Abstract

Aims: Protein S-bacillithiolation was recently discovered as important thiol protection and redox-switch mechanism in response to hypochlorite stress in Firmicutes bacteria. Here we used transcriptomics to analyze the NaOCl stress response in the mycothiol (MSH)-producing Corynebacterium glutamicum. We further applied thiol-redox proteomics and mass spectrometry (MS) to identify protein S-mycothiolation. Results: Transcriptomics revealed the strong upregulation of the disulfide stress σH regulon by NaOCl stress in C. glutamicum, including genes for the anti sigma factor (rshA), the thioredoxin and MSH pathways (trxB1, trxC, cg1375, trxB, mshC, mca, mtr) that maintain the redox balance. We identified 25 S-mycothiolated proteins in NaOCl-treated cells by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), including 16 proteins that are reversibly oxidized by NaOCl in the thiol-redox proteome. The S-mycothiolome includes the methionine synthase (MetE), the maltodextrin phosphorylase (MalP), the myoinositol-1-phosphate synthase (Ino1), enzymes for the biosynthesis of nucleotides (GuaB1, GuaB2, PurL, NadC), and thiamine (ThiD), translation proteins (TufA, PheT, RpsF, RplM, RpsM, RpsC), and antioxidant enzymes (Tpx, Gpx, MsrA). We further show that S-mycothiolation of the thiol peroxidase (Tpx) affects its peroxiredoxin activity in vitro that can be restored by mycoredoxin1. LC-MS/MS analysis further identified 8 proteins with S-cysteinylations in the mshC mutant suggesting that cysteine can be used for S-thiolations in the absence of MSH. Innovation and Conclusion: We identified widespread protein S-mycothiolations in the MSH-producing C. glutamicum and demonstrate that S-mycothiolation reversibly affects the peroxidase activity of Tpx. Interestingly, many targets are conserved S-thiolated across bacillithiol- and MSH-producing bacteria, which could become future drug targets in related pathogenic Gram-positives. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 20, 589–605.

Introduction

Low molecular weight (LMW) thiols play essential roles as redox buffers in the defense against Reactive oxygen species (ROS) to maintain the reduced state of the cytoplasm (58). Eukaryotes and Gram-negative bacteria produce glutathione (GSH) as LMW thiol redox buffer. Among the Gram-positive bacteria, Firmicutes utilize as thiol redox buffer bacillithiol (Cys-GlcN-Mal, BSH) (19, 41) and Actinomycetes produce the related redox buffer mycothiol (AcCys-GlcN-Ins, MSH) (39). MSH is involved in the detoxification of ROS, toxins and antibiotics and MSH-deficient mutants are very sensitive to thiol-reactive compounds (40). ROS cause reversible oxidations of protein thiols to intra- or intermolecular disulfides, and to mixed disulfides with LMW thiols (S-thiolations) (1).

Innovation.

We have studied the transcriptome and redox proteome under NaOCl stress in the mycothiol (MSH)-producing model bacterium Corynebacterium glutamicum. Using liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis and redox proteomics we provide for the first time evidence that protein S-mycothiolation is a widespread protein protection mechanism under NaOCl stress in Actinomycetes. The S-mycothiolome includes proteins that function in the glycolysis, biosynthesis of methionine, glycogen, nucleotides, thiamine, protein translation, and antioxidant functions, including striking conservation of some S-thiolated proteins (e.g., Tuf, MetE, GuaB) across Gram-positive bacteria. We further show that the S-mycothiolated peroxidase Tpx is inactive and reactivated by the Mrx1/MSH/Mtr electron pathway in vitro.

In eukaryotes, protein S-glutathionylation has emerged as major redox-regulatory mechanism that controls the activity of redox sensing transcription factors and protects active site cysteine (Cys) residues from irreversible oxidation to sulfonic acids (8). Many eukaryotic proteins, like α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase, ornithine δ-aminotransferase, pyruvate kinase, heat specific chaperones, and regulatory proteins (c-Jun, NF-κB) are reversibly inactivated or activated by S-glutathionylation (8, 24). However, little is known about the regulatory role of protein S-thiolation for bacterial physiology. We have recently identified protein S-bacillithiolations as mixed BSH protein disulfides in response to NaOCl stress in Bacillus and Staphylococcus species (7). Protein S-bacillithiolation controls redox-sensing regulators and protects active site Cys residues of essential and conserved metabolic enzymes from overoxidation. The redox-sensing MarR-family OhrR repressor is inactivated by S-bacillithiolation after NaOCl stress resulting in upregulation of the OhrA peroxiredoxin (Prx) that confers NaOCl resistance (6, 29). Mass spectrometry identified 54 S-bacillithiolated proteins in different Bacillus and Staphylococcus species that include 29 unique proteins and 8 conserved proteins. The S-bacillithiolated proteins function as metabolic enzymes in biosynthetic pathways for amino acids (methionine, branched chain and aromatic amino acids), cofactors, nucleotides; or as translation factors, chaperones, redox, and antioxidant proteins (7). The methionine synthase MetE is the most abundant S-bacillithiolated protein in Bacillus species under NaOCl stress. S-bacillithiolation of MetE occurs in its active site Zn center leading to enzyme inactivation and methionine auxotrophy (6). Since amino acid biosynthetic enzymes and translation factors are conserved in the S-bacillithiolome among Firmicutes, we propose that S-bacillithiolation could function in redox-regulation of protein synthesis.

Protein disulfides and S-thiolations are reversible Cys oxidations that are reduced by the thioredoxin (Trx)/thioredoxin reductase (TrxR) system or by the glutaredoxin (Grx)/GSH/glutathione disulfide reductase system in Escherichia coli (15). The Trx system is involved in reduction of inter- and intramolecular protein disulfides and the Grx proteins catalyze de-glutathionylation of S-glutathionylated proteins. In Actinomycetes, a Grx-like mycoredoxin1 (Mrx1) with a CGYC active site motif has been structurally and biochemical characterized. Mrx1 reduces a MSH mixed ß-hydroxyethyl disulfide (HED) and exclusively uses the MSH/Mtr/NADPH electron pathway (57). Corynebacterium glutamicum serves as model for pathogenic Actinomycetes, such as Corynebacterium diphtheriae and Mycobacterium tuberculosis and is also of biotechnological importance. The disulfide stress response in Actinomycetes is controlled by the ECF sigma factor σR in Streptomycetes coelicolor or its σH homolog in C. glutamicum (26). σR or σH are sequestered at control conditions by their cognate redox-sensitive anti sigma factors, RsrA or RshA, respectively in S. coelicolor or C. glutamicum. Redox-regulation has been shown for the RsrA/σR system in S. coelicolor. RsrA senses disulfide stress by oxidation of the Zn-binding Cys residues leading to Zn release and free σR(1). The RshA/σHsystem of C. glutamicum controls genes for the Trx/TrxR system (trxB, trxB1, trxC), for MSH biosynthesis and recycling (mshC, mca) and for the mycothiol disulfide (MSSM) reductase (mtr) (3, 11). The regulation of the Trx/TrxR and MSH pathways by RsrA/σR or RshA/σH homologs is conserved among Actinomycetes (1, 26, 45).

However, nothing is known about proteins that are redox-controlled or protected by protein S-mycothiolation under ROS stress conditions in Actinomycetes. Thus, we applied here transcriptomics, redox proteomics, and mass spectrometry (MS) to analyze the NaOCl-stress response and proteome-wide protein S-mycothiolations in the MSH-producing C. glutamicum.

Results

NaOCl-stress elicits a RshA/σH disulfide stress response in C. glutamicum

Previously, we identified protein S-bacillithiolation by sub-lethal NaOCl concentrations in Firmicutes bacteria (7). To optimize the conditions for protein S-mycothiolation, the MSH-producing C. glutamicum ATCC13032 wild type was grown in minimal medium and treated with sub-lethal NaOCl concentrations that reduced the growth rate about half-maximal. Treatment of exponentially growing C. glutamicum cells with 180 μM NaOCl at an optical density at 500 nm (OD500) of 8.0 resulted in a slower growth compared to untreated cells (Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/ars), but cells are still able to grow and reached the stationary phase after 5–6 h. Next, we applied DNA microarray analyses to analyze if NaOCl stress causes a disulfide stress response in C. glutamicum as shown for Bacillus subtilis (6). Transcriptome analyses of C. glutamicum wild-type cells were performed after treatment with 180 μM NaOCl for 10 and 30 min. The transcriptome data revealed that 224 and 411 genes are at least twofold induced and 325 and 472 genes are at least twofold repressed by NaOCl stress (p-values<0.05) in two biological replicates after 10 and 30 min of NaOCl stress, respectively (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). This indicates that 7.3% and 13.5% of the genome (3052 genes) were twofold induced after 10 and 30 min NaOCl stress, respectively, while 10.6% and 15.5% showed twofold reduced transcription.

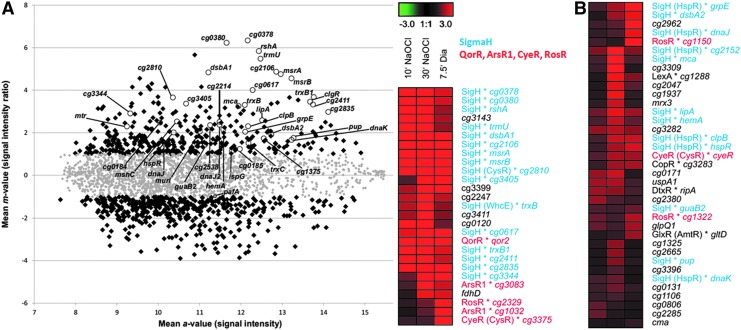

The changes in the C. glutamicum transcriptome in response to disulfide-stress provoked by diamide were previously published (3, 11). To visualize the overlaps in the gene expression profiles between NaOCl and diamide stress, we performed a hierarchical clustering analysis. The cluster analysis revealed a strong upregulation of the disulfide stress σH regulon by both diamide and NaOCl (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. S2, Supplementary Table S3). About 40 genes of the σH regulon were 2–80-fold induced by NaOCl stress that are labeled in the Heat map and Scatter plot in Figure 1. The rshA gene encoding the anti sigma factor for σH was most strongly upregulated by NaOCl stress (22–47-fold). In addition, NaOCl stress caused strong inductions of the σH-regulon genes for thioredoxins trxB1 (10–13-fold), trxC (3-fold), cg1375 (3-fold), the thioredoxin reductase trxB (4–10-fold), dsbA-like thiol-disulfide oxidoreductases cg2838 or dsba1(15–29-fold), cg2661 or dsba2 (2–4-fold), and two methionine sulfoxide reductases msrA and msrB (12–15-fold). The σH-regulon genes for MSH biosynthesis, recycling and reduction were also upregulated, including the Cys ligase mshC (6-fold), the MSH-S-conjugate amidase mca (3–10-fold) and the MSSM reductase mtr (2–5-fold). Most strongly induced were the σH-dependent phage-associated gene cg0378 (50–80-fold) and the tRNA-(5-methylaminomethyl-2-thiouridylate)-methyltransferase gene cg1397 (17–45-fold). The σH-regulon also integrates the ClgR and HspR heat-shock regulons that control chaperones and proteases of the protein quality control machinery (3, 11). The genes of the ClgR-regulon (clgR, clpP2, dnaJ2) and HspR regulon (hspR, dnaK, clpB) were 2–11-fold induced by NaOCl stress.

FIG. 1.

Microarray intensity scatter plot (A) and hierarchical clustering analysis of the Corynebacterium glutamicum transcriptome after NaOCl stress indicates a σH-dependent disulfide stress response (B). (A) Ratio/intensity scatter plot of the C. glutamicum wild type transcriptome 30 min after NaOCl stress. Genes with at least twofold expression changes after NaOCl stress are marked with black squares, including σH-dependent genes that are labeled with circles. (B) Hierarchical clustering analysis of NaOCl and diamide induced gene expression profiles was performed using GENESIS (55). The transcriptome data sets included genes with at least twofold expression changes at 7.5 min after 2 mM diamide, 10 and 30 min after 180 μM NaOCl stress (Supplementary Tables S1–S3). Red indicates induction and green repression by NaOCl and diamide stress. The σH-regulon is blue-labeled and the redox-sensing QorR, ArsR1, CyeR, and RosR-regulons are red-labeled. The complete Heatmap is shown in Supplementary Figure S2. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

In addition, other redox-sensing regulators respond to NaOCl stress. The MarR/DUF24-family regulator QorR is a redox sensor for disulfide stress (10) and controls the quinone reductase-encoding qorA gene that was 10-fold induced by NaOCl stress (Fig. 1, Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). The ArsR-family transcription factors CyeR, ArsR1 and ArsR2 are three- to fivefold induced by NaOCl stress that control metal ion efflux pumps, arsenate reductases and NADPH-dependent flavin oxidoreductases. ArsR1 (Cg3082) controls cg3083, encoding a putative secondary Co2+/Zn2+/Cd2+ efflux transporter of the cation diffusion facilitator family that was 10-fold induced by NaOCl. ArsR2 regulates an arsenate reductase (arsX or cg0319) that reduces arsenate to arsenite and an arsenite efflux pump (arsC1 or cg0318) (60) that are 2-fold upregulated by NaOCl. RosR is a thiol-based peroxide-sensing MarR-family repressor (4) and the RosR-controlled genes for flavin oxidoreductases cg1150 and cg2329 are 2-fold induced by NaOCl. Furthermore, the hmp gene is 19-fold upregulated by NaOCl stress, which encodes a flavohemoglobin for nitric oxide detoxification. The hmp gene is under control of the NsrR regulator in E. coli and Streptomyces that senses nitrosative stress by an FeS cluster, but transcriptional regulation of hmp is unknown in C. glutamicum (59). It is further interesting to note, that no typical oxidative stress defense genes were induced by NaOCl stress, such as genes for the catalase (kat) or alkyl hydroperoxide reductase ahpC that are controlled by OxyR in the related C. diphtheriae (25).

Thiol-redox proteomics identifies 30 NaOCl-sensitive proteins in C. glutamicum

Next, we used our fluorescent-label redox proteomics approach to quantify the level of reversible thiol oxidation versus the protein amounts for 45 proteins after NaOCl stress in the C. glutamicum wild type and in the mshC mutant (Figs. 2 and 3, Supplementary Table S4). The wild type and mshC mutant were chosen for the comparison of the redox proteomes to identify possible S-mycothiolated proteins in the wild type. For redox proteomics, untreated and NaOCl-exposed cells were harvested in urea/thiourea buffer in the presence of 100 mM iodoacetamide (IAM) to alkylate all reduced thiols. Proteins with reversible thiol-oxidations, including S-thiolations were reduced with Tris-(2-carboxyethyl)-phosphine (TCEP) and labeled with the fluorescent dye BODIPY FL C1-IA. The fluorescent image was overlaid with the Coomassie-stained protein amount image and the fluorescence/protein amount ratios were quantified using the Decodon software as level of reversible thiol oxidations. Proteins with basal level oxidation include the Prx Bcp (3–5-fold redox ratios) and the thiol peroxidase (Tpx) (7–10-fold redox ratios) that form intramolecular disulfides during their peroxide detoxification cycle (36). Further conserved redox-sensitive proteins with basal oxidations include the dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase Lpd (PdhD homolog) and the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase GapA in C. glutamicum that are also oxidized to intramolecular disulfides (6).

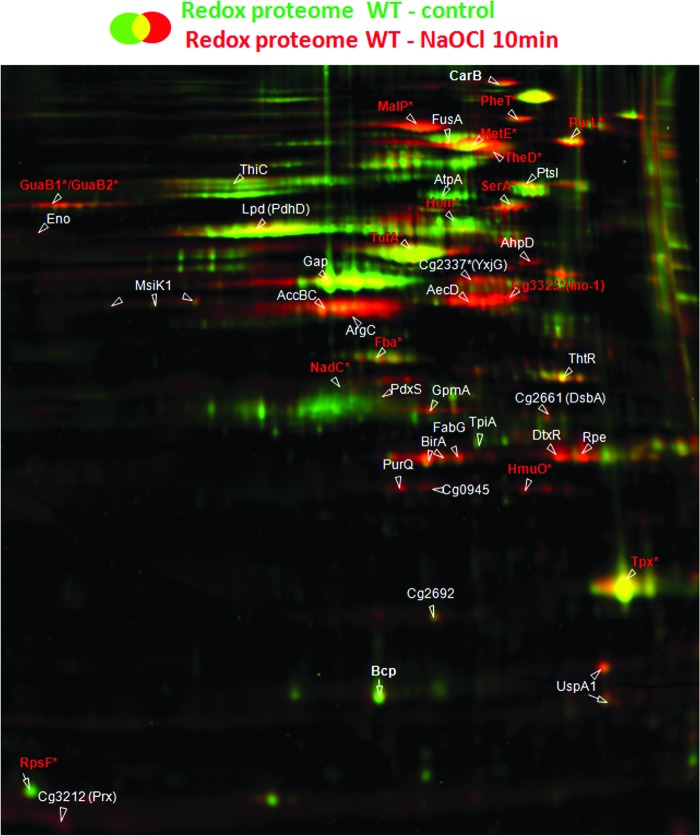

FIG. 2.

NaOCl-stress causes strongly increased reversible thiol-oxidations in the redox proteome of the C. glutamicum wild type. The redox proteome of C. glutamicum wild type at control conditions (green image) was overlaid with that of cells exposed to 180 μM NaOCl-stress (red image). For redox proteomics, reduced protein thiols in cell extracts were alkylated with IAM followed by disulfide reduction and labeling with BODIPY FL C1-IA. NaOCl-sensitive proteins with increased redox-ratios in NaOCl-treated cells are red-labeled and the identified S-mycothiolated proteins are marked with (*). The oxidized proteins were identified by MALDI-TOF-TOF MS/MS and are listed with their ratios of reversible thiol-oxidations versus protein amounts ratios in Supplementary Table S4. IAM, iodoacetamide; LC, liquid chromatography. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

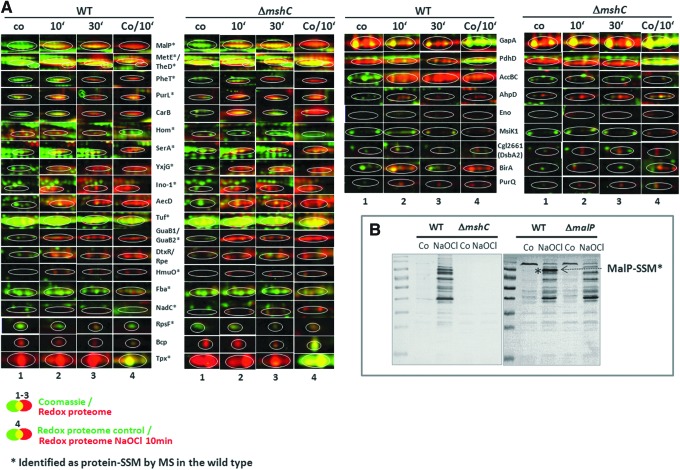

FIG. 3.

Close-ups of NaOCl-sensitive proteins identified in the thiol-redox proteomes of C. glutamicum wild type (WT) and the mshC mutant (A) and monitoring protein S-mycothiolation by MSH Western blot analysis (B). (A) Examples for reversibly oxidized proteins in the redox proteomes of the wild type (WT) and the mshC mutant are shown after NaOCl treatment. Among these NaOCl-sensitive proteins, 16 proteins are labelled with (*) that have been identified as S-mycothiolated in the wild type using LC-MS/MS analysis (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S5, Supplementary Fig. S5). Overlay images represent the redox proteome (red) compared to the Coomassie-stained protein amount image (green) at control conditions (co) and 10 and 30 min after NaOCl exposure (1–3). Column 4 represents the overlay of the redox proteomes of control cells (green) versus the redox proteome after 10 min of NaOCl stress (red). The identified proteins and their fluorescence/protein quantity ratios are listed in Supplementary Table S4 and the complete redox proteomes of the wild type and the mshC mutant are given in Supplementary Figures S3–S4. (B) Nonreducing MSH-specific Western blot analysis indicates widespread S-mycothiolation in C. glutamicum wild type. The IAM-alkylated protein extracts of the wild type, mshC and malP mutants were harvested before (co) and 15 min after 180 μM NaOCl stress and subjected to nonreducing MSH-specific Western blot analysis. LC, liquid chromatography; MSH, mycothiol. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

Treatment of C. glutamicum with 180 μM NaOCl stress resulted in strongly enhanced reversible thiol-oxidation of 30 NaOCl-sensitive proteins (Figs. 2 and 3; Supplementary Table S4). The search for conserved Cys residues using the CDD database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi) revealed that many of these proteins harbor nucleophilic Cys residues essential for catalysis, substrate or metal ion binding. These proteins are involved in the biosynthesis of carbohydrates, amino acids, cofactors, nucleotides, iron utilization, and protein translation. We were interested if the identified NaOCl-sensitive proteins are oxidized to S-mycothiolated proteins and monitored MSH-mixed protein disulfides using nonreducing MSH-specific Western blot analysis. The results showed enhanced protein S-mycothiolation specifically after NaOCl stress that was absent in the mshC mutant (Fig. 3B). However, the comparison of the redox proteomes between the wild type and the mshC mutant after NaOCl stress (Fig. 3A) revealed only little differences suggesting alternative S-thiolation in the absence of MSH. Notable was only the strong oxidation of the acetyl CoA carboxylase AccBC in the wild type by NaOCl stress that was missing in the mshC mutant due to lower protein amounts. In conclusion, the redox proteome and MSH Western blot results indicate that NaOCl stress causes strongly increased reversible thiol-oxidations, including protein S-mycothiolations in C. glutamicum wild-type cells.

Shotgun-LC-MS/MS identifies 25 proteins with S-mycothiolations in NaOCl-treated cells

Proteins that form MSH mixed disulfides after NaOCl stress were identified using LTQ-Orbitrap liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis. The specific S-mycothiolated Cys peptides were identified by searching the LC-MS/MS results for the 484 Da mass shift of MSH at Cys residues. We further observed that the precursor ions have lost myo-inositol during MS/MS fragmentation. These neutral loss precursor ions with a mass loss 180 Da were used as diagnostic abundant peaks for verification of S-mycothiolated peptides (Supplementary Fig. S5). In control cells, we identified two peroxidases, the Tpx S-mycothiolated at the active site Cys60 and the resolving Cys94 and the glutathione peroxidase (Gpx) S-mycothiolated at the active site Cys36. Interestingly, the spectral counts (quantitative value) of these Cys-SSM peptides of Tpx and Gpx increased strongly in NaOCl-treated cells. In addition, the Prx Bcp was identified with an Cys89-SS-Cys94 intramolecular disulfide peptide and the dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase Lpd was oxidized to the conserved Cys42-SS-Cys47 disulfide in control cells (Supplementary Fig. S6I, J).

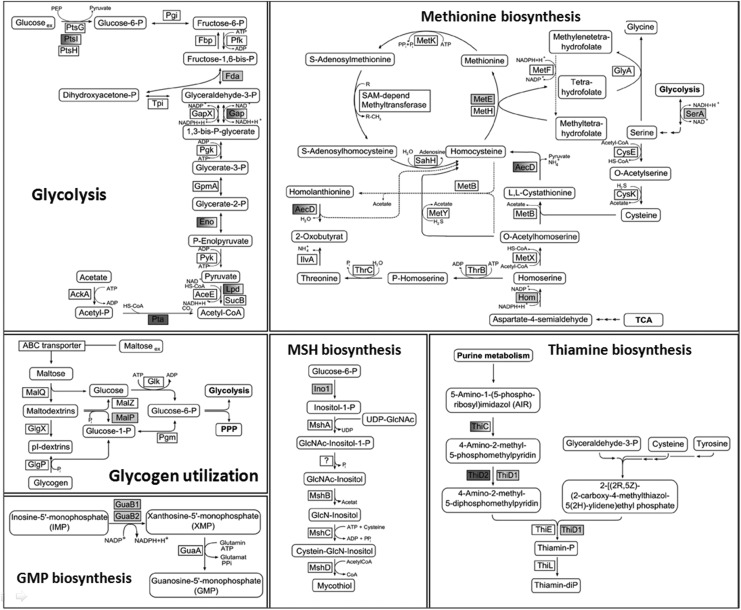

In NaOCl-treated cells, we identified 25 S-mycothiolated proteins in C. glutamicum with characteristic myo-inositol-loss precursor ions in their fragment ion spectra (Table 1; Supplementary Tables S5, Supplementary Fig. S5). These 25 S-mycothiolated proteins include 16 proteins identified also in the redox proteome as NaOCl-sensitive proteins, including Tuf, GuaB1, GuaB2, SerA, and MetE as conserved targets for S-thiolations across Gram-positive bacteria (7). The metabolic pathways, including the functions of the main S-mycothiolated proteins are shown in Figure 4. The S-mycothiolated proteins are involved in the metabolism of carbohydrates, for example, glycolysis (Fba, Pta, XylB), glycogen and maltodextrin degradation (MalP); amino acid biosynthesis pathways for serine, Cys, methionine (MetE, SerA, Hom); nucleotide and thiamine cofactor biosynthesis (GuaB1, GuaB, PurL, NadC, ThiD1 und ThiD2); redox and antioxidant functions for peroxide detoxification (Tpx, Gpx), methionine sulfoxide reduction (MsrA), heme degradation for iron mobilization (HmuO), and protein translation, such as ribosomal proteins (RpsF, RpsC, RpsM, RplM) and translation elongation factors (Tuf). The S-mycothiolated proteins MetE and MalP represent also very abundant proteins with strongly increased oxidation ratios after NaOCl stress in the redox proteome. The comparison of the S-mycothiolation pattern between wild type and malP mutant cells by nonreducing MSH-Western blots confirmed that MalP is one of the most strongly S-mycothiolated proteins in NaOCl-treated cells (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, also the first enzyme of the MSH biosynthesis pathways, the myo-Inositol-1-phosphate synthase (Ino-1 or Cg3323) was S-mycothiolated at Cys79 suggesting perhaps regulation of MSH biosynthesis under NaOCl stress.

Table 1.

Identifications of Proteins with S-Mycothiolations in the Corynebacterium glutamicum Wild Type and with S-Cysteinylations in the mshC Mutant Using LC-MS/MSa

| Cg-no | Protein | Function | Conservation and function of Cys with -SSM or -SSCys | Peptide-SSM or -SSCys*sequence | m/z precursor | Peptide MW | Charge | ΔPPM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolism of carbohydrates and amino acids | ||||||||

| Cg1479 | MalPb | Maltodextrin phosphorylase | Cys180 not cons. | (R)ASNQLVVC180(+484)FDDm(+16)K(T) | 985.4077 | 1968.8008 | 2 | 0.21 |

| (R)ASNQLVVC180(+119)FDDMK(T) | 530.2316 | 1587.6731 | 2 | −0.13 | ||||

| Cg1290 | MetEb,c | Methionine synthase | Cys713 Zn-bind. active site | (R)QLWVNPDC713(+484)GLK(T) | 878.8929 | 1755.7713 | 2 | 0.91 |

| (R)QLWVNPDC713(+119)GLK(T) | 464.5530 | 1390.6373 | 2 | −0.20 | ||||

| Cg1337 | Homb | Homoserine dehydrogenase | Cys239 not cons. | (R)VTADDVYC239(+484)EGISNISAADIEAAQQAGHTIK(L) | 1192.2073 | 3573.6000 | 3 | 0.63 |

| Cg3323 | Ino-1b | Myo-inositol-1-phosphate synthase | Cys79 not cons. | (K)VGIDLADATEASQNC79(+484)TIK(I) | 1167.0222 | 2332.0299 | 2 | −0.06 |

| (K)VGIDLADATEASQNC79(+119)TIK(I) | 656.6396 | 1966.8969 | 2 | −0.47 | ||||

| Cg3068 | Fbab | Fructose-bisphosphatealdolase | Cys332 not cons. | (R)IIESC332(+484)QDLK(S) | 766.8385 | 1531.6624 | 2 | −0.71 |

| Cg1451 | SerAb | Phosphoglyceratedehydrogenase | Cys266 not cons. | (R)GAGFDVYSTEPC266(+119)TDSPLFK(L) | 718.3111 | 2151.9115 | 2 | −0.79 |

| Cg3048 | Pta | Phosphate acetyltransferase | Cys367 not cons. | (R)RLNPELC367(+484)VDGPLQFDAAVDPGVAR(K) | 1012.8146 | 3035.4219 | 3 | −0.01 |

| Cg0147 | XylB | Sugar (pentulose and hexulose) kinase | Cys338 not cons. | (R)GVLAGLNC338(+484)ATTR(E) | 830.3814 | 1658.7483 | 2 | −0.58 |

| Metabolism of coenzymes and nucleotides | ||||||||

| Cg2964 | GuaB1b,c | Inosine-5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase | Cys302 forms Thioimidate, active site | (K)VGVGPGAmC302(+484)TTR(M) | 824.8462 | 1647.6778 | 2 | −0.80 |

| Cg0699 | GuaB2b,c | Inosine-5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase | Cys317 forms Thioimidate, active site | (K)VGIGPGSIC317(+484)TTR(V) | 822.8771 | 1643.7397 | 2 | 0.78 |

| Cg1215 | NadCb | Nicotinate-nucleotidepyrophosphorylase | Cys114 not cons. | (R)TSGIATLTSC114(+484)YVAEVK(G) | 1063.9893 | 2125.9640 | 2 | −0.36 |

| (R)TSGIATLTSC114(+119)YVAEVK(G) | 587.9507 | 1760.8302 | 3 | −1.33 | ||||

| Cg2862 | PurLb | Phosphoribosylformylglycinamidine synthase 2 | Cys716 not cons. | (K)LGC716(+484)TNDSAVIAVK(G) | 887.9076 | 1773.8006 | 2 | −0.39 |

| (K)LGC716(+119)TNDSAVIAVK(G) | 470.5635 | 1408.6687 | 2 | −0.34 | ||||

| Cg1654 | TheDb | Thiamine biosynthesisprotein | Cys451 active site, HMP substrate binding | (R)VNTTNSHGTGC451(+484)SLSASLATK(I) | 811.6971 | 2432.0694 | 2 | 0.45 |

| Cg3409 | ThiD2 | Hydroxymethylpyrimidine kinase | Cys111 not cons. | (K)HVVLDPVLIC111(+119)K(G) | 452.2452 | 1353.7139 | 2 | −0.87 |

| Antioxidant enzymes involved in the ROS response | ||||||||

| Cg1236 | Tpxb,d | Thiol peroxidase | Cys60 peroxidatic | (K)LVLNIFPSVDTGVC60(+484)ATSVR(K) | 1238.1064 | 2474.1983 | 2 | 2.51 |

| Cys94 resolving | (R)FC94(+484)SAEGIENVTPVSAFR(S) | 1156.0127 | 2310.0108 | 2 | 3.34 | |||

| Cg2867 | Gpxd | Glutathione (Mycothiol) peroxidase | Cys36 peroxidatic | (K)C36(+484)GLTPQYEGLQK(L) | 910.9011 | 1819.7877 | 2 | 1.02 |

| Cg2445 | HmuOb | Heme oxygenase | Cys165 not cons. | (R)EYGVSEEALSFYC165(+484)FEDLGK(L) | 1335.5519 | 2669.0892 | 2 | −1.25 |

| Cg3236 | MsrA | Peptide methioninesulfoxide reductase | Cys91cons. | (R)EVC91(+484)SGR(T) | 567.7182 | 1133.4218 | 2 | 0.19 |

| Translation factors and ribosomal proteins | ||||||||

| Cg0601 | RpsC | 30S ribosomal protein S3 | Cys153cons. | (K)VVC153(+484)SGR(L) | 552.7297 | 1103.4448 | 2 | −2.38 |

| Cg3308 | RpsFb | 30S ribosomal protein S6 | Cys67cons. | (K)C67(+484)ESATVLELDR(V) | 860.3685 | 1718.7225 | 2 | −0.13 |

| Cg0673 | RplM | 50S ribosomal protein L13 | Cys50 not cons. | (K)GKPLYAPNVDC50(+484)GDHVIVINADK(V) | 706.3352 | 2821.3117 | 4 | −1.28 |

| Cg0652 | RpsM | 30S ribosomal protein S13 | Cys86 not cons. | (R)KIEIGC86(+484)YQGIR(H) | 882.4106 | 1762.8066 | 2 | −3.01 |

| (R)KIEIGC86(+119)YQGIR(H) | 424.2026 | 1269.5859 | 2 | 0.89 | ||||

| Cg0587 | Tuf b,c | Elongation factor Tu | Cys277cons. | (K)LLDSAEAGDNC277(+484)GLLLR(G) | 1072.4940 | 2142.9735 | 2 | 3.34 |

| Cg1575 | PheTb | Phenylalanyl-tRNAsynthetase beta subunit | Cys89 in tRNA binding domain | (R)HC89(+484)HVNVGDANGTGELQSIVcGAR(N) | 960.0820 | 2877.2243 | 2 | −3.00 |

| Unknown function proteins | ||||||||

| Cgl1858 | WA5_1783 | Uncharacterized protein (WA5_1783) | Cys322 not cons. | (R)QVFC322(+484)LSSSGR(E) | 784.3330 | 1566.6515 | 2 | −1.70 |

Cytoplasmic protein extracts of Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC13032 wild type and the isogenic mshC mutant were harvested at 15 min after NaOCl stress in urea-IAM-buffer, tryptic in-gel-digested and the peptides were analyzed using a LTQ Orbitrap-Velos™ mass spectrometer as described in the Methods section. 25 Proteins with S-mycothiolations were identified by the additional mass of 484 Da at Cys residues and with the diagnostic neutral myo-inositol loss precursor ions that appeared as abundant ions in the MS/MS spectra of each mycothiolated peptide. Peptides with S-cysteinylations were identified with a mass difference of 119 Da at Cys residues. The table includes the protein names, Cg-accession numbers and protein functions as derived from the UniprotKB database (www.uniprot.org) and information about conservation of the mycothiolated Cys residues and Cys functions as revealed by the Conserved Domain Database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi). The table also includes the m/z of the precursor ions, the neutral molecular mass (MW) of the mycothiolated peptides, peptide charges and mass deviations (Δppm). The complete collision-induced diffraction (CID) MS/MS spectra of all S-thiolated peptides, the b and y fragment ion series, the SEQUEST Xcorr and SEQUEST ΔCn scores, and further peptide information are given in Supplementary Figures S5 and S6, and in Supplementary Table S5.

16 proteins have been identified as NaOCl-sensitive proteins in the Thiol-redox proteome (Figs. 2 and 3) with increased redox/protein ratios after NaOCl stress in this study. The redox/protein amount ratios are given in Supplementary Table S5.

The S-mycothiolated proteins MetE, GuaB and Tuf are also conserved targets for S-bacillithiolation in Bacillus or Staphylococcus species according to our previous study.

The S-mycothiolated peroxiredoxins Tpx and Gpx were identified in untreated and NaOCl-treated cells. All other S-mycothiolated proteins were only identified in NaOCl-exposed cells.

Cys, cysteine; IAM, iodoacetamide; LC-MS/MS, liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry; LTQ, linear trap quadrupole; MW, molecular weight; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

FIG. 4.

Metabolic pathways for glycolysis, biosynthesis of methionine, thiamine, GMP, MSH, and glycogen metabolism that include the identified S-mycothiolated metabolic enzymes. The enzymatic metabolic pathways were derived from the genome sequence of C. glutamicum or from previous publications (37) with the identified S-mycothiolated or reversibly oxidized proteins labeled with colors (S-mycothiolated proteins are dark gray; reversibly oxidized proteins are white-gray shadowed; both reversibly oxidized and S-mycothiolated proteins are light gray). The selected S-mycothiolated metabolic enzymes include MetE, SerA, Hom (Met biosynthesis); Fba, Pta (glycolysis); MalP (glycogen utilization); Ino-1 (MSH biosynthesis); ThiD1, ThiD2 (thiamine biosynthesis); GuaB1, GuaB2 (GMP biosynthesis). Further proteins with Cys-SSM sites are involved in translation (Tuf, PheT, RpsC, RpsF, RpsM, RplM) and antioxidant functions (Tpx, Gpx, MsrA) that are not shown here. Cys, cysteine; GMP, guanosine 5′-phosphate.

We were interested if proteins are S-thiolated by alternative redox buffers, such as ergothioneine (EGT) or Cys in C. glutamicum in the mshC mutant. In previous studies, we identified few proteins that are S-cysteinylated in the absence of BSH in B. subtilis, but the bshA mutant was more sensitive to NaOCl stress indicating that S-cysteinylation cannot fully compensate for S-bacillithiolation (6, 7). In Mycobacterium smegmatis, the histidine-derived thiol EGT has been suggested to compensate for the loss of MSH in mshA mutants (56). However, we were unable to detect proteins that form mixed disulfides with EGT in the mshC mutant. Instead, we identified eight S-cysteinylated proteins in the mshC mutant, which overlapped with only six proteins detected as S-mycothiolated in the wild type (MalP, MetE, Ino-1, PurL, NadC, and RpsM) (Table 1; Supplementary Table S5, Supplementary Fig. S6). The S-cysteinylated Cys-peptides identified in the mshC mutant were identical with the S-mycothiolated Cys-peptides of the wild type. However, compared to S-mycothiolated peptides the number of spectra (spectral counts) was significantly lower for S-cysteinylated petides and even for 19 S-mycothiolated proteins of the wild type no S-cysteinylated peptides were detected in the mshC mutant (Table 1; Supplementary Table S5B). These results indicate that Cys can be used for alternative S-thiolations in the absence of MSH, but S-cysteinylation cannot fully compensate for S-mycothiolation.

The roles of mycothiol, σH and MalP in protection against disulfide stress

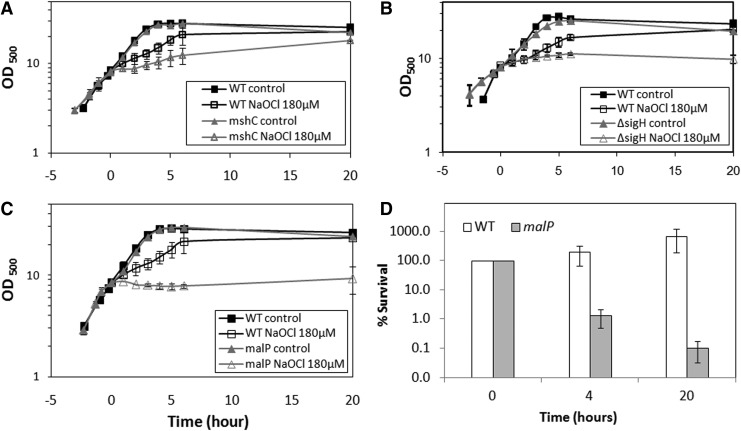

Next, we analyzed tpx, gpx, malP, mshC, and sigH mutants for their sensitivity to NaOCl stress in growth phenotype assays. Previously, the sigH and mshC mutants were shown to have decreased oxidative stress resistance in C. glutamicum (27, 35). In our growth phenotype assays, the mshC and sigH mutants are also very sensitive to NaOCl stress confirming previous results (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Mutants lacking MSH, σH and MalP are sensitive to NaOCl stress in growth assays. Growth phenotype assays of C. glutamicum wild type (WT) in comparison to the ΔmshC (A), ΔsigH (B) and ΔmalP (C) mutant strains that were treated with 180 μM NaOCl at an OD500 of 8 and growth was monitored. The survival assay of the ΔmalP mutant (D) after 180 μM NaOCl stress indicates a stronger killing effect of NaOCl in the mutant. OD500, optical density at 500 nm.

Growth phenotype assays further revealed an increased sensitivity of the malP mutant to NaOCl-stress indicating that S-mycothiolation of MalP confers protection against NaOCl stress (Fig. 5). The sensitivity of the malP mutant to NaOCl stress is caused by an increased killing effect of NaOCl stress as determined in survival assays. No NaOCl-sensitive growth phenotypes were detected for tpx and gpx mutants (data not shown). In conclusion, the σH/RshA disulfide stress system, MSH and MalP confer protection against NaOCl stress in C. glutamicum.

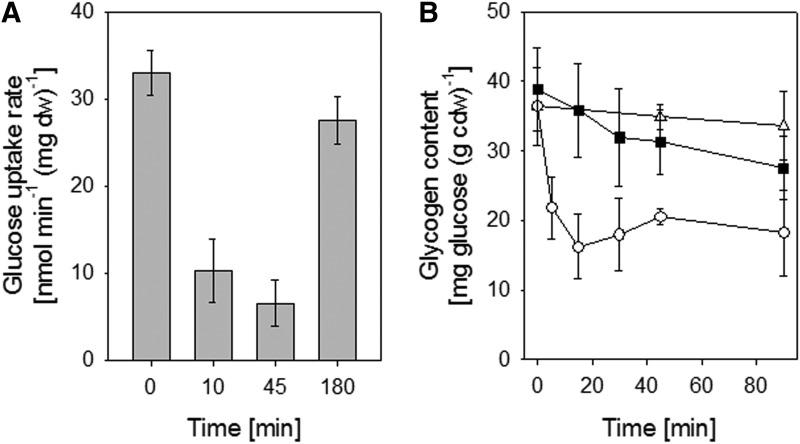

NaOCl stress leads to reduced glycogen degradation which could involve S-mycothiolation of MalP in vivo

In C. glutamicum, glycogen transiently accumulates during the exponential growth. Glycogen is degraded by MalP either slowly before the onset of the stationary growth phase or rapidly after osmostress when glucose uptake is reduced (52). It could be possible that S-mycothiolation of MalP prevents glycogen degradation to save the energy source under oxidative stress. To test an effect of S-mycothiolation of MalP on glycogen degradation in vivo, the glycogen content and glucose uptake rates (GURs) were determined after NaOCl stress. The GUR decreased about threefold 10 min after addition of NaOCl (Fig. 6A). For comparison, osmostress caused by NaCl leads to a twofold decrease of the GUR to 15.6±0.7 nmol/min/mg dw (52). The glycogen content was quickly decreased about twofold within 15 min after osmostress (Fig. 6B). However, the glycogen level of NaOCl-treated cells was only slightly reduced within 45 min of stress exposure. Since the glycogen content remains stable in NaOCl-treated cells, despite the drastically reduced glucose uptake, glycogen degradation could be inhibited by S-mycothiolation of MalP. Future studies are underway to determine the effect of S-mycothiolation on MalP activity in vitro.

FIG. 6.

Effects of NaOCl stress on the uptake of [14C]-labelled glucose (A) and intracellular glycogen content in C. glutamicum wild type (B). (A) The glucose uptake rates were determined after NaOCl stress as in previous studies (34). (B) The intracellular glycogen content was measured in untreated C. glutamicum wild type cells (Δ) and in cells treated with NaOCl (▪) or NaCl (○) stress. The time point 0 indicates the time of NaOCl or NaCl addition. Glycogen contents and glucose uptake rates were determined in triplicates from 3 biological replicate experiments.

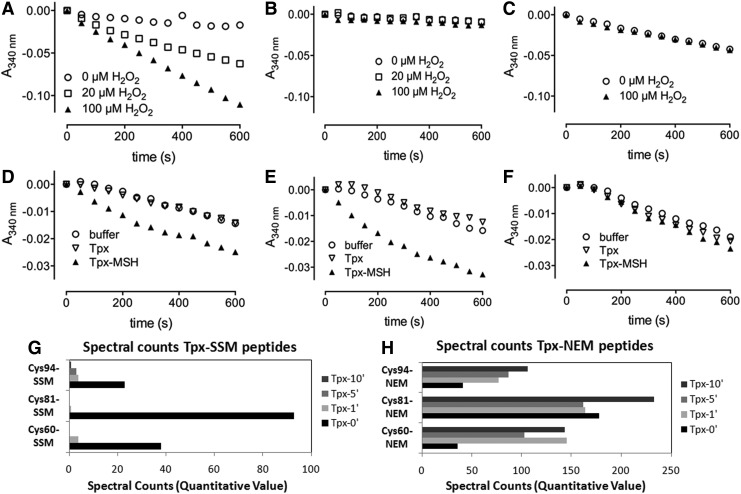

S-mycothiolation of Tpx in vitro abolishes its peroxidase activity which can be restored by the Mrx1/MSH/Mtr electron pathway

Next, we were interested to see whether the identified S-mycothiolated proteins are substrates for Mrx1. However, redox proteome comparison between the wild type and mrx1 mutants did not show a difference in the oxidation ratios of NaOCl-sensitive S-mycothiolated proteins (data not shown). Thus, we tested if S-mycothiolation affects the peroxidase activity of Tpx in vitro and if Mrx1 is able to reactivate Tpx. Tpx was expressed and purified from E. coli and the peroxidase activity of Tpx was analyzed in a coupled enzyme assay composed of Trx, TrxR, and NADPH. Purified Tpx has peroxidase activity when coupled to the Trx electron pathway, which is abolished when Tpx is omitted in this reaction (Fig. 7A, B). To test the effect of S-mycothiolation on the peroxidase activity, reduced Tpx was preincubated with reduced MSH before the addition of 1 mM hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). LC-MS/MS analysis revealed strong S-mycothiolation of all three Cys residues of Tpx, the peroxidatic Cys60, the resolving Cys94 and also the nonconserved Cys81 (Fig. 7, Supplementary Table S6). S-mycothiolation of Cys81 in vitro (but not in vivo) might be due to the much higher MSH amount applied in the in vitro reaction for purified Tpx.

FIG. 7.

Purified Tpx is active as peroxidase, inactivated by S-mycothiolation and can be reactivated by Mrx1 in vitro. (A) Progress curves for the consumption of NADPH are shown. The electron transfer pathway of Tpx with Trx, TrxR and NADPH was reconstructed with 20 μM (□) or 100 μM (▴)H2O2 as substrate for Tpx. A control sample (○) without H2O2was included. (B) An identical sample but with Tpx omitted showed no peroxidase activity. (C)The electron transfer pathway was reconstructed for S-mycothiolated Tpx showing no peroxidase activity. (D–F) The Mrx1 electron transfer pathway composed of Mrx1, MSH, Mtr and NADPH was reconstructed and reduced (▿) or S-mycothiolated (▴) Tpx was added as substrate. A control sample without Tpx (○) was included. In (D) 50 μM of reduced (▿) or S-mycothiolated (▴) Tpx was used and in (E) 75 μM of reduced (▿) or S-mycothiolated (▴) Tpx was used. (F) Mrx1 was omitted in the above pathways using 50 μM reduced (▿) or S-mycothiolated (▴) Tpx. In the absence of Mrx1, no electron transfer was observed. (G, H) Mass spectrometry revealed complete reduction of Tpx-SSM by Mrx1. The Spectral counts for the S-mycothiolated (G) and NEM-alkylated (H) Cys60-, Cys81- and Cys94-peptides of Tpx are calculated using the Scaffold software after different times of Mrx1 reduction (see Supplementary Tables S6A–C). H2O2, hydrogen peroxide; Mrx1, mycoredoxin1; NEM, N-ethylmaleimide; Trx, thioredoxin; TrxR, thioredoxin reductase.

The S-mycothiolation of Tpx most likely protects the active site from overoxidation to sulfinic and sulfonic acids during NaOCl stress, and might change its peroxidase activity. To test this, S-mycothiolated Tpx was used in this Trx/TrxR-coupled assay and no peroxidase activity was measured confirming that S-mycothiolation of the active site Cys60 inhibits the peroxidase activity (Fig. 7C) (48). To reactivate S-mycothiolated Tpx, we reconstructed the Mrx1/MSH/Mtr electron transfer pathway in vitro with S-mycothiolated Tpx as substrate. Control samples without Tpx or with nonmycothiolated Tpx were included in the assay. Only the sample with 50 μM Tpx-SSM showed consumption of NADPH and the rate of NADPH consumption increased when 75 μM Tpx-SSM was applied in this assay (Fig. 7D–F). No reduction of Tpx-SSM was observed when Mrx1 was omitted, indicating that the high MSH concentration (400 μM) is not sufficient to reduce Tpx-SSM without Mrx1. MS confirmed that the S-mycothiolated Cys60, Cys81, and Cys94 peptides are completely reduced within 5–10 min by Mrx1 (Fig. 7G, H, Supplementary Tables S6A, B). During Tpx-SSM reduction, Mrx1 gets S-mycothiolated at its active site Cys12 as transient Mrx1-SSM intermediate that was also detected by MS (Supplementary Table S6D). However, most Mrx1 protein was oxidized to the Cys12-SS-Cys15 intramolecular disulfide during Tpx-SSM reduction (Supplementary Table S6E).

Discussion

Mycothiol is the major LMW thiol in Actinomycetes and functions in detoxification of oxidants, electrophiles, toxins and several antibiotics (13, 39). In C. glutamicum, MSH plays very broad and essential roles in the detoxification of alkylating agents, toxins (methylglyoxal), oxidants (H2O2, diamide), antibiotics, glyphosate, ethanol, and toxic heavy metals (Zn, Co, Mn, Cr) (35). MSH is also an essential cofactor for the maleylpuruvate isomerase in the degradation of aromatic compounds, such as gentisate and 3-hydroxybenzoate and required also for detoxification of naphthalene and resorcinol (14, 35). Mutants in the MSH biosynthesis pathways were unable to grow in the presence of gentisate and 3-hydroxybenzoate, which indicates that MSH cannot be replaced by Cys as thiol-cofactor. In addition, MSH is required for conjugation of arsenate to a MSH-S-conjugate that is detoxified by two MSH-dependent arsenate reductases ArsC1 and ArsC2 in C. glutamicum (43).

In this article, we present for the first time evidence that MSH also functions in widespread protein S-mycothiolation as important thiol-protection mechanism under hypochlorite stress in C. glutamicum. In addition, we provide evidence that S-mycothiolation inhibits the peroxidase activity of Tpx in vitro which can be restored by Mrx1. Protein S-thiolation was induced in our previous study in B. subtilis by NaOCl stress, which causes a disulfide stress response and induction of the Spx, PerR and OhrR-regulons in the transcriptome (6). Here we confirmed that NaOCl stress elicits a disulfide stress response also in C. glutamicum that is controlled by the σH/RshA regulatory system (3). In addition, similar thiol-based redox regulators respond to NaOCl stress in both bacteria, belonging to the MarR/DUF24-family that control quinone oxidoreductases or to the ArsR-family regulating metal ion or arsenate efflux systems (6). The results that NaOCl stress causes a common disulfide stress response in bacteria are in agreement with the chemistry of NaOCl. Hypochlorite is defined as reactive chlorine species that leads to chlorination of thiol groups to form sulfenyl chloride (Cys-SCl) as unstable intermediate (20, 21). Cys-SCl reacts further with proximal thiols to form disulfides or is overoxidized to Cys sulfonic acid. Thus, S-mycothiolation is particularly important under NaOCl stress to prevent lethal overoxidation of Cys residues.

Using shotgun-LC-MS/MS analysis, we identified 25 cytoplasmic proteins that are S-mycothiolated under NaOCl stress conditions in the wild type and 16 of these are also major NaOCl-sensitive proteins in the thiol-redox proteome. In contrast, only 6 of these S-mycothiolated proteins were identified as S-cysteinylated in the absence of MSH with significantly lower spectral counts (Supplementary Table S5B). This indicates that S-cysteinylation can only partly compensate for alternative S-thiolations in the mshC mutant. However, due to the instability of S-thiolation modifications we cannot exclude that other redox buffers, like CoASH or EGT are also involved in S-thiolations in the absence of MSH. However, phenotype analyses of the mshC mutant support clearly that MSH is important for protection under NaOCl stress. The number of S-mycothiolated proteins is higher in C. glutamicum compared to S-bacillithiolated proteins identified in Bacillus or Staphylococcus in our previous work (7). This may be related to the higher MSH amounts present in Actinomycetes compared to BSH in Firmicutes (38). The proteins identified in the S-mycothiolome are functionally very similar to the identified S-bacillithiolated proteins in Firmicutes and S-glutathionylated proteins identified in eukaryotes (7, 33). Except for the thiol peroxidases Tpx and Gpx, all S-mycothiolated proteins were exclusively identified under NaOCl stress conditions, not in untreated cells, which confirms our previous results in Firmicutes bacteria. Thus, S-mycothiolation functions as redox switch and protects redox-sensitive thiols against overoxidation mainly under oxidative stress conditions.

The S-mycothiolated proteins were identified within the metabolic pathways for methionine biosynthesis (MetE, SerA, Hom), glycolysis (Fba, Pta, PckA), glycogen utilization (MalP), nucleotide biosynthesis (GuaB1, GuaB2, PurL, NadC), MSH biosynthesis (Ino1) and thiamine biosynthesis (ThiD1, ThiD2). Further S-mycothiolated proteins function in protein translation (Tuf, PheT, RpsC, RpsF, RpsM, RplM) or have antioxidant functions, such as the peroxidases Tpx and Gpx. In our previous study, we identified 8 conserved S-bacillithiolated proteins in B. subtilis and other Firmicutes bacteria, including the methionine synthase MetE, the inosine 5′-phosphate (IMP) dehydrogenase GuaB, the translation elongation factor Tuf, the inorganic pyrophosphatase PpaC, the phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase SerA, the chorismate mutase AroA, the ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase YumC and the putative bacilliredoxin YphP (6, 7). Interestingly, five of these conserved S-bacillithiolated proteins are also abundantly S-mycothiolated proteins in C. glutamicum, including MetE, GuaB1, GuaB2, Tuf and SerA. Thus, we hypothesize that these proteins are probably conserved targets for S-thiolations across bacteria. GuaB and MetE possess also conserved active site Cys residues, including the active site Zn center of MetE (Cys713 in Cg-MetE) or the thioimidate intermediate-forming active site in GuaB (Cys302 in Cg-GuaB1 and Cys317 in Cg-GuaB2). This active site of GuaB is buried in the GuaB structure from Vibrio cholerae (PDB code 4FEZ) (Supplementary Fig. S7). S-glutathionylation of GuaB has been also reported in human T-lymphocytes and endothelial cells (18, 32). It is further interesting that different enzymes of the thiamine biosynthesis pathway are S-thiolated in Firmicutes and C. glutamicum. For example, ThiG and ThiM were S-bacillithiolated in Bacillus and Staphylococcus (7), whereas the multifunctional ThiD1 protein with thiamine phosphate synthase and hydroxymethylpyrimidine (HMP) kinase domains was S-mycothiolated in C. glutamicum at Cys451 that is the conserved HMP substrate binding site.

MetE has been first shown as target for S-glutathionylation in E. coli where it is modified at the nonconserved Cys645 located at the entrance to the active site (22). The methionine synthase MetE is the major S-bacillithiolated protein in Bacillus species (6, 7) and its S-thiolation occurs in its active site Zn center at Cys730 and also at the nonconserved Cys719 in B. subtilis. This leads to MetE inactivation and Met auxotrophy in NaOCl-treated cells. Here we confirmed that MetE is also a major target for S-mycothiolation in C. glutamicum and is oxidized at the conserved active site Cys713. This Zn-binding active site Cys is buried in the MetE structures of Thermotoga maritima and Streptococcus mutans (PDB code 2NQ5) (Supplementary Fig. S7), but the elastic and flexible nature of this catalytic Zn center has been demonstrated (28). However, in contrast to E. coli and B. subtilis, NaOCl stress did not cause methionine starvation since growth was not resumed by addition of Met to the growth medium after 30 and 60 min of NaOCl treatment (Supplementary Fig. S1B). Thus, the growth defect after NaOCl stress could be caused by multiple amino acid auxotrophies or by a general translation defect caused by S-mycothiolation of translation elongation factors and ribosomal proteins. Similar translation proteins have also been detected as reversibly oxidized in the redox proteome of E.coli after NaOCl stress (31), and as S-glutathionylated in oxidatively stressed human endothelial and yeast cells (18, 33, 54). The inhibition of protein synthesis during the time of oxidant removal is perhaps one of the conserved consequences of protein S-thiolation as verified in yeast cells (54).

Besides the identification of many conserved S-thiolated proteins across Firmicutes and Actinobacteria, there are also unique S-thiolated proteins in C. glutamicum. For example, the myo-inositol-1 phosphate synthase Ino-1, the first enzyme of the MSH biosynthesis pathway was S-mycothiolated at Cys79 suggesting that MSH biosynthesis itself might be feed-back redox-controlled by oxidative stress. Interestingly, the Ino-1 homolog of M. tuberculosis was identified as pupylated at K73, which determines its degradation by the proteasome (16), but K73 is not conserved in C. glutamicum Ino-1. It will be interesting to analyze the activity of S-mycothiolated Ino-1 and a possible cross-talk with the Pup proteasome in C. glutamicum in future studies. The main target for S-mycothiolation was the maltodextrin phosphorylase MalP in C. glutamicum that is involved in glycogen and maltodextrin utilization in C. glutamicum (53). MalP is the major reversibly oxidized protein in the thiol redox proteome of C. glutamicum and S-mycothiolated at the nonconserved Cys180, which is the only surface-exposed Cys residue in the MalP crystal structure of Corynebacterium callunae (PDB code 2C4M). In addition, a malP mutant was very sensitive to NaOCl stress suggesting that S-mycothiolation of MalP confers resistance to oxidative stress in C. glutamicum. C. glutamicum has the capability to accumulate transiently glycogen as energy and carbon source during the exponential growth when grown on glucose. Glycogen is degraded during the stationary phase or during osmostress by the glucan phosphorylase GlgP, the debranching enzyme GlgX that produces maltodextrins and the maltodextrin phosphorylase MalP (Fig. 4) (53). Thus, S-mycothiolation of MalP could protect and inhibit the enzyme and prevent glycogen degradation to save their energy source under oxidative stress. Indeed, the glycogen content decreased only slightly in NaOCl-treated cells despite the reduced GUR. This inhibition of glycogen degradation could be caused by a loss of MalP activity due to S-mycothiolation (Fig. 6). Further studies are underway to characterize the effect of S-mycothiolation on MalP activity. We further identified several glycolytic enzymes as targets for S-thiolation (e.g., Fba) or reversible thiol-oxidation (e.g., GapA, Eno) in C. glutamicum that were also reversibly inactivated by S-thiolation in yeast cells (54). It is proposed that the inhibition of the glycolytic flux by S-thiolation redirects glucose into the pentose phosphate pathway for NADPH regeneration to provide the reducing power for the Trx and Mrx1 systems (54). The inhibition of glycolytic enzymes by S-thiolation could be also a consequence of the reduced GUR under NaOCl stress.

As most interesting proteins, we identified the peroxidases Tpx and Gpx as S-mycothiolated at their active sites. Tpx and Gpx have been classified as atypical 2-Cys Prxs with a conserved peroxidatic active site Cys (CP) and a resolving Cys (CR). Atypical Prxs react with peroxides to a transient CP-SOH intermediate that forms an intramolecular disulfide with CR in the same subunit that is reduced by the Trx pathway during recycling (36, 47). Since MSH-deficient mutants of C. glutamicum and M. smegmatis showed peroxide-sensitive phenotypes, the existence of MSH-dependent peroxidases was suggested earlier (13, 35). It is possible that Gpx might be the MSH-dependent peroxidase that utilizes MSH as electron donor for peroxide detoxification resulting in MSSM generation that could be recycled by Mtr. For M. tuberculosis Tpx (Tpx-Mtb) the catalytic cycle and structure has been resolved (PDB code 1XVQ)(17, 48). Tpx was S-mycothiolated at Cys60 and Cys94 in vivo that both are solvent exposed in the Tpx-Mtb structure in contrast to Cys81 that is more buried and not conserved (Supplementary Fig. S7). Tpx-Mtb shares 56.6% sequence identity to C. glutamicum Tpx (Tpx-Cg) and the Cys60-Cys94 intramolecular disulfide was confirmed here using MS (Supplementary Table S6C). Tpx-Cg showed also NADPH-linked peroxidase activity and reduced H2O2 in a Trx/TrxR-coupled assay. For E. coli Tpx, it was shown that the CP-SOH was sensitive to overoxidation (2), which explains the protection of the Cys60 active site against overoxidation by S-mycothiolation in our study. We could show that S-mycothiolation of CP and CR inhibits the peroxidase activity which can be restored after reduction by the Mrx1/MSH/Mtr electron pathway. Thus, S-mycothiolation controls Tpx activity and protects CP against overoxidation. S-glutathionylated Prxs have been observed as reaction intermediates in the catalytic mechanism of peroxidase activity of 2-Cys Prx from Schistosoma mansoni, poplar Prx, and human Prx-I (5, 46). S-glutathionylation of Prx-I induced a structural change that leads to dissociation from oligomers to dimers with a loss of chaperone activity and an increased peroxidase activity of the active dimer (5, 44, 46). For 1-Cys D-Prx, it is been shown that S-glutathionylation induced the dissociation of noncovalent homodimers to monomers that are reduced by the Grx/GSH system followed by dimerization and reactivation of the peroxidase activity (42). Also Tpx is active as homodimer and it will be exciting to unravel the structural changes of Tpx by S-mycothiolation that perhaps also regulates the quaternary structure by dimer to monomer dissociation.

Experimental Procedures

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and primers are listed in Supplementary Tables S7 and S8. For DNA manipulation and plasmid isolation, E. coli was cultivated in Luria Bertani (LB) medium at 37°C. C. glutamicum ATCC 13032 wild type and sigH, mshC, malP, tpx and gpx mutant strains were grown in CGC minimal salt medium containing 1% glucose as carbon source at vigorous agitation at 30°C (12). When appropriate, nalidixic acid (50 μg/ml for C. glutamicum) or kanamycin (20 μg/ml for C. glutamicum and 50 μg/ml for E. coli) were added to the media. Sodium hypochlorite (15% stock solution) and H2O2 were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. For NaOCl stress experiments, C. glutamicum cells were grown in CGC minimal medium to an OD500 of 8.0 and exposed to 180 μM NaOCl that was freshly diluted in distilled water. The survival of the malP mutant was determined after different times of NaOCl stress by plating serial dilutions on LB plates and determining colony forming units (cfu) after 2 days. The cfu of the untreated culture was set as 100% and three replicate experiments were performed.

Construction of defined deletions in the C. glutamicum chromosome

Gibson assembly was applied to construct pK18mobsacB derivatives to perform allelic exchange of the gpx and tpx genes in the chromosome of C. glutamicum ATCC 13032 (50). The primers used to construct the pK18mobsacB derivatives are listed in Supplementary Table S8, that includes the gpx and tpx genes with internal deletions (Δgpx [480 bp] and Δtpx [447 bp]). The pK18mobsacB derivatives were cloned in E. coli JM109 (Supplementary Table S7). The pDN2 plasmid containing the ΔsigH deletion was constructed previously (3) and transformed into C. glutamicum ATCC 13032. The gene replacement in the chromosome of C. glutamicum ATCC 13032 resulted in the ΔsigH, Δgpx, and Δtpx deletion mutants that were confirmed by PCR using the primers in Supplementary Table S8.

RNA isolation and DNA microarray hybridization

For RNA isolation, C. glutamicum ATCC 13032 cells were harvested before and 10 and 30 min after exposure to NaOCl stress from three replicate experiments and disrupted with a Precellys 24 homogenizer (Bertin Technologies). Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kit and treated with DNase-I as described (23). The hybridization of whole-genome oligonucleotide microarrays was performed using 15 μg of total RNA that was used for cDNA synthesis as described previously (49). The normalization and evaluation of the hybridization data was done with the software package EMMA 2 (9) using a signal intensity (a-value) cut-off of ≥7.0, a signal intensity ratio (m-value) cut-off of±1 (technical variance) for hierarchical clustering and±1 (significance threshold) for the single analysis. Genes with at least twofold expression changes and p-values<0.05 were considered as significantly changed genes.

Hierarchical clustering analysis

Clustering of gene expression profiles was performed using GENESIS (55). The transcriptome data sets included log2-fold expression changes of all genes with at least twofold expression changes (p-values<0.05) at 7.5 min after 2 mM diamide stress (Busche and Kalinowski, unpublished data), 10 and 30 min after 180 μM NaOCl, respectively.

Thiol redox proteomics and MALDI-TOF-TOF MS/MS

The thiol redox proteome analysis was performed as described (6). Cells were harvested at control and NaOCl stress conditions, sonicated, alkylated in 8 M urea/1% chaps/100 mM IAM, and acetone precipitated. The pellet was resolved in urea/chaps buffer without IAM and 200 μg of the protein extract was reduced with 10 mM TCEP and labelled with BODIPY FL C1-IA [N-(4,4-difluoro-5,7-dimethyl-4-bora-3a,4a-diaza-s-indacene-3-yl)-methyl)-iodoacetamide] (Invitrogen). The fluorescence-labeled protein extract was separated using two-dimensional (2D) polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), scanned for BODIPY fluorescence and stained with Coomassie as described (6). Quantitative image analysis was performed with the DECODON Delta 2D software (www.decodon.com). The oxidation ratios were calculated as fluorescence/protein amount ratios and listed in Supplementary Table S4. Tryptic digestion of proteins, peptide-spotting, and MALDI-TOF-TOF measurement was performed using a Proteome-Analyzer 5800 (Applied Biosystems) as described (6).

LTQ-Orbitrap Velos MS

IAM-alkylated cell extracts were separated by 15% nonreducing sodium dodecylsulfate (SDS)-PAGE and tryptic in-gel digested as described (6). Tryptic peptides were subjected to a reversed phase column chromatography and MS and MS/MS data were acquired with the LTQ-Orbitrap-Velos mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with a nanoelectrospray ion source as described (6). Post-translational thiol-modifications of proteins were identified by searching all MS/MS spectra in “dta” format against a C. glutamicum ATCC13032 target-decoy protein sequence database extracted from UniprotKB release 12.7 (UniProt Consortium, Nucleic acids research 2007, 35, D193-197) using Sorcerer™-SEQUEST® (Sequest v. 2.7 rev. 11, Thermo Electron, including Scaffold 4.0; Proteome Software, Inc.). The Sequest search was carried out with the following parameters: parent ion mass tolerance 10 ppm, fragment ion mass tolerance 1.00 Da. Two tryptic miscleavages were allowed. Methionine oxidation (+15.994915 Da), Cys carbamidomethylation (+57.021464 Da), S-cysteinylations (+119.004099 Da for C3H7NO2S), S-mycothiolations (+484.13627 Da for MSH) and S-ergothionylations (+227.07284 for EGT) were set as variable post-translational modifications in the Sequest search. Sequest identifications required ΔCn scores of >0.10 and XCorr scores of >2.2, 3.3 and 3.75 for doubly, triply and quadruply charged peptides, respectively. Neutral loss precursor ions characteristic for the loss of inositol (−180 Da) served for verification of the S-mycothiolated peptides.

Nonreducing MSH specific Western blot analysis

Twenty-five microgram IAM-alkylated protein extracts were used for nonreducing 15% SDS-PAGE and MSH-specific Western blots as described (7). Polyclonal MSH antiserum was kindly obtained from Mamta Rawat and used at 1:500 dilution.

Analyses of the glycogen content and [14C]-glucose uptake studies

Analyses of the intracellular glycogen content were performed enzymatically as described (51). [14C]-glucose uptake studies were performed as described (34). After different times of stress exposure, the glucose uptake reaction was then started by addition 50 μM [14C]-glucose (specific activity 250 μCi μmol−1; Moravek Biochemicals). At given time intervals (15, 30, 45, 60, and 90 s), 200 μl samples were filtered through glass fibre filters (Typ F; Millipore) and washed twice with 2.5 ml of 100 mM LiCl. Radioactivity of the samples was determined using scintillation fluid (Rotiszinth; Roth) and a scintillation counter (LS 6500; Beckmann).

Cloning and purification of Tpx, Trx, TrxR, and Mrx1

Recombinant Trx, TrxR, and Mrx1 were cloned and purified as described by Ordóñez et al. (43). Tpx was cloned into plasmid pET28a (using primers tpx_pETfor and tpx_pETrev and the restriction sites: NcoI, XhoI). The resulting Tpx-pET28 vector, containing Tpx with a N-terminal HIS6-tag and a PreScission protease cleavage site (GE Healtcare) was transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3). The transformed cells were grown overnight at 37°C in LB medium with 50 μg/ml kanamycin. The cultures were 100-fold diluted into LB medium with 50 μg/ml kanamycin, induced with 1 mM IPTG at an OD600 of 0.7 and grown overnight at 30°C. Cells were harvested and resuspended in 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 5 mM imidazole, 1 M NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mg/ml 4-(2-aminoethyl) benzene sulfonyl fluoride hydrochloride and 1 μg/ml leupeptin to an OD600 of 200. After cell crack disruption, 50 μg/ml DNase I and 20 mM MgCl2 were added to cell lysate, left for 30 min at 4°C before centrifugation. The supernatant was loaded on a Ni2+-Sepharose (GE Healthcare) immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) column equilibrated with 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 5 mM imidazole, 1 M NaCl, 1 mM DTT, and eluted with a linear gradient to 1 M imidazole in the same buffer. The eluted fractions were analyzed on SDS-PAGE (15% Tris-glycine) and the fractions with Tpx were pooled and further purified on a Superdex75PG (16/90) SEC column equilibrated in 20 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8.0), 250 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT.

In vitro S-mycothiolation of Tpx

Tpx was incubated with a 6 M excess of reduced MSH before the addition of 1 mM H2O2. After an incubation of 5 min, the sample was loaded on an IMAC column and MSH and H2O2 were removed by a washing step with 50 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl. S-mycothiolated Tpx was eluted in the same buffer containing 300 mM imidazole.

Coupled Trx/TrxR and Mrx1/MSH/Mtr electron transfer assays

The Trx/TrxR and Mrx1/MSH/Mtr coupled enzyme assays described by Van Laer et al. were modified to include Tpx (57). Briefly, Tpx was reduced by 10 mM DTT for 15 min at room temperature and the excess of DTT was removed by size exclusion chromatography in 50 mM Hepes, pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl. The Tpx/Trx/TrxR electron transfer pathway was reconstructed by incubating 500 μM NADPH, 3 μM TrxR, and 1500 nM Trx with 500 nM Tpx at 37°C in the assay buffer containing 50 mM Hepes pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl. Increasing concentrations of H2O2 (20–100 μM) were added as substrate to the reaction mixture. The oxidation of NADPH due to H2O2 reduction was monitored as a decrease in the absorption at 340 nm in function of time. The Mrx1/MSH/Mtr assay contained 500 μM NADPH, 5 μM Mtr, 400 μM MSH, and 2 μM Mrx1. Mycothiolated Tpx (50 or 75 μM final concentration) was added and the absorption at 340 nm was monitored in function of time.

Purification and reduction of MSH

MSH was purified as described in Ordóñez et al. (43). Oxidized MSH was incubated with 25 mM TCEP and incubated for 20 min at room temperature. The sample was loaded on an anion exchange chromatography (Isolute PE-AX column) and MSH was eluted in water. As a quality control, a 1D proton NMR spectra in D2O was recorded and compared to the spectra obtained by Lee and Rosazza (30).

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations Used

- BSH

bacillithiol

- Cys

cysteine

- EGT

ergothioneine

- GMP

guanosine 5′-phosphate

- Gpx

glutathione peroxidase

- Grx

glutaredoxin

- GSH

glutathione

- GSSG

oxidized glutathione disulfide

- GST

glutathione S-transferase

- GUR

glucose uptake rate

- HED

ß-hydroxyethyl disulfide

- HMP

hydroxymethylpyrimidine

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- IAM

iodoacetamide

- IMP

inosine 5′-phosphate

- LB

Luria Bertani

- LC

liquid chromatography

- LMW

low molecular weight

- LTQ

linear trap quadrupole

- Met

methionine

- Mrx1

mycoredoxin1

- MS

mass spectrometry

- MS/MS

tandem mass spectrometry

- MSH

mycothiol

- MSSM

mycothione or mycothiol disulfide

- Mtr

mycothiol disulfide reductase

- MW

molecular weight

- NEM

N-ethylmaleimide

- OD500

optical density at 500 nm

- PAGE

polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- protein-SSM

MSH protein mixed disulfide

- Prx

peroxiredoxin

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SDS

sodium dodecylsulfate

- TCEP

Tris-(2-carboxyethyl)-phosphine

- Tpx

thiol peroxidase

- Trx

thioredoxin

- TrxR

thioredoxin reductase

Acknowledgments

We thank Dirk Albrecht for the MALDI-TOF-MS analysis; Dana Clausen and Eva Glees for excellent technical assistance and Eva Schulte-Bernd for performing the microarray hybridizations. We wish to thank Mamta Rawat for providing polyclonal MSH antibodies and Johanna Milse for the mshC mutant. G.M.S. and L.C. thank Reinhard Krämer (Cologne) for continuous support. The support of the BMBF (grant 0315589F “FlexFit”) is gratefully acknowledged. This work was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (AN746/3-1) to H.A.

K.V.L. and J.M. thanks the agentschap voor innovatie door Wetenschap en technologie (IWT), Vlaams Instituut voor Biotechnologie (VIB), and the HOA project of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB) for their support. J.M. is group leader for Redox Biology of the VIB. We acknowledge the BMBS COST action BM1203 (EU-ROS).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Antelmann H. and Helmann JD. Thiol-based redox switches and gene regulation. Antioxid Redox Signal 14: 1049–1063, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker LM. and Poole LB. Catalytic mechanism of thiol peroxidase from Escherichia coli. Sulfenic acid formation and overoxidation of essential CYS61. J Biol Chem 278: 9203–9211, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Busche T, Silar R, Picmanova M, Patek M, and Kalinowski J. Transcriptional regulation of the operon encoding stress-responsive ECF sigma factor SigH and its anti-sigma factor RshA, and control of its regulatory network in Corynebacterium glutamicum. BMC Genomics 13: 445, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bussmann M, Baumgart M, and Bott M. RosR (Cg1324), a hydrogen peroxide-sensitive MarR-type transcriptional regulator of Corynebacterium glutamicum. J Biol Chem 285: 29305–29318, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chae HZ, Oubrahim H, Park JW, Rhee SG, and Chock PB. Protein glutathionylation in the regulation of peroxiredoxins: a family of thiol-specific peroxidases that function as antioxidants, molecular chaperones, and signal modulators. Antioxid Redox Signal 16: 506–523, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chi BK, Gronau K, Mader U, Hessling B, Becher D, and Antelmann H. S-bacillithiolation protects against hypochlorite stress in Bacillus subtilis as revealed by transcriptomics and redox proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics 10: M111 009506, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chi BK, Roberts AA, Huyen TT, Basell K, Becher D, Albrecht D, Hamilton CJ, and Antelmann H. S-bacillithiolation protects conserved and essential proteins against hypochlorite stress in firmicutes bacteria. Antioxid Redox Signal 18: 1273–1295, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dalle-Donne I, Rossi R, Colombo G, Giustarini D, and Milzani A. Protein S-glutathionylation: a regulatory device from bacteria to humans. Trends Biochem Sci 34: 85–96, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dondrup M, Albaum SP, Griebel T, Henckel K, Junemann S, Kahlke T, Kleindt CK, Kuster H, Linke B, Mertens D, Mittard-Runte V, Neuweger H, Runte KJ, Tauch A, Tille F, Puhler A, and Goesmann A. EMMA 2—a MAGE-compliant system for the collaborative analysis and integration of microarray data. BMC Bioinformatics 10: 50, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ehira S, Ogino H, Teramoto H, Inui M, and Yukawa H. Regulation of quinone oxidoreductase by the redox-sensing transcriptional regulator QorR in Corynebacterium glutamicum. J Biol Chem 284: 16736–16742, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ehira S, Teramoto H, Inui M, and Yukawa H. Regulation of Corynebacterium glutamicum heat shock response by the extracytoplasmic-function sigma factor SigH and transcriptional regulators HspR and HrcA. J Bacteriol 191: 2964–2972, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eikmanns BJ, Thum-Schmitz N, Eggeling L, Ludtke KU, and Sahm H. Nucleotide sequence, expression and transcriptional analysis of the Corynebacterium glutamicum gltA gene encoding citrate synthase. Microbiology 140(Pt 8): 1817–1828, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fahey RC. Glutathione analogs in prokaryotes. Biochim Biophys Acta 1830: 3182–3198, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feng J, Che Y, Milse J, Yin YJ, Liu L, Ruckert C, Shen XH, Qi SW, Kalinowski J, and Liu SJ. The gene ncgl2918 encodes a novel maleylpyruvate isomerase that needs mycothiol as cofactor and links mycothiol biosynthesis and gentisate assimilation in Corynebacterium glutamicum. J Biol Chem 281: 10778–10785, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernandes AP. and Holmgren A. Glutaredoxins: glutathione-dependent redox enzymes with functions far beyond a simple thioredoxin backup system. Antioxid Redox Signal 6: 63–74, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Festa RA, McAllister F, Pearce MJ, Mintseris J, Burns KE, Gygi SP, and Darwin KH. Prokaryotic ubiquitin-like protein (Pup) proteome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis [corrected]. PLoS One 5: e8589, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flohe L, Toppo S, Cozza G, and Ursini F. A comparison of thiol peroxidase mechanisms. Antioxid Redox Signal 15: 763–780, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fratelli M, Demol H, Puype M, Casagrande S, Eberini I, Salmona M, Bonetto V, Mengozzi M, Duffieux F, Miclet E, Bachi A, Vandekerckhove J, Gianazza E, and Ghezzi P. Identification by redox proteomics of glutathionylated proteins in oxidatively stressed human T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99: 3505–3510, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaballa A, Newton GL, Antelmann H, Parsonage D, Upton H, Rawat M, Claiborne A, Fahey RC, and Helmann JD. Biosynthesis and functions of bacillithiol, a major low-molecular-weight thiol in Bacilli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107: 6482–6486, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gray MJ, Wholey WY, and Jakob U. Bacterial responses to reactive chlorine species. Annu Rev Microbiol 2013[Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1146/annurev-micro-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hawkins CL, Pattison DI, and Davies MJ. Hypochlorite-induced oxidation of amino acids, peptides and proteins. Amino Acids 25: 259–274, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hondorp ER. and Matthews RG. Oxidative stress inactivates cobalamin-independent methionine synthase (MetE) in Escherichia coli. PLoS Biol 2: e336, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huser AT, Becker A, Brune I, Dondrup M, Kalinowski J, Plassmeier J, Puhler A, Wiegrabe I, and Tauch A. Development of a Corynebacterium glutamicum DNA microarray and validation by genome-wide expression profiling during growth with propionate as carbon source. J Biotechnol 106: 269–286, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kehr S, Jortzik E, Delahunty C, Yates JR, 3rd, Rahlfs S, and Becker K. Protein S-glutathionylation in malaria parasites. Antioxid Redox Signal 15: 2855–2865, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim JS. and Holmes RK. Characterization of OxyR as a negative transcriptional regulator that represses catalase production in Corynebacterium diphtheriae. PLoS One 7: e31709, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim MS, Dufour YS, Yoo JS, Cho YB, Park JH, Nam GB, Kim HM, Lee KL, Donohue TJ, and Roe JH. Conservation of thiol-oxidative stress responses regulated by SigR orthologues in actinomycetes. Mol Microbiol 85: 326–344, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim TH, Kim HJ, Park JS, Kim Y, Kim P, and Lee HS. Functional analysis of sigH expression in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 331: 1542–1547, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koutmos M, Pejchal R, Bomer TM, Matthews RG, Smith JL, and Ludwig ML. Metal active site elasticity linked to activation of homocysteine in methionine synthases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105: 3286–3291, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee JW, Soonsanga S, and Helmann JD. A complex thiolate switch regulates the Bacillus subtilis organic peroxide sensor OhrR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104: 8743–8748, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee S. and Rosazza JP. First total synthesis of mycothiol and mycothiol disulfide. Org Lett 6: 365–368, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leichert LI, Gehrke F, Gudiseva HV, Blackwell T, Ilbert M, Walker AK, Strahler JR, Andrews PC, and Jakob U. Quantifying changes in the thiol redox proteome upon oxidative stress in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105: 8197–8202, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lind C, Gerdes R, Hamnell Y, Schuppe-Koistinen I, von Lowenhielm HB, Holmgren A, and Cotgreave IA. Identification of S-glutathionylated cellular proteins during oxidative stress and constitutive metabolism by affinity purification and proteomic analysis. Arch Biochem Biophys 406: 229–240, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lindahl M, Mata-Cabana A, and Kieselbach T. The disulfide proteome and other reactive cysteine proteomes: analysis and functional significance. Antioxid Redox Signal 14: 2581–2642, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lindner SN, Petrov DP, Hagmann CT, Henrich A, Kramer R, Eikmanns BJ, Wendisch VF, and Seibold GM. Phosphotransferase system-mediated glucose uptake is repressed in phosphoglucoisomerase-deficient Corynebacterium glutamicum strains. Appl Environ Microbiol 79: 2588–2595, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu YB, Long MX, Yin YJ, Si MR, Zhang L, Lu ZQ, Wang Y, and Shen XH. Physiological roles of mycothiol in detoxification and tolerance to multiple poisonous chemicals in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Arch Microbiol, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mishra S. and Imlay J. Why do bacteria use so many enzymes to scavenge hydrogen peroxide? Arch Biochem Biophys 525: 145–160, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neuweger H, Persicke M, Albaum SP, Bekel T, Dondrup M, Huser AT, Winnebald J, Schneider J, Kalinowski J, and Goesmann A. Visualizing post genomics data-sets on customized pathway maps by ProMeTra-aeration-dependent gene expression and metabolism of Corynebacterium glutamicum as an example. BMC Syst Biol 3: 82, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Newton GL, Arnold K, Price MS, Sherrill C, Delcardayre SB, Aharonowitz Y, Cohen G, Davies J, Fahey RC, and Davis C. Distribution of thiols in microorganisms: mycothiol is a major thiol in most actinomycetes. J Bacteriol 178: 1990–1995, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Newton GL, Buchmeier N, and Fahey RC. Biosynthesis and functions of mycothiol, the unique protective thiol of Actinobacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 72: 471–494, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Newton GL, Fahey RC, and Rawat M. Detoxification of toxins by bacillithiol in Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiology 158: 1117–1126, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Newton GL, Rawat M, La Clair JJ, Jothivasan VK, Budiarto T, Hamilton CJ, Claiborne A, Helmann JD, and Fahey RC. Bacillithiol is an antioxidant thiol produced in Bacilli. Nat Chem Biol 5: 625–627, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Noguera-Mazon V, Lemoine J, Walker O, Rouhier N, Salvador A, Jacquot JP, Lancelin JM, and Krimm I. Glutathionylation induces the dissociation of 1-Cys D-peroxiredoxin non-covalent homodimer. J Biol Chem 281: 31736–31742, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ordóñez E, Van Belle K, Roos G, De Galan S, Letek M, Gil JA, Wyns L, Mateos LM, and Messens J. Arsenate reductase, mycothiol, and mycoredoxin concert thiol/disulfide exchange. J Biol Chem 284: 15107–15116, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Park JW, Mieyal JJ, Rhee SG, and Chock PB. Deglutathionylation of 2-Cys peroxiredoxin is specifically catalyzed by sulfiredoxin. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 23364–23374, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Park JH. and Roe JH. Mycothiol regulates and is regulated by a thiol-specific antisigma factor RsrA and sigma(R) in Streptomyces coelicolor. Mol Microbiol 68: 861–870, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Park JW, Piszczek G, Rhee SG, and Chock PB. Glutathionylation of peroxiredoxin I induces decamer to dimers dissociation with concomitant loss of chaperone activity. Biochemistry 50: 3204–3210, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Poole LB, Hall A, and Nelson KJ. Overview of peroxiredoxins in oxidant defense and redox regulation. Curr Protoc Toxicol Chapter 7: Unit7 9, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rho BS, Hung LW, Holton JM, Vigil D, Kim SI, Park MS, Terwilliger TC, and Pedelacq JD. Functional and structural characterization of a thiol peroxidase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Mol Biol 361: 850–863, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ruckert C, Milse J, Albersmeier A, Koch DJ, Puhler A, and Kalinowski J. The dual transcriptional regulator CysR in Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC 13032 controls a subset of genes of the McbR regulon in response to the availability of sulphide acceptor molecules. BMC Genomics 9: 483, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schafer A, Tauch A, Jager W, Kalinowski J, Thierbach G, and Puhler A. Small mobilizable multi-purpose cloning vectors derived from the Escherichia coli plasmids pK18 and pK19: selection of defined deletions in the chromosome of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Gene 145: 69–73, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Seibold G, Dempf S, Schreiner J, and Eikmanns BJ. Glycogen formation in Corynebacterium glutamicum and role of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase. Microbiology 153: 1275–1285, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Seibold GM. and Eikmanns BJ. The glgX gene product of Corynebacterium glutamicum is required for glycogen degradation and for fast adaptation to hyperosmotic stress. Microbiology 153: 2212–2220, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Seibold GM, Wurst M, and Eikmanns BJ. Roles of maltodextrin and glycogen phosphorylases in maltose utilization and glycogen metabolism in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Microbiology 155: 347–358, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]