Abstract

Background

Role functioning is an important part of health-related quality of life. However, assessment of role functioning is complicated by the wide definition of roles and by fluctuations in role participation across the life-span. The aim of this study is to explore variations in role functioning across the lifespan using qualitative approaches, to inform the development of a role functioning item bank and to pilot test sample items from the bank.

Methods

Eight focus groups were conducted with a convenience sample of 38 English-speaking adults recruited in Rhode Island. Participants were stratified by gender and four age groups. Focus groups were taped, transcribed, and analyzed for thematic content.

Results

Participants of all ages identified family roles as the most important. There was age variation in the importance of social life roles, with younger and older adults rating them as more important.

Occupational roles were identified as important by younger and middle-aged participants. The potential of health problems to affect role participation was recognized. Participants found the sample items easy to understand, response options identical in meaning and preferred five response choices.

Conclusions

Participants identified key aspects of role functioning and provided insights on their perception of the impact of health on their role participation. These results will inform item bank generation.

Keywords: Role functioning, Focus group, Life-span

The term “role” started appearing in behavioral science literature as early as 1920 [1, 2], followed by a rapid increase in its use in various fields. The concept has been studied extensively within the context of two distinct theoretical frameworks, namely structuralism and symbolic interaction [2, 3]. Gradually, the body of work accumulated in the study of roles came to be known as “role theory”, even though it has been readily recognized by proponents that the field consists of many hypotheses and loosely related concepts, which even if diligently organized “would undoubtedly not constitute a single monolithic theory” [1]. Similarly there is no clear consensus as to how to define “social role”. For example, in the study of roles, psychologists focused more on the self, personality and individual response, while sociologists defined roles more in terms of interaction between two or more persons in a social system [4]. In the area of outcomes measurement, a more pragmatic definition has been accepted and role functioning was used as referring to the capacity of an individual to perform activities typical to specific age and particular social responsibility [4, 5].

In 1948, the World Health Organization defined health as not only the absence of disease, but also the presence of physical, mental and social well-being [6]. With the introduction of social well-being as part of the definition of health, assessment of role functioning became an important outcome in health research. The new paradigm of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) [6] also calls for separate measurement and interpretation of role functioning and participation. The ICF serves both as a conceptual model and as an assessment tool that can be used for functional description, intervention targeting and outcome measurement [7, 8].

Our theoretical conceptualization of the role performance construct was inspired by the biopsychosocial model of health and disability and the ICF. The ICF postulates three levels of person’s functioning and presents it as a dynamic interaction between health conditions, environmental and personal contextual factors. The classification system is completed through the use of qualifiers describing the presence and severity of problems in each of these levels.

While the ICF classification has proven useful, there has been some confusion in the literature regarding the distinction between the concepts of “Activities and Participation”, represented by a single combined classification in the ICF [8–11]. A recent conceptual clarification was proposed by Badley [8], where the activities and participation category was subdivided into acts, tasks and societal involvement. Of particular interest to our work is the category of “societal involvement”, which is defined by social role and views the individual as a player in socially recognized areas of human effort. Our research focuses on the functioning of an individual in relevant roles within this broader context of societal involvement of the ICF.

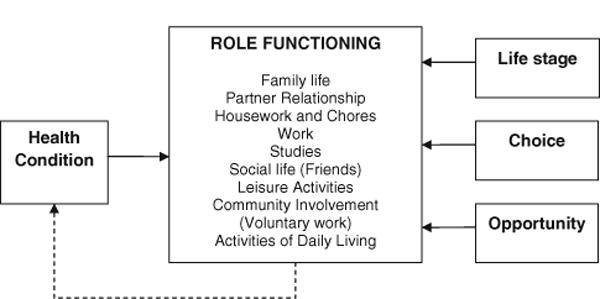

Using this theoretical framework, a more focused model of role functioning was developed (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model of role functioning

The model defines role functioning as involvement in life situations related to family life, partner relationship, household chores, work for pay, studies, social life (including interactions with friends), leisure time activities, community involvement (including volunteer work) and everyday living activities. Consistent with ICF, the influences of personal and environmental factors on role functioning were postulated, focusing specifically on the effects of life stage, choice and opportunity for participation in specific roles. The model also recognizes the bidirectional relationship of health condition and role functioning: health status can lead to limitations in role functioning, but changes in role participation may also influence health. However, the current work focuses on role functioning as an outcome measure.

As a result of the overall shift in paradigms toward inclusion of social aspects in the definition of health, there has been a surge in the development of a large number of measures of social participation and social role functioning [12, 13] that played an important part in the research on social aspects of impact of disease on functioning and human aging [14]. Role participation and functioning measures have been reviewed within the fields of handicap or disability research [15, 16], psychiatry [17] the ICF framework [9], and general outcomes research [18]. Additional reviews have been done focusing on occupational roles [19–21]. Together, these reviews identify more than 40 generic measures assessing aspects of role participation and targeting different populations. Even more scales can be found in disease-specific instruments. Role functioning measures appeared both as subscales in generic multi-domain health-related quality of life instruments (e.g. SF-36 [22]) and as stand-alone measures (e.g. the Role Functioning Scale [23]). Various theoretical perspectives and approaches have been used in the development of these measures, but most can be viewed as loosely related to role theory or the WHO model of disease, as measures assess level of functioning as part of a social role.

Existing measures are quite diverse in format and focus of assessment, comprehensiveness, psychometric properties, areas of use and popularity with researchers. Most measures are static in the sense that all respondents are answering the same items. Some disease or condition-specific measures [24–27] and one generic measure [28] use a computerized adaptive testing. This approach requires a large bank for items concerning role functioning. From this item bank, the most relevant items are selected for each respondent based on his or her answers to previous items. Test scores are estimated using item response theory [29] to achieve comparable scores even though the respondents are not answering the same items. The purpose of our project is to develop such a computerized test.

The current paper reports on the first step of the item development, namely a focus group study. There has been an increased appreciation of the importance of qualitative methods in the initial stages of measurement development, as evidenced by the increased numbers of publications [28, 30–35] and formal draft guidelines for the pharmaceutical industry [36]. Focus groups, as a form of qualitative exploration, can contribute to measurement development in several important ways. First, they provide a forum, where members of the target group can provide input on the development of items [37]. Second, they can inform the content of the measures by revealing the meaning of the construct of interest to the target group. Third, they can provide insights into the wording of the items and response options [30]. Fourth, discussions can help identify potential gaps in item coverage.

The specific aim of this project was to use a qualitative approach in the initial stages of development of an item bank assessing the impact of health status on role participation. More specifically, the research goals were to:

Explore the meaning of the concept of a social role

Evaluate the content and relevant importance of social role domains and compare the results to the ICF-based model

Explore age variations in the importance and relevance of various social roles

Test item wording and response format with a set of sample items.

Methods

Participants

Eight focus groups with 4–8 participants were planned for this study. To address the potential differences in gender roles and age-related roles, participants were recruited in separate gender and age groups. Four groups were planned separately for men and women in age groups 18–25, 26–45, 46–65 and 65+. The goal was for 50% of participants to have a chronic condition (e.g. asthma, heart disease, diabetes, autoimmune disease etc.). Participants with no chronic conditions were also included in the study to ensure contrasts in experience and to make the questionnaire understandable for patients and non-patients. A convenience sampling approach was used and participants were recruited through advertisements distributed in local community centers, university message boards and listserves. Information on other demographic variables (ethnicity and education) was recorded but was not used for quota sampling since this deemed unfeasible. Interested individuals who called were provided with brief description of the study over the phone and invited to participate in a focus group corresponding to their gender and age.

Materials

Moderator’s guide

The discussion content was outlined in a carefully constructed moderator’s guide with key topics and questions of the discussion.

Domain ranking cards

Nine key role domains, identified through review of the literature (family life, work, study, housework and chores, partner relationship, community involvement, social life, leisure, activities of daily living), were listed on separate cards. A set of ranking cards was prepared for each participant ahead of time. Participants were asked to organize the cards in order of importance and then write a ranking number on them (1 being the most important).

Sample items form

Eighteen sample items were developed and presented to participants (see Table 1). Items were designed to assess one of the nine domains used in the ranking cards (1–3 items per domain). All items included health attribution (e.g. “In the past 4 weeks how much did your health limit your ability to go out with friends?”), but varied in the following item characteristics of interest:

Statement versus question format.

Recall period (no recall period, 2, 4 weeks).

Number of response categories (4 vs. 5).

Different wording of response categories.

Table 1.

Sample of items presented in the focus groups

| Role domain | Item |

|---|---|

| Social life | In the past 4 weeks, how much did your health limit your ability to go out with friends? (Not at all, A little, Somewhat, Quite a bit, A lot) |

| I am doing less of the things that I enjoy because of my health (Absolutely agree, Mostly agree, Somewhat agree, Do not agree at all) | |

| Occupational life | In the past 4 weeks, how much did your health affect your ability to manage your time at work? (Not at all, A little, Somewhat, Quite a bit, A lot) |

| My health affected my job satisfaction over the last 2 weeks. (Not true at all, Somewhat true, Mostly true, Absolutely true) | |

| Family life | My health has interfered with my family life over the last 4 weeks (Not at all, A little, Quite a bit, A lot) |

| The relationship with my partner was affected by my health over the last 4 weeks (None of the time, A little of the time, Some of the time, Most of the time, All of the time) |

No changes to the item content or format were made throughout the duration of the study and the same set of items was presented to all participants.

Socio-demographic form

A form with questions on gender, age, ethnicity, level of education, occupation and chronic conditions was also presented and completed by participants at the end of the discussions.

Procedure

The discussion began with the moderator presenting the aim of the project and describing the procedure and the ground rules of a focus group discussion. This was followed by brief presentation from each of the participants. The content discussion started with participants sharing their definitions and understanding of the term “social role” and the relationship between health and the ability to participate in various social roles. This was followed by a review of all social roles that participants identified as part of their life and the impact that health has on these roles. In addition the relevant importance of role domains were assessed in the discussion through ranking of the nine key domains. Each participant performed the ranking individually and then the results were discussed in the group.

The subjective perception of the change in social roles relevance and importance across each individual’s life course was discussed next. Participants were asked to think about the past 10 years and the next 10 years of their life and write the three most important roles for them at that time. Any reported changes were discussed in the group.

In the last part of the discussion participants were presented with the sample item form containing items assessing role functioning in various domains and using different response formats. Participants were given some time and asked to answer each of the presented questions on the form individually. The overall perception, readability, format and preferences for response options were discussed next. Finally, participants completed a brief form with socio-demographic questions.

All focus groups were conducted in a convenient, easily accessible location. The duration of the discussions ranged between 1 h and 1 h and 45 min. Refreshments were provided for participants and a $50 gift card was presented at the end of the discussion, as an incentive for their participation. The study procedure was reviewed and approved by the New England IRB. All participants were presented with and asked to sign a consent form on the day of the group discussion.

Analysis

All focus group sessions were audio-taped, transcribed (without paraverbal expressions) and analyzed using content-analysis and grounded theory framework. The transcriptions of the focus group discussions, the group notes and answers on forms presented during the discussion were the basic material for the content analysis. A number of steps were followed in the analysis process. First, a set of dimensions and coding rules were formulated based on information derived from theory, review of existing measures and literature. Codes were selected to reflect participation in different social roles, examples of disease impact on that participation, variation of the roles across the lifespan and reactions to presented items. If needed, the codes were refined and supplemented throughout the analysis.

The analyses of the sample items review summarized overall perception of readability and format of the items and, in addition, focused on the 5 specific research questions: (1) Perceptions of the use of health attribution in the items; (2) Evaluation of preferences in recall period; (3) Evaluation of preferences in the number of response categories; (4) Evaluation of perception of the influence of wording of response options on participants’ answers; (5) Evaluation of statement versus question format of presentation.

All results from the group discussions were summarized and used in item development for the role functioning item bank.

Results

Sample and process

A total of 38 English-speaking adults (mean age 41(range 18–79), 43% female, 79% Caucasian, 62% with chronic conditions distributed across all groups) participated in eight focus groups (Table 2). The minimum targeted number of four participants per group was achieved in all but one of the groups, where two of the enrolled participants failed to arrive, resulting in a group of 3 (group size range 3–9 participants). Overall, all the discussions went smoothly and followed the outline of the moderator’s guide.

Table 2.

Sample demographic characteristic

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Mean 41 | (18–79) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 22 | 42.11 |

| Female | 16 | 57,089 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Black or African-American | 5 | 13.16 |

| White | 30 | 78.95 |

| American Indian/Alaskan native | 1 | 2.63 |

| Other | 1 | 2.63 |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 | 2.63 |

| Education | ||

| High school graduate | 11 | 28.95 |

| Some college | 17 | 44.74 |

| College graduate | 5 | 7.89 |

| Postgraduate education or degree | 6 | 15.79 |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 | 2.63 |

| Occupation | ||

| Student | 11 | 28.95 |

| Working at a paying job | 12 | 31.58 |

| Retired | 8 | 21.05 |

| Laid off or unemployed, but looking for work | 0 | 0 |

| A full-time homemaker | 3 | 7.89 |

| Other | 4 | 10.53 |

| Chronic conditions | ||

| Asthma | 6 | 16.22 |

| Back Pain | 7 | 18.92 |

| Diabetes | 4 | 10.81 |

| Auto-immune disease | 1 | 2.7 |

| Heart disease | 2 | 5.41 |

| Other chronic condition | 3 | 8.11 |

| None | 14 | 37.84 |

| Income | ||

| Less than $5,000 | 2 | 5.26 |

| $5,001 to $20,000 | 6 | 15.79 |

| $20,001 to $45,000 | 10 | 26.32 |

| $45,001 to $75,000 | 10 | 26.32 |

| More than $75,000 | 5 | 13.16 |

| Prefer not to answer | 5 | 13.16 |

Definition of social roles and functioning

The meaning of “social role” for study participants was characterized by social position, behavioral expectations and interpersonal interactions. Participants described social role with phrases like “it is…where you fit in society”, “knowing your spot”, “how you interact with people”, “the norms that society sets saying how to act”. In addition, many spontaneously provided examples of what they considered to be covered by the construct. The most commonly provided examples were family roles and corresponding responsibilities. Family roles (e.g. mother, father, older brother, grandmother) were provided as an example in all groups, with a stronger emphasis on partner relationship in the middle-aged groups. Occupational roles were also commonly mentioned as examples for social role functioning, but in two of the female groups, these examples were not given spontaneously. Additional associations with the term were made with gender, race, various communities (e.g. friendship groups, fraternity, neighborhood, volunteer organization). In this general discussion, participants also recognized the potential impact that health could have on performing in pertinent social roles, ranging from raised anxiety and making you uncomfortable in certain situations to limited functioning and inability to participate in the role at all.

Role functioning domains

Family life

Family roles were most commonly mentioned as an example for social role participation. They were discussed at length in all groups and participants rated them as most important. The importance of family roles was universally associated with the interconnectedness of family members, described in terms of “responsibility”, “support” and “emotional support” provided by family members. Raising children and taking care of family members was another prevalent theme in the groups. Not surprisingly, this aspect of family life was most important for participants with children in the household, who extensively discussed their responsibilities and were more likely to define one of their family roles as a “provider”. The importance of the relationship with a partner was also universally recognized, and while it was described as specific, it was nevertheless discussed within the context of family relations. For participants who had no children, the partner relationship was synonymous with family life, while for participants with larger families, partner relationship was recognized as an important integral part of family life. Finally, doing chores was also discussed universally as part of family roles and responsibilities. Difficulties with chores were often provided as an example of health impact on role participation.

There were some themes that emerged in some of the groups, but were not mentioned in others. For example, younger participants in both the male and female 18–25 groups considered being a “role model” for younger siblings and young children as an important part of being a family member. For older adults, on the other hand, communication with family members, both face to face and over the phone was more often discussed as an important part of family life. In three of the groups with participants over 45 years, “role reversal” was discussed in the cases where adult children were taking care of aging parents.

There were also some gender differences noticeable in the discussions. Several family roles and associated activities were mentioned only in the female groups, namely being a playmate for children and grandchildren, being a caregiver, and worrying about the health and well-being of family members. In addition, while the role of a “provider” was discussed in all groups, men tended to associate “providing” more with financial support, while women provided caring and comfort.

When the impact of health on family roles was discussed, it was widely pointed out that the type and level of impact would depend greatly on the type of health problems (Table 3, I.1.). The range of impact was also illustrated by the varying examples provided by participants with no chronic health conditions and participants affected by some chronic disease with different levels of severity. The lowest level of impact was illustrated by examples concerning emotional reactions to occasional sickness or worries over the future impact of a chronic condition that does not yet have any serious adverse effects (Table 3, I.2.–4.). The widest range of examples was provided for health problems that in some way limit participation and ability to perform tasks related to family roles, such as financially supporting the family, playing with children, doing chores around the house and providing support to family members (Table 3, I.5.–7.). Finally, examples provided by participants with the most severe health problems discussed a level of role limitations so severe that it created a sense of dependency on other family members, loss of self and feeling of being a burden (Table 3, I.8.–9.).

Table 3.

Sample participants’ discussion quotes

|

Occupational life

The importance of primary occupation as an area of social role participation was recognized in all groups. One of the main topics of discussion was the importance of work and the demands of individual occupational roles. Work was defined by participants primarily as a source of financial freedom and a way to “provide for one’s family”. It was also recognized, however, that occupational roles “give some structure” to everyday life, “teach values” and, in particular, work ethics, and allows an individual to work on personal growth and “learn new things”. For some participants, work occupation was so important that they defined it as the role that “makes you somebody”.

Studying and the role of a student was also part of the discussions. In all groups, the role of a student was described as occupational and related to future career aspirations. As could be expected, the student role was most prevalent and important in the youngest groups, where it was also considered more important than any other occupational roles.

A large part of the discussion on occupational role was devoted to the potential impact that health could have on performance and participation. In all groups, participants readily recognized that the type of impact would vary dramatically, depending on the health problem.

The easiest health impact to recognize was absenteeism, expressed in concerns of potentially exceeding the number of available sick and vacation days, due to a health problem (Table 3, II.1.–2.). Among employed participants with no chronic health problems, there was a degree of reluctance to acknowledge problems with job performance due to health issues. In an open discussion, they stressed the importance of performing “at 100%” when they were on their job, in order to meet job demands (Table 3, II.3.). When the questions were narrowed down further, to explore occasions when participants have gone to work in poor health, problems with motivation to perform, work output and speed of performance were mentioned (Table 3, II.4.–5.). Employed participants with chronic conditions discussed their concerns regarding the future impact of health on their occupation and hardships created by work demands on days when they do not feel well. Participants with chronic conditions or disability provided narratives of the impact of health on their work performance and the impact of job loss on their overall life (Table 3, II.6.–7.).

A noticeable difference in the importance and to some degree the meaning of an occupational role was noticed across different age groups. For younger participants, occupational roles were very important, and the main emphasis was on acquisition of new skills and self-improvement, in preparation for a desired future career (Table 3, II.8.–9.).

For middle-aged adults, the importance of occupational role was somewhat lower, and the meaning was more practical and with a current focus. For this age group, the importance of occupational role was primarily defined by the necessity of earning an income and supporting a family (Table 3, II.10.–11.).

For the oldest participants in the focus groups, occupational roles were least important. To them, occupational role was important primarily as a way to keep engaged and to learn new things, and is, to a large extent, substituted by volunteer work and community involvement (Table 3, II.12.–14.).

There were also some differences by gender in the comments made in relation to occupational roles. For example, some of the women in the 25–45 groups were staying at home and raising their children. They were the only subgroup of participants who stated that employment roles or student roles are not relevant at the time of the discussion. These participants described their primary occupation as being a homemaker and felt it is more relevant to family life and social roles than to work or occupational roles. Women who were working valued their professional accomplishments highly, but were less likely than men to view their occupational role as being “a breadwinner”.

Social life and community roles

The domains of social life and community roles were discussed after roles related to family and occupation. The only additional role (beyond roles related to family and occupation) that was mentioned by participants without prompting questions of these alternative domains was the role of a “friend”. The role of a friend was associated primarily with providing and receiving support, communications and just having fun. The role of a friend was much more important for participants in the 18–25 and 65+ groups, while members of the other groups reported lower importance, due to time conflict with family role demands (Table 3, III.1.–2.).

The impact of health problems on this role was expressed in a range from causing worries to the change/loss of friendship circles dictated by the inability to participate in certain activities.

A prompt by the moderator to think of participation in other roles related to social life, community involvement or leisure generated additional diverse examples, such as fraternity member, union member, gym partner, community leader, volunteer, neighbor, and community member. “Community” had different meanings for participants, including town, church, neighborhood, local politics, giving to charity and helping others.

Compared to family and occupational roles, the importance of roles related to social life and community involvement was relatively low, as evidenced by the shorter discussions, fewer examples, and lower rankings of these roles. However, there was variation in the level of the importance of these roles, related to life-span stage, with younger and older participants finding these roles more important than middle-aged adults. Some difference by gender was also noticed in the types of social roles considered important. Younger men mentioned various sports roles (e.g. team member, captain, workout partner etc.), while older women were more likely to discuss volunteer roles and community involvement. This variation in the level of importance can also be attributed to different role dynamics across life-stages as described in the next paragraph.

Domain dynamics

The role domains described previously were discussed separately in all groups, but the discussion also supported the interaction between these areas. Most noticeably, time demands of multiple roles in one domain affected the importance or even relevance of roles in other areas. The effect was strongest for participants in mid-life with dual occupational roles, who were also parents with children in the household. For them, social roles outside of work and family were of little importance, mainly due to the lack of time (Table 3, IV.1.–2.). The time conflict between increased demands of family and professional roles and the decline of importance of social life was recognized in some form in all age groups and in a way was perceived as a normative development. Younger participants recognized it in their comments for the expectation of changes in the importance and relevance of their roles in the future (Table 3, IV.3.–4.). Middle-aged participants recognized the change both through their comments on their current reduced involvement in social activities and in their retrospective accounts of changes in the role relevance and importance (Table 3, IV.5.–6.).

On the other hand, for participants with fewer or less time-demanding family roles, social and community participation was more important. Older participants in retirement had richer narratives of social life and community involvement (Table 3, IV.7.–9.).

Group discussions also provided evidence of temporal life-span dynamics, with changes of new role acquisitions and role loss. Not surprisingly, most dynamic in this respect were the narratives of younger and older adults, describing changes associated with role changes related to changing family roles and entering or leaving the work force.

When the impact of health on role participation was examined, participants recognized that all roles in all domains get impacted, especially in the case of serious conditions. This general impact was more readily recognized by participants currently suffering from chronic conditions (Table 3, IV.10.–11), but was also acknowledged by participants with no current health problems (Table 3, IV.12.). Particularly revealing were the accounts of participants where disease was associated with role loss. For example, many participants discussed the loss of the role as a “worker”, caused by retirement, parenthood, or career change, and in these cases, the role loss was not perceived as a negative event (Table 3, IV.13.–15.). However, when work role loss was caused by a health problem, participants perceived work loss as a disruptive negative event associated with depression and reduced quality of life (Table 3, IV.16.–18.).

Sample items review and item development

Overall, participants found the sample items to be clearly worded and easy to read, understand, and answer to. The use of health attribution in the items was perceived as helpful in “focusing” questions and did not raise any specific concerns. No specific comments were made in relation to the format used (question vs. statement). While the evaluation of the sample items was focusing primarily on their format, the content of the included items reflected many of the major topics in the focus groups. The only questions that emerged were about items for roles that were not relevant for the individual, e.g. a person was not always sure how to answer a question asking about work if he/she was not working. The consensus was that a “not applicable” option was needed for these questions when presented in a study.

Participants were also asked to evaluate several time frames of reference (2, 4 weeks, no specific time) in the items. The preference was given primarily for a 4 weeks recall period, as a timeframe that was short enough to recollect accurately and long enough to observe some changes. However, in all groups, it was pointed out that the best recall period would depend on the type of condition under study and the specific research question at hand.

The number of response options was also evaluated. There was some variability in the preference given. The majority thought that five response choices is the absolute maximum needed. Some respondents strongly preferred fewer response options, pointing out the difficulty in differentiating between the middle responses in a five point scale.

When the wording of the response choices was discussed, many diverse preferences were expressed, but none of them was very strong. The overall consensus in the groups was that the wording of the responses does not matter that much, as the responses are perceived as a scale with a positive, a negative and a neutral (middle) point, and the actual labels of these points would not change the answer to the question. Some participants expressed preference for uniformity of response choices used in a test.

In addition to the insights gained from the focus groups into the meaning of role participation in different life domains, 155 phrases describing the impact of health on role functioning were retrieved from the transcripts (Table 4). The information from the group discussions, participants’ phrases and revised sample items, along with theory, was used in the development of items to be included in a role participation item bank.

Table 4.

Sample phrases of health impact by role domain

| Role domain | Participant quote |

|---|---|

| Social life | I couldn’t do things I wanted to do… [like] hanging out with friends. They wanted to go out at night and I just wanted to die |

| With your friends, if everyone wants to go out and do something that you can’t do then that can separate you from them and can make a wall | |

| And also your friends change. Like your activities change with your friends, so you loose some friends and then you move on and you find some new friends | |

| And she cant go to competition for cheering cause her asthma is so bad | |

| Occupational life | I was sent to go home, because I was sick and I wanted to work, but you know if you’re not doing your job at a 100% they’re gonna let you know about it |

| I was out of work for an acute problem it affected us financially | |

| At work I get tired my feet hurt | |

| Family life | I was not able to provide for my family |

| So that affects the kids, affects everybody, because everybody notices it, even it is a simple thing like a back problem | |

| If you can’t do anything it puts the burden on the partner she has to do all of it | |

| Even though for a family it shouldn’t be a burden it would still in the back of their heads be |

Discussion

This focus group study described the original qualitative steps in the development of an item bank assessing health impact on role functioning. The study can be viewed broadly, as adding to the literature using qualitative approaches and focusing on understanding of lay experiences of health and illness [38, 39]. The narratives of respondents with chronic illness provided multiple illustrations of theoretical construct introduced earlier in the field. For example, in the comments of young and middle-aged participants with serious chronic illness, it was easy to recognize the description of the illness as a serious disruptive event, or ‘biographical disruption’, leading to profound rethinking of self-concept [40] (Table 3, II.6; IV.11.; IV.18.). There were also accounts of “loss of self” [41] conceptualized as the crumbling of self-images without the simultaneous development of new ones (Table 3, II.9; IV.16); and chronic illness as an experience of chronic sorrow [42] (Table 3, IV.10).

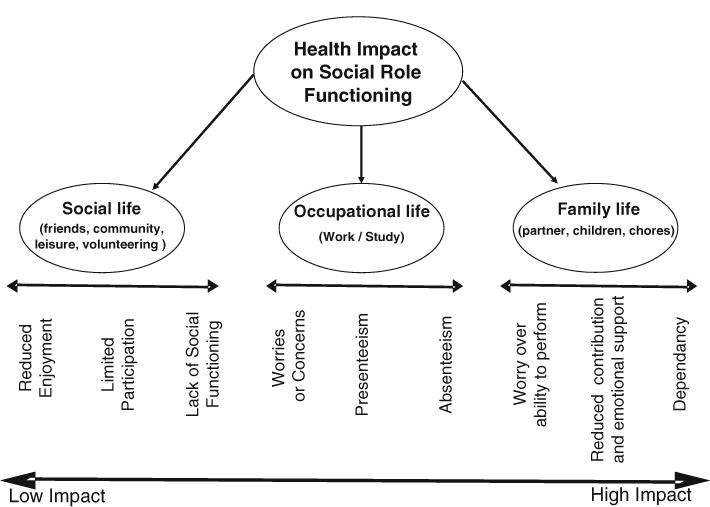

Within this broader focus, the current study had a very specific goal, being to inform the development of a dynamic assessment of role functioning. Based on the results of the discussions, literature review and content review of existing measures [43], a measurement model for the construct of health impact on role functioning was formulated that covers three interrelated but distinct domains of social, occupational and family roles and functioning (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Measurement model of health impact on role functioning

The social domain includes all role activities related to the community, leisure, social life and entertainment. The occupational role domain includes employment roles and activities, as well as the student role. The family domain includes family roles, including the role of a partner as well as household chores and activities. The discussions suggested that health problems affect all roles and that there is a relationship between all domains. The lower levels of impact are related primarily to emotional outcomes, such as reduced enjoyment of social life and worries and concerns about work productivity and/or family. The average level of impact is characterized by declining functioning ability and limited participation in social roles. In the most severe levels of impact, health problems lead to loss of roles in the social and occupational domain and a sense of a dependent position in the family.

The literature and existing measures also support the importance of the model domains—over 40 generic measures were identified assessing one or a combination of these domains. Other qualitative studies aiming to develop HRQOL measures also indirectly support this model. In a focus group study with 21 participants suffering from asthma, participants described the negative effect that asthma has on their social activities, family life and roles, leisure and work [44, 45]. In another focus group study with chronic kidney disease sufferers (n = 40), participants reported that the disease impacted their professional lives and ability to work; affected their relationships with friends and family; caused the loss of family roles and their ability to act as a provider and/or parent in the family; resulted in the weakening and loss of friendships [46, 47].

Strong support for the three dimensional model comes also from the content validation of the social-health domain through focus group study (n = 25) within PROMIS [28]. The study aimed to validate a conceptual model of social participation derived from the ICF, literature review and expert panel consensus. The final PROMIS model defined two subcategories of social role participation—performance and satisfaction in three social contexts—Family/Friend, Work/School and Leisure Activities. Group discussions supported this model. The PROMIS approach is close to our approach, but differs in several aspects: (a) we aim to assess an actual role functioning rather than satisfaction with role performance, (b) we utilize an explicit model for change in roles across life-span, (c) we use specific health attributions in the wording of the items to focus on role limitations caused by health problems and (d) the “friend role” was included in the family domain in the PROMIS model, while we consider it to be part of the social life context.

Limitations

Some of the limitations of this study are inherent to the use of a qualitative focus group approach and are related to the sample recruitment method, number of data collection time points, generalizability and group dynamics [48]. We used a convenience sample, which limits the generalizability of findings and could have resulted in some selection bias, leaving out participants who had too severe limitations to allow their attendance of a focus group. In addition, the study design did not allow us to include participants with a larger variety of conditions. Further qualitative research in samples with other health conditions would strengthen the content validity of the final bank. We tried to capture the impact of health status on role functioning across the lifespan by stratifying our groups by age and including in the discussion questions on retrospective experiences and future expectations. A longitudinal approach with several data collection time points could have resulted in richer and more accurate accounts, but was not feasible. Group dynamics could also lead to study limitations when one person dominates the discussion or participants get influenced by the opinions of other group members. For this study specifically, the use of this “public” forum may have restricted their comments pertaining to the real impact of health status on role functioning. Finally, we also conducted a brief cognitive testing task. While we tried to formulate very specific research questions for this part of the discussions, referring more to perceptions and preferences, the presence of other people in the room may have inhibited participants from sharing problems in understanding items and criticizing presented samples. One-on-one cognitive interviews have the potential to provide more in-depth information and are recommended as a useful evaluation tool in later stages of the testing of the assessment.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by Award Number 1K01AG028760-01A1 from the National Institute on Aging. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Aging or the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Milena D. Anatchkova, Email: Milena.Anatchkova@umassmed.edu, Department of Quantitative Health Sciences, University of Massachusetts Medical School, 55 Lake Ave North, Worcester, MA 01655, USA.

Jakob B. Bjorner, National Research Center for the Working Environment, Copenhagen, Denmark, Quality Metric Incorporated, Lincoln, RI, USA

References

- 1.Biddle BJ. Recent development in role theory. Annual Review of Sociology. 1986;12:67–92. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conway ME. Theoretical approaches to the study of roles. In: Hardy ME, Cook K, editors. Role theory perspectives for health professionals. Norwalk: Appleton & Lange; 1988. pp. 63–73. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hardy ME, Hardy W. Development of scientific knowledge. In: Hardy ME, Conway ME, editors. Role theory: Perspectives for health professionals. Norwalk: Appleton & Lange; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiersma D. Role functioning as a component of quality of life in mental disorders. In: Hardy ME, Conway ME, editors. Role theory: Perspectives for health professionals. Norwalk: Appleton &Lange; 1988. pp. 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sherbourne DC, Stewart AL, Wells KB. Role functioning measures. In: Stewart A, Ware JE Jr, editors. Measuring functioning and well-being. Durham and London: Duke University Press; 1992. pp. 205–219. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. Towards a common language for functioning, disability and health: ICF—The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO); 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ustun TB, Chatterji S, Bickenbach J, Kostanjsek N, Schneider M. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: A new tool for understanding disability and health. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2003;25:565–571. doi: 10.1080/0963828031000137063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Badley EM. Enhancing the conceptual clarity of the activity and participation components of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health. Social Science and Medicine. 2008;66:2335–2345. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perenboom RJ, Chorus AM. Measuring participation according to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) Disability and Rehabilitation. 2003;25:577–587. doi: 10.1080/0963828031000137081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schuntermann MF. The implementation of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health in Germany: Experiences and problems. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research. 2005;28:93–102. doi: 10.1097/00004356-200506000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jette AM. Toward a common language for function, disability, and health. Physical Therapy. 2006;86:726–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mangen DJ, Peterson WA. Social roles and social participation. In: Mangen DJ, Peterson WA, editors. Research instruments in social gerontology. Vol. 2. Minneapolis, MI: University of Minnesota Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Testa MA, Simonson DC. Assessment of quality-of-life outcomes. New England Journal of Medicine. 1996;334:835–840. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603283341306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graney MJ. Social participation roles. In: Mangen DJ, Peterson WA, editors. Social roles and social participation. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press; 1982. pp. 9–42. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cardol M, Brandsma JW, de Groot IJ, van den Bos GA, de Haan RJ, de Jong BA. Handicap questionnaires: What do they assess? Disability and Rehabilitation. 1999;21:97–105. doi: 10.1080/096382899297819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dijkers MP, Whiteneck G, El Jaroudi R. Measures of social outcomes in disability research. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2000;81:S63–S80. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2000.20627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hardy ME, Conway ME. Role theory: Perspectives for health professionals. 2. Norwalk, CT: Appleton & Lange; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDowell I. Measuring health: A guide to rating scales and questionnaires. 2. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loeppke R, Hymel PA, Lofland JH, Pizzi LT, Konicki DL, Anstadt GW, et al. Health-related workplace productivity measurement: General and migraine-specific recommendations from the ACOEM Expert Panel. Journal of Occupation and Environmental Medicine. 2003;45:349–359. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000063619.37065.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lofland JH, Pizzi L, Frick KD. A review of health-related workplace productivity loss instruments. Pharmacoeconomics. 2004;22:165–184. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200422030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mattke S, Balakrishnan A, Bergamo G, Newberry SJ. A review of methods to measure health-related productivity loss. The American Journal of Managed Care. 2007;13:211–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ware JE, Jr, Dewey J. How to score version two of the SF-36 health survey. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Incorporated; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goodman SH, Sewell DR, Cooley EL, Leavitt N. Assessing levels of adaptive functioning: The role functioning scale. Community Mental Health Journal. 1993;29:119–131. doi: 10.1007/BF00756338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gandek B, Sinclair SJ, Jette AM, Ware JE., Jr Development and initial psychometric evaluation of the participation measure for post-acute care (PM-PAC) American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2007;86:57–71. doi: 10.1097/01.phm.0000233200.43822.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haley SM, Gandek B, Siebens H, Black-Schaffer RM, Sinclair SJ, Tao W, et al. Computerized adaptive testing for follow-up after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation: II. Participation outcomes. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2008;89:275–283. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.08.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mulcahey MJ, Haley SM, Duffy T, Pengsheng N, Betz RR. Measuring physical functioning in children with spinal impairments with computerized adaptive testing. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics. 2008;28:330–335. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e318168c792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilkie DJ, Judge MK, Berry DL, Dell J, Zong S, Gilespie R. Usability of a computerized PAINReportIt in the general public with pain and people with cancer pain. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2003;25:213–224. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00638-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Castel LD, Williams KA, Bosworth HB, Eisen SV, Hahn EA, Irwin DE, et al. Content validity in the PROMIS social-health domain: A qualitative analysis of focus-group data. Quality of Life Research. 2008;17:737–749. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9352-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wainer H, Mislevy RJ. Item response theory, item calibration, and proficiency estimation. In: Wainer H, Dorans NJ, Flaugher R, Green BF, Mislevy L, Steinberg L, Thissen D, editors. Computerized adaptive testing: A primer. NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2000. pp. 61–101. [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Brien K. Using focus groups to develop health surveys: An example from research on social relationships and AIDS-preventive behavior. Health Education & Behavior. 1993;20:361–372. doi: 10.1177/109019819302000307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koopman W. Needs assessment of persons with multiple sclerosis and significant others: Using the literature review and focus groups for preliminary survey questionnaire development. Axone. 2003;24:10–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McLeod PJ, Meagher TW, Steinert Y, Boudreau D. Using focus groups to design a valid questionnaire. Academic Medicine. 2000;75:671. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200006000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Detmar SB, Bruil J, Ravens-Sieberer U, Gosch A, Bisegger C. The use of focus groups in the development of the KIDSCREEN HRQL questionnaire. Quality of Life Research. 2006;15:1345–1353. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-0022-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barr J, Schumacher G. Using focus groups to determine what constitutes quality of life in clients receiving medical nutrition therapy: First steps in the development of a nutrition quality-of-life survey. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2003;103:844–851. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(03)00385-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mangione CM, Berry S, Spritzer K, Janz NK, Klein R, Owsley C, et al. Identifying the content area for the 51-item National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire: Results from focus groups with visually impaired persons. Archives of Ophthalmology. 1998;116:227–233. doi: 10.1001/archopht.116.2.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.US Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DeWalt DA, Rothrock N, Yount S, Stone AA. Evaluation of item candidates: The PROMIS qualitative item review. Medical Care. 2007;45:S12–S21. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000254567.79743.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thorne S, Jensen L, Kearney MH, Noblit G, Sandelowski M. Qualitative metasynthesis: Reflections on methodological orientation and ideological agenda. Qualitative Health Research. 2004;14:1342–1365. doi: 10.1177/1049732304269888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lawton J. Lay experiences of health and illness: Past research and future agendas. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2003;25:23–40. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.00338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bury M. Chronic illness as biographical disruption. Sociology of Health & Illness. 1982;4:167–182. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.ep11339939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Charmaz K. Loss of self: A fundamental form of suffering in the chronically ill. Sociology of Health & Illness. 1983;5:168–195. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.ep10491512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hainsworth MA. Living with multiple sclerosis: The experience of chronic sorrow. The Journal of Neuroscience Nursing. 1994;26:237–240. doi: 10.1097/01376517-199408000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anatchkova MD, Bjorner JB. Internal report. 2007. Conceptual Review of Role Functioing Measures. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Turner-Bowker DM, Saris-Baglama RN, DeRosa M, Paulsen CA, Bransfield C. Participants’ experience of asthma: Results from a Focus Group Study; Poster presented at the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research, 13th Annual International Meeting; Toronto, Canada. In. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Turner-Bowker DM, Saris-Baglama RN, DeRosa MA, Paulsen CA, Bransfield CP. The Patient: Patient-Centered Outcomes Research. 2009. Using qualitative research to inform the development of a comprehensive outcomes assessment for asthma. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Richardson MM, Saris-Baglama RN, Anatchkova MD, Stevens LA, Miskulin DC, Turner-Bowker DM, et al. Patient experience of chronic kidney disease (CKD): Results of a Focus Group Study. 2007 In. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Billson J, Steinmeyer M, Reis K, Downes B. Technical report prepared for Quality Metric Incorporated: Group Dimensions International. 2007. The impacts of chronic kidney disease on quality of life: Focus group exploration of domains/items for computerized adaptive testing. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Conrad P. Qualitative research on chronic illness: A commentary on method and conceptual development. Social Science and Medicine. 1990;30:1257–1263. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90266-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]