Abstract

Background

Cytoreductive surgery (CS) with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) is the treatment most likely to achieve prolonged survival in peritoneal carcinomatosis (PC). Yet the efficacy of HIPEC in rectal patients is controversial because of the retroperitoneal location of the primary tumor. Therefore, we reviewed our experience in patients with PC from a rectal primary tumor.

Methods

A retrospective analysis of a prospective database of 950 HIPEC procedures was performed. Performance status, age, albumin level, prior surgical score, resection status, morbidity, mortality, and survival were reviewed.

Results

A total of 13 and 204 patients with PC from rectal and colon cancer, respectively, were identified. Median follow-up was 40.1 and 88.1 months, respectively. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) score was zero or one for 92 % of patients with rectal cancer and 83 % for colon, while R1 resection was achieved in 54 and 51 %. The 30-day mortality was 5 % for colon cancer. There were no deaths in the rectal group. The morbidity for the colon and rectal groups was 57 and 46 %, respectively, with a 23 % 30-day readmission rate. In univariate analysis, age, ECOG, prior surgical score, albumin level, and node and resection status were not statistically significant in predicting survival for the rectal cancer patients. Median survival for the rectal and colon groups was 14.6 versus 17.3 months, while the 3-year survival was 28.2 versus 25.1 %.

Conclusions

Our data demonstrate similar 3-year survival for patients with rectal and colon cancer PC treated with CS/HIPEC. This can be attributed to patient selection bias. Selected rectal cancer PC patients should not be excluded from an attempted cytoreduction and HIPEC.

Over the last 20 years, cytoreductive surgery (CS) with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) has slowly emerged as an effective treatment modality for patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis (PC) from colorectal cancer. A prospective randomized trial with 8 years of follow-up demonstrated a 45 % 5-year survival in patients with PC, mainly of colorectal primary tumors.1 Several authors have reported similar retrospective outcomes from both single-institution and multi-institutional studies.2–4 Currently, PC from colon and rectal primary cancer is studied together under the term “colorectal” in the same way that in the past appendiceal cancer was incorporated into the colon cancer cohorts. We know today from both genetic analysis and clinical outcome studies that PC from appendiceal and colon cancer represent two distinct entities with completely different biologic behaviors and prognoses.5

We currently accept that HIPEC treats peritoneal surface disease. Therefore, we wondered what the role was of a HIPEC procedure in treating PC from rectal cancer that originates anatomically below the peritoneal reflection, and whether the efficacy of HIPEC treatment was similar for rectal and colon primary tumors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a retrospective analysis of a prospectively maintained database of 950 CS/HIPEC procedures. Institutional review board approval was obtained for this study.

Patient data relevant to our analysis included age, gender, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) graded performance status, date of CS/HIPEC, chemoperfusion agent, R status of resection, type of malignancy, nodal status of disease, prior surgical score (PSS), morbidity, mortality, and median survival.6 Eligibility criteria for CS/HIPEC were ECOG score of ≤3, histologic or cytologic diagnosis of PC, and complete recovery from prior systemic chemotherapy or radiation treatments, resectable or resected primary lesion, debulkable peritoneal disease, no extra-abdominal disease, and limited medical comorbidities. All patients had a complete history and physical, tumor markers, and CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis before all CS/HIPEC procedures. The HIPEC procedure was conducted as previously described by our group.7

Descriptive statistics, including means and standard deviations for continuous data and frequencies and percentages for categorical data, were calculated. Fisher's exact tests were used to detect statistically significant differences for categorical variables. Survival from the date of surgery to last know date of follow-up or death was assessed by the Kaplan–Meier method, and log rank tests were used to test significance between groups. A multivariate analysis of predictors of death from colorectal cancer was performed by Cox proportional hazard regression. All analyses were performed by SAS 9.2 (SAS, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

From 1993 to 2011, a total of 950 CS/HIPEC procedures for isolated peritoneal surface disease were performed at our institution. Of these 950 procedures, 223 were performed for 217 patients to treat PC from colorectal origin. The colorectal group included 204 patients who had cytoreductions for colon primary PC and 13 for rectal primary tumor. The colon and rectal groups were similar, with the exception of follow-up length and PSS (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Colon and rectum cohort characteristics

| Characteristic | Colon (n = 204) | Rectum (n = 13) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.15 | ||

| Female | 92 (45.1 %) | 3 (23.1 %) | |

| Male | 112 (54.9 %) | 10 (76.9 %) | |

| Age (year) mean (SD) | 53.2 (12.9 %) | 48.8 (11.1 %) | 0.18 |

| ECOG | 0.70 | ||

| 0/1 | 169 (82.8 %) | 12 (92.3 %) | |

| 2+ | 32 (15.7 %) | 1 (7.7 %) | |

| R status | 1.00 | ||

| R0/1 | 103 (50.5 %) | 7 (53.8 %) | |

| R2 | 101 (49.5 %) | 6 (46.2 %) | |

| Readmit | 1.00 | ||

| No | 157 (77.0 %) | 10 (76.9 %) | |

| Yes | 47 (23.0 %) | 3 (23.1 %) | |

| Prior surgical score | 0.009 | ||

| 0 | 15 (7.4 %) | 5 (38.5 %) | |

| 1 | 78 (38.2 %) | 3 (23.1 %) | |

| 2+ | 93 (45.6 %) | 5 (38.5 %) | |

| Node status | 1.00 | ||

| Positive | 134 (66.7 %) | 8 (66.7 %) | |

| Negative | 67 (33.3 %) | 4 (33.3 %) | |

| Albumin (g/dl), mean (range) | 3.7 (2.0–4.9) | 3.8 (1.6–4.8) | 0.60 |

| Complications | 0.57 | ||

| No | 87 (42.6 %) | 7 (53.8 %) | |

| Yes | 117 (57.4 %) | 6 (46.2 %) | |

| 30-day mortality | – | ||

| No | 193 (94.6 %) | 13 (100.0 %) | |

| Yes | 11 (5.4 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | |

| Long-term mortality | – | ||

| No | 47 (23.0 %) | 6 (46.2 %) | |

| Yes | 157 (77.0 %) | 7 (53.8 %) | |

| Median follow-up (months) | 88.1 | 40.1 | 0.01 |

| Median survival (months) | 17.3 | 14.6 | – |

ECOG Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

Data are presented as n (%) unless otherwise indicated

Median follow-up was 40.1 months for the rectal group and 88.1 months for the colon group (p = 0.01). This difference in follow-up is due to two factors. First, six (75 %) of eight node-positive rectal patients died within 18 months of the operation. Second, 62 % (eight of 13) of the procedures were performed during the last 3 years of the study. The PSS score was higher for the rectal group as a result of prior surgical exploration or resection (p = 0.009).

Disease Presentation, History of Treatment, and Organs Resected During Cytoreduction

Eight rectal patients (62 %) presented with synchronous disease in the rectum and peritoneal cavity. Only 50 % (four of eight) of these patients had CS/HIPEC as their first surgical intervention. The remaining 50 % had prior surgical exploration and resection. Eleven patients (85 %) received preoperative chemotherapy and eight patients (62 %) received radiation before CS/HIPEC. The organs resected during the CS/HIPEC procedures are listed in Table 2 to demonstrate a rough approximation of the volume of disease.

TABLE 2.

Resected organs during cytoreduction of rectal peritoneal carcinomatosis

| Organ | % |

|---|---|

| Omentum | 54 |

| Small bowel | 54 |

| Colon | 38 |

| Rectum | 31 |

| Gallbladder | 15 |

| Liver | 15 |

| Spleen | 8 |

| Uterus | 8 |

| Ovary | 8 |

| Diaphragm | 8 |

| Appendix | 15 |

| Stomach | 0 |

ECOG Performance Status, Resection Status, Nodal Status, and PSS

An ECOG performance status of zero or one was similar for the rectal and colon groups (92 vs. 83 %, p = 0.70). Complete cytoreduction (R0/R1) was achieved in 54 % of the rectal group and in 51 % of the colon group (p = 1.0). Positive regional or distant lymph nodes at the time of primary tumor resection or CS/HIPEC were found in 33 % of both the rectal and colon patients (p = 1.0). The majority of the rectal group (eight of 13, 62 %) had either no prior dissection (PSS 0) or laparotomy with one region dissected by the referring surgeon (PSS 1).

Postoperative Morbidity and Mortality

Postoperative morbidity was similar in rectal and colon patients (51 vs. 46 %, p = 0.78). Minor complications (Clavien-Dindo grades I/II) occurred in 31 % of rectal patients and 33 % of colon patients, while major complications (Clavien-Dindo grades III/IV) occurred in 15 and 18 %, respectively.8 The 30-day readmission rate was 23 % in both groups. Operative mortality was 0 % for the rectal group and 5.7 % for the colon group (p = 1.0).

Survival and Prognostic Factors

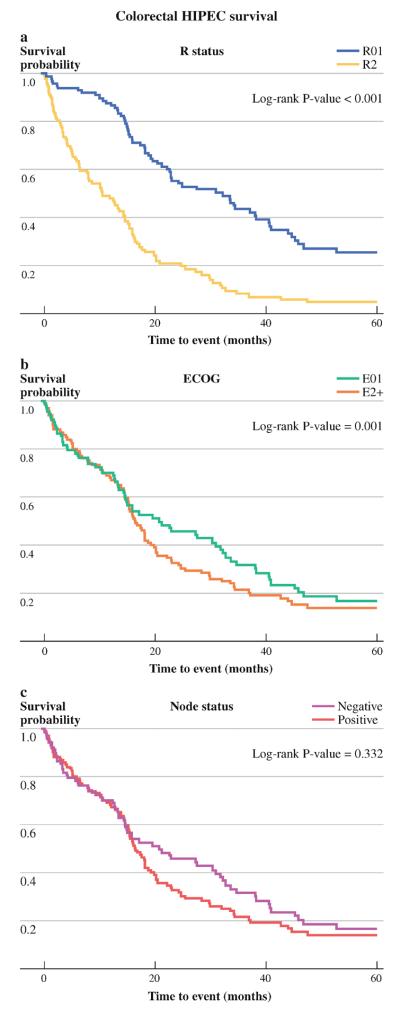

Resection status and the ECOG performance status were strong prognosticators of improved survival in the colorectal group, with R0/R1 resection (p = 0.001) and ECOG 0/1 (p = 0.001) patients doing better (Fig. 1a, b). However, nodal status was not prognostic for survival (p = 0.21) in the colorectal cohort (Fig. 1c).

FIG. 1.

Survival of colorectal cohort based on a R status of resection, b ECOG performance status, and c nodal status

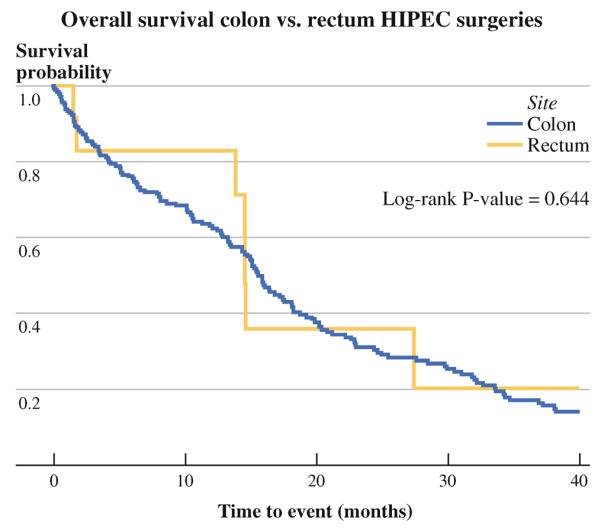

Median survival was 14.6 months for the rectal group and 17.3 months for the colon group; 3-year survival was 28.2 and 25.1 %, respectively (log rank p = 0.644) (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Survival curves for rectum versus colon cohorts

In univariate analysis, age (p = 0.2735), albumin (p = 0.09), PSS (p = 0.93), cytoreduction completeness (p = 0.11), ECOG performance status (p = 0.28), and nodal status (p = 0.09) were not statistically significant in predicting survival of rectal cancer patients.

There were no long-term survivors for rectal PC patients who had an incomplete cytoreduction.

At the time of analysis, only one of eight node-positive rectal PC patients remained alive at 40 months, while all node-negative patients were still alive. PSS was not significant for both rectal and colorectal groups in predicting survival (log rank p = 0.891).

DISCUSSION

CS/HIPEC is the treatment most likely to achieve prolonged survival in peritoneal surface disease from colorectal primary tumor. Colon and rectal cases have been bundled together even though the number of rectal cancer-induced PC is small and disproportionally low in terms of the actual incidence of rectal cancer. More specifically, rectal cancer represents 28 % of the new colorectal cases, while the number of rectal PC patients treated with CS/HIPEC in the reported literature ranges between 7 and 17 %.2,4,9–11 This may reflect different biological behavior and/or variations in referral patterns.

Our analysis revealed similar survival for the rectal and colon cancer PC patients treated with CS/HIPEC. Therefore, one question needed to be addressed: who is the optimal rectal PC candidate to undergo a CS/HIPEC procedure? To answer this question, we examined our data in several different ways.

We looked at the effect of the nodal status on survival. Only one out of eight rectal PC patients who had positive lymph node status was alive at 40 months; this was not statistically significant. Therefore, we looked at the significance of node status on the entire colorectal cohort. Surprisingly, there was no statistical significance in the survival between node-positive and node-negative colorectal patients. This is in contrast to what other authors have reported.2,4,10 We then examined the importance of nodal status only in the group of patients who had a complete cytoreduction. Again, there was no statistical significance in the survival between node-positive colon and node-positive rectal patients who had a complete cytoreduction, emphasizing the higher importance of removing the entire bulk of disease over the metastatic potential of the tumor.10 Despite the lack of statistical significance, we are concerned that the node-positive rectal group indeed represents a group that will do poorly with CS/HIPEC and should be treated with caution.

We selected patients for the operation on the basis of both the location and total volume of disease. Disease in the porta hepatis or around the major abdominal vasculature will exclude patients from the operation. In the same context, a PC index value of >20 makes us reluctant to proceed with exploration.2 Furthermore, we consider multistation bowel obstruction, bilateral ureteral obstruction, and biliary obstruction to be contraindications.

Preoperative albumin levels in our colorectal and rectal patients were not predictive for survival by univariate or multivariate analysis. Albumin is a well-documented risk factor of operative morbidity and mortality in cohorts that contain surgical patients from a variety of surgical sub-specialties and types of disease.12 The presented cohort includes only patients with PC where possibly the impact of the disease on long-term survival is more prominent than the impact of their preoperative nutritional status. In addition, because many of our patients are malnourished as a result of malignancy and prior therapies, great effort is made to improve their nutritional status before surgery by providing enteral supplementation or parenteral nutrition when indicated. From this perspective, we regard albumin as a prognosticator of postoperative complications rather than as a prognosticator of survival, with the exception of the elderly population, where albumin does play a role in predicting survival, possibly because a postoperative complication in elderly is much less tolerable.13

Several authors have reported the importance of completion of the cytoreduction and functional status in the survival of patients with PC from colorectal cancer undergoing CS/HIPEC.2,14–18 Data from our cohort of colorectal PC patients agreed with these reports. The colorectal PC patients most likely to have prolonged survival are those who had a complete cytoreduction and had maintained their functional status before the operation. The same was true for PC from rectal cancer. There were no long-term survivors past 27 months in patients with incomplete cytoreduction or with an ECOG functional status of >1. The importance of completeness of cytoreduction has its own implications. For example, one of the most challenging anatomic locations to achieve complete cytoreduction is the pelvis. Exposed retroperitoneum from prior resection causes iatrogenic tumor seeding and adhesions, which increase the chance of converting simple peritoneal stripping to inoperable disease with involvement of ureters and iliac vessels. This is important for patients that present with synchronous rectal and peritoneal disease. These patients should be referred directly to a peritoneal surface disease center, and a staged resection should not be attempted at the referring institution.

The major limitation of this study is that it is a single-institution retrospective review, where patients were selected on the basis of our more than 20 years' experience. Therefore, selection bias is inevitably a factor in patient enrollment. The number of rectal patients is small but still toward the high end of what is available in the published literature. The scarcity of these patients and the lack of confidence in nonrandomized multi-institutional trials emphasize the future need of relating gene-expression profiling to patient selection.5

In conclusion, we were not able to demonstrate a survival difference between rectal and colon cancer PC patients treated with CS/HIPEC. It seems that the location of the primary tumor in the rectum does not influence survival outcomes for patients who have metastatic disease confined in the peritoneal cavity. Therefore, the survival benefit depends on the ability to perform a complete cytoreduction and on the biological behavior of the tumor. The location of the primary tumor has no impact on survival, as long as all macroscopic disease can be removed. Rectal PC patients with low-volume disease, preserved functional status, and negative nodes have improved survival;; although this did not reach statistical significance, these patients are likely to have superior outcomes. On the basis of our analysis, selected rectal cancer PC should not be excluded from attempted cytoreduction and HIPEC.

REFERENCES

- 1.Verwaal VJ, Bruin S, Boot H, van Slooten G, van Tinteren H. 8-Year follow-upofrandomizedtrial:cytoreductionandhyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy versus systemic chemotherapy in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:2426–32. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-9966-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.da Silva RG, Sugarbaker PH. Analysis of prognostic factors in seventy patients having a complete cytoreduction plus perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy for carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203:878–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elias D, Lefevre JH, Chevalier J, Brouquet A, Marchal F, Classe JM, et al. Complete cytoreductive surgery plus intraperitoneal chemohyperthermia with oxaliplatin for peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal origin. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:681–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.7160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elias D, Gilly F, Boutitie F, Quenet F, Bereder JM, Mansvelt B, et al. Peritoneal colorectal carcinomatosis treated with surgery and perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy: retrospective analysis of 523 patients from a multicentric French study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:63–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.9285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levine EA, Blazer DG, III, Kim MK, Shen P, Stewart JH, Guy C, et al. Gene expression profiling of peritoneal metastases from appendiceal and colon cancer demonstrates unique biologic signatures and predicts patient outcomes. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214:599–606. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacquet P, Sugarbaker PH. Clinical research methodologies in diagnosis and staging of patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis. Cancer Treat Res. 1996;82:359–74. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-1247-5_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shen P, Stewart JH, Levine EA. Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for peritoneal surface malignancy: overview and rationale. Curr Probl Cancer. 2009;33:125–41. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–13. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glehen O, Kwiatkowski F, Sugarbaker PH, Elias D, Levine EA, De Simone M, et al. Cytoreductive surgery combined with perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy for the management of peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer: a multi-institutional study. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3284–92. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verwaal VJ, van Ruth S, de Bree E, van Sloothen GW, van Tinteren H, Boot H, et al. Randomized trial ofcytoreductionand hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy versus systemic chemotherapy and palliative surgery in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3737–43. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibbs J, Cull W, Henderson W, Daley J, Hur K, Khuri SF. Preoperative serum albumin level as a predictor of operative mortality and morbidity: results from the national VA surgical risk study. Arch Surg. 1999;134:36–42. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.134.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Votanopoulos KI, NNCSPSJRGL Cytoreductive surgery (CRS) with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) in the elderly. Presented at society of surgical oncology 65th annual meeting; Orlando: SSO; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elias D, Blot F, El Otmany A, Antoun S, Lasser P, Boige V, et al. Curative treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis arising from colorectal cancer by complete resection and intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Cancer. 2001;92:71–6. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010701)92:1<71::aid-cncr1293>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glehen O, Cotte E, Schreiber V, Sayag-Beaujard AC, Vignal J, Gilly FN. Intraperitoneal chemohyperthermia and attempted cytoreductive surgery in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal origin. Br J Surg. 2004;91:747–54. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ihemelandu CU, Shen P, Stewart JH, Votanopoulos K, Levine EA. Management of peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer. Semin Oncol. 2011;38:568–75. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McQuellon RP, Loggie BW, Lehman AB, Russell GB, Fleming RA, Shen P, et al. Long-term survivorship and quality of life after cytoreductive surgery plus intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy for peritoneal carcinomatosis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:155–62. doi: 10.1245/aso.2003.03.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shen P, Hawksworth J, Lovato J, Loggie BW, Geisinger KR, Fleming RA, et al. Cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy with mitomycin C for peritoneal carcinomatosis from nonappendiceal colorectal carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:178–86. doi: 10.1245/aso.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]