Abstract

Polycystic ovary syndrome is a common endocrine disorder in females of reproductive age and is believed to have a developmental origin in which gestational androgenization programs reproductive and metabolic abnormalities in offspring. During gestation, both male and female fetuses are exposed to potential androgen excess. We determined the consequences of developmental androgenization in male mice exposed to neonatal testosterone (NTM). Adult NTM displayed hypogonadotropic hypogonadism with decreased serum testosterone and gonadotropins. Hypothalamic KiSS1 neurons are believed to be critical in the onset of puberty and are the target of leptin. Adult NTM showed lower hypothalamic Kiss1 expression and a failure of leptin to upregulate Kiss1 expression. NTM displayed an early reduction in lean mass, decreased locomotor activity and decreased energy expenditure. They developed a delayed increase in subcutaneous white adipose tissue. Thus, excessive neonatal androgenization disrupts reproduction and energy homeostasis and predisposes to hypogonadism and obesity in adult male mice.

Keywords: Androgens, Reproduction, Energy homeostasis

Introduction

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most common endocrine disorder in females of reproductive age and is believed to have a developmental origin in which maternal and fetal androgen excess during pregnancy programs both the reproductive and metabolic abnormalities of the offspring.(Abbott, et al. 2005; Xita and Tsatsoulis 2006, 2010) Female primates and rodents exposed to androgen excess during critical periods of perinatal development go on to develop a predominantly visceral fat accumulation with accompanying insulin resistance during adulthood.(Alexanderson, et al. 2007; Eisner, et al. 2003; Nilsson, et al. 1998) During fetal life, both male and female fetuses are exposed to a potential source of androgen excess. In fact, brothers of women with PCOS develop insulin resistance compared to control men, (Sam, et al. 2008; Yildiz, et al. 2003) an observation that is compatible with the hypothesis involving a common developmental origin characterized by excess androgen exposure. In addition, male primates exposed to prenatal androgen excess exhibit insulin resistance as adults, emulating prenatally exposed females.(Bruns, et al. 2004) Furthermore, male sheep and rats exposed to prenatal androgen excess develop signs of hypogonadism and feminization.(Recabarren, et al. 2008; Wolf, et al. 2002) The issue of developmental androgenization is of critical importance and should be getting more attention because of increasing human exposure to environmental factors that interact with androgen and estrogen receptor systems.(Chen, et al. 2008; Hotchkiss, et al. 2007) An obvious question arises as to whether developmental exposure to androgen from endogenous or exogenous sources could program both reproductive and metabolic abnormalities in male offspring as they do in females. There is extensive evidence supporting brain programming of behavior and physiology by perinatal testosterone.(Arnold and Gorski 1984; MacLusky and Naftolin 1981; Morris, et al. 2004; Negri-Cesi, et al. 2008; Simerly 2002; Wu, et al. 2009) For example, the Kiss1 gene encodes for kisspeptins that are instrumental in triggering puberty.(d'Anglemont de Tassigny, et al. 2007; Seminara, et al. 2003) Male rodents express lower levels of Kiss1 in the hypothalamus and in females, perinatal testosterone exposure suppresses Kiss1 expression, thereby preventing the pre-ovulatory surge of gonadotropin.(Kauffman, et al. 2007) Human and non-human primates are precocial species that give birth to mature young. In both groups, synaptogenesis of hypothalamic centers that control energy homeostasis and adipose tissue development occur during the second trimester of pregnancy.(Ailhaud, et al. 1992; Gesta, et al. 2007; Koutcherov, et al. 2002) In contrast, the mouse is an altricial species that gives birth to immature young. In mice, development of hypothalamic circuits that control adiposity and adipose tissue occur during the first two weeks of neonatal life.(Ailhaud et al. 1992; Bouret, et al. 2004; Gesta et al. 2007) Testosterone mediates many aspects of sexual differentiation of the male rodent brain during a restricted developmental neonatal period ending on day ten.(Arnold and Gorski 1984; MacLusky and Naftolin 1981) Thus, during a critical period corresponding to late pregnancy in humans, androgen excess could program reproductive and metabolic abnormalities that would later appear in adult male rodents. In this report, we used the male mouse model neonatally androgenized with testosterone as a means to understand the role of developmental androgen excess-induced reproductive and metabolic abnormalities in males.

Materials and methods

Animals

Mice neonatally injected with testosterone (NT) were produced by injecting C57BL/6 pups with 100 µg testosterone enanthate (Steraloids, Inc. Newport RI) subcutaneously in the neck in sesame oil (volume 20 µl) at neonatal days one and two (birth date= day 0). Control pups of the same age were injected with vehicle in sesame oil. Mice were fed a standard rodent chow (Harlan Teklad, code 7912). All animal experiments were approved by Northwestern University Animal Care and Use Committee in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Animals.

Metabolic studies

Serum leptin and adiponectin levels were measured by ELISA (Linco Research, Inc. St. Louis, MO). Serum testosterone (Siemens Medical Solutions Diagnostics. Los Angels CA), estradiol (Beckman coulter, Inc. Fullerton CA) and FSH levels were measured by RIA.(Gay, et al. 1970) Serum LH levels were measured by sandwich ELISA.(Haavisto, et al. 1993)

Gene expression analysis by real-time quantitative PCR

Gene expression was quantified in tissues by real-time quantitative PCR and normalized to β-actin expression. Briefly, total RNA was extracted in TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). One microgram of RNA was reversed transcribed using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories) with random hexamers. Primer sequences are available upon request.

In vivo leptin stimulation

Mice were separated into individual cages for one week to acclimate. Food intake was measured daily for one week to obtain basal values. Leptin (25µg/20g i.p.; National Hormone and Peptide Program (NHPP)) was injected daily for 4 days. During this period, food intake and body weight were measured daily. For hypothalamic Kiss1 expression studies, PBS or leptin (3 µg/g) were injected i.p. after a 24-h fast. Six hours later, mice were sacrificed and hypothalami were isolated. Hypothalami were then frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80°C until assayed.

Fertility test

Fertility was assessed by mating experimental males with C57BL/6 females purchased from Jackson laboratory. Mating occurred for a 30-day period and pairs were monitored regularly for signs of pregnancy. The pregnancy ratio was calculated by the number of pregnant female mice undergoing parturition over the total female mice in each group.

Measurement of adipocyte size

Perigonadal adipose tissue was fixed in 10% formalin (v/v; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) embedded in paraffin, sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Adipocyte surface area was quantified from H&E stained adipose tissue sections using the Image J software (National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD). The mean adipocyte surface area (size) was calculated from 600 cells per mouse. We used an average of 4 mice per group.

Euglycemic hyperinsulinemic clamp

The rate of whole body glucose utilization (mg/kg*min) was determined in hyperinsulinemic euglycemic conditions (5.5mM) as described. Insulin was infused at a rate of 18mU/kg.min for 3 hours and HPLC purified D-(3H)3-glucose (NEN LifeScience, Boston, MA) was simultaneously infused at rate of 30µCi/kg.min to ensure a detectable plasma D-(3H)3-glucose enrichment. Throughout the infusion, blood glucose was assessed from blood samples (1.5 µl) collected from the tip of the tail vein when needed using a blood glucose meter. Euglycemia was maintained by periodically adjusting a variable infusion of 16.5 % glucose. Plasma glucose concentrations, and D-(3H)3-glucose specific activity were determined in 5µl of blood sampled from the tip of the tail vein using heparinised micro-capillaries each 10 minutes during the last hour of the infusion.

Indirect calorimetry

Respiratory metabolism was measured by indirect calorimetry using the Oxymax Comprehensive Laboratory Animal Monitoring System (CLAMS; (Columbus Instruments. Mice were evaluated for oxygen consumption (VO2) and carbon dioxide production (VCO2) over a 24h period. Heat production (Kcal/hour) was calculated according to the following formula = [VO2 × (3.815 + 1.232 × RQ)].

Locomotor activity was assessed by the infrared beam break method using an Opto-Varimetrix-3 sensor system, and water intake was measured with the Feed-Scale System (Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH).

Food intake measurement

Animals were housed individually for 1 week to accommodate to the new environment. Food intake was measured daily for 1 week following accommodation. For measurement of food intake following prolonged fasting, mice were fasted for 24 hours and food intake was measured at the indicated time points.

Osteocalcin levels measurement

Serum Osteocalcin levels were measured by ELISA as described.(Ferron, et al. 2010) GLU13 OCN (active form) levels were calculated by subtraction of GLA13 OCN (inactive form) levels from total OCN levels.

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as mean ± SEM unless otherwise stated. Data were analyzed using the unpaired Student’s t test. A value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism and altered hypothalamic KiSS1 regulation in NTM mice

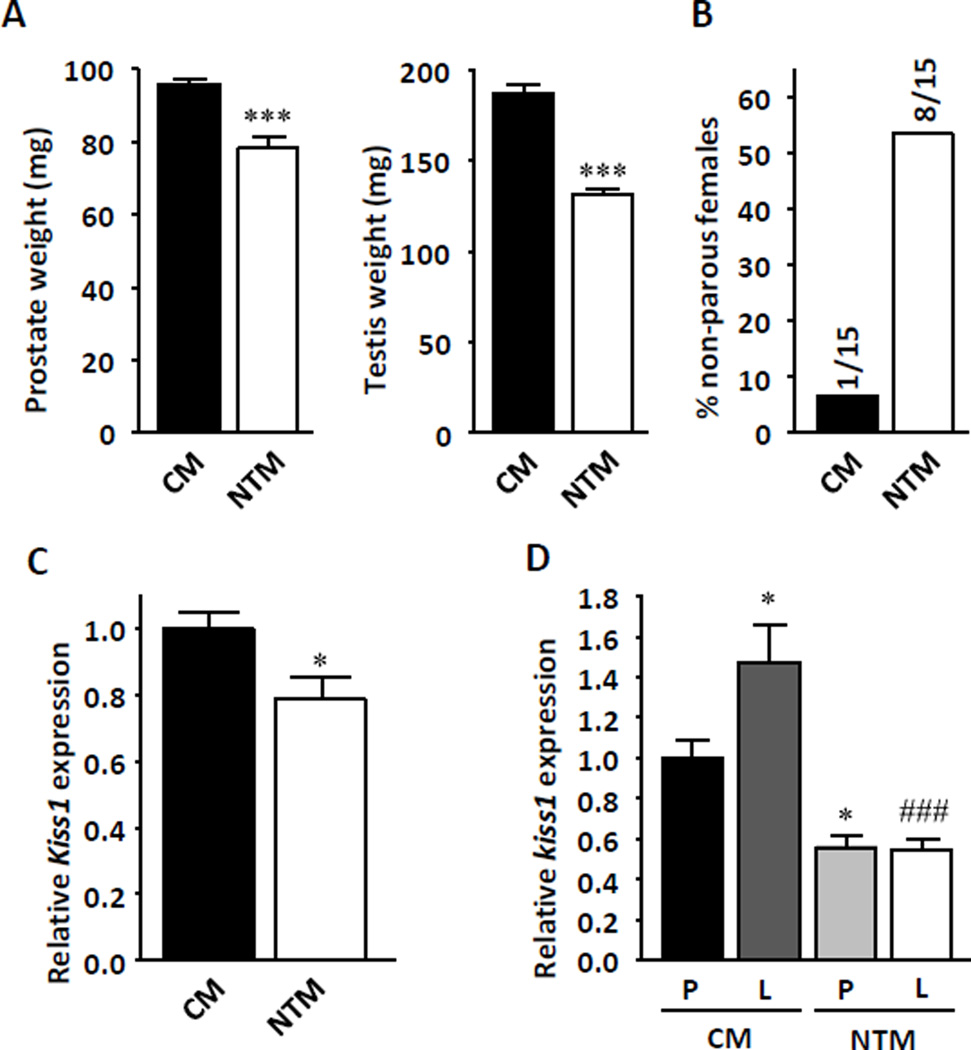

To determine the pathophysiological consequences of neonatal androgenization on reproduction and metabolism in males, we compared littermate control male mice (CM) with male mice exposed to neonatal testosterone (NTM). We used testosterone enanthate to induce prolonged testosterone exposure for two weeks. Adult NTM displayed hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism compared with CM, with small testes and prostate (Figure 1a), decreased serum testosterone, gonadotropin luteinizing hormone (LH), and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). No change was observed in 17β-estradiol (E2) levels (Table 1). As expected, NTM were less fertile than CM (Figure 1b).We previously showed that NT exposure in female mice suppresses hypothalamic Kiss1 expression to levels observed in CM.(Nohara, et al. 2011) KiSS1 neurons of the hypothalamus are believed to be a major trigger of puberty onset (Navarro and Tena-Sempere 2012) and mice lacking a functional Kiss1 gene develop hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism (d'Anglemont de Tassigny et al. 2007) like NTM. Thus, to explain the central hypogonadism, we quantified hypothalamic Kiss 1 expression. As expected, NTM had lower hypothalamic Kiss1 mRNA expression than CM (Figure 1c). KiSS1 neurons of the hypothalamus are also the target of leptin.(Tena-Sempere 2006) Ob/Ob mice are leptin-deficient and exhibit lower hypothalamic Kiss1 expression, a phenotype that can be rescued by leptin injection.(Smith, et al. 2006) We therefore tested leptin’s ability to upregulate hypothalamic Kiss1 expression in NTM mice. Under fasting conditions, NTM displayed lower hypothalamic Kiss1 expression than CM (Figure 1d). Leptin successfully increased hypothalamic Kiss1 expression in CM. However, it failed to upregulate Kiss1 expression in NTM (Figure 1d).

Figure 1. NT programs hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism.

(a) Prostate and testis weight were measured at 20 weeks (n=8–13) (b) Percentage of non-parous females after 1 month mating with CM and NTM. (c) Kiss1 expression in whole mouse hypothalami after refeeding in 10–12 week-old mice (n=11–18). Results represent the mean ± SE. *p< 0.05; ***p<0.001; CM vs. NTM. (d) Kiss1 expression in whole hypothalami after 24hours fasting followed by 6hours 3µg/g i.p. leptin exposure in 20 week-old mice (n=8–9). Results represent the mean ± SE. *p< 0.05; CM vehicle vs CM leptin or NTM vehicle, and ###p<0.001; CM leptin vs NTM leptin.

Table 1.

Serum sex steroid hormone concentrations

| CM | NTM | |

|---|---|---|

| Testosterone (ng/dl) | 34.9 ± 4.3 | 23.6± 2.7* |

| LH (ng/ml) | 0.15 ± 0.03 | 0.09 ± 0.01* |

| FSH (ng/ml) | 33.3 ± 1.4 | 19.0 ± 1.6*** |

| E2 (pg/ml) | 24.7 ± 2.5 | 26.7 ± 2.7 |

Serum testosterone (n=16–25), LH (n=13), FSH (n=5–8) and Estradiol (n=19–23) levels

Values represent mean ± SE.

p< 0.05;

P<0.001.

NTF, CM vs CF. n=3–11 (12 weeks old).

Altered energy homeostasis and body composition in NTM mice

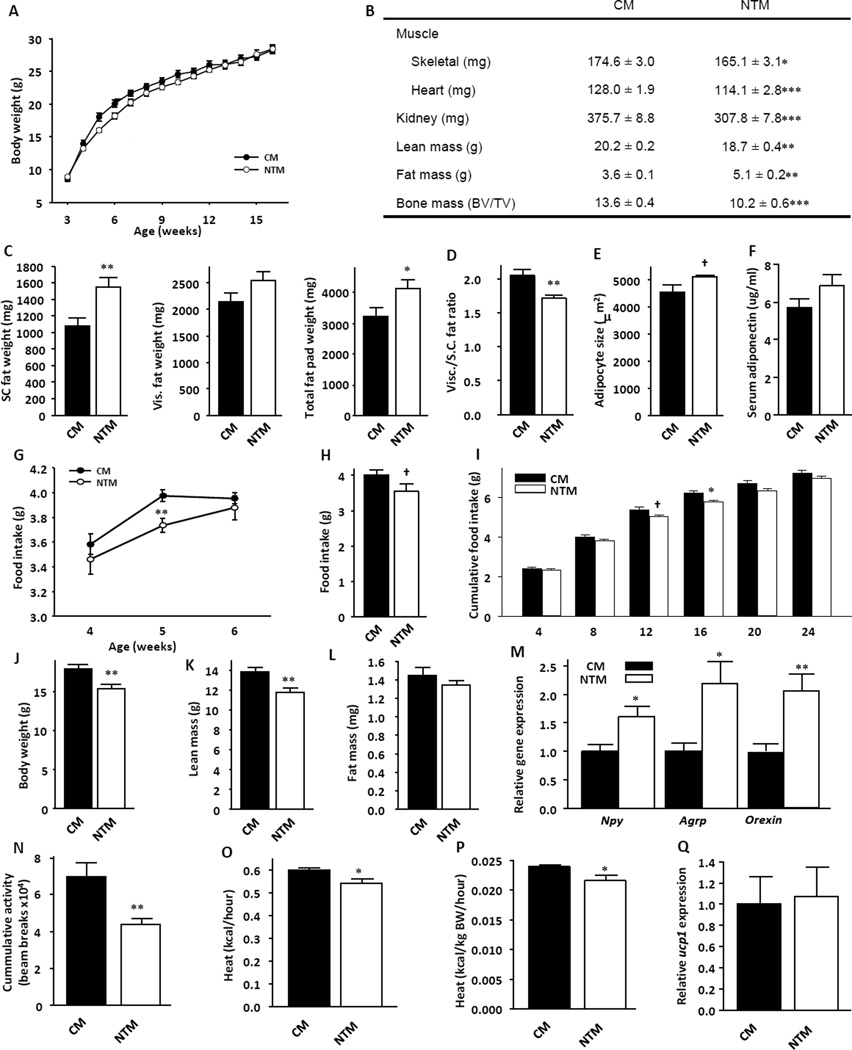

NTM displayed an alteration in body composition characterized by lower body weight in early life, followed by accelerated growth leading to normal body weight in adulthood (Figure 2a). At 44 weeks of age, body weight did not differ between the groups (CM: 32.9 ± 1.1; NTM: 33.5 ± 0.9; Mean ± SE). However, adult NTM had reduced lean mass, including skeletal muscle, heart, kidney and bone, accompanied by increased fat mass (Figure 2b). The increased fat pad weight was observed mostly in subcutaneous (SC) fat without parallel increases in visceral fat depots (Figure 2c). This resulted in relative decreased index of visceral fat consistent with a feminized fat distribution (Figure 2d). Although overall adiposity increased in NTM, adipocyte size did not change significantly in NTM compared with their CM counterparts (Figure 2e). Adiponectin is decreased in obesity(Weyer, et al. 2001) and in littermate NT female mice. (Nohara, et al. 2013) Despite higher adiposity, serum adiponectin was not non-significantly increased in NTM, consistent with the absence of visceral adiposity and large adipocytes (Figure 2f).

Figure 2. NT alters body composition and programs physical activity and energy balance.

(a) Body weight from CM and NTM mice were measured at the indicated time points (n=8–13). (b) Skeletal muscle, heart, kidney weight and bone mass were measured at 20 weeks (n=7–13), total lean mass and total fat mass were measured by NMR (n=8–13). (c) Isolated SC fat pad weight, visceral fat pad weight and total fat pad weight were measured at 32 weeks, and (d) calculated the Visceral/SC fat pad ratio (n=17). (e) WAT adipocyte size (n=4). (f) serum adiponectin (g) Food intake in young mice at the indicated age (n=12–13). (h) Daily food intake in 12 week-old mice (n=8). (i) Cumulative food intake following 24hours fasting in 12–13 week-old mice (n=7–13). (j) Body weight, (k) total lean mass and (l) total fat mass measured in 4 week-old mice (n=9–13). (m) Npy, Agrp and Orexin expression measured by Q-PCR in whole hypothalami after refeeding in 10–12 week-old mice (n=10–12). (n) Locomotor activity was assessed by the infrared beam break method in 10–12 week-old mice (n=8). (o) Energy expenditure was measured by indirect calorimetry in 10–12 week-old mice (n=8). (p) Energy expenditure/total body weight (kcal/g/hour) in 10–12 week-old mice (n=8). (q) Ucp1 expression in BAT in fed condition in 10–12 week-old mice (n=7–9) Results represent the mean ± SE. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.007; †p<0.1, CM vs. NTM.

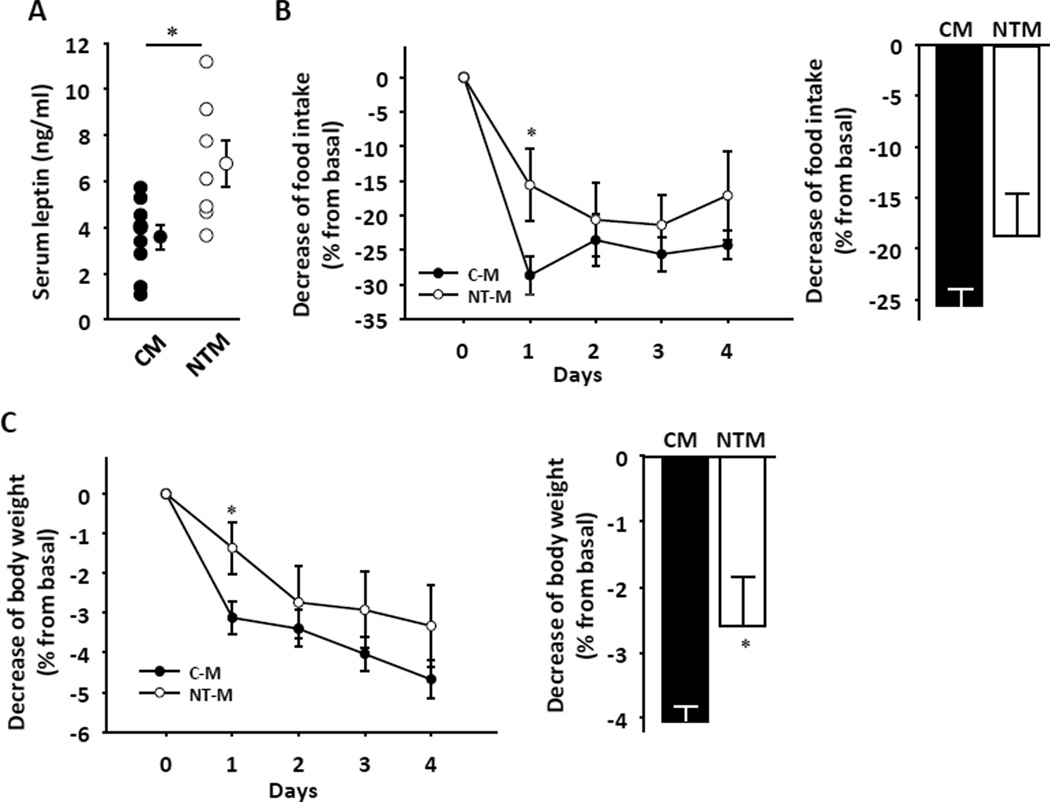

NTM displayed hypophagia at 5 weeks, and a trend toward decreased food intake in adulthood (Figure 2g and h). Decreased food intake was more apparent in adult NTM following a 24 hour fast (Figure 2i). Consistent with the early decrease in food intake, at 5 weeks NTM showed decreased body weight with reduced lean mass, but no alteration in fat mass (Figure 2j-l). Also consistent a primary decrease in food intake, the hypothalamic orexigenic neuropeptides Npy, Agrp and Orexin (Figure 2m) were upregulated, probably as a compensatory mechanism. Conversely, the expression of anorexigenic factors Pomc/Cart, Mc4r and Mch were unaltered (Supplemental figure 1a–d). NTM showed decreased locomotor activity (Figure 2n) and lower energy expenditure (Figure 3o) even when these measures were normalized for total body mass (Figure 2p). Since expression of the uncoupling protein-1 (Ucp1) in BAT was normal (Figure 2q), the decreased energy expenditure appeased to be a consequence of reduced lean mass and locomotor activity. Consistent with increased adiposity, in adults, serum leptin levels were increased in NTM compared to CM (Figure 3a), suggesting a state of leptin resistance. To evaluate leptin sensitivity in these mice, we performed an I.P. leptin tolerance test (LTT). Consistent with the hyperleptinemia, one day after leptin injection, NTM exhibited a failure of leptin to decrease food intake and suppress body weight (Figure 3b and c). The effect of leptin on the level of expression of first order neuropeptides mRNA Pomc, Cart, Npy and Agrp was not contributive (Supplemental Figure 2a).

Figure 3. NT alters leptin sensitivity.

(a) Serum leptin levels were measured at 20 weeks (n=8–13). (b) Suppression of food intake and (c) reduction of body weight were assessed daily for 4 d after ip leptin injection (25µg/20 g/day) in 12-wk-old mice. Daily values (left) and 4 days averages (right) are shown (n=7–15). Results represent the mean ± SE. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; †p<0.1. CM vs. NTM.

Normal glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity in NTM mice

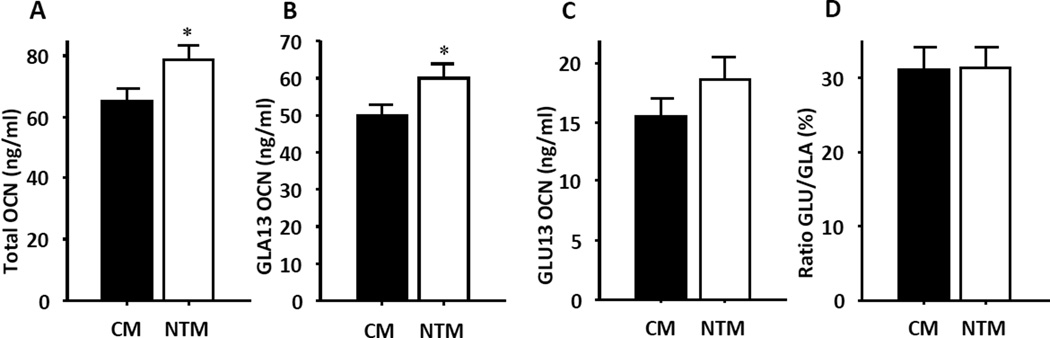

Adult NTM showed no significant alteration in blood glucose or insulin concentration in either the fasting or ad libidum states (Table 2). They exhibited similar insulin sensitivity in euglycemic, hyperinsulinemic clamp conditions than CM (Table 2). Thus, NTM exhibited a normal response to glucose loading (Table 2). Recently, bone-derived osteocalcin has been identified as an endocrine regulator of adiponectin production.(Lee, et al. 2007) Osteocalcin is present in the serum in carboxylated and undercarboxylated forms, yet only the undercarboxylated form of osteocalcin acts as a hormone.(Ferron, et al. 2008; Lee et al. 2007) We recently observed that neonatally androgenized female mice displayed decreases in both undercarboxylated and active osteocalcin.(Nohara et al. 2013) In the current study, we observed an increase in total osteocalcin in NTM (Figure 4). However, NTM also displayed increases in the carboxylated, inactive form of osteocalcin, GLA13 and to a lesser extent, increases in the undercarboxylated, active form of osteocalcin, GLU13 (Figure 4). As a result, there was no difference in the ratio of active: inactive osteocalcin between groups. We also recently reported that female NT mice developed hypertension.(Nohara et al. 2013) In contrast, NTM showed normal systolic and diastolic blood pressures and heart rate (Suppl. Table 1).

Table 2.

Metabolic parameters of glucose metabolism

| CM | NTM | |

|---|---|---|

| Fasting glucose (mg/dl) | 112.7 ± 5.78 | 117.8 ± 7.10 n.s. |

| Fed glucose (mg/dl) | 231.4 ± 8.49 | 240.0 ± 12.86 n.s. |

| Fasting insulin (ng/ml) | 0.34 ± 0.02 | 0.42 ± 0.04 n.s. |

| Fed insulin (ng/ml) | 2.78 ± 0.30 | 2.80 ± 0.36 n.s. |

| Clamp GIR (mg/kg.min) | 86.22 ± 7.05 | 87.83 ± 7.86 n.s. |

| 4month GTT AUC (mg/dl/min*1000) | 16.91 ± 1.02 | 16.45 ± 0.88 n.s. |

GTT: glucose tolerance test.

Values represent mean ± SE.

p=0.070,

p< 0.05.

CM vs. NTM. n=3–27.

Figure 4. NT programs osteocalcin activity.

(a) Total osteocalcin levels, (b) inactive form of osteocalcin GLA13 levels, (c) active form of osteocalcin GLU13 levels and (d) ratio of GLU/GLA (n=11–14). Results represent the mean ± SE. *p< 0.05.

Discussion

In male mammals including humans, the testes produce two perinatal testosterone surges that are critical to masculinize the organism.(Corbier, et al. 1992) Here, we used testosterone enanthate to induce two weeks of prolonged non-physiological testosterone exposure in neonatal male mice. Developmental exposure to androgen in males programs KiSS1 neuron dysfunction that is characterized by lower hypothalamic Kiss1 expression and failure of leptin to stimulate hypothalamic Kiss1 expression. This is associated with hypothalamic hypogonadism with testosterone deficiency and late onset subcutaneous adiposity without features of insulin resistance.

The importance of kisspeptin in controlling the onset of puberty was initially suggested by the observation that inactivating mutations of their G protein-coupled receptor GPR54 prevented the onset of puberty in humans and mice.(Seminara et al. 2003) In addition, mice without functional Kiss1 develop hypothalamic hypogonadism. (d'Anglemont de Tassigny et al. 2007) Further, administering an antagonist to kisspeptin actions delays puberty in female mice.(Pineda, et al. 2010) Thus, although we did not assess the timing of puberty in neonatally androgenized male mice, decreased hypothalamic Kiss1 expression is likely to be instrumental in the development of hypothalamic hypogonadism with decreased gonadotropins, androgen deficiency, and decreased fertility. One limitation of our approach is the quantification of Kiss 1 mRNA in whole hypothalamus. Kiss1 expression in rodent in located in two populations of hypothalamic neurons in the AVPV and ARC. However, male rodents have dramatically lower level of Kiss1 expression in the AVPV compared to females (Kauffman, et al. 2007)

Leptin has been considered a candidate for the metabolic regulation of Kiss1 neurons.(Tena-Sempere 2006) Obese leptin deficient ob/ob mice are infertile. (Chehab, et al. 1996) In these mice, leptin replacement increases Kiss1 expression in the ARC(Smith et al. 2006) and restores fertility.(Chehab, et al. 1996) Neonatally androgenized male mice exhibit a decreased hypothalamic Kiss1 expression. They also develop a failure of leptin to upregulate Kiss1 expression. This supports the hypothesis that neonatal exposure to excess testosterone has either decreased Kiss1 neuronal cell number or programmed an acquired leptin resistance to stimulate Kiss1 expression, thereby leading to a central hypogonadism. The current experiments were not designed to determine whether alteration in Kiss1 expression occurred in KiSS1 or afferent neurons. Indeed, previous evidence suggested that leptin acts directly on KiSS1 neurons – that express leptin receptor (LepR) – to control Kiss1 function.(Smith et al. 2006) More recent evidence, however, suggests that the mode of action of leptin on KiSS1 neurons is indirect, supported by the observation that genetic deletion of LepR selectively from hypothalamic KiSS1 neurons in mice has no effect on puberty and fertility.(Donato, et al. 2011) However, reexpression of LepR in premammillary nucleus (PMV) neurons in the LepR null mice was sufficient to induce puberty. In addition, an unidentified population of LepRb neurons has been identified in close contact with, but afferent to ARC and anteroventral periventricular KiSS1 neurons.(Louis, et al. 2011) Thus, neonatal androgenization may also have programmed leptin resistance in KiSS1 afferent neurons.

We previously observed that neonatal testosterone exposure in female mice programs alteration of Kiss1 neuronal function, leptin resistance, increased energy intake and increased visceral adiposity in adults (Nohara et al. 2011; Nohara et al. 2013). In contrast, neonatally androgenized adult male mice exhibit decreased energy intake, decreased locomotor activity and predominant SC fat deposition. Decreased food intake is probably a primary event since it is observed early in life, and is associated with a compensatory but inefficient increase in hypothalamic orexigenic neuropeptides without alteration in anorexigenic neuropeptides. Decreased lean mass is also present early–at 4 weeks–a time when no fat accumulation is observed. This finding supports the hypothesis that decreases in food intake, lean mass and locomotor activity are collectively linked to a demasculinization of behavior and appear first. These characteristics then produce a secondary decrease in energy expenditure that favors the accumulation of SC fat. It is likely that this phenotype of demasculinization of behavior and body composition is secondary to androgen deficiency. Indeed, a phenotype of disrupted energy homeostasis and fat distribution similar to that of neonatally androgenized male mice is observed in androgen receptor (AR) knockout mice. These mice exhibit reduced spontaneous activity, decreased energy expenditure and a predominant SC fat accumulation.(Fan, et al. 2005; Sato, et al. 2003) Moreover, male mice lacking DNA binding-dependent AR signaling show decreased lean mass and food intake with reduced voluntary activity, and they develop a predominant increase in SC fat without accompanying changes in insulin sensitivity. Further, in both cases, adiponectin is increased in a manner similar to neonatally androgenized male mice.(Fan et al. 2005; Rana, et al. 2011) The absence of decreased or increased adiponectin levels might help retain insulin sensitivity and glucose homeostasis in NTM as in AR knockout mice.

Neonatally androgenized female mice develop many of the features of metabolic syndrome observed in women with PCOS.(Nohara et al. 2011; Nohara et al. 2013) These features include increased food intake and lean mass, visceral adiposity with enlarged adipocytes, hypoadiponectinemia, decreased osteocalcin activity, insulin resistance, pre-diabetes and hypertension. In contrast, littermate male mice develop a mild metabolic phenotype with decreased lean mass and food intake and SC adiposity without cardiometabolic alterations. This observation underscores the potential for sex differences in metabolic diseases arising from the complements of sex-linked genes outside the testis-determining gene Sry.

This study has clinical relevance on a number of levels. A recent study found significant androgen activity in 35% of water sources from several states in the U.S., suggesting that, at least in certain areas, there is a high risk for human exposure to androgens that may result in alterations of the fetal or neonatal environment.(Stavreva, et al. 2012) This relatively wide-spread androgen contamination from pharmaceutical and other sources is of increasing concern. There is a need for in vivo models to test the pathophysiological relevance of such contamination. The model explored here–a neonatal exposure to androgen at supraphysiological doses in male mice–represents a novel tool that may be of potential value in testing for clinically relevant water contamination in in vivo models.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge the cores of the University of Virginia Center for Research in Reproduction (NICHD grant U54-HD28934) for measurement of gonadal hormones, the Rodent Metabolic Phenotyping Core of Northwestern Comprehensive Center on Obesity for measurements of body composition and the Seattle Mouse Metabolic Phenotype Core (MMPC grant U24-DK076126) for measurement of energy expenditure.

FMJ receives research support from Pfizer Inc.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from National Institutes of Health (P50 HD044405, RO1 DK074970-01) and the March of Dimes (6-FY07-678).

Footnotes

Competing financial interests: All other authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions

KN, FMJ designed experiments; KN, SL, MSM, AW, MF performed experiments; KN, GK, RB, and FMJ analyzed data; KN, FMJ wrote the paper.

Reference

- Abbott DH, Barnett DK, Bruns CM, Dumesic DA. Androgen excess fetal programming of female reproduction: a developmental aetiology for polycystic ovary syndrome? Hum Reprod Update. 2005;11:357–374. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmi013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ailhaud G, Grimaldi P, Negrel R. Cellular and molecular aspects of adipose tissue development. Annu Rev Nutr. 1992;12:207–233. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.12.070192.001231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexanderson C, Eriksson E, Stener-Victorin E, Lystig T, Gabrielsson B, Lonn M, Holmang A. Postnatal testosterone exposure results in insulin resistance, enlarged mesenteric adipocytes, and an atherogenic lipid profile in adult female rats: comparisons with estradiol and dihydrotestosterone. Endocrinology. 2007;148:5369–5376. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold AP, Gorski RA. Gonadal steroid induction of structural sex differences in the central nervous system. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1984;7:413–442. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.07.030184.002213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouret SG, Draper SJ, Simerly RB. Trophic action of leptin on hypothalamic neurons that regulate feeding. Science. 2004;304:108–110. doi: 10.1126/science.1095004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruns CM, Baum ST, Colman RJ, Eisner JR, Kemnitz JW, Weindruch R, Abbott DH. Insulin resistance and impaired insulin secretion in prenatally androgenized male rhesus monkeys. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:6218–6223. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chehab FF, Lim ME, Lu R. Correction of the sterility defect in homozygous obese female mice by treatment with the human recombinant leptin. Nat Genet. 1996;12:318–320. doi: 10.1038/ng0396-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Ahn KC, Gee NA, Ahmed MI, Duleba AJ, Zhao L, Gee SJ, Hammock BD, Lasley BL. Triclocarban enhances testosterone action: a new type of endocrine disruptor? Endocrinology. 2008;149:1173–1179. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbier P, Edwards DA, Roffi J. The neonatal testosterone surge: a comparative study. Arch Int Physiol Biochim Biophys. 1992;100:127–131. doi: 10.3109/13813459209035274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d'Anglemont de Tassigny X, Fagg LA, Dixon JP, Day K, Leitch HG, Hendrick AG, Zahn D, Franceschini I, Caraty A, Carlton MB, et al. Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism in mice lacking a functional Kiss1 gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:10714–10719. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704114104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donato J, Jr, Cravo RM, Frazao R, Gautron L, Scott MM, Lachey J, Castro IA, Margatho LO, Lee S, Lee C, et al. Leptin's effect on puberty in mice is relayed by the ventral premammillary nucleus and does not require signaling in Kiss1 neurons. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:355–368. doi: 10.1172/JCI45106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisner JR, Dumesic DA, Kemnitz JW, Colman RJ, Abbott DH. Increased adiposity in female rhesus monkeys exposed to androgen excess during early gestation. Obes Res. 2003;11:279–286. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan W, Yanase T, Nomura M, Okabe T, Goto K, Sato T, Kawano H, Kato S, Nawata H. Androgen receptor null male mice develop late-onset obesity caused by decreased energy expenditure and lipolytic activity but show normal insulin sensitivity with high adiponectin secretion. Diabetes. 2005;54:1000–1008. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.4.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferron M, Hinoi E, Karsenty G, Ducy P. Osteocalcin differentially regulates beta cell and adipocyte gene expression and affects the development of metabolic diseases in wild-type mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:5266–5270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711119105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferron M, Wei J, Yoshizawa T, Ducy P, Karsenty G. An ELISA-based method to quantify osteocalcin carboxylation in mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;397:691–696. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gay VL, Midgley AR, Jr, Niswender GD. Patterns of gonadotrophin secretion associated with ovulation. Fed Proc. 1970;29:1880–1887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gesta S, Tseng YH, Kahn CR. Developmental origin of fat: tracking obesity to its source. Cell. 2007;131:242–256. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haavisto AM, Pettersson K, Bergendahl M, Perheentupa A, Roser JF, Huhtaniemi I. A supersensitive immunofluorometric assay for rat luteinizing hormone. Endocrinology. 1993;132:1687–1691. doi: 10.1210/endo.132.4.8462469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotchkiss AK, Furr J, Makynen EA, Ankley GT, Gray LE., Jr In utero exposure to the environmental androgen trenbolone masculinizes female Sprague-Dawley rats. Toxicol Lett. 2007;174:31–41. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingalls AM, Dickie MM, Snell GD. Obese, a new mutation in the house mouse. J Hered. 1950;41:317–318. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a106073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman AS, Gottsch ML, Roa J, Byquist AC, Crown A, Clifton DK, Hoffman GE, Steiner RA, Tena-Sempere M. Sexual differentiation of Kiss1 gene expression in the brain of the rat. Endocrinology. 2007;148:1774–1783. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koutcherov Y, Mai JK, Ashwell KW, Paxinos G. Organization of human hypothalamus in fetal development. J Comp Neurol. 2002;446:301–324. doi: 10.1002/cne.10175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee NK, Sowa H, Hinoi E, Ferron M, Ahn JD, Confavreux C, Dacquin R, Mee PJ, McKee MD, Jung DY, et al. Endocrine regulation of energy metabolism by the skeleton. Cell. 2007;130:456–469. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis GW, Greenwald-Yarnell M, Phillips R, Coolen LM, Lehman MN, Myers MG., Jr Molecular mapping of the neural pathways linking leptin to the neuroendocrine reproductive axis. Endocrinology. 2011;152:2302–2310. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-0096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLusky NJ, Naftolin F. Sexual differentiation of the central nervous system. Science. 1981;211:1294–1302. doi: 10.1126/science.6163211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JA, Jordan CL, Breedlove SM. Sexual differentiation of the vertebrate nervous system. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:1034–1039. doi: 10.1038/nn1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro VM, Tena-Sempere M. Neuroendocrine control by kisspeptins: role in metabolic regulation of fertility. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2012;8:40–53. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2011.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negri-Cesi P, Colciago A, Pravettoni A, Casati L, Conti L, Celotti F. Sexual differentiation of the rodent hypothalamus: hormonal and environmental influences. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;109:294–299. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson C, Niklasson M, Eriksson E, Bjorntorp P, Holmang A. Imprinting of female offspring with testosterone results in insulin resistance and changes in body fat distribution at adult age in rats. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:74–78. doi: 10.1172/JCI1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nohara K, Zhang Y, Waraich RS, Laque A, Tiano JP, Tong J, Munzberg H, Mauvais-Jarvis F. Early-life exposure to testosterone programs the hypothalamic melanocortin system. Endocrinology. 2011;152:1661–1669. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nohara KW RS, Liu S, Ferron M, Waget A, Meyers M, Karsenty G, Burcelin R, Mauvais-Jarvis F. Developmental androgen excess programs sympathetic tone and adipose tissue dysfunction and predisposes to a cardiometabolic syndrome in female mice. American Journal of Physiology: Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2013 doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00620.2012. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pineda R, Garcia-Galiano D, Roseweir A, Romero M, Sanchez-Garrido MA, Ruiz-Pino F, Morgan K, Pinilla L, Millar RP, Tena-Sempere M. Critical roles of kisspeptins in female puberty and preovulatory gonadotropin surges as revealed by a novel antagonist. Endocrinology. 2010;151:722–730. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rana K, Fam BC, Clarke MV, Pang TP, Zajac JD, Maclean HE. Increased adiposity in DNA binding-dependent androgen receptor knockout male mice associated with decreased voluntary activity and not insulin resistance. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011 doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00584.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recabarren SE, Rojas-Garcia PP, Recabarren MP, Alfaro VH, Smith R, Padmanabhan V, Sir-Petermann T. Prenatal testosterone excess reduces sperm count and motility. Endocrinology. 2008;149:6444–6448. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sam S, Coviello AD, Sung YA, Legro RS, Dunaif A. Metabolic phenotype in the brothers of women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1237–1241. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T, Matsumoto T, Yamada T, Watanabe T, Kawano H, Kato S. Late onset of obesity in male androgen receptor-deficient (AR KO) mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;300:167–171. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02774-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seminara SB, Messager S, Chatzidaki EE, Thresher RR, Acierno JS, Jr, Shagoury JK, Bo-Abbas Y, Kuohung W, Schwinof KM, Hendrick AG, et al. The GPR54 gene as a regulator of puberty. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1614–1627. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simerly RB. Wired for reproduction: organization and development of sexually dimorphic circuits in the mammalian forebrain. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2002;25:507–536. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.112701.142745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JT, Acohido BV, Clifton DK, Steiner RA. KiSS-1 neurones are direct targets for leptin in the ob/ob mouse. J Neuroendocrinol. 2006;18:298–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2006.01417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stavreva DA, George AA, Klausmeyer P, Varticovski L, Sack D, Voss TC, Schiltz RL, Blazer VS, Iwanowicz LR, Hager GL. Prevalent Glucocorticoid and Androgen Activity in US Water Sources. Sci Rep. 2012;2:937. doi: 10.1038/srep00937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tena-Sempere M. KiSS-1 and reproduction: focus on its role in the metabolic regulation of fertility. Neuroendocrinology. 2006;83:275–281. doi: 10.1159/000095549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weyer C, Funahashi T, Tanaka S, Hotta K, Matsuzawa Y, Pratley RE, Tataranni PA. Hypoadiponectinemia in obesity and type 2 diabetes: close association with insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:1930–1935. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.5.7463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf CJ, Hotchkiss A, Ostby JS, LeBlanc GA, Gray LE., Jr Effects of prenatal testosterone propionate on the sexual development of male and female rats: a dose-response study. Toxicol Sci. 2002;65:71–86. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/65.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu MV, Manoli DS, Fraser EJ, Coats JK, Tollkuhn J, Honda S, Harada N, Shah NM. Estrogen masculinizes neural pathways and sex-specific behaviors. Cell. 2009;139:61–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xita N, Tsatsoulis A. Review: fetal programming of polycystic ovary syndrome by androgen excess: evidence from experimental, clinical, and genetic association studies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:1660–1666. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xita N, Tsatsoulis A. Fetal origins of the metabolic syndrome. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1205:148–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yildiz BO, Yarali H, Oguz H, Bayraktar M. Glucose intolerance, insulin resistance, and hyperandrogenemia in first degree relatives of women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:2031–2036. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.