Background: Nrf2 has a dual role in tumorigenesis.

Results: Nrf2 activation in colonic epithelial cells is controlled by the stress response gene IER3. Loss of IER3 expression causes enhanced Nrf2 activity, thereby conferring ROS protection and apoptosis resistance.

Conclusion: By regulating Nrf2-dependent cytoprotection, IER3 exerts tumor suppressive activity.

Significance: Loss of control by IER3 favors the protumorigenic action of Nrf2.

Keywords: Colitis, Colon Cancer, Nrf2, Oxidative Stress, Transcription Factors

Abstract

Although nuclear factor E2-related factor-2 (Nrf2) protects from carcinogen-induced tumorigenesis, underlying the rationale for using Nrf2 inducers in chemoprevention, this antioxidative transcription factor may also act as a proto-oncogene. Thus, an enhanced Nrf2 activity promotes formation and chemoresistance of colon cancer. One mechanism causing persistent Nrf2 activation is the adaptation of epithelial cells to oxidative stress during chronic inflammation, e.g. colonocytes in inflammatory bowel diseases, and the multifunctional stress response gene immediate early response-3 (IER3) has a crucial role under these conditions. We now demonstrate that colonic tissue from Ier3−/− mice subject of dextran sodium sulfate colitis exhibit greater Nrf2 activity than Ier3+/+ mice, manifesting as increased nuclear Nrf2 protein level and Nrf2 target gene expression. Likewise, human NCM460 colonocytes subjected to shRNA-mediated IER3 knockdown exhibit greater Nrf2 activity compared with control cells, whereas IER3 overexpression attenuated Nrf2 activation. IER3-deficient NCM460 cells exhibited reduced reactive oxygen species levels, indicating increased antioxidative protection, as well as lower sensitivity to TRAIL or anticancer drug-induced apoptosis and greater clonogenicity. Knockdown of Nrf2 expression reversed these IER3-dependent effects. Further, the enhancing effect of IER3 deficiency on Nrf2 activity relates to the control of the inhibitory tyrosine kinase Fyn by the PI3K/Akt pathway. Thus, the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 or knockdown of Akt or Fyn expression abrogated the impact of IER3 deficiency on Nrf2 activity. In conclusion, the interference of IER3 with the PI3K/Akt-Fyn pathway represents a novel mechanism of Nrf2 regulation that may get lost in tumors and by which IER3 exerts its stress-adaptive and tumor-suppressive activity.

Introduction

Chronic inflammation is a major risk factor for cancer including colorectal cancer. It is meanwhile widely accepted that the persistent exposure of epithelial cells, such as enterocytes, to an inflammatory environment leads to molecular alterations that favor tumor development, e.g. in colitis-associated cancer (1, 2). A wide array of inflammatory cells are involved in this process secreting cytokines and chemokines, e.g. TNF-α or IL-6, which affect the epithelial integrity and phenotype. In addition, inflammation-associated carcinogenesis is initiated quite early by genetic alterations resulting from oxidative damage during chronic inflammation (3, 4) as well as by adaptive signaling pathways engaged by the stressed epithelium to cope with the oxidative burden. These pathways include the activation of the antioxidative transcription factor nuclear factor-E2 related factor-2 (Nrf2).4 Acting mainly as a key regulator of the cellular response to oxidative and metabolic stress (5), Nrf2 induces the expression of a great number of antioxidative and phase II enzymes as well as a number of genes involved in cell growth and survival (6). Thus, Nrf2 confers protection from early damage during inflammation, e.g. in DSS-induced colitis and prevents colorectal carcinogenesis upon DSS/azoxymethane treatment (7). However, based on the wide spectrum of its actions and the cellular context, Nrf2 has a dual role in cancer (8).

On the one hand, Nrf2 has gained attention in chemoprevention because activation of Nrf2 by certain antioxidants such as sulforaphane and oltipraz leads to protection from toxic DNA damage and thereby from carcinogen-induced tumorigenesis (9). On the other hand, evidence has accumulated that Nrf2 exhibits also profound protumorigenic activity (10, 11), and a number of malignant tumors, including colonic (12–14) and pancreatic (15, 16) cancer, are known to exhibit an amplified activity of Nrf2.

Among the mechanisms leading to activation of Nrf2 in tumor cells, certain genetic and epigenetic alterations have been described, affecting mainly the regulation of Nrf2 by its inhibitor Kelch-like-Ech-associated protein-1 (Keap1) (17–20). Metabolic effects, e.g. through down-regulation of the citric acid cycle enzyme fumarate hydratase (21, 22) and deregulated signaling pathways quite common in tumorigenesis, also relate to Nrf2 activation, e.g. the PI3K/Akt pathway that controls the late induction phase of Nrf2 through interference with its Fyn kinase-dependent nuclear export (23, 24). In addition, persistent oxidative stress leads to an up-regulation of Nrf2 expression/activity, as well (25), a condition that exists in epithetlial cells exposed to an inflammatory environment (26), e.g. in colonocytes from inflammatory bowel disease patients.

Using the well established DSS-colitis model in mice we have recently observed a dramatic gain in the inflammatory phenotype of the diseased colon (27) when mice are lacking the stress-inducible, multifunctional early response gene immediate early response-3 (IER3) (28, 29), also known as IEX-1 gene (30). Besides markedly increased leukocyte infiltrations in the colonic mucosa of DSS-treated mice, an aggravated impact on the crypt architecture and colonocyte morphology was noted if the Ier3 gene had been deleted (27) along with a greater incidence of tumor formation. In accordance with previous findings, the lack of IER3 expression is associated with a deregulation of the NF-κB and PI3K/Akt pathways (31–33) thereby impacting on tumorigenesis. A number of tumors (34–36) negatively correlate with IER3 expression thus pointing a tumor-suppressive action of this gene. Nambiar et al. (36) reported down-regulation of colonic IER3 expression in a mouse colorectal cancer model as well as in patients with advanced colorectal cancer. IER3 has therefore gained attention during the last couple of years in terms of its use as novel biomarker in certain types of cancer (37, 38), particularly relating to its profound and variable effects on chronic inflammation and inflammatory carcinogenesis (27, 39, 40).

Addressing the involvement of Nrf2 in these processes, e.g. in colitis-associated cancer, we were interested whether IER3 affects Nrf2 activation and thereby adds to the adaptation of epithelial cells to oxidative stress, along with phenotype alterations paving the way for carcinogenesis. Cell culture-based studies and experiments with Ier3 knock-out mice demonstrate that IER3 controls Nrf2 activation in colonic epithelial cells and thereby cellular protection and survival. Accordingly, the loss of IER3 expression relates to a marked increase of Nrf2 activity along with a stress-adapted phenotype of these cells. Our findings provide a novel mechanism of Nrf2 regulation that may be affected in disease and account for the protumorigenic potential of Nrf2 on the one hand, and for the tumor-suppressive effects of IER3 on the other hand.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Chemicals and Reagents

LY294002 was from Calbiochem, tBHQ and SFN from Sigma, Killer-TRAIL from Enzo Life-Science/Alexis (Lörrach, Germany), and etoposide (Vepesid) from Bristol-Myers/Squibb.

Cell Lines and Animals

Human NCM460 colonocytes (41) were purchased from INCELL Corp. (San Antonio, TX) and cultured as described (12). For the isolation of distal colonic organ cultures, gly96/Ier3−/− mice on C57BL/6 background or their wild-type littermates were used (27, 42).

Colon Organ Culture

A segment of the distal colon from gly96/Ier3−/− mice on C57BL/6 background or from their gly96/Ier3+/+ counterparts was removed, cut open longitudinally, and washed in PBS containing 100 μg/ml penicillin (Sigma) and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Sigma). The colon was then further cut into segments of 1 cm2, placed and incubated in 24-well flat-bottom culture plates containing 1 ml of fresh RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with penicillin and streptomycin at 37 °C for 16–24 h. Then, tBHQ was administered for various periods, or not, at a dose of 50 μm. Cultured cells were then subjected to preparation of nuclear extracts, total cell lysates, or RNA, as described (27). For validation of equal viability, colon organ cultures were analyzed in parallel by the MTS assay (CellTiter 96®; Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. OD values were normalized to cellular protein content of each culture determined by the DC assay (Bio-Rad).

Western Blotting

Nuclear extracts or total cell lysates were prepared as described before (27, 43). After electrophoresis and semidry electroblotting onto PVDF membranes, the following primary antibodies were used for immunodetection: Nrf2 (Abcam); NQO1, GCLC, IER3, Hsp90, and lamin A/C (Santa Cruz Biotechnology); tubulin (Sigma) or Fyn; Akt, PARP1, and caspase-3 (Cell Signaling) at 1:500- to 1:1000-fold dilutions in blocking buffer (5% (w/v) nonfat milk powder in TBST (Tris-buffered saline (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, and 150 mm NaCl) plus 0.05% Tween 20), or P-Akt (Cell Signaling Technology) at a 1:1000 dilution in 5% (w/v) bovine serum albumin in TBST. After incubation overnight at 4 °C, blots were exposed to the appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) diluted (1:1000) in blocking buffer and developed using the Dura detection kit (Perbio Sciences, Bonn, Germany). Data acquisition was done with the Chemidoc-XRSTM gel documentation system (Bio-Rad) using Quantity One® software (Bio-Rad). Lamin A/C, tubulin, or Hsp90 served as loading controls.

RNA Preparation and Real-time PCR

Isolation of total RNA and reverse transcription into single-stranded cDNA were carried out as described (12). cDNA was subjected to real-time PCR (iCycler; Bio-Rad) using the SYBR Green assay (12) with gene-specific primers (all from Realtime Primers® via Biomol) at a final concentration of 0.2 μm. The cycling conditions were: 95 °C for 20 s/58 °C for 20 s/72 °C for 20s for 40 cycles.

shRNA Transfection and siRNA Treatment

NCM460 cells were stably transfected with an IER3 shRNA vector or the corresponding control shRNA vector (both from Qiagen) following the manufacturer's protocol and using puromycin (Sigma) selection at 0.5 μg/ml. The functionality of IER3 shRNA was verified by qPCR analysis of IER3 mRNA (see Fig. 3c). For siRNA (Qiagen) transfection, cells grown in 12-well plates were submitted to lipofection using 6 μl of the HiPerfect reagent (Qiagen) and 150 ng/well siRNA. Under these conditions, NCM460 shRNA cells were treated with negative control siRNA (SI1027280), Nrf2 siRNA (SI03246614), Akt siRNA (SI02757244), or Fyn siRNA (SI02654729).

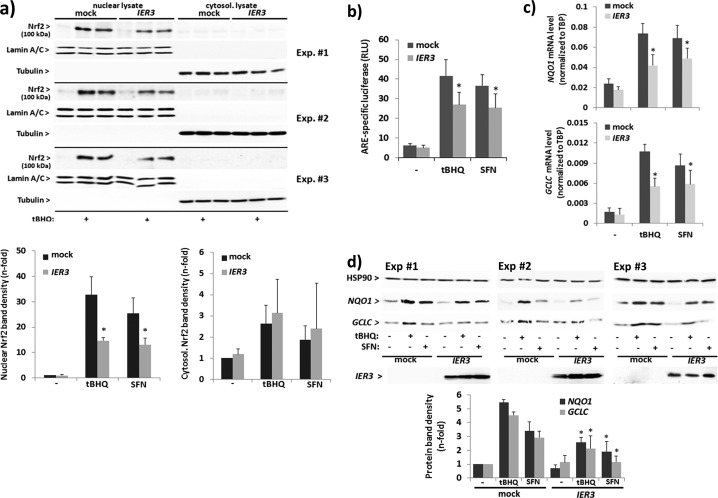

FIGURE 3.

IER3 interferes with Nrf2 activation in human NCM460 colonocytes. NCM460 cells were transfected with an IER3 expression vector or the empty vector (mock) and then analyzed for Nrf2 activation. a, nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts from untreated or tBHQ- (50 μm, 16 h) or SFN- (10 μm, 16 h) treated cells were analyzed by Nrf2 Western blotting (lamin A/C and tubulin, respectively, served as loading control). Three of six biological replicate experiments are shown from which n-fold band intensities of Nrf2 (100 kDa) were determined by densitometry analysis normalizing to the corresponding loading controls (mean ± S.D. (error bars), n = 6). b, ARE-Luc assays were conducted in IER3-transfected or untransfected cells subject of treatment (16 h) with 50 μm tBHQ or 10 μm SFN or not. Data are expressed as ARE-specific relative luciferase units (RLU) and represent the mean ± S.D., n = 4. c, NQO1 and GCLC mRNA levels were analyzed by qPCR (using TATA-binding protein (TBP) mRNA for normalization) in IER3-transfected or untransfected cells subjected to treatment (16 h) with 50 μm tBHQ or 10 μm SFN or not. Data represent the mean ± S.D., n = 4. d, total cell lysates from untreated or tBHQ- (50 μm, 24 h) or SFN- (10 μm, 24 h) treated cells were analyzed by Western blotting for NQO1 and GCLC as well as IER3 expression (Hsp90 served as loading control). Three of four biological replicate experiments are shown from which n-fold band intensities were determined by densitometry analysis normalizing to Hsp90 (mean ± S.D., n = 4). * indicates statistical significance between IER3 and mock transfectants.

Immunohistochemistry

Six-μm cryostat sections were mounted on uncovered glass slides, air-dried overnight at room temperature, fixed in chilled acetone (Merck) for 10 min, and air-dried again for 10 min. Then, slides were washed in PBS. To avoid nonspecific binding, sections were treated with 4% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Serva, Heidelberg, Germany) for 20 min followed by incubation with the monoclonal rabbit Ser40-phospho-Nrf2 antibody (Abcam) used at 1:200 dilution in 1% BSA/PBS (50). After primary antibody incubation (overnight, 4 °C), sections were washed three times in PBS and then treated with EnVision peroxidase conjugates (DakoCytomation, Hamburg, Germany) for 30 min. Afterward, sections were washed three times in PBS. Then, peroxidase substrate reaction was performed with the AEC peroxidase substrate kit (DakoCytomation) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Afterward, sections were washed in water, counterstained in 50% hemalaun (Merck), and mounted with glycerol gelatin. The same protocol was performed for negative controls using isotype-matched rabbit IgG. For TUNEL staining of apoptotic cells, the tissue sections were incubated with the in situ cell death detection enzyme/nucleotide mixture (Roche Diagnostics) for 1 h at 37 °C followed by the POD-converter for 30 min at 37 °C and then further processed as described above. For immunofluorescence microscopy, slides were incubated (1 h, room temperature) with a rat phycoerythrin-conjugated monoclonal F4/80 antibody (AbD Serotec, Düsseldorf, Germany, 1:100 dilution in 1% BSA/PBS) or a rabbit monoclonal P-Akt antibody (Cell Signalling, 1:100 dilution) followed by an anti-rabbit second antibody conjugated to Cy3 (1:100 dilution). Before examination, nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. The corresponding isotype-matched IgG antibodies were used as negative controls.

Plasmid Transfection

Cells were transfected with mock or IER3 expression plasmids (32) and with the control or ARE-Luc plasmids (SABioscience/Qiagen) using the Effectene transfection reagent (Qiagen) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Dual Luciferase Assay

ARE-driven reporter gene expression in cells was determined using a the Nrf2 pathway detection kit (SABioscience/Qiagen) and as described recently (12).

Caspase-3/-7 Activity Assay

Apoptosis induced by Killer-TRAIL or etoposide was determined by the measurement of caspase-3/-7 activity (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions and as described (12). All assays were done in duplicates. Caspase-3/-7 activity was normalized to the protein content of the analyzed cell lysates.

Determination of Intracellular ROS

Medium of cells was replaced by 1 ml of prewarmed PBS, and the cells were treated with 10 μm cellular ROS indicator 5-carboxy-2′,7′-dichlorodihydro-fluoresceine diacetate (c-H2DCF-DA; DCF) or the mitochondrial ROS (superoxide) detector MitoSOX Red (both from Invitrogen) dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide, or with the vehicle alone for 20 min at 37 °C. Then, the labeled NCM460 cells were incubated in OptiMEM (PAA Laboratories, Cölbe, Germany) for several hours at 37 °C. Fluorescence was measured with the Techan Infinite 200 microplate reader.

Colony Formation Assay

Cells were seeded at a density of 200 or 500 cells/well on a 6-well plate. After 2 days, medium was exchanged, supplemented with tBHQ or without. After 2–3 weeks of culture with one weekly medium exchange, cells were washed twice with PBS, then fixed with methanol/acetic acid (3:1) for 5 min and stained with 0.1% (w/v) crystal violet. Plates were photographed using the Chemidoc-XRSTM transiluminator. Colonies >0.25-mm diameter were counted. The plating efficiency was calculated as the ratio of colony number/cells initially seeded.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± S.D. and were analyzed by student's t test. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

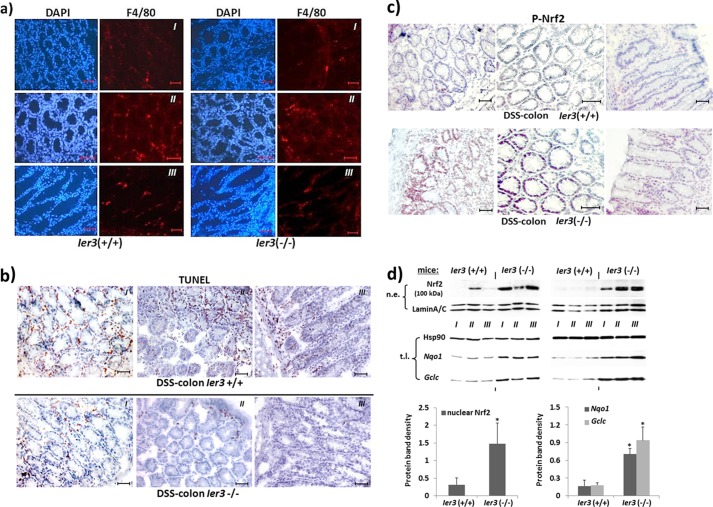

Greater Nrf2 Activation in the Colon of Ier3−/− Mice

To analyze the status of Nrf2 activation, tissue sections from the distal colon of DSS-treated Ier3+/+ and Ier3−/− mice exhibiting a similar extent of macrophage infiltration, as detected by anti-F4/80 immunofluorescent staining (Fig. 1a), but different amounts of apoptotic cells, as shown by TUNEL staining (Fig. 1b), were submitted to immunostaining with an antibody against activated (P-Ser40)-Nrf2. As shown in Fig. 1c, a much stronger staining in the crypt structures of DSS-treated Ier3−/− mice was observed compared with DSS-treated Ier3+/+ mice. This intensive staining is particularly seen in the nuclei of enterocytes within severely inflamed areas of the colonic mucosa, exhibiting intense staining for macrophages with F4/80 (Fig. 1a). The number of apoptotic crypt cells visualized by TUNEL staining (Fig. 1b) was lower in the colon tissue from Ier3−/− mice compared with Ier3+/+ mice. Next, nuclear extracts from distal colon tissue from DSS-treated Ier3−/− or Ier3+/+ mice were analyzed by Western blotting for the presence of Nrf2 protein, indicative of Nrf2 activation. As shown in Fig. 1d (top panel), nuclear extracts from DSS-treated Ier3-deficient mice contained much greater amounts of Nrf2 (appearing as a 100-kDa band) than the extracts from DSS-treated wild-type mice. Further, Western blot analysis detected greater expression level of the Nrf2 target genes Nqo1 and Gclc (Fig. 1d, middle panel) in Ier3−/− colonic tissue, thus indicating enhanced Nrf2 activation.

FIGURE 1.

Greater Nrf2 activity in the inflamed colon tissue of DSS-treated mice lacking Ier3 expression. a and b, cryostat sections of colon tissues from DSS-treated Ier3−/− or Ier3+/+ mice were submitted to immunofluorescent staining of the macrophage marker F4/80 to detect inflamed areas enriched for tissue macrophages (a) or to TUNEL staining for detection of apoptotic cells (b). Tissue stainings from three different animals (I–III) each genotype are shown; scale bars, 20 μm. c, cryostat sections were analyzed for Nrf2 activation by immunostaining with an antibody detecting activated (P-Ser40)-Nrf2. Tissue stainings from three different animals each genotype are shown; scale bars, 20 μm. d, two series of colon tissues from Ier3−/− or Ier3+/+ mice (three animals either (I–III)) subjects of chronic DSS colitis were analyzed by Western blotting for Nrf2 protein level in nuclear extracts (n.e., top panel), or for the expression of the Nrf2 target genes Nqo1 and Gclc in total cell lysates (t.l., middle panel). Lamin A/C and Hsp90 were used as loading controls. Protein band intensities were determined by densitometry analysis (bottom panel) normalizing to the corresponding loading controls (mean ± S.D. (error bars), n = 6).

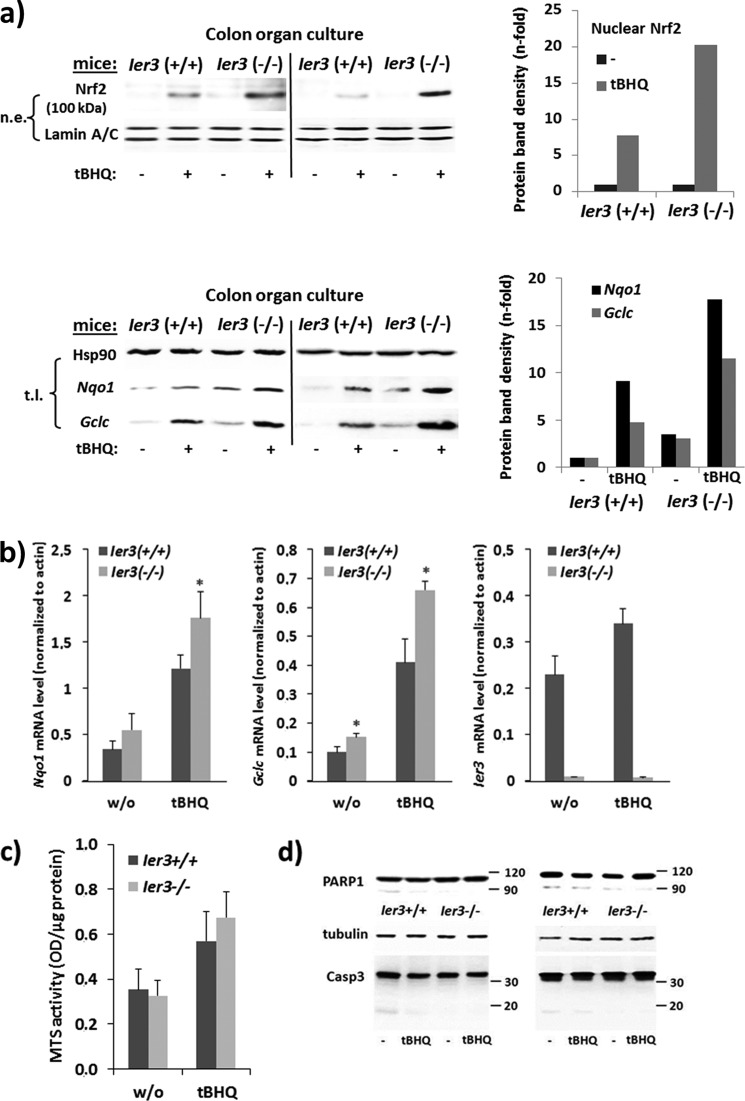

To confirm greater Nrf2 activation in Ier3-deficient tissue, colon organ cultures from untreated Ier3−/− or Ier3+/+ mice were treated with the Nrf2 inducer tBHQ (50 μm) for 16 h. As shown in Fig. 2a, an increase of Nrf2 protein level is seen in nuclear extracts after tBHQ treatment that was stronger in the absence of Ier3 expression. Moreover, Western blotting and qPCR analyses detected expression level of the Nrf2 target genes Nqo1 and Gclc (Fig. 2, a and b), which were greater in Ier3−/− than in Ier3+/+ colonic cells.

FIGURE 2.

Ier3 deficiency enhances Nrf2 activation in murine colonic tissue. Colon organ cultures from untreated Ier3−/− or Ier3+/+ mice (data from two independent experiments are shown) were subjected to treatment with 50 μm tBHQ for 16 h or not. a, nuclear extracts (n.e., upper panel) were analyzed by Western blotting for Nrf2 protein level using lamin A/C as loading control, or total cell lysates (t.l., lower panel) were analyzed for Nqo1 and Gclc (Hsp90 as loading control). n-fold protein band intensities were determined by densitometry analysis normalizing to the corresponding loading controls. b, total RNA samples were submitted to RT-qPCR analyses of Gclc, Nqo1, and Ier3 mRNA levels normalized to β-actin mRNA (molecular mass ± S.D. (error bars), n = 4). * indicates statistical significance between the two genotypes. c and d, colon organ cultures were analyzed for viability by MTS staining for 2 h, and A490 nm values were normalized for protein content (mean ± S.D., n = 4) or by Western blotting (results from two independent experiments) for PARP1 and caspase-3 protein expression using tubulin as loading control.

MTS assay revealed that the viability of colonic tissues in the untreated organ culture was not significantly different between both mouse genotypes (Fig. 2c), and after treatment with tBHQ a slightly greater number of viable cells was present in the culture from Ier3−/− mice. Likewise, PARP1 and caspase-3 Western blots revealed only slight differences in apoptosis during colon organ culture (Fig. 2d) and indicated somewhat lower apoptosis in the Ier3−/− colonic culture.

Nrf2 Activation Is Controlled by IER3 in Human Colonic Epithelial Cells

To verify that IER3 controls Nrf2 activation in human colonic epithelial cells, representing a mechanism that may be affected in early carcinogenesis, and to study the impact of IER3 directly, we made use of the human colonic epithelial cell line NCM460. Overexpression of IER3 in NCM460 cells strongly suppressed the activation of Nrf2, as shown by decreased nuclear Nrf2 protein level, both in unstimulated and tBHQ-stimulated cells (Fig. 3a). In contrast, no such differences were seen when analyzing Nrf2 protein level in cytosolic extracts (Fig. 3a). ARE-luciferase assays detected a marked decrease in the induction of Nrf2-driven transcription by tBHQ (16 h) when NCM460 cells overexpressed IER3 (Fig. 3b). Under these conditions, the expression of the Nrf2 target genes NQO1 and GCLC was also decreased, as shown by qPCR and Western blot analyses (Fig. 3, c and d). When investigating SFN as another potent Nrf2 inducer, a similar inhibitory effect of IER3 overexpression on Nrf2 activation was noted (Fig. 3, a–d).

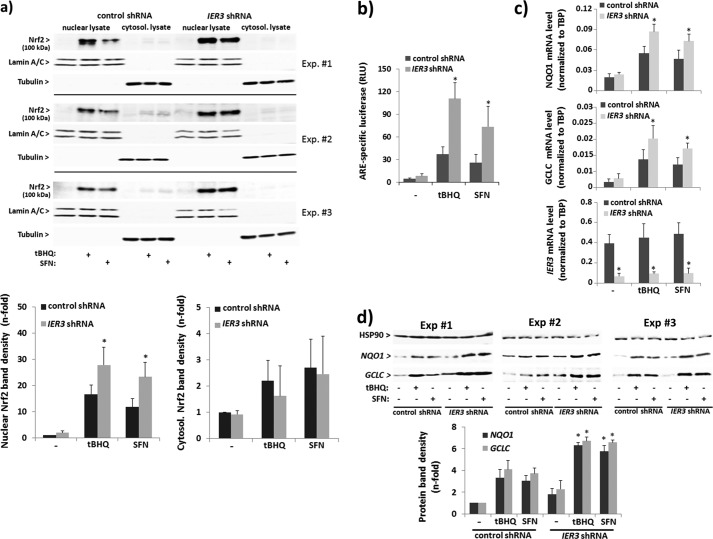

To study the effect of IER3 deficiency on Nrf2 activation, NCM460 cells were used stably expressing IER3-shRNA. As shown in Fig. 4, the induction of Nrf2 in NCM460 cells by tBHQ was increased in IER3-deficient cells. Western blotting detected greater amounts of Nrf2 protein in nuclear extracts from IER3-shRNA-expressing NCM460 cells compared with control shRNA NCM460 cells (Fig. 4a). ARE-luciferase reporter assays revealed an enhanced Nrf2 activation in NCM460 cells expressing IER3 shRNA (Fig. 4b), and qPCR or Western blot analysis revealed a more pronounced induction of the Nrf2 target genes NQO1 and GCLC by tBHQ (Fig. 4, c and d). Likewise, the effect of SFN on Nrf2 activation and Nrf2 target gene expression was enhanced by the IER3 deficiency in NCM460 cells (Fig. 4, a–d), as well.

FIGURE 4.

Increased Nrf2 activation in human NCM460 colonocytes with suppressed IER3 expression. NCM460 stably transfected with an IER3-shRNA or control-shRNA vector were analyzed for Nrf2 activation. a, nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts from untreated or tBHQ- (50 μm, 16 h) or SFN- (10 μm, 16 h) treated cells were analyzed by Nrf2 Western blotting (lamin A/C and tubulin, respectively, served as loading control). Three of six biological replicate experiments are shown from which n-fold band intensities of Nrf2 (100 kDa) were determined by densitometry analysis normalizing to the corresponding loading controls (mean ± S.D. (error bars), n = 6). b, ARE-luciferase assays were conducted in IER3 shRNA- or control shRNA-transfected cells subjected to treatment (16 h) with 50 μm tBHQ or 10 μm SFN or not. Data are expressed as ARE-specific relative luciferase units (RLU) and represent the mean ± S.D., n = 4. c, NQO1 and GCLC as well as IER3 mRNA levels were analyzed by qPCR (using TATA-binding protein (TBP) mRNA for normalization) in IER3 shRNA- or control shRNA-transfected cells subjected to treatment (16 h) with 50 μm tBHQ or 10 μm SFN or not. Data represent the mean ± S.D., n = 6. d, total cell lysates from untreated or tBHQ- (50 μm, 24 h) or SFN- (10 μm, 24 h) treated cells were analyzed by Western blot for NQO1 and GCLC expression (Hsp90 served as loading control). Three of six biological replicate experiments are shown from which n-fold band intensities were determined by densitometry analysis normalizing to Hsp90 (mean ± S.D., n = 6).* indicates statistical significance between IER3 shRNA- and control shRNA-expressing cells.

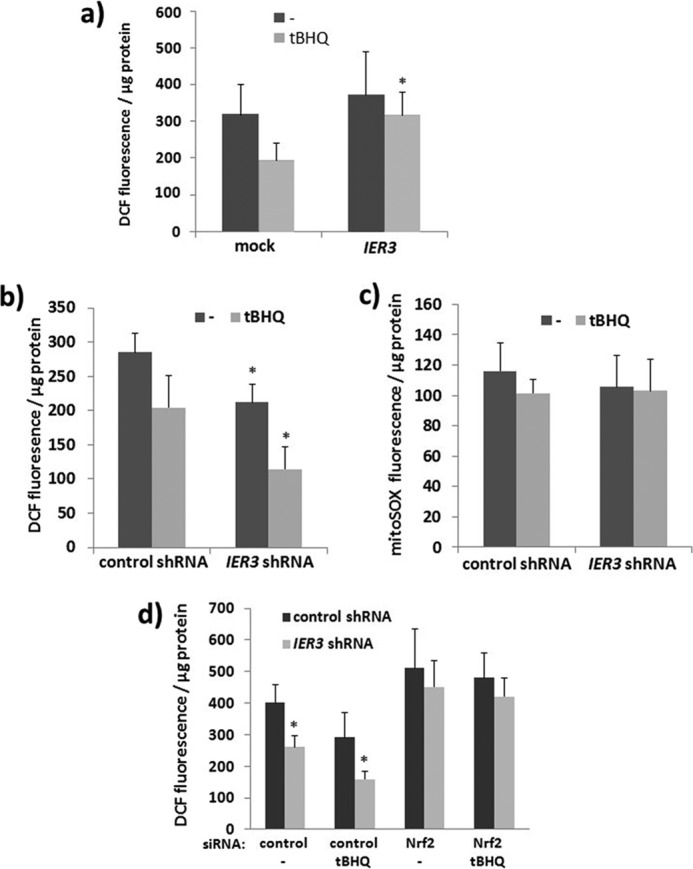

IER3-deficient NCM460 Cells Exhibit Lower Intracellular ROS Levels Depending on Nrf2

The increased activation of Nrf2 in IER3-deficient cells could be either the consequence of an enhanced ROS formation through the previously reported modulatory effect of IER3 on the respiratory chain (44), or in turn, the greater Nrf2 activity along with the expression of antioxidative target genes may neutralize intracellular ROS. We therefore analyzed the amount of intracellular ROS by staining with DCF. As shown in Fig. 5a, NCM460 cells subject of tBHQ treatment (24 h) exhibited decreased DCF staining compared with cells without tBHQ. When overexpressing IER3, this tBHQ-dependent decrease of DCF staining in NCM460 cells was abrogated, indicating interference of IER3 with cellular ROS neutralization. In support of this, IER3 shRNA-expressing NCM460 cells exhibited lower staining with DCF compared with control shRNA NCM460 cells (Fig. 5b). When preincubated with tBHQ for 24 h, DCF staining was further decreased in NCM460 IER3 shRNA cells more strongly than in control cells (Fig. 5b). No such effects were observed in NCM460 shRNA transfectants when stained with MitoSOX Red, a dye that detects exclusively mitochondrial superoxides generated through the respiratory chain (Fig. 5c). Thus, the effect of IER3 deficiency primarily affects the antioxidative and thereby ROS-neutralizing activity exerted by Nrf2. This is underscored by the finding that the knockdown of Nrf2 by siRNA elevated the DCF staining intensity in NCM460 IER3 shRNA cells and abrogated the enhanced neutralizing effect of tBHQ in these cells (Fig. 5d) compared with control shRNA cells.

FIGURE 5.

Decreased ROS level in human NCM460 colonocytes with suppressed IER3 expression depending on Nrf2. a–c, NCM460 cells overexpressing IER3 or not (mock) (a) or NCM460 cells stably transfected with control or IER3 shRNA (b and c) were subjected to tBHQ treatment (24 h), or not, and then stained with cH2DCFdA to detect intracellular ROS (a and b) or with MitoSOX Red to detect mitochondrial ROS (c). Fluorescence was determined 4 h later; data represent the mean ± S.D. (error bars), n = 4. d, NCM460 stably transfected with control or IER3 shRNA were treated with control or Nrf2 siRNA for 40 h. Then, tBHQ was added, or not, for 24 h followed by cH2DCFdA staining and fluorescence measurement 4 h later; data represent the mean ± S.D., n = 6. * indicates statistical significance between the IER3 shRNA- and control shRNA-expressing cells.

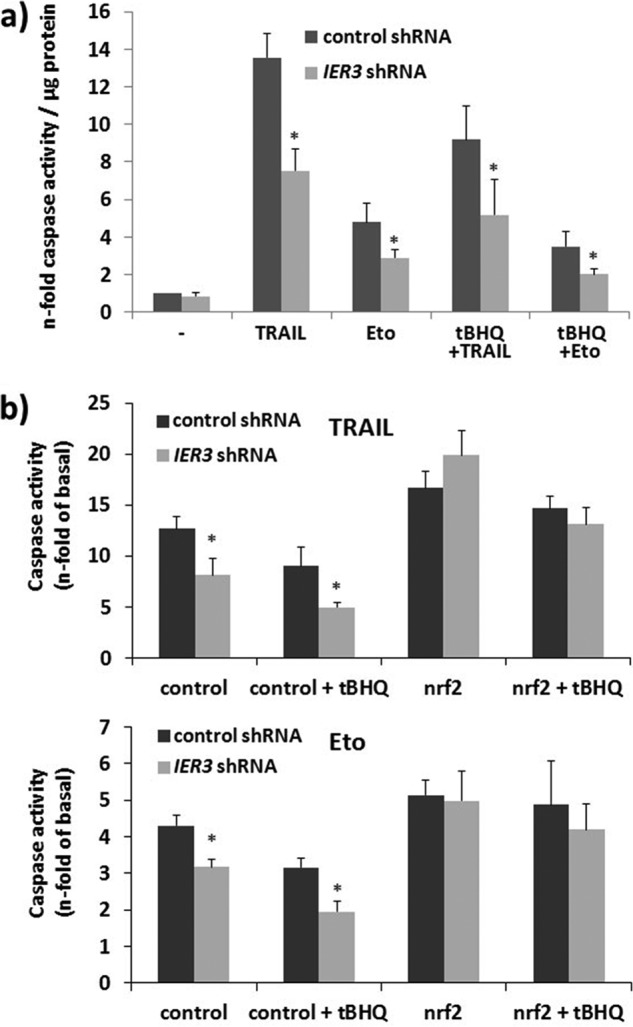

NCM460 Cells Gain Protection from Apoptosis Induction through IER3 Deficiency in a Nrf2-dependent Fashion

By means of caspase-3/-7 assays it could be shown that NCM460 cells stably expressing IER3 shRNA are less sensitive to TRAIL or anticancer drug (etoposide)-induced apoptosis compared with control shRNA-expressing NCM460 cells. In the presence of tBHQ, the sensitivity to both apoptotic stimuli was more strongly reduced in IER3 shRNA-expressing NCM460 cells than in control shRNA cells (Fig. 6a). When knocking down Nrf2 expression in the NCM460 shRNA tranfectants by siRNA, the sensitivity to both apoptotic stimuli was enhanced, in particular in IER3 shRNA NCM460 cells, and the more resistant phenotype of IER3 shRNA-expressing NCM460 cells could not be appreciated any more (Fig. 6b).

FIGURE 6.

Greater Nrf2 activity in IER3-deficient human NCM460 colonocytes confers apoptosis protection. a, NCM460 cells stably transfected with control or IER3 shRNA and subjected to tBHQ treatment (24 h), or not, were left untreated or treated with either 10 ng/ml TRAIL (8 h) or 20 μg/ml etoposide (24 h). Caspase assays were conducted, and apoptosis was expressed as n-fold of untreated, mean ± S.D. (error bars); n = 4. b, IER3 shRNA or control shRNA NCM460 cells were treated with control or Nrf2 siRNA. After 24 h, tBHQ was added, or not, followed by TRAIL or etoposide treatment 24 h later. Caspase assays were conducted and apoptosis was expressed as n-fold of untreated, mean ± S.D.; n = 4. * indicates statistical significance between the IER3 shRNA- and control shRNA-expressing cells.

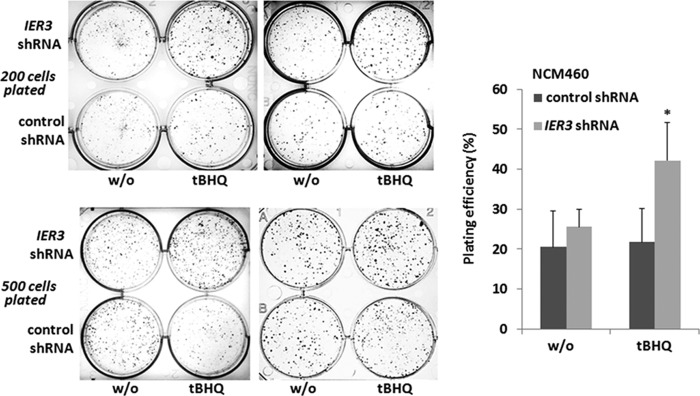

Elevated Colony Formation of NCM460 Cells through IER3 Deficiency in a Nrf2-dependent Fashion

Clonogenicity assays (Fig. 7) revealed that NCM460 cells stably transfected with IER3 or control shRNA exhibit clonal growth to a similar extent (plating efficiency 21.8 ± 8.4 versus 20.6 ± 9.0%) when cultured without additive. When treated with tBHQ, IER3 shRNA cells were capable of forming more colonies than control shRNA NCM460 cells (plating efficiency 42.1 ± 9.6 versus 25.6 ± 4.3%).

FIGURE 7.

Increased clonal growth of IER3-deficient NCM460 cells. NCM460 cells stably transfected with control or IER3 shRNA were seeded at a density of 200 or 500 cells/well on a 6-well plate and cultured for 1–2 weeks in the absence or presence of 50 μm tBHQ. Then, cells were fixed and stained with crystal violet. Visualized colonies with a diameter of >0.25 mm were counted, and the plating efficiency was calculated. Representative results (left panel) of four independent experiments performed in duplicates are shown, and the evaluation was carried out using the mean values ± S.D. (error bars, right panel) from these duplicate experiments. * indicates statistical significance between the IER3 shRNA- and control shRNA-expressing cells.

The Greater Nrf2 Activity in IER3-deficient Cells Depends on the PI3K/Akt Pathway

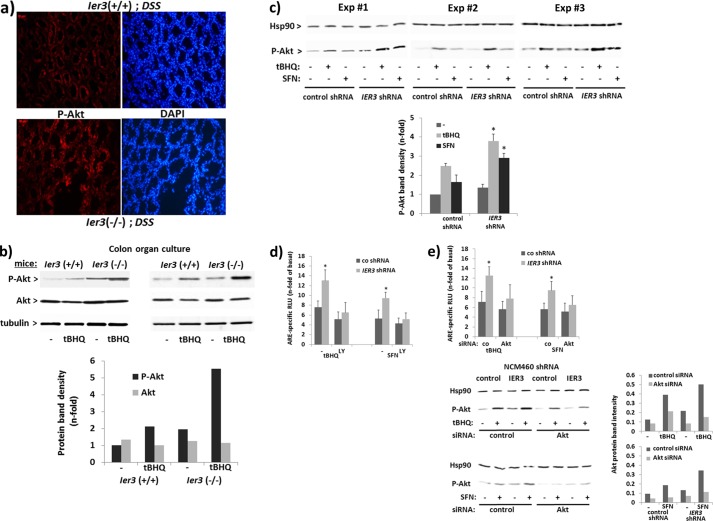

In accordance with previous findings (33), IER3 affects Akt activation. Immunofluoresence microscopy detected stronger staining of P-Akt in the crypt structures of DSS-treated Ier3−/− mice compared with DSS-treated Ier3+/+ mice (Fig. 8a). Moreover, Western blot analysis detected increased P-Akt levels in total cell extracts of colonic epithelial cells from organ cultures of Ier3−/− mice (Fig. 8b) either subject to no treatment or tBHQ treatment (4 h) compared with colon organ culture from Ier3+/+ mice. Greater levels of P-Akt were similarly seen in tBHQ-treated as well as in untreated NCM460 cells when expressing IER3-shRNA (Fig. 8c), thus confirming the modulating effect of IER3 on the PI3K/Akt pathway. An increased P-Akt level was also seen in IER3-deficient cells after SFN treatment (Fig. 8c) even though SFN per se does not induce Akt phosphorylation that much, as seen in control shRNA NCM460 cells. To elucidate whether the enhanced Nrf2 activity in IER3-deficient cells relates to the PI3K/Akt pathway, ARE-luciferase assays were conducted. When treated with the PI3K inhibitor LY294002, the enhancement of Nrf2 induction in IER3-shRNA NCM460 cells was diminished as shown by the decreased ARE-dependent luciferase levels (Fig. 8d) which did not differ between both cell lines any more. Likewise, after treatment with Akt-siRNA, the increasing effect of the IER3 deficiency in NCM460 cells on Nrf2-dependent luciferase expression was much less pronounced compared with control siRNA-treated cells (Fig. 8e).

FIGURE 8.

Elevated Akt phosphorylation in IER3-deficient murine or human colonocytes and Akt dependence of the IER3 effect on Nrf2 activation. a, tissue sections from DSS-treated Ier3−/− or Ier3+/+mice were submitted to P-Akt immunofluorescence staining and DAPI counterstaining. b, colon organ cultures from untreated Ier3−/− or Ier3+/+ mice (data from two independent experiments are shown) were treated with 50 μm tBHQ, and cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting detecting phospho-Akt, Akt, and tubulin. n-fold protein band intensities of Akt and P-Akt were determined by densitometry analysis normalizing to tubulin. c, NCM460 cells stably transfected with control or IER3 shRNA were incubated with 50 μm tBHQ or 10 μm SFN for 4 h or not. Cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting for P-Akt (Hsp90 served as loading control) and three replicate of four experiments are shown. n-fold protein band intensities of P-Akt (lower panel) were determined by densitometry analysis normalizing to the Hsp90 (mean ± S.D. (error bars); n = 4). d and e, ARE-Luc assays were conducted with NCM460 cells stably transfected with control or IER3 shRNA and treated with 50 μm tBHQ or 10 μm SFN for 16 h, or not, either preincubated with 25 μm LY294002 for 1 h or not (d) or following pretreatment with Akt or control (co) siRNA for 48 h (e). The knockdown was verified by Western blotting and protein band densitometry (lower panel). Data are expressed as n-fold ARE-specific relative luciferase units (RLU) and represent the mean ± S.D., n = 4. * indicates statistical significance between the IER3 shRNA- and control shRNA-expressing cells.

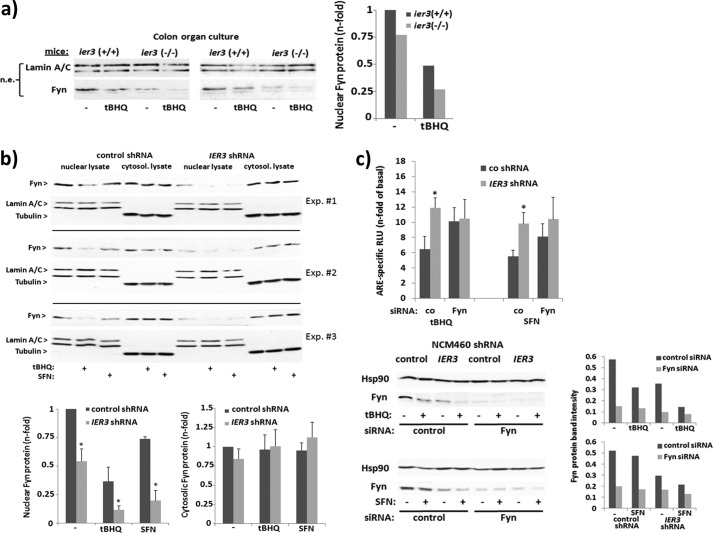

The Tyrosine Kinase Fyn Relates to the Impact of the IER3 Deficiency on Nrf2 Activation

Akt plays an important role in the late phase of Nrf2 activation through inhibition of the nuclear export of Nrf2 that is promoted by the tyrosine kinase Fyn (45). As shown by Western blot analysis, nuclear extracts of tBHQ-treated (8 h) or untreated colon organ cultures from Ier3−/− mice contain less Fyn protein than nuclear extracts of colon organ cultures from Ier3+/+ mice (Fig. 9a). Likewise, nuclear Fyn protein level were decreased in IER3 shRNA NCM460 cells compared with control shRNA NCM460 (Fig. 9b). This was seen in untreated as well as in tBHQ- or SFN-treated (8 h) cells when Fyn reaccumulated in the nuclei at a greater level. Therefore, we next elucidated whether inhibition of Fyn abrogates the stronger Nrf2 activity in IER3-deficient NCM460 cells. As shown by ARE-luciferase assay, the siRNA-mediated knockdown of Fyn increased the Nrf2 activity in tBHQ- or SFN-treated (16 h) control shRNA NCM460 cells (Fig. 9c), but not in IER3 shRNA NCM460 cells. Most notably, the greater Nrf2 activity in IER3-deficient NCM460 cells compared with IER3-proficient cells was much less pronounced after Fyn siRNA treatment (Fig. 9c).

FIGURE 9.

IER3 deficiency affects the nuclear accumulation of Fyn and its inhibitory effect on Nrf2 activation. a, colon organ cultures from untreated Ier3−/− or Ier3+/+ mice (data from two independent experiments are shown) were left untreated or were treated with 50 μm tBHQ for 8 h. Nuclear extracts were analyzed by Western blotting for Fyn (lamin A/C served as loading control). n-fold protein band intensities were determined by densitometry analysis normalizing to the corresponding loading control. b, nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts from untreated or tBHQ- (50 μm, 8 h) or SFN- (10 μm, 8 h) treated cells were analyzed by Fyn Western blotting (lamin A/C and tubulin, respectively, served as loading control). Three of six biological replicate experiments are shown from which n-fold band intensities of Fyn were determined by densitometry analysis normalizing to the corresponding loading controls (mean ± S.D. (error bars), n = 6). c, after pretreatment with Fyn or control (co) siRNA for 48 h, ARE-Luc assays were conducted with NCM460 cells stably transfected with control or IER3 shRNA and incubated with 50 μm tBHQ or 10 μm SFN for 16 h, or not. The knockdown was verified by Western blotting and protein band densitometry (lower panel). Data are expressed as n-fold ARE-specific relative luciferase units (RLU) and represent the mean ± S.D., n = 4. * indicates statistical significance between the IER3 shRNA- and control shRNA-expressing cells.

DISCUSSION

In addition to certain genetic alterations (3, 4), colitis-associated carcinogenesis involves many other molecular events taking place in the colonic epithelium which can initiate malignant transformation (2). Among these, Nrf2 has an important role in switching a normal and homeostatic phenotype into a malignant one. Even though Nrf2 has beneficial effects in anticancer protection through its antioxidative and detoxifying activity which is the rationale for current attempts of using Nrf2 induction in chemoprevention (9), this transcription factor exerts also considerable tumor promoting effects when being persistently activated (11, 46). In fact, tumor cells gain profound antiapoptotic protection and growth advantages from persistent Nrf2 activation, relying on the wide spectrum of cytoprotective target genes of Nrf2 as well as genes involved in the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway (12, 47, 48). In common with many other tumor entities, colorectal cancer cells are characterized by higher Nrf2 activity and exhibit Nrf2-dependent resistance to death ligands and anticancer drugs (12, 26, 49).

Still, the mechanisms leading to deregulated Nrf2 activity in tumor cells are not completely understood. Besides established gene mutations or epigenetic alterations affecting the Nrf2 inhibitory protein Keap1 or Nrf2 directly (17, 18), metabolic conditions and persistent oxidative stress play a role, as well (25, 50). During the latter, certain signaling pathways are involved, e.g. the PI3K/Akt pathway. An amplification of this pathway occurs, e.g. through mutations of the PTEN tumor suppressor or forced Ras/Raf and ERK1/2 activities. Another mechanism in this context relies on the control of the PI3K/Akt pathway by the stress response gene IER3 (33). As we demonstrated in this study, IER3-deficient cells (here NCM460 colonocytes or murine colonic tissue) are characterized by an enhanced level of P-Akt, and a consequence of this Akt amplification is an increased activation of Nrf2 that manifests particularly during a persistent oxidative challenge, e.g. during chronic inflammation. Accordingly, this IER3-dependent control of Nrf2 activation is seen in colonic tissue from mice suffering from DSS colitis. Whereas in Ier3-proficient mice the disease phenotype is mild, the animals with abrogated Ier3 expression had a more severe inflammatory disease activity (27).

Besides an amplified NF-κB activity found in the diseased tissues (27) we now detected also an exaggerated activation of Nrf2 if Ier3 expression had been ablated. This increasing effect through the Ier3 deficiency on Nrf2 is not merely an indirect one resulting from the stronger inflammatory/oxidative stress, but is obviously caused by the direct interference of Ier3 with the activation of Nrf2. Our results indicate that the control of Nrf2 activation by IER3 relates to its already documented negative impact on Akt (33), and through the inhibition of Akt, IER3 favors the inhibitory effect of Fyn on Nrf2 activation (24, 45). As we could demonstrate in human NCM460 colonocytes, the activation status of Nrf2 is clearly affected by IER3 expression. The impact of IER3 was noted with the activation of Nrf2 by tBHQ which itself increases the phosphorylation of Akt, but the modulatory effect of IER3 was also noted when analyzing SFN as Nrf2 activator which is rather a weak inducer or sometimes even an inhibitor of Akt (51, 52). Thus, IER3 provides a general control of Nrf2 activation through its impact on Akt, and IER3 deficiency amplifies Nrf2 activators which themselves do not substantially affect Akt.

Even though Nrf2 is primarily protective from DSS-induced colitis (7), avoiding early tissue damage and thereby colitis-associated cancer, its persistent activation later on may be detrimental and protumorigenic through Nrf2-dependent stress adaptation of the colonic epithelium. In this way, IER3 modulates a signal pathway having a crucial role in oncogenesis, and a loss of this modulation through IER3 deficiency may contribute to cancer initiation. This may apply also to other inflammation-induced cancers, e.g. pancreatic cancer that could develop from chronic pancreatitis, as the Nrf2-modulating effect by IER3 was also observed in H6c7 pancreatic duct cells.5

In addition to the previously reported impact of IER3 on NF-κB activation, representing an inhibitory feedback loop (27, 32, 53, 54) and relying on a direct interaction with p65 as well as on altered turnover of IκBα, the interference with Nrf2 activation is another mechanism by which IER3 may dampen stress response signals coming up with inflammation. In fact, inflamed tissues are characterized by high level of IER3 expression (55), mainly through NF-κB-dependent induction through cytokines like TNF-α, and its expression then is part of a compensatory mechanism. A compromised function of IER3 or even the loss of its expression as it is evident in several types of cancer (28, 29), including colon cancer (36), would therefore unleash these pathways and favor a tumorigenic phenotype through the prosurvival effects of NF-κB and also of Nrf2 (11, 43, 56). This would be of particular importance as it has been recently reported that Nrf2 is a target gene of p65/p50 in leukemic cells (57), but we did not see an impact of IER3 on Nrf2 relating to this p65/RelA effect. Instead, representing itself a p65/p50 target gene (28, 31), IER3 delivers an inhibitory activity from NF-κB to Nrf2, an effect that might add to the recently reported (58) direct attenuation of Nrf2 by p65/RelA. On the other hand, NF-κB certainly triggers inflammatory stress, including ROS production, leading to Nrf2 activation (25, 59). Thus, IER3 as modulator of both NF-κB and Nrf2 would balance the cross-talk between both transcription factors, and a failure in this modulation contributes to oncogenesis initiated by chronic inflammation, e.g. in colitis-associated cancer. Given this unique function of IER3, its expression may indeed serve as valuable biomarker (37, 38) for the prognosis and responsiveness of certain types of cancer.

Acknowledgments

We thank Maike Witt and Iris Bauer for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by the Medical Faculty of the University of Kiel (to C. G., A. A., and H. S.), the German Research Society Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) (to H. S. and A. A.), and the DFG Cluster of Excellence Inflammation at Interfaces.

I. Stachel, S. Sebens, and H. Schäfer, unpublished data.

- Nrf2

- nuclear factor E2-related factor-2

- ARE

- antioxidant response element

- DCF

- 5-carboxy-2′,7′-dichlorodihydro-fluoresceine diacetate (c-H2DCF-DA)

- DSS

- dextran sodium sulfate

- GCLC

- glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit

- IER3

- immediate early 3

- IEX-1

- immediate early gene x-ray 1

- Keap1

- Kelch-like-Ech-associated protein-1

- Luc

- luciferase

- MTS

- 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium salt

- NQO1

- NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase 1

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- SFN

- sulforaphane

- tBHQ

- tertbutylhydroxyquinone

- TRAIL

- tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand.

REFERENCES

- 1. Clevers H. (2004) At the crossroads of inflammation and cancer. Cell 118, 671–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. O'Connor P. M., Lapointe T. K., Beck P. L., Buret A. G. (2010) Mechanisms by which inflammation may increase intestinal cancer risk in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 16, 1411–1420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Seril D. N., Liao J., Yang G. Y., Yang C. S. (2003) Oxidative stress and ulcerative colitis-associated carcinogenesis: studies in humans and animal models. Carcinogenesis 24, 353–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chang W. C., Coudry R. A., Clapper M. L., Zhang X., Williams K. L., Spittle C. S., Li T., Cooper H. S. (2007) Loss of p53 enhances the induction of colitis-associated neoplasia by dextran sulfate sodium. Carcinogenesis 28, 2375–2381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Osburn W. O., Kensler T. W. (2008) Nrf2 signaling: an adaptive response pathway for protection against environmental toxic insults. Mutat. Res. 659, 31–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kensler T. W., Wakabayashi N., Biswal S. (2007) Cell survival responses to environmental stresses via the Keap1-Nrf2-ARE pathway. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 47, 89–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Khor T. O., Huang M. T., Prawan A., Liu Y., Hao X., Yu S., Cheung W. K., Chan J. Y., Reddy B. S., Yang C. S., Kong A. N. (2008) Increased susceptibility of Nrf2 knockout mice to colitis-associated colorectal cancer. Cancer Prev. Res. 1, 187–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kensler T. W., Wakabayashi N. (2010) Nrf2: friend or foe for chemoprevention? Carcinogenesis 31, 90–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hayes J. D., McMahon M., Chowdhry S., Dinkova-Kostova A. T. (2010). Cancer chemoprevention mechanisms mediated through the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 13, 1713–1748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lau A., Villeneuve N. F., Sun Z., Wong P. K., Zhang D. D. (2008) Dual roles of Nrf2 in cancer. Pharmacol. Res. 58, 262–270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Reuter S., Gupta S. C., Chaturvedi M. M., Aggarwal B. B. (2010) Oxidative stress, inflammation, and cancer: how are they linked? Free Rad. Biol. Med. 49, 1603–1616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Arlt A., Bauer I., Schafmayer C., Tepel J., Müerköster S. S., Brosch M., Röder C., Kalthoff H., Hampe J., Moyer M. P., Fölsch U. R., Schäfer H. (2009) Increased proteasome subunit protein expression and proteasome activity in colon cancer relate to an enhanced activation of nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2). Oncogene 28, 3983–3996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kim T. H., Hur E. G., Kang S. J., Kim J. A., Thapa D., Lee Y. M., Ku S. K., Jung Y., Kwak M. K. (2011) NRF2 blockade suppresses colon tumor angiogenesis by inhibiting hypoxia-induced activation of HIF-1α. Cancer Res. 71, 2260–2275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chang L. C., Fan C. W., Tseng W. K., Chen J. R., Chein H. P., Hwang C. C., Hua C. C. (2013) Immunohistochemical study of the Nrf2 pathway in colorectal cancer: Nrf2 expression is closely correlated to Keap1 in the tumor and Bach1 in the normal tissue. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 21, 511–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hong Y. B., Kang H. J., Kwon S. Y., Kim H. J., Kwon K. Y., Cho C. H., Lee J. M., Kallakury B. V., Bae I. (2010) Nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2 regulates drug resistance in pancreatic cancer cells. Pancreas 39, 463–472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. DeNicola G. M., Karreth F. A., Humpton T. J., Gopinathan A., Wei C., Frese K., Mangal D., Yu K. H., Yeo C. J., Calhoun E. S., Scrimieri F., Winter J. M., Hruban R. H., Iacobuzio-Donahue C., Kern S. E., Blair I. A., Tuveson D. A. (2011) Oncogene-induced Nrf2 transcription promotes ROS detoxification and tumorigenesis. Nature 475, 106–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hayes J. D., McMahon M. (2009) NRF2 and KEAP1 mutations: permanent activation of an adaptive response in cancer. Trends Biochem. Sci. 34, 176–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yoo N. J., Kim H. R., Kim Y. R., An C. H., Lee S. H. (2012) Somatic mutations of the KEAP1 gene in common solid cancers. Histopathology 60, 943–952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang R., An J., Ji F., Jiao H., Sun H., Zhou D. (2008) Hypermethylation of the Keap1 gene in human lung cancer cell lines and lung cancer tissues. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 373, 151–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Eades G., Yang M., Ya Y., Zhang Y., Zhou Q. (2011) miR-200a regulates Nrf2 activation by targeting Keap1 mRNA in breast cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 40725–40733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Adam J., Hatipoglu E., O'Flaherty L., Ternette N., Sahgal N., Lockstone H., Baban D., Nye E., Stamp G. W., Wolhuter K., Stevens M., Fischer R., Carmeliet P., Maxwell P. H., Pugh C. W., Frizzell N., Soga T., Kessler B. M., El-Bahrawy M., Ratcliffe P. J., Pollard P. J. (2011) Renal cyst formation in Fh1-deficient mice is independent of the Hif/Phd pathway: roles for fumarate in KEAP1 succination and Nrf2 signaling. Cancer Cell 20, 524–537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kinch L., Grishin N. V., Brugarolas J. (2011) Succination of Keap1 and activation of Nrf2-dependent antioxidant pathways in FH-deficient papillary renal cell carcinoma type 2. Cancer Cell 20, 418–420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kaspar J. W., Jaiswal A. K. (2011) Tyrosine phosphorylation controls nuclear export of Fyn, allowing Nrf2 activation of cytoprotective gene expression. FASEB J. 25, 1076–1087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Niture S. K., Khatri R., Jaiswal A. K. (2013) Regulation of Nrf2-an update. Free Rad. Biol. Med. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Singh S., Vrishni S., Singh B.K., Rahman I., Kakkar P. (2010) Nrf2-ARE stress response mechanism: a control point in oxidative stress-mediated dysfunctions and chronic inflammatory diseases. Free Radic. Res. 44, 1267–1288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sebens S., Bauer I., Geismann C., Grage-Griebenow E., Ehlers S., Kruse M. L. (2011) Inflammatory macrophages induce NRF2-dependent proteasome activity in colonic NCM460 cells and thereby confer anti-apoptotic protection. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 40911–40921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sina C., Arlt A., Gavrilova O., Midtling E., Kruse M. L., Muerkoster S. S., Kumar R., Fölsch U. R., Schreiber S., Rosenstiel P., Schäfer H. (2010) Ablation of gly96/immediate early gene-X1 (gly96/iex-1) aggravates DSS-induced colitis in mice: role for gly96/iex-1 in the regulation of NF-κB. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 16, 320–331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Arlt A., Schäfer H. (2011) Role of the immediate early response 3 (IER3) gene in cellular stress response, inflammation and tumorigenesis. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 90, 545–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wu M. X. (2003) Roles of the stress-induced gene IEX-1 in regulation of cell death and oncogenesis. Apoptosis 8, 11–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kondratyev A. D., Chung K. N., Jung M. O. (1996) Identification and characterization of a radiation-inducible glycosylated human early response gene. Cancer Res. 56, 1498–1502 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Arlt A., Grobe O., Sieke A., Kruse M. L., Fölsch U. R., Schmidt W. E., Schäfer H. (2001) Expression of the NF-κB target gene IEX-1 (p22/PRG1) does not prevent cell death but instead triggers apoptosis in HeLa cells. Oncogene 20, 69–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Arlt A., Kruse M. L., Breitenbroich M., Gehrz A., Koc B., Minkenberg J., Fölsch U. R., Schäfer H. (2003) The early response gene IEX-1 attenuates NF-κB activation in 293 cells, a possible counter-regulatory process leading to enhanced cell death. Oncogene 22, 3343–3351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Osawa Y., Nagaki M., Banno Y., Brenner D. A., Nozawa Y., Moriwaki H., Nakashima S. (2003) Expression of the NF-κB target gene x-ray-inducible immediate early response factor-1 short enhances TNF-α-induced hepatocyte apoptosis by inhibiting Akt activation. J. Immunol. 170, 4053–4060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Han L., Geng L., Liu X., Shi H., He W., Wu M. X. (2011) Clinical significance of IEX-1 expression in ovarian carcinoma. Ultrastruct. Pathol. 35, 260–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sasada T., Azuma K., Hirai T., Hashida H., Kanai M., Yanagawa T., Takabayashi A. (2008) Prognostic significance of the immediate early response gene X-1 (IEX-1) expression in pancreatic cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 15, 609–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nambiar P. R., Nakanishi M., Gupta R., Cheung E., Firouzi A., Ma X. J., Flynn C., Dong M., Guda K., Levine J., Raja R., Achenie L., Rosenberg D. W. (2004) Genetic signatures of high- and low-risk aberrant crypt foci in a mouse model of sporadic colon cancer. Cancer Res. 64, 6394–6401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kapoor S. (2012) Emerging role of IEX-1 in tumor pathogenesis and prognosis. Ultrastruct. Pathol. 36, 285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wu M. X., Ustyugova I. V., Han L., Akilov O. E. (2013) Immediate early response gene X-1, a potential prognostic biomarker in cancers. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 17, 593–606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ustyugova I. V., Zhi L., Wu M. X. (2012) Reciprocal regulation of the survival and apoptosis of Th17 and Th1 cells in the colon. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 18, 333–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zhi L., Ustyugova I. V., Chen X., Zhang Q., Wu M. X. (2012) Enhanced Th17 differentiation and aggravated arthritis in IEX-1-deficient mice by mitochondrial reactive oxygen species-mediated signaling. J. Immunol. 189, 1639–1647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Moyer M. P., Manzano L. A., Merriman R. L., Stauffer J. S., Tanzer L. R. (1996) NCM460, a normal human colon mucosal epithelial cell line. In Vitro Cell Dev. Biol. Anim. 32, 315–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sommer S. L., Berndt T. J., Frank E., Patel J. B., Redfield M. M., Dong X., Griffin M. D., Grande J. P., van Deursen J. M., Sieck G. C., Romero J. C., Kumar R. (2006) Elevated blood pressure and cardiac hypertrophy after ablation of the gly96/IEX-1 gene. J. Appl. Physiol. 100, 707–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Müerköster S., Arlt A., Sipos B., Witt M., Grossmann M., Klöppel G., Kalthoff H., Fölsch U. R., Schäfer H. (2005) Increased expression of the E3-ubiquitin ligase receptor subunit βTRCP1 relates to constitutive NF-κB activation and chemoresistance in pancreatic carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 65, 1316–1324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Shen L., Zhi L., Hu W., Wu M. X. (2009) IEX-1 targets mitochondrial F1Fo-ATPase inhibitor for degradation. Cell Death Differ. 16, 603–612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jain A. K., Jaiswal A. K. (2007) GSK-3β acts upstream of Fyn kinase in regulation of nuclear export and degradation of NF-E2 related factor. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 16502–16510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zhang D. D. (2010) The Nrf2-Keap1-ARE signaling pathway: the regulation and dual function of Nrf2 in cancer. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 13, 1623–1626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kwak M. K., Wakabayashi N., Greenlaw J. L., Yamamoto M., Kensler T. W. (2003) Antioxidants enhance mammalian proteasome expression through the Keap1-Nrf2 signaling pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 8786–8794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Arlt A., Sebens S., Krebs S., Geismann C., Grossmann M., Kruse M. L., Schreiber S., Schäfer H. (2013) Inhibition of the Nrf2 transcription factor by the alkaloid trigonelline renders pancreatic cancer cells more susceptible to apoptosis through decreased proteasomal gene expression and proteasome activity. Oncogene 32, 4825–4835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Akhdar H., Loyer P., Rauch C., Corlu A., Guillouzo A., Morel F. (2009) Involvement of Nrf2 activation in resistance to 5-fluorouracil in human colon cancer HT-29 cells. Eur. J. Cancer 45, 2219–2227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ooi A., Wong J. C., Petillo D., Roossien D., Perrier-Trudova V., Whitten D., Min B. W., Tan M. H., Zhang Z., Yang X. J., Zhou M., Gardie B., Molinié V., Richard S., Tan P. H., Teh B. T., Furge K. A. (2011) An antioxidant response phenotype shared between hereditary and sporadic type 2 papillary renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell 20, 511–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Deng C., Tao R., Yu S. Z., Jin H. (2012) Sulforaphane protects against 6-hydroxydopamine-induced cytotoxicity by increasing expression of heme oxygenase-1 in a PI3K/Akt-dependent manner. Mol. Med. Rep. 5, 847–851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Leoncini E., Malaguti M., Angeloni C., Motori E., Fabbri D., Hrelia S. (2011) Cruciferous vegetable phytochemical sulforaphane affects phase II enzyme expression and activity in rat cardiomyocytes through modulation of Akt signaling pathway. J. Food Sci. 76, H175–H181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Arlt A., Rosenstiel P., Kruse M. L., Grohmann F., Minkenberg J., Perkins N. D., Fölsch U. R., Schreiber S., Schäfer H. (2008) IEX-1 directly interferes with RelA/p65-dependent transactivation and regulation of apoptosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1783, 941–952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Billmann-Born S., Till A., Arlt A., Lipinski S., Sina C., Latiano A., Annese V., Häsler R., Kerick M., Manke T., Seegert D., Hanidu A., Schäfer H., van Heel D., Li J., Schreiber S., Rosenstiel P. (2011) Genome-wide expression profiling identifies an impairment of negative feed-back signals in the Crohn disease-associated NOD2 variant L1007fsinsC1. J. Immunol. 186, 4027–4038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Costello C. M., Mah N., Häsler R., Rosenstiel P., Waetzig G. H., Hahn A., Lu T., Gurbuz Y., Nikolaus S., Albrecht M., Hampe J., Lucius R., Klöppel G., Eickhoff H., Lehrach H., Lengauer T., Schreiber S. (2005) Dissection of the inflammatory bowel disease transcriptome using genome-wide cDNA microarrays. PLoS Med. 2, e199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Arlt A., Schäfer H., Kalthoff H. (2012) The “N-factors” in pancreatic cancer: functional relevance of NF-κB, NFAT, and Nrf2 in pancreatic cancer. Oncogenesis 1, e35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Rushworth S. A., Zaitseva L., Murray M. Y., Shah N. M., Bowles K. M., MacEwan D. J. (2012) The high Nrf2 expression in human acute myeloid leukemia is driven by NF-κB and underlies its chemoresistance. Blood 120, 5188–5198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yu M., Li H., Liu Q., Liu F., Tang L., Li C., Yuan Y., Zhan Y., Xu W., Li W., Chen H., Ge C., Wang J., Yang X. (2011) Nuclear factor p65 interacts with Keap1 to repress the Nrf2-ARE pathway. Cell. Signal. 23, 883–892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kim J., Cha Y. N., Surh Y. J. (2010) A protective role of nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor-2 (Nrf2) in inflammatory disorders. Mutat. Res. 690, 12–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]