Abstract

Aims: The intracellular pathogen Burkholderia pseudomallei causes the disease melioidosis, a major source of morbidity and mortality in southeast Asia and northern Australia. The need to develop novel antimicrobials is compounded by the absence of a licensed vaccine and the bacterium's resistance to multiple antibiotics. In a number of clinically relevant Gram-negative pathogens, DsbA is the primary disulfide oxidoreductase responsible for catalyzing the formation of disulfide bonds in secreted and membrane-associated proteins. In this study, a putative B. pseudomallei dsbA gene was evaluated functionally and structurally and its contribution to infection assessed. Results: Biochemical studies confirmed the dsbA gene encodes a protein disulfide oxidoreductase. A dsbA deletion strain of B. pseudomallei was attenuated in both macrophages and a BALB/c mouse model of infection and displayed pleiotropic phenotypes that included defects in both secretion and motility. The 1.9 Å resolution crystal structure of BpsDsbA revealed differences from the classic member of this family Escherichia coli DsbA, in particular within the region surrounding the active site disulfide where EcDsbA engages with its partner protein E. coli DsbB, indicating that the interaction of BpsDsbA with its proposed partner BpsDsbB may be distinct from that of EcDsbA-EcDsbB. Innovation: This study has characterized BpsDsbA biochemically and structurally and determined that it is required for virulence of B. pseudomallei. Conclusion: These data establish a critical role for BpsDsbA in B. pseudomallei infection, which in combination with our structural characterization of BpsDsbA will facilitate the future development of rationally designed inhibitors against this drug-resistant organism. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 20, 606–617.

Introduction

Burkholderia pseudomallei is a Gram-negative, soil-borne bacterium and the causative agent of melioidosis, a disease endemic in northern Australia and southeast Asia. Even with therapeutic intervention, the mortality rate of melioidosis is high; 14% (540 cases 77 deaths) in northern Australia between 1989 and 2009 (18), and 43% (2243 cases 956 deaths) in northeast Thailand between 1997 and 2006 (47). Melioidosis often affects individuals with compromised immune responses, and risk factors for infection include diabetes mellitus, high alcohol consumption, and chronic renal failure (13), and certain occupations that increase the likelihood of exposure (60). The route of exposure can be via inhalation or via cutaneous inoculation (13). B. pseudomallei is highly resistant to antibiotics, leading to concerns about its potential misuse as a biological weapon (9).

Melioidosis in humans presents as an acute septicemia or as a localized chronic infection and usually involves the formation of abscesses (68). Early clinical intervention is paramount due to the high mortality associated with delayed treatment (46). Treatment is prolonged, [10–14 days for the intravenous phase and then 3–6 months for oral treatment (13)] to facilitate clearance of infection and prevent relapse, and it can be complicated or ineffective due to the organism's potential to survive within the host in a latent form (10,52) and inherent resistance to a wide range of antibiotics. As a result, innovative therapeutic strategies and novel antimicrobial agents to counter infection are highly sought.

Innovation.

Burkholderia pseudomallei causes melioidosis, a disease for which current treatment options are limited. An important step in the early stages of drug discovery is to assess whether modulation of a target will provide therapeutic benefit during disease, preferably using an appropriate animal model. The role of DsbA from a Burkholderia species has not previously been determined in vivo. Therefore, the biochemical and structural characterization of DsbA from B. pseudomallei and validation of its key role in virulence is a crucial foundation for the next stage of therapeutic development.

Promising new antibiotic targets are members of the disulfide bond (DSB) family of thiol-disulfide oxidoreductases, which catalyze the introduction of disulfide bonds in unfolded or partially unfolded protein substrates. DSB proteins play a role in bacterial pathogenicity [reviewed by Heras et al. (30)] and are essential for the proper folding and activity of a range of virulence factors in a number of bacterial species including clinically significant pathogens such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, enteropathogenic Escherichia coli, and Neisseria meningitidis (30). In particular, disruption of disulfide bond protein A (DsbA), the primary oxidase in the family, has been variously demonstrated to modify bacterial adhesion (42), toxin and exoprotein formation (59,63), motility (32), and type III-mediated secretion (67). Bioinformatics analyses indicate that although diversity exists in disulfide bond formation pathways, most Proteobacteria encode members of the DsbA or DsbB machineries (20). Therefore, positioned at a branch point in the protein folding pathway of many bacteria, DsbA presents an opportunity to disrupt multiple downstream virulence effectors via its inhibition. Interrogation of the sequenced genome (34) of B. pseudomallei identified a DsbA homologue, prompting us to investigate its potential as an essential mediator of virulence in this pathogen.

In the present study, we demonstrate that DsbA from B. pseudomallei (BpsDsbA) is a highly oxidizing disulfide oxidoreductase similar in structure and activity to DsbA from P. aeruginosa (PaDsbA). A B. pseudomallei dsbA deletion mutant is attenuated in a murine model of infection, likely resulting from ΔdsbA generated pleiotropic effects on virulence factor production. Elucidation of a 1.9 Å resolution crystal structure provides a high-resolution snapshot of BpsDsbA's active site and putative DsbB engagement region, and is the primary tool for structure-based drug design programs to develop inhibitors of this virulence effector control protein.

Results

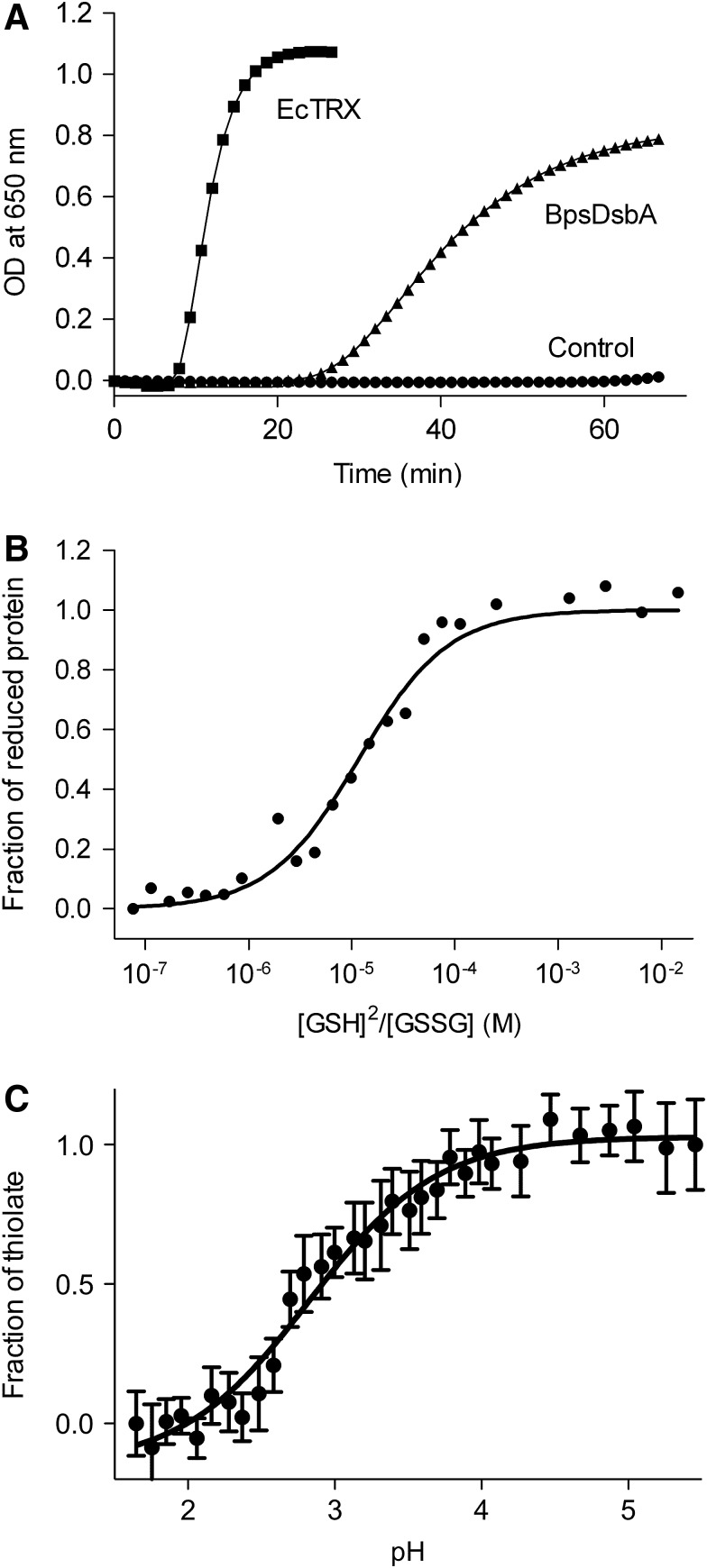

BpsDsbA catalyzes the reduction of insulin indicating it has redox activity

Purified recombinant BpsDsbA was assessed for its ability to catalyze insulin reduction in the presence of dithiothreitol (DTT). In this classic redox-activity assay when the intermolecular disulfide bond of insulin is reduced, chain B precipitates. Both BpsDsbA and E. coli thioredoxin (EcTRX) were able to catalyze the reduction of insulin by DTT as quantified by the onset of aggregation (defined as the time required for precipitated insulin to produce an A650 reading of 0.025). Recombinant EcTRX [9.78 min±0.29 standard error of the mean (SEM)] and BpsDsbA (25.56 min±1.11 SEM) significantly decreased the time of aggregation onset (p<0.001, Student's t-test) compared with the reduction of insulin by DTT alone (70 min±0.67) (Fig. 1A). Notably, BpsDsbA was much less active in this assay than the highly reducing thioredoxin suggesting that BpsDsbA is likely to be more oxidizing in character.

FIG. 1.

Characterization of BpsDsbA. (A) Reduction of insulin by DTT (●) in the presence of the catalysts thioredoxin (■) and recombinant BpsDsbA (▲). The enzyme reaction was performed on three separate occasions, mean and SEM were calculated (n=3). (B) Redox potential. The fraction of oxidized and reduced BpsDsbA after equilibrium in redox buffers containing varying ratios of glutathione reduced; glutathione oxidized, at pH 7.0, 310 K, was determined from the redox state-dependent fluorescence of BpsDsbA. These data were used to calculate Keq and subsequently the redox potential. Representative data of a single experiment of three performed are shown, plotted on a semi-log graph using a base 10 logarithmic scale for the X-axis and a linear scale for the Y-axis. For final redox potential determination, mean and SEM were calculated (n=3). (C) pKa determination of the active site cysteine of BpsDbA. pH dependence of the thiolate-specific absorbance signal [(A240/A280)reduced/(A240/A280)oxidized] was normalized and fitted according to the Henderson–Hasselbach equation. Data from three independent experiments are plotted, showing mean and SEM. DTT, dithiothreitol; SEM, standard error of the mean.

BpsDsbA is highly oxidizing

The redox potential of BpsDsbA was determined at pH 7.0 and 303 K from the equilibrium with glutathione. This gave an equilibrium constant (Keq) for BpsDsbA of 1.24±0.05×10−5 M, which equates to an intrinsic redox potential (Eo’) of −92 mV (Fig. 1B). Thus, BpsDsbA is as oxidizing as PaDsbA (Eo’=−94 mV) (57), more oxidizing than EcDsbA (Eo’=−122 mV) (38), and falls within the range of redox potentials for oxidizing DsbAs observed to date (Eo’=−80 to −163 mV).

BpsDsbA's active site nucleophilic cysteine has a particularly low pKa

The thiol groups of DsbA active site cysteines display distinct biochemical properties. In reduced EcDsbA, for example, the thiol group of the surface exposed Cys 30 is highly reactive and fully ionized even at acidic pH values, while the thiol group of Cys 33 is buried, unreactive, and ionizes much less readily (51). This is also the case for other DsbA homologues (31,45). Accordingly, the surface exposed reactive cysteine of a disulfide oxidoreductase usually has a much lower pKa value than is typical for a cysteine residue (∼8.5), a factor that directly influences enzyme reactivity. The pH-dependent ultraviolet (UV) absorbance of the surface exposed Cys 43 thiolate anion in BpsDsbA was measured and fitted to the Henderson–Hasselbalch equation. The pKa of BpsDsbA was determined as 2.83±0.04 (Fig. 1C), which is 0.5 pH units lower than that of EcDsbA (3.3) and to our knowledge, the lowest pKa of a DsbA nucleophilic cysteine reported to date. This low pKa is consistent with the highly oxidizing redox potential of BpsDsbA.

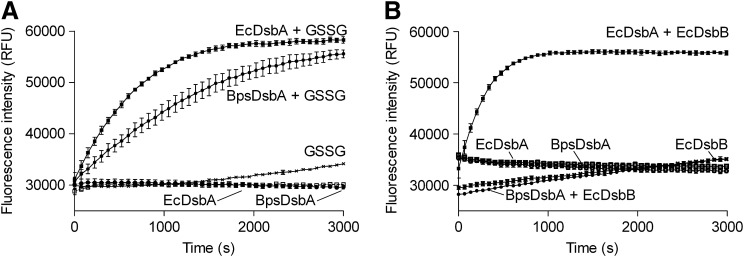

BpsDsbA has disulfide oxidase activity in vitro and in vivo

E. coli deficient in EcDsbA do not form fully functional flagella filaments (19) and are, as a consequence, nonmotile. Exogenous expression of BpsDsbA is sufficient to complement EcDsbA deficiency in E. coli restoring flagella filament formation and motility on soft agar. Expression of EcDsbA or BpsDsbA could not, however, restore motility in EcDsbA/EcDsbB double null E. coli consistent with a requirement for EcDsbB to replenish the pool of oxidized DsbA in each case. Notably, the diameter of the zone of motility arising from BpsDsbA complementation is approximately half that of those resulting from EcDsbA expression (Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/ars). BpsDsbA oxidase activity was further assessed in vitro by monitoring its ability to catalyze oxidation of a peptide substrate. Both BpsDsbA and EcDsbA protein, in the presence of 2 mM oxidized glutathione (required to maintain oxidized DsbA), efficiently catalyze oxidation of the peptide substrate relative to oxidized glutathione alone (Fig. 2A). In the absence of oxidized glutathione, BpsDsbA and EcDsbA exhibit no oxidative activity. We note that while BpsDsbA is active in this assay in the presence of glutathione redox buffer, it shows only weak activity in the presence of EcDsbB, in contrast to EcDsbA, which in the same assay is active in the presence of either glutathione or its redox partner EcDsbB (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

BpsDsbA oxidizes a fluorescently labeled peptide substrate. (A) 160 nM BpsDsbA (●) and 160 nM EcDsbA (■) protein (positive control) in the presence of 2 mM oxidized glutathione, efficiently catalyze the oxidation of a peptide substrate relative to oxidized glutathione alone (x), as indicated by monitoring an oxidation dependent fluorescence signal (excitation λ 340 nm, emission λ 615 nm). In the absence of glutathione, BpsDsbA (○) and EcDsbA (□) exhibit no oxidative catalytic activity. Mean and SEM are shown (n=3). (B) In the presence of 1.6 μM EcDsbB (crude membrane preparation) 160 nM EcDsbA (■) protein (positive control), but not 160 nM BpsDsbA (●) efficiently oxidizes a peptide substrate relative to EcDsbB alone (x). In the absence of EcDsbB, EcDsbA (□) and BpsDsbA (○) exhibit no oxidative catalytic activity. Mean and SEM are shown (n=3).

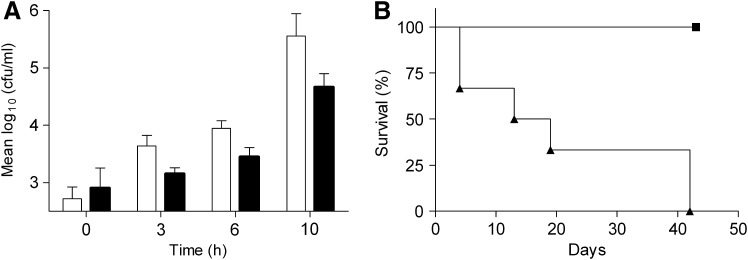

ΔdsbA has reduced virulence in macrophages and a murine model of melioidosis

BpsDsbA has 88% and 44% sequence identity to Burkholderia cepacia DsbA and PaDsbA, respectively. Previous studies with B. cepacia (29) and P. aeruginosa (28) revealed DsbA was required for the production of multiple virulence factors, leading us to hypothesize a similar role for DsbA in B. pseudomallei. To address this question, and to investigate BpsDsbA as a potential antibiotic target, we constructed an in-frame allelic B. pseudomallei deletion mutant to generate ΔdsbA. The mutation was confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), sequencing and Southern hybridization (Supplementary Fig. S2).

There was no difference in growth between wild-type (WT) and ΔdsbA cultured in Luria broth (LB) (p>0.05) at 310 K (data not shown). We therefore examined the effect of disrupting the dsbA gene on intracellular survival and growth of B. pseudomallei in vitro by infecting J774.A1 macrophages (Fig. 3A). There was no difference in the ability of ΔdsbA to initially infect macrophages compared to WT (p>0.05). However, ΔdsbA had reduced intracellular numbers over the infection period of 10 h (p<0.05 two-way analysis of variance [ANOVA], repeated measures) relative to WT.

FIG. 3.

Deletion of dsbA attenuates virulence in vitro and in vivo. (A) Intracellular survival of Burkholderia pseudomallei WT (white bars) and ΔdsbA (black bars) in J774A.1 macrophages. Mean values are plotted from three experiments with SEM. (B) ΔdsbA is significantly attenuated compared with WT in a murine model of infection [log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test p<0.001]. Groups of six BALB/c mice were infected by the intraperitoneal (i.p.) route with B. pseudomallei strains: WT 3.43×104 CFU (▲), ΔdsbA 5.77×104 CFU (■).WT, wild type; CFU, colony forming unit.

Groups of six BALB/c mice were challenged via the intra-peritoneal route with WT B. pseudomallei or ΔdsbA (Fig. 3B). There were no deaths in the group infected with ΔdsbA compared with the group infected with WT in which all members had succumbed to disease by 42 days post challenge. The bacterial burden in the survivors was examined by removing organs and enumerating colony forming units (CFUs). Mice infected with ΔdsbA failed to clear the infection; bacterial colonization remained in the liver, lungs, and spleens with medians of 3.5×102, 1.3×104, and 3.3×101 CFU/ml, respectively.

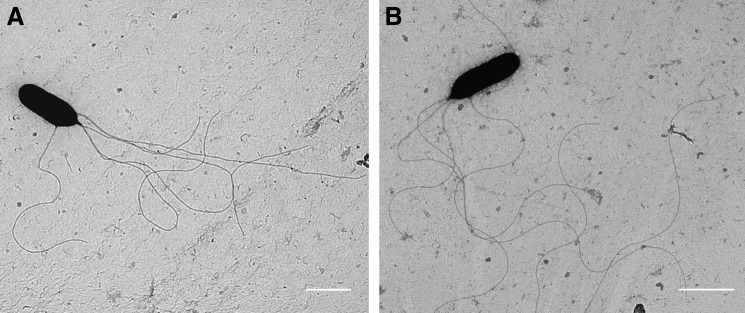

B. pseudomallei ΔdsbA has pleiotropic phenotypes

Phenotypic studies were performed to examine the effect of dsbA deletion. ΔdsbA when stab inoculated into 0.3% agar was less motile than WT (n=6, p<0.001 unpaired Student's t-test). The mean zone of motility for the WT strain was 57 mm (±0.6 SEM) compared with 13 mm (±0.2 SEM) produced by the deletion mutant. However, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) revealed the presence of flagella on both WT and the mutant strain (Fig. 4). We evaluated the enzyme activity of culture supernatant from ΔdsbA. Following 6.5 h incubation with azocasein, culture supernatant from ΔdsbA had reduced protease activity when compared with WT B. pseudomallei. In addition, phospholipase C (PLC) activity of culture supernatants from WT and ΔdsbA were compared using a p-nitrophenylphosphorylcholine (pNPPC) assay. At 5 h, supernatant derived from WT culture had hydrolyzed pNPPC to a greater extent than ΔdsbA as indicated by absorbance change (Table 1); this difference represented a mean fold change of 1.34.

FIG. 4.

Transmission electron microscopy reveals B. pseudomallei ΔdsbA retains flagella. (A) B. pseudomallei WT and (B) ΔdsbA were prepared following 18 h culture at 37°C by washing, fixation with formalin, and negative staining with 2% wt/vol uranyl acetate. Scale bars represent 1 μm.

Table 1.

Reduced Secretion of Protease and Phospholipase C in a Burkholderia Pseudomallei DsbA Mutant Strain

| A440a | A415b | |

|---|---|---|

| Supernatant | Azocasein hydrolysis | pNPPC hydrolysis |

| WT | 0.293±0.023 | 0.420±0.027 |

| ΔdsbA | 0.017±0.009***,c | 0.314±0.020* |

| Controld | 0.393±0.009 | 0.384±0.027 |

The values are mean±standard error from triplicate A440 values obtained after incubation of B. pseudomallei culture supernatants with the protease substrate azocasein at 5 mg/ml. Release of the azo dye following hydrolysis of casein by secreted bacterial proteases was measured after 6.5 h incubation at 37°C.

Data represent mean±standard error from five replicate A415 values following incubation of concentrated culture supernatant with pNPPC for 5 h at 37°C.

Asterisk represent statistical difference of enzyme activity of culture supernatant prepared from WT or B. pseudomallei ΔdsbA using an unpaired Student's t-test with *p<0.05 and ***p<0.001.

Trypsin (28.6 units) was used for positive control for Azocasein hydrolysis and phospholipase C (5 units) from Bacillus cereus (Sigma) used for pNPPC hydrolysis.

pNPPC, p-nitrophenylphosphorylcholine; WT, wild type.

1.9 Å resolution crystal structure of BpsDsbA

The crystal structure of BpsDsbA was determined to 1.9 Å resolution, with an Rfactor of 15.4% (Rfree of 19.2%) indicating that the refined model represents the diffraction data with high accuracy. The structure contains residues 7–197 inclusive of BpsDsbA. Additionally, the structure contains 145 water and 3 glycerol molecules (presumed to be acquired from the cryoprotectant solution). The quality of the electron density maps and Molprobity values indicate that the final structure is of high quality. Details of data collection, solution methods, and additional indicators of the quality of the final model are given in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

X-Ray Data Collection Statistics

| SeMet BpsDsbA L83M L132M | Wild-type BpsDsbA | |

|---|---|---|

| Data collection | ||

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.97930 | 0.95370 |

| Resolution (Å) | 68.3–2.50 | 46.2–1.9 |

| Spacegroup | P212121 | P212121 |

| Unit cell dimensions (Å,°) | a=59.69, b=61.44 | a=59.32, b=62.30 |

| c=68.33 | c=68.78 | |

| α=β=γ=90.0 | α=β=γ=90.0 | |

| Observed reflections | 250265 | 140971 |

| Unique reflections | 9208 | 20726 |

| Rmerge | 0.142 (0.725) | 0.102 (0.732) |

| Rmeas | 0.147 (0.751) | 0.111 (0.79) |

| Rpim | 0.030 (0.143) | 0.043 (0.296) |

| Completeness (%) | 100 (100) | 100 (100) |

| I/σI | 23.6 (5.9) | 10.1 (2.6) |

| Multiplicity | 27.2 (27.6) | 6.8 (7.0) |

| SAD phasing | ||

| Resolution (Å) | 68.3–2.50 | – |

| Number of selenium atoms found/expected | 3/3 | – |

| Mean figure of merit | 0.36 | – |

Values in parentheses refer to the highest resolution shell.

SAD, single-wavelength anomalous dispersion.

Table 3.

Refinement Statistics for Wild-Type BpsDsbA

| Refinement | |

| Resolution (Å) | 44.9–1.9 |

| Completeness for range (%) | 99.97 |

| Rfactora | 15.86 (22.07) |

| Rfreeb | 19.28 (26.90) |

| Number of non-H protein atoms | 1500 |

| Number of waters | 145 |

| Number of non-H GOL atoms | 3×6 |

| B factors (Å2) | |

| Wilson | 29.50 |

| All atom/water | 35.90/39.40 |

| r.m.s.d. from ideal geometry | |

| Bonds (Å) | 0.012 |

| Angles (°) | 1.3 |

| Molprobity analysis | |

| Ramachandran favored/allowed/outliers (%) | 97.88/2.12/0 |

| Residues with bad bonds/angles (%) | 0/0 |

| Poor rotamers (%) | 0.62 |

| Clashscore (percentile) | 2.28 (99th) |

| Molprobity score (percentile) | 1.03 (100th) |

Values in parentheses refer to the highest resolution shell.

, where h Hdefines the unique reflections.

, where h Hdefines the unique reflections.

Rfree calculated over 5.0% of total reflections excluded from refinement.

r.m.s.d., root mean squared deviation.

The structure of BpsDsbA exhibits the hallmarks of a classic DsbA protein, namely, a thioredoxin core with an inserted α-helical domain and a di-cysteine active site motif (Cys-Pro-His-Cys) (Fig. 5A) that it shares with EcDsbA. The closest known structural homologue of BpsDsbA is PaDsbA [Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID 3H93]; the structures superimpose with a root mean squared deviation (r.m.s.d.) of 1.6 Å (calculated between 191 Cα atoms) (Fig. 5A). Despite the gross similarity, there are minor structural deviations between the two proteins, the most marked of which is at the N-terminal end of α3 helix, which contains an additional helical turn in BpsDsbA relative to PaDsbA, where the equivalent residues adopt a less constrained coil formation. This is likely the result of an electrostatic interaction in PaDsbA between the side chains of residues Glu 82 (α2 helix) and His 91 (α3 helix) (absent in BpsDsbA where the equivalent residues are Ala and Thr), which constrains the α2-α3 turn, precluding the formation of an additional helical turn in α3.

FIG. 5.

The crystal structure of BpsDsbA is similar to PaDsbA but exhibits distinct differences from EcDsbA that may impact upon DsbB engagement. (A) Superposition of the crystal structure of BpsDsbA upon its closest structural homologue PaDsbA, and EcDsbA. BpsDsbA is colored light green, PaDsbA is colored dark green, and EcDsbA is colored magenta. The sulfur atoms of Cys 43 and Cys 46 of the active site in BpsDsbA are shown as spheres and colored yellow. The β5-α7 loop that is significantly shortened in BpsDsbA and PaDsbA, relative to EcDsbA, and the loop that is differently positioned between BpsDsbA and PaDsbA, and EcDsbA are each highlighted with a dashed ellipse. Enlarged views of the β5-α7 and β3-α2 loops are shown in the adjacent panels. (B) Surface representation of BpsDsbA (upper left panel) and EcDsbA (upper right panel), illustrating the nature of the DsbB-engaging groove (indicated with a dashed ellipse) positioned immediately beneath the active site (indicated with an S). The view has been rotated 45° anticlockwise about the Y-axis relative to A. Surface residues are colored on a gradient from white to dark green according to the Eisenberg hydrophobicity scale; white indicates most hydrophobic, dark green indicates least hydrophobic. In BpsDsbA the β5-α7 loop is three residues shorter than in EcDsbA. This directly impacts upon the depth and extent of the putative DsbB-engaging groove. Figures were generated using Pymol (www.pymol.org/).

While structurally highly similar to PaDsbA, BpsDsbA exhibits marked structural deviations from the canonical EcDsbA (PDB ID 1DSB); namely, conformational and positional differences at the N-terminus of helices α2 and α4, and in the β1-β2 and β5-α7 connecting loops (Fig. 5A). Indeed, across a number of DsbAs from Gram-negative bacteria, distinct structural features in these regions (31,37,58,66) appear to demarcate discrete DsbA subclasses. Of these variations the most striking difference is in the β5-α7 loop region, previously noted to be distinct between PaDsbA and EcDsbA and to vary among DsbA structures more generally (58). A three amino acid truncation in BpsDsbA relative to EcDsbA shortens this loop, directly influencing the extent of the surface groove positioned below the active site (Fig. 5B). The extent of this groove, the primary site at which DsbB engages with DsbA and a common feature of many DsbA structures, is reduced in PaDsbA relative to the model protein EcDsbA and is even shallower and less clearly demarcated again in BpsDsbA (Fig. 5B). In EcDsbA, this groove is predominantly hydrophobic in character (Fig. 5B) (49). The side chains of the residues that line the equivalent “groove” in BpsDsbA are similarly hydrophobic in character (Phe 55, Ile 53, Leu 178, Thr 181, Leu 185, and Val 189) although the relative hydrophobic surface area available for the predicted engagement with DsbB is reduced. Also of note is the repositioning of the loop connecting β3 strand and α2-helix between BpsDsbA and PaDsbA, and EcDsbA (Fig. 5A). In EcDsbA, this loop has been identified as a secondary DsbB interaction site, binding PL2’ of the DsbB periplasmic loop 2 (PL2) (40,73).

The active site dipeptide motif (CXXC) and the residue immediately N-terminal to a conservative cis-Proline influence the redox character of thioredoxin-fold proteins (38,55). The cisPro-1 residue is either Val or Thr, and when it differs between proteins with a common CXXC motif, correlates with less or more oxidizing redox character respectively as a result of additional stabilization of the nucleophilic thiolate anion by hydrogen bonding interactions with the polar side chain of Thr relative to Val. A structural reason for the more oxidizing character of BpsDsbA relative to EcDsbA is not apparent. The active site of BpsDsbA and EcDsbA are almost identical: BpsDsbA and EcDsbA share a CPHC motif and a Val at the cisPro-1 position (Supplementary Fig. S3). Differences in the redox activity (redox potential and pKa) between these two proteins must result from additional subtle structural contributions to relative thiolate stability.

Discussion

B. pseudomallei causes a debilitating disease in humans and is resistant to many antibiotics including cephalosporins, aminoglycosides, penicillins, polymyxins, and macrolides (69,72). Coupled with the global antibiotic resistance problem (6), there is a pressing need to identify new targets in Gram-negative bacteria and develop antimicrobials against them and to adopt therapeutic strategies likely to limit the subsequent evolution of multidrug resistance against them. Members of the DSB oxidoreductase protein family have been earmarked as prospective targets fulfilling both of these criteria (30,37,57,66). DSB inhibition is anticipated to ameliorate bacterial virulence by interrupting the correct folding and function of multiple DSB-dependent virulence factors (30). Moreover, targeting virulence rather than bacterial growth has been suggested as a potential approach to avoid the strong selection pressure to acquire resistance that is associated with inhibition of bacterial replication (8,54). Data presented here confirm that DsbA is an essential mediator of virulence in B. pseudomallei and that its disruption has pleiotropic effects, thereby validating it as a promising drug target in this organism.

B. pseudomallei ΔdsbA were nonmotile, and attenuated in macrophages and a BALB/c mouse model of infection. Loss of motility in E. coli following dsbA mutation has been attributed to an absence of disulfide bonds in the P-ring structural protein of the flagella basal body (19,33) rather than a loss of flagella per se. This also appears to be the case in B. pseudomallei (this study) and B. cepacia (29) where flagella filaments can be observed on the cell surface of non-motile mutant strains using TEM. Flagella have been associated with the virulence of B. pseudomallei previously; a strain defective in the flagella structural subunit (fliC) showed attenuation in the BALB/c mouse model of infection (16) and reduced uptake in both non-phagocytic macrophages (17) and amoeba (41). In addition, antibodies against purified flagellin were capable of protecting diabetic rats from B. pseudomallei challenge (7).

Secreted proteins and exoproteins associated with virulence often employ disulfide bonds to maintain stability in the harsh extracellular environment encountered during infection (57). This study shows that culture supernatants, prepared from late exponential phase ΔdsbA cells, had reduced protease activity. B. pseudomallei is known to secrete the serine metalloprotease MrpA but the role of protease in B. pseudomallei infection is not yet clear (14). Protease purified from B. pseudomallei culture supernatant is known to degrade host proteins and immunization with purified MrpA shown to induce a protective immune response in mice (15,56). In addition, a protease-deficient strain of B. pseudomallei was attenuated in an animal lung model of infection (56). However, a separate study found that it was not required for virulence in a SWISS mouse model (26,64). Secretion of PLC was also reduced in culture supernatant. B. pseudomallei encodes three PLC genes of which two have been characterized and shown to play a role in eukaryotic cell infection (43). Previously, single or double deletion mutations in PLC genes have indicated a level of redundancy (43) that may account for the minor reduction in PLC secretion observed in the present study. Taken together it is clear that disruption of dsbA in B. pseudomallei has pleiotropic effects, ablating bacterial motility and compromising secreted virulence protein activity, resulting in full attenuation in a mouse model of infection.

Most modern drug development programs exploit structure-based drug design strategies. BpsDsbA expresses with high yield, crystallizes readily, and diffracts to high resolution (Tables 2 and 3; Fig. 5) making it an excellent candidate for drug development using this methodology. Inhibition of BpsDsbA, and that of DsbAs more generally, could be targeted by direct interruption of catalytic activity at the active site or more likely, prevention of a productive interaction of DsbA with DsbB. Targeting protein–protein interactions of this nature is challenging, as these typically flat protein surfaces lack the characteristic deep cavities and active site pockets of the so-called “druggable genome” (36). Despite this, there have been recent successes in structure-based drug design programs against such targets (1) supporting the pursuit of DSB inhibitor development. Further, several recent structures of DsbA proteins reiterate the potential for small molecule binding to this family of proteins (45,57,66). While there is no functional inhibition realized by these fortuitous ligand–DsbA interactions, they indicate that cavities on the surface of DsbA, in the vicinity of the active site, can accommodate small molecules. This indicates that DsbA may be compatible with a fragment-based drug design program in which the screening of a library of low-molecular-weight compounds is performed to identify scaffolds for subsequent elaboration and the formation of high affinity drug-like molecules (24).

Discrete structural features of BpsDsbA, in comparison with EcDsbA, raise questions about the development of class specific DsbA inhibitors. Conformational distinctions in the landscape of the hydrophobic groove (the site of DsbB engagement) suggest that drugs that are effective against the former may not be effective against the latter and vice versa (Fig. 5B). To date, despite evidence of significant diversity in bacterial DSB machinery (20), most studies have focused on the model organism E. coli strain K12 and this is the only system for which high resolution information detailing the molecular nature of DsbA-DsbB engagement is available (39,40,73). In the E. coli system, a segment (Pro 100–Phe 106) of PL2 of DsbB is accommodated in the α5-β7 demarcated groove on EcDsbA to form the EcDsbA-EcDsbB complex. In particular, the bulky side chains of Pro 100EcDsbB and Phe 101EcDsbB insert into the groove immediately beneath the active site residue His 32EcDsbA, forming a stable anchor to position the reactive Cys 103DsbB and facilitate DsbA reoxidation. The equivalent predicted BpsDsbA interacting region of BpsDsbB is shorter by two residues and lacks a residue equivalent to Pro 100EcDsbB (Supplementary Fig. S4). Simple superposition of BpsDsbA upon EcDsbA in the EcDsbA-EcDsbB crystal structure results in extensive clashes between the PL2 loop of EcDsbB and BpsDsbA (Supplementary Fig. S4A, B). It is thus unclear how DsbAs that have a greatly truncated or shallower groove, such as PaDsbA or BpsDsbA, engage their partner DsbB.

We propose that the model of DsbA:DsbB engagement described for E. coli is unlikely to account for all bacterial organisms, particularly those sharing features of BpsDsbA. This is supported by the observation that while BpsDsbA is able to complement an EcDsbA deficient E. coli strain to restore flagellar mediated motility, the resulting zones of motility are reduced in diameter relative to that of EcDsbA controls (Supplementary Fig. S1). Further, recombinant BpsDsbA could not be reoxidized by EcDsbB on the timescale of a peptide oxidation assay (Fig. 2B). Together these point to an inefficient BpsDsbA–EcDsbB interaction, potentially a consequence of the shortened groove in BpsDsbA. Therefore, in order to develop inhibitors to interrupt the DsbA:DsbB complex in a variety of bacterial species, additional high resolution structural knowledge of this interaction in systems other than the model E. coli would be highly beneficial. The development of class-specific inhibitors nods to an exciting era of personalized medicine, but would necessitate rapid diagnoses and identification of the responsible organism, and thus significant changes in clinical practice.

Organs removed from ΔdsbA-infected mice on the final study day, revealed bacterial burden, demonstrating the mutant strain was able to colonize mice although without causing visible disease symptoms. Development of anti-virulence therapies is in its infancy and much remains to be determined about the practical requirements of therapeutic delivery. Anti-virulence measures alone may contain an infection sufficient to enable the host's immune system to clear it, but in the case of BpsDsbA inhibition, combination therapy with traditional antibiotics is likely to be necessary for complete pathogen clearance.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that DsbA is required for virulence of B. pseudomallei. The pleiotropic phenotypes observed indicate that this protein plays a central role in mediating multiple virulence pathways and therefore represents an attractive target for therapeutic intervention. The structural and functional characterization of BpsDsbA reported here can now form the basis for drug discovery studies against this highly resistant organism.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

Strains of B. pseudomallei and E. coli were routinely cultured using LB. Where required, media were supplemented with 50 μg/ml chloramphenicol and 100 μg/ml ampicillin. Chemicals and reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich unless specified. All work undertaken with Burkholderia strains was performed under appropriate laboratory containment conditions in accordance with relevant legislative requirements.

Cloning, expression, and purification of BpsDsbA

The B. pseudomallei dsbA gene lacking the signal sequence was synthesized and codon optimized by GeneArt (Life Technologies) and inserted into either a modified pET22 plasmid using ligation-independent cloning methods as described previously (57), or pET21b. The resulting constructs had a Tobacco Etch Virus protease cleavable N-terminal His6-tag, or a non-cleavable C-terminal His6-tag, respectively.

For crystallization experiments and all biochemical characterizations (except the insulin reduction assay) the N-terminal His6-tagged BpsDsbA construct was expressed and purified as previously described for PaDsbA (57). For the insulin reduction assay, the C-terminal His6-tag construct was expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) at 310 K under isopropyl β-D-thiogalactopyranoside induction and purified using immobilized metal affinity chromatography. Additional details of cloning, expression, and purification methods are provided in Supplementary Data.

Insulin reduction assay

The insulin reduction assay was carried out as previously described (35). Briefly, reaction mixtures were prepared containing 8 μM recombinant BpsDsbA or recombinant thioredoxin from E. coli 0.1 M phosphate buffer, 2 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), and 0.35 mM DTT. The reactions were started by adding insulin to a final concentration of 131 μM and the reduction of insulin was monitored at A650 for 80 min at 20 s intervals using a Shimadzu 1800 UV/visible spectrophotometer. The non-catalyzed reduction of insulin by DTT was monitored in a control reaction without catalyst.

Redox potential determination

The redox potential of BpsDsbA was determined fluorometrically, by exploiting redox-state dependent changes in the intrinsic fluorescence of a tryptophan residue close to the catalytic disulfide bridge. Oxidized and reduced BpsDsbA were prepared by incubation with a molar excess of oxidized glutathione and reduced glutathione, respectively. Oxidizing and reducing agents were subsequently removed by gel filtration using a NAP-5 desalting column (GE Healthcare). The redox state of the protein was confirmed by Ellman assay (22). Oxidized BpsDsbA (2 μM) in 100 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.0, 0.1 mM EDTA, was combined with oxidized glutathione (1 mM) and a range of concentrations of reduced glutathione (4 μM–100 mM) and incubated at 303 K overnight. The fraction of reduced and oxidized BpsDsbA at equilibrium was determined from the relative fluorescence intensity of each reaction (excitation 280 m, emission 322 nm), recorded in a black 96-well OptiPlate (Perkin Elmer) on a Synergy H1 multimode plate reader (Biotek). Three independent experiments were performed to determine the equilibrium constant with glutathione. The redox potential was calculated using the Nernst equation as described previously (71).

pKa determination

The pKa of the nucleophilic cysteine (Cys 43) thiol was determined by measuring the pH-dependent UV absorbance of the thiolate ion at 240 nm as described previously (51). Measurements were taken of reduced and oxidized protein (20 μM) (prepared as described above), in 10 mM dipotassium phosphate (K2HPO4), 10 mM boric acid, 10 mM sodium succinate, 1 mM EDTA, and 200 mM potassium chloride over a pH range of 1.6–5.4, in a total volume of 200 μl, using 96-well UV-Star® microplates (Greiner, Interpath Services). Measurements were performed in a Synergy H1 multimode plate reader. The pH-dependent specific absorbance of the thiolate anion was measured and corrected for buffer absorbance, non-specific absorption at 240 nm (absorption of the oxidized protein) and corrected for minor variations in protein concentration (absorption at 280 nm) in the following manner [(A240/A280)reduced/(A240/A280)oxidized)] and fitted to the Henderson–Hasselbalch equation.

Peptide oxidation assay

The oxidase activity of BpsDsbA was assayed using a cysteine pair containing reporter peptide substrate, of which its ability to fluoresce is directly coupled to its oxidation state (66). The substrate is dually labeled with a chromophore [methylcoumarin amide (MCA)] and lanthanide metal ion (europium) which, in the reduced state are spatially distant from one another, but in the oxidized state are in sufficiently close proximity to support efficient energy transfer. Oxidation of the peptide substrate can be followed by measuring the fluorescence emission intensity of europium after specific MCA excitation. Accordingly, 160 nM BpsDsbA in 50 mM 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (pH 5.5), 50 mM sodium chloride, and 2 mM EDTA was combined with 2 mM oxidized glutathione or 1.6 μM EcDsbB (added as a crude membrane preparation) and 8 μM peptide substrate in a total volume of 50 μl. Oxidation of the peptide substrate was monitored in a Synergy H1 multimode plate reader, using 384-well white OptiPlates (Perkin Elmer), with excitation at 340 nm and emission at 615 nm, a 150 ms delay before reading and a 100 ms reading time. EcDsbA was included as a reference.

Motility assays

BpsDsbA was inserted into the expression vector pBAD33 (27) under the control of an arabinose inducible promoter and 3′ of an E. coli specific signal peptide sequence. Two E. coli strains, JCB817 and JCB818 (4), deficient in E. coli DsbA or E. coli DsbA and DsbB, respectively, were transformed with pBAD33-BpsDsbA or pBAD33-EcDsbA and grown on LB agar. Liquid cultures (10 ml) were grown (310 K, 200 rpm) in M63 minimal media lacking cysteine or methionine. One microliter of each culture (normalized to an OD600 of 1.0), was used to stab inoculate M63 minimal media soft agar in the presence or absence of arabinose (1 mg/ml). Plates were incubated at 310 K for ∼8 h.

Additionally, to assess the motility of ΔdsbA relative to WT, colonies of the mutant and WT strains were stabbed into the center of motility agar (L-agar 0.3%) and incubated at 310 K. The zone of motility was measured after 20 h.

Generation of a B. pseudomallei ΔdsbA mutant strain

A 1074 bp sequence consisting of DNA flanking the BPSL0381 (dsbA) gene from the B. pseudomallei K96243 genome was synthesized by GeneArt. The synthesized sequence was ligated into the suicide vector pDM4 to produce pDM4ΔdsbA. The generation of an in-frame deletion mutant was carried out as previously described (48). Briefly, pDM4ΔdsbA was mobilized into B. pseudomallei K96243 by conjugation. Chloramphenicol and ampicilin was used to select merodiploid B. pseudomallei colonies. Following confirmation by PCR, the colonies were cultured overnight in LB and then subjected to sucrose selection. Chloramphenicol sensitive colonies were screened for deletion of dsbA using the primers dsbAScrF (TCGAACAACAACGGCAACGG) and dsbAScrR (ATCGTCACGACCGCGACTTG).

Virulence in BALB/c mice

Female BALB/c age-matched mice, ∼6 weeks old, were used in this study. The mice had access to food and water and were grouped together in cages of six with 12 h light/dark cycles. For challenge with viable B. pseudomallei, the animals were handled under biosafety level III containment conditions within a half-suit isolator, compliant with British Standard BS5726. All investigations involving animals were carried out according to the requirements of the Animal (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986. Humane endpoints were strictly observed and animals deemed incapable of survival were humanely killed by cervical dislocation. Groups of six BALB/c mice were challenged with 3.43×104 CFU of WT B. pseudomallei strain K96243 or 5.77×104 CFU ΔdsbA by the i.p. route and the animals were monitored for 6 weeks.

Survival in J774.A1 macrophages

The intracellular macrophage survival assay was performed as described previously with minor modifications (53). Briefly, J774A.1 murine macrophage cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 1% L-glutamine, in 24-well tissue culture plates at 310 K with 5% (v/v) CO2. B. pseudomallei strains were prepared from overnight broth cultures and adjusted in L-15 medium containing 10% fetal calf serum. Macrophages were infected at a multiplicity of infection of 10 for 30 min at 310 K. The bacteria were removed by washing once with pre-warmed phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and the remaining extracellular bacteria killed using L-15 containing 750 μg/ml of kanamycin. Following 1 h incubation the antibiotic was removed and replaced with L-15 media containing 250 μg/ml kanamycin. Intracellular bacterial counts were determined by removing the medium and replacing with 1 ml of distilled water to lyse the cells followed by serial dilution and plate counts.

Protease assay

The activity of secreted B. pseudomallei protease was assayed as previously described with minor modifications (11). B. pseudomallei strains were each inoculated into 50 ml of LB and incubated for 7 h at 310 K, shaking at 180 rpm. The supernatant fraction was collected by centrifugation at 6000 g for 10 min, then passed through a 0.2 μm filter to ensure no bacteria remained and concentrated using Amicon Ultra centrifugation filters with a 10 kDa molecular weight cutoff. Each replicate was prepared by concentrating 1 ml of supernatant to 40 μl. Azocasein (5 mg/ml) was prepared in 0.05 M Tris-HCL. Reactions were prepared with 35 μl supernatant with 100 μl azocasein incubated at 310 K. The reaction was stopped using 10% trichloacetic acid followed by centrifugation at 12,100 g for 15 min to remove the insoluble azocasein. The supernatant was adjusted to 500 mM sodium hydroxide and the absorbance measured at 440 nm.

PLC assay

Culture supernatant was prepared as described for the protease assay but without concentration of the supernatant. PLC activity was determined through the breakdown of pNPPC. The reaction was prepared as described previously but with minor modifications: a 20 mM solution of pNPPC was prepared in 0.25 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.0) containing 60% glycerol (v/v) and 1 mM zinc chloride (44,65). The reaction was initiated by the addition of 10 μl supernatant to 190 μl of reaction reagent and the A440 measured after 5 h incubation at 310 K.

Electron microscopy

WT B. pseudomallei and ΔdsbA were grown as shaking 50 ml LB cultures for 18 h at 310 K. Culture was removed (2 ml) from each and washed four times with PBS through microcentrifugation at 6000 rpm. Following the final wash bacteria were resuspended into 4% formalin and incubated at 310 K for 24 h. Cells were stained using 2% (wt/vol) uranyl acetate and viewed using FEI CM12 transmission electron microscope operating at 80 kV.

Selenomethionine labeling, crystallization, and data collection

To favor experimental phasing using a recombinant selenomethionine (SeMet) incorporation approach, a methionine enriched version of BpsDsbA (BpsDsbA L83M L132M) was constructed. SeMet BpsDsbA was produced using a protocol similar to that previously described (21) and purified as described for WT BpsDsbA. BpsDsbA was crystallized using the UQ ROCX Facility and the vapor-diffusion method. Single rod-shaped crystals were obtained in 0.29 M monosodium phosphate and 1.0 M K2HPO4 (hanging drop, 100 nl of protein at 43 mg/ml and 100 nl of reservoir solution). Crystals of SeMet labeled BpsDsbA L83M L132M grew in the same condition (using a protein concentration of 44 mg/ml). All crystals were harvested and cryocooled using 25% glycerol as a cryoprotectant. X-ray data were collected at 100 K at the Australian Synchrotron at the microfocus beamline MX2. The data were indexed and integrated with iMosflm (5), and scaled using POINTLESS and SCALA (25) within the CCP4 suite (70). Additional details of SeMet labeling, crystallization, and data collection are provided in Supplementary Data.

Data processing and structure solution

All phasing and model refinement procedures were implemented within the Phenix software suite (2). Single-wavelength anomalous dispersion phasing was performed using the automated search procedure AutoSol (61). Subsequent automated model building [AutoBuild, (62)] generated a model that was in turn used to phase data collected from WT BpsDsbA using molecular replacement methods with AutoMR (50). The resulting model was subjected to iterative rounds of refinement (phenix.refine (3) (including refinement using translation/liberation screw groups and of hydrogens using a riding model) and model building [COOT (23)]. Coordinates and restraints for glycerol molecules were generated using eLBOW (61) and the quality of the final model was assessed with Molprobity (12). Data collection and refinement statistics are summarized in Tables 2 and 3. The structure has been deposited in the PDB (ID 4K2D).

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations Used

- CFUs

colony forming units

- DSB

disulfide bond protein

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- IMAC

immobilized metal affinity chromatography

- K2HPO4

dipotassium phosphate

- LB

Luria broth

- MCA

methylcoumarin amide

- NaCl

sodium chloride

- NaH2PO4

monosodium phosphate

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PDB

Protein Data Bank

- PL2

periplasmic loop 2

- PLC

phospholipase C

- pNPPC

p-nitrophenylphosporylcholine

- r.m.s.d.

root mean squared deviation

- SAD

single-wavelength anomalous dispersion

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- SEM

standard error of the mean

- SeMet

selenomethionine

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy

- TEV

tobacco etch virus

- TRX

thioredoxin

- UV

ultraviolet

- WT

wild type

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Transformational Medical Technologies program contract W911NF-08-0023 from the Department of Defense Chemical and Biological Defense program through the Defense Threat Reduction Agency, and by the UK Ministry of Defense. We are grateful to Simon Smith for assistance with the electron microscopy. Jennifer Martin is supported by an Australian Research Council (ARC) Australian Laureate (FL0992138) Fellowship. Róisín McMahon is supported by an ARC Linkage grant (LP0990166). We acknowledge use of the Australian Synchrotron and the support of MX2 beamline scientists Alan Riboldi-Tunnicliffe and Tom Caradoc-Davies. We also thank Karl Byriel and Gordon King for their support and access to the UQ ROCX Diffraction Facility.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Abdel-Rahman N, Martinez-Arias A, and Blundell TL. Probing the druggability of protein-protein interactions: targeting the Notch1 receptor ankyrin domain using a fragment-based approach. Biochem Soc Trans 39: 1327–1333, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, and Zwart PH. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66: 213–221, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Afonine PVG-KRWAPD The Phenix refinement framework. CCP4 Newsletter 42Contribution 8: 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bardwell JCA, Mcgovern K, and Beckwith J. Identification of a protein required for disulfide bond formation in vivo. Cell 67: 581–589, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Battye T, Kontogiannis L, Johnson O, Powell HR, and Leslie AG. iMOSFLM: a new graphical interface for diffraction-image processing with MOSFLM. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 67: 271–281, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boucher HW, Talbot GH, Bradley JS, Edwards JE, Gilbert D, Rice LB, Scheld M, Spellberg B, and Bartlett J. Bad bugs, no drugs: no ESKAPE! An update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 48: 1–12, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brett PJ, Mah DCW, and Woods DE. Isolation and characterization of Pseudomonas pseudomallei flagellin proteins. Infect Immun 62: 1914–1919, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cegelski L, Marshall GR, Eldridge GR, and Hultgren SJ. The biology and future prospects of antivirulence therapies. Nat Rev Microbiol 6: 17–27, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC | Bioterrorism Agents/Diseases (by category) | Emergency Preparedness and response. www.bt.cdc.gov/agent/agentlist-category.asp Access date April2013

- 10.Chaowagul W. Recent advances in the treatment of severe melioidosis. Acta Trop 74: 133–137, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charney J, and Tomarelli RM. A colorimetric method for the determination of the proteolytic activity of duodenal juice. J Biol Chem 171: 501–505, 1947 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen VB, Arendall W, Headd JJ, Keedy DA, Immormino RM, Kapral GJ, Murray LW, Richardson JS, and Richardson DC. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66: 12–21, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng AC, and Currie BJ. Melioidosis: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev 18: 383–416, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chin CY, Othman R, and Nathan S. The Burkholderia pseudomallei serine protease MprA is autoproteolytically activated to produce a highly stable enzyme. Enzyme Microb Technol 40: 370–377, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chin CY, Tan SC, and Nathan S. Immunogenic recombinant Burkholderia pseudomallei MprA serine protease elicits protective immunity in mice. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2: 85, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chua KL, Chan YY, and Gan YH. Flagella are virulence determinants of Burkholderia pseudomallei. Infect Immun 71: 1622–1629, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chuaygud T, Tungpradabkul S, Sirisinha S, Chua KL, and Utaisincharoen P. A role of Burkholderia pseudomallei flagella as a virulent factor. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 102Suppl 1: S140–S144, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Currie BJ, Ward L, and Cheng AC. The epidemiology and clinical spectrum of melioidosis: 540 cases from the 20 year Darwin prospective study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 4: e900, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dailey FE, and Berg HC. Mutants in disulfide bond formation that disrupt flagellar assembly in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90: 1043–1047, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dutton RJ, Boyd D, Berkmen M, and Beckwith J. Bacterial species exhibit diversity in their mechanisms and capacity for protein disulfide bond formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105: 11933–11938, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edeling MA, Guddat LW, Fabianek RA, Halliday JA, Jones A, Thony-Meyer L, and Martin JL. Crystallization and preliminary diffraction studies of native and selenomethionine CcmG (CycY, DsbE). Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 57: 1293–1295, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ellman GL, Courtney KD, Andres V, and Featherstone RM. A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochem Pharmacol 7: 88–95, 1961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Emsley P, and Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 60: 2126–2132, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Erlanson DA. Introduction to fragment-based drug discovery. Top Curr Chem 317: 1–32, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Evans P. Scaling and assessment of data quality. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 62: 72–82, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gauthier YP, Thibault FM, Paucod JC, and Vidal DR. Protease production by Burkholderia pseudomallei and virulence in mice. Acta Trop 74: 215–220, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guzman LM, Belin D, Carson MJ, and Beckwith J. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose P-Bad promoter. J Bacteriol 177: 4121–4130, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ha UH, Wang YP, and Jin SG. DsbA of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is essential for multiple virulence factors. Infect Immun 71: 1590–1595, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hayashi S, Abe M, Kimoto M, Furukawa S, and Nakazawa T. The dsbA-dsbB disulfide bond formation system of Burkholderia cepacia is involved in the production of protease and alkaline phosphatase, motility, metal resistance, and multi-drug resistance. Microbiol Immunol 44: 41–50, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heras B, Shouldice SR, Totsika M, Scanlon MJ, Schembri MA, and Martin JL. DSB proteins and bacterial pathogenicity. Nat Rev Microbiol 7: 215–225, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heras B, Totsika M, Jarrott R, Shouldice SR, Guncar G, Achard ME, Wells TJ, Argente M, McEwan AG, and Schembri MA. Structural and functional characterization of three DsbA paralogues from Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium. J Biol Chem 285: 18423–18432, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hiniker A, and Bardwell JCA. In vivo substrate specificity of periplasmic disulfide oxidoreductases. J Biol Chem 279: 12967–12973, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hizukuri Y, Yakushi T, Kawagishi I, and Homma M. Role of the intramolecular disulfide bond in FlgI, the flagellar P-ring component of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 188: 4190–4197, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holden MTG, Titball RW, Peacock SJ, Cerdeno-Tarraga AM, Atkins T, Crossman LC, Pitt T, Churcher C, Mungall K, Bentley SD, Sebaihia M, Thomson NR, Bason N, Beacham IR, Brooks K, Brown KA, Brown NF, Challis GL, Cherevach I, Chillingworth T, Cronin A, Crossett B, Davis P, DeShazer D, Feltwell T, Fraser A, Hance Z, Hauser H, Holroyd S, Jagels K, Keith KE, Maddison M, Moule S, Price C, Quail MA, Rabbinowitsch E, Rutherford K, Sanders M, Simmonds M, Songsivilai S, Stevens K, Tumapa S, Vesaratchavest M, Whitehead S, Yeats C, Barrell BG, Oyston PCF, and Parkhill J. Genomic plasticity of the causative agent of melioidosis, Burkholderia pseudomallei. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101: 14240–14245, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holmgren A. Thioredoxin catalyzes the reduction of insulin disulfides by dithiothreitol and dihydrolipoamide. J Biol Chem 254: 9627–9632, 1979 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hopkins AL, and Groom CR. The druggable genome. Nat Rev Drug Discov 1: 727–730, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hu SH, Peek JA, Rattigan E, Taylor RK, and Martin JL. Structure of TcpG, the DsbA protein folding catalyst from Vibrio cholerae. J Mol Biol 268: 137–146, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huber-Wunderlich M, and Glockshuber R. A single dipeptide sequence modulates the redox properties of a whole enzyme family. Fold Des 3: 161–171, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Inaba K, Murakami S, Nakagawa A, Iida H, Kinjo M, Ito K, and Suzuki M. Dynamic nature of disulphide bond formation catalysts revealed by crystal structures of DsbB. EMBO J 28: 779–791, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Inaba K, Murakami S, Suzuki M, Nakagawa A, Yamashita E, Okada K, and Ito K. Crystal structure of the DsbB-DsbA complex reveals a mechanism of disulfide bond generation. Cell 127: 789–801, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Inglis TJJ, Robertson T, Woods DE, Dutton N, and Chang BJ. Flagellum mediated adhesion by Burkholderia pseudomallei precedes invasion of Acanthamoeba astronyxis. Infect Immun 71: 2280–2282, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jacobdubuisson F, Pinkner J, Xu Z, Striker R, Padmanhaban A, and Hultgren SJ. PapD chaperone function in pilus biogenesis depends on oxidant and chaperone like activities of DsbA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91: 11552–11556, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Korbsrisate S, Tomaras AP, Damnin S, Ckumdee J, Srinon V, Lengwehasatit I, Vasil ML, and Suparak S. Characterization of two distinct phospholipase C enzymes from Burkholderia pseudomallei. Microbiology 153: 1907–1915, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kurioka S, and Matsuda M. Phospholipase C assay using para-nitrophenylphosphorylcholine together with sorbitol and its application to studying metal and detergent requirement of enzyme. Anal Biochem 75: 281–289, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kurz M, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Jarrott R, Shouldice SR, Wouters MA, Frei P, Glockshuber R, O'Neill SL, Heras B, and Martin JL. Structural and functional characterization of the oxidoreductase alpha-DsbA1 from Wolbachia pipientis. Antioxid Redox Signal 11: 1485–1500, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Limmathurotsakul D, and Peacock SJ. Melioidosis: a clinical overview. Br Med Bull 99: 125–139, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Limmathurotsakul D, Wongratanacheewin S, Teerawattanasook N, Wongsuvan G, Chaisuksant S, Chetchotisakd P, Chaowagul W, Day NPJ, and Peacock SJ. Increasing incidence of human melioidosis in Northeast Thailand. Am J Trop Med Hyg 82: 1113–1117, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Logue CA, Peak IR, and Beacham IR. Facile construction of unmarked deletion mutants in Burkholderia pseudomallei using sacB counter-selection in sucrose-resistant and sucrose-sensitive isolates. J Microbiol Methods 76: 320–323, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Martin JL, Bardwell JCA, and Kuriyan J. Crystal structure of the Dsba protein required for disulfide bond formation in vivo. Nature 365: 464–468, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, and Read RJ. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Cryst 40: 658–674, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nelson JW, and Creighton TE. Reactivity and ionization of the active site cysteine residues of Dsba, a protein required for disulfide bond formation in vivo. Biochemistry 33: 5974–5983, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ngauy V, Lemeshev Y, Sadkowski L, and Crawford G. Cutaneous melioidosis in a man who was taken as a prisoner of war by the Japanese during World War II. J Clin Microbiol 43: 970–972, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Norville IH, Harmer NJ, Harding SV, Fischer G, Keith KE, Brown KA, Sarkar-Tyson M, and Titball RW. A Burkholderia pseudomallei macrophage infectivity potentiator like protein has rapamycin inhibitable peptidylprolyl isomerase activity and pleiotropic effects on virulence. Infect Immun 79: 4299–4307, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rasko DA, Moreira CG, Li DR, Reading NC, Ritchie JM, Waldor MK, Williams N, Taussig R, Wei S, Roth M, Hughes DT, Huntley JF, Fina MW, Falck JR, and Sperandio V. Targeting QseC signaling and virulence for antibiotic development. Science 321: 1078–1080, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ren G, Stephan D, Xu Z, Zheng Y, Tang D, Harrison RS, Kurz M, Jarrott R, Shouldice SR, Hiniker A, Martin JL, Heras B, and Bardwell JC. Properties of the thioredoxin fold superfamily are modulated by a single amino acid residue. J Biol Chem 284: 10150–10159, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sexton MM, Jones AL, Chaowagul W, and Woods DE. Purification and characterization of a protease from Pseudomonas pseudomallei. Can J Microbiol 40: 903–910, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shouldice SR, Heras B, Jarrott R, Sharma P, Scanlon MJ, and Martin JL. Characterization of the DsbA oxidative folding catalyst from Pseudomonas aeruginosa reveals a highly oxidizing protein that binds small molecules. Antioxid Redox Signal 12: 921–931, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shouldice SR, Heras B, Walden PM, Totsika M, Schembri MA, and Martin JL. Structure and function of DsbA, a key bacterial oxidative folding catalyst. Antioxid Redox Signal 14: 1729–1760, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stenson TH, and Weiss AA. DsbA and DsbC are required for secretion of pertussis toxin by Bordetella pertussis. Infect Immun 70: 2297–2303, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Suputtamongkol Y, Chaowagul W, Chetchotisakd P, Lertpatanasuwun N, Intaranongpai S, Ruchutrakool T, Budhsarawong D, Mootsikapun P, Wuthiekanun V, Teerawatasook N, and Lulitanond A. Risk factors for melioidosis and bacteremic melioidosis. Clin Infect Dis 29: 408–413, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Terwilliger TC, Adams PD, Read RJ, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Afonine PV, Zwart PH, and Hung LW. Decision-making in structure solution using Bayesian estimates of map quality: the PHENIX AutoSol wizard. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 65: 582–601, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Terwilliger TC, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Afonine PV, Moriarty NW, Zwart PH, Hung LW, Read RJ, and Adams PD. Iterative model building, structure refinement and density modification with the PHENIX AutoBuild wizard. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 64: 61–69, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Urban A, Leipelt M, Eggert T, and Jaeger KE. DsbA and DsbC affect extracellular enzyme formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 183: 587–596, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Valade E, Thibault FM, Gauthier YP, Palencia M, Popoff MY, and Vidal DR. The PmlI-PmlR quorum-sensing system in Burkholderia pseudomallei plays a key role in virulence and modulates production of the MprA protease. J Bacteriol 186: 2288–2294, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vellasamy KM, Vasu C, Puthucheary SD, and Vadivelu J. Comparative analysis of extracellular enzymes and virulence exhibited by Burkholderia pseudomallei from different sources. Microb Pathog 47: 111–117, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Walden PM, Heras B, Chen KE, Halili MA, Rimmer K, Sharma P, Scanlon MJ, and Martin JL. The 1.2 A resolution crystal structure of TcpG, the Vibrio cholerae DsbA disulfide-forming protein required for pilus and cholera-toxin production. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 68: 1290–1302, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Watarai M, Tobe T, Yoshikawa M, and Sasakawa C. Disulfide oxidoreductase activity of Shigella flexneri is required for release of Ipa proteins and invasion of epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92: 4927–4931, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.White NJ. Melioidosis. Lancet 361: 1715–1722, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wiersinga W, Currie BJ, and Peacock SJ. Melioidosis. N Engl J Med 367: 1035–1044, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Winn MD, Ballard CC, Cowtan KD, Dodson EJ, Emsley P, Evans PR, Keegan RM, Krissinel EB, Leslie AG, McCoy A, McNicholas SJ, Murshudov GN, Pannu NS, Potterton EA, Powell HR, Read RJ, Vagin A, and Wilson KS. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 67: 235–242, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wunderlich M, and Glockshuber R. In vivo control of redox potential during protein folding catalyzed by bacterial protein disulfide isomerase (Dsba). J Biol Chem 268: 24547–24550, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wuthiekanun V, Amornchai P, Saiprom N, Chantratita N, Chierakul W, Koh GC, Chaowagul W, Day NP, Limmathurotsakul D, and Peacock SJ. Survey of antimicrobial resistance in clinical Burkholderia pseudomallei isolates over two decades in Northeast Thailand. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55: 5388–5391, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhou YP, Cierpicki T, Jimenez RHF, Lukasik SM, Ellena JF, Cafiso DS, Kadokura H, Beckwith J, and Bushweller JH. NMR solution structure of the integral membrane enzyme DsbB: functional insights into DsbB catalyzed disulfide bond formation. Mol Cells 31: 896–908, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.