Abstract

Indole compounds, found in cruciferous vegetables, are potent anti-cancer agents. Studies with indole-3-carbinol (I3C) and its dimeric product, 3,3’-diindolylmethane (DIM) suggest that these compounds have the ability to deregulate multiple cellular signaling pathways, including PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. These natural compounds are also effective modulators of downstream transcription factor NF-κB signaling which might help explain their ability to inhibit invasion and angiogenesis, and the reversal of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) phenotype and drug resistance. Signaling through PI3K/Akt/mTOR and NF-κB pathway is increasingly being realized to play important role in EMT through the regulation of novel miRNAs which further validates the importance of this signaling network and its regulations by indole compounds. Here we will review the available literature on the modulation of PI3K/Akt/mTOR/NF-κB signaling by both parental I3C and DIM, as well as their analogs/derivatives, in an attempt to catalog their anticancer activity.

Keywords: Indole compounds, PI3K, cancer therapy, NF-κB, Glucosinolates

INTRODUCTION

Cancer is a major public health problem in the US as well as worldwide. In US, cancer-related deaths are second only to heart disease-related deaths. They account for close to a quarter of all deaths [1]. Chemotherapy remains an important tool to treat cancer patients, and a number of putative therapeutic agents are under evaluation for their possible role in cancer management. Towards this end, there has been a realization for few decades now, about the possible use of natural agents as cancer therapeutic agents. Accordingly, many naturally occurring compounds have been proposed as potential anticancer compounds, and their molecular mechanisms have been characterized [2]. The rationale for the use of natural compounds in cancer research is from the observation that these agents are relatively non-toxic and usually well-tolerated.

Natural chemical compounds found in fruits and vegetables are now known to possess anticancer properties and, moreover, data from epidemiological studies have shown that the consumption of fruits, soybean and vegetables is associated with reduced risk of several types of cancers [3,4]. Particularly, indole-3-carbinol (I3C) and its in vivo dimeric product 3,3′-diindolylmethane (DIM) are potent compounds with anticancer properties [5]. These compounds affect multiple signaling pathways leading to their observed biological effects, a phenomenon referred to as ‘pleiotropic activity’. A significant amount of information is available on the effect of indole compounds, I3C and DIM, on several distinct signaling pathways reported by many investigators, including our own publications [2,4–11]. In this article, we will review the applicability of these compounds for specific targeting of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) – protein kinase B (Akt) -mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway. Our own research investigations have identified Nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) pathway as a core central pathway that interacts with multiple upstream and downstream signaling pathways, including the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway, and plays an important role in invasion, angiogenesis and metastasis of human cancers in experimental models. Interestingly, a number of reports have documented an inhibition of NF-κB by indole compounds [5,12–14]. Therefore, it appears that PI3K/Akt/mTOR/NF-κB signaling is an attractive target for therapy in aggressive cancers. In this article, we summarize our current understanding of the mechanisms by which indole compounds, particularly I3C and DIM regulates PI3K/Akt/mTOR/NF-κB signaling in various human cancer models.

INDOLE COMPOUNDS

Indole compounds are natural compounds found in cruciferous vegetables such as broccoli, cauliflower, cabbage and brussels sprouts. All chemical compounds that contain an indole ring are called indoles. Indole, chemically, is an aromatic heterocyclic organic compound with a bicyclic structure, consisting of a six-membered ring fused to a five-membered nitrogen-containing pyrrole ring. A review of 206 epidemiological studies and 22 animal studies reported the beneficial effect of I3C against tumorigenesis [15]. Another study found that the consumption of cruciferous vegetables was strongly associated with reduced bladder cancer risk [16]. Cruciferous vegetables are excellent source of a number of phytochemicals, including indole derivatives, dithiolthiones, and isothiocyanates. Initially, indoles became economically important as dyestuffs (e.g., indigo). Likewise, vinca alkaloids (e.g., vincristin, vinblastin) which were first isolated from Catharanthus roseus (Madagascar periwinkle) belong to the anticancer active agents known longest for their tubulin targeting properties [17]. Staurosporin, isolated from Streptomyces staurosporeus, served as a lead compound and blueprint for the development of kinase inhibitors. Its refinement led to promising drug candidates such as sunitinib and enzastaurin which are currently undergoing advanced clinical trials against cancer [18–20]. The duocarmycins feature DNA-targeting 5,6,7-trimethoxy-indole moieties connected to alkylating spirocyclopropylhexadienones which binds to the minor groove of DNA via sequence-selective N3-adenine alkylation. The two well-studied indoles with anticancer properties are I3C and its dimer, DIM [5,13] and we will focus our discussion on these two compounds documenting the existing literature on their effects on PI3K/Akt/mTOR/NF-κB signaling.

I3C

I3C has been found in fruits and vegetables, including members of the cruciferous family and, particularly, members of the genus Brassica. Its anticancer effects in experimental animals [21–24] and humans [25,26] have led to its use as a possible chemopreventive agent [27]. In cruciferous vegetables, I3C is derived from the hydrolysis of glucobrassicin, a glucosinolate. Glucosinolates are water-soluble compounds derived from glucose and an amino acid; they contain a central carbon atom which is bound via a sulfur atom to the thioglucose group and via a nitrogen atom to a sulfate group. The central carbon is also bound to a side group, and the variation in the side group is responsible for the variation in the biological activities of compounds. Glucosinolates with an indole side chain is responsible in forming indoles. The stability of glucosinolates is strongly influenced by the presence of external factors, and, therefore, the amount of I3C formed in foods is variable, and depends on the processing and preparation of those foods. I3C is synthesized from indole-3-glucosinolate by the action of enzyme myrosinase [28]. The amount of I3C found in the diet can vary greatly, ranging from 20 and 120 mg daily, and is dependent on dietary intake of cruciferous vegetables and their variable concentrations [29].

It is documented that populations which consume higher amounts of cruciferous vegetables have lower incidence of cancer or improved biochemical parameters, such as decreased oxidative stress, compared to controls [30–32]. The National Research Council, Committee on Diet, Nutrition, and Cancer has recommended increased consumption of cruciferous vegetables as means to reduce cancer incidence. Epidemiological findings have shown that consumption of cruciferous vegetables protects against cancer more effectively than the total intake of fruits and vegetables [33], and this effect of cruciferous vegetable is attributed to the presence of I3C [24–26,34]. The beneficial anticancer effects of I3C were first recognized by ‘Cato the Elder’, a Roman statesman (234-149 BC) who said - "If a cancerous ulcer appears upon the breast, apply a crushed cabbage leaf, and it will make it well" [5].

DIM, THE DIMERIC PRODUCT OF I3C

Although I3C is an effective anticancer agent, it suffers from being highly unstable. Under the acidic environment of the stomach, I3C molecules can combine among each other to form a complex mixture of biologically active compounds, the acid condensation products [35]. The most prominent acid condensation product of I3C is the dimer DIM. DIM accounts for only 10–20% of the products of I3C and, therefore, a daily ingestion of I3C from the diet will typically provide between 2 and 24 mg of DIM. Formation of DIM from I3C is believed to be the likely prerequisite for I3C-induced anti-carcinogenesis because DIM is the most potent product of I3C [36].

PI3K/Akt/mTOR SIGNALING AS POTENTIAL TARGET IN CANCER RESEARCH

The PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway is a cascade of events that plays a key role in the broad variety of physiological and pathological processes. PI3K pathway has been implicated in cancer ever since its discovery as viral oncoproteins-associated enzymatic activity [37]. With the emergence of data during the last decade, it has been realized that PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway is one of the most frequently targeted pathways in all sporadic human cancers, and it has been estimated that mutations in the individual component of this pathway account for as much as 30% of all known human cancers [37,38]. PI3K is activated by receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) or Ras and activated PI3K, in turn, activates several intracellular signaling molecules with Akt being its most preferred downstream target. Akt activates an array of substrates through phosphorylation, and the factors that are downstream of Akt regulate four broad processes - cell survival, cell-cycle progression, cell growth and cell metabolism [37]. A number of physiological events involve signaling through Akt, and it remains one of the most-studied molecule in the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. The mTOR is an important molecule downstream of Akt, and is activated when Akt abrogates the suppressive action of tumor suppressor tuberin (also known as tuberous sclerosis complex 1, TSC1) on mTOR [37,39].

Once activated, the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway plays a crucial role in the cell growth and metabolism ultimately influencing the invasion, metastasis and aggressiveness of cancer cells. This provides a direct rationale in support of targeting this pathway as novel therapeutic option for better prognosis in cancer patients [40–42]. As mentioned above, the fact that this signaling pathway is involved in more than a quarter of known cancers further supports that targeting this pathway would be important for cancer cure. In addition to the contribution of this pathway to primary cancer progression, its role in resistance to targeted therapy is also being realized [43]. This gives one more reason for the therapeutic targeting of this signaling pathway.

THE ASSOCIATION BETWEEN NF-κB AND PI3K/Akt/ mTOR SIGNALING

NF-κB is a central signaling factor involved in the development and progression of human cancers as well as in the acquisition of drug-resistant phenotype in highly aggressive malignancies [2,14,44–49]. NF-κB pathway includes several important molecules such as NF-κB, IκB, IKK, etc.; however, NF-κB is the key protein that has been documented as a major culprit and the critical target for therapy in human cancers [2,46,50]. There is evidence to support a crosstalk between PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway and NF-κB [51–54]. NF-κB is not a molecule within the core PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway, but it is downstream of Akt. Activation through Akt is important for many tumorigenic functions of NF-κB. Since, both mTOR and NF-κB are downstream effector Akt, it appears that the signaling through Akt can potentially proceed in two mutually exclusive independent directions, either through mTOR or through NF-κB. However, this is not always the case and there seems to be a crosstalk between mTOR and NF-κB [55]. Firstly, mTOR is known to regulate Akt via a feedback mechanism, and this can help in the regulation of NF-κB by mTOR through regulation of Akt via the mTOR-associated protein raptor. Secondly, there seems to be a more direct regulation of NF-κB by mTOR which involves IKK. In the activation of NF-κB, IKK plays an important role by phosphorylating the inhibitory IκBα leading to its dissociation from NF-κB, resulting in an activated NF-κB that translocates to nucleus. The mTOR mediated induction of IKK leads to to the activation of NF-κB [55]. Based on these observations, it is quite clear that despite being not considered a member of PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling, because of its role in other signaling pathways as well, NF-κB maintains a vibrant crosstalk with PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. NF-κB happens to be an important target of indole compounds and, therefore, in this review we will point out modulation of NF-κB by indoles while discussing the regulation of PI3K/Akt/mTOR. In summary, we will use the phrase PI3K/Akt/mTOR/NF-κB signaling throughout this article.

INHIBITION OF PI3K/Akt/mTOR/ NF-κB SIGNALING BY I3C

In one of the earliest reports on the subject, we reported a modulation of PI3K-Akt signaling by I3C in prostate cancer cells [56]. I3C not only inhibited the phosphorylation and activation of Akt directly but also abrogated epidermal growth factor (EGF)-induced activation of PC3 prostate cancer cells. Even the PI3K activation by EGF was found to be inhibited by I3C. Soon after, we extended our studies to investigate the mechanism of action of I3C against breast cancer cells. We observed a cancer-specific action of I3C because it only affected the MCF-10A-derived malignant cells but spared the parental MCF-10A non-tumorigenic cells [57]. Mechanistically, we found similar results as in prostate cancer cells as reported above i.e. I3C abrogated the EGF-induced activation of Akt. In this study, we also examined a connection between Akt and NF-κB and reported an induction of NF-κB by ectopic expression of Akt. This is in line with the available literature and established a crosstalk between Akt and NF-κB in our experimental model. As expected, treatment with I3C also abrogated the EGF-induced activation of NF-κB.

In another report on the activity of I3C against Akt-NF-κB signaling, this time in lung cancer model, I3C was reported to significantly inhibit vinyl carbamate-induced lung adenocarcinoma in mice [58]. I3C, at a dose of 70 micromol/g in diet, resulted in a significantly less tumors in the lung. The incidence, multiplicity as well as size of tumors were reduced in I3C-administered mice. Analyses of tumor tissues revealed an inhibition of activated Akt as well as NF-κB in I3C treated mice. The authors also noticed inhibition of IKBα degradation by I3C. This might explain the inhibition of NF-κB activation. As discussed above, IKBα associates with NF-κB and inhibits its activity by retaining it in the cytoplasm. Due to the inhibition of the degradation of IKBα, I3C clearly showed that one of the important effects of I3C is mediated through the inactivation of NF-κB. In a follow up study [59], this research group reported an anti-carcinogenic effect of I3C against 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone plus benzo[a]pyrene-induced lung tumors in mice. I3C treatment resulted in reduced number of lung tumors per mouse (8.4±1.5), compared to control mice (13.0±4.1). Cigarette smoke condensate treatment was used to study the mechanism in vitro in HBEC and A549 lung cancer cells. Again, a marked inhibition of Akt as well as NF-κB was observed in I3C-treated cells. These mechanistic studies also supported the earlier in vivo study conducted by these authors [60] where I3C was shown to inhibit Akt, resulting in the inhibition of carcinogen-induced lung tumors.

The results from these studies demonstrated an in vivo anticancer action of I3C against experimental lung cancer model; however, some toxicity was observed especially at the high dose of I3C which also happened to be the most effective dose [58,60]. To address this, the authors combined I3C with silibinin in a later study [61]. This was done with reduced doses of I3C. In in vitro assays in A549 and H460 lung cancer cells, a significant inhibition of Akt and induction of apoptosis was observed in the cells treated with combination. The doses chosen were so low that the single agent treatment had no effect. In vivo, the authors observed a significantly enhanced anticancer activity against the carcinogen-induced lung tumors, and the multiplicities of tumors on the surface of the lung and adenocarcinoma were reduced by 60 and 95%, respectively. Taken together, the research investigations of this team have indicated an anticancer activity of I3C against carcinogen-induced lung cancer, and the key signaling pathway modulated by I3C was the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway [62].

In a study that combined I3C with another natural compound, genistein (obtained from soy) [63], the combination of these two anticancer agents was found to be more effective in the inhibition of Akt, resulting in increased induction of apoptosis in HT-29 colon cancer cells. In addition to Akt, this work also looked at the effect on mTOR. It was observed that the combinational treatment resulted in enhanced autophagy, an event that was mediated by inactivation of mTOR. This study indicates a dual effect of I3C, in combination with genistein, in cancer cells – induction of apoptosis through inhibition of Akt and induction of autophagy through inhibition of mTOR. Collectively, apoptosis and autophagy result in significantly reduced cell growth of cancer cells.

In addition to the observed in vivo toxicity, as discussed above, I3C also has a poor metabolic profile and this led Chao et al. to develop novel class of indole analogs in an attempt to optimize and perhaps enhance I3C’s anticancer properties [64]. The computer-aided rational drug design resulted in generation of these analogs. When tested, one of the analog, SR13668, stood out as the most promising analog which was associated with minimal toxicity, and the most potent oral anticancer activity. Interestingly, this group used the blockage of EGF-activated Akt activation as the criteria to screen potential analogs, a concept that was successfully demonstrated in our laboratory, with regards to efficacy of I3C (discussed above). Evaluation of OSU-A9, an I3C derivative [65], in multiple oral squamous cell carcinoma cells revealed significantly improved anticancer activity of this derivative, of the order of two-orders-of-magnitude, compared to I3C. This new derivative was also found to inhibit Akt and NF-κB signaling pathways, thus preserving the mechanism of action of the parent compound.

Studies with a cyclic tetrameric derivative of I3C – CTet, formulated in γ-cyclodextrin [66], in breast cancer MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells, showed cell cycle arrest. It was found that the derivative predominantly induced autophagy, as opposed to apoptosis, in both the cell lines and inhibition of Akt was identified as the key step in such activity of CTet. The compound was also found to be active in vivo with no apparent toxicity. In yet another study aimed at synthesizing a more potent antitumor derivative of I3C [67], the (3-chloroacetyl)-indole (3CAI) derivative was observed to be much more effective than I3C in its activity against colon cancer cells. This derivative was characterized to be a very specific inhibitor of Akt which further underlines the importance of Akt in mediating the anticancer action of I3C. 3CAI-induced inhibition of Akt was also observed to result in the inhibition of downstream mTOR, thus signifying an effective inhibition of PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway by I3C-related indole compounds.

I3C has been studied for its ability to prevent H2O2-induced inhibition of gap junctional intercellular communication (GJIC) [68]. GJIC is involved in regulating cell proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis, and the inhibition of its induction by I3C is a surrogate proof for the ability of I3C to inhibit all the GJIC-mediated cellular events. It was observed that the prevention of GJIC by I3C depends upon the inactivation of Akt. An effect similar to I3C action was observed when an inhibitor of PI3K, LY294002, was tested. These results are indicative of an effect of I3C on PI3K-Akt signaling leading to reduced proliferation and growth of cancer cells.

INHIBITION OF PI3K/Akt/mTOR/NF-κB SIGNALING BY DIM

Similar to I3C, our laboratory was the first to report an anticancer action of DIM as well. In a study involving prostate cancer PC3 cells [69], we observed a cancer cell-specific activity of DIM where it induced apoptosis selectively in cancer cells but not in the non-tumorigenic CRL2221 cells. DIM activity was found to be mediated by its inhibition of PI3K as well as Akt in the cancer cells. In addition to endogenous PI3K activity, DIM also inhibited EGF-induced PI3K activity. Further, we established a cross talk between NF-κB and Akt; however, this was effectively attenuated by DIM. In a parallel study in breast cancer cells [70], we established a similar cross talk between NF-κB and Akt in malignant MCF-10A-derived cells. DIM not only inhibited the activation of Akt and NF-κB, it was found to modulate multiple steps in NF-κB signaling. DIM inhibited the phosphorylation of IKBα, thus inducing the inhibitory complex of NF-κB. It also blocked the translocation of NF-κB to the nucleus. These studies provided compelling preliminary data in support of an effective inhibition of PI3K/Akt/mTOR/NF-κB signaling pathway by DIM.

DIM is a natural dimer of I3C and in a preliminary study comparing these two indoles, Garikapaty et al. observed that DIM is a better anti-proliferative agent than I3C with significantly reduced IC50 against androgen dependent [71] as well as androgen independent [72] prostate cancer cells. In both of these studies, DIM was found to inhibit activation of PI3K as well as Akt. Our own investigations [73] in hormone-responsive and hormone-nonresponsive prostate cancer cells confirmed the inhibition of Akt by DIM and the inhibition of Akt-NF-κB crosstalk. The results were confirmed in vivo in an experimental prostate cancer bone metastasis model. This study also revealed a down-regulation of androgen receptor by DIM, an event which was later found to be mediated studies and all subsequent studies, we have used BR-DIM, a formulated DIM with significantly enhanced bioavailability.

As a mechanism of induction of apoptosis by DIM in breast cancer cells, we observed an induction of cell cycle inhibitor p27 in DIM-treated BT-20 and BT-474 cells [74]. As expected, an inhibition of Akt was observed; however, this was preceded by induction of p27. These observations shed new light on the mechanism of action of DIM, suggesting a complex regulation of Akt and cell cycle by DIM leading to its anticancer effects. In a study that documented a direct inhibition of mTOR by DIM [75], we performed experiments in platelet-derived growth factor-D (PDGF-D)-over-expressing prostate cancer PC3 cells and observed an inhibitory action of DIM against these highly invasive cells. DIM was found to inhibit Akt and mTOR in these cells, resulting in significantly reduced cell invasion and angiogenesis. Although rapamycin is a known suppressor of mTOR, our studies revealed that DIM is a better therapeutic agent. This was based on the finding that inhibition of mTOR by rapamycin led to an activation of Akt via reverse feedback from suppressed mTOR. Such activated Akt has the potential to drive cancer cell growth and invasion through alternate pathways, such as NF-κB as discussed above, which can negate the cellular effects of the inhibitory activity of mTOR alone. DIM, by virtue of its ability to inhibit both Akt and mTOR, turned out to be a better therapeutic agent in these highly metastatic cells. These results supports the use of pleiotropic agents such as indoles in anticancer research.

Inhibition of Akt by DIM has been shown to inhibit migration and invasion of multiple cancer cells [76,77]. Such activity has also been reported in cholangiocarcinoma [78], leukemia [79] and cervical cancer [80] cells. Recently, in oral squamous cell carcinoma cells, DIM was able to induce cell cycle arrest and apoptosis through an action on Akt and NF-κB [81]. Regulation of Akt by DIM was recognized by the authors to result in several downstream events showing the activated pro-apoptotic molecules. It has also been shown that DIM’s inhibition of angiogenesis was more pronounced than I3C and that DIM was a better Akt inhibitor than its parent compound [82].

The NF-κB-Akt inhibitory activity of DIM is also believed to be important for its chemo-sensitization ability where it sensitizes cancer cells to the cytotoxic effects of therapeutic drugs [83]. Such chemo-sensitization ability of DIM has been reported in breast cancer cells where it sensitized the cells to taxotere treatment [84] through significantly reduced NF-κB and Akt. Ichite et al. delivered a derivative of DIM, 1,1-bis(3’-indolyl)-1-(p-biphenyl) methane, to mice via inhalation alone and in combination with docetaxel, and reported a combined inhibitory effect on Akt as well as NF-κB expression [85]. Based on these reports it is safe to conclude that DIM’s anticancer and chemosensitizing properties are dependent on the modulation of PI3K/Akt/mTOR/NF-κB pathway [86].

DERIVATIVES AND ANALOGUES OF INDOLE-3-CARBINOL

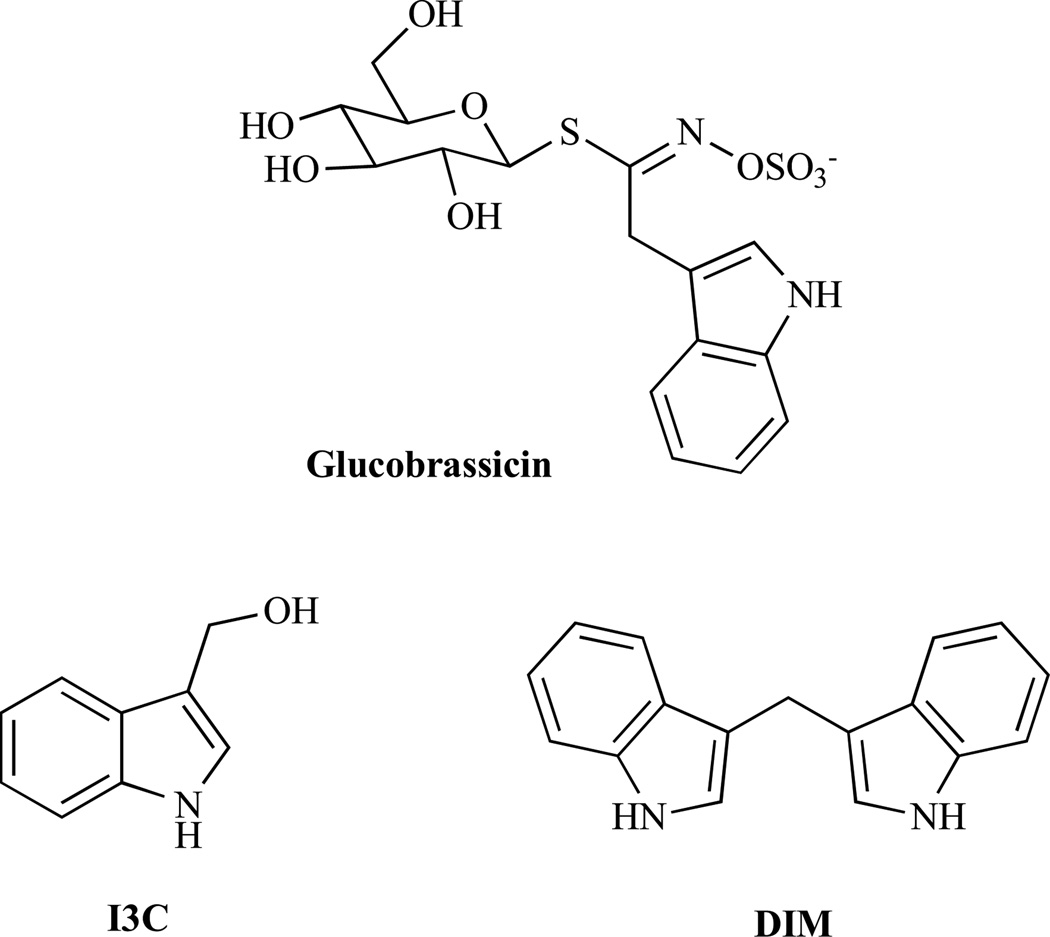

Simple naturally occurring indoles like glucobrassicin and its metabolite I3C (Fig. 1) are often associated with vegetables of the Brassica genus, for instance, broccoli, cabbage, and sprouts. Glucobrassicin is also found in high concentrations in woad (Isatis tinctoria, also known as German Indigo), a plant that has been used for tattoos/body painting and for dyeing cloth by Western and Central European people from ancient times (Celts) until the late Middle Ages. After consumption of Brassica vegetables, the I3C is converted to the dimer 3,3’-diindolylmethane (DIM) in the acidic environment of the stomach. These indole derivatives exert pleiotropic anticancer activities by inducing apoptosis and modulating various signalling pathways [5].

Fig. (1).

Structures of glucobrassicin, I3C and DIM.

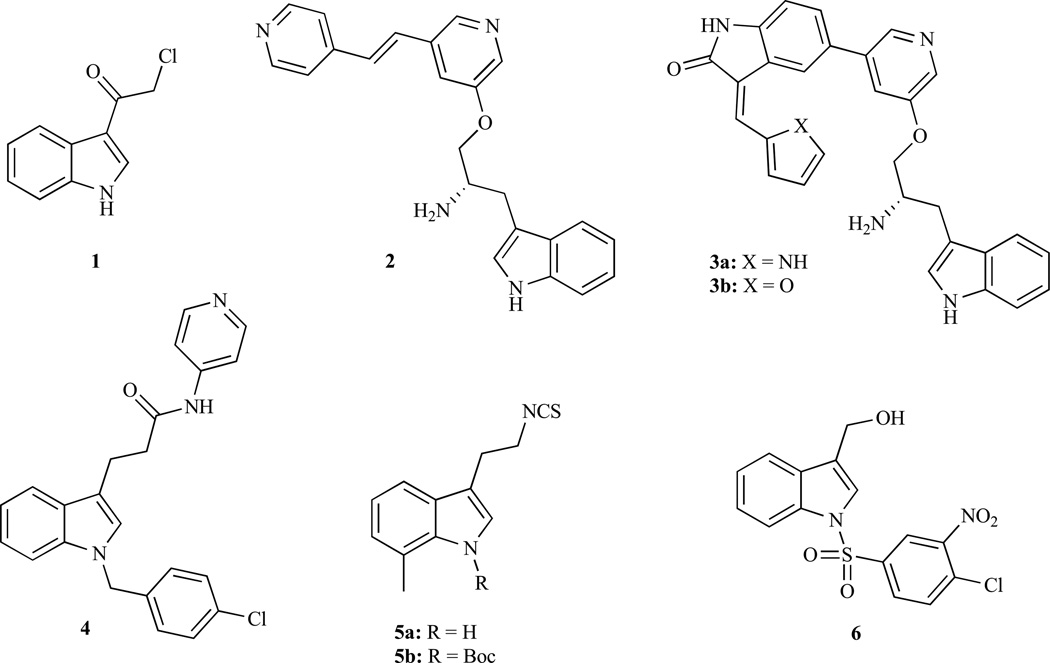

3-Chloroacetylindole (1, Fig. 2) features a simple and easily available I3C congener which can be prepared via the reaction of indole with 2-chloroacetyl chloride in the presence of pyridine [87]. Compound 1 revealed stronger HCT-116 colon cancer cell growth inhibition (IC50 < 4 µM) compared with I3C (IC50 > 200 µM) [67]. Screening on 85 kinases showed selective AKT1 inhibition by 1 (1 µM), as well as AKT2 inhibition at 4 µM. Docking studies on the binding mechanism of 1 revealed one hydrogen bond with Glu17 and a configuration parallel to Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 in the AKT1 PH domain, and three hydrogen bonds with Lys14, Leu52, Arg86 and a configuration perpendicular to Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 in the AKT2 PH domain. In vitro pull-down assays with 1 showed a direct binding in an ATP non-competitive manner, thus, 1 does not bind to the ATP binding site but to an AKT allosteric site. Indole 1 also inhibited AKT-mediated mTOR phosphorylation in a time dependent manner as well as the anti-apoptotic factor Bcl-2 and AKT-dependent phosphorylation of ASK1, while pro-apoptotic proteins like p53 and p21 were up-regulated. All these effects likely contribute to the efficient apoptosis induction in HCT-116 and HT-29 colon cancer cells by 1. In addition, orally administered 1 (30 mg/kg) inhibited the growth of HCT-116 mouse xenografts up to 50% compared with the control group. Investigations (immunohistochemistry and H&E staining) of the tumor treated with 1 revealed a suppression of AKT-mediated phosphorylation of mTOR and GSK3β A group of the Abbott Laboratories disclosed the preparation and biological activity of a bispyridinylethylene modified indole 2 which showed strong AKT1 inhibition (IC50 = 14 nM) [88]. In addition, 2 revealed moderate cytotoxic activity in prolymphocytic FL5.12-Akt1 cells (IC50 = 3 µM) which overexpress AKT1, and in MiaPaCa-2 human pancreas cancer cells (IC50 = 12 µM). The X-ray structure of 2 in a complex with the active site of PKA, a closely related protein kinase, was determined and revealed the binding of the terminal pyridine to the backbone NH of Val123 in the hinge region in the ATP-binding site, while the central pyridine interacts with Lys72. The amino group is located in the Mg-binding loop via ionic interactions, while the indole fragment lies below the glycine-rich loop. Additionally, indole 2 revealed favourable oral bioavailability in four different species (mouse, rat, dog, and monkey). Hence, further investigations to optimize this compound are warranted. The same group investigated a series of oxindole-pyridine substituted inhibitors (3a, 3b) [89]. While 3b was highly selective towards AKT1 (IC50 = 1 nM), 3a also significantly inhibited AKT2 (IC50 = 5 nM), PKA (IC50 = 2 nM), CDK1 (IC50 = 4 nM), and SRC (IC50 = 15 nM) as well as AKT 1 (IC50 = 1 nM). The observed multiple-kinase inhibition might be the reason for the stronger cytotoxic activity of 3a in FL5.12-Akt cells (IC50 = 0.20 µM) and MiaCaPa-2 cells (IC50 = 0.14 µM) compared with the AKT1-specific 3b (IC50 = 0.40 µM and 0.88 µM, respectively) compound. The higher activity of 3a was also observed in MiaCaPa-2 mouse xenografts at doses of 25 mg/kg per day (T/C = 13% at day 15).

Fig. (2).

Structures of I3C analogues with AKT-modulatory activity.

The I3C-related N-benzyl compound oncrasin-1 as well as its congeners showed excellent and selective activity against K-ras mutated lung cancer cells, presumably due to the inhibition of RNA polymerase II [90,91]. Lang and co-workers recently developed the oncrasin congener AD412 as an immunosuppressant agent (4) [92]. Indole compound 4 functions as a JAK3 inhibitor and suppresses JAK3-mediated AKT phosphorylation at Ser473, which is crucial for AKT activation, in IL-2 stimulated CTL-L2 cells at doses of 90 µM.

Brard and co-workers investigated a new indole ethyl isothiocyanate 5a [93]. This compound (3 µM) down-regulated AKT in SMS-KCNR neuroblastoma cells besides its role in the activation of pro-apoptotic p38 and SAP/JNK. In addition, it showed significant growth inhibitory activity (IC50 = 2.5–5.0 µM) in a panel of four neuroblastoma cell lines (SMS-KCNR, SK-N-SH, SH-SY5Y, and IMR-32). On the basis of 5a compound, the same group developed indole 5b (NB7M) and investigated its effects on ovarian cancers and neuroblastoma [94,95]. Compound 5b exhibited higher cytotoxic activity (IC50 = 1.0–2.0 µM) than 5a in the above mentioned four neuroblastoma cell lines, and down-regulated the pro-survival factors AKT and PI-3K in SMS-KCNR and SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells at a concentration of 1.5 µM [18]. Therefore further clinical investigation of 5b is warranted especially because of the fact that neuroblastoma mainly affects little children and there is not optimal treatment.

Chen and co-workers disclosed another I3C congener with potent anticancer activity, OSU-A9 (6). Initial investigations in prostate cancer showed high degree of similarity between I3C and 6 concerning the mode of action; however, at a much lower concentration [96]. For instance, the phosphorylation of AKT was suppresses by 6 at 2 µM compared with I3C at 200 µM in PC-3 prostate cancer cells. In line with this results, indole 6 showed significant tumor-selective growth inhibitory activity both in androgen-nonresponsive PC-3 (IC50 = 2.0 µM) and in androgen-responsive LNCaP (IC50 = 3.8 µM) prostate cancer cells which was two orders of magnitude higher than for I3C. PC-3 xenograft tumors treated with 6 (25 mg/kg, i.p.) for 42 days led to 85% tumor growth suppression, and Western Blot investigations of the tumor remnant revealed strong reduction of phosphorylated AKT. Hence, 6 might be a suitable candidate for further clinical development for prostate cancer therapy. Similar promising results were obtained from breast cancer (70% growth suppression in MCF-7 breast cancer xenografts using 50 mg/kg dose of the compound 6 given orally) and hepatoma (80% growth suppression in Hep3B hepatoma xenografts using 50 mg/kg) without apparent toxicities [97,98].

The naturally occurring lactone wortmannin showed strong mTOR inhibition (IC50 = 40 nM) [99]. Yang and his team disclosed an α-methylene-γ-lactone modified indole 7 (S9, Fig. 3) featuring a combination of wortmannin and I3C, which inhibited AKT and mTOR phosphorylation at 50 µM dose as documented by Western blot analyses of Rh30 rhabdomyosarcoma cells [100]. A more recent study on indole 7 disclosed similar activity in ovarian cancer cells [101]. In addition to the inhibition of AKT-mTOR signalling, 7 also showed binding to the colchicine-binding site of tubulin due to the MOM group leading to G2/M phase arrest of the cell cycle in SK-OV-3 ovarian cancer cells. A direct binding to the ATP binding sites of PI-3K and mTOR has been documented by docking studies showed hydrogen bonding of 7 with Tyr836 and hydrophobic interactions with Trp780, Ile800/848/850 and Val851 of the PI-3K, as well as hydrogen bonding with Thr2245, Lys2187 and His2447 residues of mTOR. In addition, indole 7 exhibited distinct tumor growth inhibition in Rh30 rhabdomyosarcoma (T/C = 0.56) and SMMC7721 hepatoma (T/C = 0.52) xenograft models when administered i.p. (50 mg/kg). 7-Nitroindole compound 8 is another potent AKT inhibitor [102]. Though being developed as a competitive inhibitor of the ATP-binding site of Chk2, indole 8 also inhibits mutant AKT1(S473D) at a low concentration (IC50 = 10.9 nM) and revealed synergistic effects together with topotecan, camptothecin and radiation, while protecting mouse thymocytes from radiation damage. Finlay and co-workers have recently disclosed an indole modified sulfonylmorpholinopyrimidine compound 9 [103]. Indole 9 exhibited selective mTOR inhibiton (IC50 0.288 µM). Docking results proposed a hydrogen bond between the indole NH and a glutamate residue (E2190) of mTOR. However, due to the low bioavailability of 9 further investigations on this interesting compound class are needed in order to develop a suitable drug candidate against mTOR related diseases. Ferlin, et al. developed a fused indole (pyrroloquinolinone) derivative 10 (MG-2477) featuring a tubulin inhibitor which also suppressed the AKT/mTOR pathway in A549 lung cancer cells [104]. Indole 10 induced autophagy (LC3 shift) via AKT inhibition and reduced phosphorylation of mTOR downstream targets p70 ribosomal S6 kinase and 4E-BP1. In addition, 10 showed strong cytotoxic activity both in A549 lung cancer cells (IC50 = 20 nM) and in the taxol-resistant sublines A549-T12 (IC50 = 20 nM) and A549-T24 (IC50 = 20 nM) cells as well as in a panel of 12 different cancer cell lines [105].

Fig. (3).

Structures of indole derivatives with AKT/mTOR-modulatory activity.

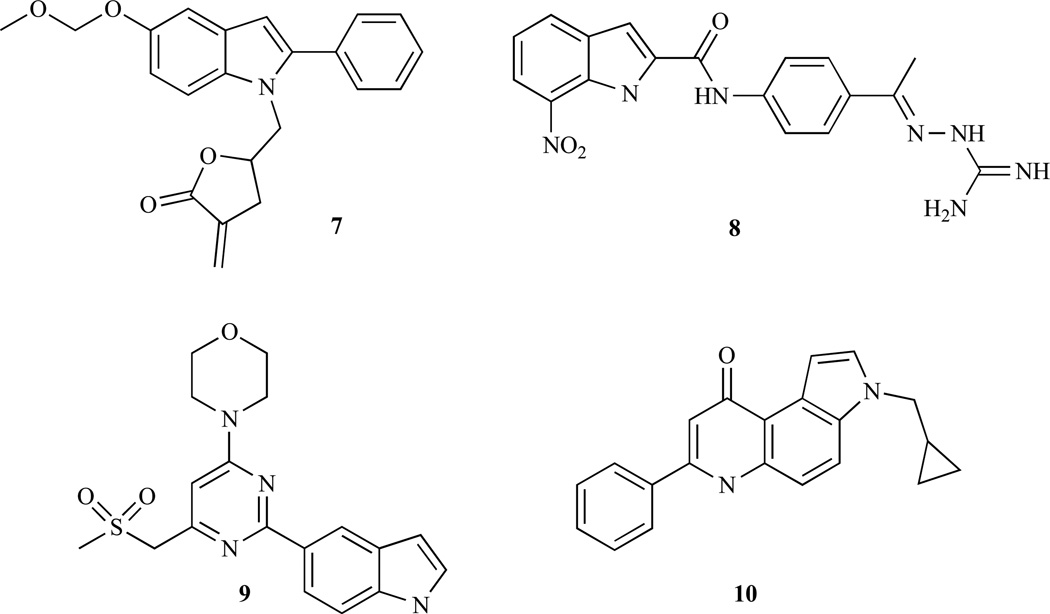

DERIVATIVES AND ANALOGUES OF DIM

The design and preparation of new DIM analogues would likely lead to promising anticancer agents. Consistent with this promose, a potent fused DIM analogue 11 was reported by Jong, et al. (Fig. 4) [64]. It turned out to be highly cytotoxic against MCF-7 breast cancer cells (IC50 = 0.19 µM), it blocked AKT activation (phosphorylation) and showed a distinct in vivo growth inhibition of MDA-MB-231 xenografts when administered orally (10 mg/kg/day). Hence, compound 11 is a suitable candidate for further clinical development. Safe and co-workers disclosed DIM analogues which are aryl-substituted at the methylene-bridge. Compounds 12a and 12b exhibited significant growth inhibitory activity against SW480 colon cancer cells (IC50 < 10 µM), and activated PPARγ [106]. Interestingly, these compounds (5 µM) induced and enhanced AKT phosphorylation and its activation in SW840 cells. Despite its close relation to DIM, the anticancer active derivatives 12a and 12b obviously possess a different mode of action. In addition, orally administered 12b inhibited SW480 xenografts at doses of 20 mg/kg and significantly induced caspase-3 and pro-apoptotic NAG-1 (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug activated gene 1) in the tumor remnants. Brandi, et al. investigated the effects of the macrocyclic 2,3-diindolyl tetramer 13 on breast cancer xenografts (Fig. 4) [66]. For this purpose 13 was formulated with γ-cyclodextrin. This formulation of 13 showed distinct in vitro activity against estrogen responsive MCF-7 and triple-negative MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells (IC50= 1.2 µM and 1.0 µM, respectively). In vivo, formulations of compound 13 blocked tumor growth in MCF-7 xenografts (5mg/kg/day) and even led to a slight tumor regression. In addition, 13 inhibited both AKT activation and increased p21 levels, and induced autophagy in breast cancer cells. All these results suggest that further clinical investigations of this hopeful drug candidate is warranted. In 1994, a Japanese group isolated interesting bis-indoles, leptosine A–F from the marine fungus Leptoshaeria sp., a fungus which was initially isolated from the marine alga Sargassum tortile collected in the Tanabe Bay of Japan [107]. Compound 14 (leptosine F) and its congener leptosine C exhibited highly cytotoxic activity against RPMI8402 lymphoblastoma cells (IC50 = 8.2 nM for 14, IC50 = 0.62 nM for leptosine C), inhibited topoisomerases I and II, and led to G1/S cell cycle arrest [108]. The AKT pathway was also found to be suppressed in HEK293 human embryonic kidney cells due to dephosphorylation of AKT (Ser473) leading to caspase-3 activation and apoptosis. The naturally occurring bisindole staurosporine is a potent multi-kinase inhibitor operating by competitive binding to the ATP-binding site of various kinases [109]. However, the multitude of potential targets that staurosporine can interact with has prevented its clinical application. Another derivative 15 (MKC-1), which affects microtubules, importin-β and the AKT/mTOR pathway, led to responses in patients suffering from breast cancer [110]. The suppression of AKT/mTOR signalling by 15 presumably occurs via inhibition of the mTOR/rictor pathway.

Fig. (4).

Structures of DIM analogues with AKT/mTOR-modulatory activity.

An AstraZeneca research group recently disclosed the active indole-based pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidines 16a and 16b (Fig. 5) [111]. Though developed for targeting CK2 kinase, both compounds also revealed strong inhibition of AKT phosphorylation (IC50 = 34 nM for 16a, 27 nM for 16b). Compound 16b also exhibited significant growth inhibitory activity against HCT-116 colon cancer cells (IC50 = 0.7 µM). Gilbert and co-workers investigated a series of benzofuran-3-one indole compounds as inhibitors of PI3 kinase-α and mTOR [112]. Such compounds can be considered as DIM analogues where one indole wing is replaced by a benzofuran-3-one moiety. The 5-methoxyindoles 17a–d showed the highest PI3K-α inhibition. PI3K-α docking results for 17a revealed binding of the 5-methoxy group with the hinge region (Val851), the hydroxyl groups bind to the catalytic Lys802. Within these four compounds 17a–d, it became apparent that additional indole substituents at position 2 (17b–d, methyl-, phenyl-, 3-pyridyl-) led to stronger PI3K-α inhibition (IC50 = 1–3 nM) compared with 17a (IC50 = 30 nM). In addition, indoles 17b–d significantly inhibited mTOR (IC50 = 3 nM for 17b, 10 nM for 17c, and 1 nM for 17d). All in all, 17d exhibited the strongest PI3K-α and mTOR inhibition (IC50 = 1 nM). However, 17c showed the highest growth inhibitory activity in LoVo colon carcinoma (IC50 = 1.2 µM) and PC-3 prostate carcinoma cells (IC50 = 0.8 µM) as well as inhibition of Thr308 phosphorylation on AKT proteins at 1 µM. A new 5-ureidobenzofuranone-indole 18 was disclosed by Zhang, et al. and shown to be a potent dual inhibitor of PI3K and mTOR [113]. Indole 18 exerted a sub-nanomolar kinase inhibition (IC50 = 0.2 nM, PI3Kα; IC50 = 0.3 nM, mTOR) and it inhibited MDA-MB-361 breast cancer cell growth (IC50 < 3 nM). Compound 18 (25 mg/kg) efficiently blocked AKT phosphorylation (= activation) in nude mice and led to drastic tumor regressions of MDA-MB-361 breast cancer xenografts. These promising results warrant further in-depth investigations of compound 18.

Fig. (5).

Structures of heterocycle-connected indole derivatives with AKT/mTOR-modulatory activity.

FUNCTIONAL IMPLICATIONS OF PI3K/Akt/mTOR/NF-κB INHIBITION BY I3C AND DIM: POTENTIAL ROLE IN EMT REVERSAL AND microRNA (miRNA) REGULATION

A review of available literature on the anticancer activity of indoles, as discussed in the sections above, provides an insight into their mechanism of action. These compounds inhibit multiple factors within the PI3K/Akt/mTOR/NF-κB signaling pathway, in addition to several independent signaling pathways, resulting in efficient induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest. The reports on the modulation of Akt-NF-κB by representative compounds, especially DIM, keep pouring in and some very recent reports have evaluated their anticancer activity in many diverse cancer models. As encouraging as these reports are, demonstrating the efficacy of these compounds against diverse human cancers, the mechanism(s) of action of these compounds largely remain unexplored. In particular, not much is known about how these compounds influence the migration, invasion, metastasis and angiogenesis of cancer cells.

In recent years the process of epithelial-to-mesenchymal-transition (EMT) has been implicated in the acquisition of aggressiveness of cancer cells, including their increased migration, invasion and metastasis capacity [114–116]. The role of PI3K/Akt/mTOR/NF-κB signaling in the induction of EMT has been well-documented [117–119]. Given this relationship, it is possible that the observed inhibitory effects of indoles on invasion and metastasis of cancer cells can be due to the regulation of PI3K/Akt/mTOR/NF-κB-mediated EMT. This question largely remains unanswered but preliminary observations have suggested this to be true. In one of the first report documenting the ability of natural compounds, especially DIM, to modulate EMT [120], we reported the reversal of EMT in pancreatic cancer cells after the cells were treated with DIM. We observed that the gemcitabine-resistant pancreatic cancer cells exhibit a change in morphology and characteristics consistent with the acquisition of EMT, which was associated with their aggressive behavior. When treated with DIM, we found decreased expression of mesenchymal markers vimentin, slug and ZEB1, all of which suggest reversal of EMT. Although this was the first report documenting such modulation of EMT by a natural agent, emerging evidence is supportive of such action and it is now being realized that several natural agents possess this activity [121].

Loss or gain of certain microRNAs (miRNAs) has also been linked to EMT and the aggressive phenotype of cancer cells [115,116]. In our work discussed above, we observed an up-regulation of several miRNAs in DIM-treated cells. These miRNAs belonging to miR-200 and let-7 families are known to be negative regulators of EMT [121]. Their up-regulation by DIM provided the mechanism by which DIM can reverse EMT. The miRNAs are known to regulate NF-κB signaling [122,123], thus providing a link between PI3K/Akt/mTOR/NF-κB signaling and miRNAs. A very direct connection between PI3K/Akt/mTOR/NF-κB, DIM and miRNAs has not been fully evaluated and should be the subject of future mechanistic research. As further evidence in support of the ability of DIM to influence both EMT and miRNAs, our recent findings showed down-regulation of miR-92a in DIM-treated prostate cancer cells [124]. This inhibition was found to be important for the reversal of EMT and remodeling of bone in the context of bone metastasis of prostate cancer.

CONCLUSIONS

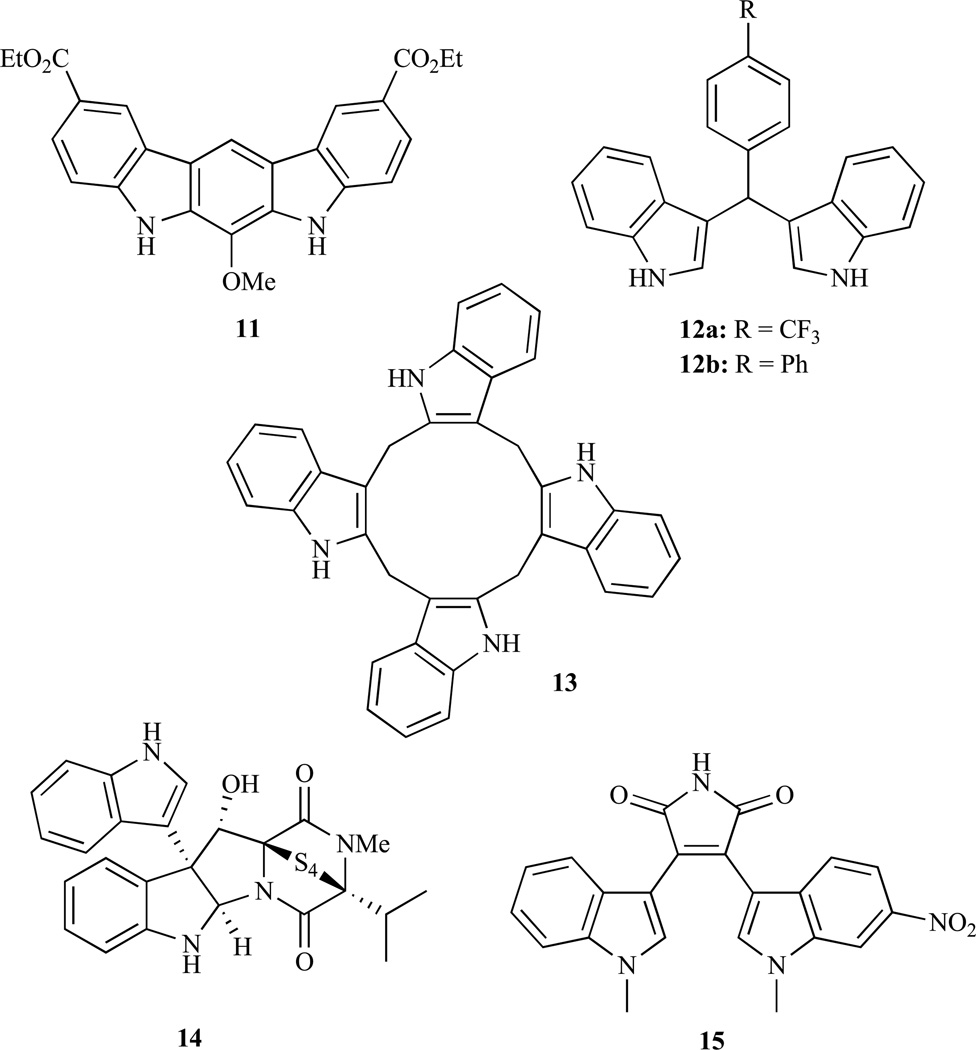

Indole compounds, particularly I3C and DIM, have demonstrated remarkable inhibition of invasion and metastasis of multiple cancer cells; however, their mechanism of action is not well understood. Being pleiotropic in nature, these compounds modulate multiple signaling pathways and PI3K/Akt/mTOR/NF-κB is one such signaling net-work. In particular, a lot of information is available on the ability of these compounds to inhibit Akt and NF-κB activation which seems to suggest that Akt and NF-κB represent two main targets of these compounds (Fig. 6). With experimental progress of these indoles through pre-clinical studies, concerns have been raised about their stability and bioavailability. This has been partially answered through the use of proprietary formulation of DIM, such as BR-DIM that demonstrates considerably increased bioavailability. A number of research groups have synthesized novel analogs and our own laboratory is actively pursuing this approach. Some very recent work from our laboratory has suggested a modulation of novel miRNAs by DIM, leading to the reversal of EMT. This novel research has provided new insight into the mechanism of action of these natural compounds, and thus it is expected that this review will spark more mechanistic studies to fully understand this process.

Fig. (6).

Schematic representation of inhibition of PI3K/Akt/mTOR/NF-κB signaling by indole compounds I3C and DIM.

The number of I3C-derived compounds with modulatory influence on the AKT/mTOR pathway as presented in this review article demonstrates the potential of this compound class as future drugs against AKT dependent diseases, most importantly for the treatment of human malignancies. The vast majority of these compounds inhibit AKT/mTOR signaling either via direct interaction with proteins involved in this pathway, like PI3K and mTOR, or via mechanisms that are still unknown, suggesting that further in-depth biological research is warranted. In some cases AKT/mTOR inhibition (e.g., 10) was also associated with induction of programmed cell death and autophagy, which differs mechanistically from apoptosis. This discovery opens newer opportunity toward the treatment of cancer especially those resistant to apoptosis induction. Apart from those that have been focussed on in this review article, there are still a host of natural indole compounds out there for which we know virtually nothing in terms of their anticancer activity; however, further investigation would be important for assessing their applicability in the clinical settings. In our judgment, the indole-associated class of agents constitute a huge reservoir of potential new drugs, which must be fully exploited for assessing their anti-cancer activity both in pre-clinical and in clinical setting. Nevertheless, this review already presents a couple of new indole derivatives with excellent in vivo activity, a necessary prerequisite for the design of clinical trials with cancer patients. And the Brassica indoles, I3C and DIM are already undergoing clinical trials both for the treatment and for the prevention of cancer. Yet, more work in this field is needed and with advances in research and clinical testing will ultimately uncover the utility of indole-drugs for the treatment of human malignancies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2012;62:10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sarkar FH, Li Y, Wang Z, Kong D. Cellular signaling perturbation by natural products. Cell Signal. 2009;21:1541–1547. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee M M, Gomez SL, Chang JS, Wey M, Wang RT, Hsing AW. Soy and isoflavone consumption in relation to prostate cancer risk in China. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12:665–668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarkar FH, Li Y. Harnessing the fruits of nature for the development of multi-targeted cancer therapeutics. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2009;35:597–607. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmad A, Sakr WA, Rahman KM. Anticancer properties of indole compounds: mechanism of apoptosis induction and role in chemotherapy. Curr. Drug Targets. 2010;11:652–666. doi: 10.2174/138945010791170923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim YS, Milner JA. Targets for indole-3-carbinol in cancer prevention. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2005;16:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aggarwal BB, Ichikawa H. Molecular targets and anticancer potential of indole-3-carbinol and its derivatives. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:1201–1215. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.9.1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rogan EG. The natural chemopreventive compound indole-3-carbinol: state of the science. In Vivo. 2006;20:221–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Safe S, Papineni S, Chintharlapalli S. Cancer chemotherapy with indole-3-carbinol, bis(3'-indolyl)methane and synthetic analogs. Cancer Lett. 2008;269:326–338. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bradlow HL. Review. Indole-3-carbinol as a chemoprotective agent in breast and prostate cancer. In Vivo. 2008;22:441–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Acharya A, Das I, Singh S, Saha T. Chemopreventive properties of indole-3-carbinol, diindolylmethane and other constituents of cardamom against carcinogenesis. Recent Pat. Food Nutr. Agric. 2010;2:166–177. doi: 10.2174/2212798411002020166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarkar FH, Li Y. Indole-3-carbinol and prostate cancer. J. Nutr. 2004;134:3493S–3498S. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.12.3493S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weng JR, Tsai CH, Kulp SK, Chen CS. Indole-3-carbinol as a chemopreventive and anti-cancer agent. Cancer Lett. 2008;262:153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmad A, Sakr WA, Rahman KMW. Role of Nuclear Factor-kappa B Signaling in Anticancer Properties of Indole Compounds. J.Exp. Clin.Med. 2011;3:55–62. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steinmetz KA, Potter JD. Vegetables, fruit, and cancer prevention: a review. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1996;96:1027–39. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(96)00273-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Michaud DS, Spiegelman D, Clinton SK, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Giovannucci EL. Fruit and vegetable intake and incidence of bladder cancer in a male prospective cohort. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1999;91:605–613. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.7.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson IS, Armstrong JG, Gorman M, Burnett JP., Jr. The Vinca alkaloids: a new class of oncolytic agents. Cancer Res. 1963;23:1390–1427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Omura S, Iwai Y, Hirano A, Nakagawa A, Awaya J, Tsuchya H, Takahashi Y, Masuma R. A new alkaloid AM-2282 OF Streptomyces origin. Taxonomy, fermentation, isolation and preliminary characterization. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 1977;30:275–282. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.30.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barrios CH, Liu MC, Lee SC, Vanlemmens L, Ferrero JM, Tabei T, Pivot X, Iwata H, Aogi K, Lugo-Quintana R, Harbeck N, Brickman MJ, Zhang K, Kern KA, Martin M. Phase III randomized trial of sunitinib versus capecitabine in patients with previously treated HER2-negative advanced breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2010;121:121–131. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0788-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mina L, Krop I, Zon RT, Isakoff SJ, Schneider CJ, Yu M, Johnson C, Vaughn LG, Wang Y, Hristova-Kazmierski M, Shonukan OO, Sledge GW, Miller KD. A phase II study of oral enzastaurin in patients with metastatic breast cancer previously treated with an anthracycline and a taxane containing regimen. Invest. New Drug. 2009;27(6):565–570. doi: 10.1007/s10637-009-9220-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oganesian A, Hendricks JD, Williams DE. Long term dietary indole-3-carbinol inhibits diethylnitrosamine-initiated hepato-carcinogenesis in the infant mouse model. Cancer Lett. 1997;118:87–94. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(97)00235-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jin L, Qi M, Chen DZ, Anderson A, Yang GY, Arbeit JM, Auborn KJ. Indole-3-carbinol prevents cervical cancer in human papilloma virus type 16 (HPV16) transgenic mice. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3991–3997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.He YH, Friesen MD, Ruch RJ, Schut HA. Indole-3-carbinol as a chemopreventive agent in 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo [4, 5-b]pyridine (PhIP) carcinogenesis: inhibition of PhIP-DNA adduct formation, acceleration of PhIP metabolism, and induction of cytochrome P450 in female F344 rats. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2000;38:15–23. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(99)00117-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kojima T, Tanaka T, Mori H. Chemoprevention of spontaneous endometrial cancer in female Donryu rats by dietary indole-3-carbinol. Cancer Res. 1994;54:1446–1449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wong GY, Bradlow L, Sepkovic D, Mehl S, Mailman J, Osborne MP. Dose-ranging study of indole-3-carbinol for breast cancer prevention. J. Cell Biochem. Suppl. 1997;28–29:111–116. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(1997)28/29+<111::aid-jcb12>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yuan F, Chen DZ, Liu K, Sepkovic DW, Bradlow HL, Auborn K. Anti-estrogenic activities of indole-3-carbinol in cervical cells: implication for prevention of cervical cancer. Anticancer Res. 1999;19:1673–1680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Verhoeven DT, Verhagen H, Goldbohm RA, van den Brandt PA, van PG. A review of mechanisms underlying anticarcinogenicity by brassica vegetables. Chem. Biol. Interact. 1997;103:79–129. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(96)03745-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holst B, Williamson G. A critical review of the bioavailability of glucosinolates and related compounds. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2004;21:425–447. doi: 10.1039/b204039p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McDanell R, McLean AE, Hanley AB, Heaney RK, Fenwick GR. The effect of feeding brassica vegetables and intact glucosinolates on mixed-function-oxidase activity in the livers and intestines of rats. Food Chem. Toxicol. 1989;27:289–293. doi: 10.1016/0278-6915(89)90130-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Terry P, Wolk A, Persson I, Magnusson C. Brassica vegetables and breast cancer risk. JAMA. 2001;285:2975–2977. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.23.2975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van PG, Verhoeven DT, Verhagen H, Goldbohm RA. Brassica vegetables and cancer prevention. Epidemiology and mechanisms. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1999;472:159–168. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-3230-6_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verhagen H, Poulsen HE, Loft S, van Poppel G, Willems MI, van Bladeren PJ. Reduction of oxidative DNA-damage in humans by brussels sprouts. Carcinogenesis. 1995;16:969–970. doi: 10.1093/carcin/16.4.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keck AS, Finley JW. Cruciferous vegetables: cancer protective mechanisms of glucosinolate hydrolysis products and selenium. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2004;3:5–12. doi: 10.1177/1534735403261831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grubbs CJ, Steele VE, Casebolt T, Juliana MM, Eto I, Whitaker LM, Dragnev KH, Kelloff GJ, Lubet RL. Chemoprevention of chemically-induced mammary carcinogenesis by indole-3-carbinol. Anticancer Res. 1995;15:709–716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shertzer HG, Senft AP. The micronutrient indole-3-carbinol: implications for disease and chemoprevention. Drug Metabol. Drug Interact. 2000;17:159–188. doi: 10.1515/dmdi.2000.17.1-4.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dashwood RH, Fong AT, Arbogast DN, Bjeldanes LF, Hendricks JD, Bailey GS. Anticarcinogenic activity of indole-3-carbinol acid products: ultrasensitive bioassay by trout embryo microinjection. Cancer Res. 1994;54:3617–3619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shaw RJ, Cantley LC. Ras, PI(3)K and mTOR signalling controls tumour cell growth. Nature. 2006;441:424–430. doi: 10.1038/nature04869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luo J, Manning BD, Cantley LC. Targeting the PI3K-Akt pathway in human cancer: rationale and promise. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:257–262. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00248-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manning BD, Cantley LC. United at last: the tuberous sclerosis complex gene products connect the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt pathway to mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signalling. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2003;31:573–578. doi: 10.1042/bst0310573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hay N. The Akt-mTOR tango and its relevance to cancer. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:179–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.LoPiccolo J, Blumenthal GM, Bernstein WB, Dennis PA. Targeting the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway: effective combinations and clinical considerations. Drug Resist. Updat. 2008;11:32–50. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Falasca M, Selvaggi F, Buus R, Sulpizio S, Edling CE. Targeting phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathways in pancreatic cancer--from molecular signalling to clinical trials. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2011;11:455–463. doi: 10.2174/187152011795677382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nahta R, O'Regan RM. Evolving strategies for overcoming resistance to HER2-directed therapy: targeting the PI3K/Akt/ mTOR pathway. Clin. Breast Cancer. 2010;10(Suppl 3):S72–S78. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2010.s.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Karin M, Cao Y, Greten FR, Li ZW. NF-kappaB in cancer: from innocent bystander to major culprit. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2002;2:301–310. doi: 10.1038/nrc780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karin M. Nuclear factor-kappaB in cancer development and progression. Nature. 2006;441:431–436. doi: 10.1038/nature04870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lin Y, Bai L, Chen W, Xu S. The NF-kappaB activation pathways, emerging molecular targets for cancer prevention and therapy. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets. 2010;14:45–55. doi: 10.1517/14728220903431069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li F, Sethi G. Targeting transcription factor NF-kappaB to overcome chemoresistance and radioresistance in cancer therapy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1805:167–180. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ahmad A, Banerjee S, Wang Z, Kong D, Majumdar AP, Sarkar FH. Aging and inflammation: etiological culprits of cancer. Curr. Aging Sci. 2009;2:174–186. doi: 10.2174/1874609810902030174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luqman S, Pezzuto JM. NFkappaB: a promising target for natural products in cancer chemoprevention. Phytother. Res. 2010;24:949–963. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Staudt LM. Oncogenic activation of NF-kappaB. Cold Spring Harb Perspect. Biol. 2010;2:a000109. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ozes ON, Mayo LD, Gustin JA, Pfeffer SR, Pfeffer LM, Donner DB. NF-kappaB activation by tumour necrosis factor requires the Akt serine-threonine kinase. Nature. 1999;401:82–85. doi: 10.1038/43466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Romashkova JA, Makarov SS. NF-kappaB is a target of AKT in anti-apoptotic PDGF signalling. Nature. 1999;401:86–90. doi: 10.1038/43474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meng F, Liu L, Chin PC, D'Mello SR. Akt is a downstream target of NF-kappa B. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:29674–29680. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112464200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Salminen A, Kaarniranta K. Insulin/IGF-1 paradox of aging: regulation via AKT/IKK/NF-kappaB signaling. Cell Signal. 2010;22:573–577. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dan HC, Cooper MJ, Cogswell PC, Duncan JA, Ting JP, Baldwin AS. Akt-dependent regulation of NF-{kappa}B is controlled by mTOR and Raptor in association with IKK. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1490–500. doi: 10.1101/gad.1662308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chinni SR, Sarkar FH. Akt inactivation is a key event in indole-3-carbinol-induced apoptosis in PC-3 cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2002;8:1228–1236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rahman KM, Li Y, Sarkar FH. Inactivation of akt and NF-kappaB play important roles during indole-3-carbinol-induced apoptosis in breast cancer cells. Nutr. Cancer. 2004;48:84–94. doi: 10.1207/s15327914nc4801_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kassie F, Kalscheuer S, Matise I, Ma L, Melkamu T, Upadhyaya P, Hecht SS. Inhibition of vinyl carbamate-induced pulmonary adenocarcinoma by indole-3-carbinol and myo-inositol in A/J mice. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:239–245. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kassie F, Melkamu T, Endalew A, Upadhyaya P, Luo X, Hecht SS. Inhibition of lung carcinogenesis and critical cancer-related signaling pathways by N-acetyl-S-(N-2-phenethylthiocarbamoyl)-l-cysteine, indole-3-carbinol and myo-inositol, alone and in combination. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:1634–1641. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kassie F, Matise I, Negia M, Upadhyaya P, Hecht SS. Dose-dependent inhibition of tobacco smoke carcinogen-induced lung tumorigenesis in A/J mice by indole-3-carbinol. Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila) 2008;1:568–576. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dagne A, Melkamu T, Schutten MM, Qian X, Upadhyaya P, Luo X, Kassie F. Enhanced inhibition of lung adenocarcinoma by combinatorial treatment with indole-3-carbinol and silibinin in A/J mice. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:561–567. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Qian X, Melkamu T, Upadhyaya P, Kassie F. Indole-3-carbinol inhibited tobacco smoke carcinogen-induced lung adenocarcinoma in A/J mice when administered during the post-initiation or progression phase of lung tumorigenesis. Cancer Lett. 2011;311:57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nakamura Y, Yogosawa S, Izutani Y, Watanabe H, Otsuji E, Sakai T. A combination of indol-3-carbinol and genistein synergistically induces apoptosis in human colon cancer HT-29 cells by inhibiting Akt phosphorylation and progression of autophagy. Mol. Cancer. 2009;8:100. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-8-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chao WR, Yean D, Amin K, Green C, Jong L. Computer-aided rational drug design: a novel agent (SR13668) designed to mimic the unique anticancer mechanisms of dietary indole-3-carbinol to block Akt signaling. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:3412–3415. doi: 10.1021/jm070040e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Weng JR, Bai LY, Omar HA, et al. A novel indole-3-carbinol derivative inhibits the growth of human oral squamous cell carcinoma in vitro. Oral Oncol. 2010;46:748–754. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.De SM, Galluzzi L, Lucarini S, Paoletti MF, Fraternale A, Duranti A, De Marco C, Fanelli M, Zaffaroni N, Brandi G, Magnani M. The indole-3-carbinol cyclic tetrameric derivative CTet inhibits cell proliferation via overexpression of p21/CDKN1A in both estrogen receptor-positive and triple-negative breast cancer cell lines. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13:R33. doi: 10.1186/bcr2855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kim DJ, Reddy K, Kim MO, Li Y, Nadas J, Cho YY, Kim JE, Shim JH, Song NR, Carper A, Lubet RA, Bode AM, Dong Z. (3-Chloroacetyl)-indole, a novel allosteric AKT inhibitor, suppresses colon cancer growth in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila) 2011;4:1842–1851. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hwang JW, Jung JW, Lee YS, Kang KS. Indole-3-carbinol prevents H(2)O(2)-induced inhibition of gap junctional intercellular communication by inactivation of PKB/Akt. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2008;70:1057–1063. doi: 10.1292/jvms.70.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li Y, Chinni SR, Sarkar FH. Selective growth regulatory and pro-apoptotic effects of DIM is mediated by AKT and NF-kappaB pathways in prostate cancer cells. Front Biosci. 2005;10:236–243. doi: 10.2741/1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rahman KW, Sarkar FH. Inhibition of nuclear translocation of nuclear factor-{kappa}B contributes to 3, 3'-diindolylmethane-induced apoptosis in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:364–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Garikapaty VP, Ashok BT, Tadi K, Mittelman A, Tiwari RK. Synthetic dimer of indole-3-carbinol: second generation diet derived anti-cancer agent in hormone sensitive prostate cancer. Prostate. 2006;66:453–462. doi: 10.1002/pros.20350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Garikapaty VP, Ashok BT, Tadi K, Mittelman A, Tiwari RK. 3, 3'-Diindolylmethane downregulates pro-survival pathway in hormone independent prostate cancer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;340:718–725. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bhuiyan MM, Li Y, Banerjee S, et al. Down-regulation of androgen receptor by 3, 3'-diindolylmethane contributes to inhibition of cell proliferation and induction of apoptosis in both hormone-sensitive LNCaP and insensitive C4-2B prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10064–10072. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang Z, Yu BW, Rahman KM, Ahmad F, Sarkar FH. Induction of growth arrest and apoptosis in human breast cancer cells by 3, 3-diindolylmethane is associated with induction and nuclear localization of p27kip. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2008;7:341–349. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kong D, Banerjee S, Huang W, et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin repression by 3, 3'-diindolylmethane inhibits invasion and angiogenesis in platelet-derived growth factor-D-overexpressing PC3 cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1927–1934. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rajoria S, Suriano R, Wilson YL, et al. 3, 3'-diindolylmethane inhibits migration and invasion of human cancer cells through combined suppression of ERK and AKT pathways. Oncol. Rep. 2011;25:491–497. doi: 10.3892/or.2010.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Guan H, Zhu L, Fu M, et al. 3, 3'Diindolylmethane suppresses vascular smooth muscle cell phenotypic modulation and inhibits neointima formation after carotid injury. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34957. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chen Y, Xu J, Jhala N, et al. Fas-mediated apoptosis in cholangiocarcinoma cells is enhanced by 3, 3'-diindolylmethane through inhibition of AKT signaling and FLICE-like inhibitory protein. Am. J. Pathol. 2006;169:1833–1842. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gao N, Cheng S, Budhraja A, et al. 3, 3'-Diindolylmethane exhibits antileukemic activity in vitro and in vivo through a Akt-dependent process. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31783. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 80.Zhu J, Li Y, Guan C, Chen Z. Anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic effects of 3, 3'-diindolylmethane in human cervical cancer cells. Oncol. Rep. 2012;28:1063–1068. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Weng JR, Bai LY, Chiu CF, Wang YC, Tsai MH. The dietary phytochemical 3, 3'-diindolylmethane induces G2/M arrest and apoptosis in oral squamous cell carcinoma by modulating Akt-NF-kappaB, MAPK, and p53 signaling. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2012;195:224–230. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kunimasa K, Kobayashi T, Kaji K, Ohta T. Antiangiogenic effects of indole-3-carbinol and 3, 3'-diindolylmethane are associated with their differential regulation of ERK1/2 and Akt in tube-forming HUVEC. J. Nutr. 2010;140:1–6. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.112359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sarkar FH, Li Y. Using chemopreventive agents to enhance the efficacy of cancer therapy. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3347–3350. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rahman KM, Ali S, Aboukameel A, et al. Inactivation of NF-kappaB by 3, 3'-diindolylmethane contributes to increased apoptosis induced by chemotherapeutic agent in breast cancer cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2007;6:2757–2765. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ichite N, Chougule M, Patel AR, et al. Inhalation delivery of a novel diindolylmethane derivative for the treatment of lung cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2010;9:3003–3014. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Banerjee S, Kong D, Wang Z, et al. Attenuation of multi-targeted proliferation-linked signaling by 3, 3'-diindolylmethane (DIM): from bench to clinic. Mutat. Res. 2011;728:47–66. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gitto R, De LL, Ferro S, et al. Development of 3-substituted-1H–indole derivatives as NR2B/NMDA receptor antagonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009;17:1640–1647. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.12.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Li Q, Li T, Zhu GD, et al. Discovery of trans-3, 4'-bispyridinylethylenes as potent and novel inhibitors of protein kinase B (PKB/Akt) for the treatment of cancer: Synthesis and biological evaluation. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006;16:1679–1685. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhu GD, Gandhi VB, Gong J, et al. Discovery and SAR of oxindole-pyridine-based protein kinase B/Akt inhibitors for treating cancers. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006;16:3424–3429. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Guo W, Wu S, Liu J, Fang B. Identification of a small molecule with synthetic lethality for K-ras and protein kinase C iota. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7403–7408. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wu S, Wang L, Guo W, et al. Analogues and derivatives of oncrasin-1, a novel inhibitor of the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II and their antitumor activities. J. Med. Chem. 2011;54:2668–2679. doi: 10.1021/jm101417n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Carbonnelle D, Duflos M, Marchand P, et al. A novel indole-3-propanamide exerts its immunosuppressive activity by inhibiting JAK3 in T cells. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2009;331:710–716. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.155986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Singh RK, Lange TS, Kim K, et al. Effect of indole ethyl isothiocyanates on proliferation, apoptosis, and MAPK signaling in neuroblastoma cell lines. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007;17:5846–5852. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Singh RK, Lange TS, Kim KK, et al. Isothiocyanate NB7M causes selective cytotoxicity, pro-apoptotic signalling and cell-cycle regression in ovarian cancer cells. Br. J. Cancer. 2008;99:1823–1831. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Brard L, Singh RK, Kim KK, Lange TS, Sholler GL. Induction of cytotoxicity, apoptosis and cell cycle arrest by 1-t-butyl carbamoyl, 7-methyl-indole-3-ethyl isothiocyanate (NB7M) in nervous system cancer cells. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2009;2:61–69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Weng JR, Tsai CH, Kulp SK, et al. A potent indole-3-carbinol derived antitumor agent with pleiotropic effects on multiple signaling pathways in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7815–7824. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Weng JR, Tsai CH, Omar HA, et al. OSU-A9, a potent indole-3-carbinol derivative, suppresses breast tumor growth by targeting the Akt-NF-kappaB pathway and stress response signaling. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:1702–1709. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Omar HA, Sargeant AM, Weng JR, et al. Targeting of the Akt-nuclear factor-kappa B signaling network by [1-(4-chloro-3-nitrobenzenesulfonyl)-1H–indol-3-yl]-methanol (OSU-A9), a novel indole-3-carbinol derivative, in a mouse model of hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol. Pharmacol. 2009;76:957–968. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.058180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sarkaria JN, Tibbetts RS, Busby EC, et al. Inhibition of phosphoinositide 3-kinase related kinases by the radiosensitizing agent wortmannin. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4375–4382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ding H, Zhang C, Wu X, et al. Novel indole alpha-methylene-gamma-lactones as potent inhibitors for AKT-mTOR signaling pathway kinases. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005;15:4799–4802. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zhang C, Yang N, Yang CH, et al. S9, a novel anticancer agent, exerts its anti-proliferative activity by interfering with both PI3K-Akt-mTOR signaling and microtubule cytoskeleton. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4881. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Jobson AG, Lountos GT, Lorenzi PL, et al. Cellular inhibition of checkpoint kinase 2 (Chk2) and potentiation of camptothecins and radiation by the novel Chk2 inhibitor PV1019 [7-nitro-1H–indole-2-carboxylic acid {4-[1-(guanidinohydrazone)-ethyl]-phenyl}-amide] J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2009;331:816–826. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.154997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Finlay MR, Buttar D, Critchlow SE, et al. Sulfonyl-morpholino-pyrimidines: SAR and development of a novel class of selective mTOR kinase inhibitor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012;22:4163–4168. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Viola G, Bortolozzi R, Hamel E, Moro S, Brun P, Castagliuolo I, Ferlin MG, Basso G. MG-2477, a new tubulin inhibitor, induces autophagy through inhibition of the Akt/mTOR pathway and delayed apoptosis in A549 cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2012;83:16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gasparotto V, Castagliuolo I, Ferlin MG. 3-substituted 7-phenyl-pyrroloquinolinones show potent cytotoxic activity in human cancer cell lines. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:5509–5513. doi: 10.1021/jm070534b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chintharlapalli S, Papineni S, Safe S. 1, 1-Bis(3'-indolyl)-1-(p-substituted phenyl)methanes inhibit colon cancer cell and tumor growth through PPARgamma-dependent and PPARgamma-independent pathways. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2006;5:1362–1370. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Takahashi C, Numata A, Ito Y, Matsumura E, Araki H, Iwaki H, Kushida K. Leptosins, antitumour metabolites of a fungus isolated from a marine alga. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1994;1:1859–1864. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Yanagihara M, Sasaki-Takahashi N, Sugahara T, Yamamoto S, Shinomi M, Yamashita I, Hayashida M, Yamanoha B, Numata A, Yamori T, Andoh T. Leptosins isolated from marine fungus Leptoshaeria species inhibit DNA topoisomerases I and/or II and induce apoptosis by inactivation of Akt/protein kinase B. Cancer Sci. 2005;96:816–824. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2005.00117.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Karaman MW, Herrgard S, Treiber DK, Gallant P, Atteridge CE, Campbell BT, Chan KW, Ciceri P, Davis MI, Edeen PT, Faraoni R, Floyd M, Hunt JP, Lockhart DJ, Milanov ZV, Morrison MJ, Pallares G, Patel HK, Pritchard S, Wodicka LM, Zarrinkar PP. A quantitative analysis of kinase inhibitor selectivity. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008;26:127–132. doi: 10.1038/nbt1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Tevaarwerk A, Wilding G, Eickhoff J, Chappell R, Sidor C, Arnott J, Bailey H, Schelman W, Liu G. Phase I study of continuous MKC-1 in patients with advanced or metastatic solid malignancies using the modified Time-to-Event Continual Reassessment Method (TITE-CRM) dose escalation design. Invest. New Drugs. 2012;30:1039–1045. doi: 10.1007/s10637-010-9629-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Dowling JE, Chuaqui C, Pontz TW, Lyne PD, Larsen NA, Block MH, Chen H, Su N, Wu A, Russell D, Pollard H, Lee JW, Peng B, Thakur K, Ye Q, Zhang T, Brassil P, Racicot V, Bao L, Denz CR, Cooke E. Potent and Selective Inhibitors of CK2 Kinase Identified through Structure-Guided Hybridization. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2012;3:278–283. doi: 10.1021/ml200257n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Bursavich MG, Brooijmans N, Feldberg L, Hollander I, Kim S, Lombardi S, Park K, Mallon R, Gilbert AM. Novel benzofuran-3-one indole inhibitors of PI3 kinase-alpha and the mammalian target of rapamycin: hit to lead studies. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010;20:2586–2590. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.02.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Zhang N, Ayral-Kaloustian S, Anderson JT, Nguyen T, Das S, Venkatesan AM, Brooijmans N, Lucas J, Yu K, Hollander I, Mallon R. 5-ureidobenzofuranone indoles as potent and efficacious inhibitors of PI3 kinase-alpha and mTOR for the treatment of breast cancer. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010;20:3526–3529. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.04.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Iwatsuki M, Mimori K, Yokobori T, Ishi H, Beppu T, Nakamori S, Baba H, Mori M. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer development and its clinical significance. Cancer Sci. 2010;101:293–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01419.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wang Z, Li Y, Ahmad A, Azmi AS, Kong D, Banerjee S, Sarkar FH. Targeting miRNAs involved in cancer stem cell and EMT regulation: An emerging concept in overcoming drug resistance. Drug Resist. Updat. 2010;13:109–118. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ahmad A, Aboukameel A, Kong D, Wang Z, Sethi S, Chen W, Sarkar FH, Raz A. Phosphoglucose isomerase/autocrine motility factor mediates epithelial-mesenchymal transition regulated by miR-200 in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2011;71:3400–3409. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Larue L, Bellacosa A. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in development and cancer: role of phosphatidylinositol 3'kinase/AKT pathways. Oncogene. 2005;24:7443–7454. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Lamouille S, Derynck R. Emergence of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase-Akt-mammalian target of rapamycin axis in transforming growth factor-beta-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Cells Tissues Organs. 2011;193:8–22. doi: 10.1159/000320172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Kasinski AL, Slack FJ. Potential microRNA therapies targeting Ras, NFkappaB and p53 signaling. Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther. 2010;12:147–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]