Abstract

Study Objectives:

To examine the prospective, reciprocal association between sleep deprivation and depression among adolescents.

Design:

A community-based two-wave cohort study.

Setting:

A metropolitan area with a population of over 4 million.

Participants:

4,175 youths 11-17 at baseline, and 3,134 of these followed up a year later.

Measurements:

Depression is measured using both symptoms of depression and DSM-IV major depression. Sleep deprivation is defined as ≤ 6 h of sleep per night.

Results:

Sleep deprivation at baseline predicted both measures of depression at follow-up, controlling for depression at baseline. Examining the reciprocal association, major depression at baseline, but not symptoms predicted sleep deprivation at follow-up.

Conclusion:

These results are the first to document reciprocal effects for major depression and sleep deprivation among adolescents using prospective data. The data suggest reduced quantity of sleep increases risk for major depression, which in turn increases risk for decreased sleep.

Citation:

Roberts RE; Duong HT. The prospective association between sleep deprivation and depression among adolescents. SLEEP 2014;37(2):239-244.

Keywords: Depression, sleep deprivation, adolescents, epidemiology

INTRODUCTION

Sleep deprivation, or short sleep, is sleep time less that the average basal level of about 9 hours per night for adolescents.1 Studies indicate that many adolescents do not obtain adequate nocturnal sleep.2–12 As many as one-fourth of adolescents report sleeping 6 hours or less per night.12,13

There is consensus concerning changes in the transition from childhood to adolescence that result in increased sleep deprivation in adolescence. Transition to an earlier school start time, along with pubertal phase delay, significantly affect the quality of sleep, sleep-wake schedule, and daytime behavior. The combination of the phase delay, late-night activities or jobs, and early morning school demands can significantly constrict hours available to sleep.12,14–17 Laboratory studies using longitudinal designs have documented consistent changes in sleep/wake architecture in adolescents.18–20 These changes become particularly pronounced from early to late puberty.21,22

Research has been conducted on the correlates of sleep disturbance and sleep deprivation among adolescents.13–15,23–25 The available evidence suggests that disturbed sleep and sleep deprivation are associated with deficits in functioning across a wide range of indicators of psychological, interpersonal, and somatic well-being. For example, adolescents with disturbed sleep report more depression, anxiety, anger, inattention and conduct problems, drug and alcohol use, impaired academic performance, and suicidal thoughts and behaviors. They also have been reported to have more fatigue, less energy, worse perceived health, and symptoms such as headaches, stomach aches, and backaches. Laboratory studies in particular have documented impaired cognitive function, daytime sleepiness, and fatigue as a consequence of sleep deprivation.14,21,22

However, almost all of the epidemiologic data on these associations emanate from prevalence or cross-sectional surveys. Thus, the question of whether, for example, sleep deprivation increases the risk of functional impairment among adolescents, or emotional, behavioral, and interpersonal problems increase the risk of sleep deprivation, remains unclear.

Roberts et al. examined the effects of deep deprivation among adolescents and found that short sleep (≤ 6 h) increased subsequent risk for school problems, low life satisfaction, poor perceive health, depressed mood, drug use, and poor grades.24 Other studies also have found that sleep problems, including sleep deprivation, increased the odds of subsequent mental health problems,6,26–29 including depressed mood.

Clearly, there appears to be an association between short sleep duration and symptoms of depressed mood. Again, while much of this evidence is from cross-sectional or prevalence studies, prospective or longitudinal studies also find short sleep increases risk for disturbed mood. However, to our knowledge, there are few data relating to the converse, i.e., that depressed mood increases risk for short sleep. Roberts et al. report that depressed mood (symptoms of depression) at baseline did not increase risk of restricted sleep (≤ 6 h) a year later.13

But what about the association between short sleep duration and clinical depression (e.g., major depression)? There is an extensive literature on the association between insomnia and major depression, particularly among adults,30–34 as well as some data on adolescents.35–37 The evidence indicates that insomnia, particularly chronic insomnia, increases subsequent risk of major depression. The evidence thus far, albeit limited, suggests that major depression confers little risk for developing insomnia. In a previous study, we found insomnia increased risk of major depression, but the reverse was not true.38 But, to our knowledge, no study to date has examined the prospective association between sleep deprivation and major depression among adolescents.

That was the focus of our research. We examined the prospective association between short sleep or sleep deprivation and major depression in adolescence. Using data from a two-wave cohort study of youths 11-17 years at baseline, Teen Health 2000 (TH2K), we examined the reciprocal association between short sleep and major depression, e.g., whether short sleep increases the risk for major depression, whether major depression increases the risk for short sleep, whether the association is asymmetric, or whether there is an association at all. The answers to this question have both etiologic and clinical implications. If there are reciprocal effects, then each partially accounts for the other in a causal way. Understanding the epidemiology of one requires understanding the other. On the other hand, if there is bi-directionality, clinically the presence of one suggests assessment and intervention for the other. We may need to focus on both for optimal effect.

METHODS

Sample

The sample was selected from households in the Houston metropolitan area enrolled in two local health maintenance organizations. One youth, aged 11 to 17 years, was sampled from each eligible household, oversampling for ethnic minority households. Initial recruitment was by telephone contact with parents. A brief screener was administered on ethnic status of the sample youths and to confirm data on age and sex of youths. Every household with a child 11 to 17 years of age was eligible. Because there were proportionately fewer minority subscriber households, sample weights were developed and adjusted by post-stratification to reflect the age, ethnic, and sex distribution of the 5-county Houston metropolitan area in 2000. The precision of estimates are thereby improved and sample selection bias reduced to the extent that it is related to demographic composition.39 Thus, the weighted estimates generalize to the population 11 to 17 years of age in a metropolitan area of 4.7 million people.

Data were collected on sample youths and one adult care-giver using computer-assisted personal interviews and self-administered questionnaires. The computerized interview contained the structured psychiatric interview (see below) and demographic data on the youths and the household. Height and weight measures were conducted after the completion of the interviews. The interviews and measurements were conducted by trained lay interviewers. The interviews took on average 1 to 2 h, depending on the number of psychiatric problems present. Interviews, questionnaires, and measurements were completed with 4,175 youths at baseline, representing 66% of the eligible households. There were no significant differences among ethnic groups in completion rates. Youths and caregivers were followed up approximately 12 months later, using the same assessment battery used at baseline. The cohort consisted of 3,134 youths plus their caregivers in Wave 2 (75% of Wave 1 dyads). All youths and parents gave written informed consent prior to participation. All study forms and procedures were approved by the University of Texas Health Science Center Committee for Protection of Human Subjects.

Measures

Depression

Depression was measured using two alternate strategies. We examined major depression, defined as a major depressive episode in the previous 12 months (prevalence was 1.7%) using DSM-IV criteria and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, Version IV (DISC-IV) as the diagnostic instrument.44 Then, given that much of the literature has focused on symptoms of depression, we examine disturbed mood in the past 12 months, defined as depressed mood, irritable mood, or anhedonia (baseline prevalence was 57.6%).

Data on psychiatric disorders were collected using the youth version of the DISC-IV, a highly structured instrument with demonstrated reliability and validity.44 Interviews were conducted by college-educated lay interviewers who had been extensively trained using protocols provided by Columbia University.41,42 Interviews with the DISC-IV were administered using laptop computers.

Sleep Deprivation

The DISC-IV does not inquire about symptoms of insomnia other than in the context of other DSM-IV disorders (such as mood or anxiety disorders). To supplement the DISC-IV, we inquired about symptoms of disturbed sleep, focusing primarily on symptoms of insomnia, their frequency and duration. Two questions inquired about hours of sleep on average the subject experienced on weeknights during the past 4 weeks and also on weekend nights. Six hours or less was defined as short sleep duration or deprivation,3,23,41 following the lead of earlier studies. That is, short sleep was defined 2 ways: ≤ 6 h only on weeknights and ≤ 6 h on both weeknights and weekend nights. The sleep items were taken from a variety of validated sleep questionnaires, including SleepEVAL.42,45

Covariates

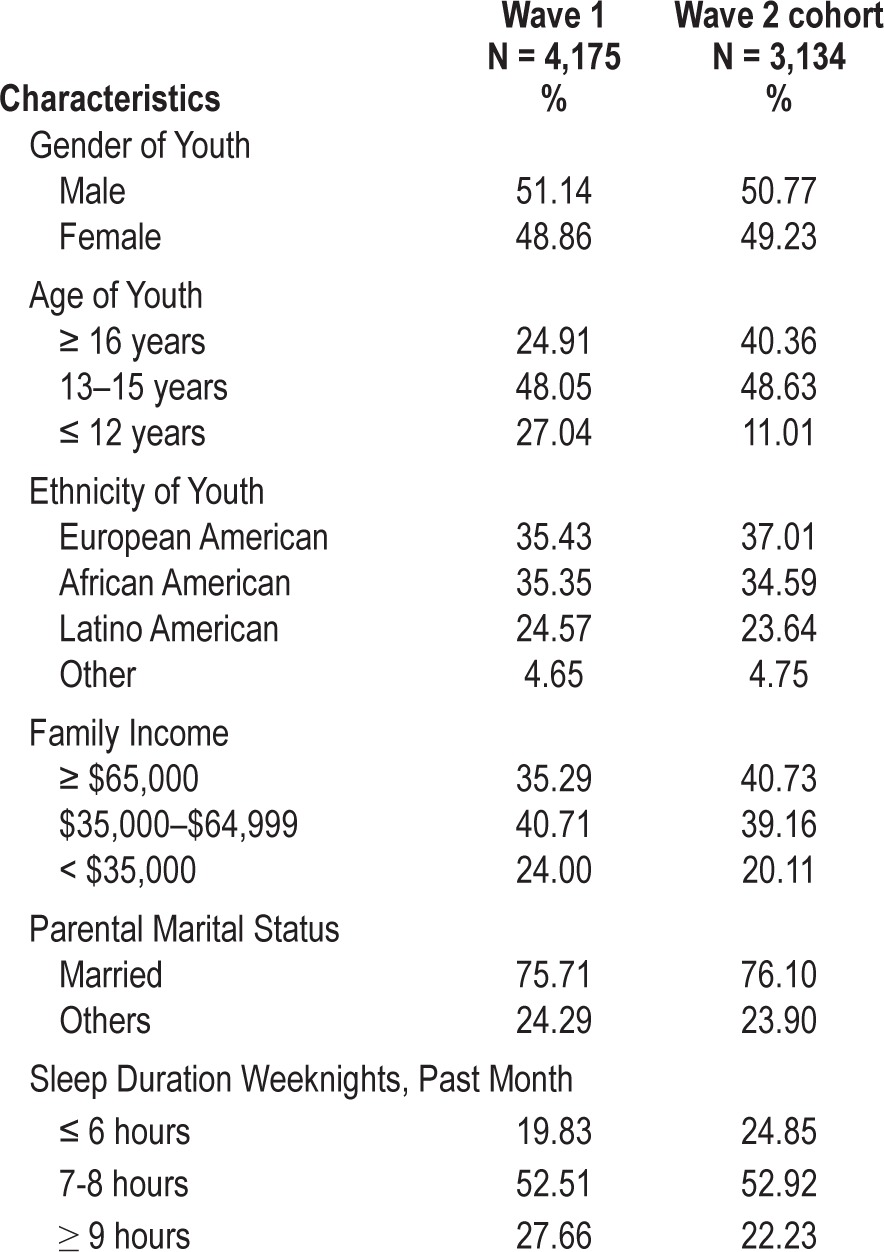

We include as covariates known correlates of both depression and sleep: age, gender, and family income. Family income was assessed using total household income in the past year: < $35,000, $35,000 - $64,999, and $65,000 or more. Age was assessed by age at most recent birthdate: 12 or less, 13-15, and 16 or older. Table 1 presents characteristics of the sample and cohort. As can be seen, the sample is diverse. In terms of hours of sleep, about 20% slept ≤ 6 h on weeknights. About 9% slept ≤ 6 h every night.

Table 1.

Unweighted sample characteristics, Teen Health 2000 sample and cohort

Analyses

First, the relationship between sleep deprivation on week-nights or both weeknights and weekends and depression (yes, no) at Wave 1 was examined, calculating crude odds ratios and then adjusted odds ratios controlling for age, gender, and family income. Second, sleep deprivation at Wave 1 was used to predict depression at Wave 2, first examining crude odds ratios and then adjusted odds ratios controlling for the same covariates. We also controlled for depression at baseline, either major depression or symptoms, depending on the focus. We then repeated this strategy using depression at Wave 1 to predict sleep deprivation at Wave 2, controlling for sleep at Wave 1.

The estimated odds ratios and their 95% confidence limits were calculated using survey logistic regression (Proc Survey-logistic) procedures in SAS V9.146 and Taylor series approximation to compute the standard error of the odds ratio. Lepkowski and Bowles47 have indicated that the difference in computing standard error between this method and other repeated replication methods such as the jackknife is very small.

RESULTS

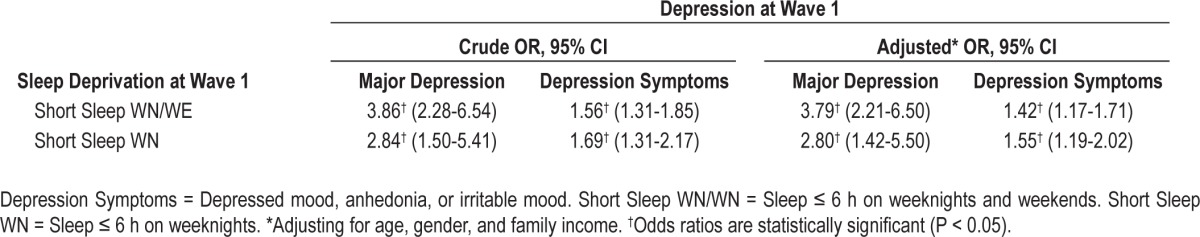

Table 2 presents results for the association between sleep deprivation and depression at baseline. Short sleep consistently was associated with depression, both major depression and depressive symptoms, although the effect was less robust for symptoms.

Table 2.

Odds ratios for the association between sleep deprivation and depression at Wave 1

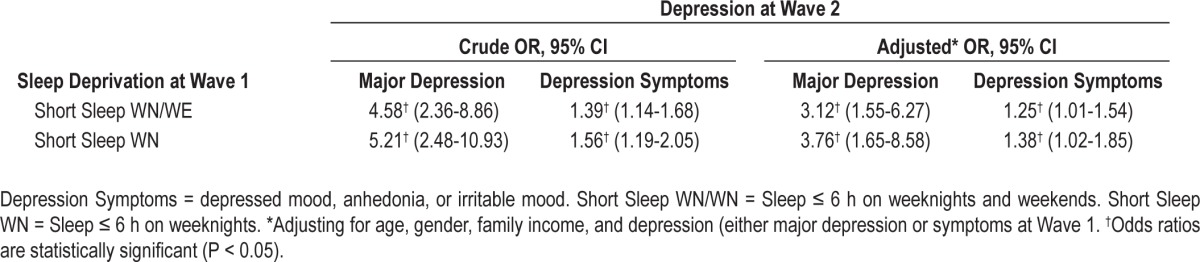

In Table 3, the same prospective association was observed for sleep deprivation and both measures of depression. Adjustment for covariates affects the associations, but all were still significant (P < 0.05). Again, the effect is stronger for major depression than for symptoms.

Table 3.

Odds ratios for the association between sleep deprivation at Wave 1 and depression at Wave 2

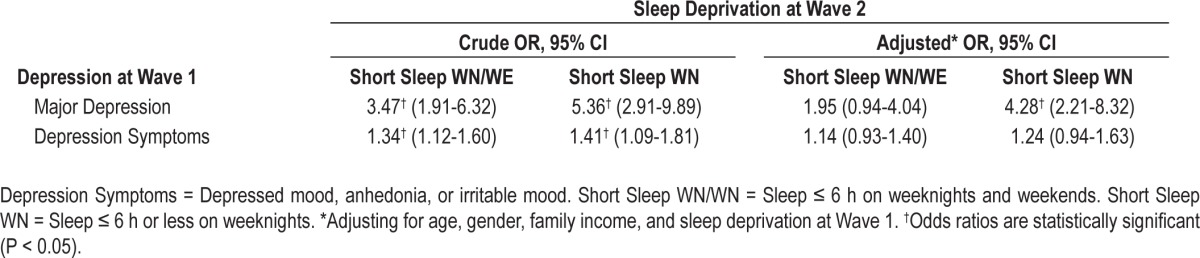

When we examined the reverse prospective association in Table 4, there was increased risk for short sleep among those depressed at baseline. However, after controlling for covariates, only one association remained significant—major depression at baseline increased risk of sleep deprivation only on weeknights.

Table 4.

Odds ratios for the association between depression at Wave 1 and sleep deprivation at Wave 2

DISCUSSION

We found that sleep deprivation, defined as 6 hours or less on weeknights and every night (including weekends) and symptoms of depression covary at baseline. In this regard, our results are consistent with the literature, which largely is based on cross-sectional research. When we examined whether sleep deprivation at baseline increased risk of depressive symptoms at follow-up, we found a 25% to 38% increased risk. This is similar to previous studies.23,24,27

However, when we looked at reciprocal effects, depressive symptoms predicting sleep deprivation, we found no association. Similar results have been reported for insomnia among youths35 as well as for depressed mood.13 The latter paper was based on the same data used here, Teen Health 2000.

When we turned to the association between sleep deprivation and major depression, we found the two were correlated at baseline. We also found that baseline sleep deprivation increased risk for subsequent major depression, by a factor of more than 3. This association was much stronger than for depressive symptoms, as noted above. When we examined the reciprocal association, controlling for covariates, the odds were 1.95 (n.s.) for sleep deprivation every night, but 4.28 (P < 0.05) for sleep deprivation on weeknights. While not statistically significant, an odds of almost 2 is not trivial, but power is problematic given the low prevalence of major depression.

Limitations

As noted earlier, our sleep items asked whether subjects had experienced symptoms almost every day for the past 4 weeks. Therefore, our results are limited, in that we could not date onset and thus were not able to partition our sample into those with acute versus long-term sleep deprivation. In a recent paper, Buysse et al.48 found differential results related to duration of insomnia among young adults. In their epidemiologic study in the United Kingdom, Ohayon et al.49 found that the median duration of insomnia symptoms was 24 months. We could not examine whether risk-factor profiles differed for those with sleep disturbance of shorter and longer duration (> 24 months), although it might be expected that the association with somatic, psychological, and interpersonal functioning would be pronounced for chronic sleep problems of longer duration.

Another limitation is that we did not have objective data on disturbed sleep. That is, we did not have physiologic studies. While such data would be useful to have, self-reports and interview-based measures remain the measures of choice in community surveys. Our study was no exception. We should note that there are data suggesting that subjective measures of sleep from children and adolescents are modestly correlated with objective measures of disturbed sleep.50 We should note as well that the use of laboratory measures are impractical in large field studies such as TH2K.5,7 We should note that studies have shown that youths with MDD report subjective sleep disturbance that is not accompanied by objective indicators of disturbed sleep.51

We also should note that although our sleep assessment inquired about symptoms experienced in the past 4 weeks, this involved retrospective recall. Use of sleep diaries would have provided daily data on sleep symptoms, but are difficult to employ in large, community-based epidemiologic surveys such as TH2K.

Questions might arise about our sample design. We did not employ an area probability design. To compensate for this design effect, we post-stratified our sample to approximate the age, gender, and ethnic composition of the population 11 to 17 years. Our weighted sample closely approximated the age, gender, and ethnic composition of the five-county metropolitan area. Our follow-up rate was 75%, which raises the issue of potential bias. However, in a previous paper,43 data demonstrated our Wave 1 sample and the baseline data for the Wave 1 – Wave 2 cohort were highly comparable, indicating little bias in rates of psychiatric disorders including depression was introduced by attrition. There also was no bias evident in prevalence rates for short sleep in Wave 1 and 2.

We also did not interview parents about either sleep disturbance or depression in their adolescents. Although there is argument that data from multiple informants are desirable, many studies have demonstrated considerable discordance is parent-child reports of youth problems.52,53 We used data only from youths.

CONCLUSIONS

We are the first to examine the prospective association between sleep deprivation and major depression in adolescents. We also are the first to directly investigate whether there is a reciprocal effect.

We find that sleep deprivation has a strong effect on risk for major depression, increasing risk 4- to 5-fold in crude analyses and 3-fold in multivariate analyses controlling for depression at baseline. Sleep deprivation also increased risk of depressive symptoms, but the effect, while significant, was greatly attenuated compared to major depression.

When we examined the reverse, the results were quite different. There was no increased risk of sleep deprivation among those with depressive symptoms. There was an effect for major depression but this was limited to sleep deprivation only on weeknights. It may be that since major depression impairs functioning in multiple life domains,40 and the combination of phase delay, late night activities or jobs and early morning school demands during weekdays and weeknights12,14,17 further restrict sleep, that this explains in part this association.

These results, particularly for major depression, suggest that quantity of sleep, following DSM-IV guidelines40 increases risk for major depression, which in turn increases risk for decreased sleep. This is not surprising, given the phenomenology of both sleep disturbances and major depression. DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for major depression focus on insomnia (insufficient sleep) or hypersomnia (sleeping too much), hence enhancing the likelihood of major depression increasing subsequent risk of short sleep duration.

Our results extend the available data on sleep and depression and are the first prospective data on this question. Clearly more data are needed on the prospective reciprocal association between these major public health problems in adolescence. In particular, our results need to be replicated in different geographic and ethnocultural populations in the United States as well as cross-nationally. While our results for sleep and psychiatric disorder8,24 appear comparable to other studies, the sample was drawn from one large metropolitan area in the Southwest, and generalizability or external validity is always a concern. What is needed as well are studies which examine developmental trajectories of sleep and depression from childhood through adolescence into adulthood.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. This research was supported, in part, by Grants Nos. MH 49764 and MH 65606 from the National Institutes of Health awarded to the first author, by the Michael and Susan Dell Center for Healthy Living, and by the University of Texas. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge Catherine R. Roberts, PhD, at the University of Texas School of Medicine (retired), for assistance in the design and conduct of the study and collection and management of the data.

REFERENCES

- 1.Carskadon MA, Acebo C, Jenni OG. Regulation of adolescent sleep: implications for behavior. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1021:276–91. doi: 10.1196/annals.1308.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carskadon MA. Patterns of sleep and sleepiness in adolescents. Pediatrician. 1990;17:5–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gau SF, Soong WT. Sleep problems of junior high school students in Taipei. Sleep. 1995;18:667–73. doi: 10.1093/sleep/18.8.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson EO, Roth T, Breslau N. The association of insomnia with anxiety disorders and depression: exploration of the direction of risk. J Psychiatr Res. 2006;40:700–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu X, Uchiyama M, Okawa M, Kurita H. Prevalence and correlates of self-reported sleep problems among Chinese adolescents. Sleep. 2000;23:27–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morrison DN, McGee R, Stanton WR. Sleep problems in adolescence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1992;31:94–9. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199201000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohayon MM, Roberts RE, Zulley J, Smirne S, Priest RG. Prevalence and patterns of problematic sleep among older adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:1549–56. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200012000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roberts RE, Roberts CR, Chan W. Ethnic differences in symptoms of insomnia among adolescents. Sleep. 2006;29:359–65. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.3.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberts CR, Roberts RE, Chen IG. Prevalence and correlates of peer victimization in a sample of U.S. adolescents aged 11-17. In: Westphal MR, editor. Violence and children. Sao Paulo: Federal University of Sao Paulo; 2002. pp. 207–47. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terman LM, Hocking A. The sleep of school children: its distribution according to age, and its relation to physical and mental efficiency. J Educational Psychology. 1913;4:138–47. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tynjala J, Kannas L, Valimaa R. How young Europeans sleep. Health Educ Res. 1993;8:69–80. doi: 10.1093/her/8.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolfson AR, Carskadon MA. Sleep schedules and daytime functioning in adolescents. Child Dev. 1998;69:875–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberts RE, Roberts CR, Xing Y. Restricted sleep among adolescents: Prevalence, incidence, persistence, and associated factors. Behav Sleep Med. 2011;9:18–30. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2011.533991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carskadon MA. Factors influencing sleep patterns of adolescents. In: Carskadon MA, editor. Adolescent sleep patterns: biological, social, and psychological influences. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2002. pp. 4–26. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colten HR, Altevogt BM. Sleep disorders and sleep deprivation: an unmet public health problem. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, Institute of Medicine; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolfson AR. Sleeping patterns of children and adolescents: Developmental trends, disruptions, and adaptations. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 1996;5:549–68. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolfson AR. Bridging the gap between research and practice: what will adolescents' sleep-wake patterns look like in the 21 century? In: Carksadon MA, editor. Adolescent sleep patterns: Biological, social, and psychological influences. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2002. pp. 198–219. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carskadon MA. The second decade. In: Guilleminault C, editor. Sleeping and waking disorders: Indications and techniques. Menlo Park, CA: Addison-Wesley; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carskadon MA, Dement WC. Distribution of REM sleep on a 90 minute sleep-wake schedule. Sleep. 1980;2:309–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carskadon MA, Orav EJ, Dement WC. New York: Raven Press; 1983. Evolution of sleep and daytime sleepiness in adolescents. Sleep/wake disorders: Natural history, epidemiology, and long-term evolution. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dahl RE, Lewin DS. Pathways to adolescent health sleep regulation and behavior. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31:175–84. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00506-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Millman RP Working Group on Sleepiness in Adolescents/Young Adults, AAP Committee on Adolescence. Excessive sleepiness in adolescents and young adults: causes, consequences, and treatment strategies. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1774–86. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fredriksen K, Rhodes J, Reddy R, Way N. Sleepless in Chicago: tracking the effects of adolescent sleep loss during the middle school years. Child Dev. 2004;75:84–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roberts RE, Roberts CR, Chan WY. One-year incidence of psychiatric disorders and associated risk factors among adolescents in the community. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009;50:405–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roberts RE, Roberts CR, Chen IG. Functioning of adolescents with symptoms of disturbed sleep. J Youth Adolesc. 2001;30:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gregory AM, O'Connor TG. Sleep problems in childhood: a longitudinal study of developmental change and association with behavioral problems. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:964–71. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200208000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gangwisch JE, Malaspina D, Babiss LA, et al. Short sleep duration as a risk factor for hypercholesterolemia: analyses of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Sleep. 2010;33:956–61. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.7.956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yen CF, Ko CH, Yen JY, Cheng CP. The multidimensional correlates associated with short nocturnal sleep duration and subjective insomnia among Taiwanese adolescents. Sleep. 2008;31:1515. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.11.1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glozier N, Martiniuk A, Patton G, et al. Short sleep duration in prevalent and persistent psychological distress in young adults: the DRIVE study. Sleep. 2010;33:1139. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.9.1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ford DE, Kamerow DB. Epidemiologic study of sleep disturbances and psychiatric disorders. An opportunity for prevention? JAMA. 1989;262:1479–84. doi: 10.1001/jama.262.11.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vollrath M, Wicki W, Angst J. The Zurich study. VIII. Insomnia: association with depression, anxiety, somatic syndromes, and course of insomnia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Neurol Sci. 1989;239:113–24. doi: 10.1007/BF01759584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Breslau N, Roth T, Rosenthal L, Andreski P. Sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders: A longitudinal epidemiological study of young adults. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;39:411–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00188-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ohayon MM, Roth T. Place of chronic insomnia in the course of depressive and anxiety disorders. J Psychiatr Res. 2003;37:9–15. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(02)00052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buysse DJ, Angst J, Gamma A, Ajdacic V, Eich D, Rössier W. Prevalence, course, and comorbidity of insomnia and depression in young adult. Sleep. 2008;31:473–80. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.4.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson EO, Roth T, Schultz L, Breslau N. Epidemiology of DSM-IV insomnia in adolescence: lifetime prevalence, chronicity, and an emergent gender difference. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e247–56. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lui X, Buysse DJ, Gentzier AL, et al. Insomnia and hypersomnia associated with depressive phenomenology and comorbidity in childhood depression. Sleep. 2007;30:83–90. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gehrman PR, Meltzer LJ, Moore M, et al. Ratability of insomnia symptoms in youth and their relationship to depression and anxiety. Sleep. 2011;34:1641–6. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roberts RE, Duong HT. Perceived weight, not obesity, increases risk for major depression among adolescents. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47:1110–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Andrews FF, Morgan JN. Multiple classification analysis. In: Andrews FF, Morgan JN, editors. Multiple classification analysis: a report on a computer program for multiple regression using categorical predictors. 2nd ed. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 40.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. text revision. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Angold A, Erkanli A, Copeland W, Goodman R, Fisher PW, Costello EJ. Psychiatric diagnostic interviews for children and adolescents: A comparative study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51:506–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone ME. NIMH diagnostic interview schedule for children version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): Description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roberts RE, Roberts CR, Duong HT. Sleepless in adolescence: Prospective data on sleep deprivation, health and functioning. J Adolesc. 2009;32:1045–57. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ohayon MM, Roberts RE. Comparability of sleep disorders diagnoses using DSM-IV and ICSD classifications with adolescents. Sleep. 2001;24:920–5. doi: 10.1093/sleep/24.8.920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ohayon MM, Roberts RE, Zulley J, Smirne S, Priest RG. Prevalence and patterns of problematic sleep among older adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:1549–56. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200012000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.SAS Institute. SAS/STAT 9.1: User's guide. Cary, NC: SAS Pub; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lepkowski J, Bowles J. Sampling error software for personal computers. The Survey Statistician. 1996;35:10–7. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Buysse DJ, Angst J, Gamma A, Ajdacic V, Eich D, Rossler W. Prevalence, course, and comorbidity of insomnia and depression in young adults. Sleep. 2007;31:473–80. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.4.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ohayon MM, Caulet M, Priest RG, Guilleminault C. DSM-IV and ICSD-90 insomnia symptoms and sleep dissatisfaction. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171:382–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.171.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sadeh A, McGuire JP, Sachs H, et al. Sleep and psychological characteristics of children on a psychiatric inpatient unit. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34:813–9. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199506000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Forbes EE, Bertocci MA, Gregory AM, et al. Objective sleep in pediatric anxiety disorders and major depressive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47:148–55. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31815cd9bc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roberts RE, Alegria M, Roberts CR, Chen IG. Concordance of reports of mental health functioning by adolescents and their caregivers: a comparison of European, African and Latino Americans. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2005;193:528–34. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000172597.15314.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Roberts RE, Alegría M, Roberts CR, Chen IG. Mental health problems of adolescents as reported by their caregivers. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2005;32:1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]