Abstract

This study compared adherence to Behavioral Choice Treatment (BCT), a 12-week obesity treatment program that promotes weight loss and exercise, among 22 Caucasian-American and 10 African-American overweight women in a university setting to 10 African-American overweight women in a church setting. Behavioral Choice Treatment (BCT) promotes moderate behavior change that can be comfortably and therefore permanently maintained.14 Participants obtained feedback from computerized eating diaries and kept exercise logs. Results indicated that both university groups exhibited comparable eating pathology at pre-and post-treatment and comparable weight loss, despite the African-American sample attending fewer sessions. The African-American church group exhibited less disordered eating attitudes, less interpersonal distrust (eg, reluctance to form close relationships or sense of alienation) at pre-treatment, and experienced significantly greater weight loss than either university group. All groups lost weight and maintained these losses at 12-month follow-up. Preliminary results suggest treatment setting may play an important role in treatment adherence and sample characteristics.

Keywords: Adherence, African Americans, Obesity Treatment, Weight Maintenance

Introduction

Obesity and overweight are major health problems in the United States, affecting more than 90 million adult Americans and a disproportionate percentage of ethnic minorities, women, and those from lower income and education groups.1,2 Obesity is also increasing. The Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHA-NES) showed that the prevalence of overweight among adults increased 8% over approximately the last decade, and more recent data from the 1999–2000 NHANES show a similar trend.3,4 The rationale for treating obesity comes from evidence that modest weight losses can not only prevent or reverse blood pressure elevations,5,6 but also have a favorable impact on obesity-related cardiovascular risk factors such as type 2 diabetes7 and hyperlipidemia.6,7 Because African-American women are more at risk for obesity/overweight and related morbidities, acceptable treatments must be developed for this population.

Treatment of Obesity

Behavioral programs have been the principle treatment for obesity, but such programs have been under attack because of high rates of relapse and questions regarding the health effects of both dieting and mild-to-moderate obesity.8–10 Such issues have led to a number of modifications to the basic behavioral programs.11 Programs now incorporate exercise, are generally longer, and provide extended follow-up support of some kind. “Nondieting” or “Undieting” programs have also been developed as a new behavioral paradigm to promote weight management, although the results from such studies have been mixed.12,13

The present study used Behavior Choice Treatment (BCT), a nondieting approach to weight management developed and evaluated by Sbrocco, Nedegaard, Stone, and Lewis.14 This approach attempts to teach participants to view eating as a choice and to eat and exercise in moderation. Sbrocco and colleagues compared BCT to traditional behavior therapy (TBT), emphasizing weight loss via reduced caloric intake, self-monitoring, stimulus control, and behavioral substitution. Interestingly, while TBT produced significantly greater weight reduction at post-treatment assessment, participants in this condition evidenced a tendency to regain weight during the one-year14 and two-year follow-up periods.15,16 Conversely, BCT was associated with a more gradual weight reduction at one year and two years post-treatment. However, >85% of participants in this study were Caucasian.

African Americans and Obesity

While African-American women constitute a disproportionately high percentage of adults who are overweight and obese, only a handful of controlled clinical outcome studies have examined weight loss among African Americans.1 Although evidence suggests that African-American women may report dieting as often as their Caucasian counterparts,17 they may be less likely to participate in weight loss programs,18 more likely to drop out of traditional psychosocial treatments,19 and have evidenced a tendency to lose less weight when they participate.20 For example, Kumanyika and colleagues assessed the effect of weight loss of African-American to that of Caucasian-American women on blood pressure.20 Of particular relevance to the present study, Caucasian Americans evidenced greater success in weight loss than African Americans from the behavioral program.

Kumanyika has suggested that poorer outcomes may be related to program content or program delivery rather than to participant characteristics.21 Furthermore, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Obesity Guidelines1 note that treatment approaches for overweight and obesity must be tailored to the needs of various patient groups. The major recommendations for implementing culturally sensitive treatments include adapting the treatment setting and staffing, integrating treatment into other self-care, and allowing modifications based on participants’ feedback and response.

Several studies have evaluated the impact of programs developed specifically for use with African Americans. For example, the Black American Lifestyle Intervention (BALI) program was developed for use by “working-class” African Americans.22 Ethnic minority professionals reviewed all materials, and an African-American nutritionist led groups. McNabb and colleagues examined the efficacy of a behavioral weight loss program that emphasized an increase in general well-being rather than improved physical appearance as the goal of treatment.23 In addition, this program encouraged participants to identify their dietary problems and to arrive at personally relevant solutions. Also unique to this program was extensive use of ethnic foods and food combinations and the church-based setting. The results indicated that treated African-American women lost significantly more weight than those in a wait-list condition.

To date, several weight reduction interventions have been conducted in churches.23,24 This method is conceptualized as an effective means to reach African Americans.25 Most churches have a “health ministry,” including identified “nurses,” and churches often sponsor health-related activities.26 Such programs are considered effective among African Americans because of the central role of churches in exchanging information, as social networks, and as social support for many African Americans.27,28 Social networking may reduce the potential anxiety and distrust toward research that sometimes exists among ethnic minority populations.19,29 Davis and colleagues suggest that by appealing to the “collective identity of the congregation,” church-based interventions are able to use the inherent social support to reach those who might not otherwise seek support for their health concerns.30 Recent work examining the perceived health concerns of African-American church congregants found that 75% of the congregants surveyed were worried about their weight, exercise habits, diet, and salt intake.31 The church setting may also address prohibitions such as childcare and transportation. Church bulletins and announcements at weekly services and meetings provide a means for reaching members. The church has been employed as a partner to improve health among African Americans in several different contexts, including weight loss, hypertension management, and sexual behavior.24,25 Because many African Americans may already feel a connection and commitment to the church, the church may operate as a major tool for increasing participation in the formal delivery of health services.32

Obesity treatment programs need to be tailored to meet the needs of diverse groups, including African Americans, with recognition that diversity and overlap exist within cultural groups.1 The present study compared BCT, a cognitive behavioral intervention based on a decision-making model of women’s food choice,14 among African Americans in a church setting with a mixed sample of African Americans and Caucasian Americans in a university setting. We predicted that African Americans in the church setting would demonstrate better program adherence and, consequently, improved treatment outcome compared to African Americans in the university settings. Furthermore, African Americans in the church setting were expected to evidence treatment efficacy comparable to Caucasian Americans at the university. These differences were predicted based on group composition (predominately minority vs minority) and setting. The university group was chosen because it most closely represents the situation many minorities encounter when seeking treatment. The church setting was chosen because it has been suggested to be a key intervention site in previous research on such health problems as obesity and hypertension. In this regard, this study was one of a few obesity treatment outcome studies that examined factors associated with treatment success among African Americans and one of the first to examine eating behavior and attitudes between different samples of African Americans.

The major modification of the BCT protocol in the present study was the use of church treatment site. Group format, meeting times, and the basic menu plans or recipes were not modified. Consistent with McNabb and colleagues, discussions of eating culturally specific foods and modifying standard recipes as individuals brought up these issues did occur.23 This study represents an extension of ongoing work evaluating BCT, with the long term goal of improving weight maintenance.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 42 women between the ages of 18–55 years who were at least 30% above ideal body weight (determined by the 1983 Metropolitan Height Weight charts for a medium frame)33 living in the greater Metropolitan Washington, DC, area, a diverse area where approximately 60% of the population is Caucasian and almost 20% is African American. The university sample consisted of 32 women (10 African Americans) recruited through newspaper advertisement to participate in five groups conducted over a two-year period. Two African-American women were in each group of approximately 5–10 participants. All women participated in BCT, a 13-session cognitive behavioral program (see below for description). The 10 African-American women church participants were recruited from two church congregations in Washington, DC. Five women from each church participated in the study. All participants were recruited to participate in a weight management study and were nonsmokers in good health, had not lost >10 pounds (4.54 kg) in the last month or >20 pounds (9.09 kg) in the last 6 months and had a physician’s approval for participation. Similar to other studies,34,35 participation in the subsequent weight management program was contingent on completion of two-weeks of pre-treatment food and exercise diaries.

Measures

Anthropomorphic Measures

Weight in kilograms was measured on a balance beam scale with participants wearing indoor clothing without shoes. We used pre-treatment weight and a weight change score (pre-treatment—post-treatment weight) for post-treatment weight loss. The same procedure was used to determine weight loss at three additional follow up points: three months, six months, and one year. Height, to the nearest half inch, was calculated at pre-treatment. Body mass index (BMI) in kg/m2 was calculated from the weight and height measurements.

Behavioral Adherence

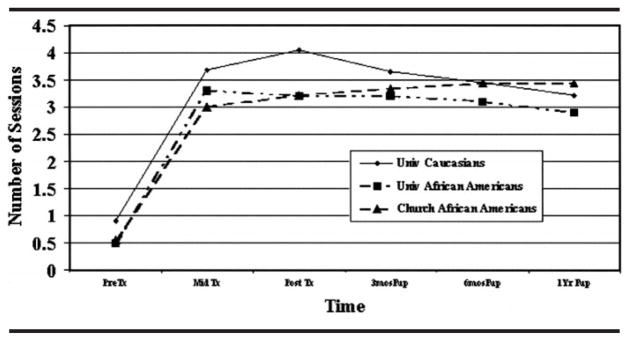

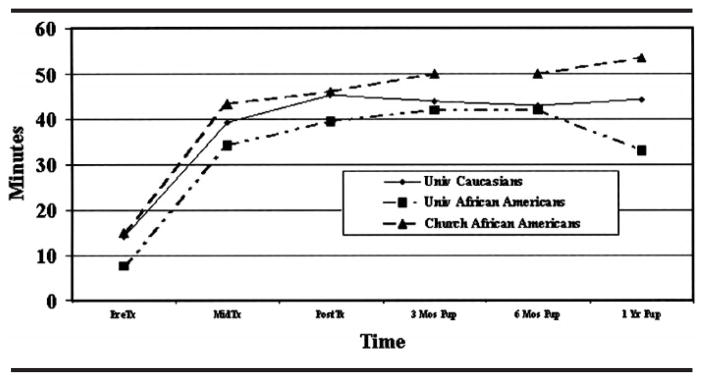

Session attendance and number of days of self-monitoring records were used as indices of adherence to the treatment program.36 Adherence to the exercise prescription was assessed by evaluating participants’ daily exercise logs consisting of the time and date, the activity completed, and the duration. Frequency of exercise is reported as number of exercise sessions completed per week at baseline and the average number of exercise session per week across treatment. In addition, the average length of time per exercise session in minutes is reported. Participants kept daily exercise logs during the active treatment phase and were asked to complete a weekly log at the time of each follow-up meeting. Results are presented in Figures 2 and 3.

Fig 2.

Average exercise sessions by group over time

Fig 3.

Average minutes per exercise session over time

Missed Session Protocol

Participants were asked to notify group leaders in advance if they were going to miss a session and arrange for a ½-hour session weigh-in and make-up. Participants who missed without prior notification were called within 2 days and asked to come in for a ½-hour make-up session.

Eating Patterns

Participants kept computerized self-monitoring diaries during pre-treatment and the first 10 weeks of treatment using the Psion 3.0A palmtop computer.37 This method has shown preliminary accuracy38 and is described in detail in the report of Sbrocco and colleagues.14 Dietary intake was recorded by using the Comcard COMPUTE-A-DIET Nutrient Balance System software program.39 Data from these logs were used to set goals, to provide immediate and weekly feedback to the participants, and to track caloric and macronutrient intakes. Adherence to caloric prescriptions was evaluated by examining the reported mean daily caloric intake by week and percentage of dietary fat by week.

Psychosocial Measures

Subjects completed the Eating Inventory (EI),40 and the Eating Disorders Inventory-2 (EDI-2),41 at pre-treatment and post-treatment. The EI is a 51-item inventory with restraint, disinhibition, and hunger subscales that have been shown to be useful among the obese.42 The EDI-2 is multi-scale instrument designed to assess behavioral and attitudinal characteristics clinically observed in eating disorders. Three subscales were used to examine various aspects of eating related pathology: drive for thinness, bulimia, and body dissatisfaction. In addition, three subscales assessed more general psychopathological constructs that are related to more pathological eating: internal awareness, ineffectiveness, and distrust. Lastly, summing all of the items created a total score for the EDI.

Procedure

The procedure for all groups was the same, except that all university groups were held at Uniformed Services University and the church groups were held at a church with a predominantly African-American congregation. All groups were led by the first author, a clinical psychologist, and two graduate student co-leaders. One of the two graduate student co-leaders was African-American and the other group leaders were Caucasian. An orientation was held to introduce the program and begin the baseline self-monitoring. Contingent on completion of the self-monitoring, participants were then assigned to a newly developed cognitive behavioral group treatment for weight loss.14 Ten percent of those who began self-monitoring did not complete the two-week baseline, and this did not differ by group. Each group was composed of 5–10 members and attended 13 weekly 1½-hour group sessions. Follow-up group meetings were conducted at 3 and 6 months post-treatment. Follow-up weights were obtained at 3, 6, and 12 months post-treatment. Retention of participants over time was successful for several reasons. First, participants are informed of the one-year duration of the study at pre-treatment. Also, we believe that the social support network that develops between participants at the weekly meetings, as well as a sense of attachment to the group leaders, helps to increase retention. Finally, monetary incentives were provided for participants who completed each phase of the study.

Behavioral Choice Treatment

Consistent with the procedure developed by Sbrocco and colleagues,14 participants in BCT were taught to stop dieting and to view health behaviors, including food choice, exercise avoidance, and eating behavior as choices, which achieve certain outcomes (eg, alleviate hunger, lose weight, feel better, and rest). Based on an understanding of the economics of their choices, participants restructured their thinking or behavior to enable them to achieve positive outcomes. Eating in moderation and eating reasonable amounts of high-fat or forbidden foods were identified as skill deficits that required practice, and these skills were promoted through extensive behavioral modeling in the group and through homework assignments. In addition, individuals were taught to examine their meaning of the word “dieting” and the inherent calorie restriction, avoid rigid rules about forbidden foods, engage in pleasurable activities besides eating, engage in regular exercise, and accept themselves regardless of their eating behavior and body weight. Participants were taught to focus on learning to eat in a manner consistent with a reasonable end goal weight that occurs “down the line,” rather than focusing on how quickly weight can be loss. Participants were told to expect much slower weight losses than they had experienced in the past, but that this approach was designed to produce permanent change. (A full description of the protocol can be found in Sbrocco et al.14)

All participants received two-week meal plans and recipe booklets. The eating plan was low fat with macronutrient composition as follows: 55%–60% carbohydrate, 20%–25% fat, 15%–20% protein, and 1800–2000 kcal/day (7534–8368 kJ). All participants were encouraged to adhere to these plans during the first two weeks in order to model new behavior. Diaries were downloaded onto an IBM-compatible PC during each weekly group meeting, where participants were provided with immediate feedback including graphs of daily calorie and daily fat intake and a list of their highest fat foods with lower fat alternatives. All participants were encouraged to eat at a constant calorie level in order to avoid the common pattern of over-restriction followed by overeating. Self-monitoring was phased out at session 10 before the acute treatment ended in order to address behavior change and concerns that arise from discontinuing self-monitoring. Participants were encouraged to complete a walking program (30 min/day, 3 days/week) in a single bout. Participants were not encouraged to exercise more than this, unless they were already exercising at a greater frequency or duration before entering the program. The goal, as explained as part of the BCT program, was to promote the adoption of reasonable behavior change patterns that could be maintained for life, versus an intensive exercise program that would change after reaching weight loss goals. Formal exercise groups were not held, and participants kept daily exercise logs.

Results

Demographic and Pre-Treatment Information

Demographic information is presented in Table 1. ANOVAs, conducted to examine for differences in age and education across groups, were nonsignificant (F(3, 44)=1.78, P=.18; F(3, 44) =2.14, P=.13, respectively). ANOVAs indicated groups differed on reported food intake at baseline (F(3, 42)=3.40, P<.05) but did not differ on weight (F(3, 44)=1.19, P<.10), BMI (F(3, 44) =2.39, P=.09), or percentage of dietary fat at baseline (F(3, 44)=2.96, P=.06). Contrasts indicated that the Caucasian-American group reported greater food intake than both the African-American university sample (t(39)=2.14, P<.05) and the African-American church sample (t(39)=2.06, P<.05). No differences were noted between the African-American samples (t(39)=.31, P=.75). Follow-up contrasts conducted to examine percentage of dietary fat consumed at baseline indicted that the Caucasian Americans’ diet was composed of significantly less fat than the African-American university sample (t(39)=2.32, P<.05). No significant differences in dietary fat were seen between the Caucasian-American sample and the African-American church sample or between the two African-American samples (all Ps>.16).

Table 1.

Demographic information by group

| Caucasion (N=22)* |

University African American (N=10)* |

Church African American (N=10)* |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | |

| Age | 43.75a | (9.94) | 41.25a | (7.31) | 44.30a | (3.74) |

| Education (yrs) | 14.76a | (2.93) | 14.10a | (2.28) | 15.88a | (1.62) |

| No. children | 1.18 | (0.96)a | 0.92 | (0.67)a | 1.10 | (0.99)a |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 33.69 | (5.52) | 34.02a | (4.22) | 36.17a | (3.49) |

| kJ at baseline | 11509.07 | (2643.33) | 11166.19 | (3219.20) | 9605.19b | (3911.98) |

| % Fat at baseline | 32.83a | (9.21) | 39.67 | (7.78) | 37.64a | (5.08) |

| Income (K) | 62.4 | (19.36) | 55 | (16.24) | 67.32 | −(16.42) |

| % Employed | 86.36a | 86.36a | 90.00a | |||

| % Married | 63.63a | 66.66a | 60.00a | |||

| % Attend church | 72.72a | 83.33a | 90a | |||

BMI=body mass index; kJ at baseline=average daily kilojoule intake during baseline. Differing superscripts across rows indicate P<.05.

Some participants may have incomplete data.

Adherence

Univariate ANOVAs were used to assess the differences among groups on the two adherence measures. As indicated in Table 2, a significant difference was seen among groups on total number of sessions attended (F(3, 43)=4.46, P<.01) but not in the number of dietary records completed per week (F(3, 43) =1.42, P=.24). This later finding suggests that compliance with self-monitoring of eating was good. These results from the African-American university group are particularly noteworthy because they suggest that despite poorer in-group attendance than Caucasians, they were completing and turning in eating diaries on a regular basis. Contrasts indicated that both the Caucasian-American and the African-American church group attended significantly more sessions than the African-American university group (t(40)=2.35, P<.05; t(40)=2.85, P<.01, respectively). No differences were seen between the Caucasian-American and African-American church group in session attendance (t(40)=1.12, P=.26).

Table 2.

Treatment adherence by group

| Caucasian |

University African American |

Church African American |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | |

| # Sessions | 9.96a | (2.16) | 7.83b | (3.69) | 11.13a | (0.64) |

| # Records/week | 6.37a | (0.93) | 6.03a | (0.98) | 6.61a | (0.55) |

| Average kJ | 6333.67a | (1205.32) | 5884.13a | (1357.85) | 6256.75a | (1251.51) |

| % Fat | 22.65a | (3.67) | 25.90b | (1.08) | 28.73b | (4.76) |

Note: # Sessions=no. treatment sessions attended of 13; # Records=no. days of eating diaries per wk during treatment; average kJ=kilojoule intake during treatment; % dietary fat=avg. BMI (body mass index). Differing superscripts across rows indicate P<.05.

Weight Changes Across Treatment and Follow-Up

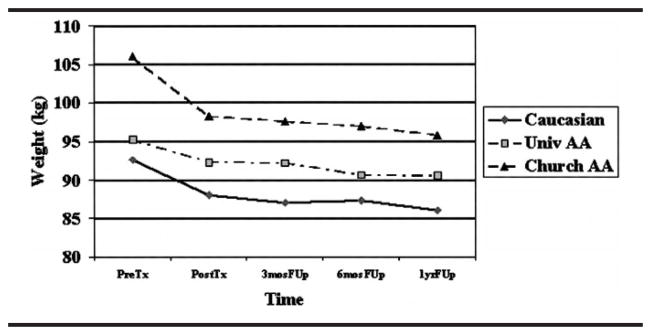

Changes in weight over time (pre-treatment, post-treatment, three-month, six-month, and one-year follow-up) are depicted in Figure 1. Univariate ANOVAs were conducted on anthropomorphic measures. Because weight change is positively associated with initial weight, pre-treatment weight was used as a covariate. Groups differed on weight loss across treatment (F(8, 160)=2.89, P<.01). Collapsing across groups, a linear trend was seen for weight to decrease over time (F(4, 160)=53.40, P<.001), and this trend can be seen in Figure 1. Controlling for initial weight, pairwise comparisons indicated that the African-American church group experienced significantly greater weight change than either university group at post-treatment and all follow-up points (all Ps<.01). The university groups did not differ from each other at any time point (all Ps>.11).

Fig 1.

Weight loss (Kg) over time by group

Percentage of dietary fat consumed during treatment differed by group (F(3, 35)=9.27, P<.01). Contrasts indicated that the Caucasian-American group consumed less dietary fat than either the African-American university group (t(38)=4.29, P<.01) or the African-American church group (t(38)=2.64, P<.05). A trend was also seen for the African-American university group to consume less dietary fat than the African-American church group (t(38)=1.81, P=.07).

Exercise Participation Across Treatment and Follow-Up

Average number of exercise sessions per week over time (pretreatment, mid-treatment, post-treatment, three-month, six-month, and one-year follow-up) are depicted in Figure 2. Similarly, Figure 3 presents average minutes exercised per session over time. During the two-week baseline, groups were exercising very little, and no differences were seen between groups in the number of exercise sessions or the number of minutes exercised. Overall, during treatment, groups did not differ in the number of times exercised per week over time or on the number of minutes exercised per week. Collapsing across groups, number of exercise sessions increased significantly from pre-treatment to mid-treatment (F(1, 39)=134.46, P<.001) and maintained at approximately 3.2–3.4 sessions per week, not differing significantly over treatment and follow-up (F(4, 39)=1.10, P>.05). No between-group differences were seen in number of exercise sessions. At post-treatment, Caucasian women reported exercising 4 times per week, which did not significantly differ from the other groups.

A significant group by time interaction was seen for minutes exercised per session (F(10, 70)=2.51, P<.05) and a significant main effect for time (F(5, 34)=31.24, P<.001). As can be seen in Figure 3, all groups evidence similar increases in exercise time from baseline to mid-treatment (F(1, 40)=66,99, P<.001) and from mid-treatment to post-treatment (F(1, 39)=12.35, P<.001). During follow up (at three months, six months, and one year), however, the groups evidence slightly different patterns (F(4, 76)=2.91, P<.05), with the Church participants maintaining or slightly increasing, the Caucasians maintaining, and the African-American university participants decreasing exercise minutes at one year. Month 12 is the only time point at which the groups significantly differed in minutes exercised (F(2, 39)=4.53, P<.05), with the church group exercising more minutes than the university African Americans.

Pre- to Post-treatment Eating and General Pathology Measures

An omnibus MANOVA conducted on measures of eating pathology and general pathology from the EI and the EDI at pre-treatment was significant (F(24, 54)=1.87, P<.05). Univariate ANOVAs indicated significant differences among groups on the hunger (F(2, 42)=4.61, P<.05) and drive for thinness (F(2, 42)=6.37, P<.01) subscales of the EI, the ineffectiveness (F(2, 42)57.67, P,.01) and interpersonal distrust (F(2, 42)=4.70, P,.05) subscales of the EDI, and the EDI total score (F(2, 42)=8.26, P<.01). As depicted in Table 3, contrasts indicated that the Caucasian-American group was more likely to overeat when hungry than either the African-American church (t(41)=2.23, P<.05) or the African-American university groups (t(41)=2.66, P<.05). No difference was seen between the African-American groups on this variable (t(41)=.07, P=.94). With respect to drive for thinness, the Caucasian-American group was significantly elevated above the African-American church group (t(41)=3.36, P<.01), but not above the African-American university group (t(41)=1.33, P=.18). Interestingly, the African-American university group also reported a higher drive for thinness than the African-American church group (t(41)=1.97, P<.05). Similarly, the contrasts on the total score of the EDI indicated that the African-American church group scored considerably lower than either the Caucasian-American (t(39)=4.06, P<.01) or African-American university groups (t(39)=2.76, P<.01). No difference was seen between these latter groups on this measure (t(39)=1.04, P=.30).

Table 3.

Eating pathology by group

| Caucasian |

University African American |

Church African American |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | |

| Eating inventory | ||||||

| Restraint | ||||||

| Pre-Tx | 9.67a | (4.91) | 9.42a | (4.17) | 6.88a | (4.09) |

| Post-Tx | 8.68a | (3.66) | 9.62a | (4.03) | 11.55a | (3.00) |

| Disinhibition | ||||||

| Pre-Tx | 10.27a | (3.08) | 8.46ab | (4.42) | 7.25b | (3.69) |

| Post-Tx | 5.13a | (3.42) | 3.12a | (3.09) | 3.33a | (1.00) |

| Hunger | ||||||

| Pre-Tx | 8.17a | (3.76) | 4.97b | (3.08) | 5.08b | (2.48) |

| Post-Tx | 4.54a | (2.72) | 2.87a | (2.35) | 3.11a | (1.76) |

| Eating disorders inventory | ||||||

| Drive for thinness | ||||||

| Pre-Tx | 6.96a | (4.26) | 5.17a | (3.71) | 1.75b | (1.67) |

| Post-Tx | 5.31a | (5.38) | 3.66a | (4.53) | 1.66a | (2.54) |

| Bulimia | ||||||

| Pre-Tx | 3.04a | (3.10) | 1.33a | (1.23) | 1.50a | (1.41) |

| Post-Tx | 1.09a | (2.11) | 1.11a | (2.26) | 0.00 | (0.00) |

| Body dissatisfaction | ||||||

| Pre-Tx | 15.92a | (6.55) | 12.75a | (6.73) | 13.38a | (4.31) |

| Post-Tx | 16.68a | (8.17) | 15.11a | (10.10) | 9.62b | (6.32) |

| Internal awareness | ||||||

| Pre-Tx | 4.21a | (4.45) | 2.5ab | (2.32) | 1.38b | (1.51) |

| Post-Tx | 3.68a | (2.45) | 2.11a | (2.97) | 0.62b | (1.76) |

| Ineffective | ||||||

| Pre-Tx | 5.75a | (4.26) | 5.92a | (4.60) | .25b | (0.46) |

| Post-Tx | 1.13a | (1.67) | 1.88a | (3.29) | 0 | (0.00) |

| Distrust | ||||||

| Pre-Tx | 6.54a | (3.99) | 8.42a | (5.00) | 3.75a | (2.60) |

| Post-Tx | 1.18a | 1.89 | .66a | 0.86 | 1.50a | −2.32 |

Differing superscripts across rows indicate P<.05.

Additional contrasts indicated that the African-American church group reported less disinhibition (t(41)=2.06, P<.05) than the Caucasian-American group. The African-American church group also reported less ineffectiveness than both the Caucasian-American (t(41)=3.38, P<.01) and African-American university groups (t(41)=3.11, P<.01), less interpersonal distrust than the Caucasian-American (t(41)=2.27, P<.05) and the African-American university groups (t(41)=2.72, P<.05), and less internal awareness than the Caucasian-American group (t(41)=2.69, P<.05). All other pairwise comparisons were nonsignificant (all Ps>.14).

To examine the change across treatment, a series of repeated group X time MANOVAs were conducted. Results indicated a significant group X time interaction on the restraint (F(2, 34)=3.93, P<.05) and disinhibition subscales of the EDI (F(2, 34)=3.74, P<.05). There was also a trend towards a significant group X time interaction on the ineffectiveness (F(2, 35)=3.02, P=.06) and interpersonal distrust subscales of the EDI (F(2, 35)=2.91, P=.06). To aid in understanding the nature of the interactions, a series of repeated measures ANOVAs were conducted on each variable for each group individually. Results from the restraint subscale indicated that the African-American church group evidenced a significant increase from pre- to post-treatment (F(1, 7)=8.44, P<.05), while the Caucasian-American and African-American university group did not (all Ps>.17). Conversely, the analysis from the disinhibition subscale indicated that the Caucasian-American (F(1, 20)=94.26, P<.01) and African-American university groups (F(1, 7)=16.21, P<.01) significantly decreased, while the African-American church group only evidenced a trend in that direction (F(1, 7)=4.95, P=.06). The results from the ineffectiveness subscale of the EDI indicated that only the Caucasian-American group evidenced a significant decrease (F(1, 21)=30.64, P<.01), while the two African-American groups did not (all Ps>.13). While all groups evidenced a significant decrease in interpersonal distrust (all Ps<.05), an examination of the means in Table 3 indicates that the Caucasian-American group evidenced the greatest decrease across treatment on this variable. Baseline distrust was low for the church members.

In addition, repeated measures MANOVAs indicated a significant effect for time on the hunger (F(1, 33)=17.24, P<.01), EDI total score (F(1, 30)=8.45, P<.01), and the maturity fears subscales of the EDI (F(1, 34)=6.02, P<.05), suggesting that each group experienced a comparable reduction in the respective subscales. There was also a trend toward significance across time on the bulimia subscale (F(1, 33)=3.52), P=.06). No significant main effect or interaction was found on the drive for thinness, body dissatisfaction, internal awareness, or perfectionism subscales of the EDI (all Ps>.18). Follow-up contrasts at post-treatment indicated that the African-American church group was significantly lower on the body dissatisfaction (t(36)=2.05, P<.05), EDI total score (t(36)=2.35, P<.05), and internal awareness (t(36)=2.99, P<.01) subscales of the EDI.

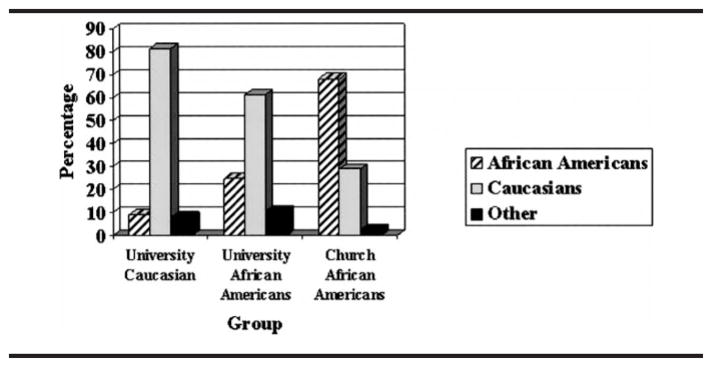

Accounting for Differences in Eating Pathology

Following from the conceptualization of Carter, Sbrocco, and Carter regarding the importance of acculturation in the manifestation and presentation of psychopathology, we sought to examine the ethnic composition of study participants’ neighborhoods post-hoc.19 Given that no group differences were found for some of the major demographic variables including age, household income, and education, it seemed reasonable to examine this demographic variable reasoning that African Americans who lived in predominately African-American neighborhoods would be less likely to hold the Caucasian ideals that are associated with problem eating attitudes and behaviors. Of note, self-report measures of acculturation (eg, AAAS)43 would provide a direct index of this construct and could be used in future studies. Census data were obtained by using participants’ addresses to determine the corresponding Census tract. The MapInfo computer program provided coordinates of each participant’s census tract.44 Ethnic composition is presented for each group in Figure 4. As expected, the ethnic composition of the groups did differ, with the church group living in predominately African-American neighborhoods, the Caucasian Americans living in predominately Caucasian neighborhoods, and the university African Americans living in more diverse or “mixed” neighborhoods.

Fig 4.

Ethnic composition of neighborhood by group

Discussion

The major findings of interest in this study were the differences in adherence by site for the African-American participants and the differing eating pathologies across all groups. These preliminary findings provide more suggestions than they do answers for research examining factors that impact treatment adherence and the expression of eating attitudes and behaviors, particularly because this study did not randomly assign participants to groups but used samples of convenience that represented existing treatment delivery settings.

Factors Impacting Treatment for Ethnic Minorities

The fields of psychology and medicine are increasingly recognizing the need to address culture in developing and delivering effective treatments.20,21,47 This study suggests that factors such as group composition may be important to examine when evaluating the efficacy of a treatment. While this study noted poorer attendance among the ethnic minority group when they were in the minority, other studies using group treatment for other problems have suggested that whoever is in the minority may be less likely to participate.45,46 In the current study, we cannot determine whether the church-based group was effective because it was all African American, was conducted at a church, may have shared social support, or some combination of such factors. Controlling such variables through random assignment of individuals to groups of same- or mixed-ethnicity groups and also examining the impact of church or community settings vs university based settings should be carefully addressed in future studies. Also important would be to compare church-based groups that share some demographics (eg, age, income) but differ in where they live. Thus, the major limitation of this study is the lack of random assignment to groups. The study was conducted with samples of convenience. However, given the striking differences in the results, examining such quasi-experimental findings is important to develop more tightly controlled designs that allow for more definitive answers.

The differences in eating pathology and eating behavior suggest a point of major interest. The two African-American groups differed from each other on measures of eating pathology, despite not differing on major demographic variables such as education and household income. Similarly, the church-based group ate higher-fat diets and exercised less. This finding may account for the fact that they reported eating less (baseline kilojoules) than the other groups. They did differ in the ethnic composition of their neighborhoods. Such results suggest the importance of using measures of culture and acculturation rather than relying simply on self-identified ethnicity. Such measures may elucidate the fact that all African Americans are not alike. For example, while African-American women and girls have been considered to have greater body acceptance and perceive themselves as less overweight,47,48 increased levels of acculturation in ethnic minority groups have been negatively correlated with this increased body acceptance.49,50

With the push to develop efficacious treatments, we must address such issues as minority response, effectiveness with different minority groups, and settings in which treatments are used and well-received. These issues have been identified with regard to evaluating nutritional interventions and African Americans, yet little empiric work has been done.21,22,26 Despite increasing diversity, the differences between cultures are often difficult to recognize by members of the “other” group. Consequently, scientists and practitioners may attribute differences to personal characteristics (eg, African Americans drop out of treatment) without understanding other factors that may be at work (eg, African Americans may be uncomfortable in predominately Caucasian groups or may be unable to relate to Caucasian Americans with differing eating attitudes). As we work to develop effective treatments, we must take a step back and consider other variables and influences that may impact treatment delivery, adherence, and acceptability.

Eating Patterns and Weight Change

The present study presents important data documenting continuing weight loss and weight maintenance with BCT, a type of treatment that is designed to promote slow, maintainable weight loss that continues over time. Another important finding for all groups is the consistency in exercise over time. A number of other methodologic issues limit the findings of this study. The sample size is small. The study is also limited by the population studied, which included middle class, well-educated, moderately obese women. In summary, many questions remain unanswered, yet the continuing weight loss observed does offer promise for improving obesity treatment. Given the widespread problem of obesity, the paucity of data on African-American women, and the difficulty in maintaining weight loss, these preliminary findings are clearly worthy of further investigation.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by R01 DK 55469 and USUHS TO72. We acknowledge Jay M. Stone, PhD, Randall C. Nedegaard, PhD, and Elena Fichera for their help.

Footnotes

Author’s note: The opinions or assertions contained herein are the private ones of the authors and are not to be construed as official or reflecting the views of the US Department of Defense or USUHS.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Design and concept of study: Sbrocco, Carter, Lewis, Vaughn, Kalupa, Suchday

Acquisition of data: Sbrocco, Vaughn, Kalupa, Cintron

Data analysis and interpretation: Sbrocco, Carter, Kalupa, Suchday, Osborn

Manuscript draft: Sbrocco, Carter, Lewis, Vaughn, Kalupa, Osborn, Cintron

Statistical expertise: Sbrocco, Carter, Suchday

Acquisition of funding: Sbrocco

Administrative, technical, or material assistance: Sbrocco, Lewis, Vaughn, Kalupa, Osborn, Cintron

Supervision: Sbrocco, Carter, Lewis

References

- 1.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) . Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults. Washington, DC: NHLBI; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2000. JAMA. 2002;288(14):1723–1727. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuczmarski RJ, Flegal KM, Campbell SM, Johnson CL. Increasing prevalence of overweight among US adults. JAMA. 1994;272:205–211. doi: 10.1001/jama.272.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Health, United States. Table 70: Healthy Weight, Overweight, and Obesity Among Persons 20 Years of Age and Over, According to Sex, Age, Race, and Hispanic Origin: United States, 1960–62, 1971–74, 1976–80, 1988–94, and 1999–2000. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steffen PR, Sherwood A, Gullette CD, Georgiades A, Hinderliter A, Blumenthal JA. Effects of exercise and weight loss on blood pressure during daily life. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(10):1635–1640. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200110000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schotte DE, Stunkard AJ. The effects of weight reduction on blood pressure in 301 obese patients. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:1701–1704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wing RR, Epstein LH, Nowalk MP, Scott N, et al. Family history of diabetes and its effect on treatment outcome in type II diabetes. Behav Ther. 1987;18(3):283–289. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brownell KD, Rodin J. The dieting maelstrom: is it possible and advisable to lose weight? Am Psychol. 1994;49:781–791. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.49.9.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garner DM, Wooley SC. Confronting the failure of behavioral and dietary treatments for obesity. Clin Psychol Rev. 1991;11:729–780. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glenny AM, O’Meara S, Melville A, Sheldon TA, Wilson C. The treatment and prevention of obesity: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Obes. 1997;21:715–737. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perri MG. The maintenance of treatment effects in the long-term management of obesity. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 1998;5(4):526–543. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ciliska D. Beyond dieting: psychoeducational interventions for chronically obese women: a non-dieting approach. In: Garfinkel PE, Garner DM, editors. Eating Disorders Monograph Series No. 5. New York, NY: Brunner/Mazel; [Google Scholar]

- 13.Polivy J, Herman CP. Undieting: a program to help people stop dieting. Int J Eat Disord. 1992;11:261–268. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sbrocco T, Nedegaard RC, Stone JM, Lewis EL. Behavioral Choice Treatment promotes continuing weight loss: preliminary results of a cognitive-behavioral decision-based treatment for obesity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:260–266. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.2.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sbrocco T, Lewis E, Stone J, Nedegaard R, Kalupa K, Vaughn N. Behavior choice promotes continuing weight loss: two year follow up. Ann Behav Med. 2001;23(suppl):S055. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sbrocco T, Kalupa K, Vaughn N, Stone J, Lewis E. Understanding eating behavior: difference in behavioral choices and outcomes for obese and normal weight women. Ann Behav Med. 2001;23(suppl):S027. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tyler DO, Allan JD, Alcozer FR. Weight loss methods used by African-American and Euro-American women. Res Nurs Health. 1997;20:413–423. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199710)20:5<413::aid-nur5>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walcott-McQuigg JA, Logan B, Smith E. Preventive health practices of African-American women. J Natl Black Nurses Assoc. 1994;7(2):49–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carter MM, Sbrocco T, Carter C. African Americans and anxiety disorders research: development of a testable theoretical framework. Psychother Theory Res Pract. 1996;33:449–463. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumanyika SK, Obarzanek E, Stevens VJ, Hebert PR, Whelton PK. Weight-loss experience of Black and Caucasian participants in NHLBI-sponsored clinical trials. Clin Nutr. 1991;53:1631–1638. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/53.6.1631S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumanyika SK, Morssink C, Agurs T. Models for dietary and weight change in African-American women: identifying cultural components. Ethn Dis. 1992;2:166–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanders BS, Ullmann-Joy P, Foreyt JP, et al. The Black American lifestyle intervention (BALI): the design of a weight loss program for working-class African-American women. J Am Diet Assoc. 1994;94(3):310–312. doi: 10.1016/0002-8223(94)90374-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McNabb W, Quinn M, Kerver J, Cook S, Karrison T. The PATHWAYS church-based weight loss program for urban African-American women at risk for diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:1518–1523. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.10.1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumanyika SK, Charleston JB. Lose weight and win: a church-based weight loss program for blood pressure control among Black women. Patient Educ Couns. 1992;19(1):19–32. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(92)90099-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sutherland MS, Hale CD, Harris GJ. Community health promotion: the church as a partner. J Primary Prev. 1995;16(2):201–216. doi: 10.1007/BF02407340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumanyika SK, Morssink CB. Cultural appropriateness of weight management programs. In: Dalton S, editor. Overweight and Weight Management: The Health Professional’s Guide to Understanding and Practice. Gaithersburg, Md: Aspen Publishers; 1997. pp. 69–103. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hatch JW, Lovelace KA. Involving the Southern rural church and students of the health professions in health education. Public Health Rep. 1980;95:23–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olson LM, Reis J, Murphy L, Gehm JH. The religious community as a partner in health care. J Community Health. 1988;13:249–257. doi: 10.1007/BF01324237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee R, McGinnis K, Sallis J, Castro CM, Chen AH, Hickmann SA. Active vs passive methods of recruiting ethnic minority women to a health promotion program. Ann Behav Med. 1997;19(4):378–384. doi: 10.1007/BF02895157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davis NL, Clance PR, Gailis AT. Treatment approaches for obese and overweight African-American women: a consideration of cultural dimensions. Psychotherapy. 1999;36(1):27–35. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baldwin KA, Humbles PL, Armmer FA, Cramer M. Perceived health needs of urban African-American church congregants. Public Health Nurs. 2001;18(5):295–303. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2001.00295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walls CT, Zarit SH. Informal support from Black churches and the well-being of elderly Blacks. Gerontologist. 1991;31(4):490–495. doi: 10.1093/geront/31.4.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Metropolitan Life Insurance Company. Metropolitan height and weight standards. Stat Bull of New York Metropolitan Life Insurance Company. 1983;64:2–9. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schlundt DG, Hill JO, Sbrocco T, Pope-Cordle J, Kasser T, Sharp T. The role of breakfast in the treatment of obesity: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992;55:645–651. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/55.3.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hill JO, Schlundt DG, Sbrocco T, et al. Weight reduction in obese women: effects of alternating calories and exercise. Am J Clin Nutr. 1989;50:248–254. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/50.2.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Streit KJ, Stevens NH, Stevens VJ, Rossner J. Food records: a predictor and modifier of weight change in a long term weight loss program. J Am Diet Assoc. 1991;91:213–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Psion PLC. London, England: Psion PLC; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sbrocco T, Stone JM, Nedegaard RC, Lewis EL, Patel K, Gallant L. Use of palmtop computers to assess dietary intake: a comparison of obese and normal weight women. In press. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Compute-A-Diet Nutrient Balance System [computer software] Worcestershire, England: Comcard Ltd; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stunkard AJ, Messick S. The Eating Inventory. San Antonio, Tex: Psychological Corporation; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garner DM. The Eating Disorder Inventory-2 Professional Manual. Odessa, Fla: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Allison DB. Handbook of Assessment Methods for Eating Behaviors and Weight Related Problems: Measures, Theory, and Research. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publication; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Landrine H, Klonoff EA. The African-American Acculturation Scale: development, reliability, and validity. J Black Psychol. 1994;20(2):104–127. [Google Scholar]

- 44.MapInfo Professional. User’s Guide. Troy, NY: MapInfo Corporation; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saunders DG, Parker JC. Legal sanctions and treatment follow-through among men who batter: a multivariate analysis. Soc Work Res Abstracts. 1989;25(3):21–29. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hamberger LK, Hastings JE. Counseling male spouse abusers: characteristics of treatment completers and dropouts. Violence Vict. 1989;4(4):275–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kumanyika SK. Obesity in minority populations: an epidemiologic assessment. Obes Res. 1994;2:166–182. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1994.tb00644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Story M, French SA, Resnick MD, Blum RW. Ethnic/racial and socioeconomic differences in dieting behaviors and body image perceptions in adolescents. Int J Eat Disord. 1995;18:173–179. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199509)18:2<173::aid-eat2260180210>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mennen LI, Jackson M, Cade J, et al. Underreporting of energy intake in four populations of African origin. Int J Obes. 2000;24:882–887. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mastria MR. Ethnicity and eating disorders. Psychoanal Psychother. 2002;19(1):59–77. [Google Scholar]