Abstract

Red ginseng (RG, Panax ginseng) has been shown to possess various ginsenosides. These ginsenosides are widely used for treating cardiovascular diseases in Asian communities. The present study was designed to evaluate the cardioprotective potential of RG against isoproterenol (ISO)-induced myocardial infarction (MI), by assessing electrocardiographic, hemodynamic, and biochemical parameters. Male porcines were orally administered with RG (250 and 500 mg/kg) or with vehicle for 9 days, with concurrent intraperitoneal injections of ISO (20 mg/kg) on the 8th and 9th day. RG significantly attenuated ISO-induced cardiac dysfunctions as evidenced by improved ventricular hemodynamic functions and reduced ST segment and QRS complex intervals. Also, RG significantly ameliorated myocardial injury parameters such as antioxidants. Malonaldialdehyde formation was also inhibited by RG. Based on the results, it is concluded that RG possesses significant cardioprotective potential through the inhibition of oxidative stress and may serve as an adjunct in the treatment and prophylaxis of MI.

Key Words: : antioxidant, hemodynamic function, myocardial infarction, myocardial protection, red ginseng

Introduction

Myocardial infarction (MI) continues to be a health problem causing mortality and morbidity despite clinical care and public concern.1 It is well known that MI is a common symptom of myocardial ischemia, and occurs when cardiac injury surpasses a critical threshold, resulting in mortal cardiac damage.2 In MI, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are the primary components of oxidative damage of cardiomyocytes.3 Thus, much research has been devoted to studying the role of antioxidants in preventing MI.4,5

Catecholamines are responsible for cardiac necrosis,6 and oxidation of catecholamines is also known to result in the generation of toxic ROS.7 Therefore, it is likely that ROS may play a key role in catecholamine-induced toxicity by the peroxidation of cardiac cell membranes. Isoproterenol (ISO), a β-adrenergic agonist, is known to produce cardiac ischemia due to free radical production by autooxidation.8 ISO-induced cardiac ischemia results in increased cardiac enzymes and oxidative stress, abnormal electrocardiograph and cardiac functions.9 It was also reported that the pathophysiological and morphological abnormalities induced by ISO were comparable with cardiac ischemia in humans.10 Among the many mechanisms of cardiac ischemia induced by ISO, production of ROS by peroxidation of catecholamines has been shown to play a key role in inducing cardiac ischemia. Numerous previous studies have shown that antioxidants may inhibit the progression of cardiac ischemia.11,12 Accordingly, many natural antioxidants are recognized to have potential as herbal medicines for reducing the occurrence of cardiovascular diseases.13

Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer is widely used as a traditional herbal medicine and exhibits many functional activities such as antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-aging potencies.14 Commercially available P. ginseng is classified into two types. The first type has been subjected to steaming and drying, known as red ginseng (RG), and the second type, which has been subjected to air drying only, is known as white ginseng (WG). Yamabe et al. reported that the free radical scavenging activities in ginseng are increased by heating processes.15 Clinically, it is well known that RG offers more potent effects than WG, therefore, RG is used more often for treating cardiovascular diseases. Interestingly, RG has been shown to comprise structural transformations in the active properties, particularly in ginsenosides when steamed and dried from P. ginseng.16

The present study was designed to evaluate the effect of RG pretreatment on the ISO-induced myocardial damage in a porcine model. This study also attempted to clarify the mechanism for the efficacy of RG by studying the biochemical markers, antioxidant defense system, and echocardiogram (ECG) parameters.

Materials and Methods

Animals and RG extracts

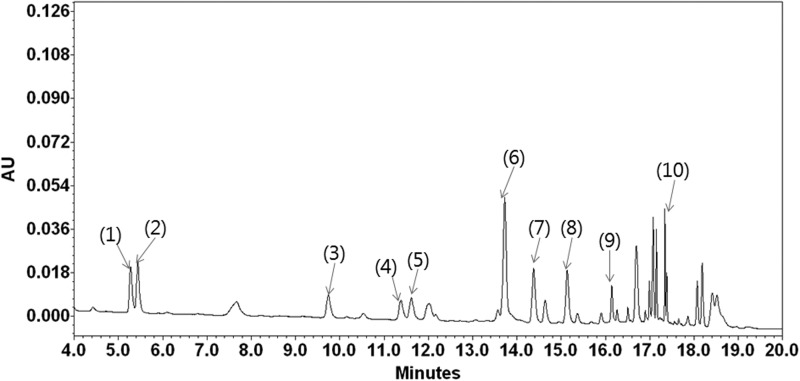

Male domestic Yorkshire Landrace porcines (n=25) ranging from 25 to 30 kg were obtained from Hanil Experiment Animal Breeding (Yeumsung, Korea). The porcines were housed at an ambient temperature of 25±2°C with alternating 12-h light–12-h dark cycles. Each porcine had free access to standard food and water ad libitum for 3 days for acclimatization. The experimental protocol was approved by the Chonbuk National University Ethics Committee for the use of experimental animals (approved number: CBU 2012-0049) and conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Efforts were made to minimize the numbers of animals used and to reduce their suffering. RG extract is made from 6-year-old Korean RG: 70% of the main root and 30% of secondary roots (dry matter 64%). RG was supplied by the Korea Ginseng Corporation (KGC, Seoul, Korea) and was extracted with 50% ethanol from Korean RG manufactured with 6-year-old P. ginseng C.A. Meyer. A voucher specimen (KGC No. 201-3-1081) of RG was deposited at the herbarium located at the KGC Central Research Institute (Daejeon, Republic of Korea). The contents of ginsenosides in RG, analyzed by the high-performace liquid chromatography/evaporative light scattering detector (HPLC-ELSD) method,17 were composed of ginsenoside Rg1, 2.01 mg/g; Re, 2.58 mg/g; Rf, 1.61 mg/g; Rh1, 0.95 mg/g; Rg2S, 1.35 mg/g; Rb1, 8.27 mg/g; Rc, 3.90 mg/g; Rb2, 3.22 mg/g; Rd, 1.09 mg/g; Rg3S, 1.04 mg/g; and other minor ginsenosides and components (Fig. 1). RG was dissolved in tap water to concentrations of 250 and 500 mg/kg.

FIG. 1.

High-performance liquid chromatogram of the red ginseng (RG). Peak identification: 1, ginsenoside-Rg1; 2, -Re; 3, -Rf; 4, -Rh1; 5, -Rg2s; 6, -Rb1; 7, -Rc; 8, -Rb2; 9, -Rd; 10, -Rg3s.

Induction of MI

It is known that intravenous administration of 10 mg/kg ISO induces severe cardiovascular side effects in the porcine.18 Soltysinska et al. reported that daily intraperitoneal injection of ISO (final dose of 1 mg/kg) for 3 months induced heart failure as evidenced by cardiac hypertrophy, basal systolic dysfunction, and reduced contractile reserve in guinea pigs.19 MI was also induced by subcutaneous injection of ISO below the skin at 20 and 85 mg/kg dosage for twice a day.20,21 In a pilot study, MI was induced by intraperitoneal administration of 10, 20, and 40 mg/kg of ISO into all groups of porcines twice at an interval of 24 h. From the preliminary results, an ISO dose of 20 mg/kg was selected since this dosage offered significant alterations in biochemical parameters, which to our knowledge has not been reported before. All animals were sacrificed 24 h after administration of the second injection of ISO.

Experimental protocols

The 25 porcines were equally divided into five groups (n=5, each group). The normal control group was administered saline for 9 days. In the RG control group, porcines were orally administered with a 500 mg/kg dose of RG once a day for 9 days as a sham control. In ISO control, porcines were administered with physiological saline for 9 days and injected with ISO (20 mg/kg, administered intraperitoneally twice at a 24-h interval) beginning on the 8th and 9th days. In the 250 and 500 mg/kg RG administered groups, porcines were administered with RG (250 and 500 mg/kg; gastric gavages, respectively) for 9 days; on the 8th and 9th days, two intraperitoneal injections with dose of 20 mg/kg of ISO at a 24-h interval were performed.

Electrocardiography and echocardiography

At the end of the above experiments, the animals were intraperitoneally anesthetized with 1 g/kg urethane, followed by ECG recordings. Briefly, at the end of the experimental period, needle electrodes were inserted under the skin of the porcines under anesthesia in lead II position. ECG recordings were made using a computerized MP30 data acquisition system (BIOPAC, Santa Barbara, CA), and changes in ECG pattern were considered. Elevation and decline of QRS complexes and ST segments in each group were calculated. The ECG study was performed within 20 min after anesthetic administration using the GE VingMed Vivid FiVe Ultrasound System (GE Healthcare, Brondby, Denmark) equipped with a 10 MHz pediatric probe. Cardiac left ventricle (LV) systolic pressure (LVSP) and LV developed pressure (+dP/dtmax and –dP/dtmin), fractional shortening (FS), and ejection fraction (EF) were continuously monitored using the 16-channel PowerLab system (AD Instruments, Oxford, United Kingdom). Left ventricle systolic function was assessed by calculating the LV endocardial FS and midwall FS.22 Each echocardiographic variable was determined in at least four separate LV images taken from the same heart. The mean values were used for statistical analysis.

Evaluation of myocardial enzymes

After ECG and echocardiography, porcines were sacrificed and the heart was excised for biochemical estimations. The heart tissues were stored at –80°C until ready for further analysis in each group. A 10% homogenate of heart was prepared in phosphate buffer saline (pH 7.4, 50 mM). Aliquots of tissue homogenate were cold centrifuged at 7000 g for 20 min and the supernatant was used for estimation of protein,23 superoxide dismutase (SOD),24 catalase (CAT),25 and glutathione peroxidase (GPx).26 The collected serum also was used for the estimation of cardiac marker enzymes lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and creatinine kinase-MB (CK-MB) using commercially available standard enzymatic kits (Span Diagnostics Pvt. Ltd., Surat, India). The malonaldialdehyde (MDA), indicative of lipid peroxidation formation, was assessed according to its absorbencies by spectrophotometry (specify the spectrophotometer used and wavelength).27 Tissue nitric oxide (NO) levels were correlated with nitrite determination from myocardial homogenates. The nitrite level was determined by using the diazotization method. It was measured spectrophotometrically at 545–555 nm wave length.28

Myeloperoxidase and cardiac troponin I assay

To quantify neutrophil infiltration, the activity of myeloperoxidase (MPO), an abundant enzyme found in neutrophils, was evaluated using a modified method.29 Briefly, myocardial tissue was homogenized in 50 mM K2HPO4 buffer (pH 6), containing 0.5% hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide, using a Polytron tissue homogenizer. After freeze thawing for three times, the samples were centrifuged at 11,000 g for 30 min at 40°C, and the resultant supernatants were assayed spectrophotometrically at 460 nm for MPO determination. MPO activity data are presented as U/mg of tissue. Troponin I (cTnI) activities, a sensitive and specific biomarker of cardiac injury,30 were measured with an ACS:180 automated chemiluminescence system using commercial kits supplied from Bayer Diagnostics (Cedex, France).31

Statistical analysis

The results are expressed as the mean±SD, whereby n=5 for all data. Statistically significant differences between groups at baseline and at the end of the study were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's post hoc test (SAS Institute, Inc. Cary, NC, USA). Differences with P<.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

RG inhibits the increase in cardiac enzymes

The porcine serum enzyme (CK-MB and LDH) levels are summarized in Table 1, which depicts the effects of RG on these marker enzymes. The activities of these enzymes increased significantly in ISO-treated porcine as compared with normal control (P<.01). Conversely, RG pretreatment in ISO-treated porcine significantly decreased the CK-MB and LDH activities (P<.01 for 250 and 500 mg/kg of CK-MB and LDH). The baseline, however, did not show any significant difference on the activities of CK-MB and LDH enzymes compared with each group. No significant difference was observed in porcines treated with RG alone when compared with the normal control group.

Table 1.

Effects of Red ginseng on the Activities of Lactate Dehydrogenase and Creatine Kinase from the Serum in Isoproterenol-Induced Myocardial Injury

| LDH (IU/L) | CK-MB (IU/L) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Baseline | End-ISO | Baseline | End-ISO |

| N/C | 196.45±13.87 | 194.37±9.97 | 65.84±5.15 | 63.87±6.89 |

| RG | 187.54±10.63a | 185.42±10.16a | 63.54±6.67a | 62.54±5.68a |

| ISO control | 189.13±12.46a | 426.54±19.86## | 67.42±5.46a | 173.54±9.46## |

| 250 mg/kg RG+ISO | 191.43±9.92a | 336.48±38.52** | 64.96±6.54a | 122.47±11.42** |

| 500 mg/kg RG+ISO | 185.63±11.48a | 293.75±31.59** | 66.47±5.76a | 98.84±10.28** |

Results are expressed as the mean±SD in each group (n=5, each group).

Not significantly different (P>.05) as compared with N/C.

Significantly different (P<.01) as compared with ##N/C or **ISO control.

LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; CK-MB, creatine kinase; ISO, isoproterenol; N/C, normal control; RG, red ginseng.

RG improves antioxidant activity and nitrite levels

The antioxidant enzyme activities of SOD, CAT, GSH-Px, and MDA are shown in Table 2. These enzyme activities were significantly decreased in the cardiac tissues of ISO-treated porcines as compared with normal control porcines. Moreover, ISO-treated porcines exhibited significant increases in MDA levels in cardiac tissues. The RG control group pretreated with RG (500 mg/kg) did not show any significant changes in enzyme activities of SOD, CAT, GPx, and MDA, indicating that RG per se does not exert any additional effects. The pretreatment of RG (500 mg/kg for 9 days) along with ISO injection on the 8th and 9th day showed significant increases in the SOD, CAT, and GPx levels (P<.05 for 250 mg/kg RG and P<.01 for 500 mg/kg RG). Furthermore, the pretreatment with RG (250 and 500 mg/kg) for 9 days before ISO injection significantly decreased the elevated MDA levels as compared with the ISO control group (*P<.05 and **P<.01). In addition, nitrite levels in the ISO control group were significantly lower than those in RG pretreatment (P<.05 for 250 mg/kg RG and P<.01 for 500 mg/kg RG). As shown in Table 2, the pretreatment with 500 mg/kg of RG is more effective than that seen with 250 mg/kg in normalization of nitrite levels as well as oxidative stress indicators. However, nitrite levels following 500 mg/kg RG pretreatment plus ISO injection were not different from the 250 mg/kg RG plus ISO injection.

Table 2.

Effects of Red Ginseng on the Activities of Antioxidant Parameters

| Group | SOD (U/mg protein) | CAT (U/mg protein) | GPx (U/mg protein) | MDA (nmol/mg protein) | Nitrite (mmol/g tissue) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N/C | 19.41±2.97 | 18.56±1.24 | 0.72±0.05 | 12.84±1.97 | 296.87±25.63 |

| RG | 18.73±2.82a | 17.96±1.38a | 0.74±0.06a | 13.01±1.75a | 339.42±32.54a |

| ISO control | 11.47±3.05## | 11.37±0.96## | 0.43±0.09## | 24.58±2.32## | 148.76±22.72## |

| 250 mg/kg RG+ISO | 18.82±4.24* | 13.76±1.88* | 0.57±0.07* | 19.12±2.38* | 225.63±47.49* |

| 500 mg/kg RG+ISO | 23.54±3.96** | 15.65±1.97** | 0.65±0.09** | 14.84±2.02** | 263.84±39.86** |

Results are expressed as the mean±SD in each group (n=5, each group).

Not significantly different (P>.05) as compared with N/C.

Significantly different (P<.01) as compared with N/C.

Significantly different as compared with ISO control (*P<.05, **P<.01).

SOD, superoxide dismutase; CAT, catalase; GPx, glutathione peroxidase; MDA, malondialdehyde.

RG normalizes ECG parameters and hemodynamic functions

Normal and RG control showed normal patterns of ECG, whereas ISO control showed a significant increase in the QRS complex (Fig. 2A) and ST segment intervals (Fig. 2B) as compared with the normal control indicative of cardiac infarction. Whereas pretreatment of RG (250 and 500 mg/kg) significantly decreased QRS complex intervals, ST segment intervals were also significantly decreased by the pretreatment of RG as compared with the ISO control group as shown in Figure 2A and B. Hemodynamic data such as LVSP, +dP/dtmax, −dP/dtmax, FS, and EF were determined in each group. The LVSP, +dP/dtmax, and −dP/dtmax values were significantly decreased as shown in Figure 2C–E. Similarly decreased values of FS and EF were also shown in ISO control as seen in Figure 3B and C. However, no difference in the hemodynamic data between normal and RG control groups was found. Our present study also revealed no difference in heart rates in each group (data not shown). Despite the absence of these LV structural remodeling such as LV dilatation and hypertrophy, hemodynamic functions decreased by ISO were significantly increased by pretreatment with RG. Whereas RG (250 and 500 mg/kg) improved the LVSP, +dP/dtmax, and −dP/dtmax (*P<.05 and **P<.01) (Fig. 2C–E). Both FS and EF were increased compared with ISO control (Fig. 3B, C). In comparison to normal control (normal control designated as 100%), the ISO control group had an average FS of 62.43±10.64%. The FS values were 79.67±7.84% for 250 mg/kg RG and 88.96±5.75% for 500 mg/kg RG, respectively, as seen in Figure 3B. The ISO control group had an average EF of 56.94±9.85%. However, as seen in Figure 3C, the EF values were 68.76±7.94% and 78.64±7.27% for 250 and 500 mg/kg RG, respectively. These hemodynamic data were significantly ameliorated compared with ISO controls. These results indicate that the pretreatment of RG at 250 and 500 mg/kg doses is effective for preserving the hemodynamic function.

FIG. 2.

The effect of RG on electrocardiographic evaluations: effects of RG on the QRS complex (A), ST-segment intervals (B), left ventricular systolic pressure (LVSP) (C), left ventricular contraction (+dP/dtmax) (D), and the maximal rate of change in left ventricular relaxation (–dP/dtmin) (E). ECG was recorded from limb leads II with a recorder speed of 50 ms/div in each group. Data are presented as mean±SD from total five porcines per group (*P<.05, **P<.05 vs. isoproterenol [ISO] control).

FIG. 3.

The effect of RG on echocardiographic evaluations. (A) 1: Echocardiography was performed on normal porcine hearts, showing the normal cardiac function such as fractional shortening (FS) and ejection fraction (EF). 2: Echocardiography was shown in porcine hearts pretreated with RG only for 7 days, also showing the normal cardiac function. 3: ISO control injected intraperitoneally twice at a 24-h interval exhibited worsening cardiac function such as FS and EF. 4 and 5: Echocardiography was performed after pretreatment with 250 or 500 mg/kg RG for 7 days before ISO injection twice at a 24-h interval, showing the recovery of FS and EF, respectively. Also, the effects of RG on the recovery of FS and EF were shown. (B, C) FS and EF as indices of cardiac function were shown with histogram by measurement of echocardiography. (D) Activity of cardiac troponin I in the heart tissue. Data are presented as mean±SD from total five porcines per group (*P<.05, **P<.01 vs. ISO control). N/C, normal control, RG, RG control; ISO, ISO control; 250 RG+ISO and 500 RG+ISO groups, pretreatment of 250 and 500 mg/kg RG for 7 days before ISO injection.

RG inhibits cardiac troponin I and MPO activity

The cTnI activity of normal and experimental groups are shown in Figure 3D. The cTnI levels from ISO control were significantly higher than in normal control groups. Significantly less biochemical damage was observed in the 250 and 500 mg/kg RG pretreatment group compared with the ISO control group. Moreover, the RG control group administered with only 500 mg/kg of RG did not show any significant change in the cTnI activity compared with normal control, indicating that RG per se does not exert any adverse effects. Furthermore, the neutrophil infiltration (Fig. 4A) ISO controls were significantly increased compared with normal and RG control groups (Fig. 4B). RG pretreatment led to a significant decrease in the myocardial MPO activity as compared with ISO control. Specifically, the normal control and RG control groups demonstrated MPO activities of 6.72±0.25 U/mg and 5.98±0.37 U/mg of tissue. For the ISO control, a significant increase of 17.65±1.35 U/mg of tissue was detected. RG pretreatment at 250 and 500 mg/kg for 7 days led to a significant decrease in the elevated MPO activity (13.84±1.54 U/mg of tissue for 250 mg/kg of RG and 11.76±1.03 U/mg of tissue for 500 mg/kg of RG). There were no significant differences in any measured biochemical parameters of MPO activity between normal and RG control (P>.05).

FIG. 4.

The effect of RG on neutrophil infiltration in the myocardium. (A) 1 and 2: Representative microscopic images of swine ventricles in N/C and RG control groups, respectively. 3, 4, and 5: Microscopic images in ISO control, 250 RG+ISO, and 500 RG+ISO groups stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Arrows indicate neutrophil infiltration (original magnification ×100). (B) A histogram expresses the measurements of myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity. Data are presented as mean±SD from total five porcines per group (*P<.05, **P<.01 vs. ISO control; scale bar: 100 μm).

Discussion and Conclusions

The cardiomyocyte defense system consists of antioxidant enzymes, which includes SOD, CAT, and GPx.32 Among these enzymes, SOD plays an important role in regulating mitochondrial ROS produced during oxidative reaction and protects cells against oxidative stress.32 CAT also plays a role in controlling ROS in myocytes by handling hydrogen peroxide, which is the product of SOD.33 In addition, a GPx, glutathione-dependent antioxidant enzyme, protects cellular membranes from oxidative stress.32 ISO might have exceeded the ability of free radical scavenging enzymes to remove the ROS, resulting in inactivation of free radical scavengers and cardiac injury.34 Previously, it was reported that ISO induced MI by lipid peroxidation that is related with ROS.35 Whereas it is well known that RG acts as an antioxidant.36 In addition, He et al., reported cardioprotective effects of ginseng saponin against oxidative stress damage and cardiomyocyte death.37 On this basis, the present study suggested that the decreased activities of SOD, CAT, and GPx by ISO were significantly increased by RG, indicating the potential of RG for inhibition of oxidative stress arising from impaired antioxidant enzymes. These results suggested that RG could bolster the antioxidative defense system against production of ROS. In addition, the treatment of RG decreased elevated MDA levels by ISO in the myocardium. The decrease of MDA levels might be due to the increased activities of SOD, CAT, and GPx after pretreatment with RG. It is possible that the free radicals generated by ISO were effectively removed, which suggests a protective effect of RG. Goyal et al. suggested that ischemic cardiac tissue generates ROS, which bring about contractile dysfunction, arrhythmias, and myocardium injury.34 Such changes were known to be representative of potential disagreement in the border between ischemic and nonischemic states and dysfunction of cardiac cell membrane.38 Whereas the present study demonstrated that the pretreatment with RG significantly inhibited the observed pathological ECG abnormalities of ST segments and QRS complex intervals, suggesting RG exerts a protective effect. In addition, in a previous study, ISO injection led to cardiac dysfunction, characterized by decreases in LVSP, +dP/dtmax, and −dP/dtmax.39 Whereas in the present study, the pretreatment of RG significantly inhibited the decreases of FS and EF as well as LVSP, +dP/dtmax, and −dP/dtmax. It was reported that NO in the cardiac tissue may trigger a preconditioning mechanism and decrease myocardial ischemia damage.40 In the present study, nitrite levels indicating NO generation were increased in the myocytes with the pretreatment of RG.31 This result suggests a preconditioning effect that contributes to the cardioprotection of RG. We also observed a significant increase of cTnI levels, a specific biomarker of cardiac damage,30 in the ISO-injected porcine. However, the pretreatment with RG decreased cTnI activity, further demonstrating the protective effects of RG. Also, in the present study, ISO injection induced a significant increase in MPO levels in the myocardium. However, the pretreatment with RG significantly decreased the elevated MPO levels, which indicates that RG inhibits neutrophil infiltration into myocardial tissue, suggesting further the cardioprotective effects of RG. In summary, the present study strongly demonstrates that a diversity of mechanisms may be responsible for the cardioprotective effects of RG. These beneficial potentials may be translated into biochemical and functional effects through antioxidant properties as evidenced by modulation of antioxidant enzymes by RG. In conclusion, the present study provides scientific rationale of the utility value of RG. However, further well-controlled prospective clinical studies need to be performed to ascertain whether present results can be applied in the treatment of human ischemic heart diseases.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2012R1A1A4A01011658), and by a grant from the Korean Society of Ginseng funded by Korean Ginseng Corporation (2011).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Ruff CT, Braunwald E: The evolving epidemiology of acute coronary syndromes. Nat Rev Cardiol 2011;8:140–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim JH: Cardiovascular diseases and Panax ginseng: a review on molecular mechanisms and medical applications. J Ginseng Res 2012;36:16–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dhalla NS, Elmoselhi AB, Hata T, Makino N: Status of myocardial antioxidants in ischemia-reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res 2000;47:446–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel V, Upaganlawar A, Zalawadia R, Balaraman R: Cardioprotective effect of melatonin against isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction in rats: a biochemical, electrocardiographic and histoarchitectural evaluation. Eur J Pharmacol 2010;644:160–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tinkel J, Hassanain H, Khouri SJ: Cardiovascular antioxidant therapy: a review of supplements, pharmacotherapies, and mechanisms. Cardiol Rev 2012;20:77–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singal PK, Yates JC, Beamish RE, Dhalla NS: Influence of reducing agent on adrenochromes induced changes in the heart. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1981;105:664–670 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graham DG, Tiffany SM, Bell WR, Gutkneth WF: Autoxidation versus covalent binding of quinines as the mechanism of toxicity of dopamine, 6-hydrxydopamine and related compounds toward C1300 neuroblastoma cells in vitro. Mol Pharmacol 1978;14:644–653 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ojha SK, Nandave M, Arora S, Narang R, Dinda AK, Arya DS: Chronic administration of Tribulus terrestris Linn. extract improves cardiac function and attenuates myocardial infarction in rats. Int J Pharmacol 2008;4:1–10 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rajadurai M, Stanely Mainzen Prince P: Preventive effect of naringin on lipid peroxides and antioxidants in isoproterenol-induced cardiotoxicity in Wistar rats: biochemical and histopathological evidences. Toxicology 2006;228:259–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rona G: Catecholamine cardiotoxicity. J Mol Cell Cardiol 1985;17:291–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Visioli F, Borsani L, Claudio G: Diet and prevention of coronary heart disease: the potential role of phytochemicals. Cardiovasc Res 2000;47:419–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hertog MG, Feskens EJ, Hollam PCH, Katan MB, Kromhout D: Dietary antioxidant flavonoids and risk of coronary heart diseases: the Zutphen Elderly Study. Lancet 1993;342:1007–1020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ignarro LJ, Balestrieri ML, Napoli C: Nutrition, physical activity, and cardiovascular disease: an update. Cardiovasc Res 2007;73:326–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee H, Kim J, Lee SY, Park JH, Hwang GS: Processed Panax ginseng, sun ginseng, decreases oxidative damage induced by tert-butyl hydroperoxide via regulation of antioxidant enzyme and anti-apoptotic molecules in HepG2 cells. J Ginseng Res 2012;36:248–255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamabe N, Song KI, Lee W, et al. : Chemical and free radical-scavenging activity changes of ginsenoside Re by Maillard reaction and its possible use as a renoprotective agent. J Ginseng Res 2012;36:256–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park JD: Recent studies on the chemical constituents of Korean ginseng (Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer). J Ginseng Res 1996;20:389–396 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kwon SW, Han SB, Park IH, Kim JM, Park MK, Park JH: Liquid chromatographic determination of less polar ginsenosides in processed ginseng. J Chromatogr A 2001;921:335–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Danuser H, Weiss R, Abel D, et al. : Systemic and topical drug administration in the pig ureter: effect of phosphodiesterase inhibitors alpha1, beta and beta2-adrenergic receptor agonists and antagonists on the frequency and amplitude of ureteral contractions. J Urol 2001;166:714–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soltysinska E, Olesen SP, Osadchii OE: Myocardial structural, contractile and electrophysiological changes in the guinea-pig heart failure model induced by chronic sympathetic activation. Exp Physiol 2011;96:647–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tian W, Xiaofeng Y, Shaochun Q, Huali X, Bing H, Dayuan S: Effect of ginsenoside Rb3 on myocardial injury and heart function impairment induced by isoproterenol in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 2010;636:121–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pada VS, Naik SR: Cardioprotective activity of Ginkgo biloba phytosomes in isoproterenol-induced myocardial necrosis in rats: a biochemical and histoarchitectural evaluation. Exp Toxicol Pathol 2008;60:397–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Osadchii OE, Norton GR, McKechnie R, Deftereos D, Woodiwiss AJ: Cardiac dilatation and pump dysfunction without intrinsic myocardial systolic failure following chronic beta adrenoreceptor activation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2007;292:H1898–H1905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ: Protein measurements with the folin-phenol reagent. J Biol Chem 1951;193:265–275 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Misra HP, Fridovich I: The oxidation of phenylhydrazine: superoxide and mechanisms. Biochemistry 1976;15:681–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aebi H: Catalase in vivo. Met Enzymol 1984;105:121–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paglia DE, Valentine WN: Studies on the quantitative and qualitative characterization of erythrocyte glutathione peroxidase. J Lab Clin Med 1967;70:158–169 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou R, Xu Q, Zheng P, Yan L, Zheng J, Dai G: Cardioprotective effect of fluvastatin on isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction in rat. Eur J Pharmacol 2008;86:244–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang GF, Satake M, Horita K: Spectrophotometric determination of nitrate and nitrite in water and some fruit samples using column preconcentration. Talanta 1998;46:671–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mullane KM, Kraemer R, Smith B: Myeloperoxidase activity as a quantitative assessment of neutrophil infiltration into ischemic myocardium. J Pharmacol Med 1985;14:157–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Brien PJ, Smith DE, Knechtel TJ, et al. : Cardiac troponin I is a sensitive, specific biomarker of cardiac injury in laboratory animals. Lab Anim 2006;40:153–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ikizler M, Erkasap N, Dernek S, Kural T, Kaygisiz Z: Dietary polyphenol quercetin protects rat hearts during reperfusion: enhanced antioxidant capacity with chronic treatment. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg 2007;7:404–410 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dhalla NS, Temsah RM, Netticadan T: Role of oxidative stress in cardiovascular diseases. J Hypertension 2000;18:655–673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ojha S, Nandave M, Arora S, Arya DS: Effect of isoproterenol on tissue defense enzymes, hemodynamic and left ventricular contractile function in rats. Indian J Clin Biochem 2010;25:357–361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goyal SN, Arora S, Sharma AK, et al. : Preventive effect of crocin of Crocus sativus on hemodynamic, biochemical, histopathological and ultrastuctural alterations in isoproterenol-induced cardiotoxicity in rats. Phytomedicine 2010;17:227–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou B, Wu LJ, Li LH, et al. : Silibinin protects against isoproterenol-induced rat cardiac myocyte injury through mitochondrial pathway after up-regulation of SIRT1. J Pharmacol Sci 2006;102:387–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim YS, Kim YH, Noh JR, Cho ES, Park JH, Son HY: Protective effect of Korean red ginseng against Aflatoxin B1-induced hepatotoxicity in rat. J Ginseng Res 2011;35:243–349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.He H, Xu J, Xu Y, Zhang C, Wang H, He Y, Wang T, Yuan D: Cardioprotective effects of saponins from Panax japonicus on acute myocardial ischemia against oxidative stress-triggered damage and cardiac cell death in rats. J Ethnopharmacol 2012;140:73–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ramesh CV, Malarvannan P, Jayakumar R, Jayasundar S, Puvanakrishnan R: Effect of a novel tetrapeptide derivative in a model of isoproterenol induced myocardial necrosis. Mol Cell Biochem 1998;187:173–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gupta SK, Mohanty I, Talwar KK, et al. : Cardioprotection from ischemia and reperfusion injury by Withania somnifera: a hemodynamic, biochemical and histopathological assessment. Mol Cell Biochem 2004;260:39–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qiu Y, Rizvi A, Tand XL, et al. : Nitric oxide triggers late preconditioning against myocardial infarction in conscious rabbits. Am J Physiol 1997;273:2931–2936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]