Abstract

Objective

Program planners work with promotoras (the Spanish term for female community health workers) to reduce health disparities among underserved populations. Based on the Role-Outcomes Linkage Evaluation Model for Community Health Workers (ROLES) conceptual model, we explored how program planners conceptualized the promotora role and the approaches and strategies they used to recruit, select, and sustain promotoras.

Design

We conducted semi-structured, in-depth interviews with a purposive convenience sample of 24 program planners, program coordinators, promotora recruiters, research principal investigators, and other individuals who worked closely with promotoras on United States-based health programs for Hispanic women (ages 18 and older).

Results

Planners conceptualized the promotora role based on their personal experiences and their understanding of the underlying philosophical tenets of the promotora approach. Recruitment and selection methods reflected planners’ conceptualizations and experiences of promotoras as paid staff or volunteers. Participants described a variety of program planning and implementation methods. They focused on sustainability of the programs, the intended health behavior changes or activities, and the individual promotoras.

Conclusion

To strengthen health programs employing the promotora delivery model, job descriptions should delineate role expectations and boundaries and better guide promotora evaluations. We suggest including additional components such as information on funding sources, program type and delivery, and sustainability outcomes to enhance the ROLES conceptual model. The expanded model can be used to guide program planners in the planning, implementing, and evaluating of promotora health programs.

Introduction

There is increasing global consensus that social, economic, and environmental conditions contribute to health status, and inequitable distribution of these conditions significantly contribute to persistent and pervasive health disparities between and across populations (Braveman 2006; Commission on the Social Determinants of Health 2008). In the United States (U.S.), racial/ethnic disparities between Whites and Hispanics range from obesity and diabetes to tooth decay (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2011). Language barriers, restricted access to care due to lack of health insurance, limited understanding of how to navigate the complex and fragmented healthcare system, and lack of culturally appropriate care contribute to health disparities among Hispanics, the largest U.S. ethnic minority population (Marshall et al. 2005). Recent xenophobic legislation aimed at undocumented immigrants has heightened fear of authorities and further restricted the ability of many Hispanic immigrants and their families to access health and social services (Gee and Ford 2011). Due in part to the growing shortage of community-based healthcare providers and the challenges of reaching populations marginalized by language, culture, lack of health insurance, geography, immigration status, and other structural barriers, health program planners from various institutions (e.g. community organizations, academia) have selected to train community health workers (CHWs) to deliver health education and outreach services to underserved populations, particularly racial/ethnic minority groups. (Andrews et al. 2004, Ingram et al. 2008, Aiken et al. 2009).

In the Alma Ata Declaration, the World Health Organization (WHO 1978) acknowledged the value and utility of CHWs as a resource for the delivery of primary healthcare services and implementation of peer-to-peer social learning approaches internationally. The WHO (1989) definition of CHWs is still widely accepted:

Community health workers should be members of the communities where they work, should be selected by the communities, should be answerable to the communities for their activities, should be supported by the health system but not necessarily a part of its organization, and have shorter training than professional workers (p. 6).

A generic umbrella term referring to a wide variety of paraprofessional health workers in diverse settings and healthcare systems across the globe, CHWs are known by in Spanish as promotoras1 (Lehman & Sanders 2007).

Social networks and community empowerment are two key constructs that inform the CHW delivery model. This model is predicated on enlisting, training, and empowering a community’s recognized natural leaders to provide health education and link other community members to existing health services, with the goal of improving and maintaining healthy behaviors (Israel, 1985, Bishop et al. 2002). Thus, this healthcare delivery model contributes to community empowerment by building community capacity to plan, organize, and deliver healthcare (Zimmerman 2000).

Depending on the philosophical underpinnings and the community contexts and settings, CHWs perform different types of activities and function at different levels within health programs and systems (Crigler et al. 2009). In the U.S., CHW programs tend to focus on a specific health issue. Funded through short-term external grants, these programs are often coordinated through community-based organizations, coalitions, faith-based organizations, hospitals, healthcare clinics, or academic institutions (HRSA, 2009). In some programs CHWs volunteer their time but may receive monetary reimbursement for certain activities. In others they function as salaried employees. However, the lack of national recognition of the CHW role as a position reimbursable through federal funding mechanisms compromises the sustainability of CHW positions.

Definitions of CHW roles tend to be general and often limited to brief mentions of CHW relationships with community members and to their roles in linking the community with healthcare resources (Rhodes et al. 2007). Examples of CHW role descriptors include being natural helpers, community leaders, and individuals to whom others naturally turn to for information and resources (Bishop et al. 2002). Within the contexts of individual programs and across the healthcare system, the lack of clear definitions or delineations of CHWs’ roles may contribute to blurred role boundaries and to potential conflicts in role expectations and position-related parameters (Ashforth et al. 2000, Brownstein et al. 2005). Role boundaries aid in identifying specific tasks and expectations and provide the individual practitioner with a sense of understanding or control within a specific position (Zerubavel 1991). Identified gaps in the CHW research literature include a lack of attention to CHW role conceptualization and the lack of detailed information about CHW recruitment processes (Jackson and Parks 1997, Rhodes et al. 2007). O’Brien and colleagues (2009) conducted a systematic review on CHW recruitment, selection, and training, focusing on how selection and training influenced CHW role development. However, they did not examine how CHW role conceptualization influenced the selection process.

There is increasing use of promotoras to implement grant-funded community-based programs with the aim of preventing or controlling obesity (Kim et al. 2004, Balcazar et al. 2006, Keller and Cantue 2008, Baquero et al. 2009) among U.S. Hispanic women, a group with one of the highest risks for developing obesity-related diseases such as Type II diabetes and hypertension (Cossrow and Falkner 2004). In these programs, program planners employ promotoras as a key way to deliver culturally and linguistically competent interventions; however, the conceptualizations and expectations of promotoras often differ across such programs. The goals of this study were to further understand how program planners’ promotora role conceptualizations influenced 1) the planning process and placement of promotoras within the wider healthcare spectrum; 2) the establishment of promotora role boundaries and the type and amount of work they perform; and 3) outcome expectations of promotora-delivered health programs (Gilson et al. 1989, Zerubavel 1991, Ashforth et al. 2000, Andrews et al. 2004). We based this research on the premise that planners’ beliefs, conceptualizations, and expectations of the promotora role drive health program components and processes from development through implementation and that the expected role influences the criteria and measures program planners use to evaluate the effectiveness of promotora-delivered interventions. Better understanding of how program planners conceptualize and implement promotora-delivered health interventions can provide an evidence base for improved utilization of promotoras in community health programs. Although this research focused on promotora-delivered interventions related to obesity, the findings are applicable to promotora-delivered interventions focused on diverse health issues (e.g., asthma, cancer, diabetes).

Purpose and Conceptual Model

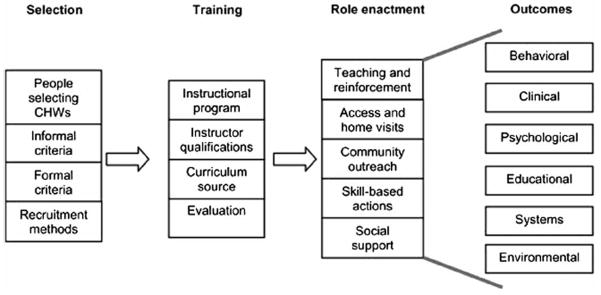

Employing a qualitative descriptive research design we sought to explore how planners conceptualized and implemented the role of promotoras within obesity prevention, physical activity, and/or nutrition programs designed specifically for U.S. Hispanic women. We used the Role-Outcomes Linkage Evaluation Model for Community Health Workers (ROLES) model (Figure 1; O’Brien et al. 2009), one of the most recent models which illustrates how CHWs are first selected and later linked to program outcomes, to construct our in-depth interview guide for the study. We intended to modify the model if study results revealed disparities between the current model and program planners’ perspectives of promotoras’ roles.

Figure 1.

O’Brien el al.’s (2009) Role-Outcomes Linkage Evaluation Model for Community Health Workers.

Reprinted from American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 37/6S. O’Brien MJ. Squires AP, Bixby RA. Larson SC; Role development of community health workers. S262–269. Copyright (2009), with permission from Elsevier.

The ROLES model describes a sequential process in which program planners (1) select and (2) train CHWs, who then (3) enact the role through teaching, home visits, community outreach, skill-based actions, and social support. The final step involves the (4) examination of outcomes and effectiveness measured by changes in behavioral, clinical, psychological, educational, systemic, and environmental health-related indicators (O’Brien et al. 2009). For this research we focused on program planners’ perspectives and experiences, rather than promotoras, given planners’ responsibilities for creating and managing health programs; organizing promotora activities; and recruiting, selecting, and training promotoras (Lehman & Sanders, 2007). The University of South Carolina Institutional Review Board approved the research.

Methods

Participant Recruitment, Interview Guide Development, and Data Collection

We recruited a purposive convenience sample of program planners, program coordinators, promotora recruiters, researchers, and other individuals working closely with promotoras. Inclusion criteria were: 1) the promotora program included a focus on obesity prevention, physical activity, and/or nutrition given the high rates of obesity among Hispanic women (Ogden et al. 2012); 2) the program was U.S.-based and served primarily Hispanic women (ages 18 and older), although programs may have included family members; and 3) the program planner spoke English. We identified names of potential participants through literature searches, Internet searches of evidence-based promotora programs for Hispanic women, and referrals from other program planners. We made initial telephone and/or e-mail contact with 65 individuals, of whom 25 (38%) did not respond. Among the 40 responders, 14 (22%) reported that they did not work on a project that met the inclusion criteria; 2 (3%) declined to participate due to time constraints; and 24 (37%) agreed to participate in an individual telephone interview.

We conducted in-depth, semi-structured telephone interviews to elicit program planners’ detailed, reflective descriptions of their experiences planning and implementing promotora-led initiatives (Fitzpatrick and Boulton 1994, Maxwell 2005). Based on the ROLES conceptual model (O’Brien et al. 2009), we designed a semi-structured interview guide with the aim of exploring program planners’ conceptualization of promotoras’ role, recruitment, selection, and training. We designed open-ended questions and probes (Table 1) to ensure the flow of the conversation, clarify, and elicit further details (Warren 2002). The first author pilot tested the interview guide with a program planner who met the same criteria as those included in the study. Following the pilot test, we revised questions that were unclear or directive (Lindlof and Taylor 2002). The audio-recorded telephone interviews lasted between 30–90 minutes, with an average length of 60 minutes. Personal and program identifiers were not included in the interview transcripts.

Table 1.

Example questions and probes from the in-depth interview guide.

In general, what do your program’s promotoras do?

How did you recruit your promotoras?

How did you measure how your promotoras delivered the health program?

|

We also gathered program-specific information such as the type of organization, geographic location, health focus, and program and training language(s). Recruitment and data collection activities occurred between May and September 2010.

Data Analysis

The purpose of our data analysis was to describe how program planners of obesity-related health programs for Hispanic women conceptualized and operationalized the promotora role as they recruited and trained promotoras to implement obesity-related health programs for Hispanic women. The goal of the analysis was to further understanding of how program planners’ promotora role conceptualization influences the placement of promotoras within the wider spectrum of healthcare providers and sets role boundaries that frame the type and amount of promotoras’ activities and responsibilities.

We used a mix of inductive and deductive qualitative coding and analysis techniques combined with a constant comparison approach (Strauss and Corbin 1998). Three authors independently conducted initial open-coding of the same three interview transcripts, identifying key words and terms (e.g., in vivo codes), themes, relationships, questions, patterns, or sequences in the data (Infante et al. 2009). We compared these initial codes within and across the three interview transcripts then developed a common coding scheme. The resulting coding scheme was organized into a codebook and entered into ATLAS.ti v6 software program. Using this coding scheme, the first author then reread and coded the entire data set twice, identifying and comparing salient themes and patterns within and across the interviews (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). All authors contributed to the later stages of the analysis, which involved interpretation and representation of the major narrative themes and writing up the results (Huberman & Miles 2002).

Results

Sample

The sample of 24 planners included 21 women and 3 men from 22 distinct programs. Participants’ specific roles included program director (n=7), program coordinator (n=4), principal investigator (n=10), co-investigator/consultant (n=1), and promotora trainer (n=2). They represented diverse types of organizations including community based organizations (CBOs, n=8), universities (n=5), university-community based organization collaborations (U-CBOs, n=5), federally qualified health centers (FQHC, n=3), hospital-based programs (n=2), and a state government-run program (n=1). Of note, eight of the ten programs sponsored through universities and U-CBO collaborations were research studies.

Geographic representation included the following U.S. regions: Southwest (n=7), West (n=7), Midwest (n=3), Southeast (n=3), and East (n=2). Programs served both rural (n=8) and urban (n=14) populations and focused on Type II diabetes (n=7), obesity/weight management (n=6), family health/wellness (n=4), cardiovascular health (n=3), health literacy (n=1), general women’s health (n=1), and osteoporosis (n=1). All program curricula included lessons on physical activity and nutrition for obesity prevention. Eleven programs were bilingual (English-Spanish) and eleven were conducted in Spanish only.

Qualitative Findings

Planners conceptualized promotora roles based on personal experiences and understandings of the underlying philosophical tenets of the promotora approach. Their conceptualizations of promotora roles reflected the individual program definitions of the role, historical role conceptualizations, role expectations, methods of reimbursement, and levels of promotoras’ involvement. Recruitment and selection methods reflected planners’ conceptualizations and experiences of promotoras and whether or not promotoras were engaged as paid program staff or community volunteers. Planners described a variety of implementation approaches. In focusing on sustainability, they raised concerns and strategies related to continuation of the specific program, the intended health behavior change or activity, and the individual promotoras. In the following sections we describe the thematic findings in detail, providing examples and illustrations from the qualitative data.

Role Conceptualization: Local and Global Contexts and History

A common theme was the conceptualization of the promotora model as a participatory, community-based approach that naturally incorporated cultural sensitivity and accountability and aimed to further health equity and improves access to care. Program planners also conceptualized this model within the broader context of community engagement, where community leaders and members are involved in pinpointing resources and barriers to care. In the words of one U-CBO participant, promotoras were culturally competent and able to “best engage people [community members served in these programs] in the contexts of their lives.” Because promotoras often were part of the target population, they understood community members’ life circumstances and underlying social determinants of health and health behaviors within the context of the specific program.

Advantages and benefits of the promotora model for community health programs included equity and reach, particularly in relation to access to care. Program planners considered the use of promotoras as improving equity in access among Hispanic communities. Promotoras improved reach, especially among individuals and groups harboring feelings of distrust for U.S. medical providers and the healthcare system. One participant from a U-CBO partnership program described the promotora model as a way to empower community members to rely on peers within their social networks to provide health education, link them to health resources, and work with healthcare providers to prevent and treat illnesses.

Program planners described their conceptualization of the promotora role within the context and history of local projects, as well as within more global contexts and history. Planners’ made decisions regarding promotora roles based on factors such as the type of program (e.g., randomized control trial, community program), funding source (e.g., short term grant vs. longer term funding), and type of organization hosting the program, resulting in diverse renditions and variations on the promotora model. One university-based participant pointed out the salience of these program dimensions, arguing that they actually influenced the entire promotora model and that comparing different models was similar to “comparing apples and oranges.”

A few participants noted they had first encountered the CHW delivery model in a global context or associated it with immigrants, refugees, or individuals living in rural villages in South and Central American countries. Some identified the promotora role with Paulo Freire’s (1970) popular education methods, which actively involved learners as leaders of cultural circles or discussion groups with the goal of acquiring skills and knowledge while engaging in critical reflection. Others illustrated their role conceptualization through personal accounts of their involvement with promotoras or their personal experiences as promotoras in other projects. For example, one participant identified herself as one of the first promotoras in the state and described her personal trajectory from promotora to director of a promotora program.

Defining the Role and Identifying Role Expectations and Level of Involvement

Promotoras’ roles and duties varied within the context of each specific program. They included educator, health outreach provider, bridge or connector to education or health services, natural helper, participant recruiter, cultural broker, provider of social support, friend, social advocate, problem solver, and role model. Participants attributed promotoras’ effectiveness in serving as a bridge to connect the community with healthcare resources to their ability to understand the social and environmental influences on a community’s health and engage with community members to address their targeted needs:

They know the environment where they work. They know the services available, and they know the healthcare systems in place. So, they know all of these things, and they can put their knowledge to work to better the health of everyone around them because they are leaders within their community and because people will trust them. (CBO)

Because of this level of trust, promotoras were effective vehicles for disseminating information on how to access and pay for services.

Promotoras’ roles spanned the healthcare continuum from prevention to treatment and included involvement at varying levels in planning, recruitment, enactment, and evaluation stages of health programs. This participant captured the flexibility of the role:

I see the promotora model as the vision of an integrated approach to prevention where the promotora is part of that team. If you incorporate them in clinical settings they could begin to be part of that team. If you draw them in from the community, they can begin to do outreach and health education, health promotion, and then you can begin to integrate them into the health infrastructure. (CBO)

Another common theme was the conceptualization of the promotora model as an alternative to the dominant medical model of U.S. healthcare. Some participants clearly considered the promotora model to be a more effective method of providing healthcare and resources to underserved and hard to reach populations. Promotoras worked ‘with’ people or community members to improve health outcomes, in contrast to the paternalistic medical model approach of working ‘on’ people.

The promotora model is all about trusting that people can learn and use their own leadership skills to move them up. There is a huge resource in the community that is not being used, and the healthcare system traditionally uses a very paternalistic model, which has not necessarily given us the best results. (U-CBO)

In contrast to a medical provider-directed healthcare experience, the promotora peer health education model seeks to empower patients or program participants to make informed health decisions through education on health topics, modeling and teaching skills necessary for personal health management and decision-making.

Situating Role as Volunteer or Paid Employment

Diverse views regarding the issue of economic value and remuneration for promotoras’ work surfaced in the analysis, focusing on promotoras as community volunteers or paid employees. Although participants’ views may have reflected the context and finances of specific health programs, those who subscribed to the historically-based model tended to conceptualize the promotora role as that of community volunteer engaged in the sole purpose of contributing to social mobility within the community through education and empowerment.

There was wide recognition that this distinction between volunteer and paid employee was not simple, and that the type of work promotoras performed, regardless of compensation, involved more than simply showing up to a job. Several participants noted that promotoras’ work required patience, love, and dedication for the sake of the community. Whether programs involved paid or volunteer promotoras, there was consensus that promotoras deserved recognition and some type of compensation for their time, energy, efforts and services.

Challenges of Undefined Role Boundaries

Although there was certainly a high degree of agreement around the overall promotora model, there was no clear consensus among participants on the specific definition of the promotora role. A common theme across the data was the challenge of blurred boundaries of the promotora role. Some identified “promotora” as a broad umbrella term applied to a wide range of individuals involved in the provision of health education and services to their communities. For most, the widespread use of the term promotora did not reflect a single, functional definition or role description. One participant alluded to the loss of application of a “correct” concept and model in practice:

The word promotora or community health worker is so vastly used now. In reality, programs may use the name for this role, but they don’t have the correct concept of what a promotora is. And, if they don’t have the concept they don’t have a promotora model. (FQHC)

Embedded in the diversity and ambiguity across promotora role definitions and expectations was the challenge of evaluating promotora effectiveness and impact:

One of the challenges of the whole community health worker movement is that the roles have varied so widely, and we don’t have a lot of good effectiveness data. When we do, it is often with different populations, with different definitions of workers, different definitions of their roles. (University)

As a result, lack of easy access to effectiveness data on promotora programs was one of the major challenges for program planners, particularly those engaged in developing funding proposals.

Implementation: Recruitment Processes and Eligibility Criteria

In describing the implementation of the various promotora programs, participants again reflected their particular role conceptualizations and expectations. Program planners described a variety of methods to advertise for and recruit potential promotoras. One strategy was to ask current or former promotoras to identify individuals who possessed leadership qualities and community trust. Some programs implemented more formal recruitment processes, including holding information sessions and disseminating position announcements through different forms of media (e.g., Spanish language radio and newspapers), making announcements at community-based organizations, soliciting referrals from other community leaders, and sending position advertisement messages through community social networks. A common strategy was to employ a variety of recruitment methods to maximize the pool of applicants for the position.

Program planners discussed the importance of both formal and informal promotora eligibility and selection criteria. Language and community engagement were the most frequently cited eligibility criteria. Some programs required promotoras to be bilingual (English/Spanish); other programs accepted monolingual Spanish speakers. Most planners expected potential promotoras to have existing knowledge and relationships with the community; some required or preferred that promotoras work and/or live in the target community. Women with wider and more numerous social connections within the target population were well-suited for the promotora role:

It is important when you select promotoras that there is that potential for them to easily share their resources, knowledge, and support with people that are naturally in contact with them. So someone who is very socially isolated… doesn’t have contact with people to share information. (FQHC)

Few program planners reported using formal education requirements (e.g., high school, GED, or higher education) or prior experience working in health-related positions as eligibility or selection criteria. In contrast, personal qualities and a willingness to serve the community were consistently identified as a prerequisite:

I personally do not look for education. I do not look for how many years of community service they have performed or how much they know about nonprofits. I look more at their dedication, their loyalty. I look for their compassion, humility, and in my questions and interview strategy, I try to recognize these things. Everything else I can teach them. But I can’t teach them how to care for other people. (Hospital)

Although most program planners did not subscribe to a specific formal education requirement, several noted that in future programs they would include a minimal education as a promotora qualification. Lack of literacy could impede promotoras’ effectiveness in programs that involved providing assistance with completion of health-related and program evaluation forms:

As far as education is concerned, perhaps that should be one of the criteria more strictly adhered to. Some have very minimal ability to read or write in Spanish. We need people who can understand some research protocol and do some documentation. So we need people who are comfortable reading and writing. (University)

Selection, Hiring, and Training Procedures

The selection and hiring procedures organizations used to fill the positions in promotora-delivered programs varied widely. At one end of the spectrum were two programs that had no promotora selection process. Any individual interested in serving the community could participate in the training and become a volunteer promotora. Another format, used by several CBO and U-CBO-based programs, was to hold training sessions for larger cadres of community members, with the dual purpose of providing the community with a free service (e.g., health education) and having an opportunity to observe the communication and leadership potential of potential promotoras. During these trainings, which often involved opportunities for role play and enacting other skills such as leading small groups, program planners were able to observe potential promotoras in action and judge their fit for the program requirements. Planners tended to consider promotoras’ willingness to learn and to serve their communities more than educational achievement and prior work experience. One hospital-based participant stated selection criteria included promotoras’ demonstrated enthusiasm for promoting health in their social networks and the “fire in their eyes.” Other desirable characteristics and traits included openness, compassion, empathy, nonjudgmental character, leadership qualities, and ability to relate to others. Program planners extended invitations to individuals they deemed to have the desired characteristics for the position to serve as a promotora.

At the other end of the spectrum, in some of the programs with salaried promotoras, there was a formal job application process similar to that of any other paid employment (e.g., through the organizational human resources department). Of note, promotoras hired in states with CHW certification were required to complete certification training programs before they could work in the community.

Anticipated Outcomes: Sustainability of Program Processes, Results, and Promotoras

In describing their experiences with promotora-led programs, participants focused on several long-term outcomes. In programmatic terms, these included maintaining the necessary funding and community engagement necessary to sustain program activities and program agents (e.g., promotoras). They also identified the goal of sustaining the intended health behavior change or activity at individual and community levels. Due to the variety of organizational contexts (e.g., grant-funded research projects, hospitals), the express intent to sustain the particular promotora programs varied. Program planners associated with CBOs tended to have more concrete plans for sustaining the promotora programs, such as building community partnerships, identifying local program champions, and transferring responsibility to predetermined community stakeholders. In contrast, participants working on grant-funded research projects appeared to be more readily accepting of the fact that there were no contingency plans for program sustainability once funding ended. There were, however, a few reports of spontaneous promotora-led initiatives to continue delivering the health education initiative within their communities after the formal program was over.

Program planners envisioned promotora sustainability both in terms of maintaining the individual promotoras engaged over time and as contributing to their personal social and economic well-being and mobility. Some participants believed policy measures, such as standardizing the role of promotora, would create a more sustainable position for promotoras in the healthcare system, and their work could then be made reimbursable by government programs such as Medicaid and Medicare. Interestingly, several participants proposed that a desired long-term outcome of promotora programs was personal career development and improved social mobility among the individual promotoras. Thus, encouraging promotoras to build on the knowledge, skills, and connections they acquired through participation in the community health initiative to advance their personal education and career was also seen as contributing to sustainability.

Discussion

This study explored program planners’ conceptualizations of promotoras’ roles in U.S. obesity-related health programs for Hispanic women. Promotoras with extensive social networks and who speak the same language and share similar cultural backgrounds with community members are well-suited to deliver health outreach among U.S. Hispanics. Incorporating promotoras into community-based health programs is an appropriate strategy for addressing health and healthcare access disparities among Hispanics, while simultaneously building linkages and improving trust with the healthcare system and healthcare professionals. Although not a panacea for the lack of culturally and linguistically appropriate care or discriminatory practices, promotoras can make substantial contributions to improving relationships between ethnic minority communities and healthcare providers. Strong social ties, trust, and the ability to move between and across community and healthcare settings allows CHWs to make contacts and connections and bridge gaps (Peretz et al. 2012).

Importantly, participants in this study represented programs administered at local, community levels as opposed to larger-scale, national programs as seen in the international CHW literature (Earth Institute 2011, World Health Organization 2007). Further, our research examined promotora-delivered programs focusing on a specific health issue (i.e., obesity) among a specific population group (i.e., U.S. Hispanic women), whereas CHWs working within the contexts of other national health systems have more expanded roles (e.g., provision of primary care services to rural populations). As one program participant commented, making assumptions about such very different CHW programs and models is akin to “comparing apples and oranges.” Despite these differences, a common characteristic of the CHW approach is the selection and training of members of the target population to reach marginalized populations with health information and services (Gilson et al. 1989; HRSA 2009).

Although Hispanics are the largest ethnic minority in the US, they do not constitute a monolithic ethnic entity. Health status and access to care among Hispanics depends on set of complex interactions, including but not limited to ethnic heritage and background, cultural beliefs, attitudes and practices, nativity, immigration status, language proficiency and utilization, geographic location, and socio-economic resources (Jerant et al. 2008). Therefore, promotora interventions need to be tailored to the social, cultural, linguistic, and environmental characteristics and contexts of local Hispanic communities.

Historically, lack of defined roles and activities for CHWs/promotoras led to challenges in sustaining community-based CHW-led programs (Earth Institute 2011). In our study, we found wide variation among program planners’ descriptions of the promotoras’ particular roles and activities. Promotoras’ blurred role boundaries may negatively affect the type and amount of work they perform (e.g., overburdening promotoras with too many roles); may be related to work inefficiencies (e.g., oversight of work expectancies); and may provoke difficulties in promotoras’ work environments (Brownstein et al. 2005, O’Brien et al. 2009, Swider 2002). Therefore, program planners should set parameters of activity levels and roles for their individual program’s promotoras to reduce their risk of developing job burnout (Altpeter et al. 1999, Bishop et al. 2002, Brownstein et al. 2005). Having clearly defined role boundaries will also facilitate program planners’ evaluation of promotora effectiveness (Altpeter et al. 1999). Program specific role definitions could assist researchers and practitioners in the development of evaluation criteria for selecting their program’s promotoras. Such criteria could influence the type of interview questions or skills-based activities used to select future promotoras. As part of program evaluation, planners and researchers could interview health program participants to identify which of the promotoras’ personal traits (e.g., personality characteristics) and more formal traits (e.g., language spoken) made them most effective and qualified to engage their communities to participate in the health program. Researchers could also interview program participants that remained in the study and those who discontinued the program to examine how the promotora-participant relationship affected the study or intervention participation. They could also conduct network analyses to measure how these community health workers expanded the healthcare information and outreach within their communities.

The implementation of standardized training programs and formalization of roles and responsibilities can foster sustainability of promotora positions within health programs (Earth Institute, 2011). In this study, program planners who advocated for promotora certification also saw the creation of role definitions as the first step to making this job a formal and sustainable position within healthcare organizations. This finding is consistent with research that advocates credentialing promotoras in order to formally recognize their role as a healthcare provider and, in turn, reimburse their work via government funding programs such as Medicaid and Medicare (Dower et al. 2006). Further, promotora certification has been linked to promotora career advancement, enhanced earning capacity, retention, personal status, and self-worth (Kash et al. 2007). Clearer role definitions and expectations in conjunction with recognized certification processes would not only contribute to promotora sustainability within specific programs and the broader healthcare system, but enhance individual well-being.

One of the major debates around CHWs revolves around their incorporation into the paid healthcare workforce. Currently, countries across Latin America, Africa, and Asia recognize and remunerate CHWs as members of the formal healthcare workforce (Jong-Wook 2003). The WHO reported an association between lack of monetary compensation and CHW/promotora turnover (Lehman and Sanders 2007). Although there is still considerable debate and controversy in the international literature about paying CHWs, there is little evidence of the long-term sustainability of programs utilizing volunteer CHWs (WHO 2007). Our findings indicated a wide range of opinions on the issue of promotoras as salaried workers or volunteers. We noted program planners tended to base their role conceptualizations regarding whether or not promotoras were treated as paid employees or volunteers on personal philosophies and financial considerations, a pattern consistent with past research (Swider 2002). Another interesting finding was how participants’ philosophical approaches may have influenced promotora selection procedures. When the role of promotoras was clearly defined as part of the paid multi-disciplinary healthcare team, program planners described more formal recruitment and selection processes, although the specific procedures varied based on program and organizational settings (e.g., university, FQHC, or CBO). In contrast, participants working in programs where the promotora role was strictly a volunteer position reported using more informal selection processes and providing small incentives (e.g., reimbursement for gas) for the volunteers. This approach is consistent with past research that concluded that offering multiple types of incentives (e.g., community recognition and reimbursement for expenses) was the best means to recruit and retain promotoras and CHWs (Bhattacharyya and Winch 2001).

Interestingly, even in programs where promotoras were paid employees, participants often reported selection criteria based on candidates’ personal qualities (e.g., respected by the community) and skills (e.g., listening skills) rather than on formal qualifications such as education and experience. Similar to findings reported by O’Brien and colleagues (2009), these planners hired promotoras who exhibited “interest in subject material, willingness to learn, and compassion” (p. S264). Of note, there were no reports of promotora assessment or evaluation using specific or formal assessment tools, nor were there any reports of systematic assessments of candidates’ characteristics or qualities. An important area for program planning and evaluation is the development of criteria to help identify individuals best fit to serve promotoras to engage their communities and, further, program evaluation which includes how the promotora influenced program outcomes.

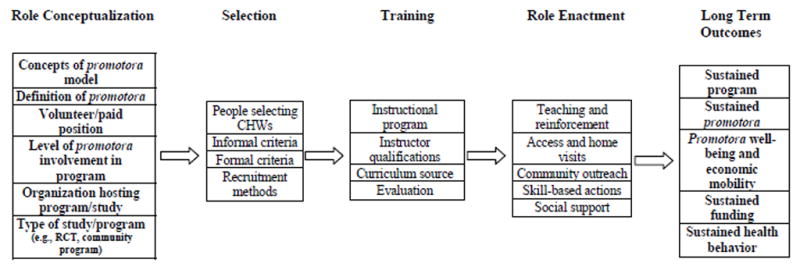

Based on these findings, we expanded the ROLES model (Figure 1) to include more specific aspects of promotora/CHW role conceptualization (Figure 2). For example, we now include program planners’ conceptualization of the role of promotoras and the overall CHW delivery model, how they define promotoras (Bishop et al. 2002), role expectations, whether or not the promotoras are paid for their efforts, and the level of involvement they will have within the intervention or program. We suggest the need for program planners to recruit and select promotoras based on program-specific role conceptualization and implementation. Role conceptualizations may differ based on intervention size, population served, program health focus, and expected promotora activities.

Figure 2.

Linking Promotora role conceptualization. preparation, enactment, and outcomes (Adapted and expanded from O’Brien el al. (2009) for Promotoras de Salud). Components presented in bold font are based on this study’s research findings.

The modified model (Figure 2) also reflects ways in which both program planners and promotoras sustain the health program in their communities after the initial program funding has ended. Future researchers could examine and possibly modify program delivery and dissemination procedures and long term outcomes. This expanded model is a framework to guide planning, implementation, and evaluation of health programs. More clearly defined promotoras role expectations and boundaries will allow for more specific role evaluation criteria. Further, the use of this model could lead to the development of promotora recruitment, selection, and training protocols which would help promote greater encouragement of collaborations with promotoras in healthcare programs (O’Brien et al. 2009).

It is important to note the limitations of the study. Potential selection bias related to our use of a convenience sample exists; however, we used a purposive sampling technique to ensure a wide variety of planners’ perspectives and experiences working with promotoras. Although this study provides a variety of planners’ perspectives, due to the small sample size and the formative aim of the research study, it is difficult to categorize these programs (e.g., paid versus unpaid, use of formal criteria for promotora selection) and link them to program characteristics. Because outcome evaluation data was not available for all programs, we were unable to examine any measures of promotora program success or program planner satisfaction with the promotora model. Our findings should not be generalized to the larger population of program planners working with promotora-led health programs for U.S. Hispanic women, but may inform the work of other planners and researchers.

Conclusion

This exploratory study examined how planners’ promotora role conceptualizations are associated with recruitment and selection of promotoras among select programs serving U.S. Hispanic women. This is important because promotoras serve as the spokespeople of the community-based health programs and often as the bridge between specific populations and access to their country’s healthcare system at large. In a global context, promotoras provide care to marginalized populations, particularly within countries that struggle with a shortage of healthcare providers (Jong-Wook 2003).

We asked participants for the specific details, criteria, and processes by which they selected promotoras for their health programs. Program promotora position descriptions differed according to the type of program being held, the program’s health focus, program context and environment, and required promotora qualifications. The findings suggest that promotoras’ role descriptions and boundaries may be delineated, negotiated, reviewed, and revised as programs evolve. This is an area for further consideration by researchers and CHW program planners, as role descriptions and parameters influence the type of training promotoras’ need, the activities they perform, and the degree to which they are integrated into the community and overall health system (Haines et al. 2007).

U.S. and international-based promotora-led programs have been successful in linking underserved populations and communities to healthcare, thus reducing health disparities (Lehman and Sanders 2007; Ingram et al. 2008). The outcomes of this study may apply to health program planners worldwide to demonstrate the need to create program specific promotora position descriptions which may, in turn, reduce the ambiguity of promotoras’ position within the healthcare setting (Lehman and Sanders 2007). It may also guide the development of protocols for recruiting and selecting promotoras while also leading to further development of evaluation methods for promotora programs (O’Brien et al. 2009). Ongoing attention to consistency and congruence across promotora role expectations, recruitment and selection criteria, and training, support, and evaluation processes will contribute to enhancing the effectiveness of promotora-delivered community health programs and potentially lead to expediency in addressing health disparities. Further, promotora program effectiveness data could support the need to integrate this workforce into permanent, sustainable positions into national healthcare systems (Brownstein et al., 2005; Lehman and Sanders, 2007).

Footnotes

We use the feminine form, promotora rather than the masculine promotor to reflect the predominantly female community health worker population in the Hispanic-serving programs surveyed in this research.

Contributor Information

Alexis Koskan, Email: alexis.koskan@moffitt.org, Dept. of Health Outcomes and Behavior, Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL, 33612; Tel: 813.745.1926; Fax: 813.745.1442

DeAnne K. Hilfinger Messias, Email: deanne.messias@sc.edu, College of Nursing and Women’s and Gender Studies Program, University of South Carolina.

Daniela B. Friedman, Email: dfriedma@mailbox.sc.edu, Department of Health Promotion, Education, and Behavior, Arnold School of Public Health, University of South Carolina

Heather M. Brandt, Email: hmbrand@sc.edu, Department of Health Promotion, Education, and Behavior, Arnold School of Public Health, University of South Carolina

Katrina M. Walsemann, Email: kwalsema@mailbox.sc.edu, Department of Health Promotion, Education, and Behavior, Arnold School of Public Health, University of South Carolina.

References

- Aiken LH, Cheung RB, Olds DM. Education policy initiatives to address the nurse shortage in the United States. Health Affairs. 2009;28:646–656. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.4.w646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altpeter M, et al. Lay health advisor activity levels: Definitions from the field. Health Education & Behavior. 1999;26:495–512. doi: 10.1177/109019819902600408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JO, et al. Use of community health workers in research with ethnic minority women. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2004;36:358–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2004.04064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth BE, Kreiner GE, Fugate M. All in a day’s work: Boundaries and micro role transitions. The Academy of Management Review. 2000;25:472–491. [Google Scholar]

- Balcazar H, et al. Salud Para Su Corazón-NCLR: A comprehensive promotora outreach program to promote heart-healthy behaviors among Hispanics. Health Promotion Practice. 2006;7:68–77. doi: 10.1177/1524839904266799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baquero B, et al. Secretos de la Buena Vida: Processes of dietary change via a tailored nutrition communication intervention for Latinas. Health Education Research. 2009;24:855–866. doi: 10.1093/her/cyp022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya K, Winch P. Community health worker incentives and disincentives: How they affect motivation, retention, and sustainability. Arlington, VA: Basic Support for Institutionalizing Child Survival Project (BASICS II) for the United States Agency for International Development; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop C, et al. Implementing a natural helper lay health advisor program: Lessons learned from unplanned events. Health Promotion Practice. 2002;3:233–244. [Google Scholar]

- Braveman P. Health disparities and health equity: Concepts and measurement. Annual Review of Public Health. 2006;27:167–194. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownstein JN, et al. Community health workers as interventionists in the prevention and control of heart disease and stroke. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2005;29:128–133. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed 21 April 2012];Healthy People 2012: Final Review. 2011 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hpdata2010/hp2010_final_review.pdf.

- Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. Retrieved June 28, 2010 from http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241563703_eng.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cossrow N, Falkner B. Race/ethnic issues in obesity and obesity-related comorbidities. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2004;89:2590–2594. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crigler L, Jacobs T, Wittcoff A. [Accessed 10 February 2011];Sustainable, successful community health worker programs. 2009 Available from http://www.maqweb.org/miniu/presentations/LCriglerCHW%20MiniU%202009v3.pdf.

- Dower C, et al. Advancing community health worker practice and utilization: The focus on financing. San Francisco, CA: National Fund for Medical Education; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Earth Institute. [Accessed on 2 July 2012];One million community health workers. 2011 Available from http://www.millenniumvillages.org/uploads/ReportPaper/1mCHW_TechnicalTaskForceReport.pdf.

- Fitzpatrick R, Boulton M. Qualitative methods for assessing healthcare. Quality in Healthcare. 1994;3:107–113. doi: 10.1136/qshc.3.2.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freire P. In: Pedagogy of the oppressed. Ramos Myra B., editor. Continuum; New York: 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Gee GG, Ford LF. Structural racism and health inequities: Old issues, new directions. Du Bois Review. 8:1–18. doi: 10.1017/S1742058X11000130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilson L, et al. National community health worker programs: How can they be strengthened? Journal of Public Health Policy. 1989;10:518–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines A, et al. Achieving child survival goals: Potential contribution of community health workers. The Lancet. 2007;369:2121–31. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60325-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Resources and Services Administration. [Accessed on 9 February 2011];Community Health Workers National Workforce Study. 2009 Available from: http://bhprhrsa.gov/healthworkforce/cwh/2.htm.

- Huberman AM, Miles MB. The qualitative researcher’s companion. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Infante C, Aggleton P, Pridmore P. Forms and determinants of migration and HIV/AIDS-related stigma on the Mexican--Guatemalan border. Qualitative Health Research. 2009;19:1656–1668. doi: 10.1177/1049732309353909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram M, et al. Community health workers and community advocacy: Addressing health disparities. Journal of Community Health. 2008;33:417–424. doi: 10.1007/s10900-008-9111-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA. Social networks and social support: Implications for natural helper and community level interventions. Health Education Quarterly. 1985;12:65–80. doi: 10.1177/109019818501200106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson EJ, Parks CP. Recruitment and training issues from selected lay health advisor programs among African Americans: A 20-year perspective. Health Education & Behavior. 1997;2:418–431. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerant A, Arellanes R, Franks P. Health status among US Hispanics: Ethnic variation, nativity, and language moderation. Medical Care. 2008;26:709–17. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181789431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jong-Wook L. Global health improvement and WHO: Shaping the future. The Lancet. 2003;362:2083–2088. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15107-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kash BA, May ML, Tai-Seale M. Community health worker training and certification programs in the United States: Findings from a national survey. Health Policy. 2007;80:32–42. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller CS, Cantue A. Camina por Salud: Walking in Mexican-American women. Applied Nursing Research. 2008;21:110–113. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, et al. The impact of lay health advisors on cardiovascular health promotion: using a community-based participatory approach. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2004;19:192–199. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200405000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman U, Sanders D. Community health workers: What do we know about them? The state of the evidence on programmes, activities, costs and impact on health outcomes of using community health workers. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lindlof TR, Taylor BC. Qualitative communication research methods. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall KJ, et al. Health status and access to health care of documented and undocumented immigrant Latino women. Health Care for Women International. 2005;26:916–936. doi: 10.1080/07399330500301846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell JA. Qualitative research design: An interactive approach. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien MJ, et al. Role development of community health workers. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;37:S262–269. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, et al. [Accessed on 16 May 2012];Prevalence of obesity in the United States: 2009–2010. 2012 Available from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db82.pdf.

- Peretz PJ, Matiz LA, Findley S, Lizardo M, Evans E, McCord M. Community Health Workers as drivers of a successful community-based disease management initiative. American Journal of Public health. 2012;102(8):1443–1446. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, et al. Lay health advisor interventions among Hispanics/Latinos: A qualitative systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;33:418–427. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss AL, Corbin JM. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Swider SM. Outcome effectiveness of community health workers: An integrative literature review. Public Health Nursing. 2002;19:11–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2002.19003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren CA. Qualitative interviewing. In: Gubrium JF, Holstein JA, editors. Handbook of interview research: Context and method. New York: Thousand Oaks; 2002. pp. 83–101. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. [Accessed on 20 February 2010];Declaration of Alma-Ata. 1978 Available from: http://www.who.int/hpr/NPH/docs/declaration_almaata.pdf.

- World Health Organization. Strengthening the performance of community health workers in primary health care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1989. World Health Organization Technical Report Series 780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. [Accessed on 2 July 2012];Community health workers: What do we know about them? 2007 Available from: http://www.who.int/healthsystems/round9_7.pdf.

- Zerubavel E. The fine line: Making distinctions in everyday life. Free Press; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman MA. Empowerment theory: Psychological, organizational, and community levels of analysis. In: Rappaport J, Seidman E, editors. Handbook of Community Psychology. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2000. pp. 43–63. [Google Scholar]