Abstract

Study Objective:

The association between restless legs syndrome (RLS) and Parkinson disease has been extensively studied, but the temporal relationship between the two remains unclear. We thus conduct the first prospective study to examine the risk of developing Parkinson disease in RLS.

Design:

Prospective study from 2002-2010.

Setting:

United States.

Participants:

There were 22,999 US male health professionals age 40-75 y enrolled in the Health Professionals Follow-up Study without Parkinson disease, arthritis, or diabetes mellitus at baseline.

Measurement and Results:

RLS was assessed in 2002 using a set of standardized questions recommended by the International RLS Study Group. Incident Parkinson disease was identified by biennial questionnaires and then confirmed by review of participants' medical records by a movement disorder specialist. We documented 200 incident Parkinson disease cases during 8 y of follow-up. Compared to men without RLS, men with RLS symptoms who had symptoms greater than 15 times/mo had higher risk of Parkinson disease development (adjusted relative risk = 1.47; 95% confidence interval: 0.59, 3.65; P = 0.41). This was statistically significant only for cases diagnosed within 4 y of follow-up (adjusted relative risk = 2.77; 95% confidence interval: 1.08, 7.11; P = 0.03).

Conclusion:

Severe restless legs syndrome may be an early feature of Parkinson disease.

Citation:

Wong JC; Li Y; Schwarzschild MA; Ascherio A; Gao X. Restless legs syndrome: an early clinical feature of Parkinson disease in men. SLEEP 2014;37(2):369-372.

Keywords: Restless legs syndrome, Parkinson disease, prospective study

INTRODUCTION

The association between restless legs syndrome (RLS) and Parkinson disease (PD) has been extensively discussed.1–9 For example, in our recent cross-sectional study of a large cohort of 23,119 men in the Health Professional Follow-up Study (HPFS), men with RLS had a higher prevalence of PD than men without RLS.10 However, the temporal relationship between RLS and PD remained unclear. In studies that relied on participants' ability to accurately recall onset of symptoms, RLS symptoms appeared before the onset of PD in some participants: in one study, 33 of 87 patients with PD and RLS developed RLS before PD,11 and in another study, 5 of 28 patients with idiopathic PD and RLS developed RLS before PD.12 In a study conducted by Walters et al.,13 4 of 85 patients referred for RLS developed PD after RLS onset, which was higher than the ∼1% prevalence of PD in the general population age 60 y or older. However, these studies were cross-sectional or retrospective and thus subject to recall bias. To our knowledge, no study followed a large cohort prospectively to determine the development of PD after the onset of RLS. This was likely due to the challenge of constructing a cohort large enough to capture development of PD in established cases of RLS. Thus, the purpose of the current study was to prospectively analyze the risk of PD development in men with RLS compared to men without RLS from the HPFS cohort, within an 8-y follow-up period (2002-2010), as well as the initial 4-y follow-up period (2002-2006).

METHODS

This study was a prospective longitudinal cohort study. The study population, assessment of RLS, PD, and covariates had previously been described.10 The HPFS is a prospective cohort study of heart disease and cancer among male professionals (dentists, optometrists, pharmacists, podiatrists, and veterinarians) residing in the United States. The study began in 1986 when 51,529 of these health professionals, age 40-75 y, answered a detailed mailed questionnaire that included a comprehensive diet survey, items on lifestyle practices, and medical history. The cohort has been followed by means of biennial mailed questionnaires, which inquire about lifestyle practices and other exposures of interest, as well as the incidence of disease.

Three RLS questions based on International RLS Study Group (IRLSSG) criteria were asked and completed by 31,729 men in 2002.10 The following question was asked: “Do you have unpleasant leg sensations (like crawling, paraesthesia, or pain) combined with motor restlessness and an urge to move?” The possible responses were as follows: no; less than once/mo; 2-4 times/mo; 5-14 times/mo; and 15 or more times per mo. Those who answered that they had these feelings were asked the following two questions: (1) “Do these symptoms occur only at rest and does moving improve them?”; and (2) “Are these symptoms worse in the evening/night compared with the morning?” A participant who reported symptoms five or more times per mo and answered yes to all the three questions was considered to have RLS.10

In the current analysis, we excluded men with PD at the baseline (2002). Men with diabetes and arthritis—common mimics of RLS—were also excluded due to concerns of possible misclassification of RLS, leaving 22,999 men in analysis. In a study of 369 German participants age 65-83 y, sensitivity, specificity, and kappa statistic of the RLS three-question set used in the current study were 87.5%, 96%, and 0.67, respectively, compared with physician diagnoses.14,15

We identified new PD cases by biennial self-reported questionnaires.16,17 We then asked the treating neurologists to send a copy of the medical records. A movement disorder specialist who was blind to the exposure status reviewed medical records. A case was confirmed if a diagnosis of PD was considered definite or if the medical record included evidence of at least two of the three cardinal signs (rest tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia) in the absence of features suggesting other diagnoses. We also requested the death certificates of the deceased study participants and identified PD diagnoses that were not reported in the regular follow-up (less than 2%). If PD was listed as a cause of death on the death certificate, we requested permission from the family to contact the treating neurologist or physician and followed the same procedure as for the nonfatal cases. This study was approved by the institutional review board at Brigham and Women's Hospital. Consent from participants was implied by submission of their questionnaires.

Statistical analysis was performed with SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC). We computed the person-time of follow-up for each participant from the return date of the baseline questionnaire (2002) to the date of the occurrence of the first symptoms of PD, the date of death, or the end of follow up (2010), whichever came first. Participants were divided into three categories based on frequency of RLS symptoms at baseline in 2002 (no RLS, RLS symptoms 5-14 times per mo, RLS symptoms 15 times or more per mo).10 For each category of baseline RLS status, relative risks (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated with a Cox proportional hazards model for development of PD from 2002-2010, as well as during the first 4 y of follow-up (2002-2006). RR values were adjusted for age (< 60, 60-64, 65-69, 70-74, 75-79 or ≥ 80 y old), smoking status (never smoker, former smoker, or current smoker: cigarettes per day, 1-14 or ≥ 15), alcohol intake (0,0.1-9.9, 10.0-19.9, 20.0-29.9, or ≥ 30 g per day), consumption of caffeine (quintiles), and lactose (quintiles), body mass index (< 23, 23-24.9, 25-26.9, 27-29.9, or ≥ 30 kg/m2), physical activity (quintiles), and use of antidepressants (yes or no, a surrogate of depression). We used missing values indicators for individuals missing information on one covariate, so that each model included the same number of individuals. Interactions between RLS and age (y), smoking (ever versus never) and caffeine intake (low versus high, based on median value) were also analyzed for potential modification effects, by including multiplicative terms in the multivariate models.

RESULTS

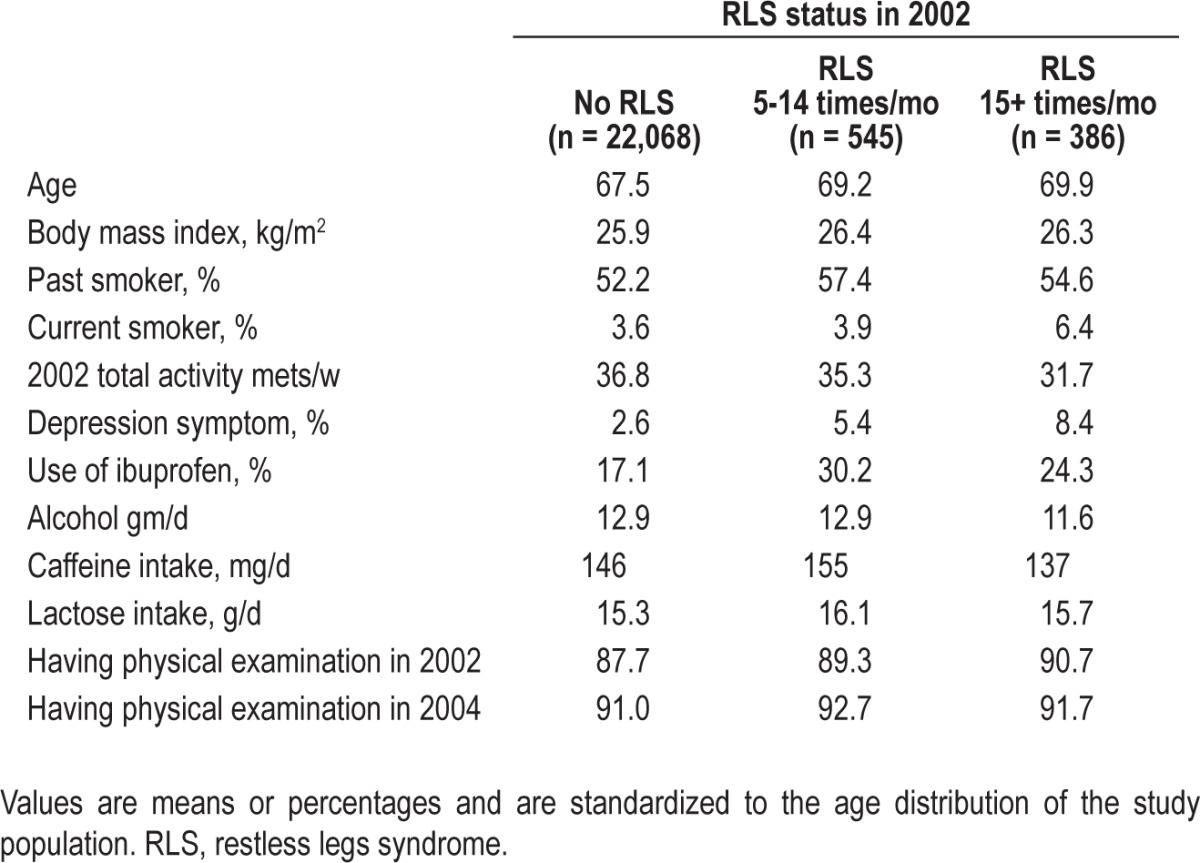

At baseline in 2002, men with RLS were older and more likely to be past or current smokers, use ibuprofen, and undergo physical examination because of symptoms. Men with RLS also had higher body mass index, lower levels of activity, and higher rates of depression (Table 1). From 2002-2010, 200 new cases of PD were documented in the cohort. Notably, among 931 men with RLS at baseline, seven of eight incident PD cases were identified during the first 4 y of follow-up.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics according to restless legs syndrome status in 2002 in the Health Professionals Follow-up Study

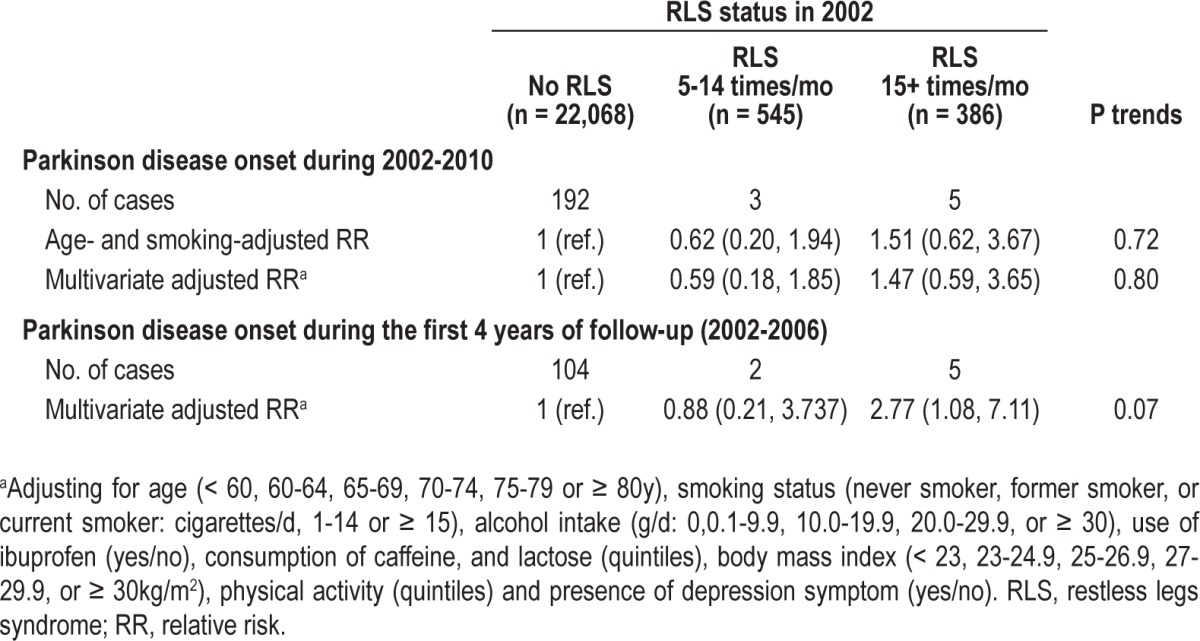

Compared to men without RLS, men with severe RLS (i.e., RLS symptom 15+ times/mo) had a nonsignificant increased risk of developing PD, after adjusting for age, smoking, and other potential covariates (Table 2). This association was significant (adjusted RR = 2.77; 95% CI: 1.08, 7.11; P = 0.03) when analysis was limited to the first 4 y of follow-up from 2002-2006. The association between severe RLS and elevated PD risk during the first 4 y of follow-up did not materially change after excluding men with depression symptoms (adjusted RR = 2.95; 95% CI: 1.14, 7.60; P = 0.03). The association between severe RLS and elevated PD risk during the first 4 y of follow-up was also significant after excluding men with use of H2 blockers (adjusted RR = 2.88; 95% CI: 1.11, 7.49; P = 0.05), which has been suggested to be associated with RLS risk.18

Table 2.

Relative risks and 95% confidence interval of Parkinson disease according to baseline restless legs syndrome status in the Health Professionals Follow-up Study

Due to concern about the possibility that men with severe RLS at baseline might have visited their physicians more frequently and thus were more likely to be found to have PD, we further adjusted for having physical examination at baseline and in the first 2 y of follow-up. The association between severe RLS and risk of PD during the first 4 y of follow-up was attenuated slightly but remained significant (adjusted RR = 2.67; 95% CI: 1.03, 6.88; P = 0.04). Interactions between RLS and age, smoking, and caffeine intake were not significant (P > 0.2 for all).

DISCUSSION

The presence of RLS symptoms was associated with higher risk of PD development during the first 4 y of follow-up, but this finding was only statistically significant in cases with more severe RLS symptoms of 15 or more times per mo. The significantly increased risk of PD development in RLS was observed in the first 4 y—but not full 8 y—of follow-up, suggesting that RLS was an early clinical feature of PD, not a risk factor. If RLS were a risk factor for PD, a longer period of follow-up— and hence greater exposure to the risk factor—would be expected to be associated with higher risk of PD development. Thus, RLS may be considered an early feature of PD, and may have a pathogenesis distinct from idiopathic RLS.

Current data support the hypothesis that RLS in PD is a different entity from idiopathic RLS. Compared to idiopathic RLS, RLS-PD is associated with onset of RLS in older individuals,19 lower likelihood of a family history of idiopathic RLS,19 lower periodic limb movement index,19 higher IRLSSG severity scale scores, and lower ferritin levels.11 On sonography, idiopathic RLS has substantia nigra hypoechogenicity, while RLS-PD has substantia nigra hyperechogeneity like other PD cases.20 Studies also suggest that the presence of RLS in PD modifies the course of disease in PD: RLS is associated with presence of depression, more severe disability and cognitive decline among patients with PD.21,22

It is interesting to consider how RLS may fit into models of PD development, such as the Braak staging system that predicts synuclein pathology in the nondopaminergic structures of the lower brainstem in early PD; however, this staging system, as well as the anatomical substrates responsible for RLS, remain under debate.23 RLS is thought to have a dopaminergic mechanism that has yet to be elucidated,1–9 but the association of RLS severity with the severity of non-dopaminergic symptoms in PD, such as cognitive, autonomic, mood, or psychotic disorders, raises the possibility of a concurrent nondopaminergic mechanism in RLS.24

This study had several limitations. There were few new PD cases that developed in participants with RLS, so lack of power may explain why statistical significance was not reached when comparing the risk of PD development in all cases of RLS, including the mild cases, and cases of no RLS. This study was limited to men, so it could not be generalized to women. In addition, assessment of RLS was based on self-report, without verification by physical examination. Nevertheless, there is a high correlation of self-reported measures of RLS and doctor diagnoses in previous validation studies.14,15 Although we excluded two common RLS mimics— diabetes mellitus (a surrogate of peripheral neuropathy) and arthritis—in our primary analysis, we did not exclude other RLS mimics such as other causes of peripheral neuropathy, use of antipsychotics, akasthesia, or degenerative spine disease because we did not collect relevant information in the HPFS. This could have resulted in an overestimation of RLS. Because there is no evidence that RLS mimics are associated with increased risk of PD, misclassification of RLS assessment could have lead to an underestimation of the association between RLS and PD risk.

In conclusion, men with severe RLS were at higher risk of developing PD within 4 y of follow-up, suggesting that RLS could be an early clinical feature of PD. It will be interesting to investigate the pathological basis of RLS development in the context of PD staging in future studies.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. This study was supported by grants (P01 CA055075, R01 NS048517, and R01 NS061858) from the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Gao had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest. Dr. Wong is now affiliated with the Department of Neurology, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA; Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA; Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tan EK. Restless legs syndrome and Parkinson's disease: is there an etiologic link? J Neurol. 2006;253:VII33–7. doi: 10.1007/s00415-006-7008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yeh P, Walters AS, Tsuang JW. Restless legs syndrome: a comprehensive overview on its epidemiology, risk factors, and treatment. Sleep Breath. 2012;16:987–1007. doi: 10.1007/s11325-011-0606-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moller JC, Unger M, Stiasny-Kolster K, Oertel WH. Restless legs syndrome (RLS) and Parkinson's disease (PD)—related disorders or different entities? J Neurol Sci. 2010;289:135–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2009.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iranzo A, Comella CL, Santamaria J, Oertel W. Restless legs syndrome in Parkinson's disease and other neurodegenerative diseases of the central nervous system. Mov Disord. 2007;22:S424–30. doi: 10.1002/mds.21600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poewe W, Hogl B. Akathisia, restless legs and periodic limb movements in sleep in Parkinson's disease. Neurology. 2004;63:S12–6. doi: 10.1212/wnl.63.8_suppl_3.s12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rye DB. Parkinson's disease and RLS: the dopaminergic bridge. Sleep Med. 2004;5:317–28. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2004.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garcia-Borreguero D, Odin P, Serrano C. Restless legs syndrome and PD: a review of the evidence for a possible association. Neurology. 2003;61:S49–55. doi: 10.1212/wnl.61.6_suppl_3.s49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Happe S, Trenkwalder C. Movement disorders in sleep: Parkinson's disease and restless legs syndrome. Biomed Tech (Berl) 2003;48:62–7. doi: 10.1515/bmte.2003.48.3.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lang AE. Restless legs syndrome and Parkinson's disease: insights into pathophysiology. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1987;10:476–8. doi: 10.1097/00002826-198710000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao X, Schwarzschild MA, O'Reilly EJ, Wang H, Ascherio A. Restless legs syndrome and Parkinson's disease in men. Mov Disord. 2010;(25):2654–7. doi: 10.1002/mds.23256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ondo WG, Vuong KD, Jankovic J. Exploring the relationship between Parkinson disease and restless legs syndrome. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:421–4. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.3.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peralta CM, Frauscher B, Seppi K, et al. Restless legs syndrome in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2009;24:2076–80. doi: 10.1002/mds.22694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walters AS, LeBrocq C, Passi V, et al. A preliminary look at the percentage of patients with restless legs syndrome who also have Parkinson disease, essential tremor or Tourette syndrome in a single practice. J Sleep Res. 2003;12:343–5. doi: 10.1046/j.0962-1105.2003.00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allen RP, Picchietti D, Hening WA, Trenkwalder C, Walters AS, Montplaisi J. Restless legs syndrome: diagnostic criteria, special considerations, and epidemiology. A report from the restless legs syndrome diagnosis and epidemiology workshop at the National Institutes of Health. Sleep Med. 2003;4:101–19. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(03)00010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berger K, von Eckardstein A, Trenkwalder C, Rothdach A, Junker R, Weiland SK. Iron metabolism and the risk of restless legs syndrome in an elderly general population--the MEMO-Study. J Neurol. 2002;249:1195–9. doi: 10.1007/s00415-002-0805-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao X, Chen H, Schwarzschild MA, Ascherio A. Use of ibuprofen and risk of Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2011;76:863–9. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31820f2d79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao X, Cassidy A, Schwarzschild MA, Rimm EB, Ascherio A. Habitual intake of dietary flavonoids and risk of Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2012;78:1138–45. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31824f7fc4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Sullivan RL, Greenberg DB. H2 antagonists, restless leg syndrome, and movement disorders. Psychosomatics. 1993;34:530–2. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(93)71830-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nomura T, Inoue Y, Nakashima K. Clinical characteristics of Restless legs syndrome in patients with Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Sci. 2006;250:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2006.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwon DY, Seo WK, Yoon HK, Park MH, Koh SB, Park KW. Transcranial brain sonography in Parkinson's disease with restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord. 2010;25:1373–8. doi: 10.1002/mds.23066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee JE, Shin HW, Kim KS, Sohn YH. Factors contributing to the development of restless legs syndrome in patients with Parkinson disease. Mov Disord. 2009;24:579–82. doi: 10.1002/mds.22410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krishnan PR, Bhatia M, Behari M. Restless legs syndrome in Parkinson's disease: a case-controlled study. Mov Disord. 2003;18:181–5. doi: 10.1002/mds.10307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burke RE, Dauer WT, Vonsattel JP. A critical evaluation of the Braak staging scheme for Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol. 2008;64:485–91. doi: 10.1002/ana.21541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Verbaan D, van Rooden SM, van Hilten JJ, Rijsman RM. Prevalence and clinical profile of restless legs syndrome in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2010;25:2142–7. doi: 10.1002/mds.23241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]