Abstract

Unfavourable outcomes are part and parcel of performing surgeries of any kind. Unfavourable outcomes are results of such work, which the patient and or the clinician does not like. This is an attempt to review various causes for unfavorable outcomes in orthognathic surgery and discuss them in detail. All causes for unfavorable outcomes may be classified as belonging to one of the following periods A) Pre- Treatment B) During treatment Pre-Treatment: In orthognathic surgery- as in any other discipline of surgery- which involves changes in both aesthetics and function, the patient motivation for seeking treatment is a very important input which may decide, whether the outcome is going to be favorable or not. Also, inputs in diagnosis and plan for treatment and its sequencing, involving the team of the surgeon and the orthodontist, will play a very important role in determining whether the outcome will be favorable. In other words, an unfavorable outcome may be predetermined even before the actual treatment process starts. During Treatment: Good treatment planning itself does not guarantee favorable results. The execution of the correct plan could go wrong at various stages which include, Pre-Surgical orthodontics, Intra and Post-Operative periods. A large number of these unfavorable outcomes are preventable, if attention is paid to detail while carrying out the treatment plan itself. Unfavorable outcomes in orthognathic surgery may be minimized If pitfalls are avoided both, at the time of treatment planning and execution.

KEY WORDS: Orthognathic surgery, outcome, unfavourable

INTRODUCTION

“Unfavourable” according to the oxford dictionaries means undesirable outcome. Understanding unfavourable outcomes and managing them are an important part of any surgical exercise. However, a subtle distinction between complications and unfavourable outcomes will have to be made at the outset. Complications are unintended and undesirable consequences of a pre-existing disorder or its treatment, which may or may not have a lasting impact on the outcome, for e.g., excessive bleeding at the time of surgery. Unfavourable outcomes on the other hand may or may not be a result of complications, but which leads to results, which are unsatisfactory to the patient, the clinician or both.

For ease of discussion, the causes for unfavourable outcomes in orthognathic surgery may be classified as:

Pre-treatment

During treatment.

Let us first list out the causes under each group and then discuss them in a little greater detail.

PRE-TREATMENT

Lack of internal motivation

Unrealistic expectations, (both of which are patient dependent factors)

Lack of understanding of treatment objectives

Lack of adequate/proper clinical evaluation

Lack of team work

Wrong treatment plan (while the last four are clinician dependent).

This set of causes though, a little ambiguous at times, are the most important reasons for unfavourable outcomes.

Lack of internal motivation

This is a problem particularly relevant in the Indian cultural scenario. Often times, it is the parents that bring the daughter, to improve her looks so that she could be married off and things such as these.[1] It may be difficult to ascertain whether the patient herself thinks she needs the surgery, is keen to get it performed i.e., internal motivation. It may be that she is not concerned with it. In this situation, it may be easy to state that these cases should not be performed, as literature might suggest. However, we believe that this is a difficult question to answer and one answer may not fit all situations. In other words, you may decide to go ahead with the surgery being well aware of the drawbacks of doing so.

Unrealistic expectations

Expectations of patients from the surgery may be generally two-fold:

Physical changes, which are directly responsible for them to look good or attractive

The non-physical attributes, which may be indirectly responsible for their well-being such as self-esteem, body image and social image[2]

The physical problems can be addressed as they generally are quantifiable and can be predicted to a great degree with expectations being satisfied while the indirect components, which are psychosocial, may not fall within the predictable outcome bracket.[3] Expectations to improvement with relation to the indirect attributes generally show a greater degree of unfavourable outcome.[2] And these need to be evaluated and discussed in detail during the patients counselling for surgery. Patients exhibiting ‘dysmorphophobic’ tendencies should be referred for psychiatric evaluation and counselling before surgery is planned.[4] Expectations also vary with factors such as the individual's personality, upbringing and social relationship.[5]

Unrealistic expectations could be a continuation of the previous problem where the parents etc., desire dramatic results, which may be unattainable. More often we are exposed to patients and their parents who assume that surgery is a comprehensive solution to every problem in making things “picture perfect”. Furthermore, there may be clinical situations where the patient themselves have an intrinsic desire to look such as a particular person or celebrity post-surgically. These patients may have a tendency to ‘shop’ for the right surgeon who can promise them results in accordance with the images/pictures they may carry. This may reflect an extremely obsessive attitude with a degree of narcissism and may not be suitable candidates for surgery. The outcome rating of laypersons after an orthognathic procedure is always less than that of a professional. This also goes to show that generally, a patient has a higher degree of expectation from a surgery than the clinician.[6] A thorough evaluation of the patient's expectations and a realistic discussion of the surgical outcomes have to be carried out during the patients counselling. If the patients accept your limitations in achieving the desired outcome one can proceed, else it may be advisable to refuse them treatment.[3,5] (There have been instances where patients have been driven to attempt suicide because they did not like what they saw after the surgery).

Lack of understanding of treatment objectives

Orthognathic surgery and its outcomes are a result of a complex planning and treatment process, which involves inputs from a team, which includes the patient. If any member of the team including the patient has not understood the objectives of the proposed treatment we could end up having unfavourable outcomes. This can be divided into two main categories: (1) Conflict between achieving better aesthetics versus better function and (2) the perception of aesthetics between the clinician and the patient involved (generalised vs. individualistic).[6–8] While, it is easy to understand the need for aesthetic improvement, it is not very clear when it comes to understanding functional improvement, particularly by the patient. The surgeon and or the orthodontist involved may be interested in producing a result, which improves the function of the jaws, the patients concern to begin with is only aesthetics and hence she may not understand the need for improved function.[9–11] More importantly this contradiction of priorities might produce a clash between the surgeon and the orthodontist and if it is not resolved before the treatment is started, might end up in results that somebody is not happy with. A survey of patients also reveal that there is poor communication between the patient and the clinician in terms of treatment needs and the patient also exhibits poor decision making in assessing the needs himself.[12]

Lack of adequate/proper clinical evaluation

This is very obvious. However, this needs to be emphasised because the end result can be disastrous if proper evaluation of the deformity is not carried out (It is beyond the scope of this discussion as to what is proper/adequate clinical evaluation). All the surgical procedures of the face can be basically divided into five groups.[10]

Single jaw-upper

Single jaw-lower

Bimaxillary-upper and lower

Bimaxillary with rotation of the maxilla-mandibular complex and

Chin procedures.

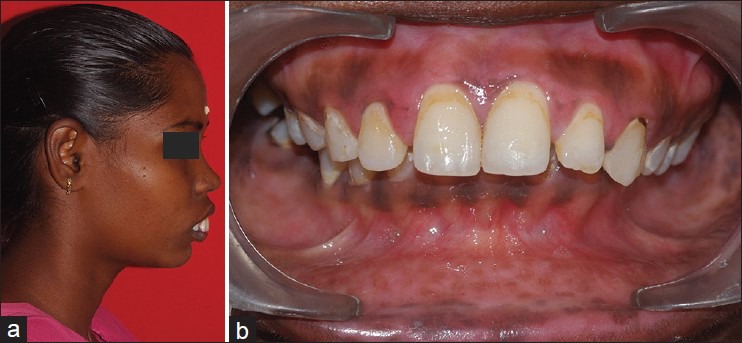

The patient needs to be assessed for functional, structural and aesthetic concerns and planned for the indicated procedure after a thorough evaluation has been completed. A change of procedure from the indicated one may lead to an unfavourable result. A few examples to clarify this point are explained. For e.g., let us consider a skeletal class 3 situation with a concave profile. The problem can be due to a retrognathic maxilla or a prognathic mandible or even a combination of both. The surgical plan for this may be either a mandibular setback or a maxillary advancement or a combination bimaxillary procedure. If the diagnosis of the deformity is not correct from the evaluation, a wrong procedure may result in an unfavourable or a suboptimal outcome [Figure 1]. Similarly, a clear distinction needs to be made in the favour of a single or a bimaxillary surgery based on the evaluation and investigations. This will play a major role in the immediate outcome, as well as long-term stability reducing relapse. Similarly, deformities may occur in more than one planes i.e., vertical, transverse and sagittal anterior-posterior (AP). If all dimensions of the deformity is not understood the problem in one plane, for e.g., AP dimension may be addressed leaving the others uncorrected, once again leading to unfavourable results [Figure 2].

Figure 1.

(a) Different skeletal pattern for the same profile problem. Class 3 patient with isolated maxillary retrognathism. (b) Class 3 patient with isolated mandibular prognathism. (c) Class 3 patient with bimaxillary problem

Figure 2.

(a) Photographs demonstrating anterio-posterior and transverse skeletal disturbances in the same patient. Patient demonstrating skeletal class 2 relationship with anterio-posterior discrepancy. (b) Same patient demonstrating severe discrepancy in the transverse plane

Lack of team work

Team work is the essence of a good outcome. This involves joint clinic discussions, which are essentially led by the surgeon and the orthodontist but also involve the skill of periodontists, prosthodontists, clinical psychologist, anesthetist and a nutritionist.[9,13,14] The treatment of a patient does not end with the surgery, but also involves his comprehensive rehabilitation from the surgery, which includes his dental and general health status. The importance of this has already being alluded to, in the discussion of treatment objectives. It is extremely important that the surgeon and the orthodontist understand each other well and concur on the plans, which enables them to prioritise the treatment sequence. Orthognathic surgery is inseparable with orthodontics, which may be pre-surgical or post-surgical depending upon the indications.[9–11] The indications and necessity for a surgical procedure should be clearly understood by both the surgeon and the orthodontist and a favourable decision made to facilitate treatment, which may take the form of a surgery or only camouflage orthodontics.[11] The classical example of a so called camouflage orthodontics could be cited here. A person with a skeletal deformity may undergo isolated orthodontic correction to mask the skeletal deformity instead of correcting the basal bone problem, for e.g., by compensating the dental inclinations. This makes a subsequent surgical procedure difficult as the orthodontics needed for surgery takes the opposing course of camouflage orthodontics. Hence once the plan is charted in conjunction with the patient, a definitive sequence for treatment is followed, which may prevent chances for an undesirable post-treatment outcome.[11] The need for other specialists to be involved depends upon the dental treatment needs of the patient and the necessity for him to undergo post-surgical counselling.

Wrong treatment plan

This once again is a very obvious problem and stems from mistakes made in all the previous issues discussed earlier. It is therefore important to revisit a treatment plan formulated by the team before starting the treatment, explain to the patient the process involved (which may be long drawn out) and proceed when everybody concerned is on board.

DURING TREATMENT

The causes for unfavourable results in orthognathic surgery, which occur during the treatment can be divided into various categories viz.,

Inadequate/improper pre-surgical orthodontics

Lab errors during pre-surgical preparation including model surgery

Intra-operative errors

Post-operative sequelae.

Inadequate or improper orthodontics

The orthodontist and the surgeon have equal responsibility in achieving a good outcome for a patient requiring ortognathic surgery. The orthodontist has the role of setting the dental framework into the relationship that will be stable and functional once the surgery has been completed. In contrast to the conventional sequence of orthodontics preceding surgery and then following up for minor occlusal settling, recently there have been surgical indications where surgery can be performed first and later followed by orthodontics. The surgeon and the orthodontist should have a good understanding of their roles and should communicate efficiently to determine a comprehensive treatment plan, which will provide the best outcome for the patient[15–17] in all planes - coronal, sagittal and transverse. Problems occurring due to improper orthodontics can be classified as:

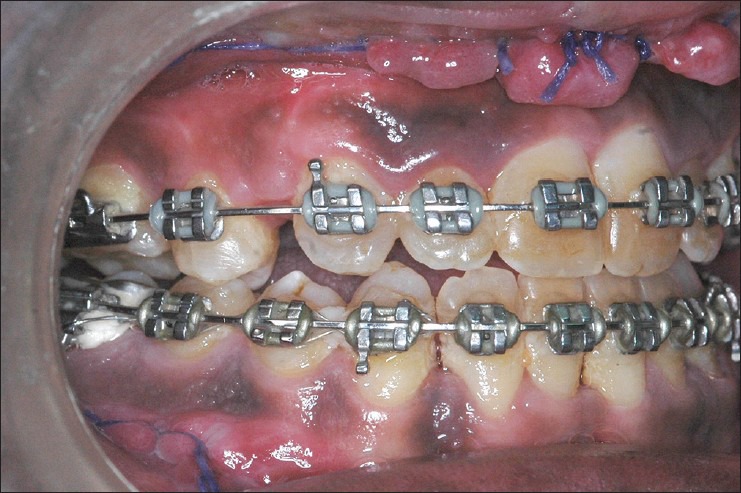

Insufficient decompensation

It is very important that the inclinations of the teeth in both the upper and lower arches are brought to their normal position before doing the surgery. This process will reflect the actual gravity of the skeletal deformity. The process of decompensation will obviously aggravate the abnormality clinically for e.g., in a class 3 skeletal deformity the dental overjet will become worse or more reverse i.e., the upper incisors may be pushed further behind the lower incisors than what was when the patient reported. If this has not been done adequately then the outcome will not be good [Figures 3–5]. This step also involves levelling the occlusal arches.

Figure 3.

Dental relationship before orthodontic treatment

Figure 5.

Dental relationship after surgery

Figure 4.

Dental relationship after orthodontic decompensation. (Exaggerated reverse overjet visible)

Inadequate transverse co-ordination

At times, the upper and or lower arches may be collapsed at the start of pre-surgical orthodontics. The arches need to be expanded to extent, that, when the surgery is performed the upper and lower arches are in a good position. Over or under expansion will lead to poor transverse relationship between the upper and lower arches post-operatively.

Not only is a proper inter arch relationship useful for good function, but it also ensures a stable, result post-operatively. Poor inter digitation between the upper and lower teeth is often responsible for relapse after surgery and hence an unfavourable outcome. Improper transverse dental relationships both unilateral and bilateral (cross-bites) also need to be addressed adequately [Figures 6 and 7].

Figure 6.

Unilateral cross-bite

Figure 7.

Unilateral cross-bite corrected post-orthodontics and surgery

Inadequate root divergence in segmental surgery

When segmental surgery is carried out i.e., interdental osteotomies are carried out breaking the maxilla or mandible into segments, It is important that there is adequate space between the roots of the teeth to carry out these osteotomies failing, which sectioning of roots and subsequent problems with those teeth and roots compromises outcome.[18]

Planning for extractions to facilitate adequate movement and accommodate bimaxillary procedures

Once the basic treatment plan has been decided if the patient will need a single jaw or a bimaxillary procedure the extraction of teeth to create an optimal dental overjet (positive in a class 2 skeletal base and negative in a class 3 base) to accommodate the necessary skeletal movement may have to be planned meticulously to facilitate proper surgical outcome. For example in a class 3 problem where only a mandibular setback is needed, it can be achieved with a non-extraction treatment plan, whereas the same patient if he needs a bimaxillary procedure (maxillary advancement and a mandibular setback) he may need extraction of the upper premolars to create an increased negative overjet to facilitate a bimaxillary procedure, failing, which a pleasing profile may not be achievable.

Lab errors during pre-surgical preparation including model surgery

Orthognathic surgery involves a fair share of laboratory work as it requires a lot of planning and simulated surgery, which have to be carried out on dental models in-vitro to create an occusal wafer, which is used as a template to duplicate the desired skeletal positioning on the patient in a precise manner.[19,20] It is paramount that all the laboratory work in preparation for the surgery be done precisely and in accordance to the predetermined treatment plan as any deviation or errors in the lab will reflect on a compromised final surgical outcome.

Unsatisfactory bite registration

Registration of the patient's occlusal (inter-arch) relationship is called bite registration and it reflects the position of the jaws in relation to the teeth. This is performed with either wax or bites registration polymers in the patients-centric relationship and has to be transferred to the articulator, which will mimic the position of the jaws with the movement of the temporomandibular Joint. Any discrepancy in this will totally alter the surgical simulation and the surgical wafer fabrication.

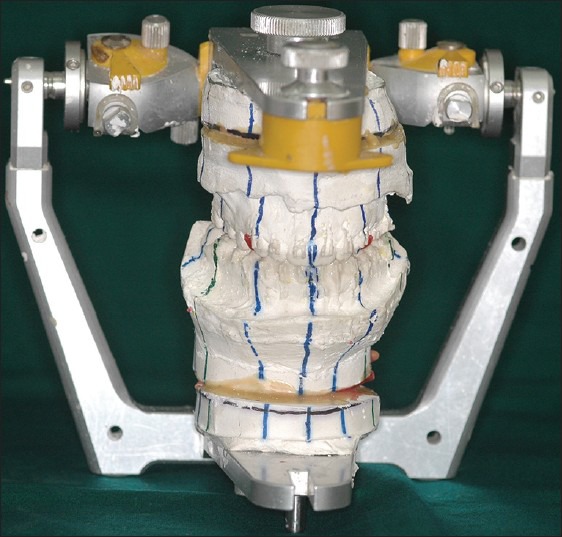

Transfer of the dental casts to the articulator

This involves the transfer of the in-vivo relationship of the maxilla and the mandible to a semi or a fully adjustable articulator by use of a face-bow. Discrepancies in the transfer of the dental models to the articulator can create a change in the three dimensional spatial relationship of the maxilla and the mandible.[21–23] This may include shift of dental midlines, creation of occlusal canting where non-existent and incorporation of rotational movements in the treatment plan. This can be minimised by proper techniques of marking orientation lines for the teeth and marking the heel of the maxilla and the mandible, which preserve the in-vivo relationship on the dental models [Figure 8].

Figure 8.

Models mounted in a SAM 3 articulator with the orientation lines marked

Improper model surgery (simulation)

A good treatment plan will not necessarily translate into a good outcome if the model surgeries are not performed properly. The model surgery should accurately reflect the treatment plan for e.g., 3 mm superior repositioning with 5 mm advancement of the maxilla and 6 mm mandibular setback [Figure 9]. More complex the movements i.e., in more than 1 direction or multi-segment surgery greater are the need for accuracy in model surgery. The intraoperative wafers that are used as surgical templates are fabricated on the models after model surgery is performed. Lack of accuracy with this leads to many problems post-operatively.

Figure 9.

Use of Ericsson platform for measuring movements during the surgical simulation (Courtesy: Dr. Pramod Subash, Cochin)

Warpage/physical deformation of the occlusal wafer

It is a very common reason for failure of the simulation phase when all the preceding issues have been sorted out properly. They can deform due to exposure to atmospheric air and temperature easily and may not fit on the patient's dentition intraoperatively. This will then lead to positioning of the jaws arbitrarily and can give rise to poor aesthetic and functional results. The common reasons for deformation of the wafer are that it is either prepared too early or is stored improperly. The best way to preserve the wafer is to place it in position on the dental models and retain it with the articulator [Figure 10].

Figure 10.

Occlusal wafers on the model (Courtesy: Dr. Pramod Subash, Cochin)

Intraoperative errors

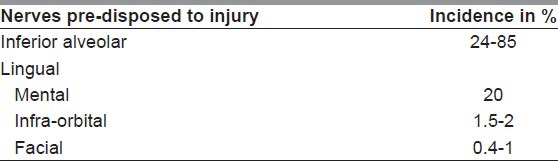

Neurological deficit

Sensory nerve deficit, which is now termed ‘altered sensation’ following orthognathic surgery may be transient or permanent.[24] Permanent sensory deficit is certainly an undesirable outcome, which has to be discussed with the patient and explained in detail. An informed consent explaining the expected complications and their sequel would facilitate a better understanding of the issues by the patient and save post-surgical embarrassment or litigation for the clinician.

The nerves that may be injured and the relative occurrence values have been enumerated in Table 1. The inferior alveolar and mental nerves are the most commonly involved in terms of sensory deficit and mandates a more detailed discussion. The chances of inferior alveolar nerve transection may range between 1.3% and 18%, whereas long-term sensory loss without any transection of the nerve still ranges between 24% and 85%. The incidence of mental nerve deficit during genioplasty is 20% while a combined procedure of genioplasty and sagittal split osteotomy (SSO) increases the chances of sensory deficit to almost 70%.[25]

Table 1.

Nerves predisposed to injury

Unfavourable fractures/bad splits

Unfavourable fractures or splits can occur due to incomplete osteotomy or improper techniques. It is mandatory to revisit all the osteotomy sites when there is any form of resistance during the down-fracture of the maxilla or splitting of the mandible.

Maxilla

Unfavourable fracture lines can cause fragmentation of the bones in the maxilla and may produce difficulty in fixation and may also permeate through to the skull base producing deleterious effects like blindness. The chances for a bad fracture is more common in a lefort 1 osteotomy when the conventional lines are modified to include the infra-orbital rim or zygoma where the osteotomy may have to be blind behind the zygoma.[25]

Mandible

The incidence of unfavourable splits occurring in the mandible has been reported to be around 0.5-5%.[25] However, a recent large series of SSOs indicates a much lower incidence of 0.7% in 2005 surgical sites.[26] The most common bad splits reported are fracture of the ramus, fracture of the buccal plate or the lingual plate. Fragmentation of the buccal plate is rare. Most often these are comfortably managed intraoperatively by modifying the fixation methods. The presence of an unerupted third molar in the mandible increases the chances for a bad split.[27]

Ophthalmic causes for unfavourable outcome

Nine cases of blindness have been reported following orthognathic surgery.[27,28] Essentially, lefort 1 osteotomy and one due to bilateral maxillary posterior segmental osteotomy.[29] One case of transient abducens nerve palsy has also been reported.[30] Injuries to the distal orifice of the nasolacrimal duct and the anterior wall of the lacrimal sac have also been reported. The causes for blindness following a lefort 1 osteotomy have been postulated as unknown in five cases, arterial aneurysm in one case, hypoperfusion of the optic nerve[28] in one case and two cases where investigations showed propagation of fractures lines to the skull base during pterygomaxillary disjunction.[31]

Vascular compromise

Complete or partial necrosis of the osteotomized segment due to vascular compromise has been reported more in the maxilla and has been attributed more predominantly to cases requiring multi-segment osteotomies in conjunction with superior repositioning and or transverse discrepancy corrections.[32] Partial necrosis of the anterior maxilla after an anterior maxillary osteotomy has also been reported.[33] The occurrence of palatal perforations also compromise the vascularity of the anterior maxilla.[34]

Excessive stripping of the lateral ramus also is not advocated to prevent ischemia to the proximal segment of the ramus. Maintenance of a good muscle pedicle enhances supply to this segment. However, two cases of aseptic necrosis of the mandible following osteotomies have been reported.[35]

Nasal changes

Intra nasal problems such as deviation of the nasal septum, fracture of the anterior nasal spine, synechiae, septal perforations and hypertrophy of the inferior turbinates have been reported.[36] Septal deviations are the most frequently noted undesirable change after a lefort 1 osteotomy. This happens due to the repositioning of the cartilaginous septum, vomer and the anterior nasal spine especially during a lefort 1 impaction. Once this has been identified, trimming of the septal cartilage and the vomer may be advocated to correct the deformity.[36] An 8% incidence of snoring post-surgically has also been documented.[36] Changes of the inferior turbinate following surgery also needs to be noted and addressed as it is a significant cause of post-surgical nasal obstruction.[36]

Morphological changes of the nasal base, position and rotation of the nasal tip are also significant changes that need to be expected with maxillary surgeries. Widening of the alar base is a universal phenomenon with almost any maxillary osteotomy and is more prominent in superior repositioning and advancement procedures. This is due to the stripping of the muscles of the nasolabial region due to the sub-periosteal dissection for bony exposure. These can be managed adequately by the judicious use of V-Y closures and the alar cinch stitch.[37,38]

Soft-tissue injuries

Around 2% incidence of soft-tissue injuries has been documented,[39] which may produce a bad result in the immediate post-surgical phase with significant patient dissatisfaction and discomfort. This may be due traction injuries, thermal burns or injuries due to injudicious use of cutting instruments without adequate protection.

Unfavourable outcome in the post-operative phase

Velopharyngeal incompetence

Studies have indicated that there is an alteration in the anatomy and functioning of the velopharyngeal apparatus after a total maxillary osteotomy and this may not be very different between cleft and non-cleft patients. However, the magnitude of the change may be different in the two groups, which may need consideration during advancements of the maxilla in cleft patients. The presence of a short soft palate and a deep pharynx contribute to the development of a velopharyngeal insufficiency following lefort 1 osteotomy.[40–42] In general, advancement of less than 10 mm may be unlikely to produce any significant undesirable changes in the speech of the subject even in cleft patients.[41,42]

Condylar resorption

Condylar resorption is a progressive change in the shape of the condyle with a decrease in its mass. This may lead to decreased posterior facial height, retrognathia, worsening anterior open bite with downwards rotation of the mandible. A systematic review of a sample size of 2567 patients yielded very poor evidence, but stated that the incidence is about 5.3% and was predominant in females with mandibular retrognathism and high mandibular plane angle who underwent bimaxillary surgery.[43]

Hardware problems

Undesirable results due to hardware issues may be exhibited in two forms. Problems associated with the implants used for fixation and problems arising due to the instrument or bur breakage intraoperatively. Instrument or bur breakage in orthognathic surgery may be a relatively common occurrence, but seldom causes any deleterious effects. However, exaggerated tissue response due to an unrecovered bur in a patient has been documented to produce an osteolytic foreign body reaction.[44]

A study of 570 orthognathic procedures revealed that 27.5% of patients needed removal of the plates used for fixation, where 13.7% were due to post-operative plate-related infections and 11.6% were due to clinical irritations due to the plates.[45]

Dental pulpal vitality

Transient or persistent dental hypersensitivity may be a common problem associated with post-osteotomy discomfort. Patients may also exhibit obliteration of the pulp canal, which is more prevalent in the maxilla. Spontaneous pulpal necrosis or internal resorption of the tooth are not common.[46] The transient ischaemia following an osteotomy for the first 2 days followed by increased pulpal blood flow may be the cause of the hyperaemia and sensitivity.[47]

Condylar sag and condylar torque

Condylar sag is an immediate or late alteration in the position of the condylar process in the glenoid fossa after the fixation of the osteotomy, which leads to a change in the dental occlusion from the predetermined plan. Sag may manifest as a central sag where the condyle is at a lower position than normal and peripheral sag is when the condyle is forced more medial and anterior against the walls of the fossa after fixation.[48] These changes may manifest as open-bites, unilateral or bilateral cross-bites or anteropositioning of the mandible post-surgically. Condylar torque also causes shifting of the dental midline post-surgically and may also lead to temporomandibular joint dysfunctions.[49] Condylar sag and torque may be prevented by careful repositioning of the condyle manually within the fossa before rigid fixation of the bony fragments.[48]

Dental occlusion disturbances

Dental occlusal disturbances may occur in the form of anterior-open bites, cross-bites, change in the dental midlines and altered inter-digitation of the teeth. The most common causes for altered occlusion in the immediate post-operative phase are due to improper condylar positioning intraoperatively. This produces condylar sag or torque, which produces unfavourable occlusion, which hinders function and decreases post-surgical stability.

Anterior open-bite is the most common undesirable dental outcome post-operatively and may be due to (1) Central condylar sag, (2) Improper positioning of the maxilla intraoperatively or (3) Excessive muscular forces.[48]

Non-union

Non-union or delayed union is seen predominantly in the maxilla following orthognathic surgery and has been documented with incidence of 2.6%.[50] the main causes of non or delayed union are instability in dental occlusion, post-surgical infections or osteosynthesis failures.[34] Investigations with a 3D computed tomography reconstruction may be superior than conventional radiography in making a diagnosis of non-union. Secondary surgery with curettage, bone grafting and adequate rigid fixation need to be performed as a corrective measure.[50]

Persistent growth after orthognathic surgery

Surgery during the growing phase also has two significant ill-effects: (1) The remaining growth potential in the patient may be hampered and (2) the growth may continue after surgery and negate the benefits of surgical correction. However, a thorough understanding of the indications for surgery and growth implications will enable us to make a decision of the need to operate during the growth phase.[51,52] Nearly, 98% of the growth potential may be exhausted in females by the age of 15 and in males by 18.[53,54] The need for surgery in the growing phase may be many including exacerbation of the existing problem, psychosocial considerations, airway problems, aesthetics and temporomandibular joint dysfunction etc.

Stability and relapse

No orthognathic procedure is relapse proof and when the surgical procedure is not planned, modified or over-corrected with this in mind, may lead to an undesirable result in due course. The concept of stability can be understood better in terms of percentage changes anticipated, which will enable us to plan in countering relapse.

Highly stable: Lesser than 10% chance of significant post-operative change

Stable: Less than 20% chance of significant change and almost no chance of major change post-operatively.

Stable with modification: E.g., rigid fixation after osteotomy

Problematic: Considerable chances for major post-operative changes.

A clear understanding of the ‘hierarchy of stability’ and planning accordingly will reduce the incidence of post-surgical problems. For example, three movements fall in the problematic category-mandibular setback, maxillary down-graft and maxillary expansion.[55] Knowledge and awareness of these help us to achieve better results and counsel the patients on what to anticipate.

Unusual situations of unfavourable outcome

Avulsion of Maxilla: One instance of avulsion of a left maxilla and palate has been reported in a 20 year old patient with a corrected bilateral cleft lip and palate deformity. Overzealous dissection and mobilisation has been reported as the cause.[56] These can be prevented by judicious handling of the tissues during surgery and use of intraoperative splints to consolidate a cleft maxilla into a single unit

Death: One instance of post-operative death has been reported following orthognathic surgery. A pre-existing condition of cardio-myopathy has been indicated as the cause for the mortality.[57]

CONCLUSION

Complications and unfavourable outcomes are part and parcel of any surgical practice and orthognathic surgery is no exception. However, a majority of these instances may be avoided if a systematic approach to planning and execution is adopted.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Garvill J, Garvill H, Kahnberg KE, Lundgren S. Psychological factors in orthognathic surgery. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1992;20:28–33. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(05)80193-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ryan FS, Barnard M, Cunningham SJ. What are orthognathic patients’ expectations of treatment outcome: A qualitative study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;70:2648–55. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pabari S, Moles DR, Cunningham SJ. Assessment of motivation and psychological characteristics of adult orthodontic patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011;140:e263–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2011.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cunningham SJ, Hunt NP, Feinmann C. Psychological aspects of orthognathic surgery: A review of the literature. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1995;10:159–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ryan FS, Barnard M, Cunningham SJ. Impact of dentofacial deformity and motivation for treatment: A qualitative study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2012;141:734–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2011.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fabré M, Mossaz C, Christou P, Kiliaridis S. Professionals’ and laypersons’ appreciation of various options for Class III surgical correction. Eur J Orthod. 2010;32:395–402. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjp104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vargo JK, Gladwin M, Ngan P. Association between ratings of facial attractivess and patients’ motivation for orthognathic surgery. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2003;6:63–71. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0280.2003.2c097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reyneke J. Essentials of Orthognathic Surgery. Ilinois: Quintessence Books; 2003. Diagnosis and treatment planning. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson L, Kahnberg K, Pogrel M. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. United Kingdom: Willey Blackwell, Sussex; 2010. Diagnosis and treatment planning, dentofacial deformities. Esthetic objectives and surgical solutions; p. 993. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Proffit W, White R, Sarver D. St Louis: Mosby; 2003. Contemporary management of dentofacial deformities: Treatment planning: Optimizing benefit to the patient; p. 203. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stirling J, Latchford G, Morris DO, Kindelan J, Spencer RJ, Bekker HL. Elective orthognathic treatment decision making: A survey of patient reasons and experiences. J Orthod. 2007;34:113–27. doi: 10.1179/146531207225022023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khattak ZG, Benington PC, Khambay BS, Green L, Walker F, Ayoub AF. An assessment of the quality of care provided to orthognathic surgery patients through a multidisciplinary clinic. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2012;40:243–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ryan F, Shute J, Cedro M, Singh J, Lee E, Lee S, et al. A new style of orthognathic clinic. J Orthod. 2011;38:124–33. doi: 10.1179/14653121141353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grubb J, Evans C. Orthodontic management of dentofacial skeletal deformities. Clin Plast Surg. 2007;34:403–15. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaban L, Pogrel M. Orthognathic Surgery. Pennsylvania: W B Saunders; 1997. Complications in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lo FM, Shapiro PA. Effect of presurgical incisor extrusion on stability of anterior open bite malocclusion treated with orthognathic surgery. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1998;13:23–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Proffit W, White R, Sarver D. Contemporary Management of Dentofacial Deformities. St. Louis: Mosby; 2003. Combining orthodontics and surgery: Who does what and when; p. 251. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reyneke J. Diagnosis and Treatment Planning, Essentials of Orthognathic Surgery. Illinois: Quintessence Books; 2003. Development of visual treatment objectives; p. 139. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruiz RL, Blakey GH, Erickson KL, Bell WH, Goldsmith DH. Model surgery. In: Fonseca RJ, editor. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. Vol. 2. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2000. pp. 98–148. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paul PE, Barbenel JC, Walker FS, Khambay BS, Moos KF, Ayoub AF. Evaluation of an improved orthognathic articulator system: 1. Accuracy of cast orientation. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;41:150–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2011.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolford LM, Galiano A. A simple and accurate method for mounting models in orthognathic surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:1406–9. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olszewski R. Sharifi A, Jones R, Ayoub A, Moos K, Walker F, Khambay B, McHugh S, editors. Re: How accurate is model planning for orthognathic surgery? Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;37:1089–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2008.06.011. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2009;38:1009-10; author reply 1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Essick GK, Phillips C, Turvey TA, Tucker M. Facial altered sensation and sensory impairment after orthognathic surgery. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;36:577–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morris DE, Lo LJ, Margulis A. Pitfalls in orthognathic surgery: Avoidance and management of complications. Clin Plast Surg. 2007;34:e17–29. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Falter B, Schepers S, Vrielinck L, Lambrichts I, Thijs H, Politis C. Occurrence of bad splits during sagittal split osteotomy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;110:430–5. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mehra P, Castro V, Freitas RZ, Wolford LM. Complications of the mandibular sagittal split ramus osteotomy associated with the presence or absence of third molars. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59:854–8. doi: 10.1053/joms.2001.25013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lanigan DT, Romanchuk K, Olson CK. Ophthalmic complications associated with orthognathic surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993;51:480–94. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(10)80502-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Girotto JA, Davidson J, Wheatly M, Redett R, Muehlberger T, Robertson B, et al. Blindness as a complication of Le Fort osteotomies: Role of atypical fracture patterns and distortion of the optic canal. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102:1409–21. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199810000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li KK, Meara JG, Rubin PA. Orbital compartment syndrome following orthognathic surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995;53:964–8. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(95)90294-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanu-Cernat LM, Hall T. Late onset of abducens palsy after Le Fort I maxillary osteotomy. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;47:414–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tomasetti BJ, Broutsas M, Gormley M, Jarrett W. Lack of tearing after Le Fort I osteotomy. J Oral Surg. 1976;34:1095–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lanigan DT, Hey JH, West RA. Aseptic necrosis following maxillary osteotomies: Report of 36 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;48:142–56. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(10)80202-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gunaseelan R, Anantanarayanan P, Veerabahu M, Vikraman B, Sripal R. Intraoperative and perioperative complications in anterior maxillary osteotomy: A retrospective evaluation of 103 patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:1269–73. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kramer FJ, Baethge C, Swennen G, Teltzrow T, Schulze A, Berten J, et al. Intra-and perioperative complications of the LeFort I osteotomy: A prospective evaluation of 1000 patients. J Craniofac Surg. 2004;15:971–7. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200411000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lanigan DT, West RA. Aseptic necrosis of the mandible: Report of two cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;48:296–300. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(90)90397-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pingarrón Martín L, Arias Gallo LJ, López-Arcas JM, Chamorro Pons M, Cebrián Carretero JL, Burgueño García M. Fibroscopic findings in patients following maxillary osteotomies in orthognathic surgery. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2011;39:588–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2010.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schendel SA, Carlotti AE., Jr Nasal considerations in orthognathic surgery. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1991;100:197–208. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(91)70056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schendel SA, DeLaire I. Facial muscles: form, function and reconstruction in dentofacial deformities. In: Bell WH, editor. Surgical Correction of Dentofacial Deformities: New Concepts. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1985. pp. 259–315. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim SG, Park SS. Incidence of complications and problems related to orthognathic surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:2438–44. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2007.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schendel SA, Oeschlaeger M, Wolford LM, Epker BN. Velopharyngeal anatomy and maxillary advancement. J Maxillofac Surg. 1979;7:116–24. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0503(79)80023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Padwa BL. Predictors of velopharyngeal incompetence in cleft patients following le fort I maxillary advancement. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67(Suppl):45–6. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Phillips JH, Klaiman P, Delorey R, MacDonald DB. Predictors of velopharyngeal insufficiency in cleft palate orthognathic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115:681–6. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000152433.29134.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Moraes PH, Rizzati-Barbosa CM, Oíate S, Moreira RW, de Moraes M. Condylar resorption after orthognathic surgery: A systematic review. Int J Morphol. 2012;30:1023–8. doi: 10.4067/S0717-95022012000300042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manikandhan R, Anantanarayanan P, Mathew PC, Kumar JN, Narayanan V. Incidence and consequences of bur breakage in orthognathic surgery: A retrospective study with discussion of 2 interesting clinical situations. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69:2442–7. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Falter B, Schepers S, Vrielinck L, Lambrichts I, Politis C. Plate removal following orthognathic surgery. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;112:737–43. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ellingsen RH, Artun J. Pulpal response to orthognathic surgery: A long-term radiographic study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1993;103:338–43. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(93)70014-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Justus T, Chang BL, Bloomquist D, Ramsay DS. Human gingival and pulpal blood flow during healing after Le Fort I osteotomy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59:2–7. doi: 10.1053/joms.2001.19251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reyneke JP, Ferretti C. Intraoperative diagnosis of condylar sag after bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomy. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;40:285–92. doi: 10.1016/s0266-4356(02)00147-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hackney FL, Van Sickels JE, Nummikoski PV. Condylar displacement and temporomandibular joint dysfunction following bilateral sagittal split osteotomy and rigid fixation. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;47:223–7. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(89)90221-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Imholz B, Richter M, Dojcinovic I, Hugentobler M. Non-union of the maxilla: A rare complication after Le Fort I osteotomy. Rev Stomatol Chir Maxillofac. 2010;111:270–5. doi: 10.1016/j.stomax.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wolford LM, Karras SC, Mehra P. Considerations for orthognathic surgery during growth, part 1: Mandibular deformities. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2001;119:95–101. doi: 10.1067/mod.2001.111401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wolford LM, Karras SC, Mehra P. Considerations for orthognathic surgery during growth, part 2: Maxillary deformities. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2001;119:102–5. doi: 10.1067/mod.2001.111400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Broadbent BH, Sr, Broadbent BH, Jr, Golden WH. St Louis: CV Mosby; 1975. Bolton. Standards of dentofacial developmental growth. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Van der Linden F. Surrey, UK: Quintessence; 1986. Facial growth and facial orthopaedics. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bailey L’, Cevidanes LH, Proffit WR. Stability and predictability of orthognathic surgery. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2004;126:273–7. doi: 10.1016/S0889540604005207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bendor-Samuel R, Chen YR, Chen PK. Unusual complications of Le Fort I osteotomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96:1289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Van de Perre JP, Stoelinga PJ, Blijdorp PA, Brouns JJ, Hoppenreijs TJ. Perioperative morbidity in maxillofacial orthopaedic surgery: A retrospective study. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1996;24:263–70. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(96)80056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]