Abstract

Substantial improvements have occurred in the longevity of several groups of individuals with early-onset disabilities, with many now surviving to advanced ages. This paper estimates the population of adults aging with early-onset disabilities at 12-15 million persons. Key goals for the successful aging of adults with early-onset disabilities are discussed, emphasizing reduction in risks for aging-related chronic disease and secondary conditions, while promoting social participation and independence. However, indicators suggest that elevated risk factors for aging-related chronic diseases, including smoking, obesity, and inactivity, as well as barriers to prevention and the diminished social and economic situation of adults with disabilities are continuing impediments to successful aging that must be addressed. Increased provider awareness that people with early onset disabilities are aging and can age successfully and the integration of disability and aging services systems are transformative steps that will help adults with early onset disability to age more successfully.

Keywords: aging with disability, health promotion, socioeconomic status, social participation

Introduction

Numerous biological, behavioral, and social factors influence the aging process. However, behavioral factors are often viewed as highly important because they consistently predict onset of disability and death1 and are modifiable. Engaging in healthy behaviors is touted to add years of life and more quality to those years.2 Preventive health services and medical treatment have also been suggested to play a role in reducing disability and extending life.3

Models of successful aging2 consider how aging-related outcomes can be improved mainly by fostering healthier individual behaviors, such as avoiding smoking, alcohol abuse, unhealthy diets and inactivity, with a goal of deferring disability to the very end of the human lifespan4, or to put it another way, to delay or altogether avoid “aging into disability.” “Aging with a disability” refers to the aging process for the millions of individuals who have an early onset of disability at birth, in childhood or early adulthood. This paper addresses how well positioned people with early onset disabilities are to age successfully.

Many people with early onset disabilities are living longer than in the past, including those with Down Syndrome, spinal cord injury, traumatic brain injury, spina bifida, cerebral palsy and several other conditions,5-7 presumably due to improvements in medical treatment, rehabilitation, and social conditions whose roles remain unexplained. It has also been observed that some individuals with early-onset disabilities are developing secondary conditions and aging more rapidly than the general population, although the mechanisms generally are not very well understood5, 6, 8.

At this time, we must recognize that most children and adults with early onset disabilities will experience the benefits and challenges of aging in adulthood. Increased life expectancy enables more individuals with early-onset disabilities to obtain higher education and pursue employment careers that in turn help them to age more successfully. Yet individuals with early onset disabilities navigate the life course managing a primary condition (and those conditions diagnostically associated with a primary condition) and they face the risks of developing secondary conditions (the development of additional conditions due to having a primary condition).5 Many require health services and other long term services and supports that can be difficult to access in sufficient quality and quantity.9, 10 They are also at risk of falling between the cracks of an aging services system that is not well prepared to serve younger adults with disabilities and a disability services system that is not well prepared to help them to age successfully,11 Fortunately, this is starting to be corrected by integrating aging and disability services.12

The aim of this paper is to consider some key goals and indicators for the successful aging of adults with early onset disability. First, the size of the population aging with early-onset disabilities is not well-understood10 and is further considered. Second, popular models of successful aging have been developed with little attention to having an early-onset disability, as if aging successfully is out of the question for such individuals. Successful aging models in the context of having an early-onset disability are considered to help elucidate some of the goals of aging with a disability. Third, in order to age as successfully as those without disabilities, adults with early-onset disabilities should have equal or better values on indicators for successful aging than similar individuals without early-onset disabilities.. The inevitable conclusion is that adults with early-onset disabilities are not positioned to age as successfully as adults without disabilities and steps need to be taken to address these gaps.

Aging of individuals with early onset disabilities

A number of disabling conditions occur early in life and are not curable; individuals have them the rest of their lives. Some of these early onset conditions have shortened life substantially, but over the past several decades life expectancy has increased for those with spinal cord injury, traumatic brain injury, cerebral palsy, polio, and Down Syndrome and other intellectual disabilities. In the past, persons with Down Syndrome seldom reached adulthood but now they are living into midlife and beyond. Their mean age at death increased from 9 years in 1929 to above 50 years by the 1990s.13, 14 It has also been noted that the causes of death for older persons with intellectual disabilities (ID) are similar to the general population, with heart disease, cancer, and stroke being most common.15

The Institute of Medicine considered the evidence on aging with a disability for four primary conditions for which the evidence was deemed strongest: spinal cord injury, cerebral palsy, polio, and Down Syndrome. Evidence for the development of secondary conditions and premature aging was reviewed. A notable example of premature aging is the early development of Alzheimer’s among middle-aged adults with Down Syndrome. However, it is not clear to what extent that may be due to associated conditions (such as hypothyroidism which can cause memory problems), secondary conditions (such as memory loss due to prescribed drugs), or environmental factors. Further, while each primary condition has a specific set of issues and risks for secondary conditions and aging, individuals with disabilities also face the typical risk factors for aging as they live to midlife and beyond.

How many adults are aging with an early-onset disability?

Estimates of the overall population with disabilities in the United States come from censuses and surveys, but few provide any information to identify adults with early onset disabilities.10 Using the 1994 National Health Interview Survey on Disability (NHIS-D), Verbrugge and Yang 16 studied adults (ages 18+) who reported difficulties performing instrumental and basic activities of daily living (IADL, 6 items and ADL, 6 items) and selected physical activities (8 items—walking, , bending, standing, climbing stairs, lifting, reaching, grasping, and holding). Approximately 11.5 million adults reported difficulty with any of these items. For each item, persons were asked at what age the difficulty began. Selecting the earliest age of onset within each domain, thirty percent of adults of all ages reporting a basic ADL difficulty had an onset at 44 years of age or younger. The corresponding figures are 34 percent for those with an instrumental ADL difficulty and 39 percent for those with a physical activity difficulty. The results suggest that from one third to 40 percent of the adult population with disabilities had an onset of disability at or before age 44. However, these selected domains are not fully representative of all adults with early onset disabilities who are aging.

Another approach is to use the Harris survey on disability that collects information on age of onset. That is a telephone survey of 1,001 noninstitutionalized persons with disabilities last fielded in May and June of 2010. Disability is defined according to the broad definition used in the Americans with Disabilities Act, specifically whether the individual has any limitation in work, school, housework, or other activities due to chronic disease or impairments or considers him or her self, or is considered by others, to have a disability.17 In 2010, that definition was also applied to eleven other Harris surveys on other topics, yielding an estimated national prevalence of disability from 13-16 percent among adults ages 18 and older. From the survey on disability, 19% of all adults with any disability reported having an onset of disability from 0-19 years of age and 21% from 20-39 years of age. According to the 2010 National Health Interview Survey, there were 230 million adults ages 18 and older in the civilian noninstitutionalized population.18 Given the prevalence range mentioned above (13-16 percent), we can infer that from 12-15 million adults are aging with an early-onset disability that occurred prior to age 40. Combined with the results of Verbrugge and Yang, it is clear that adults who are aging with early-onset disabilities comprise a large population whether disability is measured by function or more broadly by complex activities.

Successful aging with disability

Populations are aging worldwide, some quite rapidly, with profound implications regarding the quality of life at older ages and the possible economic burden to societies. As a result, there is widespread interest in the promotion of successful aging. While there is not a consensus on exactly what successful aging means, the most basic idea is to live well into advanced ages and forestall the progression of aging-related diseases. Heart disease, cancer, and stroke are highly prevalent aging-related diseases that are associated with lifestyle choices. Both their onset and severity can be modified through smoking cessation, moderating alcohol consumption, eating healthier, and exercising.1, 2

A popular model is that of Rowe & Kahn2 who posit that successful aging is enjoying a low risk of disease and disease-related disability, maintaining high mental and physical functioning, and active engagement with life. The goal of this model is essentially to compress the onset of any disability to the end of the lifespan. It does not address how to age successfully with a disability that occurs early in life.

Baltes and Baltes 19 offer a human development model of successful aging whereby age-related decrements are considered a normal aspect of aging. Individuals do the best with the functioning they have and maintain it using various adaptation strategies. This model offers a more accommodating perspective for aging with an early onset disability.

Within the larger macro environment that presents both resources and constraints, persons with disabilities often adapt by “doing things differently,” using technology, personal assistance, and behavioral adaptations that best suit their needs and goals.20 Trieschmann7 offers a model of aging with a disability in which maintaining health and function is seen from the perspective of persons with disabilities as a “balancing act” that becomes more tenuous with age. Biological, psychological, and social variables affect this balance. It is also an adaptive model in which individuals learn health and functional survival skills and to function better in supportive environments. A key emphasis in Trieschmann’s model is maintaining productivity and meaningful social participation in order to age successfully.

While long term services and supports to people with disabilities are critical, providers need to be better informed about the health and functional challenges of aging with a disability.5 It has been observed that some seemingly best rehabilitation practices in the short term can turn out to be unsuccessful in the long term. The philosophy that emerged after WWII was that people with disabilities should be encouraged to work hard at achieving maximal function. However, it now appears that can cause problems as people with disabilities age. For example, it seems no longer a good practice to encourage people with CP to keep using limbs when that places them at risk of earlier degeneration as they age.6 Kemp and Mosqueda suggest that some reorientation in the field of rehabilitation is needed from the “use it or lose it” to a “conserve it and preserve it” approach at least for some conditions. The observation of faster aging in some disability groups also suggests a role for geriatric researchers and care professionals to extend their attention to this population. The need to manage a variety of primary conditions along with their associated conditions, risks of secondary conditions and premature aging amply describes the complexity that both research and practice must address in terms of aging with a disability.

Key goals for successful aging of people with disabilities

Health and wellness is a key goal for aging successfully. In the Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Improve the Health and Wellness of Persons with Disabilities 21 four goals are advanced:

establishing/maintaining good health and productivity.

early diagnosis and treatment

developing and maintaining healthy lifestyles

health care and supportive services sufficient to achieve independence

All of these goals can help adults aging with a disability to avoid secondary conditions and premature aging. In addition, the models of successful aging just discussed suggest key goals of living longer and living well with a disability, with optimal health and physical and cognitive function, optimal social interaction and productivity, and personal control and independence.19 To these I would add a goal of financial preparedness for reaching older ages. This is a substantial problem for persons aging with early-onset disabilities, especially those who have low levels of education16 and employment.22 Physical and social barriers to participation also impact the employment, careers, and the ability of adults aging with early-onset disabilities to save for periods when they cannot work.

Indicators for successful aging of people with disabilities

Key indicators for successful aging with a disability include length of life, physical and mental health and function, cognition, healthy lifestyles and behaviors, social interaction and productivity, independence, life satisfaction, access to quality health care and financial preparedness. These indicators have not been measured longitudinally as people with early-onset disabilities age compared to people without early-onset disabilities, but some cross sectional data are available.

Lifestyle and behavior

Altman and Bernstein23 provide several indicators of lifestyle behaviors of younger adults ages 18-44 with disabilities , using a large national household survey sample combining 5 years of the NHIS (2001-2005). This is a population that is aging with disabilities that have had an onset in childhood or early adulthood and provides some insight regarding how well they are positioned to age successfully compared to persons without disabilities. Disability was defined in a range from very broad to broad. The very broad category includes adults with difficulties in basic actions like walking or seeing, numbering 62.3 million adults, or 29.5 percent of the adult population. The broad classification includes adults with any complex activity limitations including working, social and leisure activities, self-care (ADL) and household maintenance activities (IADL). This group is a little less than half as large, numbering 30.1 million adults or 14.3 percent of all adults—a prevalence rate that lies within the Harris survey range of 13-16 percent mentioned earlier.

For the current purpose, among young adults ages 18-44, I compare the 7.4 million adults with complex activity limitations to the 90 million adults with no disabilities (with neither complex activity limitations nor difficulties in basic actions). Young adults with complex activity limitations rate their health much worse than those without disabilities (in fair or poor health: 37.9% vs. 2.4%, p<.001), and are more likely to be obese (29.8% vs. 17.8%, p<.001), to smoke (40.4% vs. 22.4%, p<.001), and to be inactive (47.7% vs. 32.8%, p<.001), but are less likely to be drinkers (53.0% vs. 67.0%, p<.001). These indicators suggest that young adults with disabilities have elevated risks for future cardiovascular disease, cancer, and arthritis, a situation previously noted by Iezzoni.9

At ages 18-44, adults with disabilities are young enough to have low levels of aging-related chronic diseases but they report a variety of impairments of bodily structure or function. A quarter have orthopedic impairments, a much higher percentage than those under age 18 (25.2% vs. 2.9%, p<.001).24 Other less common impairments are visual (2.2%), hearing (1.6%), intellectual disability (3.1%), and deformities of the back or limbs (2.7%). As for chronic health conditions, diseases of the musculoskeletal system collectively are common at 14.3 percent, although many of these diseases underlie the orthopedic impairments mentioned separately. They include degenerative intervertebral disc disorders (7.2%) and a smaller percentage with arthritis (3.6%). Mental illness (5.5%) and asthma (5.5%) are reported, as are diseases of the nervous system (6.4%), including epilepsy, migraines, and carpal tunnel syndrome. Some heart disease is reported (3.8%)—mostly involving hypertension. Congenital and perinatal conditions (2.9%) and effects of injuries and poisoning (2.6%) and cancer (1.2%) fill out the profile. Diagnostically, this is a population that appears relatively free of aging-related chronic disease although a small fraction may be showing early signs of aging-related chronic disease with some hypertensive heart disease, cancer, and arthritis mentioned. However, their elevated risk for chronic disease reduces their chances of successful aging.

Access to health care and long term services and supports (LTSS)

Young adults ages 18-44 with disabilities are more likely than those without disability to have a usual source of medical care (83.8% vs. 78.4%, p<.001) but slightly less likely for that to be at a doctor’s office (72.3% vs. 79.4%, p<.001).23 They are as likely to be uninsured (22%) and much less likely to have private insurance (40.1% vs. 71.0%, p<.001) but much more likely to be covered by Medicaid (32.8% vs. 5.4%, p<.001) and Medicare (11.3% vs. 0.2%, p<.001). As for access to preventive health care, they are more likely to have had a flu shot (for men, 21.4% vs. 12.4%; for women, 20.3% vs. 14.7%; both p<.001).

Adults with early-onset disabilities require timely access to early diagnosis and treatment to prevent secondary conditions and chronic diseases.5 Young women with disability are a little less likely than those without disability to have had a pap test in the past 3 years (79.5% vs. 84.3%, p<.001), which is recommended starting at age 21, but equally likely to have had a mammogram within the past 2 years (32%), which is recommended starting at age 40. While young adults with disabilities appear to have comparable access to health care, Iezzoni9 suggests that health professionals’ attitudes toward disability are often a problem, resulting in young adults not getting the right medical advice, with insufficient emphasis on health promotion and disease prevention.

Many of the 12-15 million adults with early-onset disabilities require long term services and supports (LTSS)—a major component of which is personal assistance with activities of daily living (IADL and ADL)—during their adult lifetimes to support their independence and participation and to remain in the community and avoid institutionalization. Developmental disabilities (DD) were defined in 1978 as any conditions that result in substantial functional limitations before the age of 22 and are likely to continue indefinitely (P.L. 95-602), implying a need for long term services and supports throughout an individual’s life.25 In a study using the 1994-95 NHIS-D, two-thirds of adults with DD received personal assistance in IADL or ADLs, or about 1 million adults.26 Some 583,000 persons with DD were being cared for by caregivers ages 55 and older, and 226,000 of the caregivers were aged 65 and older,27 which raises the issue of whether these individuals as they age will outlive their caregivers. LTSS are also required by adults with other disabilities. The observed unmet need for personal assistance services28 among people needing help with IADL and ADL and the fact that about half a million persons continue to be on waiting lists for home and community based services under Medicaid29 are indicators that this population is not receiving LTSS sufficient to achieve independence.

Work

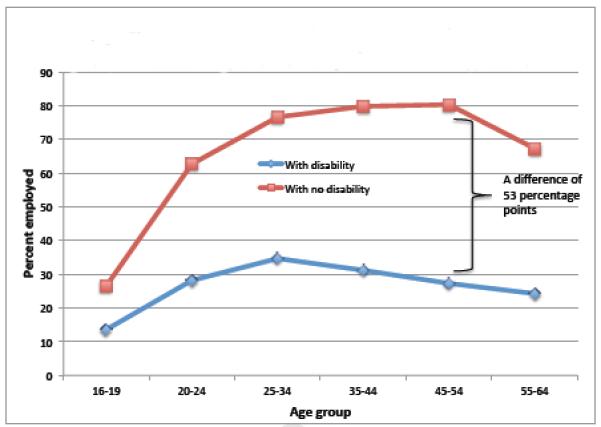

A key way that young adults participate in society is through employment, building careers that help them prepare financially for the years to come when their employment participation declines and their earned income diminishes. However, employment participation of people with disabilities is low at all ages and that has persisted over time.17 In 2012, according to the Current Population Survey (CPS), for adults with disabilities, employment rates are highest at ages 25-34 (34.7 %), and they tail off at higher ages (Figure 1). They never approach the rates for people without disabilities which continue to increase up to ages 45-54 to 80.5 percent, and then tail off as retirement age approaches.30 The largest gap occurs at ages 45-54 where the difference in employment rates reaches 53 percentage points (80.3% vs. 27.3%). These are prime earning years that many people with disabilities are left out of.

Figure 1.

Employment rates of people with and without disability, Current Population Survey, 2012

Some reasons for the low employment rate of adults with disabilities include lower educational attainment and poor health, but employment discrimination, lack of suitable jobs, and fear of losing benefits are reasons that people with disabilities often provide.17 Nevertheless, lower rates of employment set up young adults with disabilities for a life of relying on income transfer programs that on average leaves them in poverty or close to poverty.31

As for other types of participation, according to the Kessler/Harris survey of 2010,17 among young adults ages 18-29, there was no difference between those with and without disabilities in socializing with close friends, relatives, or neighbors at least twice a month (94% vs. 91%), but at ages 30-44, people with disabilities are somewhat less likely (83% vs. 94%) to socialize. Younger adults with disabilities are also less likely to go to restaurants than those without disabilities (ages 18-29: 57% vs. 70%; ages 30-44: 47% vs. 81%), but this indicator also reflects the lower affordability of eating out for people with disabilities,

Income and financial preparedness

Adults with disabilities experience a vicious cycle. At the ages when most adults without disabilities are maximizing employment and earnings, adults with disabilities earn far less, with more part-time work and lower wages,32 reducing individual and family income.

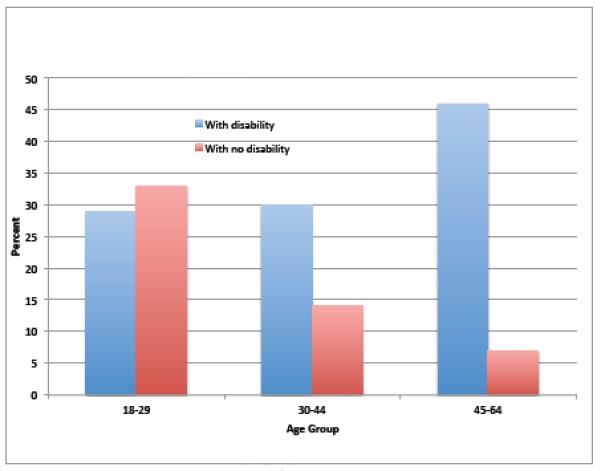

At young ages, individuals with and without disabilities are equally likely to have low family income (Figure 2), but by ages 45-64, 46% of individuals with disabilities have family incomes less than $15,000 a year, compared to 7% of individuals without disability.17 Adults without disabilities show a different trajectory, appearing to earn their way to higher income. This may be somewhat misleading since it also reflects the incidence of disability at older ages among persons and families with low income. Nevertheless, adults with disabilities live a financially precarious existence—only a third could support themselves for 3 months if they lost income,17 reflecting low savings. The lack of financial preparedness increases with age, which is not a recipe for successful aging.

Figure 2.

Percentage with family income under $15,000, Harris Survey, 2010

Life satisfaction

The Harris surveys have tracked life satisfaction of adults with disabilities since 1986, and they report consistently less satisfaction with their lives than people without disabilities. In 2010, the levels of being very or somewhat satisfied are 62% and 88% respectively for all ages.

At ages 18-29, 70% of adults with disabilities are satisfied compared to 89% of those with no disability. At ages 30-44, satisfaction drops to 57% for those with disabilities, but remains the same for those with no disabilities (87%). At ages 45-64, satisfaction increases to 69 percent for persons with disabilities, but sill is lower than for those without disabilities (86%) . It is not clear what the drop in satisfaction at ages 30-44 is due to, but almost 38 percent of persons with disabilities in that age group report being very or somewhat dissatisfied, which may indicate problems in adapting to midlife that may not be conducive to successful aging.

Conclusion

At 12-15 million persons, the population of adults aging with early-onset disabilities is large and will grow. There remains much to be done to help this population age more successfully. Key goals include improving their health, function, productivity, and satisfaction, and reducing their elevated risks for aging-related chronic diseases. The younger population of adults with early onset disabilities has low levels of aging-related chronic disease, but shows elevated risk factors for acquiring them, with rates of smoking, obesity, and inactivity about twice as high as adults without disabilities. Indeed, 40 percent of adults with disabilities who are 18-44 smoke. It is not a profile conducive to successful aging and interventions are needed to reduce this risk.

Improving access to health care and long term supportive services is crucial to help adults with early onset disabilities avoid secondary conditions and chronic diseases, to achieve independence, and to age in place. Low levels of education, employment, and earnings also place this group in a precarious situation with little chance to prepare financially for older ages. Improving the ability of people with early onset disabilities to accumulate assets33 would help their financial prospects of aging successfully. While 20 percent of young adults with disabilities are uninsured, the Affordable Care Act should help to reduce that percentage as it is implemented. Reducing barriers to preventive health care and changing provider attitudes toward health promotion and disease prevention is also needed.

While much improvement is required, by acknowledging and focusing on the potential for successful aging of adults with early-onset disabilities, attention can be propelled longer term to more effectively promote their health, functioning, and social and economic well-being. Professionals’ attitudes toward health promotion and risk reduction might be expected to become more optimistic if they are made aware of the potential for aging with a disability. When combined with an integrated disability and aging services system, that would be highly transformative for adults with early-onset disabilities to age more successfully.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures:

This paper was prepared with funding from the University of Syracuse the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (grant #H133B080002). An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Conference on “Aging with Disability: Demographic, Social, and Policy Considerations," May 17-18, 2012, in Washington, DC.

References

- 1.Chakravarty EF, Hubert HB, Krishnan E, Bruce BB, Lingala VB, Fries JF. Lifestyle risk factors predict disability and death in healthy aging adults. Am J Med. 2012 Feb;125(2):190–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rowe JW, Kahn RL. Successful aging. xv. Dell Pub.; New York: 1999. p. 265. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manton KG. Recent declines in chronic disability in the elderly U.S. population: risk factors and future dynamics. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:91–113. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fries JF. The compression of morbidity. Milbank Mem Fund Q Health Soc. 1983;61(3):397–419. Summer. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Field MJ, Jette AM, editors. The future of disability in America. xxv. National Academies Press; Washington, D.C.: 2007. Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Committee on Disability in America; p. 592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kemp B, Mosqueda LA. Aging with a disability : what the clinician needs to know. xiv. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore: 2004. p. 307. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trieschmann RB. Aging with a disability. x. Demos Publications; New York: 1987. p. 148. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Groah SL, Charlifue S, Tate D, Jensen MP, Molton IR, Forchheimer M, et al. Spinal cord injury and aging: challenges and recommendations for future research. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation / Association of Academic Physiatrists. 2012 Jan;91(1):80–93. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e31821f70bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iezzoni LI. Eliminating health and health care disparities among the growing population of people with disabilities. Health affairs. 2011 Oct;30(10):1947–54. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Washko MM, Campbell M, Tilly J. Accelerating the translation of research into practice in long term services and supports: a critical need for federal infrastructure at the nexus of aging and disability. Journal of gerontological social work. 2012;55(2):112–25. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2011.642471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Putnam M. Perceptions of difference between aging and disability service systems consumers: implications for policy initiatives to rebalance long-term care. Journal of gerontological social work. 2011 Apr;54(3):325–42. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2010.543263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Shaunessy CV. Aging and Disability Resource Centers Can Help Consumers Navigate the Maze of Long-Term Services and Supports. Generations. 2011;35(1):64–8. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baird PA, Sadovnick AD. Life expectancy in Down syndrome adults. Lancet. 1988 Dec 10;2(8624):1354–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)90881-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang Q, Rasmussen SA, Friedman JM. Mortality associated with Down's syndrome in the USA from 1983 to 1997: a population-based study. Lancet. 2002 Mar 23;359(9311):1019–25. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08092-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janicki MP, Dalton AJ, Henderson CM, Davidson PW. Mortality and morbidity among older adults with intellectual disability: health services considerations. Disabil Rehabil. 1999 May-Jun;5-6:284–94. doi: 10.1080/096382899297710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verbrugge LM, Yang L-s. Aging with disability and disability with aging. Journal of Disability Policy Studies. 2002;12(4):253–67. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kessler Foundation/National Organization on Disability. The ADA, 20 years later. Kessler Foundation/NOD survey of Americans with disabilities. 2010 http://www.2010disabilitysurveys.org/pdfs/surveyresults.pdf. Accessed June 26, 2013. Washington: Author.

- 18.Schiller JS, Lucas JW, Ward BW, JA P. Summary Health Statistics for U.S. Adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2010. Vital Health Stat 10. 2011 Dec;252:1–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baltes PB, Baltes MM. Successful aging : perspectives from the behavioral sciences. xv. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge [England] ; New York: 1990. p. 397. [Google Scholar]

- 20.LaPlante M, Kaye HS, Mullan JT, Wong A. Initial development of the Disability and Activity Impact Screener (DAIS): An example of qualitative measurement discovery. In: Kroll T, Keer D, Placek P, Cyril J, Hendershot GE, editors. Towards Best Practices for Surveying People With Disabilities. Nova Science Publishers, Inc.; New York: 2007. pp. 147–64. [Google Scholar]

- 21.United States. Public Health Service Office of the Surgeon General. The Surgeon General's Call to Action to Improve the Health and Wellness of Persons with Disabilities. 2005 http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/calls/disabilities/index.html. Accessed June 26, 2013. Rockville, MD: Author. [PubMed]

- 22.Brault M. Americans with Disabilities: 2010. Current Population Reports. 2012;P70(131) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Altman B, Bernstein A. Disability and health in the United States, 2001-2005. 2008 http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/misc/disability2001-2005.pdf. Accessed June 26, 2103. Hyattsville, MD: Dept. of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics;

- 24.LaPlante MP, Carlson D. Disability in the United States: Prevalence and Causes, 1992. National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research; Washington, DC: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boulet SL, Boyle CA, Schieve LA. Health care use and health and functional impact of developmental disabilities among US children, 1997-2005. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009 Jan;163(1):19–26. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2008.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larson S, Lakin C, Anderson L, Kwak N. Characteristics of and Service Use by Persons with MR/DD Living in Their Own Homes or With Family Members: NHIS-D Analysis. 2001 MR/DD Data Brief, Series 3, Number 1. www.rtc.umn.edu/docs/dddb3-1.pdf Accessed June 26, 2013. Minneapolis, MN: Institute on Community Integration, University of Minnesota.

- 27.Byun S-y, Anderson L, Larson SA, Lakin KC. Characteristics of Aging Caregivers in the NHIS-D. 2006 DD Data Brief, Series 8, Number 1. http://rtc.umn.edu/docs/dddb8-1.pdf. Accessed June 26, 2013. Minneapolis, MN: Institute on Community Integration, University of Minnesota.

- 28.LaPlante MP, Kaye HS, Kang T, Harrington C. Unmet need for personal assistance services: estimating the shortfall in hours of help and adverse consequences. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2004 Mar;59(2):S98–S108. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.2.s98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ng T, Harrington C, O'Malley M. Kaiser Family Foundation, Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured; Washington, DC: 2008. Medicaid Home and Community-Based Service Programs: Data Update. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Persons With A Disability: Labor Force Characteristics — 2012. Washington, DC: 2013. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Press release dated Wednesday, June 12, 2013. http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/disabl.pdf Accessed June 26, 2013. . [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stapleton DC, O'Day BL, Livermore GA, Imparato AJ. Dismantling the poverty trap: disability policy for the twenty-first century. Milbank Q. 2006;84(4):701–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2006.00465.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brault M. Current Population Reports. U.S. Bureau of the Census; Washington, D.C.: 2008. Americans with Disabilities: 2005; pp. P70–117. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ball P, Morris M, Hartnette J, Blanck P. Breaking the Cycle of Poverty: Asset Accumulation by People with Disabilities. Disability Studies Quarterly. 2006;26(1) [Google Scholar]