Abstract

Tumors are complex masses containing not just neoplastic cells but also stromal cells, neovasculature, and a gamut of immune cells. In this issue, Bindea, et al, (2013) identify a surprising new ‘immune landscape’ associated with prolonged disease-free survival.

The amount of data that is available to every member of society with a high speed Internet connection has increased at such a rate that it boggles the mind. One recent estimate is that the amount of data coursing through the global Internet in 2013 will be over 500 billion giga-bytes of information. This represents an increase of 10-fold over the past 5 years alone. This ‘Big Data Revolution’ is likely to affect fields as diverse as weather forecasting and crime fighting, and the conduct of immunobiology is certainly no exception.

Bindea et al. (2013) have used this new-found ability to generate and to manipulate large amounts of data from varieties of sources to cast new light on the tumor microenvironment. In this issue of Immunity, Bindea, et al offer an extraordinarily high resolution view of the immune cells found within surgically-excised tumor masses.

It has long been appreciated that established tumors are complex masses that contain not only neoplastic cells but also non-transformed cellular elements such as stromal cells, the neovasculature, and a gamut of immune cells. Tumor masses have been compared to rogue organ systems that are comprised of collections of cells that compete with each other and with normal tissue in a Darwinian struggle for survival(Khong and Restifo, 2002). The complexity of these constantly evolving systems is apparent, and elucidating all of the cellular constituents – let alone their interactions with each other – is well out of reach of even the most sophisticated teams of pathologists.

Human tumors are triggered by a myriad of causes and evolve over periods measured in years and decades, and are not easily modeled in animals. Individual scientists pursuing reductionist approaches can provide informative narratives about particular cells and pathways and molecules, but a full and unbiased embrace of complexity in the human system provides much needed bird’s eye view of this ongoing research. The development of high-throughput techniques like whole genome analysis and multicolor immunohistochemistry and multi-parameter flow cytometry – along with the bioinformatics tools to analyze the resultant data – has put a high-resolution view of tumor complexity within reach.

Previous work from Galon’s group has elucidated the major importance of cytotoxic and memory T cells in determining disease-free survival in cohorts of patients (Galon et al., 2006; Pages et al., 2005). The authors have cogently argued that a patient’s ‘Immunoscore’ based on the quantification of specific patterns of immune activation in the tumor microenvironment can yield information that is highly associated with patient prognosis. Currently, patients with colorectal cancer are usually given prognoses based on a staging system established by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC). This system is called the TNM system (for tumors-nodes-metastases) because it employs measurements such as the degree of invasion of the intestinal wall, the amount of tumor involvement of nearby lymphatic structures, and the presence or absence of distant metastases to assign patients to stages, numbered I–IV. However, reports from the Galon group have used Cox multivariate analysis to claim that the predictive value of the ‘Immunoscore’ exceeds that of the TNM system currently in place(Mlecnik et al., 2011).

These data are consistent with a plethora of observations from other studies (Fridman et al., 2012) and in addition they fit with findings that clinically effective immunotherapies to date all depend on these endogenous T cells. Approaches to cancer immunotherapy that result in objective tumor regressions include the adoptive transfer of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (Restifo et al., 2012) as well as antibodies to immune ‘checkpoints’ CTLA4 and PD1-PDL1 (Topalian et al., 2012; van Elsas et al., 2001).

Here, Bindea et al. (2013) use systems biology approaches to quantify 28 different immune cell subpopulations (both innate and adaptive) cells in situ in human tumors. This approach relies on analysis of whole genome expression, which is backed up using PCR arrays and multicolored immunohistochemistry and even mouse models. The authors have previously identified the importance of cytotoxic and memory T cells, but what is substantially new in the present data set is the addition of key roles for T follicular helper (Tfh) and B cells identified using microarrays and immunohistochemistry, and this new data adds significantly to the alogorithms used to predict patient disease-free survival. These particular immune cells are identified and quantified using a set of signature genes specific for leukocytes subsets that were obtained using highly purified, flow-sorted cells.

The authors confirmed this data using highly sensitive quantitative PCR to further investigate the expression of 81 relatively cell-specific genes, most of them membrane receptors, to study 153 patients with colorectal cancer. Using this approach, the authors found that the genes identifying the ‘adaptive immune clusters,’ defined here as T, B and Tfh cells, were highly correlated with patient disease-free survival. Specifically, patients with elevations in MHC-II, B cell co stimulatory-related genes, T cell, and Tfh cell related genes had increased survival whereas there was no significant correlation with MHC-I and inflammation-related genes. Furthermore, the expression of markers for Tfh cells and B cells were correlated with each other in an unsupervised analysis. Importantly, the pattern changed over time. With the exception of Tfh cells, most T cell subpopulations marked by CD8, CD45RO, CD57 and FOXP3 ebbed with tumor progression. In contrast, the density of B cells increased with tumor stage, as did the innate immune cells such as neutrophils, mast cells, iDC, pDC and macrophages.

Underpinning the current conclusions was the finding that one chemokine in particular, CXCL13, and one cytokine, IL-21, were found to be critical and positively correlated with disease-free survival. Critics might complain that these conclusions are based on vignettes of large amounts of primary data, and still unresolved is the clear and rigorous delineation a ‘training set’ and a ‘test set.’ Despite these shortcomings, the authors deploy considerable bioinformatic and statistical know how in the form of their CluePedia and ClueGO software (Bindea, et al, 2013). More importantly for immunologists, they also show how the major components of their findings exist in plausible immune networks (Fig 1). In addition, the authors find that a tumor mechanism (chromosomal deletion of CXCL13) is associated with decrease CXCL13 production, and decreased densities of Tfh and B cells.

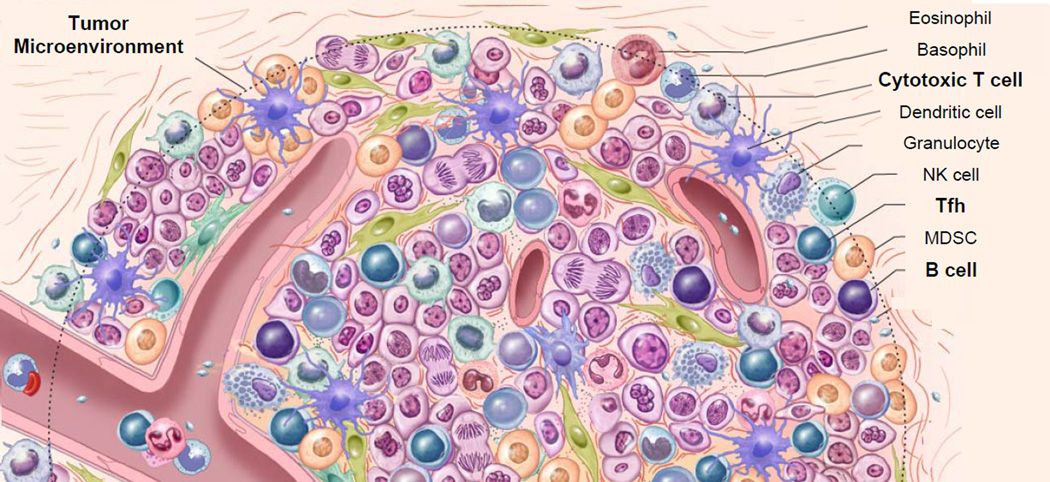

Figure.

Immune cells in tumor. Tumors masses are complex mixtures of cells that contain stromal cells, vasculature and a wide array of immune cells. Unsupervised correlation matrix of intra-tumor ‘immunome’ reveals that of the 28 cell types that were specifically analyzed, the strongest correlations with increased disease-free survival were with CTL, Tfh and B cells (shown in bold), which furthermore were correlated with each other.

Patients with more Th17 cells trended toward having a worse prognosis. It was perhaps striking that there was a notable lack of evidence in these new datasets for a major negative role of immune cell subsets that classically mediate immunosuppression. For example, T regulatory cells were not predictive in this dataset. Cells that might be designated as myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC) such as monocyte populations were not specifically looked at, although neutrophils, macrophages and dendritic cell subsets each of which might have components deemed to be MDSC, were notably absent as prognostic predictors. Thus, these negative cellular influences did not proclaim themselves as predictors of negative outcomes in these patient cohorts, a surprising finding given the wealth of data in animal models indicating the importance of cellular immunosuppression in the tumor microenvironment.

The authors assemble a large amount of information in an effort to visualize the “Immune Landscapes” that are associated with progression and recurrence of colorectal cancer in their patient cohorts. Changes in the immune landscape help us to understand the evolution of the immune response that the authors observe with tumor progression. Given these new findings, one might conclude that immunotherapies involving Tfh cell and IL-21 might be of great interest. Based on recent work from a diversity of research laboratories, these suggestions are intriguing.

Tfh cells are a CD4+ T cell subset that constitutively expresses CXCR5, a G protein-coupled seven transmembrane receptor for CXCL13 (the central chemokine identified in this analysis). Tfh cells might be involved in the formation of secondary lymphoid structures that can be visualized in some human tumor samples. Tfh cells also trigger the secretion of IL-21 a key component of the immune signature found here. In addition to helping to form follicular structures, IL-21 through its action via STAT3, might be critical in retaining tumor-stimulated CD8+ T cells in less-differentiated and more potent states (Hinrichs et al., 2008).

There seems little doubt that careful quantification of tumor infiltrating immune cells can help determine a patient’s prognosis in colorectal cancer, and this alone represents a major advance. It is still too early to know if this detailed information about the tumor immune microenvironment can be used to guide the treatment of patients with cancer. Nevertheless, ‘Big Data’ – carefully crunched using innovative software tools – may ultimately serve as a great illuminator of the biology of the anti-tumor response, spurring new and more effective cancer immunotherapies.

This is a commentary on article Bindea G, Mlecnik B, Tosolini M, Kirilovsky A, Waldner M, Obenauf AC, Angell H, Fredriksen T, Lafontaine L, Berger A, Bruneval P, Fridman WH, Becker C, Pagès F, Speicher MR, Trajanoski Z, Galon J.Spatiotemporal dynamics of intratumoral immune cells reveal the immune landscape in human cancer. Immunity. 2013;39(4):782-95.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bindea Cite, et al. Immunity, Present Issue. [Google Scholar]

- Fridman WH, Pages F, Sautes-Fridman C, Galon J. The immune contexture in human tumours: impact on clinical outcome. Nature reviews. Cancer. 2012;12:298–306. doi: 10.1038/nrc3245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galon J, Costes A, Sanchez-Cabo F, Kirilovsky A, Mlecnik B, Lagorce-Pages C, Tosolini M, Camus M, Berger A, Wind P, et al. Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science. 2006;313:1960–1964. doi: 10.1126/science.1129139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinrichs CS, Spolski R, Paulos CM, Gattinoni L, Kerstann KW, Palmer DC, Klebanoff CA, Rosenberg SA, Leonard WJ, Restifo NP. IL-2 and IL-21 confer opposing differentiation programs to CD8+ T cells for adoptive immunotherapy. Blood. 2008;111:5326–5333. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-113050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khong HT, Restifo NP. Natural selection of tumor variants in the generation of "tumor escape" phenotypes. Nature immunology. 2002;3:999–1005. doi: 10.1038/ni1102-999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pages F, Berger A, Camus M, Sanchez-Cabo F, Costes A, Molidor R, Mlecnik B, Kirilovsky A, Nilsson M, Damotte D, et al. Effector memory T cells, early metastasis, and survival in colorectal cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2005;353:2654–2666. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Restifo NP, Dudley ME, Rosenberg SA. Adoptive immunotherapy for cancer: harnessing the T cell response. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2012;12:269–281. doi: 10.1038/nri3191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, Gettinger SN, Smith DC, McDermott DF, Powderly JD, Carvajal RD, Sosman JA, Atkins MB, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;366:2443–2454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Elsas A, Sutmuller RP, Hurwitz AA, Ziskin J, Villasenor J, Medema JP, Overwijk WW, Restifo NP, Melief CJ, Offringa R, Allison JP. Elucidating the autoimmune and antitumor effector mechanisms of a treatment based on cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 blockade in combination with a B16 melanoma vaccine: comparison of prophylaxis and therapy. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2001;194:481–489. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.4.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]