Abstract

Most breast abscesses develops as a complication of lactational mastitis. The incidence of breast abscess ranges from 0.4 to 11 % of all lactating mothers. The traditional management of breast abscesses involves incision and drainage of pus along with antistaphylococcal antibiotics, but this is associated with prolonged healing time, regular dressings, difficulty in breast feeding, and the possibility of milk fistula with unsatisfactory cosmetic outcome. It has recently been reported that breast abscesses can be treated by repeated needle aspirations and suction drainage. The predominance of Staphylococcus aureus allows a rational choice of antibiotic without having to wait for the results of bacteriological culture. Many antibiotics are secreted in milk, but penicillin, cephalosporins, and erythromycin, however, are considered safe. Where an abscess has formed, aspiration of the pus, preferably under ultrasound control, has now supplanted open surgery as the first line of treatment.

Keywords: Breast abscess, Mastitis, Breast feeding

Introduction

Most breast abscesses develop as a complication of lactational mastitis. The incidence of breast abscess ranges from 0.4 to 11 % of all lactating mothers [1]. Breast abscesses are more common in obese patients and smokers than in the general population [2]. The traditional management of breast abscess involves incision and drainage of pus along with antistaphylococcal antibiotics, but this is associated with prolonged healing time, regular dressings, difficulty in breastfeeding, and the possibility of milk fistula, and unsatisfactory cosmetic outcome [3]. It has recently been reported that breast abscesses can be treated by repeated needle aspirations and suction drainage [3]. The purpose of this article is to review the literature and lay down guidelines in the management of lactational mastitis and breast abscess.

Types of Breast Abscesses

Lactational Abscess

Risk factors for lactational breast abscess formation include the first pregnancy at maternal age over 30 years, pregnancy more than 41 weeks of gestation, and mastitis [2, 3]. It is relatively common for lactating women to develop a breast abscess as a complication of mastitis [1, 4] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Lactational abscesses

Nonlactational Abscesses

Nonlactational abscesses can be classified as central, peripheral, or skin associated. Patients with nonlactational abscesses, diabetics, and smokers are likely to develop recurrent infections. Central (periareolar) nonlactational abscesses are usually due to periductal mastitis [5].

Pathology and Bacteriology

The organism most commonly implicated is Staphylococcus aureus, which gains entry via a cracked nipple [6]. Occasionally, the infection is hematogenous. In the early stages, the infection tends to be confined to single segment of the breast, and it is relatively late that extension to other segments may occur. Milk provides an ideal culture medium, so bacterial dispersion in the vascular and distended segment is easy. The pathological process is identical to acute inflammation occurring elsewhere in the body, although the loose parenchyma of the lactating breast and the stagnant milk of an engorged segment allow the infection to spread rapidly both within the stroma and through the milk ducts, if unchecked. The bacteria are excreted in the milk. Benson and Goodman in a study found that majority of hospital-acquired infections were due to S. aureus, and of these, only 50 % had penicillin-sensitive organisms [6]. Breast abscess associated with methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) has been reported and is likely to be an increasing problem. A wide variety of organisms may occasionally be encountered. Typhoid is a well-recognized cause of breast abscess in countries where this disease is common. This is a particularly important diagnosis to make because the organism is secreted in the milk.

Clinical Features

Nursing mothers are most vulnerable to breast abscess at two stages:

During the first month of lactation following the first pregnancy when due to inexperience and inadequate hygiene, the nipples are more likely to be damaged. During the first month after delivery, 85 % of lactational breast abscesses occur [7].

At weaning, when the breasts are more likely to become engorged, an additional factor after about 6 months is that the baby’s teeth increase the likelihood of nipple trauma.

The signs and symptoms of breast abscesses are the following:

Well-defined fluctuant lump in the affected breast

Pain in the affected breast

Redness, swelling, and tenderness in an area of the breast

Fever and malaise

Enlarged axillary lymph nodes

Management of Breast Abscess

Assessment

The clinical problem may be resolved into cellulitis without pus formation and abscess. The importance of an accurate assessment of the situation cannot be overemphasized. Surgery in the early cellulitic phase is unnecessarily destructive, and continued antibiotic therapy in the presence of an abscess may lead to tissue destruction by the disease process. Test-needle aspiration of the cellulitic area, preferably preceded by ultrasound examination, should be performed [8]. If ultrasound shows an abscess, the needle can be guided into the cavity. It is wrong to wait for the development of fluctuation and pointing before proceeding to drainage, because further destruction of the breast tissue will occur. Even if no pus is aspirated, the opportunity should be used to carry out bacteriological examination of the aspirated material. A useful bonus of this approach is that the rare case of inflammatory carcinoma may be diagnosed on the smear, thus avoiding operation in this difficult condition.

Treatment

Taylor and Way [8] clearly enunciated the principles of treatment: curtail infection and empty the breast. The methods of achieving this differ in the cellulitic and abscess stages.

General measures are listed as follows:

Analgesics

Breast support

Role of cold cabbage leaves

Breast emptying and continuation of breastfeeding

Antistaphylococcal antibiotics

Specific measures are listed as follows:

Aspiration of pus

- Ultrasonography (USG) guided

- Needle aspiration

- Catheter drainage

Incision and drainage

General Measures

Analgesics: Ibuprofen is regarded as most efficient, and it also helps to reduce inflammation and edema. Paracetamol can be used as an alternative. Tramadol and other opioids are avoided as they have central nervous system depressant effect on newborn.

Providing adequate breast support: Breast support garment helps in relaxing the stretched Cooper’s ligament, reducing the movement of painful organ and reducing edema.

-

Role of cabbage leaves: Women have been using cabbage leaves to relieve engorgement symptoms for centuries (Fig. 2). However, does this natural remedy actually work? Few research studies have been able to medically prove whether cabbage leaves actually alleviate engorgement.

Nikodem et al. [12] evaluated 120 breastfeeding women who were split into two groups: one group used cabbage leaves on their breasts to relieve engorgement, and the other group received “routine care.” The cabbage leaf group tended to report less engorgement, but the trend was not statistically significant. The researchers did find that the women who used cabbage leaves were more likely to be exclusively breastfeeding at 6 weeks than those who did not [9].

Roberts et al. compared the effectiveness of chilled and room-temperature cabbage leaves. Twenty-eight lactating women with breast engorgement used chilled cabbage leaves on one breast and room-temperature leaves on the other. After a 2-h period, the women reported significantly less pain with both treatments. The researchers concluded that it is not necessary to chill cabbage leaves before use [10].

In 2008, a study was conducted at maternity wards of All India Institutes of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, to assess and compare the efficacy of cold cabbage leaves and hot and cold compresses in the treatment of breast engorgement. The study comprised a total of 60 mothers: 30 in the experimental group and 30 in the control group. The control group received alternative hot and cold compresses, and the experimental group received cold cabbage leaf treatment for relieving breast engorgement. They concluded that both cold cabbage leaves as well as alternative hot and cold compresses were effective in the treatment of breast engorgement. Hot and cold compresses were reported to be more effective than cold cabbage leaves in relieving pain because of breast engorgement [11].

The following are the methods of using cabbage leaves:- Green ordinary cabbage is preferable.

- Cabbage leaves are not to be used if one has allergy or sensitivity to cabbage. Cabbage leaves should be immediately discontinued if a rash appears.

- The leaves should be washed thoroughly.

- The veins should be crushed or removed to allow the leaf to conform better to the shape of the breast.

- They can be chilled in the refrigerator as some studies show better control of pain and engorgement with the chilled leaf.

- The leaf should be placed inside a sport bra, wrapped around the breast with the nipple exposed for 2 h or until wilted.

- It should be checked whether the breasts are responding with each change, and use of the leaves should be stopped once engorgement is reduced.

-

Emptying the breast: This important aspect of the management of puerperal breast infection is sometimes ignored. The breast may be emptied either by suckling or by expression. Although bacteria are present in the milk, no harm appears to be done to the infant if breastfeeding is continued [13, 14]. After open surgical drainage of an abscess, suckling may be difficult for a few days because of pain of a cut and the dressing over the affected side, but the mother should be encouraged to feed on the unaffected side. The infected breast, however, should be emptied either by manual expression or by a pump.

Regular natural milk emptying of the breast is an essential part of the treatment. Breast emptying with mechanical devices is recommended only for a subareolar localization of the abscess, or when the drain or dressing placement renders natural feeding impossible. In such cases, mother can continue breastfeeding from the other breast, and the affected breast must be emptied mechanically. The milk from that breast may be given to the baby without pasteurization if it does not contain pus or blood. Such a procedure is also safe for the baby because mother’s milk provides immunological protection by the oral supply of specific antibody and immunocompetent cells acting against mother’s causative microbiologic agents [15]. There is consensus that lactation should be continued, allowing for proper drainage of ductolobular system of the breast. Continuing breastfeeding does not present any risk to the nursing infant [16–18].

Fig. 2.

Method of application of cabbage leaves

Suppression of Lactation

Drug-induced blockade of lactation dramatically affects the hormonal status of breastfeeding women, resulting in nausea, vomiting, and bad general feeling. All these symptoms lower the quality of life and may adversely affect mental state of patients. Drug-induced blockade of lactation is contraindicated because of its negative impact on the immune system as well as physical and mental development of the suckling baby [15]. If it is decided to abandon breastfeeding, lactation should be suppressed as quickly as possible. The most effective suppressant currently available is probably cabergolamine, which is effective as a single dose and so is preferable to bromocriptine 2.5 mg twice daily for 14 days [10]. The engorged breast should be emptied as far as possible mechanically. Fluid restriction and firm binding seem unnecessary.

Technique of breast emptying is presented as follows:

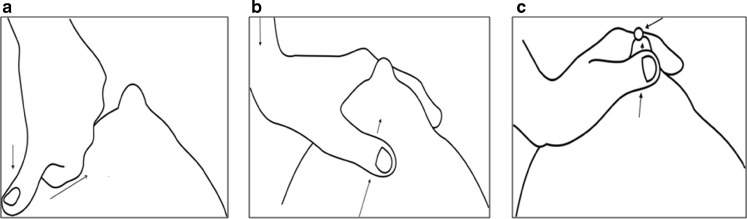

The breast distal to the area of mastitis is squeezed firmly between the thumb and the rib cage; then the thumb, with pressure maintained, is moved up to the areola (Fig. 3a).

With downward pressure maintained, the index finger is placed on the opposite side of the areola (Fig. 3b).

The pus is squeezed out between the thumb and the index finger (Fig. 3c).

-

5.

Role of oral and systemic antibiotics: Most cases of mastitis that progress to breast abscess involve infections with S. aureus. Though other infective organisms may cause mastitis, an antibiotic effective against penicillin-resistant staphylococci has been recommended to decrease the possibility of breast abscess.

Fig. 3.

Technique of breast emptying

Choice of Antibiotics

The choice of antibiotics should depend on following considerations:

Drug should be secreted and concentrated in good concentration in milk.

The drug should remain active in acidic pH of milk.

It should not harm the suckling baby.

The beta lactamase-resistant penicillins have been recommended in the treatment of mastitis. These include cloxacillin, dicloxacillin, or flucloxacillin. Because penicillins are acidic, they are poorly concentrated in human milk, which is also acid. Therefore, cloxacillin and its congeners tend to treat cellulitis well, but they are less effective in eradicating adenitis, the most likely precursor of breast abscess. Erythromycin, being alkaline, is well concentrated and remains active in human milk. Though some rare strains of staphylococci are resistant to erythromycin, this drug may be the best antibiotic in the treatment of adenitis of the breast, where the infection resides primarily in the milk ducts. Both cloxacillin and erythromycin can safely be given to infants, but erythromycin is less likely to trigger antibiotic-sensitivity reactions [20]. When patients are allergic to penicillins, cephalexin or clindamycin may be the alternative to erythromycin [21]. Combination like co-amoxiclav should be avoided because of fear of inducing MRSA (Table 1).

Table 1.

Antibiotics most appropriate for treating breast infections [21]

| Type of breast infection | Organism | No allergy to penicillin | Allergy to penicillin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lactational mastitis and breast abscess | Staphylococcus aureus, (Staphylococcus epidermidis) (streptococci) | Flucloxacillin or dicloxacillin | Erythromycin/clarithromycin or cephalexin/clindamycin |

Duration of Antibiotics

The recommended duration of antibiotic therapy is 10 days [4, 22, 23, 24].

Specific Measures: USG-guided Drainage Versus Incision and Drainage

Tewari and Shukla from Banaras Hindu University described a minimally invasive palpatory method of drainage of breast abscess that does not require hospitalization or ultrasonographic facilities. Percutaneous placement of suction drainage catheter in puerperal breast abscess for 3–7 days is effective, devoid of any complication and, scarless, and allows the woman to continue breastfeeding (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Percutaneous aspiration

However, the suction drain insertion is recommended only in large abscesses or which refill rapidly after aspiration [25, 26]. Sharma described that the ultrasound facilities are available in most of areas in India, and the use of ultrasound would minimize the chances of recurrent and residual abscess if its use is promoted in the primary health centers in the remote areas [27].

Ultrasound-guided drainage in combination with oral antibiotics was shown to be an effective treatment for breast abscess, especially for the group with puerperal abscesses. No other factors, including whether treatment was conducted using needle aspiration or catheter drainage, had any independent effect on the recovery. Ultrasound-guided needle aspiration of abscesses with a maximum diameter of less than 3 cm and USG-guided catheter treatment of abscesses with a maximum diameter of 3 cm and larger are safe, well tolerated, and successful means of treating breast abscesses in lactating women [19]. Treatment failure using ultrasound-guided drainage has been reported in cases where either the abscess has been larger than 3 cm in diameter or if it was placed centrally in a subareolar position [28].

It is sad to observe that even in year 2010, some institutions practice incision under general anesthesia combined with drainage tube insertion [22]. The harmful effects of “incision and drainage” include painful wound on the breast (breast is a very richly innervated organ), need of regular dressings, and inability to breastfeed, and possibility of cutting a milk duct leading to “milk fistula” [16]. Ultrasound-guided drainage causes less scarring, does not affect breastfeeding, and does not require general anesthesia or hospitalization [16]. Ultrasound-guided drainage is a less expensive procedure than surgery [15]. Needle puncture of lactating breasts has been associated with fistula formation [16]. Ultrasound-guided drainage reduces the risk of fistula formation in both puerperal and non-puerperal abscesses. It is less invasive than traditional surgery and has a high rate of success.

In treatment of resistant cases, where the abscess is unresponsive to the combination of repeated drainage and oral antibiotics, surgical treatment still has a role. The reason for not responding to aspiration may be presence of thick pus, resistant bacteria, multiloculated abscess cavity where only superficial part has been aspirated, or unusual pathology, viz, tuberculosis, inflammatory carcinoma, or an immune-compromised host. Therefore in such case of not making satisfactory clinical recovery in 1 week, an ultrasound-guided biopsy and blood tests for human immunodeficiency virus are considered. Surgery is also needed in cases with superficial abscesses with skin necrosis. The surgical excision of necrosed skin is necessary for healing. Surgical drainage might result in adhesions in glandular tissue, breast deformity, and unsightly scar formation [22].

Summary

During the cellulitic phase, treatment with antibiotics may be expected to give rapid resolution. The predominance of S. aureus allows a rational choice of antibiotic without having to wait for the results of bacteriological culture. Erythromycin should be considered the drug of choice because it has high efficacy, is low cost, and has low risk of inducing bacterial resistance. Antibiotics should be continued for 10 days to reduce systemic infection and local cellulitis. Where an abscess has formed, aspiration of the pus, preferably under ultrasound control, has now supplanted open surgery as the first line of treatment. Regular natural milk emptying of the breast is an essential part of treatment.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest

None of the authors have any conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Dener C, Inan A. Breast abscesses in lactating women. World J Surg. 2003;27(2):130–133. doi: 10.1007/s00268-002-6563-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bharat A, Gao F, Aft RL. Predictors of primary breast abscesses and Recurrence. World J Surg. 2009;33(12):2582–2586. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0170-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berens PD. Prenatal, intrapartum, and postpartum support of the lactating mother. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2001;48(2):365–375. doi: 10.1016/S0031-3955(08)70030-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kvist LJ, Rydhstroem H. Factors related to breast abscess after delivery: a population-based study. BJOG. 2005;112(8):1070–1074. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rizzo M, Peng L, Frisch A. Breast abscesses in nonlactating women with diabetes: clinical features and outcome. Am J Med Sci. 2009;338(2):123–126. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181a9d0d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benson EA, Goodman MA (1970) Incision with primary suture in the treatment of acute puerperal breast abscess. Br J Surg 57(1):55–58 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Hayes R, Michell M, Nunnerly HB. Acute inflammation of breast—the role of breast ultrasound in diagnosis and management. Clin Radiol. 1991;44(4):253–256. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9260(05)80190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor MD, Way S. Penicillin in treatment of acute puerperal mastitis. Br Med J. 1946;2(4480):731. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.4480.731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Osterman KL, Rahm VA. Lactation mastitis: bacterial cultivation of breast milk, symptoms, treatment, and outcome. J Hum Lact. 2000;16(4):297–302. doi: 10.1177/089033440001600405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roberts KL, Reiter M, Schuster D. A comparison of chilled and room temperature cabbage leaves in treating breast engorgement. J Hum Lact. 1995;11(3):191–194. doi: 10.1177/089033449501100319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smriti A, Manju V, Vatsla DA. Comparison of cabbage leaves vs. hot and cold compresses in the treatment of breast engorgement. Indian J Community Med. 2008;33(3):160–162. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.42053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nikodem VC, Danziger D, Gebka N, Gulmezoglu AM, Hofmeyr GJ. Do cabbage leaves prevent breast engorgement? A randomized, controlled study. Birth. 1993;20(2):61–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.1993.tb00418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomsen AC, Espersen T, Maigaard S. Course and treatment of milk stasis, noninfectious inflammation of the breast, and infectious mastitis in nursing women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1984;149(5):492–495. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(84)90022-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marshall BR, Hepper JK, Zirbell CC. Sporadic puerperal mastitis: an infection that need not interrupt lactation. JAMA. 1975;233:1377–1379. doi: 10.1001/jama.1975.03260130035019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Imperiale A, Zandriono F, Calabrese M, Parodi G, Massa T. Abscesses of the breast: US-guided serial percutaneous aspiration and local antibiotic therapy after unsuccessful systemic antibiotic therapy. Acta Radiol. 2001;42(2):161–165. doi: 10.1080/028418501127346666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barker P. Milk fistula. An unusual complication of breast biopsy. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1988;33(2):106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ulitzsch D, Nyman MK, Carlson RA. Breast abscesses in lactating women: US-guided treatment. Radiology. 2004;232:904–909. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2323030582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roberts KL. A comparison of chilled cabbage leaves and chilled gelpaks in reducing breast engorgement. J Hum Lact. 1995;11(1):17–20. doi: 10.1177/089033449501100118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rolland R, Goeij W. Single dose cabergoline versus bromocriptine in inhibition of puerperal lactation: randomized double blind multicentre study. BMJ. 1991;302:1367–1371. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6789.1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cantlie HB. Treatment of acute puerperal mastitis and breast abscess. Can Fam Physician. 1988;34:2221–2226. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Therapeutic Guidelines: antibiotic. Version 14. Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Ltd; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marchant DJ. Inflammation of the breast. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2002;29(1):89–102. doi: 10.1016/S0889-8545(03)00054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tan SM, Low SC. Non-operative treatment of breast abscesses. Aust N Z J Surg. 1998;68(6):423–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1998.tb04791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferrara JJ, Leveque J, Dyess DL, Lorino CO. Nonsurgical management of breast infections in nonlactating women: a word of caution. Am Surg. 1990;56(11):668–671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwarz RJ, Shrestha R. Needle aspiration of breast abscesses. Am J Surg. 2001;182(2):117–119. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(01)00683-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tewari M, Shukla HS. Effective method of drainage of puerperal breast abscess by percutaneous placement of suction drain. Indian J Surg. 2006;68(6):330–333. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharma R. Drainage of puerperal breast abscess by percutaneous placement of suction drain should not be popularized as a novel surgical technique outside carefully controlled trials. Indian J Surg. 2007;69(1):33. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hook GW, Ikeda DM. Treatment of breast abscesses with US-guided percutaneous needle drainage without indwelling catheter placement. Radiology. 1999;213(2):579–582. doi: 10.1148/radiology.213.2.r99nv25579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]