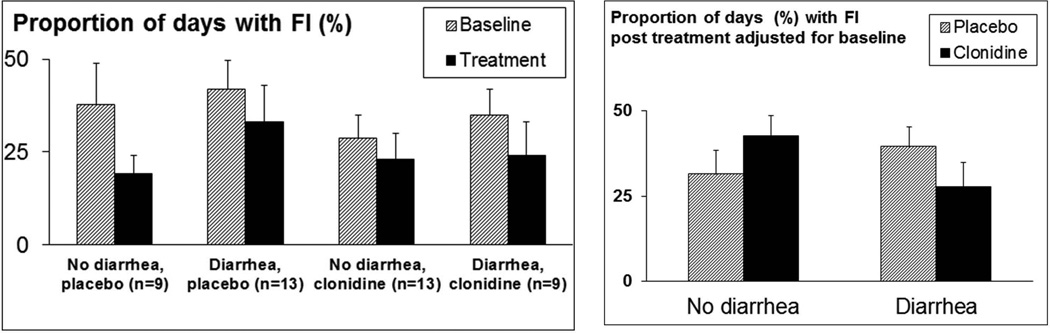

Differential effects of clonidine were also observed in the diarrhea subgroup compared to the non-diarrhea subgroup for mean number of FI episodes (p=0.097 for drug*group interaction) and the proportion of days with FI (p=0.082 for drug*group interaction) with more pronounced effects in patients with diarrhea (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Comparison of effects of clonidine on FI in patients with and without diarrhea.

Left panel. In all 4 groups, the proportion of days with FI was lower during treatment. Patients with diarrhea had more days with FI at baseline. Right panel. Proportion of days with FI during treatment adjusted for baseline differences. In the diarrhea group, patients randomized to clonidine had a smaller proportion of days with FI compared to placebo. In patients without diarrhea, the converse was observed (p=0.082 for differential treatment effect).

Effects on Anorectal Functions

Relevant anorectal dysfunctions at baseline included low anal resting (12 patients) or squeeze pressures (21 patients), reduced rectal capacity and/or compliance (27 patients), increased rectal sensitivity (i.e., reduced rectal volume [9 patients] or volume and pressure thresholds [7 patients] for the desire to defecate or urgency), decreased rectal sensitivity (i.e., increased rectal pressure [10 patients] or volume and pressure thresholds [1 patient] for the desire to defecate or urgency). Clonidine did not significantly affect anal resting or squeeze pressures, rectal capacity, compliance or sensation assessed by sensory thresholds, or VAS scores during rectal distention (Supplementary Table 1). Correlations of changes during treatment in symptoms (i.e., number of days and episodes of FI, rectal urgency, and stool consistency) separately with rectal compliance and capacity and sensory thresholds were not significant (data not shown).

Relationship between Anal Sphincter Injury and Effects of Clonidine

Endoanal imaging disclosed “no injury” in 20 patients, significant tears in 12 and atrophy in 12 patients. Ten patients without and 12 patients with anal injury were randomized to clonidine. Injury status predicted effects of clonidine on the number of episodes of FI (p=0.04). Among patients without injury, 2 of 10 (placebo) and 4 of 10 (clonidine) reported a ≥50% reduction in the number of episodes of FI (p=0.06). Corresponding figures among patients with injury were 5 of 12 (placebo) but only 1 of 12 (clonidine). Thus, clonidine reduced the frequency of FI to a greater extent in patients without anal injury. There was a similar but not significant (p=0.32) pattern in the number of patients who had a ≥50% reduction in the number of days with FI.

Relationship between α2-adrenergic Polymorphisms and Therapeutic Effects

Given the effect of clonidine on stool consistency, we explored the association of response to clonidine and genetic variation in α2A receptor. However the α2A-C1291G polymorphism did not predict effects of clonidine (Supplementary Material).

Adverse Effects

Thirteen patients who received placebo and a higher (p=0.03) proportion who received clonidine (i.e., 20 patients) had side effects. The incidence of dry mouth (placebo [1 subject], clonidine [11 subjects]) was also higher (p<0.002) during clonidine treatment. Drowsiness (placebo [3 subjects], clonidine [4 subjects]), lightheadedness (placebo [2 subjects], clonidine [5 subjects]) fatigue (placebo [4 subjects], clonidine [4 subjects]) were not significantly more common during clonidine therapy.

DISCUSSION

In contrast to our previous uncontrolled study,11 clonidine’s overall effects on bowel symptoms, fecal continence, and anorectal functions were not significant compared to placebo in this study. Confirming prior observations, clonidine significantly reduced stool consistency in patients with diarrhea.12 Its effects on fecal continence were borderline significant in patients with diarrhea at baseline and separately in patients without anal injury by MRI.

We considered four potential reasons that might explain the lack of efficacy of clonidine, i.e., a floor effect due to very mild baseline symptoms, greater than anticipated placebo response, larger than expected variation, and true lack of drug effects. A “floor” effect seems unlikely because all patients had moderate symptoms or worse at baseline. Nearly 50% (21 patients) had an average of 5 FI episodes per week and, more than one-third of all bowel movements were incontinent,, and 57% of incontinent stools were characterized by more than a stain, which is a useful index of FI that has not been quantified in other therapeutic trials. The FICA symptom scoring system is the only symptom severity index of FI that incorporates all 4 ingredients of FI.16, 17

Except for the number of FI episodes, FI parameters were not significantly different between placebo and clonidine groups. However, the placebo response rate was high. Forty one percent of patients treated with placebo had a 50% or greater reduction in the number of days or episodes with FI. This placebo response rate is comparable to previous studies with diarrhea-predominant IBS24 and, using a different criterion, higher than the placebo response rate (i.e., 32%) in a trial of the perianal bulking agent, dextranomer, for FI.25 In the pivotal uncontrolled, multicenter trial of sacral nerve stimulation, 86% of patients reported a ≥50% reduction in the number of FI episodes per week compared to baseline and 40% achieved perfect continence.26 While these effects of sacral nerve stimulation are substantially better than the effects of clonidine, that study, like most other therapeutic trials in FI, was uncontrolled. The high placebo response rate, which has been noted previously, 27 underscores the need for controlled therapeutic trials in FI.

At baseline, 50% of patients had diarrhea. During the 4 week baseline period, the mean Bristol stool form score was 0.9 units higher in patients with diarrhea, reflecting looser stools. Expressed differently, the proportion of all stools which were semi-formed or loose (Bristol score 5–7) was more than twofold higher (50% vs 22%) in patients with diarrhea. The significance of this difference can be more readily translated to FI than mean stool consistency since incontinent stools were more likely to be loose (i.e., 57% versus 41% for all [i.e., continent and incontinent] bowel movements), confirming a previous study.28 Clonidine increased stool consistency only in patients with diarrhea and while results were not statistically significant, clonidine also improved continence in patients with diarrhea. Based on these findings, which extend a previous study of clonidine in diarrhea-predominant IBS,12 clonidine should be considered in diarrhea-predominant IBS refractory to other agents. The antidiarrheal properties of a higher dose of oral clonidine (0.3 mg) in healthy people are largely mediated by reduced gut motility and to a lesser extent by increased intestinal mucosal absorption of fluids.29 However, the effects of 0.1 mg oral clonidine on intestinal absorption are unknown; this dose did not affect gastric emptying, small intestinal or colonic transit in humans.12

In our prior uncontrolled study with a similar dose (0.2 mg daily) of transdermal clonidine, overall effects on anorectal functions were not significant. However, effects on symptoms were correlated with effects on rectal compliance and sensation.11 Clonidine has dose-dependent effects on colonic and rectal compliance and sensation in healthy subjects, which are most evident for the 0.3 mg dose.9, 30 Perhaps this dose (0.1 mg) was insufficient. Alternatively, the finding that clonidine’s effects on rectal compliance were less pronounced than previously observed in healthy subjects30 may suggest that fibrosis rather than increased tone contributes to increased rectal stiffness in women with FI. Since somnolence is common with 0.3 mg twice daily, future controlled trials should evaluate a higher dose of clonidine (e.g., 0.15 or 0.2 mg bid), particularly in patients with diarrhea-predominant IBS and FI. Indeed, somnolence is a reversible and generally not a noxious side effect, clonidine at an oral dose starting at 0.1 mg and increasing to 0.2 mg twice daily may be considered in patients with diarrhea and FI. The observed mean (±SD) FICA score at baseline in those with diarrhea was 9.82 (±1.44). Based on these data a controlled study of 10 subjects per treatment arm randomized to clonidine or placebo would provide 80% power (at a 2-sided α level of 0.05) to detect a difference in mean FICA scores between treatment groups of 2 points (e.g. 9.8 vs 7.8) while 5 per group would provide 80% power to detect a 3 point difference.

Previous studies suggest that the gastrointestinal effects of clonidine are influenced by polymorphisms at adrenergic α2A (C-1291G) receptors.15 However, these polymorphisms were not associated with baseline colonic transit in IBS14 nor with the response to clonidine in this study. This finding is subject to the caveat that based on the observed prevalence of CC and CG/GG polymorphisms, there was ~80% power to detect differences corresponding to approximately 2.25 SDs.

In summary, oral clonidine (0.1 mg bid) did not significantly improve fecal continence or bowel habits in women with urge-predominant fecal continence. However, the data suggest that a subset of women with diarrhea and FI may benefit from clonidine.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Support:

The project described was supported by USPHS NIH Grant R01 DKDK78924 and Grant Number 1 UL1 RR024150* from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH. Information on NCRR is available at http://www.ncrr.nih.gov/. Information on Reengineering the Clinical Research Enterprise can be obtained from http://nihroadmap.nih.gov.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Guarantor of the Article: Adil E. Bharucha

Specific Author Contributions:

Adil E. Bharucha - study concept and design; acquisition of data; interpretation of data; drafting and critically revising the manuscript; statistical analysis; obtained funding; study supervision

J.G. Fletcher - acquisition and interpretation of data

Michael Camilleri – analysis and interpretation of data

Jessica Edge - acquisition and interpretation of data

Paula Carlson - analysis and interpretation of data

Alan R. Zinsmeister - study concept and design; statistical analysis; critically revising the manuscript for important intellectual content

All authors reviewed the final version of the manuscript

Potential Competing Interests: none

REFERENCES

- 1.Whitehead WE, Bharucha AE. Diagnosis and treatment of pelvic floor disorders: what's new and what to do. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:1231–1235. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.02.036. 1235. e1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bharucha AE, Zinsmeister AR, Locke GR, Seide B, McKeon K, Schleck CD, Melton LJI. Prevalence and burden of fecal incontinence: A population based study in women. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:42–49. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bharucha AE, Zinsmeister AR, Schleck CD, Melton LJ., 3rd Bowel disturbances are the most important risk factors for late onset fecal incontinence: a population-based case-control study in women. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1559–1566. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bharucha AE, Wald AM. Anorectal disorders. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2010;105:786–794. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheetham MJ, Brazzelli M, Norton CC, Glazener CMA. Drug treatment for faecal incontinence in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bharucha AE, Fletcher JG, Harper CM, Hough D, Daube JR, Stevens C, Seide B, Riederer SJ, Zinsmeister AR. Relationship between symptoms and disordered continence mechanisms in women with idiopathic fecal incontinence. Gut. 2005;54:546–555. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.047696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andrews C, Bharucha AE, Camilleri M, Low PA, Seide B, Burton D, Baxter K, Zinsmeister AR. Rectal sensorimotor dysfunction in women with fecal incontinence. American Journal of Physiology - Gastrointestinal & Liver Physiology. 2007;292:G282–G289. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00176.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Unnerstall JR, Kopajtic TA, Kuhar MJ. Distribution of alpha 2 agonist binding sites in the rat and human central nervous system: analysis of some functional, anatomic correlates of the pharmacologic effects of clonidine and related adrenergic agents. Brain Research. 1984;319:69–101. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(84)90030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bharucha AE, Camilleri M, Zinsmeister AR, Hanson RB. Adrenergic modulation of human colonic motor and sensory function. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;273:G997–G1006. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.273.5.G997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malcolm A, Camilleri M, Kost L, Burton D, Fett S, Zinsmeister A. Towards Identifying Optimal Doses For Alpha-2 adrenergic Modulation of Colonic and Rectal Motor and Sensory Function. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2000;14:783–793. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bharucha AE, Seide BM, Zinsmeister AR. The effects of clonidine on symptoms and anorectal sensorimotor function in women with faecal incontinence. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2010;32:681–688. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04391.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Camilleri M, Kim D-Y, McKinzie S, Kim H-J, Thomforde G, Burton D, Low PA, Zinsmeister AR. A randomized, controlled exploratory study of clonidine in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Clinical Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2003;1:111–121. doi: 10.1053/cgh.2003.50019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim HJ, Camilleri M, Carlson PJ, Cremonini F, Ferber I, Stephens D, McKinzie S, Zinsmeister AR, Urrutia R. Association of distinct alpha(2) adrenoceptor and serotonin transporter polymorphisms with constipation and somatic symptoms in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gut. 2004;53:829–837. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.030882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grudell ABM, Camilleri M, Carlson P, Gorman H, Ryks M, Burton D, Baxter K, Zinsmeister AR. An exploratory study of the association of adrenergic and serotonergic genotype and gastrointestinal motor functions. Neurogastroenterology & Motility. 2008;20:213–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2007.01026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Camilleri M, Busciglio I, Carlson P, McKinzie S, Burton D, Baxter K, Ryks M, Zinsmeister AR. Pharmacogenetics of low dose clonidine in irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterology & Motility. 2009;21:399–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01263.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bharucha AE, Locke GR, Seide B, Zinsmeister AR. A New Questionnaire for Constipation and Fecal Incontinence. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2004;20:355–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bharucha AE, Zinsmeister AR, Locke GR, Schleck C, McKeon K, Melton LJ. Symptoms and quality of life in community women with fecal incontinence. Clinical Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2006;4:1004–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heaton KW, O'Donnell LJ. An office guide to whole-gut transit time. Patients' recollection of their stool form. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 1994;19:28–30. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199407000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rockwood TH, Church JM, Fleshman JW, Kane RL, Mavrantonis C, Thorson AG, Wexner SD, Bliss D, Lowry AC. Patient and surgeon ranking of the severity of symptoms associated with fecal incontinence: the fecal incontinence severity index. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 1999;42:1525–1532. doi: 10.1007/BF02236199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rockwood TH, Church JM, Fleshman JW, Kane RL, Mavrantonis C, Thorson AG, Wexner SD, Bliss D, Lowry AC. Fecal incontinence quality of life scale: quality of life instrument for patients with fecal incontinence. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 2000;43:9–16. doi: 10.1007/BF02237236. discussion 16-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Law NM, Bharucha AE, Undale AS, Zinsmeister AR. Cholinergic stimulation enhances colonic motor activity, transit, and sensation in humans. American Journal of Physiology - Gastrointestinal & Liver Physiology. 2001;281:G1228–G1237. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.5.G1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fletcher JG, Busse RF, Riederer SJ, Hough D, Gluecker T, Harper CM, Bharucha AE. Magnetic resonance imaging of anatomic and dynamic defects of the pelvic floor in defecatory disorders. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2003;98:399–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bharucha AE, Fletcher JG, Melton LJ, 3rd, Zinsmeister AR. Obstetric Trauma, Pelvic Floor Injury And Fecal Incontinence: A Population-Based Case-Control Study. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2012;107:902–911. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ford AC, Moayyedi P. Meta-analysis: factors affecting placebo response rate in the irritable bowel syndrome. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2010;32:144–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Graf W, Mellgren A, Matzel KE, Hull T, Johansson C, Bernstein M. Efficacy of dextranomer in stabilised hyaluronic acid for treatment of faecal incontinence: a randomised, sham-controlled trial. The Lancet. 2011;377:997–1003. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62297-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mellgren A, Wexner SD, Coller JA, Devroede G, Lerew DR, Madoff RD, Hull T. Group SNSS. Long-term efficacy and safety of sacral nerve stimulation for fecal incontinence. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 2011;54:1065–1075. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31822155e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Norton C, Chelvanayagam S, Wilson-Barnett J, Redfern S, Kamm MA. Randomized Controlled Trial of Biofeedback for Fecal Incontinence. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1320–1329. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2003.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bharucha AE, Seide B, Zinsmeister AR, Melton JL. Relation of bowel habits to fecal incontinence in women. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2008;103:1470–1475. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01792.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schiller LR, Santa Ana CA, Morawski SG, Fordtran JS. Studies of the antidiarrheal action of clonidine. Effects on motility and intestinal absorption. Gastroenterology. 1985;89:982–988. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(85)90197-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Viramontes BE, Malcolm A, Camilleri M, Szarka LA, McKinzie S, Burton DD, Zinsmeister AR. Effects of an alpha(2)-adrenergic agonist on gastrointestinal transit, colonic motility, and sensation in humans. American Journal of Physiology - Gastrointestinal & Liver Physiology. 2001;281:G1468–G1476. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.6.G1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.