Abstract

Schisandra chinensis (SC), a traditional herbal medicine, has been prescribed for patients suffering from various liver diseases, including hepatic cancer, hypercholesterolemia, and CCl4-induced liver injury. We investigated whether SC extract has a protective effect on alcohol-induced fatty liver and studied its underlying mechanisms. Rats were fed with ethanol by intragastric administration every day for 5 weeks to induce alcoholic fatty liver. Ethanol treatment resulted in a significant increase in alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and hepatic triglyceride (TG) levels and caused fatty degeneration of liver. Ethanol administration also elevated serum TG and total cholesterol (TC) and decreased high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels. However, after administration of ethanol plus SC extracts, the ethanol-induced elevation in liver TC and TG levels was reversed. Elevation in serum TG was not observed after treatment with SC. Moreover, compared with the ethanol-fed group, the rats administered ethanol along with SC extracts for 5 weeks showed attenuated fatty degeneration and an altered lipid profile with decreased serum TC and TG, and increased HDL cholesterol levels. Chronic ethanol consumption did not affect peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) levels, but it decreased PPARα and phospho-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) levels in the liver. However, SC prevented the ethanol-induced decrease in PPARα expression and induced a significant decrease in sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1 expression and increase in phospho-AMPK expression in rats with alcoholic fatty liver. SC administration resulted in a significant decrease in intracellular lipid accumulation in hepatocytes along with a decrease in serum TG levels, and it reversed fatty liver to normal conditions, as measured by biochemical and histological analyses. Our results indicate that the protective effect of SC is accompanied by a significant increase in phospho-AMPK and PPARα expression in hepatic tissue of alcoholic rats, thereby suggesting that SC has the ability to prevent ethanol-induced fatty liver, possibly through activation of AMPK and PPARα signaling.

Key Words: : accumulation, alcoholic fatty liver, lipid AMPK, PPARα, Schisandra chinensis

Introduction

Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) can be broadly described as a condition with varying degrees of impairment of hepatic function following chronic and excessive ethanol consumption.1,2 An alcoholic fatty liver is characterized by varying amounts of lipid deposition in hepatocytes. Lipid deposition in more than 5% of hepatocytes causes fatty degeneration, while involvement of more than 50% of hepatocytes leads to fatty liver disease.3 Chronic alcohol consumption induces an increase in cellular nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide hydrate concentration and acetaldehyde dehydrogenase activity that leads to severe free fatty acid (FA) overload, triglyceride (TG) accumulation, and subsequent steatosis in hepatic tissue.4 With continued alcohol consumption, steatosis can progress to steatohepatitis, which has the potential to induce fibrosis, cirrhosis, and even hepatocellular carcinoma.5 Moreover, excess lipid accumulation in hepatic cells renders the liver more susceptible to injury by agents such as environmental pollutants and toxins, which are believed to be involved in the pathogenesis of alcoholic hepatitis.6 Therefore, it is important to understand the biochemical and molecular mechanisms that underlie liver fat accumulation and to understand how to modulate fat accumulation in the liver.

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is emerging as a metabolic master switch that regulates hepatic TG and cholesterol synthesis pathways.7 AMPK activation decreases de novo FA and triacylglycerol synthesis and increases β-oxidation. It phosphorylates and inhibits enzymes involved in lipid metabolism, including 3-hydroxy-3-methyl glutamate-CoA reductase and acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC).8 Inhibition of ACC directly decreases lipid synthesis and potentially accelerates FA oxidation by blocking the production of malonyl-CoA, which is an inhibitor of carnitine palmitoyltransferase I.9 Therefore, AMPK activation induces lipid catabolism and inhibits lipid deposition in liver.

Many studies have demonstrated that the effects of ethanol on lipid metabolism are caused by the inhibition of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα) and the stimulation of sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP)-1c, resulting in metabolic remodeling of the liver as a fat-storing rather than a fat-oxidizing organ.2,10 The regulation of lipid metabolism is also governed by an interaction between acute and circadian regulatory mechanisms, and the three PPARs (PPARα, PPARβ/δ, and PPARγ) play particularly important roles in these processes.10 Moreover, PPARα acts as a molecular sensor of endogenous FAs and regulates the transcription of the genes involved in lipid uptake and catabolism.8 Recent studies of the molecular mechanisms of alcoholic fatty liver development have revealed important information about therapeutic implications. Chronic ethanol consumption is associated with inhibition of AMPK and PPARα, two critical signaling molecules regulating hepatic FA oxidation pathways.11 The study also demonstrates that adiponectin exerts a protective effect against alcoholic liver steatosis by coordinating multiple signaling pathways mediated by AMPK, PPARα, and SREBP-1 leading to diminished lipogenesis, increased fat oxidation, and prevention of hepatic lipid accumulation.11

Recent studies have reported that in several Asian countries various herbal remedies are used for treatment of alcoholism patients. Although many natural products, such as Radix Pueraiae, Flos Puerariae, ginseng, mung bean, and dandelion are used to treat alcoholism safely and effectively, the lack of scientific evidence has restricted their application in clinical medicine.12,13 The previous study showed that Schisandra chinensis (SC) inhibited adipocyte differentiation and lipid accumulation in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes, and decreased body weight and fat tissue mass in high-fat diet induced-obese rats.14 SC contains Schisandrin B, the most abundant lignan of the dibenzocyclooctadiene type, which has been successfully used against toxic and viral hepatitis.15 Further pharmacological characterization of SC has revealed a wide range of pharmacological activities that include anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities. SC has been used to treat chronic coughs, excess perspiration, enuresis, chronic diarrhea, insomnia, and anxiety, which is accompanied by heart palpitations and diabetes caused by internal heat.16 In addition, Stacchiotti et al. have reported the beneficial effect of SC against mercury(II) chloride-induced hepatotoxicity in mice through increasing antioxidant potential and activating the stress response.15

Natural compounds are largely used in medicine to ameliorate fibrosis and hepatotoxicity because of their ability to facilitate the detoxification process. In the present study, we investigated the effects of SC extracts on the inhibition of alcohol-induced fatty liver in rats and examined the potential molecular mechanisms underlying this phenomenon.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of SC extract

The extracts of SC were prepared using a modified method reported by Park et al.14 Briefly, the powdered peel of SC (20 g) was extracted in 1000 mL of 80% ethanol at room temperature for 48 h. The liquid extract was filtered through chromatography paper (Whatman), evaporated in vacuo, and lyophilized to generate a powdered extract. Lyophilized SC powder was dissolved in distilled water at a concentration of 500 mg/mL and stored at −20°C for further use.

Total phenolic compounds, total flavonoids, and total anthocyanin content of SC extract

Total phenolic contents of the extracts were spectrophotometrically determined according to the Folin–Ciocalteu colorimetric method.17 Because quercetin is one of the polyphenol compounds, total phenolic content of ethanol extract of samples were expressed as micrograms of quercetin equivalents (CE)/gram. Total flavonoid was determined using the previous method with slight modifications.18 In brief, 0.25 mL of sample (100 μg/mL) was added to a tube containing 1 mL of double-distilled water. Next, 0.075 mL of 5% sodium nitrite, 0.075 mL of 10% aluminum chloride, and 0.5 mL of 1 M sodium hydroxide were added at 0, 5, and 6 min, sequentially. Finally, the volume of the reacting solution was adjusted to 2.5 mL with double-distilled water. The absorbance of the solution at a wavelength of 410 nm was detected using an Ultrospec 2100 pro spectrophotometers (Amersham Biosciences, Amersham, UK). Quercetin, a ubiquitous flavonoid present in many plant extracts, was used as the standard to quantify the total flavonoid content of hot water extract of the spice extracts. Results were expressed in micrograms of quercetin equivalents (QE)/gram. In the previous study, we quantitatively determined the contents of total flavonoid and phenolic compounds.14 Total anthocyanin content was measured at 520 nm in a spectrophotometer (Evolution 300 UV-VIS spectrophotometer) and estimated from a standard curve of purified cyanidin-3-O-xylosylrutinoside as a major pigment in SC.

Lignan contents of SC extract

The lignan contents of the SC were determined by high-performance liquid chromatography analysis using an Agilent Technologies 1200 series system equipped with an ultraviolet detector (Agilent Technologies). An ultrasphere octadecyl-silica column (5 μm, 4.6 mm×250 mm; Beckman Coulter) was used to separate the lignan components at a flow late of 1 mL/min. To analyze the content of various lignans in SC extracts, we used the following parameters: column temperature was maintained at room temperature throughout the analysis; the mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile-methanol-water (11:11:8, % v/v/v); run time was 50 min; detection wavelength was set at 254 nm; and the injection volume was 20 μL. Authentic schizandrin, gomisin A, and gomisin N were purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd. The lignan contents were identified as shown in Table 1 and these results were identical to those reported.19

Table 1.

Total Phenolic Compound, Total Flavonoid, Total Anthocyanin, and Major Lignan Contents of Schisandra chinensis Extracts

| Total phenolic compound | 139.50±13.79 (mg QE/g) |

| Total flavonoid | 119.71±3.09 (mg QE/g) |

| Total anthocyanin | 3.90±0.04 mg/g |

| Lignans | |

| Schizandrin | 6.7±0.03 mg/g |

| Gomisin A | 2.3±0.02 mg/g |

| Gomisin N | 3.3±0.02 mg/g |

Total phenolic acid and total flavonoid content expressed as milligrams of quercetin equivalent (QE)/g of extract. Values are mean±standard deviation (SD) (n=4).

Treatment of animals

The study protocol was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Gyeongsang National University (GNU-120613-R0049). Adult male Sprague–Dawley rats weighing ∼200–250 g were purchased from the Central Lab. Animal Inc. and housed under controlled environmental conditions. They were allowed free access to standard laboratory food (Central Lab. Animal Inc.). The room was exposed to 12 h periods of alternating light and dark. Rats were acclimatized to the experimental facility for 1 week prior to the start of the study. All rats were allowed free access to their respective diets and drinking water for 5 weeks. Three groups of rats (8 rats/group) were treated for 5 weeks before being sacrificed. Rats in the first group were fed a control diet and administered saline. Rats in the second group were intragastrically administered ethanol daily at a dose of 1 g/kg of body weight (BW). Rats in the third group were intragastrically administered ethanol (1 g/kg BW) plus SC (200 mg/kg BW). We were not able to measure food intake for individual rats because food was given in a common tray.

Biochemical analysis

Biochemical analysis was carried out using commercial kits. Blood was collected 12 h after the last ethanol administration. Serum levels of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were detected with a Dry-Chem chemistry analyzer (Fujifilm). Serum TG levels were enzymatically assayed using commercial kits (Asan Pharma, Co.). For determination of hepatic TG content, 250 mg of liver was homogenized in 4 mL of chloroform/methanol (2:1, v/v), and 1 mL of 50 mM sodium chloride was added to each sample. The samples were then centrifuged, and the organic layer was removed and dried. The resulting pellet was dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline containing 1% Triton X-100, and the TG content was determined using a commercially available enzymatic reagent kit (Asan Pharma, Co.). The concentrations of total cholesterol (TC) and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol were enzymatically assayed using commercial kits (Asan Pharma, Co.).

Histopathological examinations

Liver samples obtained at 12 h after the last ethanol administration were fixed in 4% phosphate-buffered 4% paraformaldehyde, then processed routinely, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned to 5 μm thickness. The sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated using standard techniques, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and examined by light microscopy.

Immunoblotting analysis

Western blotting was performed according to standard procedures. The total protein was separated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Amersham Pharmacia) by electroblotting. The membranes were blocked in 5% skim milk in TBST (0.05% Tween 20 in phosphate buffered saline). AMPK, PPARα, PPARγ, or SREBP-1 antibody were from Cell Signaling and the monoclonal β-actin antibody was from Chemicon. The blots were incubated overnight with the antibodies in TBST at 4°C. After incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody at room temperature, immunoreactive proteins were detected using a chemiluminescent an electrochemiluminescence assay kit (Amersham Pharmacia) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean±standard deviation. Significant difference among the treatment mean were determined using analysis of variance and Ducan's multiple range test at P<.05.

Results

Effects of SC on body and liver weight

The rats had free access to commercial food and tap water. The ethanol groups were administered ethanol orally for 5 weeks, while the control group was administered an equal volume of tap water. The gain in body weight of rats in all groups was compared at the end of 5 weeks. The ethanol and ethanol plus SC-administered groups showed slightly lower body weight gain compared with the normal diet-fed group (Table 2). The liver weights tended to be higher in ethanol- and ethanol plus SC-administered rats than in the normal diet-fed rats. The relative weight of the kidneys was not affected in the experimental groups (Table 2). The liver weight was the highest in the ethanol fed group, whereas the liver weight of the SC administered group lay between that of the normal diet-fed and the ethanol-administered group, indicating that hepatic lipid accumulation was inhibited in rats treated with SC.

Table 2.

Changes in Organ Weight of Rats Treated with Ethanol and Schisandra chinensis Extracts

| Groups | Body weight (gain) | Liver weight (g/100 g BW) | Kidney weight (g/100 g BW) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 157.23±6.78 | 3.28±0.27 | 0.83±0.027ns |

| Ethanol | 143.82±10.32* | 3.82±0.46* | 0.79±0.052ns |

| Ethanol+SC | 142.98±9.77* | 3.52±0.65* | 0.82±0.015ns |

Values are the mean±SD (n=8).

Normal: group fed normal diet; ethanol: group fed ethanol (1 g/kg BW); ethanol+SC: group fed ethanol (1 g/kg BW) plus SC (200 mg/kg BW).

P<.05 versus normal group.

Not significantly different among three groups (P>.05).

BW, body weight; SC, Schisandra chinensis.

Effects of SC on serum AST and ALT levels

Ethanol-induced liver injury was indicated by elevated serum AST and ALT levels. The results listed in Table 3 show the activities of serum AST and ALT in the various experimental groups. The ethanol-administered group showed significantly increased serum AST and ALT levels, but the SC extract-administered group exhibited no ethanol-induced increase of serum AST and ATL levels (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effects of Supplementation of Schisandra chinensis Extracts on Serum Aminotransferase Levels of Ethanol-Treated Rats

| Aminotransferase | ||

|---|---|---|

| Groups | AST (U/L) | ALT (U/L) |

| Normal | 88.5±15.1 | 53.2±11.5 |

| Ethanol | 228.4±32.3** | 93.2±15.7** |

| Ethanol+SC | 156.5±28.7* | 76.2±10.2* |

Values are the mean±SD (n=8).

P<.05, **P<.01 versus normal group.

AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase.

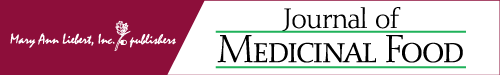

Effect of SC on serum and hepatic TG levels

In rats administered alcohol alone, the serum concentration of TG was 50% higher than that of normal diet fed rats, and SC administration remarkably decreased the levels of serum TG. Hepatic TG concentration in the ethanol-fed group was 25% higher compared with that of the normally fed group (Fig. 1A). Therefore, administration of alcohol-containing diets for 5 weeks caused the onset of fatty liver, but treatment with SC resulted in a significant decrease in TG to levels similar to those of control rats. These results demonstrated that administering SC protects against the development of alcoholic fatty liver in rat.

FIG. 1.

Effects of SC on the serum and hepatic TG levels (A), serum TC levels (B), and HDL cholesterol levels (C) in rats. Normal: group fed normal diet; ethanol: group fed ethanol (1 g/kg BW); ethanol+SC: group fed ethanol (1 g/kg BW) plus SC (200 mg/kg BW). Values are the mean±SD (n=8). **P<.01 versus normal; #P<.05 versus ethanol. SC, Schisandra chinensis; TG, triglyceride; BW, body weight; HDL, high-density lipoprotein.

Effect of SC on serum levels of TC and HDL cholesterol

The levels of TC significantly increased in the ethanol-fed group compared with normal diet-fed group, whereas TC concentration was significantly lowered by the consumption of SC. The ethanol-administered group showed a significant decrease in serum HDL cholesterol level compared with the control group. However, the SC-extract-administered group had a much smaller decrease in HDL cholesterol levels than the control group, but the difference was not statistically significant (Fig. 1B, C). Taken together, these results indicated that ethanol administration significantly increased serum and hepatic TG levels, whereas SC extract significantly suppressed the increase of the serum and hepatic TG levels.

Effects of SC on ethanol-induced fatty liver

Hepatic steatosis represents an excess accumulation of fat (TG) in hepatocytes. To assess the degree of fatty liver, we examined the accumulation of hepatic TG by H&E staining of rat liver. Ethanol administration caused degenerative morphological change exhibited by fat droplets in liver sections in the liver. Cytoplasmic microvacuolation of centrilobular hepatocytes was observed more frequently in the ethanol-fed group compared with the SC-fed group (Fig. 2). Inversely, lipid droplets and hepatocellular ballooning degeneration were significantly inhibited in the SC-treated liver. This was consistent with the alterations in levels of hepatic lipids. These results demonstrated that SC treatment remarkably improved the ethanol-induced changes in liver histopathology.

FIG. 2.

Effect of SC on hepatic pathological changes. Liver histology in rats treated with ethanol or ethanol plus SC. The major histopathological change induced by alcohol in rat liver was microvesicular steatosis. SC treatment suppressed the ethanol-induced alterations, with diminished fatty infiltration and minimal steatosis. Hematoxylin and eosin, 200×. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/jmf

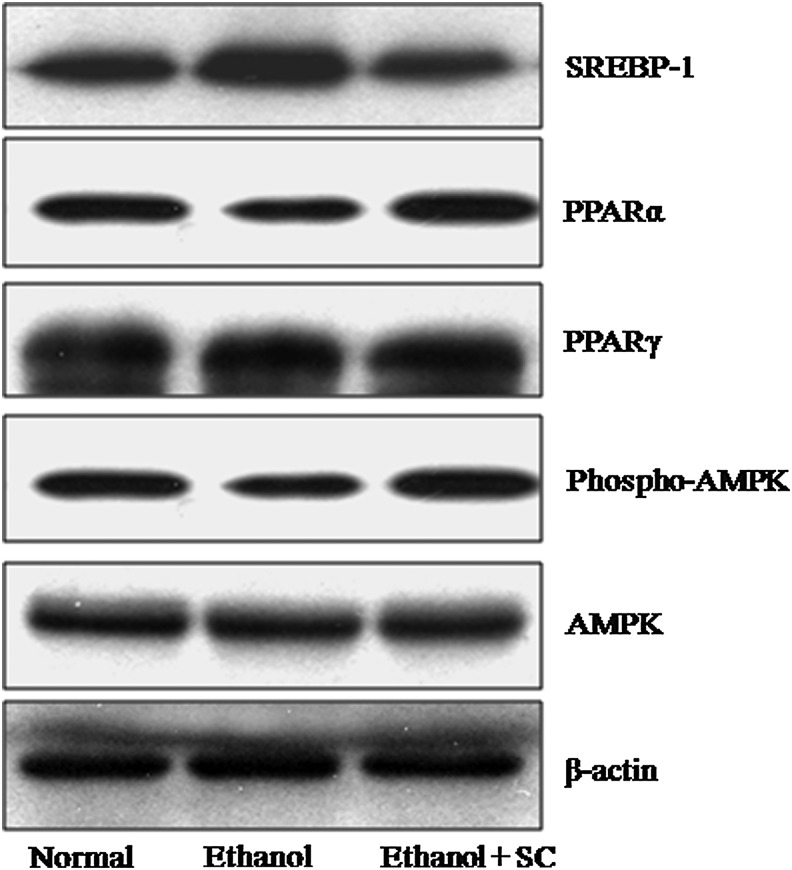

Effect of SC on the expression of hepatic genes related to alcoholic fatty liver

The regulation of several hepatic genes implicated in the development of alcoholic fatty liver was evaluated through Western blot analyses (Fig. 3). First, the effect of SC on AMPK activation was tested in ethanol-fed rats. The levels of phospho-AMPK were significantly decreased upon ethanol feeding compared with the control group but were dramatically increased by SC treatment. Total AMPK was expressed at similar levels in all groups. The expression level of SREBP-1 was decreased in the livers of SC-treated rats compared with that of the ethanol-fed and control groups. Chronic alcohol administration significantly reduced the expression of PPARα, which is involved in lipid metabolism in the liver. However, the ethanol-induced downregulation of PPARα was reversed by SC feeding. The expression level of PPARγ in the SC-treated group was almost unchanged compared with that of the control or ethanol-fed groups (Fig. 3). These data indicate that chronic ethanol administration did not affect the expression of PPARγ gene, but it decreased PPARα levels in the liver. Together, however, SC prevented this ethanol-induced decrease in PPARα levels and phospho-AMPK levels.

FIG. 3.

Effect of SC on the expression of SREBP-1, AMPK, PPARα, and PPARγ in the liver. The representative Western blots from one of three independent experiments are shown. SC administration downregulated hepatic SREBP-1 and upregulated PPARα and phospho-AMPK expression in ethanol-fed rats. SREBP-1, sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1; AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor.

Discussion

ALD is a major cause of illness and death. Alcoholic fatty liver is characterized by variable deposition of lipids in the hepatocytes. Fatty degeneration of the liver is induced by the deposition of fat in more than 5% of the hepatocytes. This accumulation of fat in the hepatocytes leads to the development of fatty liver (steatosis), which progresses to hepatitis and fibrosis and finally leads to liver cirrhosis.3

In the present study, we investigated whether SC can protect against fatty liver disease in rats chronically fed ethanol. Our results show that chronic ethanol feeding causes hepatic steatosis as evidenced by elevation of serum ALT and AST, accumulation of hepatic TG and TC, and morphologic changes (small lipid droplets and hydropic degeneration of hepatocytes) in the liver. Importantly, we found that SC administration significantly protects against ethanol-induced fatty liver by reducing elevated serum ALT and AST levels, decreasing lipid levels in the serum and hepatic tissue, and alleviating hepatic lipid accumulation.

SC is a popular herb in traditional oriental medicine; its extracts inhibit preadipocyte differentiation and adipogenesis in cultured cells, leading to decreased body weight and fat tissue mass in high-fat diet-induced obese rats.14 Interestingly, Na et al. have isolated dibenzocylooctadiene lignans from SC, which inhibit FA synthetase.20 The lignans from SC also exert hepatoprotective effects against chronic liver injury in rats.21 Moreover, several recent experimental studies reported its beneficial effect against aging-related liver changes and hepatic hypercholesterolemia.22,23

The accumulation of fat in the liver essentially results from alcohol-induced pathogenic processes, which include an increase in uptake of free FAs, synthesis of free FAs, and a decrease in β-oxidation of free FAs.24 These results demonstrate that ethanol administration increases lipid droplet accumulation in hepatocytes, and significantly increases serum and hepatic TG levels. Feeding the animals SC along with ethanol suppresses the increase of fat accumulation in hepatocytes and hepatocellular ballooning degeneration. In addition, the ethanol-induced increase in TG levels in serum and hepatic tissue was significantly suppressed by SC administration.

It is established that AST can be found in the liver, cardiac muscle, skeletal muscle, kidney, pancreas, leukocytes, and erythrocytes, whereas ALT is present only in the liver.25 Therefore, ALT is a reliable marker for detecting liver injury.26 When a hepatocyte is injured, its plasma membrane is disrupted, leading to the leakage of enzymes into the extracellular fluid, which can then be detected in the serum.27 Increased levels of AST and ALT in the serum, therefore, indicate increased damage and/or necrosis of hepatocytes.28 In this study, we demonstrate that ethanol administration elevates serum AST and ALT levels, whereas SC co-administration significantly decreases the level of these enzymes in the serum, suggesting a decrease in liver cell damage. Therefore, our data show that SC has robust hepatoprotective effects.

Cholesterol is a chemical compound that is a combination of lipid and steroid and is naturally produced by the body. About 80% of the body's cholesterol is produced by and stored in the liver. The liver is able to regulate cholesterol levels in the blood stream and can secrete cholesterol if it is needed by the body.29 In the present study, we show that chronic ethanol consumption significantly increased serum TC and decreased serum HDL cholesterol levels. However, SC administration resulted in decreased total serum cholesterol levels compared with that of the control (ethanol treated) group. In addition, SC-fed rats showed serum HDL cholesterol levels similar to that of the normal group.

Alcoholic fatty liver is characterized by increased concentrations of TG as a result of impaired FA catabolism due to inhibition of PPARα and due to increased lipogenesis in the liver as a result of activation of the AMPK pathway.30,31 We examined the effect of SC on PPARα gene expression in rat liver tissue. Ethanol administration decreased PPARα gene expression, leading to inhibition of FA oxidation. SC treatment increased the expression of PPARα gene but did not alter PPARγ levels. This suggests that the potential mechanism underlying the protection of ethanol-induced fatty liver by SC likely involves the restoration of PPARα function. Ethanol-induced PPARγ-dependent activation of lipogenesis in the liver is not affected by SC. In addition to PPARα, SREBP-1 plays an important role to activate the genes that encode the enzymes involved in FA synthesis, such as ACC, FAS, and SCD1, and drives the formation of TG.32 In this study, the increased expression of SREBP-1 in ethanol-exposed rats was significantly inhibited by SC treatment, indicating that the protective effects of SC might be related with the modulation of SREBP-1.

Next, we investigated whether SC affects the AMPK signaling pathway to inhibit fatty liver formation in ethanol-fed rats. AMPK is known to play a major role in glucose regulation and lipid metabolism and in controlling metabolic disorders such as diabetes, obesity, and liver hepatitis.7 This study shows that SC treatment results in increased AMPK phosphorylation, which occurs at a much lower level in chronic ethanol-induced liver. This is consistent with the observation that dysregulation of hepatic AMPK signaling in response to chronic ethanol exposure is a crucial mechanism for the development of alcoholic fatty liver. Once activated, AMPK stimulates ATP-generating cellular events, such as glucose uptake and lipid oxidation, to produce energy, while turning off energy-consuming processes, such as glucose and lipid production, to restore energy balance.33 The ethanol-mediated inhibition of AMPK was associated with enhanced ACC activity, increased malonyl-CoA concentrations, and the development of liver steatosis. Altogether, our data indicate that ethanol-induced lipid accumulation and development of fatty liver is reversed by SC via activation of AMPK.

In the present study, we demonstrated that ethanol administration results in an increase in intracellular lipid accumulation in hepatocytes along with increased serum TG content. Histopathological examination of the liver from the animals demonstrated that the number of fatty hepatocytes was significantly increased upon chronic alcohol consumption but returned to normal levels in animals that were also administered SC. These results demonstrate that the alcohol-induced hepatic pathological changes were significantly inhibited in SC-fed rats. Taken together, SC treatment suppresses the increase of lipid accumulation in hepatocytes and hepatocellular ballooning degeneration in the liver. Moreover, treatment of rats with SC for 5 weeks reverses fatty liver to the normal condition, as determined biochemically and histologically.

Therefore, the present study strongly indicates that SC has protective effects against alcohol-induced fatty liver in rats. The cellular mechanisms behind ALD involve close associations of PPARα, SREBP-1, and AMPK and the potential development of steatosis in the liver, but this was mitigated by SC. In conclusion, administration of SC diminishes the accumulation of alcohol-derived lipids in the liver. These results suggest that administration of SC may be useful in preventing and improving fatty liver induced by alcohol.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education, Basic Science Research Program, National Research Foundation, Korea (No. 20120008419) and Korea Grant funded by the Korean government (MEST; No. 2012 R1A 2A2 A06045015).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Sozio MS, Liangpunsakul S, Crabb D: The role of lipid metabolism in the pathogenesis of alcoholic and nonalcoholic hepatic steatosis. Semin Liver Dis 2010;30:378–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.You M, Crabb DW: Recent advances in alcoholic liver disease II. Minireview: molecular mechanisms of alcoholic fatty liver. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2004;287:1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tannapfel A, Denk H, Dienes HP, Langner C, Schirmacher P, Trauner M, Flott-Rahmel B: Histopathological diagnosis of non-alcoholic and alcoholic fatty liver disease. Virchows Arch 2011;458:511–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stickel F, Seitz HK: Alcoholic steatohepatitis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2010;24:683–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Purohit V, Gao B, Song BJ: Molecular mechanisms of alcoholic fatty liver. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2009;33:191–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anstee QM, Daly AK, Day CP: Genetics of alcoholic and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Semin Liver Dis 2011;31:128–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tao R, Gong J, Luo X, Zang M, Guo W, Wen R, Luo Z: AMPK exerts dual regulatory effects on the PI3K pathway. J Mol Signal 2010;18:1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reddy JK, Rao MS: Lipid metabolism and liver inflammation. II. Fatty liver disease and fatty acid oxidation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2006;290:852–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rogers CQ, Ajmo JM, You M: Adiponectin and alcoholic fatty liver disease. IUBMB Life 2008;60:790–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moriya T, Naito H, Ito Y, Nakajima T: “Hypothesis of seven balances”: molecular mechanisms behind alcoholic liver diseases and association with PPARα. J Occup Health 2009;51:391–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.You M, Considine RV, Leone TC, Kelly DP, Crabb DW: Role of adiponectin in the protective action of dietary saturated fat against alcoholic fatty liver in mice. Hepatology 2005;42:568–577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang HF, Lin YH, Chu CC, Wu SJ, Tsai YH, Chao JC: Protective effects of Ginkgo biloba, Panax ginseng, and Schizandra chinensis extract on liver injury in rats. Am J Chin Med 2007;35:995–1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chien CF, Wu YT, Tsai TH: Biological analysis of herbal medicines used for the treatment of liver diseases. Biomed Chromatogr 2011;25:21–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park HJ, Cho JY, Kim MK, Koh PO, Cho KW, Kim CH, Lee KS, Chung BY, Kim GS, Cho JH: Anti-obesity effect of Schisandra chinensis in 3T3-L1 cells and high fat diet-induced obese rats. Food Chem 2012;134:227–234 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stacchiotti A, Li Volti G, Lavazza A, Rezzani R, Rodella LF: Schisandrin B stimulates a cytoprotective response in rat liver exposed to mercuric chloride. Food Chem Toxicol 2009;47:2834–2840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wagner H, Bauer R, Peigen X, Jianming C, Nenninger A: Fructus Schisandrae (Wuweizi). In: Chinese Drug Monographs and Analysis. Wǘhr E, ed.). Verlag fǘr Ganzheitliche Medizin: Kő;tzting, 1996, pp. 467–489 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu X, Yu X, Jing H: Optimization of phenolic antioxidant extraction from Wuweizi (Schisandra chinensis) pulp using random-centroid optimization methodology. Int J Mol Sci 2011;12:6255–6266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meda A, Lamien CE, Romito M, Millogo J, Nacoulma OG: Determination of the total phenolic, flavonoid and proline contents in Burkina Fasan honey, as well as their radical scavenging activity. Food Chem 2005;91:571–577 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song Y, Lee SJ, Park HJ, Jang SH, Chung BY, Song YM, Kim GS, Cho JH: Improvement effect of Schisandra chinensis on high-fat diet-induced fatty liver in rats. Korean J Vet Service 2013;36:45–52 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Na M, Hung TM, Oh WK, Min BS, Lee SH, Bae K: Fatty acid synthase inhibitory activity of dibenzocyclooctadiene lignans isolated from Schisandra chinensis. Phytother Res 2010;24:S225–S228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yan F, Zhang QY, Jiao L, Han T, Zhang H, Qin LP, Khalid R: Synergistic hepatoprotective effect of Schisandrae lignans with Astragalus polysaccharides on chronic liver injury in rats. Phytomedicine 2009;16:805–813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chiu PY, Leung HY, Poon MK, Ko KM: Chronic schisandrin B treatment improves mitochondrial antioxidant status and tissue heat shock protein production in various tissues of young adult and middle-aged rats. Biogerontology 2006;7:199–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pan SY, Dong H, Zhao XY, Xiang CJ, Fang HY, Fong WF, Yu ZL, Ko KM: Schisandrin B from Schisandra chinensis reduces hepatic lipid contents in hypercholesterolaemic mice. J Pharm Pharmacol 2008;60:399–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burt AD, Mutton A, Day CP: Diagnosis and interpretation of steatosis and steatohepatitis. Semin Diagn Pathol 1998;15:246–258 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rej R: Aspartate aminotransferase activity and isoenzymes proportions in human liver tissue. Clin Chem 1978;24:1971–1979 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gross A, Ong TR, Grant R, Hoffmann T, Gregory DD, Sreerama L: Human aldehyde dehydrogenase-catalyzed oxidation of ethylene glycol ether aldehydes. Chem Biol Interact 2009;178:56–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hennes HM, Smith DS, Schneider K, Hegenbarth MA, Duma MA, Jona JZ: Elevated liver transaminase levels in children with blunt abdominal trauma: a predictor of liver injury. Pediatrics 1990;86:87–90 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldberg DM, Watts C: Serum enzyme changes as evidence of liver reaction to oral alcohol. Gastroenterology 1965;49:256–261 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kwon HJ, Kim YY, Choung SY: Amelioration effects of traditional Chinese medicine on alcohol-induced fatty liver. World J Gastroenterol 2005;11:5512–5516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qin Y, Tian YP: Exploring the molecular mechanisms underlying the potentiation of exogenous growth hormone on alcohol-induced fatty liver diseases in mice. J Transl Med 2010;8:120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wada S, Yamazaki T, Kawano Y, Miura S, Ezaki O: Fish oil fed prior to ethanol administration prevents acute ethanol-induced fatty liver in mice. J Hepatol 2008;49:441–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shimano H, Horton JD, Shimomura I, Hammer RE, Brown MS, Goldstein JL: Isoform 1c of sterol regulatory element binding protein is less active than isoform 1a in livers of transgenic mice and in cultured cells. J Clin Invest 1997;99:846–854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Winder WW, Hardie DG: AMP-activated protein kinase, a metabolic master switch: possible roles in type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol 1999;277:E1–E10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]