Abstract

Two-tone stimuli have traditionally been used to reveal regions of inhibition in auditory spectral receptive fields, particularly for neurons with low spontaneous rates. These techniques reveal how different frequencies excite or suppress the response to an excitatory frequency of a cell, but have often been assessed at a fixed masker–probe time interval. We used a variation of this methodology determine whether two-tone spectrotemporal interactions can account for rate-dependent directional selectivity for frequency modulations (FM) in the mustached bat inferior colliculus (IC). First, we quantified the response to upward and downward sweeping, linear, fixed-bandwidth FM tones centered at a unit’s characteristic frequency (CF) at 6 sweep durations ranging from 2 to 64 ms. Then, to examine how responses to instantaneous frequencies contained within the sweeps might interact in time, we varied the frequency and relative onset of a brief (4 ms) “conditioner” tone paired with a fixed 4-ms CF probe tone. We constructed “conditioned response areas” (CRA) depicting regions of suppression and facilitation of the probe tone caused by the conditioning tone. We classified the CRAs as predominantly excitatory (40.9%), inhibitory (22.7%), or mixed (36.4%). To generate FM response predictions, the CRAs were multiplied with spectrograms of the same sweeps used to assess response to FM. The predictions of FM rate and directionality were accurate by our criteria in approximately 20% of units. Conversely, the CRAs from the remaining units failed to predict FM responses as accurately, suggesting that most IC units respond differently to FM sweeps than they do to tone-pairs matched to the instantaneous frequencies contained in those sweeps. The implications of these results for models of FM directionality are discussed.

Keywords: Auditory midbrain, Frequency modulation, Spectrotemporal receptive field, Mustached bat, Neural delay lines, FM models, Temporal processing

1. Introduction

Frequency modulations (FM) are dynamic acoustic features found in most mammalian utterances, including human speech. The FM components in such sounds vary in dimensions such as modulation rate (rate of change of frequency over time), sweep direction (low to high, high to low), and depth (sweep bandwidth), and these salient acoustic features often differentiate between communication sounds. Studies in a variety of species have found neurons selective for FM direction and rate. Numerous conceptual models for FM rate and directional selectivity have been proposed, but few have been tested for their ability to predict responses to FM sounds quantitatively. More specifically, the temporal and spectral dependence of inhibitory and excitatory interactions thought to underlie preference for rate and direction of FM are not clearly understood.

Classical models propose that directionality arises from either suppression of responses to sweeps in the non-preferred (null) direction, facilitation of responses to sweeps in the preferred direction, or both. Suppression of null-direction sweeps has been attributed to asymmetrical inhibitory sidebands in the spectral receptive field in a number of studies (Fuzessery, 1994; Fuzessery and Hall, 1996; Heil et al., 1992b; Shannon-Hartman et al., 1992; Suga, 1965b; Suga et al., 1974; Gordon and O’Neill, 1998). Facilitation in the preferred sweep direction is less well documented, but has been modeled by some as temporally dependent dendritic spatial summation (Erulkar et al., 1968; Fuzessery and Hall, 1996; Heil et al., 1992b; Poon et al., 1992).

Directional preferences for FM sweeps arise in the cochlear nucleus (Britt and Starr, 1976; Erulkar et al., 1968), and are well documented in studies in the auditory midbrain. In previous work in the mustached bat inferior colliculus (IC), we demonstrated that directionality was mainly attributable to suppression by null-direction sweeps, and that the “maximally rejected” rate and direction were significantly correlated with a “best inhibitory delay” revealed by two-tone interactions modeling the tonal components of the FM sweep (Gordon and O’Neill, 1998). The results showed that the timing, and not simply the presence, of sideband inhibition is a critical determinant of FM directionality, and that this could account for the fact that directional preferences are often evident only over a certain range of modulation rates. In a subsequent study of directional preferences in the suprageniculate nucleus of the medial geniculate body, we showed that directionality involved not only suppression by sweeps in the null-direction, but also facilitation by sweeps in the preferred direction (O’Neill and Brimijoin, 2002).

Although many studies have correlated directional selectivity with spectral response areas obtained with two-tone-stimuli (Fuzessery, 1994; Gordon and O’Neill, 1998; Shannon-Hartman et al., 1992; Suga, 1965a), these earlier studies varied the conditioning stimulus (masker) along only one dimension (frequency or time) while holding the other dimension constant, and made no attempt to predict FM responses quantitatively. In the current study, we recorded single units in a portion of the central nucleus of the IC that is tuned to the second harmonic (∼59 kHz) of the bat’s FM-containing biosonar call, as well as in a similarly tuned region in the ventral division of the external nucleus of the IC (ICXv) where units were shown to be directionally selective (Gordon and O’Neill, 2000). To better our understanding of the spectrotemporal interactions underlying directional selectivity, we expanded the aforementioned two-tone forward masking procedure by extending the analysis in the spectral as well as the temporal domain. By varying one tone (the conditioner) along two dimensions, viz. interstimulus onset time interval and frequency, relative to a pure-tone probe fixed at the CF, we constructed a conditioned response area (CRA) that elucidates the local spectral and temporal interactions that may be relevant for the coding of FM sweeps. This method shares much in common with that used by Brosch et al. (1999), but is measured with higher resolution over a narrower range of frequencies and relative onset times than has been previously attempted. To test the possibility that the CRA measures response properties related to selectivity for FM sweep dimensions, we used the CRA obtained for each unit to predict responses to a set of biologically relevant linear FM sweeps, and compared the predictions to that unit’s actual responses to those same sweeps.

2. Methods

2.1. Preparation

Recordings were made from 4 wild-caught male Trinidadian mustached bats (Pteronotus parnelli rubiginosus). All husbandry, surgery, and experimental procedures were approved by the University Committee on Animal Resources. Bats were housed in a temperature (24 °C) and relative humidity (80%) controlled flight room and fed fortified mealworms. Surgery to mount a head-restraining post, implant an indifferent electrode, and expose the IC was performed under methoxyflurane anesthesia (Metofane, Pittman-Moore) using techniques described previously (O’Neill, 1985). For the experiments, awake bats were administered a low dose of an opioid agonist (butorphanol tartrate, 0.7 mg/kg i.p.; Abbot Laboratories, North Chicago, IL), and restrained painlessly in a stereotactic frame (Schuller et al., 1986). Single unit recordings were made in the IC on the left side exclusively, using sharpened 1 M Na+ acetate-filled glass micropipettes with tip impedances ranging from 9 to 12 MX. The recorded potentials were referenced to a tungsten indifferent electrode embedded in the skull in contact with the dura, contralateral to the recording site. Recordings in each bat were made over a 4–6-week period, 2–3 days/week, in 4–6 h sessions.

2.2. Sound generation and presentation

All acoustical stimuli were presented through a 3.75-cm diameter electrostatic transducer (model T2004C; Polaroid Corp., Cambridge, MA) placed 17 cm from the bat’s head along the acoustic axis of the pinna at 60 kHz (25° from the midline contralateral to the recording site in the horizontal plane of the stereotactic frame).

Stimuli were digitally synthesized with a sample period of 2.96 µs in SigGen32© (Tucker–Davis Technologies, Alachua, FL) and presented using TDT System II hardware (Tucker–Davis Technologies, Alachua, FL) controlled by custom C++ software running on a PC under Windows 2000© (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA). Spike acquisition was also performed under program control with the same hardware. Extracellularly recorded waveforms were first amplified (Dagan model 2400; Minneapolis, MN), filtered (450 Hz–4.5 kHz; TDT SC1), and single units were isolated from background based on consistent waveform shape and amplitude (TDT SD1 spike discriminator). Accepted spikes were time stamped (TDT ET1 event timer), and spike times were stored along with information about the stimulus in a relational database (Access©, Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA).

The system’s maximum sound pressure level (SPL, dB re 20 µPa) was calibrated using SigCal32© software (TDT Technologies). Signals were recorded at the subject’s head using a 1/4′′ condenser microphone (Bruel and Kjær type 4135) and measuring amplifier (Bruel and Kjær model 2610). Maximum speaker output ranged from 93- to 97-dB peak equivalent SPL over the 50- to 75-kHz frequency band of the stimuli presented.

2.3. Experimental procedure

Sinewave search stimuli were generated with a voltage-controlled waveform generator (Wavetek 111; San Diego, CA), gated and shaped with a programmable electronic switch (Wilsonics BSIT; San Diego, CA) into 30 ms tone bursts with a rise-fall time of 0.5 ms (cos2 ). Search stimulus level was controlled with a programmable attenuator (Wilsonics PATT; San Diego, CA). Using tone bursts, CF was measured at minimum threshold (MT) for each unit audiovisually. The unit was then tested with 12 kHz bandwidth, upward and downward FM sweeps centered on the CF of the cell, 20 dB above MT. Linear FM sweeps were generated by applying a voltage ramp to the VCG input of the voltage-controlled generator. This methodology selected for cells that responded to both tones and FM sweeps, and thereby may have missed “FM specialized” units that respond to FM sweeps but not to tones. While FM specialized units are relatively common in the IC of some species of bats, such units comprise less than 2% of ICC and ICXv units in the mustached bat (O’Neill, 1985; Gordon and O’Neill, 2000). Once preliminary measures were obtained, we tested the unit using an FM stimulus set followed by presentation of a two-tone stimulus set for constructing the conditioned response area.

2.4. FM stimulus set

Responses were quantified using a four-component stimulus train (e.g., Fig. 1) containing (1) a pure tone at the unit’s CF, (2) an upsweeping FM, (3) a down-sweeping FM, and (4) a narrow-band (NB) noise burst. The FM sweeps and NB noise bursts had fixed band-widths of 12-, or in some cases, 6 kHz, always centered at CF. Each component was shaped (cos2 ) with a rise-fall time of 0.5 ms, and the interstimulus onset interval was 200 ms. By necessity, stimulus duration and sweep rate co-vary in fixed-bandwidth FM sweeps. Because a high percentage of IC units can be selective for stimulus duration (Brand et al., 2000; Casseday et al., 1994), it is possible to confound selectivity for FM sweep rate with selectivity for FM (or stimulus) duration. To avoid this problem, the initial tonal stimulus served both as a control for stimulus duration, as well as a stimulus for determining the magnitude and latency of response at CF (see below). The NB noise burst was intended as a control for both duration and bandwidth, as the noise bursts lacked the temporal structure of the FM sweeps, but matched their long-term spectrum.

Fig. 1.

Responses to the stimulus set consisting of (from left to right) a CF tone burst (tone), upward FM sweep (FM up), downward FM sweep (FM down), and narrow band noise burst (NB noise). The raster plots are ordered by increasing stimulus duration from top (2 ms) to bottom (64 ms). Each dot in the raster display indicates the occurrence of a single spike. Shaded bars are schematic frequency–time spectrograms of the stimuli used to drive the cell. This unit showed an onset response to CF tones regardless of tone duration. It responded poorly to NB noise bursts regardless of duration. It had significant directional selectivity for upsweeps with durations between 8 and 32 ms, but responded better to downsweeping FM at the shortest FM duration (2 ms). The unit did not respond to the longest sweep duration presented (64 ms). Latency was locked to the onset of pure tone stimuli, but varied systematically with the duration (sweep rate) of FM (see Fig. 2(a)).

The components were presented in a geometric series of six durations: 64, 32, 16, 8, 4, and 2 ms to vary the sweep rate of the FM sweeps. For the 12 kHz bandwidth sweep, this yielded FM rates of 0.188, 0.375, 0.750, 1.50, 3.0 and 6.0 kHz/ms, respectively. For the 6 kHz bandwidth, the rates were 0.094, 0.188, 0.375, 0.750, 1.50 and 3.0 kHz/ms, respectively. Trains at each duration were repeated 25 times to obtain spike counts. The 12 kHz bandwidth, 3.0 kHz/ms downsweep matches closely the second harmonic terminal FM sweep in the mustached bat biosonar call emitted during the search phase of echolocation. The other rates span the range of FM components found in mustached bat communication sounds (Kanwal et al., 1994). Sweep amplitude does not strongly affect directional selectivity (O’Neill and Brimijoin, 2002; O’Neill et al., 2003). In this study, stimuli were presented at 10–20 dB above MT. FM responses are quantified as mean ± SEM spikes per presentation.

For both the 12- and 6-kHz sweeps, directional preferences at each modulation rate were quantified with the conventional directional selectivity index (DS) used in many previous studies: DS = (U – D)/(U+ D), where U and D are the spike counts in response to upward and downward FM sweeps, respectively (Britt and Starr, 1976; Gordon and O’Neill, 1998; Heil and Irvine, 1998; Mendelson and Cynader, 1985). Significant directionality is defined as twice the number of spikes in response to one sweep direction over the other, corresponding to an absolute DS index ≥ 0.333. As low spike counts can produce erroneously high DS indices, neurons with response probabilities under 0.2 (5 spikes per 25 presentations) in the best sweep direction were excluded from the analysis.

2.5. Calculation of median first spike latencies

The median first spike latency (FSL) for tones and FM sweeps was also measured using the FM stimulus set. For each stimulus duration, median FSL was calculated from the first spike occurring after stimulus onset, corrected for the acoustic delay between the loudspeaker and the bat (0.513 ms). For FM sweeps, the FSL vs. duration function was used to determine the instantaneous effective frequency (EFi) in the sweep. The growth (slope) of the latency vs. duration function would depend on the time of occurrence of the EFi in the sweep, progressively increasing from 0 if EFi equals the initial frequency in the sweep, to a maximum of 1 if EFi equals the terminal frequency in the sweep. FM and CF latencies for stimuli of equal duration would be related by the linear equation LFM = LCF + 1/2D, where LFM is the latency for the FM sweep (centered on CF), LCF is the latency for the CF tone, and D is the duration of the stimulus. Deviations of the slope below or above 0.5 would suggest that the response to FM is triggered by a frequency occurring earlier or later than the CF in the sweep, respectively, because the CF was centered in the sweep.

2.6. Generation of conditioned response area

While our method shares much in common with a study of responses to tone sequences in the auditory cortex by Brosch et al. (1999), the frequencies and onset intervals spanned a much smaller range relevant to the encoding of rapid FM sweeps of interest here. Our objective was to test directly a basic two-input model of FM selectivity, namely that the response to FM sweeps can be predicted by the interaction in time of two inputs, one at the CF and the other at or near the CF. A two-tone stimulus was used to generate a two-dimensional (frequency vs. time) conditioned response area (CRA). Because CRAs showed evidence of both suppression and facilitation, we use the term conditioned rather than masked response area to avoid the connotation of a purely suppressive interaction. Data for the CRA were obtained by repeatedly presenting a three component stimulus (Fig. 2(a)) consisting of a roving conditioning tone (“conditioner”), paired with a CF probe tone, followed by the conditioning tone alone, and finally the probe tone alone, each component separated by 200 ms. Both conditioner and probe tones were 4 ms in duration, shaped (cos2) with a rise-fall time of 0.5 ms. The probe tone was fixed at the CF and presented at a level above MT that evoked reliable, but not maximal, responses (typically MT + 20 dB). The conditioner amplitude always equaled that of the probe. The initial probe tone was presented 32 ms after the onset of each data acquisition period (or “epoch”). The conditioning tone was iterated through 9 onset times in 4-ms steps, ranging from −32 to 0 ms re probe onset; and 13 frequencies ranging from −6 to +6 kHz re probe frequency in 1 kHz steps. The conditioning tone was thereby stepped through a range of frequencies 12 kHz wide and a pre-probe time window 32 ms long. Each stimulus condition was repeated 5–10 times to obtain spike counts.

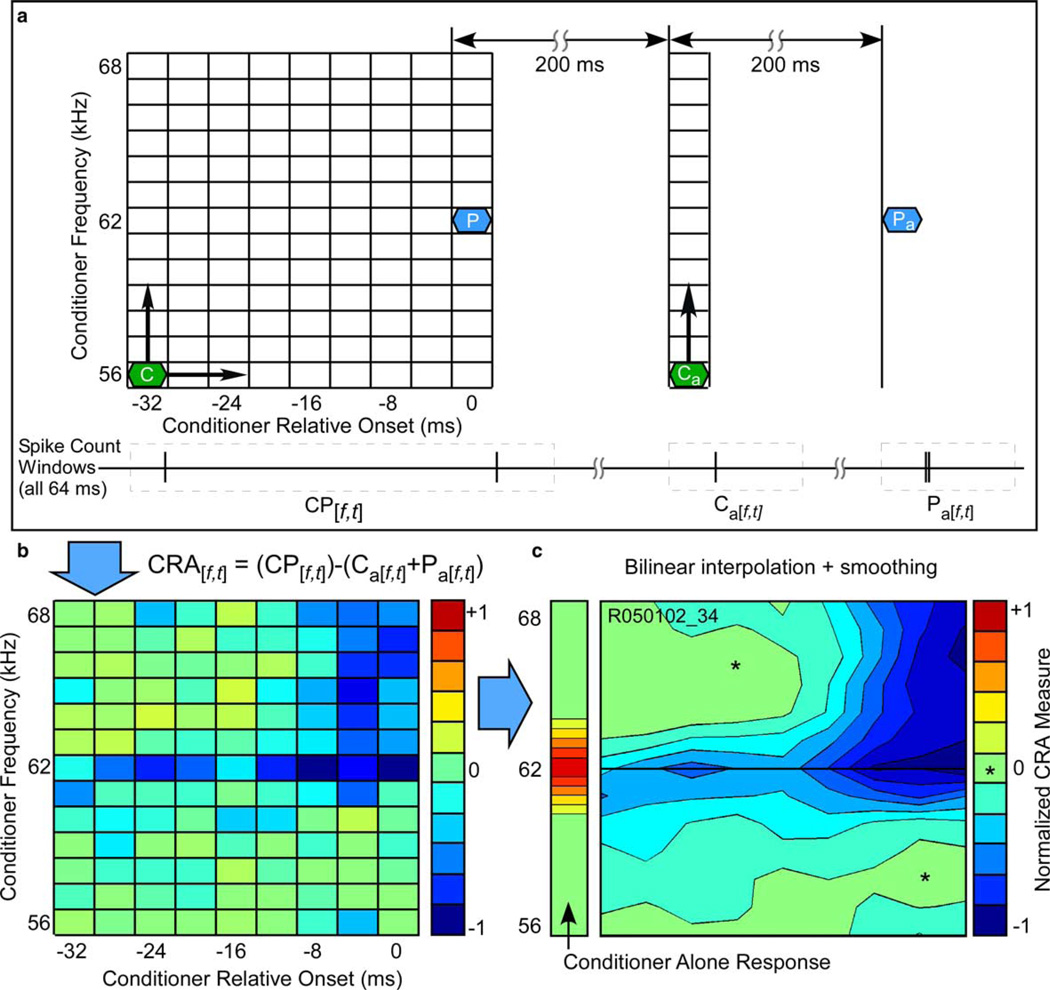

Fig. 2.

Generation of the conditioned response area (CRA). (a) A schematic ΔF, ΔT matrix of the stimulus set used to generate the CRA. The probe tone (P) is fixed at CF and is preceded by a conditioning tone (C) of variable frequency and onset time. The paired tones are followed, first by an isolated conditioning tone and then by an isolated probe tone, at intervals of 200 ms. Spikes (vertical lines) are counted in windows (dotted lines) including the probe tone paired with the conditioning tone (CP[f,t]), the isolated conditioning tone (Ca[f,t]), and the isolated probe tone (Pa[f,t]). (b) The CRA[f,t] is a matrix of coefficients that quantify the degree of facilitation (positive values) and suppression (negative values) of the probe-alone response as a function of the frequency and relative onset of the conditioning tone. (c) CRA coefficients in (b) are smoothed, interpolated and plotted in grayscale contours as a ΔF vs. ΔT graph. The contour line corresponding to no change from probe alone is indicated with an asterisk (*). Note for this unit the diffuse weak-to-moderate on-CF suppression (CF denoted by a horizontal line) and the large, strong, and temporally restricted suppressive area above the CF.

During each stimulus epoch, spikes were counted in four count windows (cf. Fig. 2(a)): window 1, 0–64 ms, counting spikes elicited by the roving conditioning tone paired with the probe tone presented at 32 ms; window 2, 132–164 ms, conditioning tone alone; and window 3, 232–264 ms, probe tone alone. For each combination of conditioning tone frequency and onset interval, activity was calculated as the difference between the probe response in the presence of the conditioner (window 1) less the sum of the conditioner- and probe-alone responses (window 2 + window 3) according to the following formula:

where CP[f,t] is the frequency/time matrix of spike counts in response to the probe tone paired with the conditioning tone (window 1), Pa[f,t] is the spike count matrix in response to the probe alone, and Ca[f,t] is the spike count matrix in response to the conditioner alone. The result is a measure of suppression (negative numbers) and/or facilitation (positive numbers) of the probe response by the conditioning tone as a function of frequency and time. The conditioning tone alone response (window 2) was also used to measure the excitatory response area (measured 20 dB above tone threshold). The bandwidth of this excitatory area was defined as the difference between the lowest and highest frequency bin that elicited a response above background, and from this we estimated tuning sharpness by computing a Quality factor (Q20dB = CF ÷ bandwidth). It is important to note that the resolution of the excitatory area boundaries is limited to 1 kHz by the frequency steps of the conditioning tone, as well as the 12 kHz CRA bandwidth limit.

2.7. Visualization and categorization of CRAs

Analysis of the CRA data was performed using Matlab 6.0 (The Mathworks, Inc., Natick, MA). For the purposes of visualization, CRAs were plotted on a contour map as a function of both frequency of the conditioning tone and conditioner-probe time interval. To reduce the effect of random fluctuations in spike counts, the CRAs were smoothed using a method adapted from Davis et al. (1995). For matrices with fine resolution, smoothing typically involves convolution with a 3 × 3 kernel of ones; that is, for any given cell of the frequency–time matrix, the spike count is simply averaged with those of the 8 nearest-neighboring cells, all equally weighted. However, due to the coarseness of CRA sampling in the time domain (4 ms) and the brief 4-ms FM sweeps used in our experiments, we found that this equally weighted smoothing matrix lost too much detail and thereby degraded the accuracy of predictions. To counter this problem, we systematically de-emphasized the smoothing kernel surround values until an optimal compromise was found between retention of detail in the CRA and noise reduction. The resultant center-weighted 3×3 kernel had a value of 1.0 in the center, and 0.25 in the surrounding 8 cells. After smoothing, the CRAs were interpolated (Fig. 2(c)) at a finer scale (bilinear interpolation, 1024 frequency × 512 time intervals) to match the resolution of the spectrograms of the FM sweeps (see below).

2.8. Prediction of FM responses

Frequency–time spectrograms of the FM stimuli were generated at the same resolution as the up-sampled CRAs (1024 × 512 frequency vs. time) for the sweeps at 20 combinations of rates (5), directions (2), and bandwidths (2) comprising the FM stimulus set. The fastest sweep (2 ms) was omitted because it and the 4 ms sweep fell within the 4 ms time resolution of the CRA. The spectrograms were time shifted to compensate for the temporal offset introduced by the width of the FFT window (1024 points). CRAs were multiplied with the remaining five spectrograms of the sweeps used in the FM stimulus set (Fig. 3(a), left). CRAs that vary from 0 (no conditioner effect on probe) to −1 (strong suppression) yield uniformly negative FM spike count predictions. Therefore, all such CRAs were offset by the most negative value prior to prediction. This methodology is based on the principle of the matched spatial filter as applied to the spectrotemporal domain. Since the smoothed and up-sampled CRA is specified in the spectrotemporal domain using the same dimensions as the Fourier transforms of the FM sweeps, point-by-point multiplication allows us to find the FM sweep with spectral and temporal properties most similar to the spectral and temporal features of the given CRA. Any benefits of transforming the CRA for convolution with the original FM signal are outweighed by the smaller resultant kernel and the fact that mustached bat IC unit responses tend to be phasic onset (often 1 spike per trial), and as such, reconstructing response time-course is unnecessary.

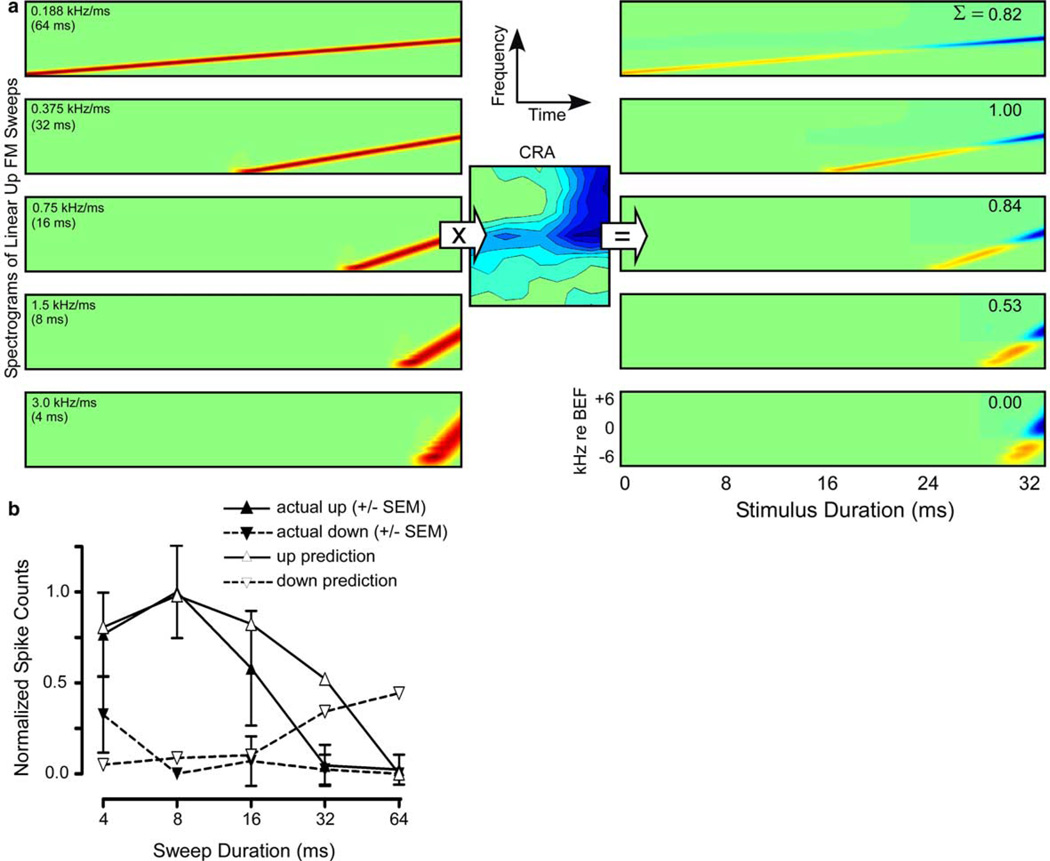

Fig. 3.

Generation of FM sweep response predictions: (a) Spectrograms of each rate and direction of FM sweep in the FM stimulus set were point-by-point multiplied with the CRAs (only the initial half of the sweep prior to the CF was used). The CRA/FM spectrogram products were summed and normalized to yield predicted quantitative output coefficients for each sweep rate and direction (upsweep coefficients shown in upper right corner of each spectrograph). All negative output coefficients were replaced with zeros. (b) Predicted vs. actual normalized responses from the FM stimulus set for the same cell shown in Figs. 1, 2, and 4(a). In this unit, the predictions matched the actual responses closely for upward FM sweeps, falling within one SEM of the mean (error bars) for all but the 32 ms sweep duration. For downward FM sweeps, the prediction was correct for only one of the durations tested (16 ms). However, overall directionality is correct.

To quantify the prediction for a given sweep, the products of the smoothed time-adjusted spectrograms and the CRAs were summed across both the time and frequency domains (Fig. 3(a), right). Predictions were normalized in two stages. First, to compensate for the difference in total power between sweeps of different durations, normalization coefficients were generated for each sweep duration and direction by multiplying the frequency–time spectrogram for each sweep point-by-point with a uniform (featureless) CRA composed of a matrix of ones, and then summing to produce a predicted output (a process identical to the prediction process). The predicted output for each sweep rate and direction was divided by its corresponding normalization coefficient to equate power. Second, the set of predictions was divided by the predicted maximum value. In this way, the ideal FM sweep, i.e., the sweep that matched best the spectral and temporal features of the CRA, yielded a predicted output of 1, and the predictions for the remaining FM sweeps were scaled relative to that ideal FM sweep.

2.9. Tests of predictions

CRA predictions were compared with actual responses to FM sweeps to test for accuracy. Upsweeps and downsweeps were considered separately. Mean and standard errors of the number of spikes per presentation were calculated from the responses to the FM stimulus set and normalized to the rate and direction evoking maximal response. For a given FM rate and direction, a successful CRA-generated prediction had a value within ±1 SEM and overall predictions were judged to be successful if they were within one SEM for four out of five sweeps. Note that the SEM is a particularly stringent criterion for successful prediction.

2.10. Histology and localization of recording sites

Recording sites were verified histologically by making a local iontophoretic injection of biotinylated dextran amine (BDA, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR; 10% sol. in sterile saline) by applying a 3 µA constant DC current (CS-3 current source, Midgard Electronics, Canton, MA) for 5 min at 50% duty cycle (7-s on, 7-s off) through the recording micropipette (10 µm tip diameter). After a 1–2 week survival time, the animals were sacrificed with an IP overdose of sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg) and perfused intracardially with buffered 4% paraformaldehyde in sterile saline. The brains were removed and blocked in agarose gel in the standard position of the stereotaxic atlas (Radtke-Schuller, unpublished) and sectioned on a cryostat at −18 °C(Frigocut 2800e, Leica-Jung, Germany) at 30 µm intervals. BDA injection sites were visualized by incubating the sections with a Neurotrace BDA-10,000 kit (Molecular Probes). After mounting the sections and counterstaining, the location of the injection site was determined relative to the stereotaxic coordinate system. Unit coordinates were corrected relative to the localization of the injection site. All units reported in this paper were localized to the anterolateral division of the central nucleus (ICC) or the ventral division of the external nucleus (ICXv) of the inferior colliculus (IC).

3. Results

3.1. General results

We isolated and studied 58 units in the ICXv and ICC. The mean CF for these units was 59.08 ± 6.8 kHz (SEM). Mean minimum threshold (MT) was 11.55 ± 1.3 dB SPL (SEM). Mean excitatory response area bandwidth at MT + 20 dB was 4.8 ± 0.53 kHz (SEM), yielding a mean Q20 dB of 16.1.

Nearly all units (93%) exhibited a very brief phasic-on response to both tones and FM sweeps, typically firing 1–3 action potentials per stimulus presentation regardless of duration. Phasic-on units responded with a nearly invariant latency to CF tones and NB noise, however, latency to CF-centered FM sweeps typically varied systematically with sweep duration (i.e., modulation rate).

Of the 43 units with complete FM stimulus data sets, 38 (88.4%) were significantly directional (absolute DS Index ≥ 0.33) at one or more sweep rates. 73% of these directionally selective units preferred upsweeps over downsweeps. Since IC neurons often express directionality over a limited range of sweep rates, overall directionality was defined as the direction preferred in the majority of sweep rates tested. The median absolute DS index values varied with FM bandwidth, tended to be maximal for the slowest sweep rate, and typically declined with increasing sweep rate (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Median DS indicesa

| Bandwidth (kHz) | Sweep duration (ms) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 64 | 32 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 2 | Mean | |

| 6 | 0.47 | 0.41 | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.20 | 0.11 | 0.31 |

| 12 | 0.54 | 0.31 | 0.38 | 0.46 | 0.24 | 0.14 | 0.35 |

Absolute values.

Fig. 1 is a dot-raster plot of the response of a directionally selective IC unit to the 12 kHz FM stimulus set, ordered from the top by increasing duration. Horizontal lines separate each block of 25 presentations for each stimulus duration. The superimposed shaded bars are schematic frequency/time spectrograms of the stimuli indicating the timing of the stimuli relative to the responses. The unit responded reliably and with a single, nearly constant-latency to CF tone onsets regardless of duration, but was driven poorly by NB noise bursts of the same average level. Latency for FM sweeps was similarly consistent within each block, but shifted systematically with increasing duration of the sweep. This unit is a good example of how directionality can be dependent on sweep rate. The unit was significantly directionally selective for upward FM at 3 of the 6 durations (8, 16 and 32 ms). Responses were poor for the longest FM sweeps (64 ms), regardless of sweep direction, whereas for the shortest (2 ms) sweeps, the unit showed a reversal in selectivity, preferring downward rather than upward sweeps.

3.2. Types of rate selectivity

Based on their response/rate functions for the preferred direction of FM, units were separated into four general categories. Low-pass units (41.7%) responded best at the slowest sweep rates tested. High-pass units (4.2%) responded best at the fastest rates. Band-pass units (47.9%) responded most at an intermediate rate or range of rates tested. All-pass units (6.3%) responded more or less equally at all rates tested. Clearly, the vast majority (89.6%) of the units fell into the low- and bandpass categories.

3.3. First-spike latency and instantaneous effective frequency

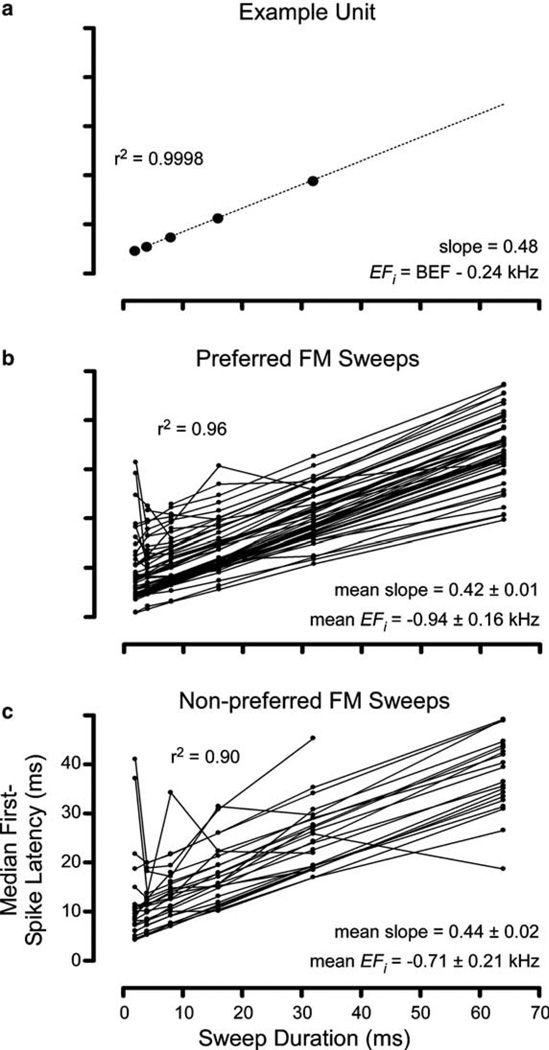

For fixed-bandwidth sweeps, median first spike latency (FSL) tended to increase with increasing sweep duration. The graphs in Fig. 4 plot median FSL against sweep duration. For the example unit described previously in Fig. 1, FSL for preferred direction sweeps increased linearly (r2 = 0.9998) as a function of sweep duration (Fig. 2(a)), with a slope of 0.48. Similarly, for the population of sampled units (Fig. 4(b)) the increase in latency with sweep duration is highly linear for preferred sweeps (mean r2 = 0.96). A linear increase in response latency would result if the response were elicited by a single effective frequency (EFi) in the sweep (Bodenhamer et al., 1979). For 12 kHz-bandwidth sweeps in the preferred direction, the slope of the latency growth function averaged across all units was 0.42 ± 0.01, which translates to an EFi of 0.94 ± 0.16 kHz prior to CF in the sweep. For sweeps in the null-direction (Fig. 4(c)), the increase in latency is less linear (median r2 = 0.90). Mean slope of the latency change is 0.44 ± 0.02, yielding an EFi of 0.71 ± 0.21 kHz prior to CF. Thus, the EFi for sweeps in both directions in nearly all units just precedes the CF by under 1 kHz. Some studies of FM processing in cat auditory cortex have implicated the excitatory response area border as the EFi for preferred direction sweeps (Heil and Irvine, 1998; Tian and Rauschecker, 1994; Tian and Rauschecker, 1998), or the steepest rising portion of the spike-count vs. frequency curve of the response area (Heil, 1997). Because the units in our study were very sharply tuned, we cannot completely rule out either of these possibilities. However, the calculated EFi was well within the bandwidth of the excitatory areas at the level we measured them (4.8 ± 0.53 kHz, mean ± SEM).

Fig. 4.

Median first-spike latency as a function of duration. (a) For the example unit from Fig. 1, median FSL increased linearly (r2 = 0.9998) as a function of sweep duration in the preferred (upward) sweep direction. The linear regression line fit to the data is displayed (dotted line). (b) FSLs for all units to preferred-direction sweeps in as a function of sweep duration. Increase in FSL with sweep duration was linear (mean r2 = 0.96) with a mean slope of 0.42 ± 0.01 (SD), indicating that the EFi is on average 0.94 ± 0.16 kHz prior to the occurrence of the CF in the sweep. (c) FSLs for all units to non-preferred sweep direction: increase in latency is linear (mean r2 = 0.90) with a slope of 0.44 ± 0.02, yielding an EFi of 0.71 ± 0.21 kHz prior to CF.

3.4. Summary statistics and qualitative features of CRAs

In order to examine the spectral and temporal features of local excitatory and inhibitory interactions that might influence response to FM sweeps, we obtained CRAs using the two-tone “masking” paradigm. Because responses elicited by FM sweeps appear to be triggered by an EFi very close to the CF, it was appropriate for us to use CF tones as the probe stimulus in the two-tone paradigm used to construct the CRA. An example CRA is shown in Fig. 2, which also illustrates the methods used to construct it. To generate the CRA, a probe tone (P) at the CF was paired with a conditioning tone (C) varied in frequency and onset relative to the probe (Fig. 2(a)). In this paradigm, spikes in response to the isolated probe and the isolated conditioning tone were subtracted from spikes counted in response to the paired probe and conditioning tones (Fig. 2(b)). Negative values indicate that the response to the probe paired with the conditioning tone was suppressed, i.e., less than the sum of the conditioner and probe presented alone; and positive values indicate that the conditioning tone had a facilitative (super-additive) effect on the probe response, i.e., greater than the sum of the conditioner and probe alone. The contour line corresponding to a CRA value of zero (no effect of the conditioner) is indicated with an asterisk. In this particular example, the CRA shows a spectrally broad, but temporally restricted, region of inhibition at frequencies above CF (Fig. 2(c)).

CRAs were categorized into four groups: facilitated, suppressed, mixed (in which the response areas contained clearly defined regions of both facilitation and suppression), and unresolvable (in which the spike counts were too low for analysis, usually because the neuron did not respond to the short duration tones used to generate the CRAs). Suppressive regions were defined as a decrease in the probe response when paired with the conditioning tone; no direct claims are made about the neural (central) and/or bio-mechanical (peripheral) bases of this suppression. Unresolvable CRAs (n = 10) were excluded from further analysis Of the resolvable CRAs (n = 45), 40.0% were facilitated, 22.2% suppressed, and 37.8% mixed.

3.5. Size and shape of CRAs

For quantification, regions of facilitation and suppression were delineated manually in Matlab using higher resolution contour plots than are included in the published figures. The contour lines corresponding to the background level of the CRAs were identified and the edges of suppressive or facilitatory regions were demarcated using “mouse position capture” on the corresponding contour lines. The dimensions were statistically analyzed in Prism© 4.0 (Graphpad, San Diego, CA) using Welch’s correction for unequal variances. The size of the subfields in the CRAs can be described in both the temporal and the spectral dimensions. Facilitatory subfields tended to be larger than the suppressive subfields (T[66] = 2.47, p < 0.05), The difference was mainly in the time domain. Suppressive subfields far outlasted the conditioning tone, but nevertheless were brief in absolute terms (average 10.78 ms) and were often most potent at or near the onset of the probe tone. Facilitatory subfields were on average even longer (15.78 ms), often extending from simultaneous onset (Δt = 0) out to the maximum conditioner/probe interval (Δt = 32 ms). The difference in the duration of facilitatory and suppressive subfields was significant (T[66] = 2.8, p < 0.01). By contrast, there was no significant difference in the spectral domain (mean bandwidth 3.6 kHz, T[66] = 0.25, p = 0.80).

3.6. Prediction of FM responses

Predictions and the method used to calculate them are shown in Fig. 3 for the example unit from Figs. 1–3. CRAs were point-by-point multiplied with spectrograms of the first half of the FM sweeps used in the study to yield a measure of shared spectral energy (Fig. 3(a), left). The matrix products were summed to yield a prediction for each frequency sweep (Fig. 3(a), right). Predictions were normalized to their maximum. In this way, the FM sweep that bore the most spectrotemporal similarity to the CRA yielded a prediction of 1.0, and other sweeps were scaled relative to this maximum. The CRA predictions were compared with normalized spike counts in response to the same FM sweeps (Fig. 3(b)). In this unit, the CRA accurately predicted both overall directionality (up-selective) and overall sweep rate selectivity (low-pass), and the prediction for upsweeps differed significantly from the actual response to FM only at one sweep duration (32 ms).

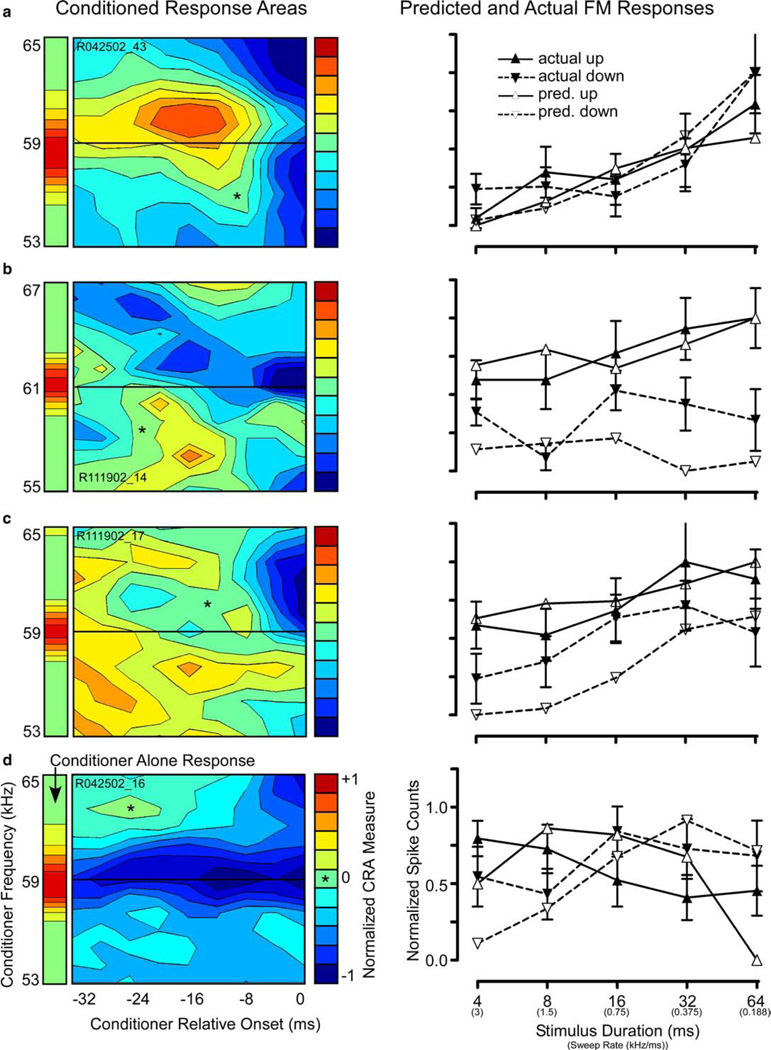

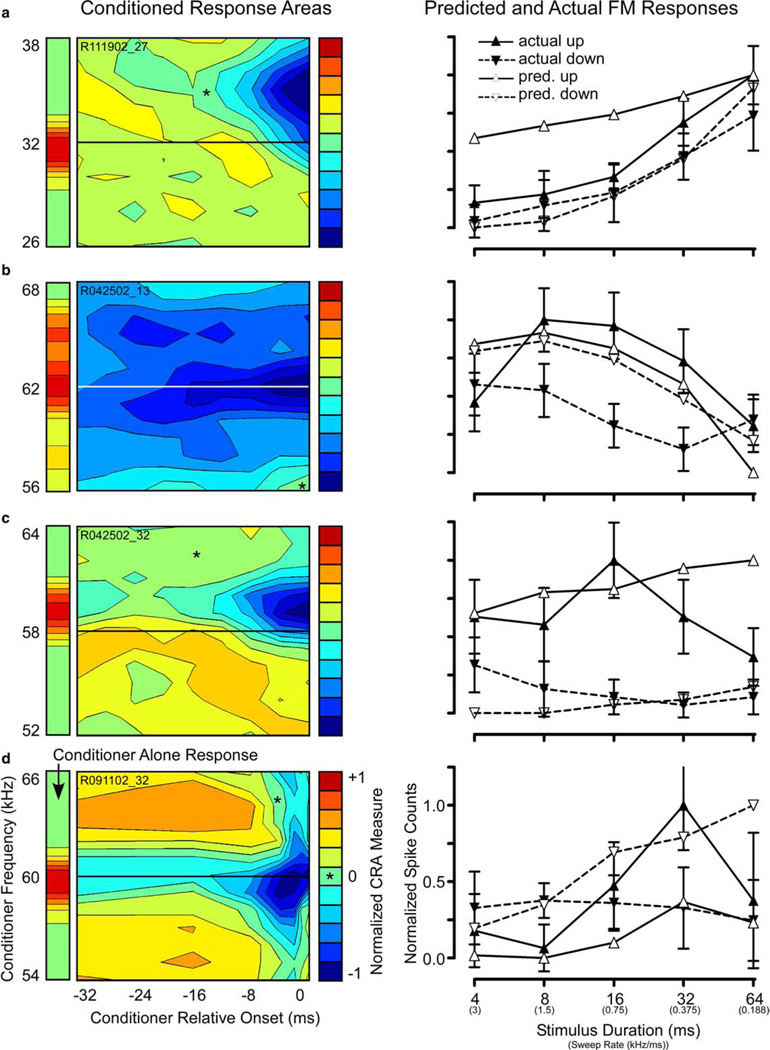

Additional examples of CRAs yielding accurate predictions are shown in Fig. 5. The CRA of a non-directional unit (Fig. 5(a)) exhibited a large symmetric region of facilitation centered at CF 16 ms prior to probe onset, surrounded by widespread suppression. As expected from the lack of spectrotemporal asymmetry in the CRA, the unit showed no directional preference for FM (right panel).

Fig. 5.

Selected examples of CRAs (left column) that successfully predicted actual FM sweep results (right column): (a) CRA from a non-directional unit was nearly symmetrical around the CF with areas of facilitation and suppression above and below. The predicted FM response profile (right) was correspondingly non-directional and correctly predicted the actual selectivity for slow FM rates. (b) Up-selective unit with a spectrally asymmetrical CRA, showing facilitation below and strong suppression above CF (left). The CRA-predicted preference for slow upsweeping FM matches the actual FM response profile (right). However, the CRA underestimated the response to downsweeping FM at nearly all sweep rates tested. (c) Up-selective unit with a brief, short-latency, broadband region of suppression above CF and a diffuse, long-duration region of facilitation below. The CRA correctly predicted a significant preference for upsweeping FM at all sweep durations except 32 and 64 ms, and correctly estimated the duration at which the maximum response was evoked (8 ms). However, the CRA underestimated the response to downsweeps at all but the longest sweep durations. (d) Unit with a rate-dependent reversal in FM directional selectivity. The CRA contained a strong, long-lasting trough of suppression centered at the CF, and a temporally dependent region of inhibition that was strongest at the shortest delays and decreased to no inhibition (*) at the longest delays. The spectral and temporal asymmetry of the CRA correctly predicted a rate-dependent directional selectivity. However, the prediction fell within ±1 SEM for only a few sweep rates, and also incorrectly estimated the rate at which the reversal in directional preference occurred.

By contrast, a low-pass, up-selective unit shows clear spectral asymmetry (Fig. 5(b)). In addition to on-CF suppression, this CRA contained a short-duration area of facilitation below CF, contrasting with a larger, longer-duration area of suppression above CF. As seen in the accompanying graph, the CRA accurately estimated the direction (up) and rate (slowest) of FM sweeps that elicited the best response. Moreover, while the downsweep prediction was not within one SEM of the actual FM response, the CRA consistently predicted lower responses to downsweeps than to upsweeps.

In the unit shown in Fig. 5(c), the predictions closely matched both the shape and the magnitude the actual responses for upward FM sweeps for all but the 8 ms (1.5 kHz/ms) sweep. The CRA revealed a large area of suppression in the spectral regions at and above the CF, which was strongest at short conditioner-probe intervals (<8 ms). Just below CF there was a spectrally narrow band of facilitation that extended backward along the time axis, abruptly widening along the frequency axis at intervals beyond 24 ms. This spectrotemporal asymmetry predicted suppression by rapid downsweeps, and facilitation by a broad range of upsweeps that grew with sweep duration. As seen on the right, the upsweep prediction closely approximated both the shape and magnitude of the rate-function for upsweeps, whereas the predicted rate function for down-sweeps matched the shape, but grossly underestimated the magnitude, of actual responses to downsweeps.

Fig. 5(d) shows a rate-dependent unit with a particularly complex FM response. In rate-dependent units, directional selectivity shifts from up- to down-preferring, depending on the modulation rate. This particular unit responded best to either fast upsweeps or slow downsweeps depending on the sweep rate. The reversal in directional preference occurred between 0.75 and 1.5 kHz/ms sweep rates. The CRA is dominated by a particularly strong and persistent “on-CF” suppression, flanked on the high-frequency side by a temporally and spectrally circumscribed region of inhibition from 0 to 8 ms before the probe. This asymmetric pattern suggests a preference for slow downsweeps (due to the short-delay inhibition) and fast upsweeps (due to fact that slow upsweeps remain in the on-CF suppressive area longer). Indeed, the CRA correctly predicted the rate-dependent reversal in directionality, but underestimated by one-half the FM rate at which the reversal would occur (∼0.6 predicted vs. ∼1.2 kHz/ms actual). Units like this one that reverse directional preference are ideal candidates for encoding of certain mustached bat communication sounds containing upward and downward FM components with alternating fast and slow modulation rates.

Fig. 6 shows units whose CRAs yielded poor predictions. The CRA in Fig. 6(a) was clearly asymmetric, marked by a very strong high-side suppression that would select particularly against rapid downward sweeps, and conversely, a long-duration, low-side facilitation that would enhance response to upward sweeps. However, the only feature successfully predicted was preference for slow sweeps. The actual FM response was non-directional, the response growing with sweep duration regardless of sweep direction. For the unit shown in Fig. 6(b), the CRA correctly predicted a growing preference for faster sweeps, as well as the rate that evoked maximal response. However, the CRA was predominantly suppressive over the entire sampled spectrotemporal space and thereby predicted no directionality, whereas the actual response was strongly selective for upsweeps. The asymmetrical CRA in Fig. 6(c) was quite successful predicting overall (upward) directional preference, but incorrectly estimated the maximal response. This unit displays classic on-CF suppression, as the region in the standard response area (left) matches spectrally the temporally circumscribed inhibitory region in the CRA. Finally, Fig. 6(d) is an example of a unit with a clearly defined long-duration region of facilitation above the CF, a weaker region of facilitation below, and a brief, short-delay, broadly tuned region of suppression centered at CF. This pattern predicted a strong response for long-duration sweeps in either direction, and an increase in down-selectivity with an increase in sweep duration. However, the unit strongly preferred upsweeps of intermediate duration.

Fig. 6.

Selected examples of CRAs that were unsuccessful predicting actual FM sweep results. (a) The CRA from this unit, showing a strong suppressive region above CF, vastly overestimated the response to upsweeping FM at all rates save the slowest two. As a result, the predicted FM response profile (right) was directional, but the cell was non-directional. The overall preference for slower FM rates, however, was correctly predicted. (b) CRA with a broadly tuned, symmetrical inhibitory area around the CF. The cell clearly preferred upsweeping FM, and yet the CRA predicted no directionality. However, the CRA correctly predicted the rate at which the response to upsweeps was maximal. (c) CRA with strong, focal band of suppression just above CF, and diffuse and weak facilitation below. The CRA predicted significant preference for upsweeping FM at all rates (right). While the prediction of overall directionality was correct, the CRA incorrectly estimated the rate of upward FM that evoked the maximal response. (d) A CRA with narrow, long-duration suppressive area that broadened significantly in temporal proximity to the CF probe, bounded by broad regions of facilitation above and below CF. The prediction from this CRA (right) was incorrect in multiple dimensions. The CRA predicted selectivity for downsweeping FM at the slowest rates tested, but the unit had little down FM response and was highly selective for up FM within a narrow range of FM rates.

3.7. Specific prediction accuracy

Independently for each sweep direction and rate of FM, CRA prediction accuracy was assessed relative to the standard error of the mean (SEM) of the actual FM sweep responses. The CRA-generated predictions were considered accurate if the predicted spike counts for each sweep direction were within one SEM for at least 4 of the 5 rates of FM used for comparison. By our criteria, CRAs were successful predicting response selectivity for 12-kHz bandwidth preferred-direction sweeps in 20.6% of the units, whereas for null-direction sweeps prediction accuracy fell to only 14.7% of the units. The results for 6 kHz sweep predictions were slightly better for preferred-direction sweeps (23.5%), and better for null-direction sweeps (23.5%).

3.8. Overall prediction accuracy

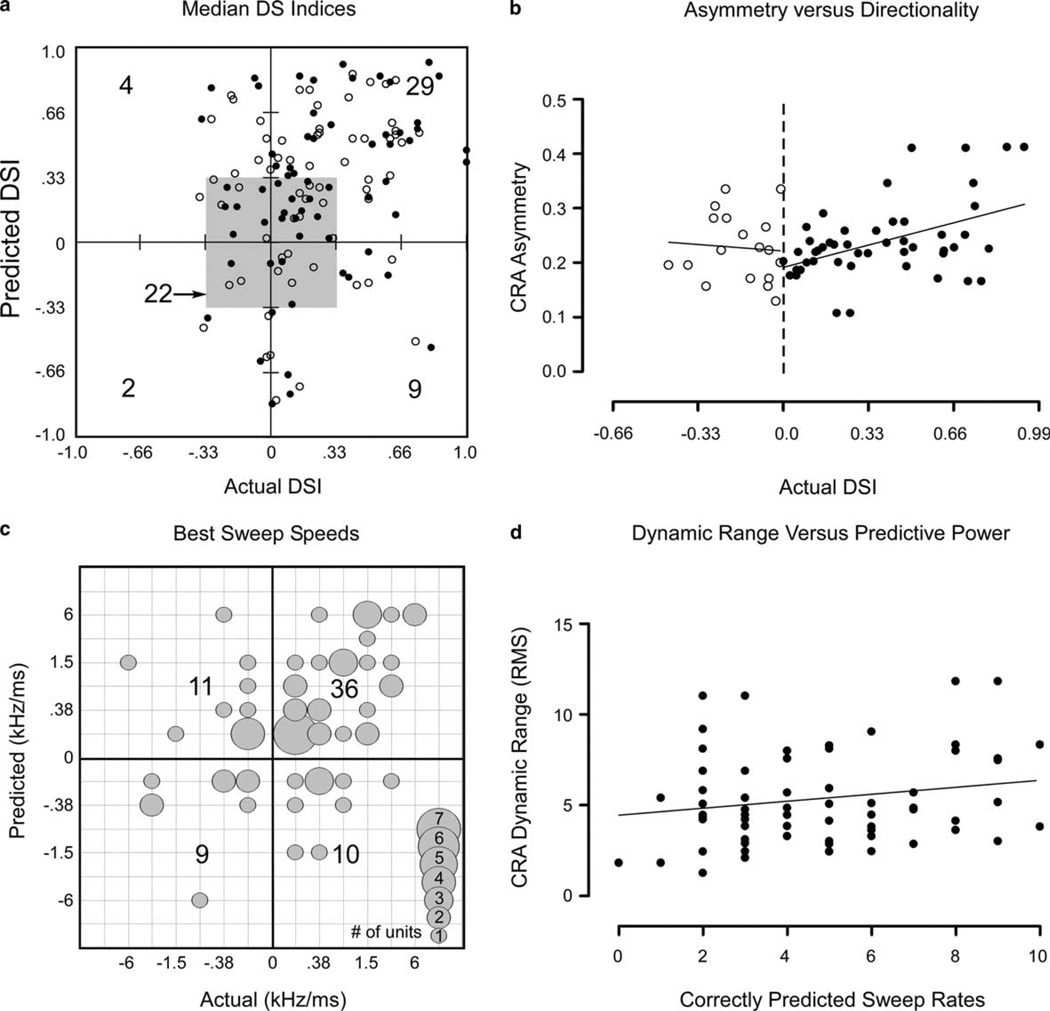

Summary plots comparing CRA predictions to actual FM sweep results are shown in Fig. 7. A comparison of predicted vs. actual directionality (expressed as the DS index) is shown in Fig. 7(a). If all CRA predictions of directionality were correct, the data points would distribute along the diagonal line bisecting the lower left (i.e., down-preferring) and upper right (up-preferring) quadrants in the plot. The majority of data points fell in the up-selective portion of the upper right quadrant (n = 29) and in the non-directional center (n = 22), indicating that predicted and actual data agreed at least at a descriptive level. However, for the few cells that showed stronger responses to downward sweeps (negative DS index), there was a very poor correlation between actual and predicted values.

Fig. 7.

Summaries of prediction accuracy. (a) Scatter plot comparing DS indices calculated from actual and predicted FM responses. Positive and negative DS indices indicate selectivity for up- and downsweeping FM, respectively. Central square indicates directional selectivity significance limit of 0.333 DS index. Results for both FM bandwidths are shown (open circles: 6 kHz; closed circles: 12 kHz). Gross details indicate that predicted and actual results agree for the bulk of units indicating a general preference for upsweeping FM or non-directionality. Counts shown are bandwidth/ units; the greatest counts were found in the non-directional (22) and up-selective (29) categories. A significant correlation was observed (parametric Pearson r = 0.27, p < 0.05) between predicted and actual median DS indices. (b) Scatterplot comparing CRA asymmetry (absolute values) with actual DS indices. Upward directional selectivity (filled circles) was correlated with the degree of CRA asymmetry (r = 0.46, p < 0.05), however, downward DS index (open circles) was not (r = −0.08, p = 0.77). (c) Bubble plot comparing actual and predicted best sweep speeds. Downward sweeps are indicated by negative sweep speeds. Many units fell close to the diagonal, indicating agreement between actual and predicted results. Most units preferred slow upsweeping FM. A significant correlation was observed between predicted and actual best sweep speeds. (d) Scatterplot comparing dynamic range to prediction accuracy. The dynamic range of CRAs as measured by the RMS method was not correlated with the number of correctly predicted sweep rates (r = 0.19, p = 0.12).

The degree of asymmetry around the CF for a given CRA may be related to the overall FM directionality of the cell. The asymmetry for each CRA was judged by subtracting cell-by-cell the top half of the CRA from the inverted lower half (equivalent to folding the CRA in half about the CF and subtracting the two halves from one another), and summing the absolute values of the resultant difference matrix. Asymmetry was plotted as a function of actual DS index in Fig. 7(b). A significant correlation was found for upsweeping FM (r = 0.46, p < 0.05), but not for downsweeping FM (r = −0.08, p = 0.77).

With regard to predictions of sweep rate preference (Fig. 7(c)), we found a similar level of agreement. The bulk of the population preferred slow, upsweeping FM, and the predictions bear this out to a certain degree. A significant correlation was observed between predicted and actual best sweep speeds (non-parametric Spearman r = 0.43, p < 0.01). There was a weak correlation between absolute values of predicted and actual best sweep speeds (non-parametric Spearman r = 0.38, p < 0.01). However, there was a large number of cases where the sign (direction) of the predicted best speed was opposite the actual best sweep speed, reflecting the mistakes in predicting directionality shown in Fig. 7(a).

Finally, we compared CRA dynamic range (as measured by the root mean square method) with prediction accuracy to address the possibility that the amount of variation in a given CRA may influence its ability to generate predictions with the distinct selectivity patterns seen in actual FM responses. However, as seen in Fig. 7(d), the dynamic range of the CRAs does not vary as a function of the number of correctly predicted rates.

4. Discussion

The main purpose of this study was to determine quantitatively whether rate-dependent directional selectivity for linear FM sweeps could be predicted from two-tone interactions in time and frequency. Traditionally, two-tone masking paradigms (simultaneous and non-simultaneous) have been used to reveal inhibitory response areas in neurons with little or no spontaneous discharge rate. Inhibitory domains were revealed by varying masker amplitude and frequency, and noting the effect on the response to a CF probe fixed at a level just above threshold. The temporal relationship of masker and probe in many of these studies was not varied. The receptive field was then constructed by plotting the inhibitory area together with the excitatory area (usually obtained from the masker-alone response) as an iso-rate curve in coordinates of level vs. frequency. By examination of the receptive field, responses to FM signals were qualitatively predicted based upon the trajectory of the sweeps with respect to inhibitory domains.

However, amplitude spectra of FM sweeps vary in a time-dependent fashion. It is legitimate to ask whether receptive fields obtained at a fixed masker–probe time interval could adequately account for responses to such dynamic stimuli. This problem is particularly important with regard to predicting responses to sweeps with different modulation rates (“velocity”). Previous studies have been limited to establishing a qualitative correlation between the strength, shape, and spectral location of inhibitory sidebands and responses to FM sweeps (Heil et al., 1992b; Shannon-Hartman et al., 1992; Suga, 1965a); none have attempted to link receptive field features to FM responses quantitatively. By modifying the two-tone paradigm to assess the receptive field properties along frequency vs. time dimensions, we sought to reveal how the receptive field varies in time.

Furthermore, those authors who have attempted to relate two-tone interactions to FM directionality have typically called attention only to inhibitory interactions between successive frequencies in an FM sweep (Gordon and O’Neill, 1998; Heil et al., 1992b; Shannon-Hartman et al., 1992; Suga, 1965a). However, a growing number of two-tone studies have uncovered rich facilitatory interactions that are dependent on either the spectral or temporal relationship between ‘masker’ and probe (Leroy and Wenstrup, 2000; Mittmann and Wenstrup, 1995; Olsen and Suga, 1991; Brosch and Schreiner, 1997, 2000; Brosch et al., 1999). The facilitatory interactions described in these studies exert their maximal effect when probe and masker are widely separated in frequency, typically when the tones are related harmonically. In our study, we examined fine-grain spectrotemporal masking patterns in a very narrow band (∼0.2 octave) and temporal window (32 ms) around CF. This method revealed powerful inhibitory and facilitatory interactions sensitive to subtle changes in both the temporal and spectral domains. We examined the degree to which these interactions could be used to predict responses to FM sweeps over a wide range of biologically relevant modulation rates. We found that two-tone interactions are insufficient to describe normalized FM rate profiles in a majority of units.

4.1. Models of FM rate and directional selectivity

Up- or down-sweeping fixed bandwidth sweeps centered at the same frequency have identical long-term spectral content, but the frequencies occur in opposite temporal order. For a single neuron to prefer a particular FM direction at a particular sweep rate, it must be able to compare spectral information at more than one time point in a time-dependent manner. At the level of the single neuron, comparisons between frequencies at multiple time points are possible when the responses to inputs with different characteristic frequencies are temporally offset from one another. There are two major classes of small-network models for FM directionality and rate selectivity. The relative timing of different inputs to the target cell is critical in both model classes.

4.1.1. Sideband inhibition model

A number of studies (including this one) have implicated input from an “asymmetrical” inhibitory area (i.e., a single sideband) in the creation of FM directional selectivity. This model is functionally similar to a model of directional selectivity for visual motion discussed by Ruff et al. (1987), but was proposed conceptually much earlier to explain FM directionality in the bat auditory system by Suga (1965a) and Suga and Schlegel (1973). In its most parsimonious form, the sideband inhibition model proposes that a directionally selective neuron receives two inputs, one excitatory and the other inhibitory. The best frequencies of these opposing inputs are typically thought of as different, but this is not required: an inhibitory sideband could be created by any asymmetry in the shape of the response areas of the two inputs. The principle behind the response of this circuit to an FM sweep is simple: sweeps in the preferred direction will elicit more spikes because they stimulate the excitatory area before the inhibitory sideband. By contrast, sweeps in the null-direction elicit fewer spikes, because they activate the inhibitory sideband before the excitatory area, resulting in suppression (akin to forward masking; Fuzessery, 1994; Heil et al., 1992a; Shannon-Hartman et al., 1992; Suga, 1965b; Suga and Schlegel, 1973; Suga et al., 1974).

Asymmetrical sideband inhibition of this type has been documented in the IC of a number of mammals, including bat (Casseday and Covey, 1992; Fuzessery, 1994; Fuzessery and Hall, 1996; Gordon and O’Neill, 1998), cat (Ehret and Merzenich, 1988; Erulkar et al., 1968), ferret (Kowalski et al., 1995), rat (Zhang et al., 2003), and chinchilla (Nuding et al., 1999), although with the exception of Fuzessery and colleagues, these studies did not investigate the relationship between inhibitory sidebands and FM directionality. Many CRAs obtained in the present study provide evidence of spectrally and temporally defined regions of inhibition that would be consistent with the sideband inhibition model. Good examples are shown in Figs. 2(c), 5(c) and (d), and 6(a) and (c), all of which have well-defined asymmetrical regions of two-tone suppression that are consistent with sideband inhibition. However, the failure of these two-tone CRAs to predict directional selectivity in a number of these same cases brings to question whether a simple sideband inhibition model can account for all the nuances of rate and directional selectivity. Our study is not the first to point out this inadequacy. In his classic review, Suga (1973) described “paradoxically asymmetric units” that have asymmetrical sideband inhibition (determined with two-tone techniques) without accompanying directional selectivity for FM sweeps. It may be that the sideband inhibition model is too simplistic to account for FM directionality in the IC.

4.1.2. Serial excitation model

A second major class of model is based on temporally offset, sub-threshold excitatory inputs that are anatomically ordered by CF along a dendrite. The orderly arrangement of inputs establishes a directional preference for spatio-temporal summation along the dendrite. An FM sweep that stimulates the inputs in a sequence towards the soma results in summation, whereas stimulation in sequence away from the soma does not. This model has been proposed by several researchers as a potential method of encoding FM (Erulkar et al., 1968; Fuzessery and Hall, 1996; Heil et al., 1992b; Poon et al., 1992) and is based on a model proposed for visual motion discrimination (Rall, 1964; Segev and Rall, 1998).

We found evidence for delay-tuned facilitatory regions of the kind predicted by the serial excitation model (examples Figs. 5(b) and 6(c)). The finding that facilitatory subfields in CRAs tended to be of longer duration than inhibitory subfields also corresponds well to the nature of the inputs in the model, as the cable properties of dendrites tend to delay and smear voltages in time (Segev, 1992). Direct testing of this model with pairs of tones is problematic in extracellular recordings, as one of its primary assumptions is that individual synaptic inputs are sub-threshold. However, a unit that had a specific neural implementation of the serial excitation model might be expected to produce CRAs with facilitatory subfields that are spectrotemporally tilted, examples of which were rare and largely unconvincing (Fig. 5(b)).

4.2. CRA prediction accuracy

Two-tone CRAs reveal the modulatory effects that presence of one tone (the ‘conditioner’) has on the response to another (the ‘probe’) as a function of the temporal and frequency separation of the two tones. By multiplying CRAs with FM sweeps, we attempted to predict certain key response features of IC units, including preference for FM rate and, in particular, direction. In general, the gross features of directionality and rate preference were similar between CRA predictions and actual FM sweep responses (Fig. 7(a) and (c)). Also, the overall asymmetry of CRAs was significantly correlated with FM directionality (Fig. 7(b)). However, predictions were quantitatively accurate in only 20% of the sampled population. The low rate of success predicting response to sweeps argues that the simplest of FM models, the two-input sideband inhibition model, cannot fully account for all forms of FM sweep selectivity in the IC.

4.3. Factors degrading CRA prediction accuracy

Various factors could account for the low rate of success predicting FM directionality. First, it is certainly true that two-tone stimuli used to obtain the CRA lack the spectral complexity of FM sweeps, and therefore may fail to activate potentially rich interactions among responses to frequencies within the sweep. The two-tone stimulus is after all an abstract simulation of spectral motion, akin to the way two tones separated in time and space can simulate sound source motion. The sparseness of the two-tone stimulus may not adequately recreate the excitation pattern and non-linear interactions produced by a continuous FM sweep. Adding additional tones along the sweep trajectory to make the conditioning stimulus more like an FM sweep might be expected to improve predictability, but the number of additional tones that can be added is limited by the difficulty of packing such brief tones into the stimulus without overlap or spectral artifact.

Second is the problem of noise in the CRA. In some units, spike counts were low because the response to the brief (4 ms) tones used to generate the CRAs was poor. Responses to longer tones, while typically low in magnitude (often averaging 1 spike per presentation), were often much more reliable than responses to shorter tones. Consequently, the integrity of some CRAs and their corresponding predictions could be compromised by momentary and unpredictable fluctuations in background activity level. Smoothing of the CRAs limited the effect of these fluctuations to some degree, but had the unfortunate side-effect of reducing the contrast between facilitation and suppression in the CRA.

The third factor diminishing the predictive power of the technique was incomplete sampling of the CRA. Frequencies occurring in the sweep following the instantaneous occurrence of the CF might also modulate the response to the first half of the sweep (a form of backward masking). Recordings in the IC of the big brown bat have shown that the onset of inhibition often precedes that of excitation (Covey et al., 1996; Faure et al., 2003). In future experiments, the onset of the conditioning tone ought to be extended past a Δt of 0 (simultaneous masking) to account for the possibility of shorter latency inhibition.

5. Conclusions

For 20% of IC units, the CRA was successful predicting the response to FM. For these units, we suggest that selectivity for rate and direction of FM is related to the way in which preceding frequencies in an FM sweep suppress and/or facilitate the CF response. However, for the majority of units, the two-tone stimulus used in this study revealed spectrotemporally dependent modulation, but was not successful at generating quantitatively accurate predictions of FM response. Frequencies occurring in an FM sweep prior to the CF presumably activate frequency-selective inputs in specific temporal sequences, similar to the way our two-tone stimulus activates such inputs, but these inputs do not appear to operate independently from one another. In the IC, a given facilitatory or inhibitory input’s efficacy may itself be influenced by interactions between frequencies present in a complex signal. Future studies must examine what differences exist between units whose CRAs yield accurate predictions and those units whose CRAs yield poor predictions. Also, it will be crucial to determine to what extent noise and input non-linearity contribute to the quality of predictions and to FM response properties themselves. Despite the failure of predictions in the majority of units, we maintain that the relative timing of the inputs to a cell must be critical for determining rate and directional selectivity for FM. However, results seem to indicate that classic FM models may be insufficient for describing the complexity of FM responses at the level of the inferior colliculus. An understanding of the interactions between inputs to the IC will be required for a detailed picture of the spectral and temporal properties that underlie responses to complex, time varying acoustic signals.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute for Deafness and Communicative Disorders (NIDCD R01-DC03717) and from a National Institute of Mental Health Training Grant (5 T32 MH19942-07). We thank John Housel for technical assistance, animal care, and assistance with experiments; Robert Emerson and William Vaughn for statistical advice; and Scott Seidman and Garrett Johnson for advice regarding the computation of predictions.

Abbreviations

- CF

characteristic frequency

- CRA

conditioned response area

- DS

directional selectivity

- DSI

directional selectivity index

- EFi

instantaneous effective frequency

- FM

frequency modulation

- FSL

first spike latency

- IC

inferior colliculus

- ICc

central nucleus of the inferior colliculus

- ICXv

ventral division of the external nucleus of the inferior colliculus

- NB

narrow band

- SEM

standard error of the mean

- STRF

spectrotemporal receptive field

References

- Bodenhamer R, Pollak GD, Marsh DS. Coding of fine frequency information by echoranging neurons in the inferior colliculus of the Mexican free-tailed bat. Brain Res. 1979;171:530–535. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)91057-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand A, Urban R, Grothe B. Duration tuning in the mouse auditory midbrain. J. Neurophysiol. 2000;84:1790–1799. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.4.1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britt R, Starr A. Synaptic events and discharge patterns of cochlear nucleus cells. II. Frequency modulated tones. J. Neurophysiol. 1976;39:179–194. doi: 10.1152/jn.1976.39.1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosch M, Schreiner CE. Time course of forward masking tuning curves in cat primary auditory cortex. J. Neurophysiol. 1997;77:923–943. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.2.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosch M, Schreiner CE. Sequence sensitivity of neurons in cat primary auditory cortex. Cereb. Cortex. 2000;10:1155–1167. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.12.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosch M, Schulz A, Scheich H. Processing of sound sequences in macaque auditory cortex: response enhancement. J. Neurophysiol. 1999;82:1542–1559. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.3.1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casseday JH, Covey E. Frequency tuning properties of neurons in the inferior colliculus of an FM bat. J. Comp. Neurol. 1992;319:34–50. doi: 10.1002/cne.903190106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casseday JH, Ehrlich D, Covey E. Neural tuning for sound duration: role of inhibitory mechanisms in the inferior colliculus. Science. 1994;264:847–850. doi: 10.1126/science.8171341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covey E, Kauer JA, Casseday JH. Whole cell patch-clamp recording reveals subthreshold sound-evoked postsynaptic currents in the inferior colliculus of awake bats. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:3009–3018. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-09-03009.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KA, Gdowski GT, Voigt HF. A statistically based method to generate response maps objectively. J. Neurosci. Meth. 1995;57:107–118. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(94)00146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehret G, Merzenich MM. Complex sound analysis (frequency resolution, filtering and spectral integration) by single units of the inferior colliculus of the cat. Brain Res. Rev. 1988;13:139–163. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(88)90018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erulkar LD, Butler RA, Gerstein GL. Excitation and inhibition in cochlear nucleus. II Frequency-modulated tones. J. Neurophysiol. 1968;31:537–548. doi: 10.1152/jn.1968.31.4.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faure PA, Fremouw T, Casseday JH, Covey E. Temporal masking reveals properties of sound-evoked inhibition in duration-tuned neurons of the inferior colliculus. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:3052–3065. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-07-03052.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuzessery ZM. Response selectivity for multiple dimensions of frequency sweeps in the pallid bat inferior colliculus. J. Neurophysiol. 1994;72:1061–1079. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.3.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuzessery ZM, Hall JC. Role of GABA in shaping frequency tuning and creating FM sweep selectivity in the inferior colliculus. J. Neurophysiol. 1996;76:1059–1073. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.2.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon M, O’Neill WE. Temporal processing across frequency channels by FM selective auditory neurons can account for FM rate selectivity. Hear. Res. 1998;122:97–108. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(98)00087-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon M, O’Neill WE. An extralemniscal component of the mustached bat inferior colliculus selective for direction and rate of linear frequency modulations. J. Comp. Neurol. 2000;426:165–181. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20001016)426:2<165::aid-cne1>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heil P. Aspects of temporal processing of FM stimuli in primary auditory cortex. Acta Otolaryngol. Suppl. 1997;532:99–102. doi: 10.3109/00016489709126152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heil P, Irvine DR. Functional specialization in auditory cortex: responses to frequency-modulated stimuli in the cat’s posterior auditory field. J. Neurophysiol. 1998;79:3041–3059. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.6.3041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heil P, Rajan R, Irvine DRF. Sensitivity of neurons in cat primary auditory cortex to tones and frequency-modulated stimuli. II: Organization of response properties along the “isofrequency” dimension. Hear. Res. 1992a;63:135–156. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(92)90081-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heil P, Langner G, Scheich H. Processing of frequency-modulated stimuli in the chick auditory cortex analogue: evidence for topographic representations and possible mechanisms of rate and directional selectivity. J. Comp. Physiol. (A) 1992b;171:583–600. doi: 10.1007/BF00194107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanwal JS, Matsumura S, Ohlemiller K, Suga N. Analysis of acoustic elements and syntax in communication sounds emitted by mustached bats. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1994;96:1229–1254. doi: 10.1121/1.410273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski N, Versnel H, Shamma SA. Comparison of responses in the anterior and primary auditory fields of the ferret cortex. J. Neurophysiol. 1995;73:1513–1523. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.4.1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leroy SA, Wenstrup JJ. Spectral integration in the inferior colliculus of the mustached bat. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:8533–8541. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-22-08533.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson JR, Cynader MS. Sensitivity of cat primary auditory cortex (A1) neurons to the direction and rate of frequency modulation. Brain Res. 1985;327:331–335. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91530-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittmann DH, Wenstrup JJ. Combination-sensitive neurons in the inferior colliculus. Hear. Res. 1995;90:185–191. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(95)00164-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuding SC, Chen GD, Sinex DG. Monaural response properties of single neurons in the chinchilla inferior colliculus. Hear. Res. 1999;131:89–106. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(99)00023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen JF, Suga N. Combination-sensitive neurons in the medial geniculate body of the mustached bat: encoding of relative velocity information. J. Neurophysiol. 1991;65:1254–1274. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.65.6.1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill WE. Responses to pure tones and linear FM components of the CF-FM biosonar signal by single units in the inferior colliculus of the mustached bat. J. Comp. Physiol. [A] 1985;157:797–815. doi: 10.1007/BF01350077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill WE, Brimijoin WO. Directional Selectivity for FM sweeps in the suprageniculate nucleus of the mustached bat medial geniculate body. J. Neurophysiol. 2002;88:172–187. doi: 10.1152/jn.00966.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill WE, Housel J, Brimijoin WO. The effect of FM bandwidth on modulation rate selectivity in the external nucleus of the bat IC (ICX) Association for Research in Otolaryngology Abstracts. 2003:26. [Google Scholar]

- Poon PW, Chen X, Cheung YM. Differences in FM response correlate with morphology of neurons in the rat inferior colliculus. Exp. Brain Res. 1992;91:94–104. doi: 10.1007/BF00230017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rall WA. Theoretical significance of dendritic trees for neuronal input–output relations. In: Reiss RF, editor. Neural Theory Modelling. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1964. pp. 73–97. [Google Scholar]

- Ruff PI, Rauschecker JP, Palm G. A model of direction-selective “simple” cells in the visual cortex based on inhibition asymmetry. Biol. Cybern. 1987;57:147–157. doi: 10.1007/BF00364147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuller G, Radtke-Schuller S, Betz M. A stereotaxic method for small animals using experimentally determined reference profiles. J. Neurosci. Meth. 1986;18:339–350. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(86)90022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segev I. Single neurone models: oversimple, complex and reduced. Trends Neurosci. 1992;15:414–421. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(92)90003-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segev I, Rall W. Excitable dendrites and spines: earlier theoretical insights elucidate recent direct observations. Trends Neurosci. 1998;21:453–460. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01327-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon-Hartman S, Wong D, Maekawa M. Processing of pure-tone and FM stimuli in the auditory cortex of the FM bat, Myotis lucifugus . Hear. Res. 1992;61:179–188. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(92)90049-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suga N. Analysis of frequency-modulated sounds by auditory neurons of echo-locating bats. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 1965a;179:26–53. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1965.sp007648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suga N. Functional properties of auditory neurons in the cortex of echo-locating bats. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 1965b;181:671–700. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1965.sp007791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suga N. Feature extraction in the auditory system of bats. In: Møller ARR, editor. Basic Mechanisms in Hearing. New York, London: Academic Press; 1973. pp. 675–744. [Google Scholar]

- Suga N, Schlegel P. Coding and processing in the auditory systems of FM-signal-producing bats. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1973;54:174–190. doi: 10.1121/1.1913561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suga N, Simmons JA, Shimozawa T. Neurophysiological studies on echolocation systems in awake bats producing CF-FM orientation sounds. J. Exp. Biol. 1974;61:379–399. doi: 10.1242/jeb.61.2.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian B, Rauschecker JP. Processing of frequency-modulated sounds in the cat’s anterior auditory field. J. Neurophysiol. 1994;71:1959–1975. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.5.1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian B, Rauschecker JP. Processing of frequency-modulated sounds in the cat’s posterior auditory field. J. Neurophysiol. 1998;79:2629–2642. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.5.2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang LI, Tan AY, Schreiner CE, Merzenich MM. Topography and synaptic shaping of direction selectivity in primary auditory cortex. Nature. 2003;424:201–205. doi: 10.1038/nature01796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]