Background: Vesicle trafficking plays important roles in regulating cell adhesion and motility.

Results: Depletion of the membrane fusion protein, N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein α (αSNAP), induced cell detachment, whereas overexpression of this vesicle regulator increased cell-matrix adhesion.

Conclusion: αSNAP promotes cell-matrix adhesion by controlling integrin trafficking and assembly of focal adhesions.

Significance: The αSNAP level may serve as a molecular rheostat controlling matrix adhesion and cell motility under normal conditions and in diseases.

Keywords: Cell Adhesion, Cell Migration, Cell Motility, Snare Proteins, Trafficking

Abstract

Integrin-based adhesion to the extracellular matrix (ECM) plays critical roles in controlling differentiation, survival, and motility of epithelial cells. Cells attach to the ECM via dynamic structures called focal adhesions (FA). FA undergo constant remodeling mediated by vesicle trafficking and fusion. A soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor (NSF) attachment protein α (αSNAP) is an essential mediator of membrane fusion; however, its roles in regulating ECM adhesion and cell motility remain unexplored. In this study, we found that siRNA-mediated knockdown of αSNAP induced detachment of intestinal epithelial cells, whereas overexpression of αSNAP increased ECM adhesion and inhibited cell invasion. Loss of αSNAP impaired Golgi-dependent glycosylation and trafficking of β1 integrin and decreased phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and paxillin resulting in FA disassembly. These effects of αSNAP depletion on ECM adhesion were independent of apoptosis and NSF. In agreement with our previous reports that Golgi fragmentation mediates cellular effects of αSNAP knockdown, we found that either pharmacologic or genetic disruption of the Golgi recapitulated all the effects of αSNAP depletion on ECM adhesion. Furthermore, our data implicates β1 integrin, FAK, and paxillin in mediating the observed pro-adhesive effects of αSNAP. These results reveal novel roles for αSNAP in regulating ECM adhesion and motility of epithelial cells.

Introduction

Adhesion of epithelial cells to extracellular matrix (ECM)2 is a key determinant of tissue integrity and morphogenesis. It allows formation of simple planar epithelial sheets as well as complex three-dimensional tubules, ducts, and glands (1, 2). Adhesion to ECM is critical for a steady-state migration of epithelial cells in constantly self-renewing tissues such as intestinal mucosa (3, 4). It also drives disease-related cell motility during wound healing in inflamed mucosa or invasion of metastatic tumor cells (5, 6). Epithelial cells attach to ECM via specialized adhesion structures formed at their basal surface. Focal adhesions (FA) represent the most abundant and important type of ECM adhesions. FA-mediated adhesion is primarily dependent on integrins, a family of heterodimeric transmembrane receptors that are engaged in direct interactions with ECM components (7, 8). Integrins are activated, clustered, and linked to the underlying cytoskeleton by a number of cytoplasmic scaffolding molecules including paxillin, vinculin, and talin (9, 10). Additionally, FA are enriched in signaling molecules. Among these signaling molecules non-receptor kinases, such as members of the focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and Src families, are known to drive FA biogenesis by activating scaffolding proteins and stimulating actin polymerization at the ECM attachment sites (11, 12).

FA are very dynamic structures that undergo a constant remodeling. A simplified model of FA dynamics in motile cells implies that FA become assembled and disassembled at the migrating leading edge and the trailing end of the cell, respectively (13, 14). Molecular components of disassembled FA get delivered to the leading edge where they are reused during formation of new adhesion complexes. Such recycling of molecular constituents is important for the continuity of FA biogenesis and ECM adhesion. Vesicle trafficking is known to be a major mechanism of FA remodeling. It is required for endocytosis and recycling of FA proteins as well as for the delivery of newly synthesized FA components via exocytosis from the Golgi to the plasma membrane (15, 16). Generally, exocytosis and recycling represent complex processes involving hierarchically organized cascades of vesicle tethering, docking, and fusion with the plasma membrane (17, 18). Each step of this cascade is controlled by specific multiprotein machinery to ensure fidelity and efficiency of inter-membrane interactions. Membrane fusion is the final and rate-limiting step of this process resulting in either insertion of designated molecules into the plasma membrane or their release from the cells. Membrane fusion is mediated by the SNARE (soluble N-ethylmalemide-sensitive factor associated receptor) protein complex (19, 20). Direct interactions of different SNARE proteins located on the vesicle and the target membrane bring two lipid bilayers in close proximity, driving their fusion. A number of previous studies implicated several SNARE proteins in regulation of integrin trafficking, FA assembly, and cell-matrix adhesion. Cell adhesion and motility appear to be orchestrated by SNAREs located in different cellular compartments including plasma membrane-resident syntaxins 3 and 4 and SNAP23 (21, 22), endosomal vesicle-associated membrane proteins 3 (22–24), and Golgi/endosomal syntaxin 6 (24–26).

Membrane fusion yields extremely stable cis-SNARE complexes that must be disassembled and reused for new fusion events. Disassembly of these post-fusion SNARE complexes requires an oligomeric ATPase, N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor (NSF) and its adaptors, soluble NSF-attachment proteins (SNAPs) (27, 28). Ubiquitously expressed αSNAP and neuronal βSNAP are capable of interacting simultaneously with SNAREs and NSF via distinct binding sites (28–30). These interactions result in NSF recruitment to the SNARE complex, stimulation of its ATPase activity, and transduction of conformational changes from NSF leading to disassembly of the SNARE cylinder. Overexpression of a dominant-negative NSF mutant or introduction of NSF-inhibiting peptides was shown to interrupt integrin trafficking and diminish ECM adhesion and migration of epithelial cells and leukocytes (31–33). Because αSNAP is a critical regulator of NSF activity, with a number of NSF-independent cellular functions (34–37), it is essential to characterize its effects on ECM adhesion and cell motility. Surprisingly, this important question has not been previously addressed. In this study, we identified αSNAP as a critical positive regulator of ECM adhesion of human epithelial cells via multiple mechanisms that control FA assembly and Golgi-dependent maturation and trafficking of β1 integrin.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Antibodies and Other Reagents

The following primary polyclonal and monoclonal (mAb) antibodies were used to detect matrix adhesion, trafficking, and signaling proteins: anti-αSNAP, mAb (Abcam, Cambridge, MA); anti-β1 integrin mAb (Novus Biological, Littleton, CO); anti-α5 integrin, polyclonal antibody (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA); anti-NSF, total paxillin, GBF1, and p130cas mAbs (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA); anti-talin and vinculin mAbs (Sigma); anti-phospho-paxillin, β4-integrin, cleaved poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase, total FAK, phospho-FAK, and GAPDH polyclonal Abs (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA). For functional study β1 integrin inhibitory antibody (clone MAB13) and its rat isotype control NA/NL, both from BD Biosciences, were used. Alexa 488 or Alexa 555 dye-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit and goat anti-mouse secondary antibodies were obtained from Invitrogen. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit and anti-mouse secondary antibodies were purchased from Bio-Rad. Swainsonine, 1-deoxymannojirimycin (DMJ), and PF-431396 were purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, UK), whereas peptide N-glycosidase F was from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA). All other reagents were obtained from Sigma.

Cell Culture

SK-CO15 (a gift from Dr. E. Rodriguez-Boulan, Weill Medical College of Cornell University, NY) human colonic epithelial cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented by 10% fetal bovine serum as previously described (38, 39). Cells were grown in standard T75 flasks and, for immunolabeling/confocal microscopy experiments, were seeded on either collagen-coated, permeable polycarbonate filters 0.4-μm pore size (Costar, Cambridge, MA) or collagen-coated coverslips. For biochemical experiments, the cells were seeded on 6-well plastic plates.

RNA Interference

Small interfering (si) RNA-mediated knockdown of αSNAP, NSF, GBF1, β1, and β4 integrins was carried out as previously described (35, 40, 42). Individual siRNA duplexes, GAAGGUGGCUGGUUACGCU (duplex 1) and CAGAGUUGGUGGACAUCGA (duplex 2; Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO), were used to down-regulate αSNAP expression, whereas knockdown of other targets was performed by using gene-specific siRNA pools purchased either from Dharmacon or Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX). A noncoding siRNA duplex-2 (Dharmacon) served as a control. SK-CO15 cells were transfected using DharmaFect1 in Opti-MEM I medium (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol with a final siRNA concentration of 50 nm. Cells were harvested and analyzed 3–4 days after transfection.

Preparation of αSNAP-overexpressing Epithelial Cells

For rescue experiments, the coding sequence of bovine αSNAP (gift from Dr. Reinhard Jahn, Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry, Gottingen, Germany) was cloned in pLXSN retroviral vector (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) as a BamHI-EcoRI fragment. The bovine αSNAP transcript has 4 nucleotide mismatches in the corresponding sequences and is not targeted by siRNA duplexes 1 and 2; the duplexes used to deplete human αSNAP. For retroviral particle production, ProPak-A cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were transfected with either empty control vector or bovine αSNAP-containing vector using a Trans-IT 293 transfection reagent (MirusBio, Madison, WI). To harvest the viruses, infected cells grown to 75% confluence were incubated for 16 h at 37 °C. Collected media was passed through a 0.45-μm syringe filter and stored at −80 °C. SK-CO15 cells plated at 30–40% confluence were exposed overnight to viruses preincubated with 4 μg/ml of Polybrene. Stable cell lines expressing either bovine αSNAP or their appropriate controls were selected with 1.2 μg/ml of G418. For expression of wild-type (wt) αSNAP, its coding sequence was excised (BamHI and EcoRI, blunted by Klenow) and inserted into lentivector pWPT-GFP (obtained from Addgene, Boston, MA) at the BamHI site, which was also blunted by Klenow DNA polymerase. The site-directed mutagenesis of M105I and L294A was carried out using QuikChange Site-directed Mutagenesis Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). To produce lentiviral supernatants, HEK293LT cells (6-cm dish) were co-transfected with 5 μg of lentiplasmids, 4 μg of psPAX2, and 1 μg of pCMV-VSV-G plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000. Virus-containing supernatants were collected and combined from 36 to 60 h post-transfection and used to infect cells in the presence of 8 μg/ml of Polybrene (Sigma).

Immunofluorescence Labeling and Image Analysis

Epithelial cell monolayers were fixed/permeabilized in 100% methanol for 20 min at −20 °C. Fixed cells were blocked in HEPES-buffered Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS+) containing 1% bovine serum albumin (blocking buffer) for 60 min at room temperature and incubated for another 60 min with primary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer. Cells were then washed, incubated for 60 min with Alexa dye-conjugated secondary antibodies, rinsed with blocking buffer, and mounted on slides with ProLong Antifade medium (Invitrogen). Immunofluorescence labeled cell monolayers were examined with an Olympus FluoView 1000 confocal microscope (Olympus America, Center Valley, PA). The Alexa Fluor 488 and 568 signals were imaged sequentially in frame-interlace mode to eliminate cross-talk between channels. The images were processed using the Olympus FV10-ASW 2.0 Viewer software and Adobe Photoshop. Images shown are representative of at least 3 experiments, with multiple images taken per slide.

Cell Adhesion and Matrigel Invasion Assays

Cell adhesion assay was performed as previously described (43). Briefly, 24-well plates were coated with collagen I and washed with sterile PBS. Control and αSNAP overexpressing cells were trypsinized, harvested, counted with a hemocytometer, and resuspended in DMEM. Where indicated, cells were preincubated with either isotype control or MAB13 antibodies (5 μg/ml) for 2 h (44). 1 × 104 cells were added to each well and cells were allowed to adhere to the ECM for 30 min at 37 °C. After incubation, unattached cells were removed and attached cells were fixed and labeled using a DIFF stain kit (IMEB Inc., San Marcos, CA). Adherent cells were photographed under bright field microscope.

The invasion assay was performed using commercially available BD Biocoat invasion chambers (BD Biosciences). Cells were trypsinized, resuspended in DMEM without serum, and added to the upper chamber at a concentration of 5 × 104 cells per chamber. In the lower chamber complete growth medium containing 10% FBS as a chemoattractant was added and cells were allowed to migrate for 24 h at 37 °C. Cells were fixed and stained using the same DIFF stain kit described above and non-migrated cells were removed from the top of the membranes using cotton swabs. For both adhesion and invasion experiments, the number of cells was determined by manual counting in 15 randomly selected microscopic images obtained from 3 independent experiments.

Immunoblotting

Cells were homogenized in RIPA lysis buffer (20 mm Tris, 50 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, 2 mm EGTA, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Triton X-100, and 0.1% SDS, pH 7.4), containing a protease inhibitor mixture (1:100, Sigma) and phosphatase inhibitor mixtures 1 and 2 (both at 1:200, Sigma). Lysates were cleared by centrifugation (20 min at 14,000 × g), diluted with 2× SDS sample buffer, and boiled. SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting were conducted by standard protocols with an equal amount of total protein (10 or 20 μg) per lane. Protein expression was quantified by densitometry of three immunoblot images, each representing an independent experiment, with an Epson Perfection V500 photoscanner and ImageJ version 1.47 software (National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD). Data were presented as normalized values assuming the expression levels in control siRNA-treated groups were at 100%. Statistical analysis was performed with row densitometric data using Microsoft Excel.

Real-time RT-PCR

RNA was isolated using an RNeasy mini kit and treated with DNase I prior to cDNA synthesis using an iSCRIPT cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). iTaq Universal SYBR Green supermix was used to perform real-time PCR on an Applied Biosystems ABI 9700HT REAL TIME PCR SYSTEM, using the following primers for human FAK: forward, GCCTTATGACGAAATGCTGGGC and reverse, CCTGTCTTCTGGACTCCATCCT. Cycle threshold values (Ct) were used to calculate the fold-change in target mRNA using the ΔΔCt method. The 18 S ribosomal RNA subunit was used as a reference gene.

Statistics

For Western blot quantification numerical values from individual experiments were pooled and expressed as mean ± S.E. throughout. Obtained numbers were compared by two-tailed Student's t test, with statistical significance assumed at p < 0.05. Invasion and migration data were analyzed using Sigma-PLOT professional statistics software (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA). For analyses of variance, one-way analysis of variance with pairwise multiple tests was used for intergroup comparisons with p < 0.001.

RESULTS

Loss of αSNAP Expression Impairs ECM Adhesion of Human Epithelial Cells

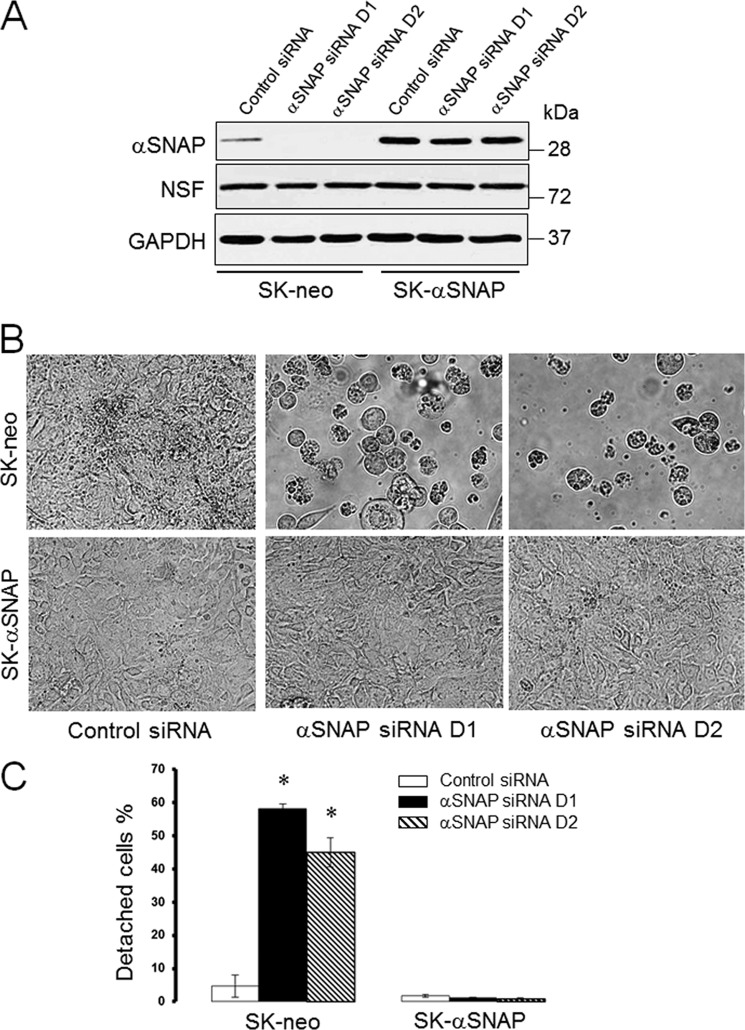

During our previous studies we made a serendipitous observation that loss of αSNAP expression caused a marked detachment of cultured human epithelial cells. Because this observation suggested a previously unrecognized role of αSNAP in regulating ECM adhesion, we decided to investigate molecular mechanisms that may determine poor adhesiveness of αSNAP-depleted epithelia. RNA interference (RNAi) was used to down-regulate αSNAP expression in SK-CO15 human intestinal epithelial cells along with a rescue approach involving overexpression of RNAi-resistant bovine αSNAP. Transfection with two different siRNA duplexes dramatically reduced the αSNAP protein level in control SK-CO15 human colonic epithelial cells (SK-neo) without affecting expression of this protein in bovine αSNAP-rescued cells (SK-αSNAP; Fig. 1A). Consistent with our previous results (34), NSF expression was not modulated by the αSNAP level (Fig. 1A). Remarkably, depletion of αSNAP resulted in a substantial (up to 60%) detachment of SK-CO15 cells on day 3 post-transfection (Fig. 1, B and C). Overexpression of bovine αSNAP prevented this cell detachment, indicating that the observed defects of ECM adhesion represent a specific consequence of decreased αSNAP expression. Beside SK-CO15 cells, loss of αSNAP decreased adhesiveness of HeLa, HEK-293, PC3, and HCT116 cells (data not shown), highlighting a generality of this response in different types of cultured epithelial cells.

FIGURE 1.

Loss of αSNAP triggers detachment of human intestinal epithelial cells. Control SK-CO15 cells (SK-neo) and cells stably expressing siRNA-resistant bovine αSNAP (SK-αSNAP) were transfected with either control or two human αSNAP-specific siRNA duplexes (D1 and D2). A, expression of αSNAP and its binding partner NSF was determined 72 h post-transfection. B and C, cell detachment was examined by counting adhered and total number of cells using bright field microscopy 72 h post-transfection. Data are presented as the mean ± S.E. (n = 3); *, p < 0.001 compared with control siRNA-transfected cells.

Loss of αSNAP Disrupts Morphology of FA and Alters Processing of Their Major Molecular Constituents

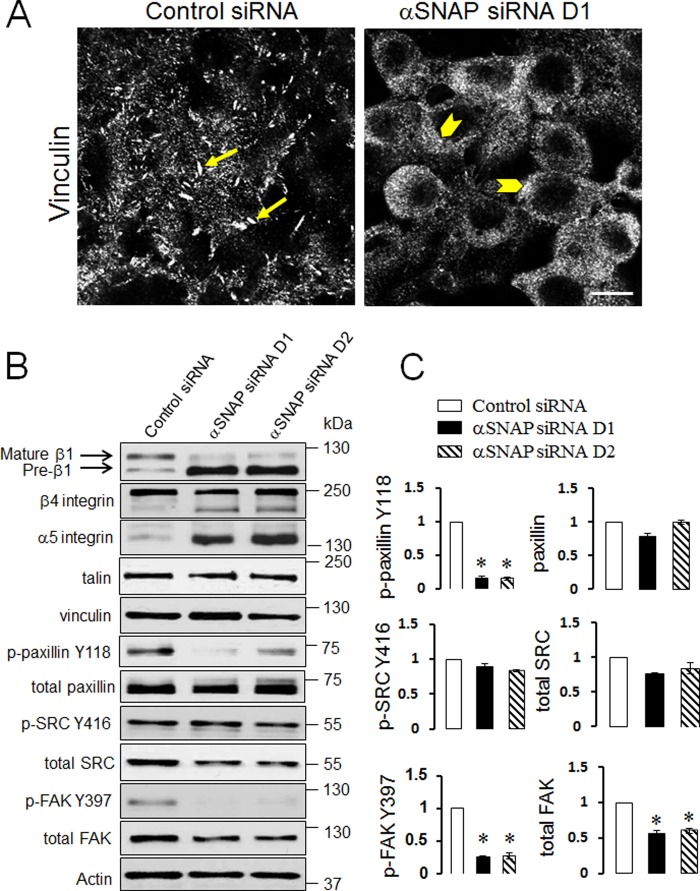

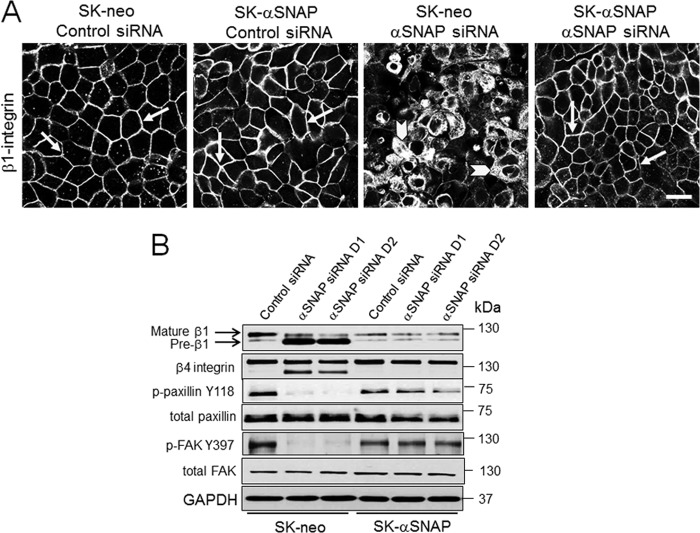

Because FA are known to be the major structural determinants of epithelial cell attachment to ECM, we hypothesized that poor adhesiveness of αSNAP-depleted cells can be due to impaired FA assembly. To test this hypothesis, FA were visualized in control and αSNAP-depleted SK-CO15 cells by using immunolabeling of vinculin with subsequent confocal microscopy. In control cells, a significant fraction of vinculin accumulated within large elongated basal clusters representing FA (Fig. 2A, arrows). By contrast, no defined FA was detected in αSNAP-depleted cells where vinculin staining was diffusely distributed within the cytoplasm and cell membrane (Fig. 2A, arrowheads). Immunoblotting analysis of major transmembrane, scaffolding, and signaling constituents of FA revealed two prominent effects of αSNAP depletion on molecular organization of FA. The first effect was a marked decrease in phosphorylation of paxillin and FAK accompanied by a significant expressional down-regulation of FAK (Fig. 2, B and C). The magnitude of FAK dephosphorylation (∼4-fold) was higher than the magnitude of total FAK down-regulation (∼2-fold). This difference indicates multiple mechanisms of FAK inactivation by αSNAP knockdown. Although the mechanism of reduced total FAK expression remains to be elucidated, our quantitative RT-PCR analysis ruled out decreased mRNA transcription (data not shown). The second effect of αSNAP depletion was noticeable defects in integrin maturation. Indeed, immunoblotting analysis of control SK-CO15 cells detected a major β1 integrin doublet (Fig. 2B) composed of a predominant slowly migrating mature protein and a faster migrating β1 integrin precursor (45). Remarkably, loss of αSNAP resulted in accumulation of β1 integrin precursor as manifested by a dramatic increase in the intensity of the lower band in the doublet (Fig. 2B). Likewise, αSNAP-depleted cells demonstrated significant accumulation of slowly migrating immature forms of β4 and α5 integrins (Fig. 2B). Immunofluorescence analysis of control SK-CO15 cells demonstrated predominant localization of β1 integrin on the lateral plasma membrane in the areas of cell-cell contacts (Fig. 3A, arrows). By contrast, loss of αSNAP resulted in diffuse intracellular distribution of β1 integrin (Fig. 3A, arrowheads). Interestingly, overexpression of siRNA-resistant bovine protein completely restored normal plasma membrane localization of β1 integrin and rescued defects of integrin maturation and phosphorylation of FA proteins in αSNAP-depleted SK-CO15 cells (Fig. 3, A and B). Together these results indicate that loss of αSNAP impairs maturation and plasma membrane delivery of integrins and interrupts signaling events essential for FA assembly.

FIGURE 2.

Loss of αSNAP disrupts structure of focal adhesions and affects expression and processing of key FA proteins. Control and αSNAP siRNA-transfected SK-CO15 cells were fixed 72 h post-transfection and FA were visualized by immunofluorescence labeling of vinculin and confocal microscopy (A). Arrows show intact vinculin-based FA structures in control cells, whereas arrowheads indicate diffuse vinculin labeling in αSNAP-depleted cells. Scale bar, 20 μm. Expression and phosphorylation of major transmembrane, scaffolding, and signaling FA proteins in control and αSNAP-depleted epithelial cells was determined by immunoblotting analysis (B) with densitometric quantification (C). Data are presented as the mean ± S.E. (n = 3); *, p < 0.001 compared with control siRNA-transfected cells.

FIGURE 3.

The effects of αSNAP depletion on β1 integrin and other FA proteins can be rescued by expression of siRNA-resistant αSNAP. SK-CO15 cells stably expressing siRNA-resistant bovine αSNAP (SK-αSNAP) and their empty vector controls (SK-neo) were transfected with either control or αSNAP-specific siRNAs. A, localization of β1 integrin was determined by immunofluorescence labeling and confocal microscopy 72 h post-transfection. B, expression and processing of different FA proteins was determined by immunoblotting. Arrows indicate plasma membrane labeling of β1 integrin in control or αSNAP-siRNA-transfected and rescued cells. Arrowheads show intracellular localization of β1 integrin in αSNAP-depleted cells without rescue. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Loss of ECM Adhesion in αSNAP-depleted Cells Is Independent of Apoptosis

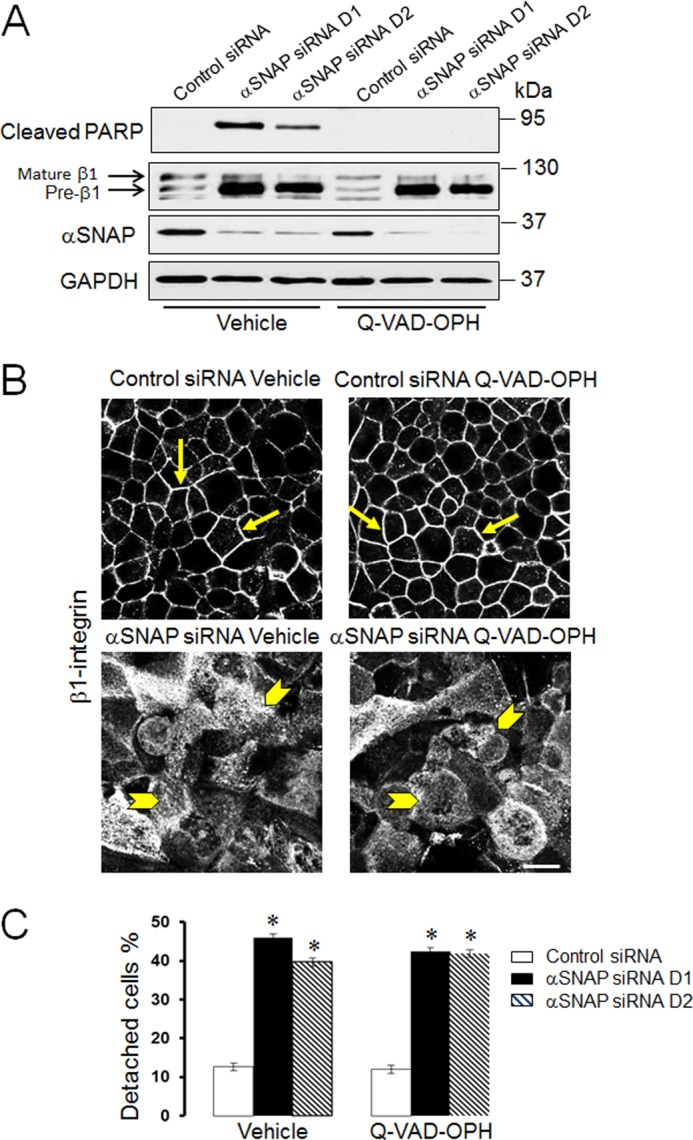

Recent studies by our group (35) and others (46) have found that down-regulation of αSNAP expression promotes epithelial cell apoptosis. One can therefore suggest that the observed loss of ECM adhesion in αSNAP-depleted cells represents a simple consequence of apoptotic cell death. To investigate this possibility, control and αSNAP siRNA-transfected SK-CO15 cells were treated with either vehicle or a pan-caspase inhibitor, Q-VAD-OPH (20 μm). Caspase inhibition effectively prevented apoptosis in αSNAP-depleted cells as indicated by a complete suppression of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase cleavage (Fig. 4A) and lack of caspase 3 activation (data not shown). However, inhibition of apoptosis did not alleviate abnormal maturation and mislocalization of β1 integrin caused by αSNAP knockdown (Fig. 4, A and B, arrowheads) and failed to prevent cell detachment (Fig. 4C).

FIGURE 4.

Effect of αSNAP depletion on ECM adhesion and integrin processing are independent from induction of apoptosis. SK-CO15 cells were transfected with either control or two αSNAP-specific siRNA duplexes. 24 h later these cells were treated for an additional 48 h with either vehicle or a pan-caspase inhibitor, Q-VAD-OPH. Cells were examined for apoptosis induction and β1 integrin maturation (A), β1 integrin localization (B), and cell attachment to ECM (C). Arrows indicate plasma membrane labeling of β1 integrin in control SK-CO15 cells, whereas arrowheads show intracellular localization of β1 integrin in αSNAP-depleted cells treated and untreated with pan-caspase inhibitor. Data are presented as the mean ± S.E. (n = 3); *, p < 0.001 compared with control siRNA-transfected cells. Scale bar, 20 μm.

αSNAP Modulates Epithelial ECM Adhesion and Motility by NSF-independent Mechanisms

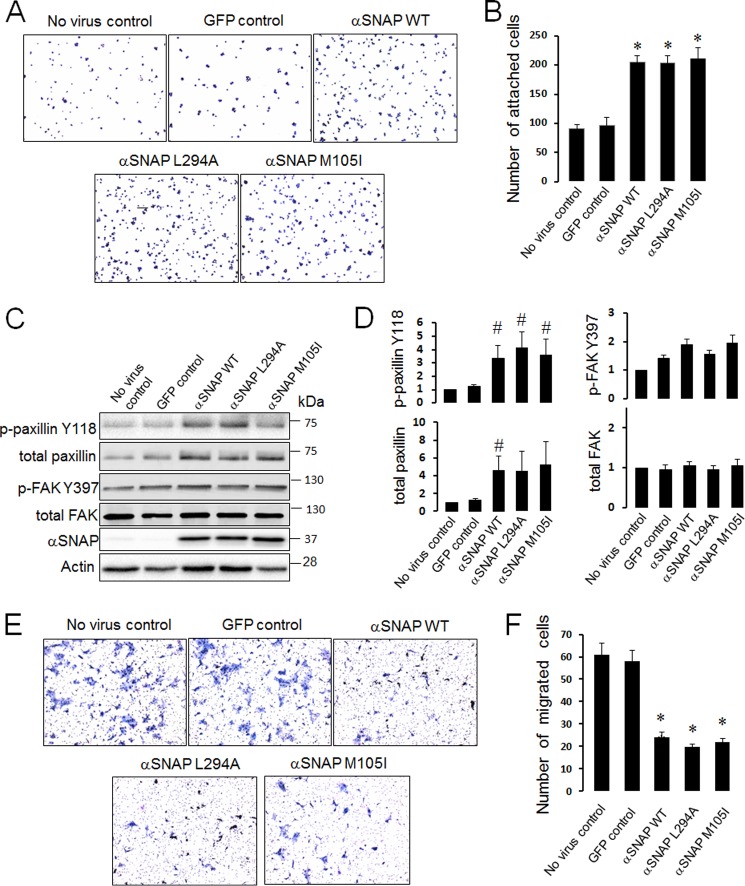

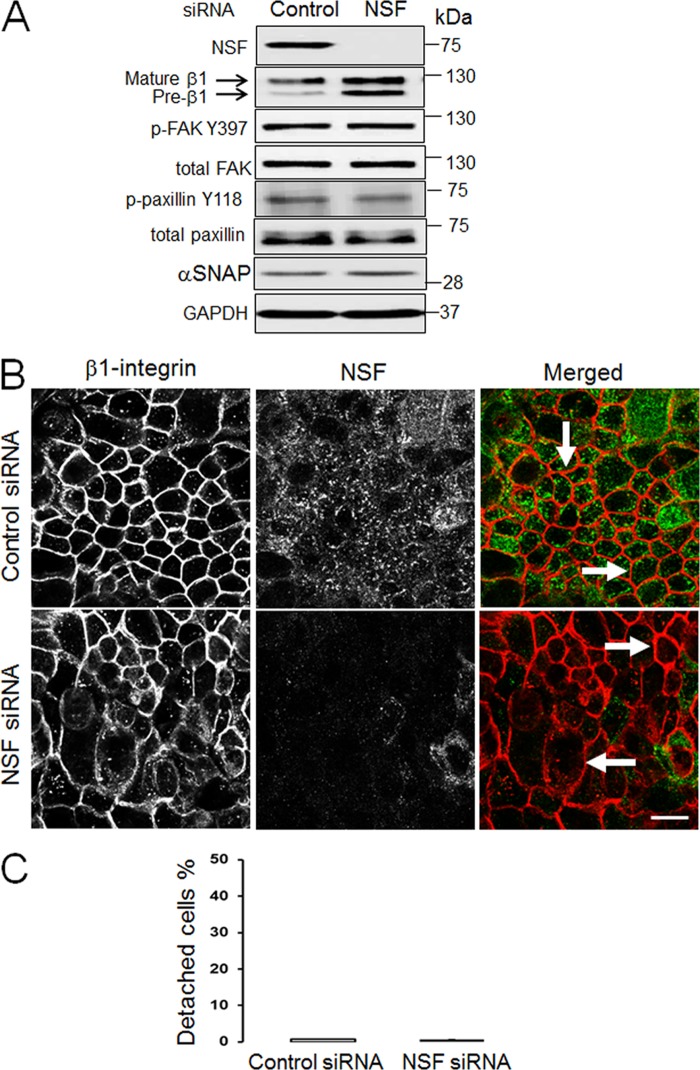

Because αSNAP depletion dramatically decreased ECM adhesion of epithelial cells, it is important to examine whether increased expression of this vesicle fusion regulator may have pro-adhesive effects. This question was addressed by expressing either wild-type αSNAP or its two known mutants in SK-CO15 cells using a lentiviral delivery system. The L294A mutant is unable to activate NSF and therefore has dominant-negative effects on SNARE-mediated exocytosis (47), whereas the M105I (hyh) mutant has increased affinity to another αSNAP target, AMP-activated protein kinase (37). SK-CO15 cells overexpressing wild-type αSNAP demonstrated an ∼2-fold increase in adhesion to collagen I compared with non-transfected or control GFP-transfected cells (Fig. 5, A and B). Both L294A and M105I mutants accelerated ECM adhesion similarly to wild-type αSNAP (Fig. 5, A and B). Interestingly, all overexpressed αSNAP proteins significantly increased levels of total and phosphorylated paxillin (Fig. 5, C and D). Such increased ECM adhesion of αSNAP-overexpressing cells was accompanied by ∼3-fold reduction of their invasion in Matrigel (Fig. 5, E and F). It is noteworthy that anti-invasive effects of αSNAP mutants were similar to that of the wild-type protein (Fig. 5, E and F). We also investigated effects of αSNAP knockdown on epithelial cell motility and observed a complete block of Matrigel invasion in αSNAP-depleted SK-CO15 cells (data not shown). Similar effects of wild-type and L294A αSNAP on epithelial cell adhesion and migration suggest that these αSNAP activities may not depend on its major binding partner, NSF. To obtain more evidence supporting this hypothesis we examined whether depletion of NSF results in defects of epithelial cell adhesiveness recapitulating those of αSNAP knockdown. In concordance with our previous studies (34, 35), NSF-specific siRNA markedly down-regulated expression of the targeted protein in SK-CO15 cells without decreasing the αSNAP level (Fig. 6A). Moreover, such NSF depletion did not result in significant dephosphorylation of paxillin and FAK (Fig. 6A), Interestingly, NSF depletion increased the relative amount of immature β1 integrin (Fig. 6A) and enhanced integrin accumulation within intracellular vesicles (Fig. 6B). However, in contrast to αSNAP knockdown, the majority of β1 integrin was able to reach the plasma membrane in NSF-depleted cells (Fig. 6B, arrows). Furthermore, loss of NSF failed to induce SK-CO15 cell detachment (Fig. 6C) thereby indicating a lack of dramatic effect on ECM adhesion. Collectively, our data suggests that disruption of NSF-mediated vesicle fusion cannot be a major mechanism of impaired FA assembly and defective ECM adhesion in αSNAP-depleted epithelial cells.

FIGURE 5.

Overexpression of αSNAP increases ECM adhesion and inhibits epithelial cell invasion. SK-CO15 cells were transduced with lentiviruses bearing control GFP, wild-type αSNAP, or one of two αSNAP mutants (L294A and M105I). Cells were harvested 48 h post-transduction and their adhesion to collagen I (A and B) expression of FA proteins (C and D) and invasion into Matrigel (E and F) was examined as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Data are presented as the mean ± S.E. (n = 3); *, p < 0.001; #, p < 0.05 compared with GFP control virus-treated cells.

FIGURE 6.

Effects of NSF knockdown on FA proteins and ECM adhesion in intestinal epithelial cells. SK-CO15 cells were transfected with either control or NSF siRNAs. 72 h post-transfection cells were analyzed for expression of NSF, αSNAP, and different FA proteins (A), β1 integrin localization (B), and ECM attachment (C). Localization of β1 integrin in control and NSF-depleted cell monolayers was determined by dual immunolabeling of β1 integrin (red) and NSF (green). Arrows show plasma membrane localization of β1 integrin in control and NSF-depleted cells. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Disruption of the Golgi Recapitulates the Effects of αSNAP Knockdown on ECM Adhesion and Processing of FA Proteins

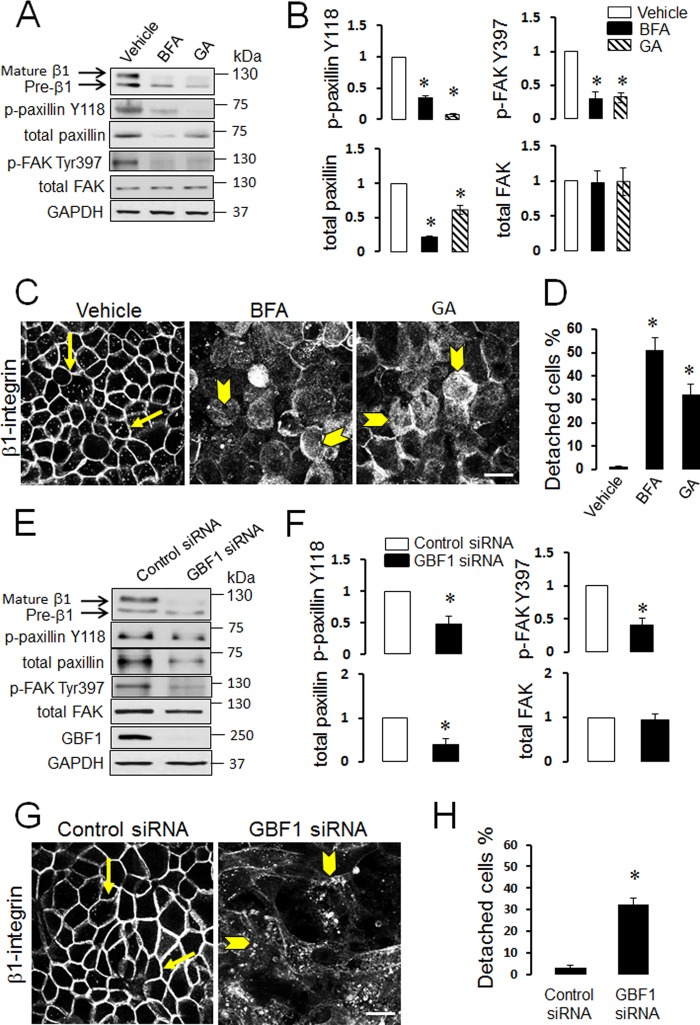

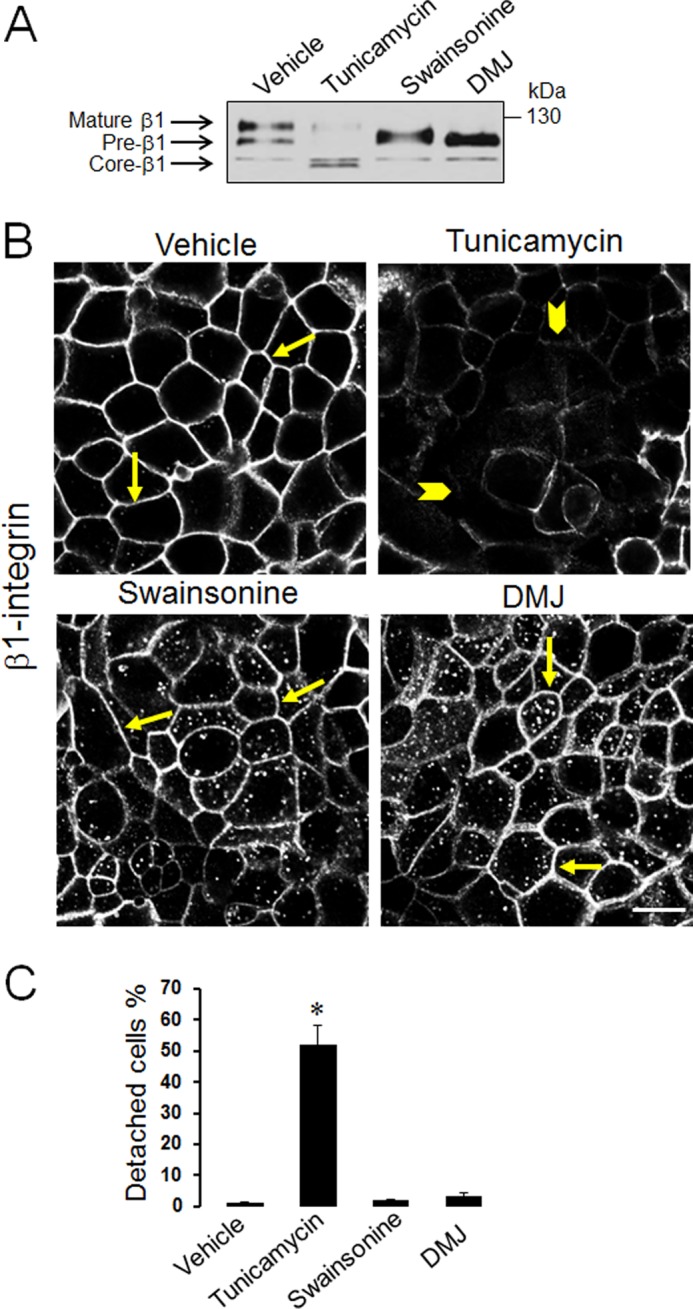

Our recent studies documented dramatic fragmentation of the Golgi complex in αSNAP-depleted epithelial cells and demonstrated that Golgi disruption phenocopied many cellular effects of αSNAP knockdown (34–36). Therefore it was next asked if Golgi abnormalities may also mediate diminished ECM adhesion caused by αSNAP depletion. Effect of Golgi fragmentation on SK-CO15 cell adhesion was investigated by using two known pharmacological Golgi disruptors, brefeldin A and Golgicide A (48, 49). In agreement with our previously published results (35), both agents induced complete dispersion of the compact Golgi morphology visualized by either Giantin or GM130 immunolabeling (data not shown). Furthermore, 24 h treatment of SK-CO15 with either brefeldin A (1 μm) or Golgicide A (50 μm) caused a number of biochemical and phenotypic abnormalities including decreased expression and dephosphorylation of paxillin and FAK (Fig. 7, A and B), inhibition of β1 integrin maturation and trafficking (Fig. 7, A and C), and significant (up to 50%) cell detachment (Fig. 7D). All these alterations recapitulated the adhesion defects of αSNAP-depleted cells. Brefeldin A and Golgicide A are known to have one common molecular target, Golgi brefeldin factor 1 (GBF1), which serves as guanine nucleotide exchange factors for Golgi-resident ARF small GTPases (49–51). Previously, we demonstrated that loss of αSNAP decreased GBF1 expression in SK-CO15 cells and that GBF1 knockdown mimicked major effects of αSNAP depletion on epithelial junctions and the autophagic flux (34, 36). Therefore, we sought to investigate if loss of GBF1 can recapitulate disruption of ECM adhesion observed in αSNAP knockdown. Expression of GBF1 was dramatically down-regulated in SK-CO15 cells by RNAi (Fig. 7E) resulting in decreased levels of total and phosphorylated paxillin and dephosphorylation of FAK (Fig. 7, E and F). This was accompanied by defects of β1 integrin maturation (Fig. 7E), dramatic accumulation of β1 integrin within cytoplasmic vesicles (Fig. 7G, arrowheads), and significant (∼30%) cell detachment (Fig. 7H). All these changes closely resembled the defects in ECM adhesion observed in αSNAP-depleted epithelial cells. Because altered maturation of β1 integrin appeared to be a prominent consequence of αSNAP knockdown linked to Golgi fragmentation, we sought to investigate mechanisms underlying such integrin misprocessing. It is generally believed that the major β1 integrin doublet detected by immunoblotting reflects different glycosylated states of the protein with the upper (∼125 kDa) and lower (∼105 kDa) bands representing a fully glycosylated and incompletely glycosylated protein, respectively (45). Post-translational modification of β integrin chains is a two-step process that involves initial N-glycosylation in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and further glycosylation by Golgi-resident enzymes (52, 53). Because structure and function of the Golgi and the ER are interdependent, Golgi fragmentation in αSNAP-depleted cells may impair activity of glycosylation enzymes residing in both organelles. Consequently, we next sought to determine which step of β1 integrin glycosylation is impaired in αSNAP-depleted epithelial cells. Control SK-CO15 cells were treated with either a known inhibitor of ER-dependent N-glycosylation, tunicamycin (54), or inhibitors of Golgi-dependent glycosylation, DMJ and swainsonine (52, 55). Tunicamycin (1 μm) eliminated a typical β1 integrin doublet and resulted in accumulation of much faster migrating integrin bands at ∼85 kDa (Fig. 8A) that corresponds to a core non-glycosylated β1 integrin polypeptide (45). Similar transformation of the β1 integrin doublet into the non-glycosylated core species was detected after treatment of control and αSNAP-depleted cell lysates with peptide N-glycosidase F removing all saccharide moieties (data not shown). Because the β1 integrin band at 125 kDa accumulated in the αSNAP-depleted epithelial cell was clearly distinct from the deglycosylated core protein, we concluded that αSNAP depletion did not affect initial N-glycosylation of β1 integrin at the ER. By contrast, inhibition of Golgi-dependent glycosylation by either swainsonine (50 μm) or DMJ (50 μm) resulted in a disappearance of mature β1 integrin and accumulation of its immature form similar to that observed in αSNAP-depleted cells (Fig. 8A). This suggests that loss of αSNAP impairs glycosylation of β1 integrin in the Golgi. Interestingly, only inhibition of ER-dependent N-glycosylation by tunicamycin dramatically attenuated expression and plasma membrane delivery of β1 integrin, and impaired ECM adhesion of SK-CO15 cells (Fig. 8, B and C). By contrast, swainsonine and DMJ treatment increased the amount of intracellular β1 integrin, but did not completely block its accumulation at the plasma membrane (Fig. 8B). Furthermore, inhibition of Golgi glycosylation had no effects on cell attachment to ECM (Fig. 8C). This data suggests that although loss of αSNAP impaired β1 integrin glycosylation in the Golgi, we observed that the defect of β1 integrin maturation may not be sufficient to diminish ECM adhesion of αSNAP-depleted epithelial cells.

FIGURE 7.

Pharmacological or genetic disruption of the Golgi impairs expression/processing of FA proteins and weakens ECM adhesion of intestinal epithelial cells. A–D, SK-CO15 cells were incubated for 24 h with either vehicle, or one of two pharmacological Golgi disruptors, brefeldin A (BFA; 1 μm) and Golgicide A (GA; 50 μm). Cells were analyzed for FA protein expression (A and B), intracellular localization of β1 integrin (C) and ECM attachment (D). Data are presented as the mean ± S.E. (n = 3); *, p < 0.001 compared with vehicle-treated cells. E–H, cells were transfected with either control, or GBF1 siRNAs and their ECM attachment and adhesion protein expression and localization were examined 72 h post-transfection. Arrows indicate plasma membrane labeling of β1 integrin in control SK-CO15 cells, whereas arrowheads show intracellular localization of β1 integrin in Golgi-disrupted cells. *, p < 0.001 compared with control siRNA-transfected cells. Scale bar, 20 μm.

FIGURE 8.

Inhibitors of ER and Golgi-dependent glycosylation have distinct effects on β1 integrin processing and epithelial ECM adhesion. SK-CO15 cells were incubated for 24 h with either vehicle, a selective inhibitor of ER-dependent protein glycosylation, tunicamycin (1 μm), or an inhibitor of Golgi-dependent glycosylation, swainsonine (50 μm) and DMJ (50 μm). Cells were analyzed for β1 integrin processing (A) and localization (B) as well for ECM attachment (C). Arrows indicate normal localization of β1 integrin at the plasma membrane of vehicle, swainsonine, and DMJ-treated cells, whereas arrowheads point of decreased membrane accumulation of integrin following tunicamycin exposure. Data are presented as the mean ± S.E. (n = 3); *, p < 0.001 compared with vehicle-treated cells. Scale bar, 20 μm.

β1 Integrin and FA Proteins Mediate αSNAP-dependent Regulation of ECM Adhesion and Invasion

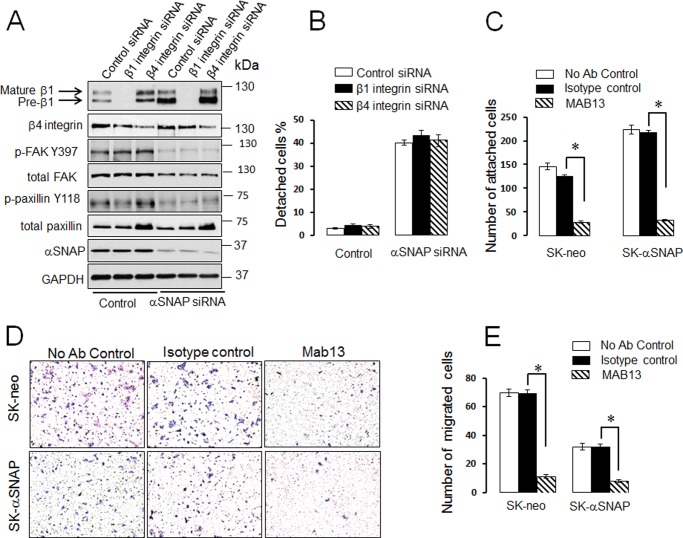

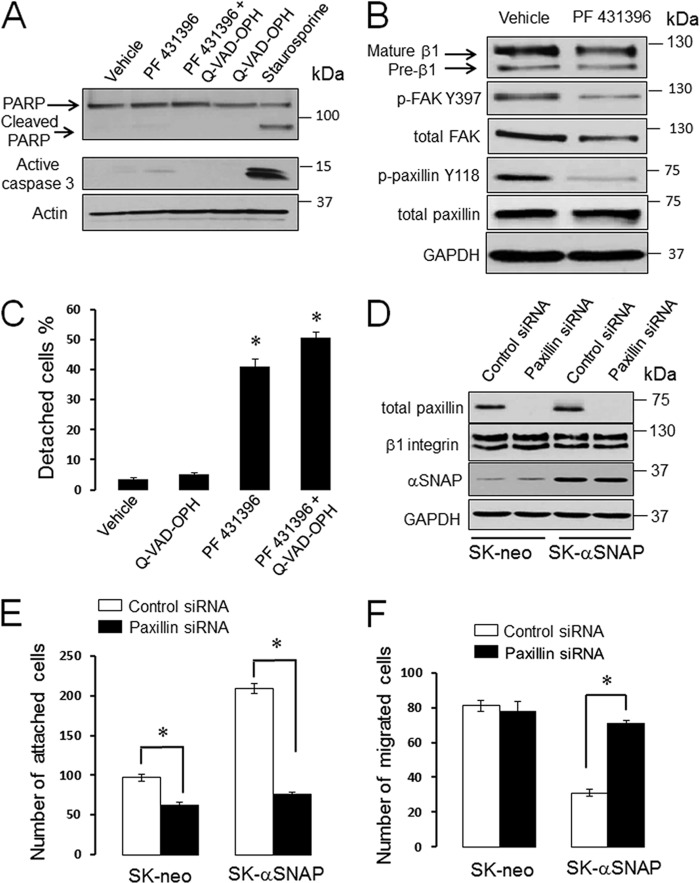

Because experiments with glycosylation inhibitors demonstrated that impaired β1 integrin maturation is not sufficient to explain the poor adhesiveness of αSNAP-depleted epithelial cells, we next sought to continue investigating the roles integrins play in our experimental conditions. Specifically, we asked two questions: (i) does inhibition of β1 or β4 integrin subunits recapitulate the effects of αSNAP knockdown on ECM adhesion and cell motility, and (ii) is accumulation of integrin precursors responsible for the loss of adhesiveness of αSNAP-depleted cells? Using RNAi, we down-regulated expression of β1 and β4 integrins either individually or in combination with αSNAP knockdown. Depletion of either β1 or β4 integrin in control SK-CO15 cells neither significantly altered phosphorylation of paxillin or FAK (Fig. 9A) nor induced spontaneous epithelial cell detachment (Fig. 9B). Likewise, co-knockdown of either β1 or β4 integrins with αSNAP failed to inhibit cell detachment (Fig. 9B). This finding argues against the roles of integrin precursors in these events. Interestingly, the matrix adhesion and Matrigel invasion assays showed that depletion of β1 integrin did not affect ECM attachment and invasion of control or αSNAP-overexpressing SK-CO15 cells (data now shown). These surprising results indicate that epithelial cells can compensate for the loss of individual integrin subunits. To avoid such compensation, we acutely blocked β1 integrin function by using the inhibitory MAB13 antibody (56). Compared with the isotope-specific control, MAB13 markedly inhibited ECM attachment and Matrigel invasion of control SK-CO15 cells (Fig. 9, C–E). Interestingly, the β1 integrin-inhibitory antibody reversed the hyper-adhesiveness of αSNAP-overexpressing SK-CO15 cells in parallel to reduced cell invasiveness (Fig. 9, C–E). Finally, we investigated if FAK and paxillin play roles in αSNAP-dependent regulation of ECM adhesion. SK-CO15 cells were exposed for 24 h to PF 431396 (20 μm), a dual pharmacological inhibitor of FAK, and its homolog, PYK2 (57). This treatment did not induce cell apoptosis as indicated by negligible poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase cleavage and caspase 3 activation (Fig. 10A), and resulted in a noticeable dephosphorylation of FAK and paxillin (Fig. 10B). It is of note that FAK inhibition triggered significant detachment of SK-CO15 cells that was not blocked by caspase inhibition (Fig. 10C). To examine the role of paxillin, we down-regulated its expression in control and αSNAP-overexpressing SK-CO15 cells. Remarkably, paxillin knockdown completely reversed the increased ECM adhesion and accelerated invasion of αSNAP-overexpressing cells without affecting motility of control cells (Fig. 10, E and F). Together, this data reveals multiple mechanisms underlying the effects of αSNAP on epithelial EMC adhesion that involve activity of β1 integrin, FAK family kinases, and the FA scaffolding protein, paxillin.

FIGURE 9.

Inhibitory anti-β1 integrin antibody, but not siRNA-mediated integrin depletion, inhibits epithelial ECM adhesion and invasion. A and B, SK-CO15 cells were transfected with control, β1 integrin, β4 integrin siRNAs, or co-transfected with siRNAs against these integrins and αSNAP. Expression of adhesion proteins and cell attachment to the substrate were examined 72 h post-transfection. C–E, control (SK-neo) and αSNAP-overexpressing (SK-αSNAP) epithelial cells were preincubated with either β1 integrin-inhibitory antibody, MAB13, or the isotype-matched control antibody. Cell adhesion to collagen I (C) and invasion into Matrigel (D and E) was examined as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Data are presented as the mean ± S.E. (n = 3); *, p < 0.001 compared with the isotype control antibody-treated cells.

FIGURE 10.

Inhibition of FAK and knockdown of paxillin affect epithelial ECM adhesion. A–C, SK-CO15 cells were incubated for 24 h with either vehicle, a pharmacological inhibitor of FAK activity, PF 431396 (20 μm), a caspase inhibitor Q-VAD-OPH, or their combination with subsequent analysis of cell apoptosis (A), FA protein expression (B), and cell attachment to the substrate (C). Data are presented as the mean ± S.E.(n = 3); *, p < 0.001 compared with vehicle-treated cells. D–F, control (SK-neo) and αSNAP-overexpressing (SK-αSNAP) epithelial cells were transfected with either control or paxillin siRNA and their adhesion protein expression (D) attachment to collagen I (E) and invasion into Matrigel (F) were examined 72 h post-transfection. *, p < 0.00 when compared with the appropriate control siRNA-treated groups.

DISCUSSION

ECM adhesion and motility of epithelial cells are regulated by elaborate vesicle trafficking/fusion machinery that is critical for assembly and remodeling of matrix adhesion complexes (58–60). The present study identifies novel functions of a key membrane fusion protein, αSNAP, in controlling ECM adhesion and invasion of human intestinal epithelial cells. Our results highlight αSNAP as an important positive regulator of ECM adhesion, because depletion of this protein leads to a marked cell detachment (Fig. 1B), whereas its overexpression dramatically enhances cell adhesiveness (Fig. 5). Although we provide the first direct evidence implicating αSNAP in regulating ECM adhesion, our findings are consistent with reported phenotypic consequences of decreased αSNAP expression in vivo. Thus, given the critical roles of ECM adhesion in tissue integrity and morphogenesis, it is predictable that loss of αSNAP expression should impair development and survival of multicellular organisms. Indeed previous genetic analysis demonstrated lethality of αSNAP deletion in Drosophila mutants (61). Furthermore, the so-called hyh mutation that decreases αSNAP expression in mice (62, 63) was also shown to impair animal survival and development (64). Interestingly, homozygous hyh mice are characterized by progressive loss of neuroepithelium in brain ventricles (65, 66), which is consistent with the weakening of ECM and cell-cell adhesions of αSNAP-depleted cells.

Another novel and important finding of this study is the role of αSNAP in regulating epithelial cell invasion. The observed relationship between the cellular level of αSNAP and cell invasiveness appears to be non-linear because both depletion and robust overexpression of this trafficking protein decreased cell invasion into Matrigel (Fig. 5 and data not shown). It is well established that ECM adhesion is an important determinant of cell migration; however, relationships between these two processes are complex. Indeed, the most efficient cell migration occurs at intermediate attachment strength and both weak and strong matrix adhesions can inhibit cell motility (67, 68). Therefore, the effects of diminished and enhanced αSNAP expression on cell motility can be explained by distinct cell adhesiveness when either loss of cell-matrix adhesion of αSNAP-deleted cells, or very strong attachment of αSNAP-overexpressing cells, impedes cell movement. This notion is supported by our paxillin depletion experiments that showed reversed hyperadhesiveness of αSNAP overexpressing cells and restored Matrigel invasiveness (Fig. 10, E and F).

Because αSNAP regulates a number of membrane trafficking events in different cellular compartments (69, 70), it can affect ECM adhesion and motility via multiple mechanisms. Two major mechanisms suggested by this study include maturation and trafficking of β1 integrin and regulation of expression/activity of cytoplasmic FA proteins. Indeed, loss of αSNAP resulted in accumulation of incompletely glycosylated β1 integrin and intracellular retention of this ECM receptor (Figs. 2 and 3). The immature β1 integrin appeared to be initially N-glycosylated at the ER, but was not properly glycosylated at the Golgi (Fig. 8). Roles and regulation of integrin glycosylation at the Golgi remain poorly understood and only a few previous studies demonstrated modulation of this process by non-enzymatic mechanisms. For example, depletion of a guanine nucleotide exchange protein, BIG1, impaired Golgi-dependent glycosylation of β1 integrin in hepatocarcinoma cells (71), whereas such integrin maturation was enhanced in embryonic fibroblasts deficient in the catalytic subunits of the γ-secretase complex (72). In these studies, the amount of fully glycosylated β1 integrin positively correlated with avidity of ECM adhesions. In contrast, pharmacological inhibition of Golgi-dependent β1 integrin glycosylation did not recapitulate defects of its targeting to the plasma membrane and decreased cell adhesiveness characteristics off αSNAP depletion (Fig. 8). This highlights a dual role of αSNAP in regulating β1 integrin maturation in the Golgi and its subsequent trafficking to the plasma membrane.

The role of αSNAP in regulating β1 integrin activity on the cell surface is further supported by our finding that inhibitory anti-β1 integrin antibody completely reversed enhanced ECM adhesion of αSNAP-overexpressing SK-CO15 cells and inhibited invasion of cells with different levels of αSNAP expression (Fig. 9, C–E). However, unlike αSNAP knockdown, inhibition of β1 integrin did not induce spontaneous detachment of control SK-CO15 cells (Fig. 9, A and B, and data not shown), which may have a methodological explanation. Thus, MAB13 inhibitory antibody may not be able to access and/or disrupt the established β1 integrin-ECM complexes. On the other hand, siRNA-mediated knockdown of β1 integrin can be functionally compensated by other integrins as has been reported under different experimental conditions (73).

Several lines of evidence in our study indicate that αSNAP regulates epithelial ECM adhesion by controlling assembly of FA. First, loss of αSNAP resulted in disappearance of FA along with inactivation (dephosphorylation) of essential FA proteins, FAK and paxillin (Fig. 2). Second, pharmacological inhibition of FAK family proteins mimicked the effects of αSNAP depletion on cell attachment (Fig. 9). Finally, overexpression of αSNAP increased the protein level and phosphorylation of paxillin (Fig. 5), whereas paxillin knockdown reversed the enhanced ECM adhesion and reduced invasiveness of αSNAP-overexpressing cells (Fig. 10). Interestingly, depletion of paxillin did not affect adhesion or invasion of control SK-CO15 cells. This data likely reflects a functional compensation by other members of the paxillin family, such as leupaxin or Hic-5 (74, 75), and highlights the unique role of paxillin in the pro-adhesive activity of αSNAP. Overall, our results are consistent with previous studies that demonstrated the involvement of different SNAREs in FA assembly as well as FAK expression and activation (26, 33). Although different FA proteins can readily shuttle between plasma membrane and intracellular compartments such as the nucleus (76), mechanisms of trafficking-dependent regulation of FAK and paxillin remain unknown. Loss of αSNAP can indirectly inhibit FAK and paxillin phosphorylation by decreasing the amount of activated integrins at the plasma membrane. Alternatively, αSNAP can directly regulate expression and trafficking of these FA proteins. This last mechanism is supported by reported associations of paxillin with known vesicle trafficking regulators, exocyst and GIT1 (77, 78).

Interestingly, our data strongly suggests that αSNAP modulates epithelial ECM adhesion independently of its key binding partner, NSF. Indeed, the αSNAP L294A mutant, although unable to activate NSF, still significantly enhanced ECM adhesion and paxillin expression/phosphorylation similar to the wild-type protein (Fig. 5). Additionally, unlike αSNAP depletion, loss of NSF neither decreased FAK or paxillin phosphorylation nor diminished cell-matrix attachment (Fig. 6). These intriguing observations add to a growing body of evidence indicating that important cellular functions of αSNAP can be executed via NSF-independent mechanisms. Examples of such NSF-independent functions include regulation of apical plasma membrane trafficking (79) and integrity of apical junctions in polarized epithelial cells (34), as well as control of cell survival (35) and autophagy (36). A recent study has described a novel role of αSNAP in regulating mitochondrial biogenesis via direct interaction and dephosphorylation of AMP-activated protein kinase (37). However, such phosphatase activity is unlikely to be involved in modulation of epithelial ECM adhesion, where αSNAP demonstrates the opposite effect by promoting phosphorylation of FA proteins.

αSNAP was previously identified as a member of two SNARE complexes containing syntaxin-5 and syntaxin-18 (80, 81) that control anterograde and retrograde vesicle trafficking between the ER and Golgi, respectively (82). Also, according to cell-free vesicle reconstitution experiments, αSNAP can mediate both ER to Golgi and intra-Golgi vesicle transport (69, 83). Because a constant bidirectional vesicle trafficking is essential for Golgi integrity, one can expect that loss of αSNAP should impair Golgi morphology and functions. Indeed, our recent studies demonstrate a marked fragmentation of the Golgi and decreased expression of Golgi-resident proteins such as GBF1 in αSNAP-depleted epithelial cells (34–36). Similarly, a loss of function mutation of the brain-enriched βSNAP isoform was shown to trigger Golgi dispersion in zebrafish photoreceptors leading to photoreceptor degeneration (84). Importantly, we observed that Golgi fragmentation by either pharmacologic agents or GBF1 depletion phenocopied all effects of αSNAP knockdown on ECM adhesion including impaired processing and mislocalization of β1 integrin, decreased expression and phosphorylation of paxillin, and cell detachment (Fig. 7). This data highlights Golgi disruption as an important upstream event that mediates disruption of ECM adhesion in αSNAP-depleted epithelial cells. The Golgi-dependent mechanism can explain the severity of the effects of αSNAP knockdown, eventuating in epithelial cell detachment. Indeed, the Golgi is a crucial processing and sorting center for the majority of plasma membrane and secreted proteins. Its disruption would impair not only delivery and plasma membrane assembly of matrix adhesion complexes but also secretion of extracellular matrix proteins, thereby diminishing both receptor and ligand components of cell-matrix interactions.

Much remains to be learned about pathophysiologic implications of αSNAP-dependent alterations of cellular functions including ECM adhesion. No systematic studies of αSNAP tissue expression under pathologic states are available, although some reports demonstrated disease-related alterations in the level of this trafficking protein. For example, increased expression of αSNAP was observed in human colorectal carcinoma, which correlated with poor prognosis of the disease (85). Furthermore, loss of αSNAP expression was detected in the brain of Down syndrome fetuses (86) and in the striatum of patients with Huntington disease (87). Finally, some viral proteins reportedly down-regulate αSNAP levels in tumor cells, thereby sensitizing these cells to death-inducing stimuli (41). This data demonstrates an intriguing possibility that the αSNAP level can serve as a molecular rheostat determining cellular responses and behavior in different pathological conditions. Further studies are warranted to examine possible abnormalities and pathophysiologic roles of αSNAP in various human diseases such as neurodegeneration, inflammation, and cancer.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Enrique Rodriguez-Boulan for providing SK-CO15 cells and Dr. David Brautigan for reagents and insightful comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants RO1 DK083968 and R01 DK084953 (to A. I. I.) and Crohn's and Colitis Foundation of America Grant 254881 (to N. G. N.).

- ECM

- extracellular matrix

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- FA

- focal adhesions

- FAK

- focal adhesion kinase

- NSF

- N-ethylmaleimide sensitive factor

- αSNAP

- soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein α

- SNARE

- soluble NSF attachment protein receptor

- DMJ

- deoxymannojirimycin

- Q-VAD-OPH

- N-(2-quinolyl)valyl-aspartyl-(2,6-difluorophenoxy)methyl ketone.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bryant D. M., Mostov K. E. (2008) From cells to organs. Building polarized tissue. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 887–901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schock F., Perrimon N. (2002) Molecular mechanisms of epithelial morphogenesis. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 18, 463–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Heath J. P. (1996) Epithelial cell migration in the intestine. Cell Biol. Int 20, 139–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Radtke F., Clevers H. (2005) Self-renewal and cancer of the gut. Two sides of a coin. Science 307, 1904–1909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Condeelis J., Singer R. H., Segall J. E. (2005) The great escape. When cancer cells hijack the genes for chemotaxis and motility. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 21, 695–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mammen J. M., Matthews J. B. (2003) Mucosal repair in the gastrointestinal tract. Crit. Care Med. 31, S532–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Huttenlocher A., Horwitz A. R. (2011) Integrins in cell migration. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol. 3, a005074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sheppard D. (1996) Epithelial integrins. Bioessays 18, 655–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wehrle-Haller B. (2012) Structure and function of focal adhesions. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 24, 116–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wolfenson H., Lavelin I., Geiger B. (2013) Dynamic regulation of the structure and functions of integrin adhesions. Dev. Cell 24, 447–458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zebda N., Dubrovskyi O., Birukov K. G. (2012) Focal adhesion kinase regulation of mechanotransduction and its impact on endothelial cell functions. Microvasc. Res. 83, 71–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhao X., Guan J.-L. (2011) Focal adhesion kinase and its signaling pathways in cell migration and angiogenesis. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 63, 610–615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kaverina I., Krylyshkina O., Small J. V. (2002) Regulation of substrate adhesion dynamics during cell motility. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 34, 746–761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ridley A. J., Schwartz M. A., Burridge K., Firtel R. A., Ginsberg M. H., Borisy G., Parsons J. T., Horwitz A. R. (2003) Cell migration. Integrating signals from front to back. Science 302, 1704–1709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Margadant C., Monsuur H. N., Norman J. C., Sonnenberg A. (2011) Mechanisms of integrin activation and trafficking. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 23, 607–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Valdembri D., Serini G. (2012) Regulation of adhesion site dynamics by integrin traffic. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 24, 582–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bonifacino J. S., Glick B. S. (2004) The mechanisms of vesicle budding and fusion. Cell 116, 153–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zerial M., McBride H. (2001) Rab proteins as membrane organizers. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 107–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hong W. (2005) SNAREs and traffic. Biochim Biophys Acta 1744, 120–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Malsam J., Kreye S., Söllner T. H. (2008) Membrane fusion. SNAREs and regulation. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 65, 2814–2832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Day P., Riggs K. A., Hasan N., Corbin D., Humphrey D., Hu C. (2011) Syntaxins 3 and 4 mediate vesicular trafficking of α5β1 and α3β1 integrins and cancer cell migration. Int. J. Oncol. 39, 863–871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Skalski M., Yi Q., Kean M. J., Myers D. W., Williams K. C., Burtnik A., Coppolino M. G. (2010) Lamellipodium extension and membrane ruffling require different SNARE-mediated trafficking pathways. BMC Cell Biol. 11, 62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Luftman K., Hasan N., Day P., Hardee D., Hu C. (2009) Silencing of VAMP3 inhibits cell migration and integrin-mediated adhesion. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 380, 65–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Riggs K. A., Hasan N., Humphrey D., Raleigh C., Nevitt C., Corbin D., Hu C. (2012) Regulation of integrin endocytic recycling and chemotactic cell migration by syntaxin 6 and VAMP3 interaction. J. Cell Sci. 125, 3827–3839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tiwari A., Jung J.-J., Inamdar S. M., Brown C. O., Goel A., Choudhury A. (2011) Endothelial cell migration on fibronectin is regulated by syntaxin 6-mediated α5β1 integrin recycling. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 36749–36761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang Y., Shu L., Chen X. (2008) Syntaxin 6, a regulator of the protein trafficking machinery and a target of the p53 family, is required for cell adhesion and survival. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 30689–30698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Burgoyne R. D., Morgan A. (1998) Analysis of regulated exocytosis in adrenal chromaffin cells. Insights into NSF/SNAP/SNARE function. Bioessays 20, 328–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Whiteheart S. W., Schraw T., Matveeva E. A. (2001) N-Ethylmaleimide sensitive factor (NSF) structure and function. Int. Rev. Cytol. 207, 71–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Andreeva A. V., Kutuzov M. A., Voyno-Yasenetskaya T. A. (2006) A ubiquitous membrane fusion protein αSNAP. A potential therapeutic target for cancer, diabetes and neurological disorders? Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 10, 723–733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhao C., Smith E. C., Whiteheart S. W. (2012) Requirements for the catalytic cycle of the N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor (NSF). Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1823, 159–171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Morrell C. N., Matsushita K., Lowenstein C. J. (2005) A novel inhibitor of N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor decreases leukocyte trafficking and peritonitis. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 314, 155–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Skalski M., Coppolino M. G. (2005) SNARE-mediated trafficking of α5β1 integrin is required for spreading in CHO cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 335, 1199–1210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Skalski M., Sharma N., Williams K., Kruspe A., Coppolino M. G. (2011) SNARE-mediated membrane traffic is required for focal adhesion kinase signaling and Src-regulated focal adhesion turnover. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1813, 148–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Naydenov N. G., Brown B., Harris G., Dohn M. R., Morales V. M., Baranwal S., Reynolds A. B., Ivanov A. I. (2012) A membrane fusion protein αSNAP is a novel regulator of epithelial apical junctions. PLoS One 7, e34320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Naydenov N. G., Harris G., Brown B., Schaefer K. L., Das S. K., Fisher P. B., Ivanov A. I. (2012) Loss of soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein alpha (αSNAP) induces epithelial cell apoptosis via down-regulation of Bcl-2 expression and disruption of the Golgi. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 5928–5941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Naydenov N. G., Harris G., Morales V., Ivanov A. I. (2012) Loss of a membrane trafficking protein αSNAP induces non-canonical autophagy in human epithelia. Cell Cycle 11, 4613–4625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang L., Brautigan D. L. (2013) α-SNAP inhibits AMPK signaling to reduce mitochondrial biogenesis and dephosphorylates Thr-172 in AMPKα in vitro. Nat. Commun. 4, 1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Le Bivic A., Real F. X., Rodriguez-Boulan E. (1989) Vectorial targeting of apical and basolateral plasma membrane proteins in a human adenocarcinoma epithelial cell line. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86, 9313–9317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Naydenov N. G., Hopkins A. M., Ivanov A. I. (2009) c-Jun N-terminal kinase mediates disassembly of apical junctions in model intestinal epithelia. Cell Cycle 8, 2110–2121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ivanov A. I., Bachar M., Babbin B. A., Adelstein R. S., Nusrat A., Parkos C. A. (2007) A unique role for nonmuscle myosin heavy chain IIA in regulation of epithelial apical junctions. PLoS One 2, e658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wu Z.-Z., Chow K.-P. N., Kuo T.-C., Chang Y.-S., Chao C. C. K. (2011) Latent membrane protein 1 of Epstein-Barr virus sensitizes cancer cells to cisplatin by enhancing NF-κB p50 homodimer formation and down-regulating NAPA expression. Biochem. Pharmacol. 82, 1860–1872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Naydenov N. G., Ivanov A. I. (2010) Adducins regulate remodeling of apical junctions in human epithelial cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 21, 3506–3517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Babbin B. A., Koch S., Bachar M., Conti M.-A., Parkos C. A., Adelstein R. S., Nusrat A., Ivanov A. I. (2009) Non-muscle myosin IIA differentially regulates intestinal epithelial cell restitution and matrix invasion. Am. J. Pathol. 174, 436–448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rankin C. R., Hilgarth R. S., Leoni G., Kwon M., Den Beste K. A., Parkos C. A., Nusrat A. (2013) Annexin A2 regulates β1 integrin internalization and intestinal epithelial cell migration. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 15229–15239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Akiyama S. K., Yamada K. M. (1987) Biosynthesis and acquisition of biological activity of the fibronectin receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 262, 17536–17542 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wu Z.-Z., Chao C. C. (2010) Knockdown of NAPA using short-hairpin RNA sensitizes cancer cells to cisplatin. Implications to overcome chemoresistance. Biochem. Pharmacol. 80, 827–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Barnard R. J., Morgan A., Burgoyne R. D. (1997) Stimulation of NSF ATPase activity by alpha-SNAP is required for SNARE complex disassembly and exocytosis. J. Cell Biol. 139, 875–883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jackson C. L. (2000) Brefeldin A revealing the fundamental principles governing membrane dynamics and protein transport. Subcell. Biochem. 34, 233–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sáenz J. B., Sun W. J., Chang J. W., Li J., Bursulaya B., Gray N. S., Haslam D. B. (2009) Golgicide A reveals essential roles for GBF1 in Golgi assembly and function. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5, 157–165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kawamoto K., Yoshida Y., Tamaki H., Torii S., Shinotsuka C., Yamashina S., Nakayama K. (2002) GBF1, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor for ADP-ribosylation factors, is localized to the cis-Golgi and involved in membrane association of the COPI coat. Traffic 3, 483–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Niu T.-K., Pfeifer A. C., Lippincott-Schwartz J., Jackson C. L. (2005) Dynamics of GBF1, a brefeldin A-sensitive Arf1 exchange factor at the Golgi. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 1213–1222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hotchin N. A., Watt F. M. (1992) Transcriptional and post-translational regulation of β1 integrin expression during keratinocyte terminal differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 14852–14858 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Veiga S. S., Chammas R., Cella N., Brentani R. R. (1995) Glycosylation of β1 integrins in B16-F10 mouse melanoma cells as determinant of differential binding and acquisition of biological activity. Int. J. Cancer 61, 420–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Chrispeels M. J., Higgins T. J., Craig S., Spencer D. (1982) Role of the endoplasmic reticulum in the synthesis of reserve proteins and the kinetics of their transport to protein bodies in developing pea cotyledons. J. Cell Biol. 93, 5–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tulsiani D. R., Harris T. M., Touster O. (1982) Swainsonine inhibits the biosynthesis of complex glycoproteins by inhibition of Golgi mannosidase II. J. Biol. Chem. 257, 7936–7939 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Akiyama S. K., Yamada S. S., Chen W. T., Yamada K. M. (1989) Analysis of fibronectin receptor function with monoclonal antibodies. Roles in cell adhesion, migration, matrix assembly, and cytoskeletal organization. J. Cell Biol. 109, 863–875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Tse K. W., Dang-Lawson M., Lee R. L., Vong D., Bulic A., Buckbinder L., Gold M. R. (2009) B cell receptor-induced phosphorylation of Pyk2 and focal adhesion kinase involves integrins and the Rap GTPases and is required for B cell spreading. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 22865–22877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Fletcher S. J., Rappoport J. Z. (2009) The role of vesicle trafficking in epithelial cell motility. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 37, 1072–1076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hendrix A., Westbroek W., Bracke M., De Wever O. (2010) An ex(o)citing machinery for invasive tumor growth. Cancer Res. 70, 9533–9537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Jung J.-J., Inamdar S. M., Tiwari A., Choudhury A. (2012) Regulation of intracellular membrane trafficking and cell dynamics by syntaxin-6. Biosci. Rep. 32, 383–391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Babcock M., Macleod G. T., Leither J., Pallanck L. (2004) Genetic analysis of soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein function in Drosophila reveals positive and negative secretory roles. J. Neurosci. 24, 3964–3973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Chae T. H., Kim S., Marz K. E., Hanson P. I., Walsh C. A. (2004) The hyh mutation uncovers roles for αSnap in apical protein localization and control of neural cell fate. Nat. Genet. 36, 264–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hong H.-K., Chakravarti A., Takahashi J. S. (2004) The gene for soluble N-ethylmaleimide sensitive factor attachment protein α is mutated in hydrocephaly with hop gait (hyh) mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 1748–1753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Bátiz L. F., Páez P., Jiménez A. J., Rodríguez S., Wagner C., Pérez-Fígares J. M., Rodríguez E. M. (2006) Heterogeneous expression of hydrocephalic phenotype in the hyh mice carrying a point mutation in α-SNAP. Neurobiol. Dis. 23, 152–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ferland R. J., Batiz L. F., Neal J., Lian G., Bundock E., Lu J., Hsiao Y.-C., Diamond R., Mei D., Banham A. H., Brown P. J., Vanderburg C. R., Joseph J., Hecht J. L., Folkerth R., Guerrini R., Walsh C. A., Rodriguez E. M., Sheen V. L. (2009) Disruption of neural progenitors along the ventricular and subventricular zones in periventricular heterotopia. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18, 497–516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Roales-Buján R., Páez P., Guerra M., Rodríguez S., Vío K., Ho-Plagaro A., García-Bonilla M., Rodríguez-Pérez L. M., Domínguez-Pinos M. D., Rodríguez E. M., Pérez-Fígares J. M., Jiménez A. J. (2012) Astrocytes acquire morphological and functional characteristics of ependymal cells following disruption of ependyma in hydrocephalus. Acta Neuropathol. 124, 531–546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. DiMilla P. A., Stone J. A., Quinn J. A., Albelda S. M., Lauffenburger D. A. (1993) Maximal migration of human smooth muscle cells on fibronectin and type IV collagen occurs at an intermediate attachment strength. J. Cell Biol. 122, 729–737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Gupton S. L., Waterman-Storer C. M. (2006) Spatiotemporal feedback between actomyosin and focal-adhesion systems optimizes rapid cell migration. Cell 125, 1361–1374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Clary D. O., Griff I. C., Rothman J. E. (1990) SNAPs, a family of NSF attachment proteins involved in intracellular membrane fusion in animals and yeast. Cell 61, 709–721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Whiteheart S. W., Brunner M., Wilson D. W., Wiedmann M., Rothman J. E. (1992) Soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion attachment proteins (SNAPs) bind to a multi-SNAP receptor complex in Golgi membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 12239–12243 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Shen X., Hong M.-S., Moss J., Vaughan M. (2007) BIG1, a brefeldin A-inhibited guanine nucleotide-exchange protein, is required for correct glycosylation and function of integrin β1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 1230–1235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Zou K., Hosono T., Nakamura T., Shiraishi H., Maeda T., Komano H., Yanagisawa K., Michikawa M. (2008) Novel role of presenilins in maturation and transport of integrin β1. Biochemistry 47, 3370–3378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Parvani J. G., Galliher-Beckley A. J., Schiemann B. J., Schiemann W. P. (2013) Targeted inactivation of beta1 integrin induces β3 integrin switching, which drives breast cancer metastasis by TGF-β. Mol. Biol. Cell 24, 3449–3459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Chen P.-W., Kroog G. S. (2010) Leupaxin is similar to paxillin in focal adhesion targeting and tyrosine phosphorylation but has distinct roles in cell adhesion and spreading. Cell Adh. Migr. 4, 527–540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Deakin N. O., Turner C. E. (2011) Distinct roles for paxillin and Hic-5 in regulating breast cancer cell morphology, invasion, and metastasis. Mol. Biol. Cell 22, 327–341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Hervy M., Hoffman L., Beckerle M. C. (2006) From the membrane to the nucleus and back again. Bifunctional focal adhesion proteins. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 18, 524–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Manabe R., Kovalenko M., Webb D. J., Horwitz A. R. (2002) GIT1 functions in a motile, multi-molecular signaling complex that regulates protrusive activity and cell migration. J. Cell Sci. 115, 1497–1510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Spiczka K. S., Yeaman C. (2008) Ral-regulated interaction between Sec5 and paxillin targets Exocyst to focal complexes during cell migration. J. Cell Sci. 121, 2880–2891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Low S. H., Chapin S. J., Wimmer C., Whiteheart S. W., Kömüves L. G., Mostov K. E., Weimbs T. (1998) The SNARE machinery is involved in apical plasma membrane trafficking in MDCK cells. J. Cell Biol. 141, 1503–1513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Aoki T., Kojima M., Tani K., Tagaya M. (2008) Sec22b-dependent assembly of endoplasmic reticulum Q-SNARE proteins. Biochem. J. 410, 93–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Rabouille C., Kondo H., Newman R., Hui N., Freemont P., Warren G. (1998) Syntaxin 5 is a common component of the NSF- and p97-mediated reassembly pathways of Golgi cisternae from mitotic Golgi fragments in vitro. Cell 92, 603–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Jahn R., Scheller R. H. (2006) SNAREs–engines for membrane fusion. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 631–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Peter F., Wong S. H., Subramaniam V. N., Tang B. L., Hong W. (1998) α-SNAP but not γ-SNAP is required for ER-Golgi transport after vesicle budding and the Rab1-requiring step but before the EGTA-sensitive step. J. Cell Sci. 111, 2625–2633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Nishiwaki Y., Yoshizawa A., Kojima Y., Oguri E., Nakamura S., Suzuki S., Yuasa-Kawada J., Kinoshita-Kawada M., Mochizuki T., Masai I. (2013) The BH3-only SNARE BNip1 mediates photoreceptor apoptosis in response to vesicular fusion defects. Dev. Cell 25, 374–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Grabowski P., Schönfelder J., Ahnert-Hilger G., Foss H.-D., Heine B., Schindler I., Stein H., Berger G., Zeitz M., Scherübl H. (2002) Expression of neuroendocrine markers. A signature of human undifferentiated carcinoma of the colon and rectum. Virchows Arch. 441, 256–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Weitzdoerfer R., Dierssen M., Fountoulakis M., Lubec G. (2001) Fetal life in Down syndrome starts with normal neuronal density but impaired dendritic spines and synaptosomal structure. J. Neural Transm. Suppl. 61, 59–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Morton A. J., Faull R. L., Edwardson J. M. (2001) Abnormalities in the synaptic vesicle fusion machinery in Huntington's disease. Brain Res. Bull. 56, 111–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]