Abstract

Heterochromatin assembly and its associated phenotype, position effect variegation (PEV), provide an informative system to study chromatin structure and genome packaging. In the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, the Y chromosome is entirely heterochromatic in all cell types except the male germline; as such, Y chromosome dosage is a potent modifier of PEV. However, neither Y heterochromatin composition, nor its assembly, has been carefully studied. Here, we report the mapping and characterization of eight reporter lines that show male-specific PEV. In all eight cases, the reporter insertion sites lie in the telomeric transposon array (HeT-A and TART-B2 homologous repeats) of the Y chromosome short arm (Ys). Investigations of the impact on the PEV phenotype of mutations in known heterochromatin proteins (i.e., modifiers of PEV) show that this Ys telomeric region is a unique heterochromatin domain: it displays sensitivity to mutations in HP1a, EGG and SU(VAR)3-9, but no sensitivity to Su(z)2 mutations. It appears that the endo-siRNA pathway plays a major targeting role for this domain. Interestingly, an ectopic copy of 1360 is sufficient to induce a piRNA targeting mechanism to further enhance silencing of a reporter cytologically localized to the Ys telomere. These results demonstrate the diversity of heterochromatin domains, and the corresponding variation in potential targeting mechanisms.

Introduction

Heterochromatin represents a unique type of chromatin structure that confers transcriptional silencing by regular packaging of distinct domains enriched for repetitious DNA [1]. Abnormalities in the formation and/or maintenance of heterochromatin therefore are commonly associated with transposon activation and genome instability [2]. Heterochromatin also plays an important role in cell division; as part of the centromeric structure, heterochromatin is required for proper segregation of chromosomes during mitosis [3]. Other regulatory roles of heterochromatin, such as telomere length homeostasis [4], and proper expression of heterochromatic genes [5], have also been documented.

The Position Effect Variegation (PEV) phenotype, commonly monitored in the adult fly eye, has been used in many previous studies as an indicator of the degree of heterochromatin formation at the underlying locus [6]. PEV results from positioning a euchromatic reporter gene in or close to a heterochromatic environment by transposition or rearrangement. Several lines of evidence indicate that the spreading of heterochromatin packaging into the promoter region of the euchromatic gene is the cause of transcriptional silencing [7]. Silencing of the underlying euchromatic gene occurs in some but not all cells in a population, giving rise to a variegating phenotype; this differential spreading of heterochromatin is suggested to be a stochastic process [8]. The extent of silencing (variegation) can serve as a proxy for the extent of heterochromatin formation at the particular locus. A mutation that impacts the level of PEV is therefore indicative of a gene that functions in the formation and/or maintenance of heterochromatin [9]. Identification of mutations resulting in strong suppression of PEV (loss of silencing) and molecular characterization of these Su(var) loci has laid the groundwork for understanding heterochromatin formation in flies [10], [11]. Genes such as Su(var)3-9 (a histone H3K9 methyltransferase) and Su(var)3-3 (an H3K4 demethylase), identified and characterized under this paradigm, have revealed much of what we know about this alternative chromatin state [6].

PEV has been used as an assay to probe the heterochromatic landscape of the genome [12]. A P-element harboring an hsp70-white reporter gene was mobilized in the fly genome to identify heterochromatic regions, those that induce a variegating eye phenotype [12]. This screen recovered lines with insertions into pericentric domains, telomere associated satellite-like (TAS) regions, the fourth chromosome and the Y chromosome, as anticipated from prior cytogenetic analysis. Thus it produced PEV reporter lines that can be used to monitor the structure of heterochromatin across the genome. Use of these lines quickly established that not all heterochromatin has the same composition; different domains show distinct responses to different Su(var) mutations [13], [14]. Based on the differential response profile to well-known suppressors of variegation (as well as other evidence), a major distinction has been made between pericentric and telomeric heterochromatin, suggesting that different assemblies and silencing mechanisms are involved [15]. In particular, telomere position effect (TPE; studied using reporters in the subtelomeric TAS elements) is inert to mutations in Su(var)205 (which codes for HP1a) but is suppressed by mutations in Su(z)2 (a component of the Pc system) [13], [15], while the opposite is true for pericentric PEV. Further analyses have revealed additional unique domains of heterochromatin in the genome. For example, fourth chromosome PEV is not generally suppressed by mutations in Su(var)3-9 [14], but is sensitive to mutations in egg, indicating that a different histone methyltransferase (HMT) is required for silencing [16]–[18]. Additional analyses of this type are likely to reveal more distinct types of heterochromatin, presumably reflecting differences in the underlying DNA repeat sequences and their organization.

The question of how different types of heterochromatin are established in the genome remains an active area of research. Different targeting mechanisms could be utilized for different types of heterochromatic domains. In flies, both the piRNA pathway and the endo-siRNA pathway have been implicated in targeting heterochromatin formation [19]–[21]. While these studies provide evidence supporting a small RNA targeting model for heterochromatin formation at some repetitious elements, given the diversity of heterochromatin domains, one can also anticipate a diversity of targeting mechanisms.

In flies, the Y chromosome has long been known to be a largely heterochromatic domain. In fact, Y chromosome dosage was one of the first modifiers of PEV to be identified [22]. The Y has been described as a ‘sink’ for components essential for heterochromatin formation and/or maintenance. It appears that additional copies of the Y chromosome impact PEV at other loci in the genome by competing for a limited amount of shared key factors required for heterochromatin integrity [23], [24]. Polymorphisms in the Y-linked rDNA loci have also been shown to modulate the heterochromatic landscape of the genome [25]. Recently, reports from Hartl and colleagues have further elaborated on how polymorphisms in Y chromosome heterochromatin can impact chromatin-based regulatory processes in other regions of the genome [26]–[28]. However, relatively little is known about the formation/maintenance of heterochromatin on the Y chromosome itself. A paucity of PEV reporter lines for the Y chromosome is one of the major obstacles in studying the mechanisms involved in heterochromatin formation and maintenance within this domain.

Over the past decade, we have collected eight variegating lines exhibiting a male-specific PEV phenotype. Here we map the insertion sites of these eight lines to the telomeric transposon array (HeT-A and TART-B2 repeats) of Ys (short arm of the Y chromosome). We further characterize the heterochromatic properties of this region by examining the impact of mutations in PEV modifiers on these reporters. This telomeric Ys heterochromatin shows a unique response profile compared to other parts of the genome; nonetheless, our studies suggest that some of the mechanisms for heterochromatin formation and maintenance are shared among the Y chromosome, pericentric, and 4th chromosome heterochromatins. While it appears that the endo-siRNA pathway is likely the major mechanism used to target heterochromatin formation at this domain, an ectopic copy of the 1360 transposon remnant is sufficient to drive a piRNA-dependent heterochromatin targeting mechanism to further enhance silencing of a reporter cytologically localized to the Ys telomere. We conclude that the Ys telomeric region is a unique domain of heterochromatin. Further investigation of this region will be informative in understanding chromatin packaging in general.

Results

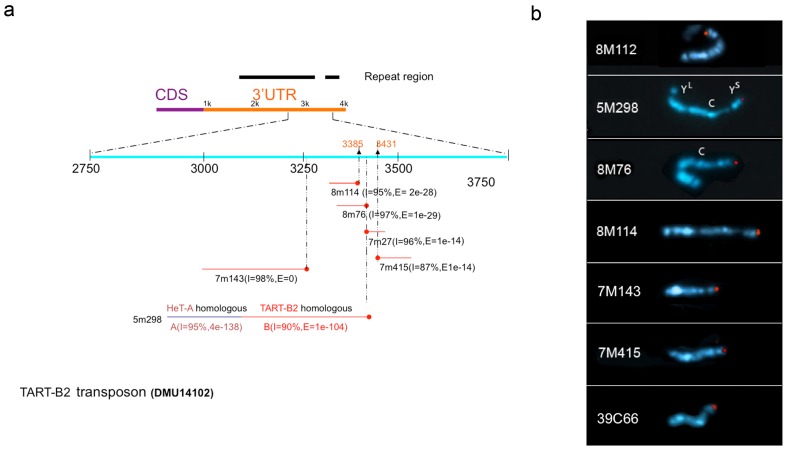

To precisely locate the insertion sites of the Y-linked PEV reporters, we performed inverse PCR followed by sequencing. While we cannot precisely map the location of each insert using BLASTN against the entire genome assembly, we can nonetheless map the insertion sites for all eight Y-linked reporter lines to internal regions of the telomeric retrotransposons. In six of these lines the reporter element is inserted into a TART-B2 element, while in the other two lines (39C66 and 8M112) the reporter is inserted into a HeT-A element (HeT-A subfamily D and HeT-A to HeT-A Junction respectively). Surprisingly, all six reporters inserted into the TART-B2 element are located in the 3′-UTR of the element, with five of them clustered within a 50 nts range when mapped back to a TART-B2 consensus sequence (Fig. 1a). Because there are multiple copies of TART-B2 elements on the Y chromosome, and the quality of this region of the published assembly is relatively poor, we cannot resolve in which TART-B2 elements these insertions reside. However, a comparison of the flanking sequences among the six insertion lines identifies sequence polymorphisms, which suggests that the inserts are in different copies of TART-B2. This result suggests that there is a common region in the TART-B2 3′UTR that is a particular hotspot for P-element insertions, consistent with results previously described by Mason and colleagues [29].

Figure 1. Sequencing and in situ hybridization mapping locate the Y-linked PEV reporters in the telomeric transposon arrays of Ys.

(a) Alignment of reporter insertion flanking sequences to a consensus sequence of telomeric retro-transposon TART-B2. The 1 Kb region in the 3′-UTR harboring the insertion sites is magnified. The effective sequence read length for each reporter line is represented by the red line aligned to the region. The red dot at the end of each red line indicates the 5′ end of the reporter. The reporter flanking sequence of line 5m298 starts in the 3′ end of a TART-B2 element and extends upstream to a neighboring HeT-A element, suggesting insertion into a partial fragment of TART. (b) In situ hybridization images of the metaphase chromosomes from third instar larval brain squashes. Only the Y chromosome of the representative metaphase spread is shown. DAPI staining is pseudo-colored in blue and the hybridization signal is in red. (C: centromere, YL: long arm, YS: short arm).

HeT-A and TART elements are distributed throughout telomeric and pericentric regions of the Y chromosome [30]. To further distinguish between these potential insertion sites, we performed in situ hybridization on metaphase chromosomes using the reporter sequence as a probe. Interestingly, we found that in all eight lines the reporter is inserted at the tip of Ys (Fig. 1b). These observations allow us to conclude that all eight reporter lines characterized here have an insert in the telomeric terminal retrotransposon array of Ys. The cytological results are consistent with the molecular mapping results presented above – both indicate that this region of the Y chromosome is relatively accessible to P element insertions (Fig. 1). It should be noted that reporters inserted into the terminal retrotransposon array of HeT-A, TAHRE, and TART have been previously described for the major autosomes [29]. Most of these insertion lines do not show a variegating phenotype unless the reporter is located close to the TAS region [29]. We therefore infer that our variegating reporters likely reflect the results of a competition between the spreading of adjacent heterochromatin and the expression of these retrotransposons, which has created a unique heterochromatic domain.

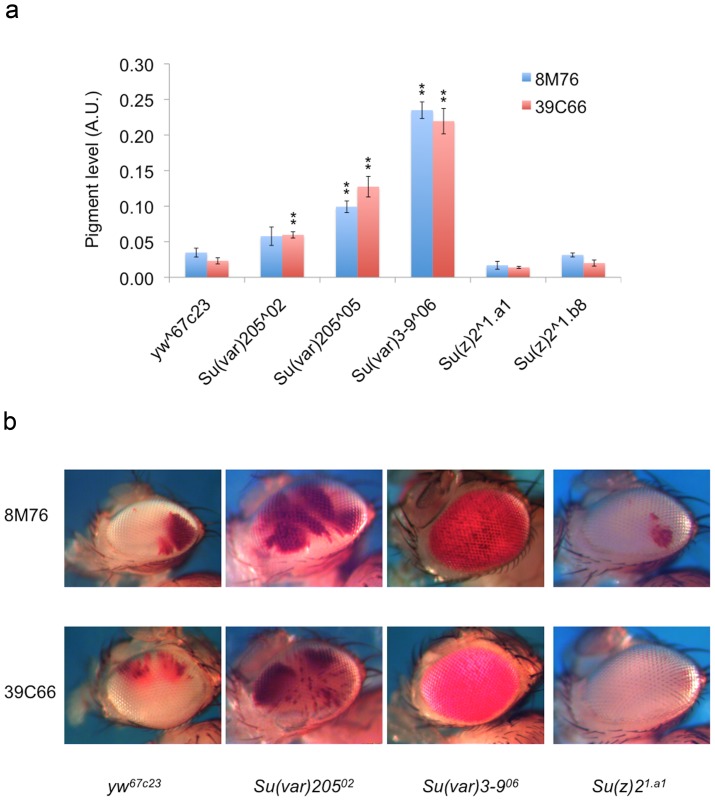

These variegating reporter lines present a new opportunity to elucidate the chromatin structure at a telomere of the Y chromosome. We first looked at the response of these variegating reporters to well-characterized modifiers of PEV and TPE (Fig. 2). Given that all of these reporter lines carry inserts in the HeT-A and TART elements of Ys, we chose two lines, 39C66 (a HeT-A insert) and 8M76 (a TART insert), as representatives of this set for further analysis. We first tested dominant effects of mutations in modifiers of TPE. Multiple alleles of Su(z)2, a transcription factor, have previously been shown to significantly suppress TPE of TAS inserts [13], [15]. However, no obvious suppression effects were observed for both of the alleles tested here (Fig. 2a, b), suggesting that the telomeric retrotransposon region of Ys does not have the chromatin structure typical for the TAS telomere-associated arrays, which are immediately upstream of HeT-A and TART arrays in the autosomes. We next examined the impact of a classic PEV suppressor, Su(var)205, on these reporters. Su(var)205 encodes a chromo-domain containing protein, HP1a, which is implicated in the formation and spreading of heterochromatin [31]–[33]. Despite the known role of HP1a in telomere capping [34], [35], mutations in Su(var)205 do not appear to modify TPE as seen using lines with the reporter inserted in TAS [13]. Interestingly, despite the fact that these inserts are found in the telomeric region, both Su(var)205 alleles tested here show significant dominant suppression of variegation for both reporters (Fig. 2a, b). These observations suggest a response profile for the Ys HeT-A/TART telomeric heterochromatin that is more similar to PEV than TPE. We next tested the impact of an insertion mutation of Su(var)3-9. The Su(var)3-906 allele disrupts the production of the SU(VAR)3-9 protein [36] and has been shown to impact both TPE and PEV [15]. Strong dominant suppression of variegation is observed with this allele for these Y-linked reporters (Fig. 2a, b), indicating an important role for this gene product in the chromatin structure at this region.

Figure 2. Response of Y-linked PEV reporter lines to mutations in well-known modifiers of PEV and TPE (dominant effects).

(a) Pigment level quantification representing the level of PEV. Progeny from a cross with yw67c23 is used as the wild type control. The allele used in each cross is shown on the X-axis. (Bars represent the average pigment level ± standard error. Asterisks are used to indicate mutant alleles that show statistically significant modifier activities, single, p<0.05; double, p<0.005.) (b) Representative pictures showing the dominant impact of the mutations on the fly eyes. The allele used for each modifier is listed below each column. The reporter line used is shown to the left of each row.

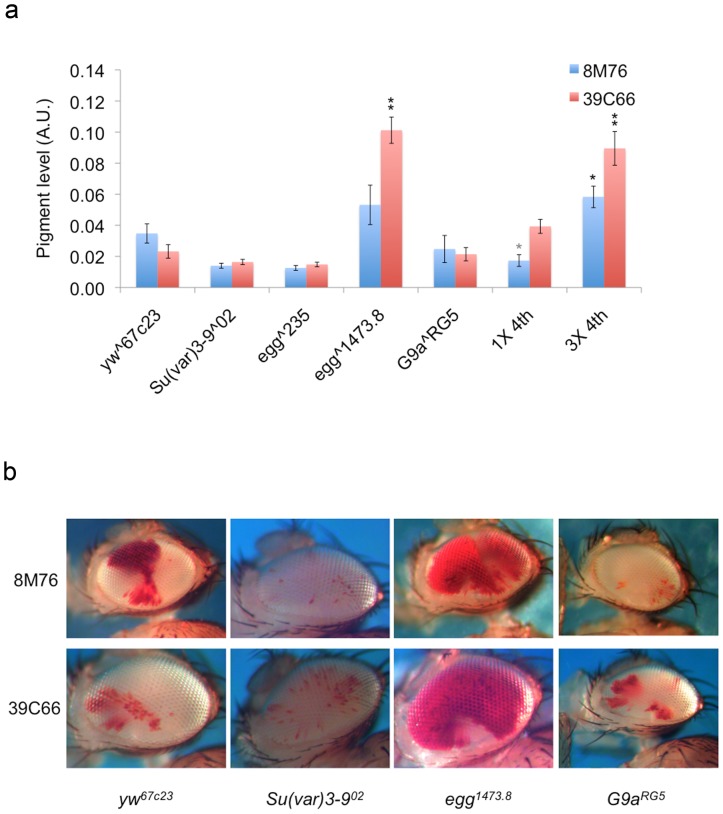

SU(VAR)3-9 is a histone 3 lysine 9 methyl-transferase. Given the strong impact of the Su(var)3-906 allele on variegation, we reasoned that SU(VAR)3-9 might function through its enzymatic activity to modify the chromatin structure at this region. However, an allele disrupting the enzymatic activity of SU(VAR)3-9 [36], Su(var)3-902, did not show a suppression of variegation (Fig. 3a, b). This suggests that the critical function of SU(VAR)3-9 in this region is structural rather than enzymatic. This interpretation is supported by previous results documenting the antipodal effect of SU(VAR)3-9 on PEV [23]. Our observations lead us to infer that SU(VAR)3-9 is likely not the HMT functioning in the Ys telomeric heterochromatin.

Figure 3. Impact of mutations in HMTs and of dosage of the 4th chromosome on the level of variegation of the Y-linked reporters.

(a) Pigment level quantification showing the level of expression. (Bars represent the average pigment level ± standard error. Asterisks are used to indicate mutant alleles that show statistical significant modifier activities, single, p<0.05; double, p<0.005.) 1X 4th and 3X 4th represent the copy number of the 4th chromosome in the assayed flies. Note that the control line yw67C23 has 2X 4th (See Table S1 for information on the fly lines used.), the t test on 1X 4th examines E(var) activities of the allele (see materials and methods for details). (b) Representative pictures showing the dominant impacts on PEV in the fly eye from mutations disrupting HMT activities.

To identify the potential HMTs functioning at this region, we looked for effects from mutations in the genes for other known H3K9 HMTs. In addition to Su(var)3-9, two more genes, egg and G9a, have been identified in the fly genome as potential H3K9 HMTs [18], [37]–[39]. Dominant effects of mutations in egg and a recessive effect of G9a were tested for their impact on the variegation phenotype of these reporters. Only the egg1473.8 allele shows a strong suppression of variegation at these sites, consistent with the interpretation that EGG is the major HMT functioning in the formation/maintenance of heterochromatin at the Ys telomeric region. The two egg alleles tested show different effects on the suppression of variegation. The egg1473.8 allele is a deletion of the entire SET domain, a domain which is required for the HMT activity of EGG [40]. In contrast, the egg235 allele has a di-nucleotide substitution that creates a cryptic splice site for the 4th intron [40]. Retention of this intron will introduce a premature stop codon that results in a protein product with no identifiable functional domains. However, a cryptic splice site actually allows normal splicing to occur at a low frequency, which results in the production of some wild type protein [40]. The comparison on the impact from the two egg alleles therefore represents a comparison between a dominant effect of the SET domain deletion and an incomplete null mutation. We interpret the discrepancy between the two alleles in their impact on variegation as an additional piece of evidence demonstrating the importance of the HMT activity of EGG in this region.

EGG has previously been characterized as a 4th chromosome-specific HMT [16]–[18]. It is also known to impact expression from some reporters in the pericentric heterochromatin [17]. Nonetheless, the observations above suggest that the 4th chromosome and Ys telomeric heterochromatin share common components for heterochromatin formation or maintenance. To test this hypothesis, we took advantage of the attached 4th chromosome line [14] to generate flies with only one copy or with three copies of the 4th chromosome to examine the impact of dosage on Ys telomeric heterochromatin. Increasing heterochromatic mass of a particular type in the genome could lead to increased competition for the available components for heterochromatin formation/maintenance [23]. On increasing dosage of the 4th chromosome, we do observe a suppression of variegation for the Y-linked reporters (Fig. 3a), whereas previous studies have found no effect of 4th chromosome dosage on reporters in either the pericentric or telomeric (TAS) regions of the 2nd chromosome [14]. Earlier studies have shown that Y chromosome dosage does have a similar impact on fourth chromosome reporters [12]. These observations reinforce the conclusion that the 4th chromosome and the Ys telomeric heterochromatin share some unique components for heterochromatin formation and/or maintenance.

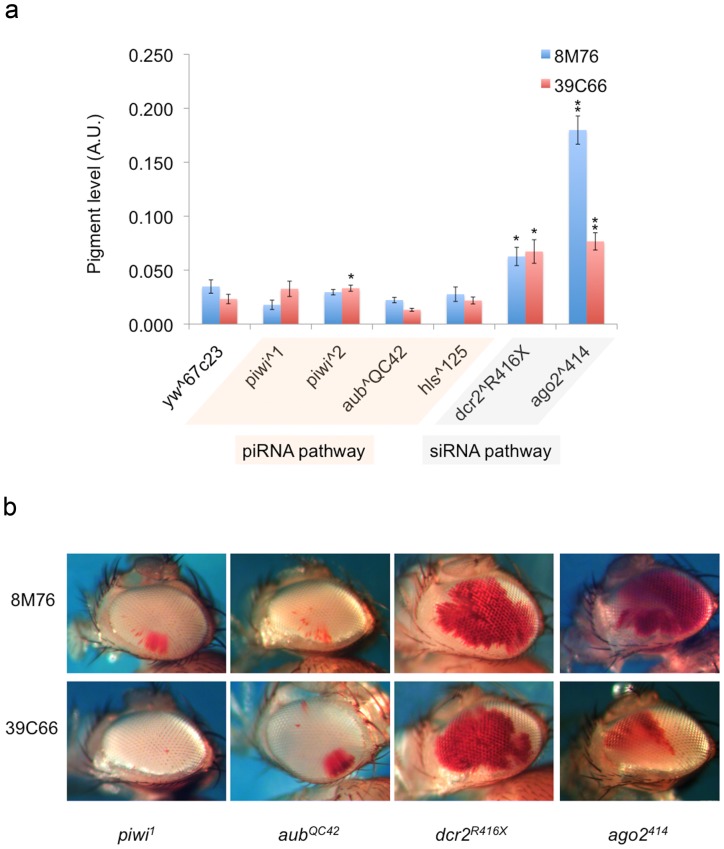

Small RNA targeting mechanisms have been demonstrated to be one of the major mechanisms for initiating the formation of heterochromatin in the fission yeast S. pombe [41]–[43]. In the fruit fly, both siRNA and piRNA systems have been implicated in this process [19]–[21]. To ask whether small RNA targeting of heterochromatin formation could participate in the formation of Ys telomeric heterochromatin, we examined the impacts of dominant mutations in both siRNA and piRNA pathways. No obvious impact is observed when mutations in components of the piRNA pathway are introduced (Fig. 4a, b). We examined the impacts of piwi1, piwi2, aubQC42 and hls125 mutations on the variegation of the Ys telomeric reporters, and no obvious suppression effects were observed, although there may be a weak effect of the piwi2 allele on 39C66 (Fig. 4a). In contrast, both mutations in the siRNA pathway that were tested strongly suppress variegation of these reporters (Fig. 4a,b), indicating an involvement of this pathway in the heterochromatin silencing of the Ys chromosome. Dcr-2R416X has a point mutation that truncates the protein produced and disrupts its function in producing siRNA [44]. ago2414 is a loss of function allele with its second exon deleted by imprecise excision [45]. That mutations in the siRNA pathway dominantly suppress variegation indicates a role for siRNA in targeting heterochromatin formation in this region.

Figure 4. Impacts of mutations in components of the small RNA pathways on the level of variegation of the Y-linked reporters.

(a) Pigment level quantification indicating the extent of the suppression of PEV. (Bars represent the average pigment level ± standard error. Asterisks are used to indicate mutant alleles that show statistical significant modifier activities, single, p<0.05; double, p<0.005.) Pathways requiring the genes tested are indicated below the allele names. (b) Representative pictures showing the dominant impacts on PEV in the fly eye from mutations disrupting small RNA pathways.

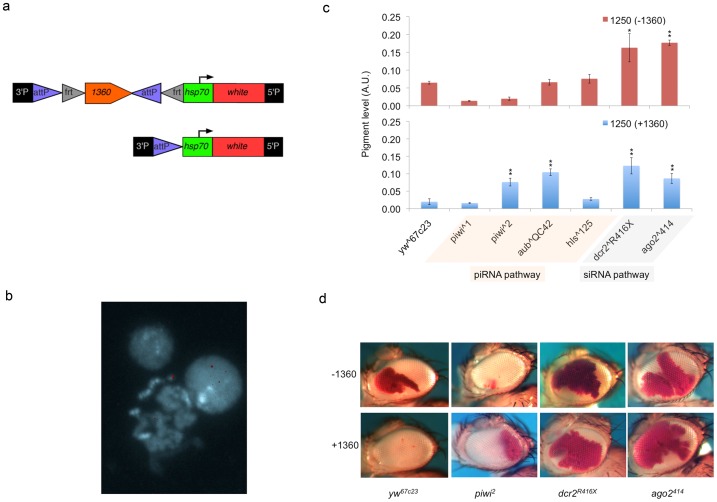

Transposon density, particularly that of the 1360 DNA transposon, has been shown to be correlated with heterochromatin silencing on the 4th chromosome [46]. Previously we have shown that introducing an extra copy of 1360 can enhance the variegation phenotype of a reporter in regions sensitive to mutations in small RNA pathways [47]. In an independent screen using a P element containing a copy of 1360 upstream of the hsp70-white reporter (Fig. 5a), we recovered an additional Y-linked PEV line, line 1250 [48]. The 1360 element in this construct is flanked by FRT sites, which allows FLP-mediated excision to test its impact on PEV (Fig. 5a). We were unable to precisely map the insertion site of line 1250 using inverse PCR sequencing. However, in situ hybridization experiments map the insertion site again in the telomeric region of Ys (Fig. 5b). Reporter line 1250 therefore provides an opportunity to examine the sensitivity of variegation in the Ys telomeric region to an ectopic 1360 element. FLP-mediated excision of the 1360 element resulted in strong suppression of variegation at this locus (Fig. 5c, d; yw67c23, compare +1360 with −1360), consistent with the interpretation that the exogenous 1360 element plays an important role in promoting local heterochromatin structure. We next investigated the potential mechanism of this 1360-dependent enhancement of heterochromatin silencing. We examined the impact of mutations in the siRNA and piRNA pathways on the variegation phenotype in reporter lines 1250 with and without the extra copy of the 1360 element. In the absence of the extra 1360 element, the reporter line 1250 shows similar responses to mutations in components of the small RNA pathways as seen for the other lines tested in this study (compare Fig. 4a, 5c). Interestingly, with the ectopic copy of 1360 element present, the same reporter appears to show dominant suppression of variegation in response to mutations of piwi and aub (Fig. 5c). This suggests that the enhancement of variegation resulting from the extra copy of the 1360 element is operating via a piRNA dependent targeting mechanism. We therefore conclude that the ectopic copy of the 1360 element at the Ys telomeric region is sufficient to recruit the piRNA-dependent targeting machinery to enhance heterochromatin silencing in a region that is normally dependent on the siRNA pathway for heterochromatin targeting.

Figure 5. An ectopic 1360 element enhances Ys telomeric PEV via a piRNA-dependent mechanism.

(a) Diagram showing the construct used in this line. FRT sites (gray triangles) flanking the ectopic copy of the 1360 element allow a FLPase mediated excision of the element. (b) In situ hybridization image of metaphase chromosomes of line 1250. The DAPI staining is pseudo-colored in blue and the hybridization signal in red. (c) Pigment level quantification comparing the impact on reporter expression of mutations in different small RNA pathway components with and without the ectopic copy of the 1360 element in the reporter. (Bars represent the average pigment level ± standard error. Asterisks are used to indicate mutant alleles that show statistical significant modifier activities, single, p<0.05; double, p<0.005.) (d) Representative pictures comparing dominant impacts on PEV in the fly eye from mutations disrupting small RNA pathways, with (+) and without (−) the ectopic copy of the1360 element in the reporter.

Discussion

Despite being one of the first heterochromatic regions in the fly genome to be identified, the packaging of Y chromosome is not well understood. The poor quality of the sequence assembly in this region of the fly genome severely restricts our ability to perform a comprehensive survey of its chromatin landscape. Reporter insertion lines that can be uniquely mapped by in situ hybridization therefore present unique opportunities to explore the chromatin packaging of this region.

Screens using a P element carrying an hsp70-white reporter have led to the recovery of variegating lines with an insertion into the HeT-A/TART arrays at the Ys telomere. This is surprising, in that the HeT-A/TART retrotransposons are know to be expressed, and prior studies [29] have reported that insertions into similar telomeric sequences in the autosomes results in full expression of the reporter, unless the reporter is positioned close to the proximal TAS arrays, which are silenced. We have analyzed the impacts on the observed PEV phenotype of our Ys telomere reporters resulting from mutations in PEV modifiers that are well characterized. We have found that these reporters do not mimic the TAS-associated TPE reporters seen on the autosomes; instead, the Ys reporters show strong suppression in response to mutations in the gene for HP1a, and no suppression in response to mutations in Su(z)2. In addition, we found that while the chromatin structure at this region is sensitive to the dosage of Su(var)3-9 (in contrast to the 4th chromosome heterochromatin), it actually requires the SET domain of EGG for proper silencing (similar to the 4th chromosome). These results enable us to conclude that the telomeric HeT-A/TART region of Ys is a unique domain of heterochromatin. Whether this reflects a structure uniquely targeted to these Y chromosome HeT-A and TART elements, or the spreading of a heterochromatin structure targeted to other adjacent repetitious elements, cannot be determined given the current information. Regardless, we propose that the Ys telomeric region should be added to the list of distinct subcategories of heterochromatin. While each of these domains has unique characteristics, they nonetheless appear to share certain modifiers and utilize some of the same proteins for heterochromatin formation.

Given the repetitive nature of Y chromosome, we propose a targeting mechanism for its heterochromatin formation that utilizes small RNAs derived from transposable elements. We have found that while reporters in this region normally respond to mutations in the endo-siRNA pathway, an ectopic copy of the1360 element is sufficient to enhance heterochromatic silencing via a piRNA-dependent silencing pathway. This observation again suggests complex cross talk between different mechanisms of heterochromatin targeting/formation. It should be noted, however, that while we were able to map the insertion site for line 1250 to the Ys telomeric region using in situ hybridization, we were unable to align the flanking sequence to any consensus sequence. This observation indicates that the reporter construct for line 1250 is not located within a known transposon, which is in contrast to the rest of the reporter lines tested in this study. The significance of this difference remains to be investigated.

Our identification of an additional type of heterochromatin corroborates the multiple chromatin states models resulting from large-scale genome-wide studies of the distribution of histone modifications and chromosomal proteins, such as modENCODE [49]. As our study demonstrates, while the heterochromatin/euchromatin dichotomy is useful and convenient in describing much of what we know about chromatin structure, it is inadequate in capturing the diversity of chromatin structures within a genome. Future studies on the Y chromosome heterochromatin will likely yield new insights on the process of chromatin packaging and gene regulation.

Materials and Methods

Fly Stocks, Genetics and Husbandry

Fly lines 39C66, 5M298, 7M27, 7M143, 7M415, 8M76, 8M112, 8M114 and 1250, were recovered from transposition-based screens that have been previously reported [12], [48], [50]. Crosses testing for a dominant effect of known Su(var)s were carried out at 25°C, 70% humidity on regular cornmeal sucrose-based medium [51]. In each cross, male flies exhibiting a representative eye phenotype for a given reporter line were crossed to female virgins carrying the specified modifier mutation. The 3X 4th line has one copy of the normal 4th chromosome and one copy of the attached 4th chromosome. More detailed information on modifier lines used is listed in Table S1. Standard balancers are used to maintain the mutation in each stock.

Inverse PCR and Sequencing

Inverse PCR to amplify the region flanking the insertion site was done as previously described [46]. The PRC product was than treated with ExoSAP (Affymetrix) and sequenced using BigDye Terminator v1.1 (Applied Biosystems) following vendor’s instructions. The sequence results were then analyzed using NCBI BLAST with the nr database.

In situ Hybridization

In situ hybridization on metaphase chromosomes from third instar larval neuroblasts was done as previously described [52]. The probe used in this study was the P element reporter containing hsp26-pt and an hsp70-driven white gene [12].

PEV Assay

Ethanol based pigment extraction and quantification was essentially done as previously described [46] with some minor adjustments. The overnight incubation step at 4°C was omitted. To increase the throughput and consistency, a Mixer Mill MM 300 was utilized to homogenize the sample and a plate reader was used for spectroscopy. For each genotype, three to five samples were measured for pigment level; each sample is composed of five male flies (3∼5 days old) randomly selected from the population.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical significance of the impact of a given mutant allele on the PEV eye phenotype was assessed by performing one-sided Welch two-sample t tests for multiple independent samples. In each case [except for the haploid 4th mutant line] the significance of the increase in red pigmentation (suppression of variegation) relative to the yw background was tested at levels of p<0.05 and p<0.005. The Enhancer of variegation [E(var)] activity of the haploid 4th mutant was assessed in the same way, except that a decrease in pigmentation is expected and tested accordingly. All tests were performed with the R statistical programming language [53].

Supporting Information

The genotypes of all fly lines used in this study are shown (middle column), with the source (lab and pertinent reference) given (right-hand column). If the stock is available from the Bloomington Stock Center, the stock number is provided (left-hand column).

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Mary-Lou Pardue and members of the Elgin lab for critical comments on the manuscript, and the Bloomington Stock Center and numerous individual labs for the fly lines.

Funding Statement

This work is supported by Howard A. Schneiderman Fellowship (SHW) and by NIH grant GM068388 (to SCRE). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Elgin SC (1996) Heterochromatin and gene regulation in Drosophila. Curr Opin Genet Dev 6: 193–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Peng JC, Karpen GH (2008) Epigenetic regulation of heterochromatic DNA stability. Curr Opin Genet Dev 18: 204–211 10.1016/j.gde.2008.01.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dalal Y, Furuyama T, Vermaak D, Henikoff S (2007) Structure, dynamics, and evolution of centromeric nucleosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 15974–15981 10.1073/pnas.0707648104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schoeftner S, Blasco MA (2009) A “higher order” of telomere regulation: telomere heterochromatin and telomeric RNAs. EMBO J 28: 2323–2336 10.1038/emboj.2009.197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yasuhara JC, Wakimoto BT (2006) Oxymoron no more: the expanding world of heterochromatic genes. Trends Genet 22: 330–338 10.1016/j.tig.2006.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Girton JR, Johansen KM (2008) Chromatin structure and the regulation of gene expression: the lessons of PEV in Drosophila. Adv Genet 61: 1–43 10.1016/S0065-2660(07)00001-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tartof KD, Hobbs C, Jones M (1984) A structural basis for variegating position effects. Cell 37: 869–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cheutin T, Gorski SA, May KM, Singh PB, Misteli T (2004) In vivo dynamics of Swi6 in yeast: evidence for a stochastic model of heterochromatin. Mol Cell Biol 24: 3157–3167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schotta G, Ebert A, Dorn R, Reuter G (2003) Position-effect variegation and the genetic dissection of chromatin regulation in Drosophila. Semin Cell Dev Biol 14: 67–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wustmann G, Szidonya J, Taubert H, Reuter G (1989) The genetics of position-effect variegation modifying loci in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Gen Genet 217: 520–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Grigliatti T (1991) Position-effect variegation–an assay for nonhistone chromosomal proteins and chromatin assembly and modifying factors. Methods Cell Biol 35: 587–627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wallrath LL, Elgin SC (1995) Position effect variegation in Drosophila is associated with an altered chromatin structure. Genes Dev 9: 1263–1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cryderman DE, Morris EJ, Biessmann H, Elgin SC, Wallrath LL (1999) Silencing at Drosophila telomeres: nuclear organization and chromatin structure play critical roles. EMBO J 18: 3724–3735 10.1093/emboj/18.13.3724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Haynes KA, Gracheva E, Elgin SCR (2007) A Distinct type of heterochromatin within Drosophila melanogaster chromosome 4. Genetics 175: 1539–1542 10.1534/genetics.106.066407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Doheny JG, Mottus R, Grigliatti TA (2008) Telomeric position effect–a third silencing mechanism in eukaryotes. PLoS ONE 3: e3864 10.1371/journal.pone.0003864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tzeng T-Y, Lee C-H, Chan L-W, Shen C-KJ (2007) Epigenetic regulation of the Drosophila chromosome 4 by the histone H3K9 methyltransferase dSETDB1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 12691–12696 10.1073/pnas.0705534104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brower-Toland B, Riddle NC, Jiang H, Huisinga KL, Elgin SCR (2009) Multiple SET methyltransferases are required to maintain normal heterochromatin domains in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 181: 1303–1319 10.1534/genetics.108.100271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Seum C, Reo E, Peng H, Rauscher FJ 3rd, Spierer P, et al. (2007) Drosophila SETDB1 is required for chromosome 4 silencing. PLoS Genet 3: e76 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Brower-Toland B, Findley SD, Jiang L, Liu L, Yin H, et al. (2007) Drosophila PIWI associates with chromatin and interacts directly with HP1a. Genes Dev 21: 2300–2311 10.1101/gad.1564307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fagegaltier D, Bougé AL, Berry B, Poisot E, Sismeiro O, et al. (2009) The endogenous siRNA pathway is involved in heterochromatin formation in Drosophila. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106: 21258–21263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang SH, Elgin SCR (2011) Drosophila Piwi functions downstream of piRNA production mediating a chromatin-based transposon silencing mechanism in female germ line. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 21164–21169 10.1073/pnas.1107892109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gowen JW, Gay EH (1934) Chromosome Constitution and Behavior in Eversporting and Mottling in Drosophila Melanogaster. Genetics 19: 189–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Locke J, Kotarski MA, Tartof KD (1988) Dosage-dependent modifiers of position effect variegation in Drosophila and a mass action model that explains their effect. Genetics 120: 181–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dimitri P, Pisano C (1989) Position effect variegation in Drosophila melanogaster: relationship between suppression effect and the amount of Y chromosome. Genetics 122: 793–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Paredes S, Maggert KA (2009) Ribosomal DNA contributes to global chromatin regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 17829–17834 10.1073/pnas.0906811106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lemos B, Branco AT, Hartl DL (2010) Epigenetic effects of polymorphic Y chromosomes modulate chromatin components, immune response, and sexual conflict. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 15826–15831 10.1073/pnas.1010383107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou J, Sackton TB, Martinsen L, Lemos B, Eickbush TH, et al. (2012) Y chromosome mediates ribosomal DNA silencing and modulates the chromatin state in Drosophila. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. Available:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22665801. Accessed 15 June 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28. Paredes S, Branco AT, Hartl DL, Maggert KA, Lemos B (2011) Ribosomal DNA deletions modulate genome-wide gene expression: “rDNA-sensitive” genes and natural variation. PLoS Genet 7: e1001376 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Biessmann H, Prasad S, Semeshin VF, Andreyeva EN, Nguyen Q, et al. (2005) Two distinct domains in Drosophila melanogaster telomeres. Genetics 171: 1767–1777 10.1534/genetics.105.048827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Berloco M, Fanti L, Sheen F, Levis RW, Pimpinelli S (2005) Heterochromatic distribution of HeT-A- and TART-like sequences in several Drosophila species. Cytogenet Genome Res 110: 124–133 10.1159/000084944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. James TC, Elgin SC (1986) Identification of a nonhistone chromosomal protein associated with heterochromatin in Drosophila melanogaster and its gene. Mol Cell Biol 6: 3862–3872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. James TC, Eissenberg JC, Craig C, Dietrich V, Hobson A, et al. (1989) Distribution patterns of HP1, a heterochromatin-associated nonhistone chromosomal protein of Drosophila. Eur J Cell Biol 50: 170–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Eissenberg JC, James TC, Foster-Hartnett DM, Hartnett T, Ngan V, et al. (1990) Mutation in a heterochromatin-specific chromosomal protein is associated with suppression of position-effect variegation in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87: 9923–9927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cenci G, Siriaco G, Raffa GD, Kellum R, Gatti M (2003) The Drosophila HOAP protein is required for telomere capping. Nat Cell Biol 5: 82–84 10.1038/ncb902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Perrini B, Piacentini L, Fanti L, Altieri F, Chichiarelli S, et al. (2004) HP1 controls telomere capping, telomere elongation, and telomere silencing by two different mechanisms in Drosophila. Mol Cell 15: 467–476 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.06.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ebert A, Schotta G, Lein S, Kubicek S, Krauss V, et al. (2004) Su(var) genes regulate the balance between euchromatin and heterochromatin in Drosophila. Genes Dev 18: 2973–2983 10.1101/gad.323004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Stabell M, Bjørkmo M, Aalen RB, Lambertsson A (2006) The Drosophila SET domain encoding gene dEset is essential for proper development. Hereditas 143: 177–188 10.1111/j.2006.0018-0661.01970.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stabell M, Eskeland R, Bjørkmo M, Larsson J, Aalen RB, et al. (2006) The Drosophila G9a gene encodes a multi-catalytic histone methyltransferase required for normal development. Nucleic Acids Res 34: 4609–4621 10.1093/nar/gkl640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Seum C, Bontron S, Reo E, Delattre M, Spierer P (2007) Drosophila G9a is a nonessential gene. Genetics 177: 1955–1957 10.1534/genetics.107.078220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Clough E, Moon W, Wang S, Smith K, Hazelrigg T (2007) Histone Methylation Is Required for Oogenesis in Drosophila. Development 134: 157–165 10.1242/dev.02698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Volpe TA, Kidner C, Hall IM, Teng G, Grewal SIS, et al. (2002) Regulation of heterochromatic silencing and histone H3 lysine-9 methylation by RNAi. Science 297: 1833–1837 10.1126/science.1074973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pal-Bhadra M, Leibovitch BA, Gandhi SG, Rao M, Bhadra U, et al. (2004) Heterochromatic silencing and HP1 localization in Drosophila are dependent on the RNAi machinery. Science 303: 669–672 10.1126/science.1092653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Verdel A, Jia S, Gerber S, Sugiyama T, Gygi S, et al. (2004) RNAi-mediated targeting of heterochromatin by the RITS complex. Science 303: 672–676 10.1126/science.1093686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lee YS, Nakahara K, Pham JW, Kim K, He Z, et al. (2004) Distinct roles for Drosophila Dicer-1 and Dicer-2 in the siRNA/miRNA silencing pathways. Cell 117: 69–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Okamura K, Ishizuka A, Siomi H, Siomi MC (2004) Distinct roles for Argonaute proteins in small RNA-directed RNA cleavage pathways. Genes & Development 18: 1655–1666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sun F-L, Haynes K, Simpson CL, Lee SD, Collins L, et al. (2004) cis-Acting determinants of heterochromatin formation on Drosophila melanogaster chromosome four. Mol Cell Biol 24: 8210–8220 10.1128/MCB.24.18.8210-8220.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Haynes KA, Caudy AA, Collins L, Elgin SCR (2006) Element 1360 and RNAi components contribute to HP1-dependent silencing of a pericentric reporter. Current Biology 16: 2222–2227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sentmanat MF, Elgin SCR (2012) Ectopic assembly of heterochromatin in Drosophila melanogaster triggered by transposable elements. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 14104–14109 10.1073/pnas.1207036109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kharchenko PV, Alekseyenko AA, Schwartz YB, Minoda A, Riddle NC, et al. (2011) Comprehensive analysis of the chromatin landscape in Drosophila melanogaster. Nature 471: 480–485 10.1038/nature09725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Riddle NC, Leung W, Haynes KA, Granok H, Wuller J, et al. (2008) An investigation of heterochromatin domains on the fourth chromosome of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 178: 1177–1191 10.1534/genetics.107.081828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shaffer CD, Wuller JM, Elgin SC (1994) Raising large quantities of Drosophila for biochemical experiments. Methods Cell Biol 44: 99–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Dimitri P (2004) Fluorescent in situ hybridization with transposable element probes to mitotic chromosomal heterochromatin of Drosophila. Methods Mol Biol 260: 29–39 10.1385/1-59259-755-6:029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.(2012) R Core Team (n.d.) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. p. Available:http://www.R-project.org/.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The genotypes of all fly lines used in this study are shown (middle column), with the source (lab and pertinent reference) given (right-hand column). If the stock is available from the Bloomington Stock Center, the stock number is provided (left-hand column).

(DOCX)