Abstract

Esophageal perforations are life threatening emergencies associated with high morbidity and mortality. We report on 22 consecutive patients (age 20–86; 13 female and 9 male) with an oesophageal perforation treated at the university hospital Duesseldorf. The patients' charts were reviewed and follow-up was completed for all patients until demission, healed reconstruction or death. Patients' history, clinical presentation, time interval to surgical presentation, and treatment modality were recorded and correlated with patients' outcome. Six esophageal perforations were due to a Boerhaave-syndrome, eleven caused by endoscopic perforation, two after osteosynthesis of the cervical spine and three foreign body induced. In 7 patients a primary local suture was performed, in 4 cases a supplemental muscle flap was interposed, and 7 patients underwent an oesophageal resection. Four patients were treated without surgery (three esophageal stent implantations, one conservative treatment). Eleven patients (50 %) were presented within 24 h of perforation, and 11 patients (50 %) afterwards. Time delay correlates with survival. In 17 (80.9 %) cases a surgical sufficient reconstruction could be achieved. One (4.7 %) patient is waiting for reconstruction after esophagectomy. Four (18.2 %) patients died. A small subset of patients can be treated conservatively by stenting of the Esophagus, if the patient presents early. In the majority of patients a primary repair (muscle flap etc.) can be performed with good prognosis. If the patient presents delayed with extensive necrosis or mediastinitis, oesophagectomy and secondary repair is the only treatment option with high mortality.

Keywords: Esophageal perforations, Boerhaave-syndrome

Introduction

Esophageal perforations are surgical life-threatening emergencies associated with high morbidity and mortality. The therapeutic strategies depend on the cause of the perforation, the time point after perforation, and the comorbidity of the patient [1]. Therapeutic options are diverse and results are often unsatisfactory. Overall mortality still ranges from 20 to 50 % despite advances in surgical and endoscopic techniques as well as intensive care treatment during the past several decades [1–3]. The etiology of esophageal perforation is often iatrogenic, trauma, or Boerhaave syndrome. The classical symptoms of esophageal perforation are pain, fever, cardiac arrhythmia, and the presence of subcutaneous or mediastinal air [3]. Different procedures described for early and delayed esophageal perforation include primary repair with or without reinforcement, simple drainage of the thoracic cavity, diversion esophagectomy, stenting of the perforation with a prosthesis, and esophageal resection with or without primary reconstruction [1, 4, 5]. Radiological imaging and endoscopy are essential in the diagnosis and therapeutic approach to esophageal perforation and mediastinitis. This article reviews etiology, management, and outcome of 22 esophageal perforations. With this experience we tried to create an algorithm in the management of these patients.

Methods

From January 2003 to January 2009, 22 patients were treated for an esophageal perforation at our department.

Patient’s charts, X-rays, and endoscopies were reviewed and follow-up was completed for all patients. Their charts were evaluated regarding medical history, additional diagnosis, etiology of the perforation, time interval to the presentation in our department, patient’s age, and treatment.

In all cases, the localization of perforation was based on endoscopic findings and/or a contrast enhanced X-ray of the esophagus. A CT scan of the chest and upper abdomen was performed in all cases to detect mediastinitis or sign of peritonitis. All patients were admitted to our intensive care unit for further treatment with cardiac and pulmonary monitoring, parenteral feeding, intravenous antibiotics, and proton pump inhibitor. Drainage of the pleura and the mediastinum was performed, if necessary.

Eighteen patients underwent surgical closure of the perforation or esophageal resection. Four patients had a conservative treatment with local drainage or endoscopic stent implantation. Before demission a follow-up contrast swallow was done to exclude a persisting fistula. Complete follow-up information and survival was available for all 22 patients.

Patients with anastomotic leak as a complication after esophagectomy and spontaneous perforation due to esophageal malignancies were excluded.

Results

The twenty-two patients were aged 20–94 years with a median of 55.6 years, 13 female and 9 male patients. Eleven patients were presented within 24 h (early), and 11 patients after 24 h (delayed). Etiology and treatment are summarized in Table 1. The mean hospital stay was 9.3 (7–20) days in the early presented and 68.3 (16–300) days in the delayed presented group.

Table 1.

Etiology, localization, treatment, and outcome of esophageal perforation

| Etiology (n) | localization U/M/L | Esophag-ectomy | Local repair | Muscle flap | Non-op. | Presentation early/delayed | Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iatrogen (11) | |||||||

| Achalasia (3) | 0/0/3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2/1 | 0 |

| Zenker divert. (1) | 1/0/0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1/0 | 0 |

| Healthy eosoph. (7) | 3/3/1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 6/1 | 1 |

| Foreign body (3) induced | 1/0/2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1/2 | 0 |

| Boerhaave (6) syndrome | 0/1/5 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1/5 | 3 |

| Osteosynthesis (2) in cervical spine | 2/0/0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0/2 | 0 |

| Total n (%) 22 | 7/4/11 | 7(27.3) | 7(31.8) | 4(18.2) | 4(18.2) | 11/11 | 4(18.2) |

U/M/L, upper/middle/lower third of the esophagus; early, <24 h; delayed >24 h after perforation

Iatrogenic Perforation

In three patients with achalasia, the pneumatic dilatation resulted in a transmural perforation of the cardia extending into the stomach in one case. Two patients received a local transabdominal repair with fundoplication and primary suture. Both patients were discharged after 12 days. One patient with a delayed presentation received a transmediastinal esophagectomy due to a massive mediastinitis with abscesses and a consecutive esophageal necrosis. The further hospital stay was prolonged by recurrent pneumonias. Mediastinitis with multiple abscess formations needed several CT-guided drainages. One year after perforation, a reconstruction was finally performed with a retrosternal colonic interposition.

In a patient after endoscopic perforation of a Zenker diverticula, a resection and local repair could be performed without any delay. The patient was discharged after 7 days.

In seven patients the esophageal perforation occurred in an otherwise healthy esophagus: gastroscopy (n = 6) and intubation for thyroid surgery (n = 1). In three patients with a cervical perforation, a local closure with an additional muscle flap of the sternocleidomastoid muscle in two cases could be performed. In two cases, with a perforation in the lower third, a transabdominal local repair was performed. One patient underwent a conservative treatment. All patients could be discharged after 7 days. One patient presented delayed with local sepsis and severe necrosis. An esophagectomy was performed. The patient died 5 days later in the ICU ward because of multiorgan failure (MOF).

Foreign Body

Two patients with a foreign body-induced perforation in the middle third were treated by stent implantation. In both patients the stent could be removed after an uneventful course 6 weeks later.

In another patient, who presented late after foreign body perforation, an esophageal resection was performed because of severe local infection with extensive necrosis of the esophagus and sepsis. Three months later after recovery from sepsis, the alimentary tract was reconstructed with a gastric tube and a cervical anastomosis. The initial hospital stay was 28 days, hospital stay after reconstruction 20 days.

Boerhaave Syndrome

Most of our patients with Boerhaave syndrome presented very late in a bad condition with severe mediastinitis and sepsis. Because of the advanced infection with partial necrosis of the esophagus, a transmediastinal esophagectomy was performed in four patients. In one patient the reconstruction was done 4 days later (hospital stay: 24 days). Another patient could not be reconstructed after emergency esophagectomy and was discharged without reconstruction in a nursing home (hospital stay: 16 days). Two patients died because of sepsis and MOF.

One patient received a primary suture with fundoplication. Unfortunately, this patient died 25 days after admission to the intensive care unit of severe sepsis and MOF caused by pneumonia.

One patient presented already with MOF and sepsis. Surgical treatment was not possible. He received an endoscopic stent and chest tubes. Despite maximal intensive care medicine, this patient died 2 days later.

Osteosynthesis of the Cervical Spine

In two cases an osteosynthesis with a ventral plate caused a perforation of the cervical esophagus. One patient showed signs of a local infection. His left neck was explored, necrotic tissue removed, and the defect was closed by primary suture and a latissimus dorsi flap. The patient was discharged after secondary wound healing.

The second patient suffered from giant cell tumor of the cervical spine (C5–7). The patient had multiple resections and local radiotherapy. Ten years later the patient presented with an esophageal stenosis and perforation. The stenosis was resected and reconstructed with a free jejunal interposition. One year later the patient was presented with recurrent perforation of the jejunal interposition. The perforation site was resected, and a new anastomosis was performed and covered by a sternocleidomastoid muscle flap. The osteosynthesis material was removed. The patient was discharged after secondary wound healing.

Discussion

Corresponding to the literature, the etiology of esophagus perforation was mainly iatrogenic in our database [6]. Factors increasing the risk of iatrogenic perforation include preexisting diseases such as large hiatal hernia, vigorous achalasia, or diverticula. Esophageal perforation by instrumentation for ventral plate osteosynthesis [7, 8] typically occurs in areas that are anatomically close to the spine (cervical spine). Therefore, sternocleidomastoid or latissimus dorsi muscle flap interpositions are used as reinforcement of a primary esophageal suture or as a patch in the upper third of the esophagus. If the patient presents early, a primary repair and reconstruction with a muscle flap can be done in most cases with low mortality. In our hospital we had no mortality in those patients. Treatment options include operative and nonoperative managements such as stent implantation [9, 10]. The best indication of stent implantations is small perforations diagnosed early without any signs of sepsis that have an adequate distance to the upper and lower esophageal sphincters for a sufficient sealing [6]. Stent explantation is recommended after 4–6 weeks [6, 11]. A nonoperative treatment in presence of free fluid, contrast extravasation, or mediastinitis on computed tomography is associated with failure and high mortality [12].

Surgical treatment includes manifold different procedures from local repair and muscle flaps up to an esophagectomy depending on the localization, the local infection, and the general condition of the patient. As an individual solution for the reconstruction of a cervical perforation with only very mild circumscribed infection and a neighboring stenosis, we used a jejunal graft. In fact, the free jejunal graft is a very useful technique with wide acceptance for reconstruction after the resection of cervical neck cancers [13].

Because the esophagus is surrounded by loose stromal connective tissue, the infectious and inflammatory response can disseminate easily. Esophageal perforation is a medical emergency. In our series, 11 patients were admitted more than 24 h after perforation. Four of them died because of sepsis and MOF. The objectives of treatment include prevention of further contamination from the perforation, elimination of infection, restoration of the integrity of the gastrointestinal tract, and establishment of nutritional support. Therefore, debridement of infected and necrotic tissue, meticulous closure of the perforation, total elimination of distal obstruction, and drainage of contamination are essential to successful management [14]. Esophagectomy provides the best treatment option, when concomitant obstructive stricture is present, or when attempted drainage, closure, or exclusion has failed to control local infection, necrosis, and sepsis. In these cases, esophagectomy and secondary repair after control of sepsis is the best option to minimize the complication rate [15]. We performed an esophagectomy in seven cases because of massive local infection with secondary esophageal necrosis, mediastinitis, and sepsis. Reconstruction was done in a second stage in five patients (range: 4–300 days after perforation). With this approach, the intra- and postoperative courses after reconstruction were uneventful in three patients.

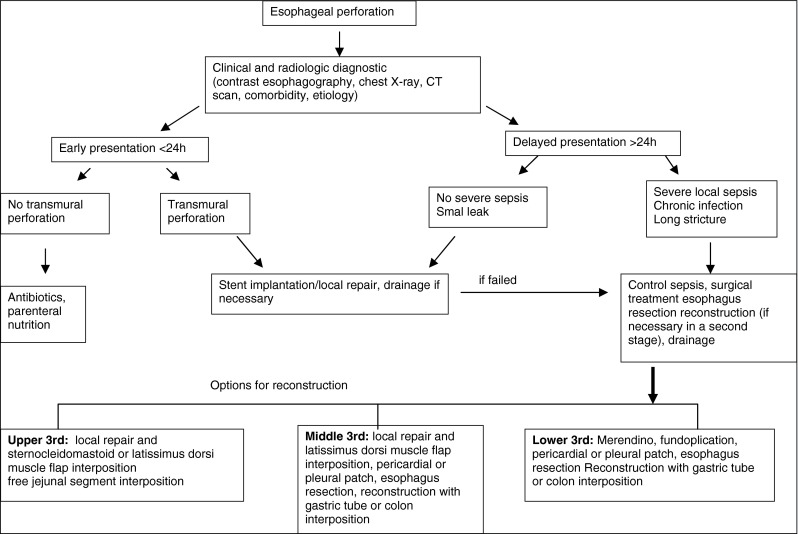

Based on our experience and based on available literature [6, 9, 11, 12, 16], we created a treatment algorithm for our hospital (Fig. 1). Characteristics such as age, ASA classification, and comorbidity should be considered in the treatment of these patients. In conclusion, an early diagnosis and an aggressive treatment are the most important prognostic factors in the therapy of an esophageal perforation. The reason for the high mortality rate is the high percentage of untreated transmural perforations with an advanced mediastinitis and sepsis at the time of diagnosis. A very effective treatment with endoscopic stent implantations or surgical closure with an additional muscle flap, if needed, can lead to success as long as the surrounding infection is only limited.

Fig. 1.

Treatment algorithm for esophageal perforation in our hospital

References

- 1.Udelnow A, Huber-Lang M, Juchems M, Trager K, Henne-Bruns D, Wurl P. How to treat esophageal perforations when determinants and predictors of mortality are considered. World J Surg. 2009;33(4):787–796. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9857-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brinster CJ, Singhal S, Lee L, Marshall MB, Kaiser LR, Kucharczuk JC. Evolving options in the management of esophageal perforation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77(4):1475–1483. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michel L, Grillo HC, Malt RA. Operative and nonoperative management of esophageal perforations. Ann Surg. 1981;194(1):57–63. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198107000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altorjay A, Kiss J, Voros A, Sziranyi E. The role of esophagectomy in the management of esophageal perforations. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;65(5):1433–1436. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(98)00201-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vogel SB, Rout WR, Martin TD, Abbitt PL. Esophageal perforation in adults: aggressive, conservative treatment lowers morbidity and mortality. Ann Surg. 2005;241(6):1016–1021. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000164183.91898.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Heel NC, Haringsma J, Spaander MC, Bruno MJ, Kuipers EJ. Short-term esophageal stenting in the management of benign perforations. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(7):1515–1520. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.von Rahden BH, Stein HJ, Scherer MA. Late hypopharyngo-esophageal perforation after cervical spine surgery: proposal of a therapeutic strategy. Eur Spine J. 2005;14(9):880–886. doi: 10.1007/s00586-005-1006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kau RL, Kim N, Hinni ML, Patel NP. Repair of esophageal perforation due to anterior cervical spine instrumentation. Laryngoscope. 2010;120(4):739–742. doi: 10.1002/lary.20842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chirica M, Champault A, Dray X, et al. Esophageal perforations. J Visc Surg. 2010;147:e117–e128. doi: 10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leers JM, Vivaldi C, Schafer H, et al. Endoscopic therapy for esophageal perforation or anastomotic leak with a self-expandable metallic stent. Surg Endosc. 2009;23(10):2258–2262. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0302-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Babor R, Talbot M, Tyndal A. Treatment of upper gastrointestinal leaks with a removable, covered, self-expanding metallic stent. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2009;19(1):e1–e4. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e318196c706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merchea A, Cullinane DC, Sawyer MD, et al. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy-associated gastrointestinal perforations: a single-center experience. Surgery. 2010;148(4):876–880. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ikeguchi M, Miyake T, Matsunaga T, et al. Free jejunal graft reconstruction after resection of neck cancers: our surgical technique. Surg Today. 2009;39(11):925–928. doi: 10.1007/s00595-008-4050-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidt SC, Strauch S, Rosch T, et al. Management of esophageal perforations. Surg Endosc. 2010;24(11):2809–2813. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Urschel HC, Jr, Razzuk MA, Wood RE, Galbraith N, Pockey M, Paulson DL. Improved management of esophageal perforation: exclusion and diversion in continuity. Ann Surg. 1974;179(5):587–591. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197405000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta NM, Kaman L. Personal management of 57 consecutive patients with esophageal perforation. Am J Surg. 2004;187(1):58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2002.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]