Abstract

Background

To investigate changes over time in risk factors for the development of Activities of Daily Living (ADL) disabilities in older adults with arthritis.

Methods

The data were obtained from the Longitudinal Survey of Health and Living Status of the Elderly in Taiwan (1989–1999). The major analytic cohort comprised 977 older adults (458 men and 519 women) with arthritis and without ADL limitation at study baseline. A generalized estimating equations (GEE) model was used to analyze all temporally correlated errors, population-averaged estimates, and longitudinal relationships.

Results

Overall, the cumulative incidence of ADL disability in the analytic cohort was 17.4% during an observation period of 11 years. With respect to baseline risk, ADL disability was associated with older age, presence of comorbid chronic conditions, and poor self-rated health. However, the findings changed after accounting for the time-varying nature of risk factors and the temporal sequence of possible cause-and-effect relationships. In addition to the baseline predictors, a high score on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, lack of regular exercise, and becoming widowed were associated with an increased risk of ADL disability and a decreased chance of recovery.

Conclusions

An understanding of the time-varying nature of risk factors for the disabling process is essential for the development of effective interventions that aim to maintain functional ability and prevent limitations among older adults with arthritis.

Key words: arthritis, older people, ADL disability, time-varying risk factors, longitudinal study

INTRODUCTION

Arthritis is a chronic condition highly prevalent among older populations.1–4 Aside from its high prevalence, arthritis has a large effect on the health status of elderly populations and, among all chronic conditions, it is the leading cause of long-term disability from both an individual and population perspective.3–7 The necessity of understanding the role and risk of arthritis in developing chronic activities of daily living (ADL) disability is becoming an urgent public health issue.

The development of disability in older adults is complex, as it involves multiple and possibly interrelated disability episodes. It has been noted that disability in older populations is a recurrent rather than an enduring condition, which suggests that intervention to maintain independence after recovery is needed.8–11 The literature on functional limitation in arthritis includes a wealth of cross-sectional studies but few longitudinal studies, and no longitudinal study has investigated an Asian population.12–15

Furthermore, the timing of risk factors may be more important than their mere occurrence during arthritis progression. Unfortunately, previous studies have not specifically examined the time-varying nature of risk factors for the longitudinal development of ADL disability in older adults with arthritis.

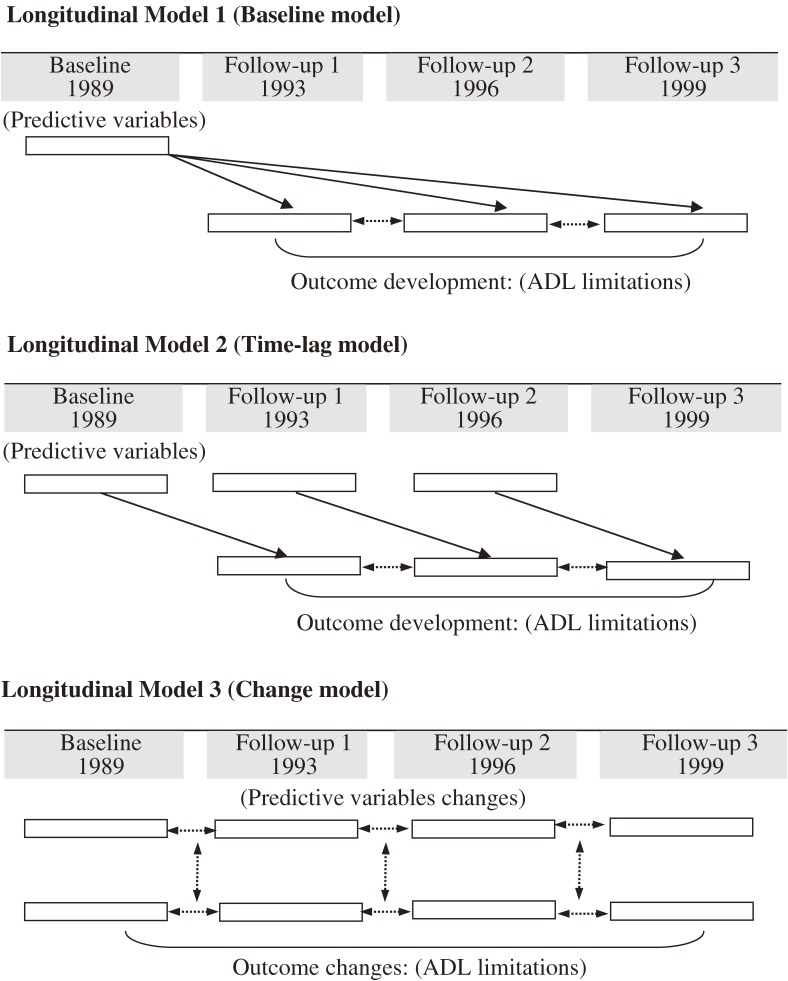

The present study used 3 longitudinal analyses,16–19 including repeated measurements of demographic, lifestyle, and psychological variables and other background data, to assess dynamic risk factors and longitudinal development of ADL disability in older adults with arthritis (Figure 1). The analysis used longitudinal data for a recent 11-year period from the Longitudinal Survey of Health and Living Status of the Elderly in Taiwan.

Figure 1. Illustration of 3 longitudinal models used for analysis of risk factors for functional decline in older adults with arthritis. Model 1: Baseline measurements of risk factors were assumed to be related to functional decline reported at 3 follow-up points. Model 2: All risk factors were modeled using data collected at the examination preceding the assessment of the outcome variable (ADL disability). In this model, longitudinal causal relationships between ADL disability and risk factors were analyzed by using all available data, not only with respect to correlation in time sequence, but also with regard to correlation between time-dependent and time-independent variables. Model 3: Changes between 2 consecutive measurements of outcome and predictor variables were studied. We investigated relations between changes in values between different time points, rather than the actual values.

METHODS

Study population

The Longitudinal Survey of Health and Living Status of the Elderly in Taiwan was launched in 1989. It was a cooperative undertaking between the Taiwan Provincial Institute of Family Planning and the Population Studies Center and Institute of Gerontology at the University of Michigan.20 An important strength of this survey is that it represents the entire elderly population of Taiwan. The design of the original study is described briefly here and in detail elsewhere.20–23

Overall, a total of 4049 subjects completed interviews for the baseline study (1989), which corresponded to a response rate of 91.8%. Proxy interviews were needed for only 189 cases, representing 4.4% of all completed interviews and 4.1% of the total sample. Proxies provided information only on matters that could be observed. Their reports appeared to be reliable.20–23 Three follow-up interviews (in 1993, 1996, and 1999) were the longitudinal components of the survey. The number of cumulative deaths was 582 in 1993, 1047 in 1996, and 1486 in 1999. Response rates for the 3 follow-up surveys were 91.0%, 88.9%, and 90.1%, respectively.

Arthritis classification

A subject was classified as having arthritis if they answered affirmatively to the question, “Have you ever had, or has a doctor ever told you that you have, arthritis or rheumatism?” Self-reported history of arthritis is relevant from a public policy perspective because many persons with arthritis do not consult a health care provider for treatment.24 In addition, subjects with arthritis were asked another question, “How much inconvenience has arthritis caused in your daily living?” The response options included, on an ordinal scale: “no inconvenience at all,” “some inconvenience,” and “a lot of inconvenience.” The latter 2 responses were defined as “self-perceived inconvenience caused by arthritis.”

Disability outcomes

All 4 interviews included identical sets of questions regarding self-reported information on disability status. The modified Katz ADL Scale25 was used to assess self-reported ability to perform 6 basic activities without help: bathing, dressing, walking across a room, transferring from a bed to a chair, eating, and toileting. For each set of questions, a score corresponding to the number of items with disability was calculated. Thus, higher scores indicated greater limitation in physical function, and a score of 0 indicated no difficulty in all items. If there was a missing response to any item, that set of questions was treated as missing.

Assessment of other covariates

Other variables included in the analysis were structured questions about sociodemographic characteristics, health, psychological variables, and lifestyle. Sociodemographic characteristics included age (in years), sex, education (years of schooling completed), and marital status (married, widowed, and other). Health and psychological variables included body mass index (BMI), and a summary measure of chronic health conditions was calculated using a diagnosis checklist. Self-rated health was assessed using a single item, “Regarding your state of health, do you feel it is excellent [coded 1], good, average, not so good, or very poor [coded 5].” Thus, higher scores indicated a perception of poorer health. In identifying trajectory stability, 5-category self-rated health was then simplified into “good” (excellent, good, or average) and “poor” (not so good or very poor). The presence of depressive symptoms was then evaluated by using an abbreviated 10-item version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies–Depression Scale (CES-D).26 Lifestyle measures assessed included personal habits such as betel chewing, alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking, and routine exercise. These habits were evaluated by using the questions, “Do you [description of habit]?” and “Did you ever [description of habit]?”

Statistical analysis

The progression of study variables was described at baseline and during follow-up, and is summarized as the mean and standard deviation for continuous variables and as proportions for categorical variables. The generalized estimating equation (GEE) method was used to analyze repeated measurements.16 The GEE method extends standard regression analysis and accounts for the correlation between repeated measurements. Three longitudinal models were used in this study (Figure 1). In longitudinal model 1 (baseline model), all risk factors were measured at baseline. These baseline measurements were hypothesized to be related to ADL disability reported at the 3 follow-up points. In longitudinal model 2 (time-lag model), all risk factors were modeled using data from the examination that preceded measurement of the outcome variable (ADL disability). In this model, longitudinal causal relationships between ADL disability and risk factors were analyzed by using all available data. Correlation in time sequence was investigated, as was correlation between time-dependent and time-independent variables. Therefore, the time-lag model yielded a better understanding than model 1 of the specific time-varying nature of exposures. In addition, the time-lag model accounts for the temporal sequence in a possible cause-and-effect relationship. Finally, in order to assess changes occurring between 2 consecutive measurements of both the outcome and predictor variables, longitudinal model 3 (change model) analyzed associations between changes in values, rather than those between the actual values. In model 1 and model 2, scores for ADL disability were dichotomized according to whether there was a disability in 1 or more items (score = 1) or not (score = 0). Then, the model with a dichotomous outcome variable was analyzed using (longitudinal) logistic regression, and odds ratios (ORs) were calculated. However, model 3 was introduced to analyze changes in ADL numbers between different time-points. In all analyses, a P value <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. All longitudinal analyses were performed with the statistical package SAS version 9.13 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Table 1 shows information on respondents and response rates for each study year. As the table shows, the cumulative number of deaths was 582 in 1993, 1047 in 1996, and 1486 in 1999. Response rates for the 4 surveys were 91.8%, 91.0%, 88.9%, and 90.1%, respectively. One particularly attractive feature was the extraordinarily high response rate that was achieved from the baseline study to follow-ups, so the loss to follow-up bias would be not to an important degree.20–23 Because the current study was principally interested in risk factors for the development of disability in older adults with arthritis, the eligible study population was initially defined as adults older than 60 years at baseline who were free of any form of ADL disability. A total of 3353 subjects were thus included in the study cohort. Then, the study cohort was then divided into 2 analytic cohorts composed of 2376 subjects (1151 men and 865 women) without arthritis at baseline and 977 subjects (458 men and 519 women) with arthritis at baseline (the major analytic cohort for this study; Table 2).

Table 1. Number of respondents and response rate for each study year of the Longitudinal Survey of Health and Living Status of the Elderly in Taiwan.

| Calendar year | ||||

| 1989 | 1993 | 1996 | 1999 | |

| Probability sample (n) | 4412 | |||

| Completed cohort (n) | 4049 | 3155 | 2669 | 2310 |

| Death (n) | — | 582 | 1047 | 1486 |

| Loss to follow-up (n) | 363 | 312 | 333 | 253 |

| Respondent rate (%) | 91.8 | 91.0 | 88.9 | 90.1 |

Table 2. Physical function, demographic, psychological, and lifestyle variables, and chronic health conditions of subjects at baseline (1989) and follow-up (1993–1999) examinations.

| Calendar year | ||||

| 1989 | 1993 | 1996 | 1999 | |

| Study cohorta (n) | 3353 | 2712 | 2321 | 2017 |

| Sex (Male/Female) | 1969/1384 | 1569/1143 | 1333/988 | 1136/881 |

| Age, yrs (mean ± SD) | 67.56 ± 6.12 | |||

| Analytic cohort 1b (n) | 2376 | |||

| Sex (Male/Female) | 1511/865 | |||

| Age, yrs (mean ± SD) | 67.52 ± 6.17 | |||

| Education, yrs (mean ± SD) | 4.25 ± 4.70 | |||

| ADL limitation | ||||

| Moderate (1–2 ADL limitations) | — | 1.5% | 2.3% | 2.9% |

| Severe (3+ ADL limitations) | — | 3.8% | 5.3% | 8.8% |

| Analytic cohort 2c (n) | 977 | 778 | 666 | 588 |

| Sex (Male/Female) | 458/519 | 359/419 | 306/360 | 258/330 |

| Age, yrs (mean ± SD in yrs) | 67.68 ± 6.01 | |||

| Education, yrs (mean ± SD in yrs) | 3.86 ± 4.56 | |||

| ADL limitation | ||||

| Moderate (1–2 ADL limitations) | — | 3.1% | 2.9% | 3.1% |

| Severe (3+ ADL limitations) | — | 5.8% | 9.5% | 14.3% |

| No. of chronic health conditions (mean ± SD) | 2.24 ± 1.73 | 2.25 ± 1.65 | 2.32 ± 1.76 | 2.76 ± 1.90 |

| CES-D score (mean ± SD) | 7.50 ± 5.49 | 7.56 ± 6.27 | 7.55 ± 6.16 | 7.52 ± 6.87 |

| Self-perceived health (mean ± SD) | 5.46 ± 1.30 | 5.37 ± 1.41 | 4.78 ± 1.26 | 5.91 ± 1.37 |

| Routine physical exercise | 20.3% | 34.1% | 35.4% | 34.0% |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.60 ± 3.83 | 23.35 ± 3.40 | 22.82 ± 3.44 | 22.75 ± 3.42 |

| Smoking (current) | 29.8% | 23.9% | 23.2% | 20.1% |

| Alcohol consumption (current) | 18.7% | 16.5% | 16.4% | 20.5% |

| Betel chewing (current) | 5.1% | 4.9% | 3.8% | 4.1% |

| Being widowed | 35.7% | 38.7% | 46.1% | 58.1% |

aSubjects without ADL limitation at baseline.

bSubjects without arthritis or ADL limitation at baseline.

cSubjects with arthritis and without ADL limitation at baseline.

Abbreviations: SD, Standard Deviation; ADL, Activities of Daily Living; CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Studies–Depression Scale.

Table 2 shows information on the subjects’ physical function, demographic, psychological, and lifestyle characteristics, and chronic health conditions at baseline, in 1989, and at follow-up in 1993, 1996, and 1999. Overall, the cumulative incidence of ADL disability during the 11-year follow-up period was 2.9% in analytic cohort 1 and 3.1% in analytic cohort 2, among those with moderate disability (1–2 ADL limitations), and 8.8% and 14.3%, respectively, among those with severe disability (3+ ADL limitations).

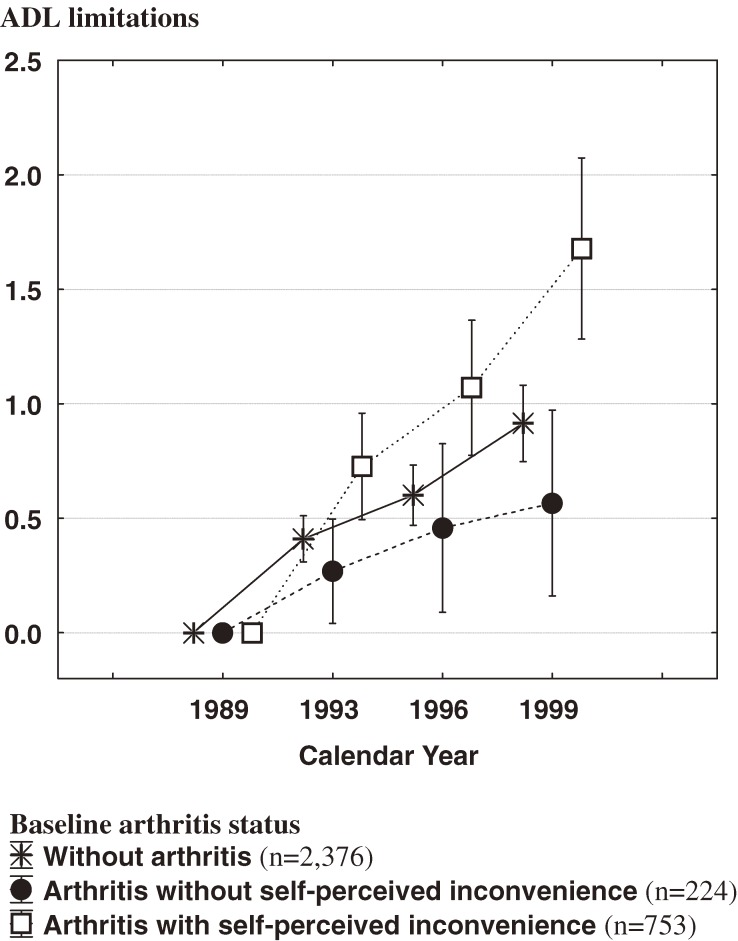

At baseline, the proportion of subjects with self-perceived inconvenience was 77.1% (753/977) among those with arthritis. Figure 2 displays longitudinal changes in mean ADL and its 95% confidence interval from baseline to 1999. There was an increasing trend in ADL limitations for all 3 groups from the study cohort. In addition, the results indicate that the average rate of increase during the follow-up period was highest among subjects with arthritis who reported inconvenience due to the condition. By contrast, the lowest average rate was found among subjects with arthritis and no self-perceived inconvenience.

Figure 2. Changes in mean activities of daily living (ADL) score during the 11-year follow-up period, by baseline arthritis status (higher scores indicate a greater number of ADL limitations; a score of 0 indicates no difficulty on any item).

To determine the strongest predictors of development of ADL disability in older adults with arthritis, the relative effects were estimated by using adjusted ORs and regression coefficients, after controlling for demographic differences, chronic health conditions, health behaviors, psychological factors, and other study variables (Table 3).

Table 3. Odds ratiosa (ORs, model 1 and model 2), regression coefficientsa (model 3), and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) in univariate and multivariate analysis of risk factors for ADL disability in older adults with arthritis, at baseline (1989) and follow-up (1993, 1996, and 1999).

| Parameters | Longitudinal model 1 (Baseline model) |

Longitudinal model 2 (Time-lag model) |

Longitudinal model 3 (Changes model) |

|||||||||

| Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

|||||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI | |

| Age, yrs | 1.10 | 1.07 to 1.12 | 1.09 | 1.07 to 1.13 | 1.13 | 1.10 to 1.15 | 1.09 | 1.05 to 1.12 | 0.09 | 0.07 to 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.07 to 0.12 |

| Sex (male vs female) | 0.72 | 0.52 to 0.98 | NS | NS | 0.72 | 0.52 to 0.98 | NS | NS | −0.14 | −0.38 to 0.13 | NS | NS |

| Self-perceived inconvenience caused by arthritis (yes vs no) |

2.46 | 1.58 to 3.82 | NS | NS | 2.65 | 1.63 to 4.31 | NS | NS | 0.75 | 0.38 to 1.13 | 0.59 | 0.28 to 0.97 |

| No. of chronic health conditions | 1.21 | 1.10 to 1.32 | 1.13 | 1.02 to 1.25 | 1.26 | 1.18 to 1.35 | 1.15 | 1.04 to 1.26 | 0.11 | 0.08 to 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.04 to 0.28 |

| Self-rated healthb | 1.29 | 1.13 to 1.45 | 1.21 | 1.05 to 1.39 | 2.10 | 1.82 to 2.43 | 1.57 | 1.27 to 1.94 | 0.22 | 0.15 to 0.27 | 0.15 | 0.09 to 0.31 |

| Routine exercise (yes vs no) | 0.85 | 0.57 to 1.27 | NS | NS | 0.23 | 0.17 to 0.32 | 0.40 | 0.26 to 0.62 | −1.33 | −1.07 to −1.47 | −1.24 | −1.05 to −1.41 |

| CES-D scorec | 1.05 | 1.02 to 1.08 | NS | NS | 1.06 | 1.05 to 1.07 | 1.07 | 1.04 to 1.10 | 0.06 | 0.04 to 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.05 to 0.07 |

| Being widowed (yes vs no) | 1.88 | 1.38 to 2.63 | NS | NS | 2.43 | 1.81 to 3.22 | 1.42 | 1.13 to 2.01 | 0.45 | 0.21 to 0.68 | 0.36 | 0.29 to 0.83 |

aThe working correlation matrix is autoregressive.

bHigher scores indicate poorer self-rated health status; cHigher scores indicate a greater number of depressive symptoms.

Other study covariates that were not significant in multivariate analysis were included, namely, education level, body mass index, smoking, alcohol consumption, and betel chewing.

NS: not significant.

Abbreviations: ADL, activities of daily living; CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Studies–Depression Scale.

In model 1 (baseline model), significant risk factors for longitudinal development of ADL disability at baseline were age (adjusted OR, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.07–1.13), number of chronic health conditions (1.13, 1.02–1.25), and poor self-rated health (1.21, 1.05–1.39).

In model 2 (time-lag model), all risk factors were modeled using data from the examination that preceded measurement of the outcome variable (ADL disability). Thus, in the analysis of change during the 11-year follow-up period, the temporal sequence of possible cause-and-effect relationships between risk factors and ADL disability could be evaluated. Development of ADL disability was significantly associated with age (adjusted OR, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.05–1.12), number of chronic health conditions (1.15, 1.04–1.26), poor self-rated health (1.57, 1.27–1.94), CES-D score (1.07, 1.04–1.10), with regular exercise (0.40, 0.26–0.62), and being widowed (1.42, 1.13–2.01).

In model 3 (change model), changes between 2 consecutive measurements of ADL disability were significantly associated with age (adjusted β = 0.08; 95% CI, 0.07–0.12), self-perceived inconvenience caused by arthritis (0.59, 0.28–0.97), number of chronic health conditions (0.08, 0.04–0.18), poor self-rated health (1.57, 1.27–1.94), CES-D score (0.06, 0.05–0.07), regular exercise (−1.24, −1.05 to −1.41), and being widowed (0.36, 0.29–0.83). Finally, in all models, there was no particular “period” effect (eg, in the baseline risk model, calendar year 1999 vs 1993: OR = 0.73, 95% CI 0.51–1.15; calendar year 1996 vs 1993: OR = 0.83, 95% CI 0.62–1.10).

DISCUSSION

Given the worldwide increase in the numbers of older adults with arthritis, understanding the role of arthritis in the development of ADL disability is becoming an urgent public health issue. Risk factors for the onset of ADL limitations in older adults with arthritis have been discussed previously.3,15,27–29 Our study presents evidence of the time-varying nature of these risk factors on the development of ADL disability in older adults with arthritis. The advantages of our analysis as compared with traditional techniques are: 1) all longitudinal data are used to estimate one regression coefficient indicating the overall relationship, 2) all relationships can be estimated after correction for both time-dependent and time-independent covariates, and 3) when a GEE model is used to calculate the parameters of these 2 models, it is possible that different subjects have a different number of repeated measurements. Hence, with respect to baseline risk, the results indicate that older age, presence of comorbid chronic conditions, and poor self-rated health were associated with ADL disability over a period of 11 years in older adults. However, the findings changed after taking into account the time-varying nature of risk factors and possible cause-and-effect relationships. In addition to the baseline risk factors, higher CES-D score, lack of regular exercise, and being widowed were also significantly associated with an increased risk of becoming ADL-disabled during follow-up.

It has been reported that the onset of ADL disability is a complex process, and that medical, demographic, psychological, and behavioral triggers are all important.30,31 Our observation that older age, presence of comorbid chronic conditions, and poor self-rated health are associated subsequent ADL deterioration is in agreement with previous research.3,15,28,31–38 Moreover, our data indicate that these 3 factors and their timing have different epidemiologic roles in the risk of arthritis. As noted above, we found that older age, presence of comorbid chronic conditions, and poor self-rated health were the only predictors of ADL disability at baseline. However, the time-varying nature of these 3 factors was also important in the longitudinal development of ADL disability among older adults with arthritis. It may be that older age, comorbid chronic conditions, and poor self-rated health are the initial biological conditions that increase the subsequent risk of ADL disability, and that the risks posed by these factors are proportional to the length of exposure to, or increase in, these 3 factors. Our focus on the experience of an arthritis cohort makes these findings relevant to the design of public health interventions and prevention programs that aim to maintain and improve function among older adults with this condition.

In addition to older age, presence of comorbid chronic conditions, and poor self-rated health, our analysis of longitudinal time-varying relationships indicates that CES-D score, lack of regular exercise, and being widowed could predict the development of ADL disability during follow-up, which suggests the importance of the temporal sequence and time-varying nature of risk factors in the relationships between arthritis and subsequent ADL disability. This was consistent with evidence indicating that regular exercise reduces the incidence of ADL disability in older adults with knee osteoarthritis.15,34,35 Exercise may be an effective strategy for preventing ADL disability and, consequently, may extend the period of autonomy in older adults. Regarding depressive symptoms, the potential advantages of including a psychoeducational intervention in treatment options for arthritis are becoming increasingly recognized.33 Studies have also shown that arthritis patient education programs can be useful for enhancing self-care management techniques and improving physical and psychological health outcomes.37,38 Furthermore, it has been reported that becoming widowed and the duration of widowhood are important determinants for the onset of late-life disability in different disability domains.39,40 Previous study results have also highlighted the importance of focusing not only on the short-term effects of socioeconomic factors, but also on the possibility of long-term effects on disability in older adults.41 From an epidemiologic perspective, our results indicate that lack of regular exercise, depressive symptoms, and becoming widowed are associated with an increased likelihood of ADL disability and a decreased chance of recovery in older populations with arthritis. Moreover, the combination of baseline and time-varying risk factors may increase the future risk of ADL disability.

It is interesting to note that subjects with arthritis who had no self-perceived inconvenience had a lower incidence of ADL disability than did subjects without arthritis. In fact, in our crude analysis, self-perceived inconvenience caused by arthritis was a significant factor in all longitudinal models, particularly with respect to between-examination changes in ADL limitations. However, the relationship became insignificant in the other 2 longitudinal models, after adjustment for age, comorbid chronic conditions, poor self-rated health, marital status, and CES-D score. Interestingly, changes in ADL numbers between different time-points were related. The change model allows separation between the within-person relationship (longitudinal) and the between-person relationships (cross-sectional). In view of the fact that the other 2 models showed no independent relation, it is possible that, in subjects with self-perceived inconvenience who developed ADL disability, longitudinal within-person relationships will be overruled by the between-person relations when the variation in actual values between subjects exceeds the change over time within subjects. In addition, the results also suggest the presence of interrelationships between self-perceived inconvenience caused by arthritis and other risk factors for ADL disability. Also, the disabilities of adults with arthritis tend to accumulate gradually rather than occurring simultaneously.42 It has been reported that, during the course of arthritis, patients can learn to adjust to their condition and its consequences, and are thus able to maintain a normal stress level.43 Other studies have noted substantial intraindividual variation, which may be due to differences in disease-related factors such as joint tenderness, pain, and disability.9–11,44 A previous study reported that a significant relationship exists between arthritis onset and worsening pain, resulting in the development of activity limitation.32 However, our analysis did not control for chronic pain conditions due to the lack of such information in the present cohort data. Chronic pain is probably associated not with only arthritis, but also self-rated health, motivation for and compliance with regular exercise, and depressive mood. Therefore, a better understanding of how chronic pain affects the interrelationships between self-perceived inconvenience caused by arthritis and other risk factors in the development of disability is essential if effective prevention and intervention programs are to be developed. That is, we need to recognize how different trajectories in self-perceived inconvenience caused by arthritis are related to the disabling process in adults with different demographic, biological, and psychological characteristics.

This report suffers from a number of limitations, which we will briefly discuss. First, although arthritis is one of the most important causes of disability in elderly individuals, especially impairment of the joints of the lower extremities, rheumatoid arthritis (RA) could not be distinguished from osteoarthritis (OA) in our analysis. Inconvenience and ADL disability depend on whether an impairment originates in the lower or upper extremities. Therefore, arthritis may lead to severe and even total disability in an individual, especially when it is associated with other comorbidities (eg, dementia).45,46 However, from a population perspective, the combining of RA and OA is not of great importance. Nevertheless, additional studies are needed to further examine the time-varying nature of risk factors in the disabling process of older adults with rheumatoid arthritis. A second limitation of this study is that the findings do not consider the influence of additional factors (eg, specific cognitive impairments or environmental factors) known to influence the development of disability. Despite the absence of these factors in our analysis, the current exploratory analyses do provide sufficient evidence to discuss the importance of the time-varying nature of risk factors in the longitudinal development of disability in an older population. Future studies will likely examine a more comprehensive set of risk factors and their associations with different functional outcomes. Finally, our study results are limited to an older Chinese population, so studies in other ethnic populations are necessary.

In conclusion, this research has revealed longitudinal relations between risk factors and the development of ADL disability in older adults with arthritis. Older age, presence of comorbid chronic conditions, and poor self-rated health were the most important risk factors at baseline and need to be carefully monitored. In addition, lack of regular exercise, depressive symptoms, and becoming widowed may increase the risk of ADL disability and decrease the chance of recovery in older adults with arthritis. An understanding of the time-varying nature of risk factors in the disabling process is essential to develop effective interventions to help maintain functional ability and prevent limitations among older adults with arthritis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study used data from the Longitudinal Survey of Health and Living Status of the Elderly in Taiwan, provided by the Bureau of Health Promotion, Department of Health, ROC (Taiwan). The conclusions expressed herein do not represent those of the Bureau.

REFERENCES

- 1.al Snih S , Markides KS , Ray L , Freeman JL , Goodwin JS. Prevalence of arthritis in older Mexican Americans . Arthritis Care Res. 2000;13:409–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hughes SL , Dunlop D. The prevalence and impact of arthritis in older persons . Arthritis Care Res. 1995;8:257–64 10.1002/art.1790080409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Song J , Chang HJ , Tirodkar M , Chang RW , Manheim LM , Dunlop DD. Racial/ethnic differences in activities of daily living disability in older adults with arthritis: a longitudinal study . Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:1058–66 10.1002/art.22906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kondo K , Tanaka T , Hirota Y , Kawamura H , Miura H , Sugioka Y , et al. Factors associated with functional limitation in stair climbing in female Japanese patients with knee osteoarthritis . J Epidemiol. 2006;16:21–9 10.2188/jea.16.21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al Snih S , Markides KS , Ostir GV , Goodwin JS. Impact of arthritis on disability among older Mexican Americans . Ethn Dis. 2001;11:19–23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verbrugge LM , Gates DM , Ike RW. Risk factors for disability among US adults with arthritis . J Clin Epidemiol. 1991;44:167–82 10.1016/0895-4356(91)90264-A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunlop DD , Manheim LM , Song J , Chang RW. Arthritis prevalence and activity limitations in older adults . Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:212–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beckett LA , Brock DB , Lemke JH , Mendes de Leon CF , Guralnik JM , Fillenbaum GG , et al. Analysis of change in self-reported physical function among older persons in four population studies . Am J Epidemiol. 1996;143:766–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hardy SE , Gill TM. Recovery from disability among community-dwelling older persons . JAMA. 2004;291:1596–602 10.1001/jama.291.13.1596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang J , Tang Z , Meng XJ , Futatsuka M. Demographic determinants for change in activities of daily living: a cohort study of the elderly people in Beijing . J Epidemiol. 2002;12:280–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hardy SE , Gill TM. Factors associated with recovery of independence among newly disabled older persons . Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:106–12 10.1001/archinte.165.1.106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rejeski WJ , Miller ME , Foy C , Messier S , Rapp S. Self-efficacy and the progression of functional limitations and self-reported disability in older adults with knee pain . J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2001;56:S261–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ng TP , Niti M , Chiam PC , Kua EH. Prevalence and correlates of functional disability in multiethnic elderly Singaporeans . J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:21–9 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00533.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kishimoto M , Ojima T , Nakamura Y , Yanagawa H , Fujita Y , Kasagi F , et al. Relationship between the level of activities of daily living and chronic medical conditions among the elderly . J Epidemiol. 1998;8:272–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunlop DD , Semanik P , Song J , Manheim LM , Shih V , Chang RW. Risk factors for functional decline in older adults with arthritis . Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1274–82 10.1002/art.20968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zeger SL , Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes . Biometrics. 1986;42:121–30 10.2307/2531248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Twisk JW Longitudinal data analysis. A comparison between generalized estimating equations and random coefficient analysis . Eur J Epidemiol. 2004;19:769–76 10.1023/B:EJEP.0000036572.00663.f2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoogendoorn WE , Bongers PM , de Vet HC , Twisk JW , van Mechelen W , Bouter LM. Comparison of two different approaches for the analysis of data from a prospective cohort study: an application to work related risk factors for low back pain . Occup Environ Med. 2002;59:459–65 10.1136/oem.59.7.459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Twisk JW Different statistical models to analyze epidemiological observational longitudinal data: an example from the Amsterdam Growth and Health Study . Int J Sports Med. 1997;18Suppl 3:S216–24 10.1055/s-2007-972718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.1989 Survey of Health and Living Status of the Elderly in Taiwan: Questionnaire and Survey Design. Comparative study of the Elderly in four Asian countries, Research Report No. 1. Issued by Taiwan Provincial Institute of Family Planning, the Population Studies Center and the institute of Gerontology at the University of Michigan, December 1989.

- 21.Wang HP Gender differences in hazard rate affecting death in the elderly population in Taiwan . Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2006;22:277–85 10.1016/S1607-551X(09)70312-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen HJ , Wang HP. Preliminary study of elderly health status in Taiwan: 1989–1999 . Taiwan J Fam Med. 2005;15:25–35(in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang HP Disease, functional status, and self-rated health in Taiwan elderly: 1989–1996 . Taiwanese J Soc Welfare. 2003;3:77–106(in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Adults who have never seen a health-care provider for chronic joint symptoms: United States, 2001 . MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:416–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katz IR , Streim J , Parmelee P. Prevention of depression, recurrences, and complications in late life . Prev Med. 1994;23:743–50 10.1006/pmed.1994.1128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kohout FJ , Berkman LF , Evans DA , Cornoni-Huntley J. Two shorter forms of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression) depression symptoms index . J Aging Health. 1993;5:179–93 10.1177/089826439300500202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song J , Chang RW , Dunlop DD. Population impact of arthritis on disability in older adults . Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55:248–55 10.1002/art.21842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fisher MN , Snih SA , Ostir GV , Goodwin JS. Positive affect and disability among older Mexican Americans with arthritis . Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51:34–9 10.1002/art.20079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strating MM , Van Schuur WH , Suurmeijer TP. Predictors of functional disability in rheumatoid arthritis: results from a 13-year prospective study . Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29:805–15 10.1080/09638280600929151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reynolds SL , Silverstein M. Observing the onset of disability in older adults . Soc Sci Med. 2003;57:1875–89 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00053-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shih VC , Song J , Chang RW , Dunlop DD. Racial differences in activities of daily living limitation onset in older adults with arthritis: a national cohort study . Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:1521–6 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perruccio AV , Power JD , Badley EM. Arthritis onset and worsening self-rated health: a longitudinal evaluation of the role of pain and activity limitations . Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53:571–7 10.1002/art.21317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barlow JH , Turner AP , Wright CC. Long-term outcomes of an arthritis self-management programme . Br J Rheumatol. 1998;37:1315–9 10.1093/rheumatology/37.12.1315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Penninx BW , Messier SP , Rejeski WJ , Williamson JD , DiBari M , Cavazzini C , et al. Physical exercise and the prevention of disability in activities of daily living in older persons with osteoarthritis . Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:2309–16 10.1001/archinte.161.19.2309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fujita K , Nagatomi R , Hozawa A , Ohkubo T , Sato K , Anzai Y , et al. Effects of exercise training on physical activity in older people: a randomized controlled trial . J Epidemiol. 2003;13:120–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kadam UT , Croft PR. Clinical comorbidity in osteoarthritis: associations with physical function in older patients in family practice . J Rheumatol. 2007;34:1899–904 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lorig KR , Mazonson PD , Holman HR. Evidence suggesting that health education for self-management in patients with chronic arthritis has sustained health benefits while reducing health care costs . Arthritis Rheum. 1993;36:439–46 10.1002/art.1780360403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simeoni E , Bauman A , Stenmark J , O'Brien J. Evaluation of a community arthritis program in Australia: dissemination of a developed program . Arthritis Care Res. 1995;8:102–7 10.1002/art.1790080208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van den Brink CL , Tijhuis M , van den Bos GA , Giampaoli S , Kivinen P , Nissinen A , et al. Effect of widowhood on disability onset in elderly men from three European countries . J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:353–8 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52105.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Picavet HS , Hoeymans N. Physical disability in The Netherlands: prevalence, risk groups and time trends . Public Health. 2002;116:231–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Akin B , Ege E , Koçoğlu D , Arslan SY , Bilgili N. Reproductive history, socioeconomic status and disability in the women aged 65 years or older in Turkey . Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010;50:11–5 10.1016/j.archger.2009.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Verbrugge LM , Juarez L. Profile of arthritis disability . Public Health Rep. 2001;116Suppl 1:157–79 10.1093/phr/116.S1.157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Strating MM , Suurmeijer TP , van Schuur WH. Disability, social support, and distress in rheumatoid arthritis: results from a thirteen-year prospective study . Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55:736–44 10.1002/art.22231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smedstad LM , Vaglum P , Moum T , Kvien TK. The relationship between psychological distress and traditional clinical variables: a 2 year prospective study of 216 patients with early rheumatoid arthritis . Br J Rheumatol. 1997;36:1304–11 10.1093/rheumatology/36.12.1304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sokka T , Krishnan E , Häkkinen A , Hannonen P. Functional disability in rheumatoid arthritis patients compared with a community population in Finland . Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:59–63 10.1002/art.10731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hakala M , Nieminen P. Functional status assessment of physical impairment in a community based population with rheumatoid arthritis: severe incapacitated patients are rare . J Rheumatol. 1996;23:617–23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]