Abstract

Because DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) inhibitors like azacytidine and decitabine are known to be effective in the clinic for diseases like myelodysplastic syndromes that may result in part from transcriptional dysregulation due to epigenetic changes, there is interest in developing novel DNMT inhibitors that would be more effective and less toxic. The effects of one such agent, zebularine, which inhibits DNMT and cytidine deaminase, were assessed in two human breast cancer cell lines, MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7. Zebularine treatment inhibited cell growth in a dose and time dependent manner with an IC-50 of ∼100 μM and 150 μM in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells, respectively, on 96 h exposure. This was associated with increased expression of p21, decreased expression of cyclin-D, and induction of S-phase arrest. At high doses zebularine induced changes in apoptotic proteins in a cell line specific manner manifested by alteration in caspase-3, Bax, Bcl2 and PARP cleavage. Like other DNMT inhibitors, zebularine decreased expression of DNMTs post transcriptionally as well as expression of other epigenetic regulators like methyl CpG binding proteins and global acetyl H3 and H4 protein levels. Its capacity to reexpress epigenetically silenced genes in human breast cancer cells at low doses was confirmed by its ability to induce expression of estrogen and progesterone receptor mRNA in association with changes suggestive of active chromatin at the ER promoter as evidenced by ChIP. Finally, its effect in combination with other DNMT or HDAC inhibitors like decitabine or vorinostat was explored. The combination of 50 μM zebularine with decitabine or vorinostat significantly inhibited cell proliferation and colony formation in MDA-MB-231 cells compared with either drug alone. These findings suggest that zebularine is an effective DNMT inhibitor and demethylating agent in human breast cancer cell lines and potentiates the effects of other epigenetic therapeutics like decitabine and vorinostat.

Keywords: DNA methyltransferase, Zebularine, Breast cancer, Epigenetic, Estrogen receptor

Introduction

Breast cancer results from an accumulation of genetic and epigenetic events. Multiple mutations have been identified in primary breast cancers [1] but such changes are difficult to overcome. In contrast, most epigenetic modifications are post-transcriptional, reversible events that do not target gene sequence [2, 3], and inhibition of these mechanisms could theoretically be advantageous in the treatment of breast cancer. As a consequence the role of epigenetic regulators like histone deacetylase (HDAC) and DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) inhibitors as treatment for breast cancer is under evaluation.

The two well characterized and clinically relevant DNMT inhibitors, azacytidine (aza) and decitabine (5-azaDc) are nucleoside analogue mechanism-based inhibitors. They substitute for cytosine residues in DNA during replication and inhibit DNMT activity through covalent binding to the DNMT enzymes, resulting in reduced genomic DNA methylation [4–7]. Although effective against certain hematopoietic disorders, these drugs have some toxicity both in vitro and in vivo and are unstable in neutral solutions [8, 9]. Further, deamination of these analogues by cytidine deaminases results in their inactivation. Hence a nontoxic, highly stable, effective DNMT inhibitor would be an ideal epigenetic therapeutic.

One such putative agent is zebularine, a cytidine analog containing a 2-(1H)-pyrimidinone ring that was originally developed as a cytidine deaminase inhibitor [10–12] to prevent deamination of nucleoside analogues. Zebularine is also a versatile starting material for the synthesis of complex nucleosides and is a mechanism based DNA cytosine methyltransferase inhibitor [13]. It acts primarily as a trap for DNMT protein by forming tight covalent complexes between DNMT protein and zebularine-substituted DNA [14]. In contrast to other DNMT inhibitors, it has low toxicity in most cell lines tested [15–17] and is quite stable with a half-life of 510 h at pH 7.4 [13]. Because of its low toxicity, continuous administration of effective doses of zebularine alone or in combination with other DNMT inhibitors is feasible and this can result in the enhanced reexpression of epigenetically silenced genes in cancer cells [18].

Several preclinical studies have evaluated zebularine as a possible therapeutic in cancer cell lines. Zebularine preferentially incorporates into DNA, leading to cell growth inhibition and increased expression of cell cycle regulatory genes in cancer cell lines compared with normal fibroblasts [19]. It was also found to reactivate expression of several abnormally silenced methylated genes like p16 in T24, HCT15, CFPAC-1, SW48 and HT-29 cells [19]; E-cadherin in Akata cells [17]; and p15INK4B in AML 193 cells [16]. However, its effects on breast cancer cells have not been reported. Here, the demethylating and cytotoxic effects of zebularine in human breast cancer cell lines were evaluated and the utility of zebularine in conjunction with other epigenetic modifiers was explored.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Zebularine was a kind gift from Dr. Victor Marquez (National Cancer Institute). DNMT1 antibody was provided by Dr. William Nelson, Johns Hopkins University [20]. Antibodies to Bcl2; Bax; caspases 3, 8 and 9; cyclins B and D; p21; and p27 were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). Antibodies against acetylated H3 and H4 and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) were obtained from Upstate Biotechnology, Inc. (Lake Placid, NY) while DNMT3a and DNMT3b antibodies were from Affinity BioReagents (Golden, CO) and Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO), respectively.

Cell lines and culture

Human breast cancer cell lines MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 were maintained at 37°C, 5% CO2 in DMEM supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, Logan, UT) and 2 μmol/l L-alanyl-L-glutamine (Mediatech, Herndon, VA). For treatment, cells were seeded at a density of 3 × 105 per 100-mm tissue culture dish in phenol red-free DMEM supplemented with 5% charcoal-treated FBS (estrogen stripped medium) (Hyclone, Logan, UT). After 24 h, the estrogen stripped medium was changed to estrogen stripped medium containing zebularine for 96 h.

Cell proliferation assays

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazoliumbro mide (MTT) assay was performed as previously described to evaluate the effects of different concentrations of zebularine for 24, 48, 72, or 96 h [21]. The results of MTT assays were validated by comparison with conventional cell counting using coulter counter. For combination study cells were treated with 50 μM zebularine, 1 μM 5-azaDc and 2.5 μM vorinostat (suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid or SAHA).

Flow cytometry

For flow cytometry MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells plated at a cell density of 100,000 cells in 10-cm culture dishes were treated with different doses of zebularine for 96 h. Cells were collected by trypsinization, washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline, fixed with 4.44% formaldehyde (Sigma), and stained with Hoechst 33258 (Sigma). BD-LSR (BD Biosciences) was used to perform FACS, and the cell cycle was analyzed using Cell-Quest software (BD Biosciences).

Colony formation assay

After trypsinization, single cell suspensions of MDA-MB-231 cells (200 cells/well) were plated in 6-well plates. Media was replaced with drug containing media 24 h later and then every 3 days for the entire period of study. After 10 days the colonies were rinsed with PBS, fixed, and stained with crystal violet solution [22]. Assays were performed in triplicate for each independent experiment.

Western blot and histone analysis

MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells treated with different doses of zebularine for 96 h were washed with ice-cold PBS, harvested by gentle scraping, and lysed with protein extraction buffer containing 150 mmol/l NaCl, 10 mmol/l Tris (pH 7.2), 5 mmol/l ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 0.1% Triton X-100, 5% glycerol, and 2% SDS. Samples were electrophoresed on 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes for hybridization with primary antibodies followed by peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse or goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:5,000; DAKO Corp., Carpinteria, CA) and enhanced chemiluminescence staining (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). The expression of β-actin was used as control.

Histone proteins from cells treated with zebularine were isolated according to previously published protocols [23]. From control and zebularine-treated cells, about 3–5 μg of histone protein was analyzed by Western blotting using anti-acetyl histone3 (H3) and anti-acetyl histone4 (H4) antibodies (1:1,000; Upstate Biochemical, Lake Placid, NY) and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:2,000).

Band intensity from scanned images of western blots was calculated by densitometric analysis using Image J software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/). Analysis was done on at least three replicates for each experiment.

Reverse transcription and PCR

RNA was harvested from zebularine-treated MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells by Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) as previously described [24]. Reverse transcription was done with 3 μg RNA using MMLV reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) and oligo dT primers at 42C for 1 h. Conventional PCR was performed on cDNA samples with gene specific primers, and the PCR products were resolved on 2% agarose gels and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. The primers used were ER α S: GCA CCC TGA AGT CTC TGG AA and AS: TGG CTA AAG TGG TGC ATG AT; PR S: TCA TTA CCT CAG AAG ATT TGT TTA ATC and AS: TGA TCT ATG CAG GAC TAG ACA A; progesterone receptor (PR) S: TCATT ACCTCAGAAGATTTGTTTAATC and AS: TGATCT ATGCAGGACTAGACAA; actin S: ACC ATG GAT GAT GAT ATC GC and AS: ACA TGG CTG GGG TGT TGA AG.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

Chromatin immunoprecipitation was done using previously published methods [25] with minor modifications. Chromatin samples from MDA-MB-231 cells treated with 100 or 200 μM zebularine for 96 h were sonicated on ice thrice for 15 s. The samples were immunoprecipitated with specific antibodies. The immunoprecipitated DNA was ethanol precipitated and resuspended in 30 μl TE buffer. The ER promoter was analyzed using previously published primers [25]. MDA-MB-231 cells treated with 2.5 μM 5-azaDc were used as a positive control.

Data analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SE for each treatment group. One-way ANOVA was used to compare the differences between control and treatment groups. When significant, ANOVA was, followed by a post-hoc test (Tukeys HSD or Dunnets) as required. Significance was set at α = 0.05. All analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, Inc. La Jolla, CA).

Results

Zebularine inhibits human breast cancer cell growth in a dose and time dependent manner

Human breast cancer cell lines MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 representing estrogen receptor α (ER)-positive and -negative phenotypes, respectively, were utilized for this study. In addition, numerous studies including our own have documented that expression of multiple genes including ER is epigenetically silenced in MDA-MB-231 cells and the underlying mechanisms have been extensively explored, making this cell line particularly informative for the evaluation of zebularine.

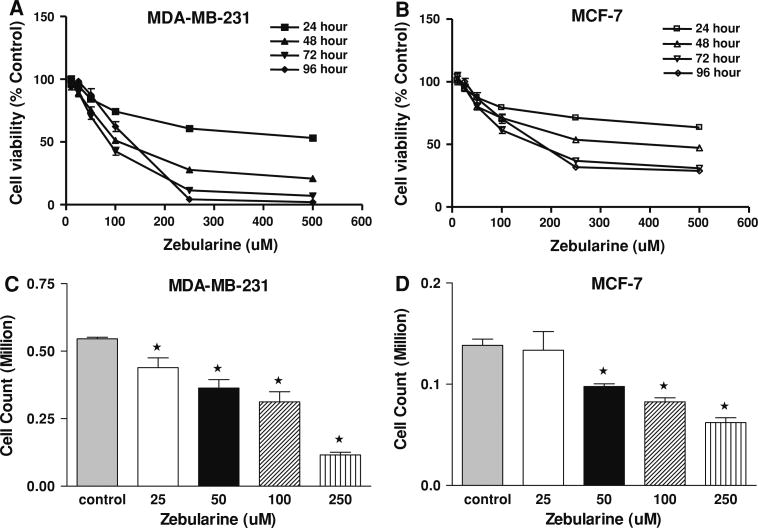

The effect of zebularine (25–500 μM) on cell proliferation after 24, 48, 72 and 96 h of exposure was assessed by MTT assay (Fig. 1). MDA-MB-231 cells were more sensitive to zebularine treatment with a significant decrease in cell proliferation at most doses tested. The IC50s were >500, 150, 99 and 88 μM, respectively, at 24, 48, 72, and 96 h of exposure (Fig. 1a). MCF-7 cells were less sensitive to zebularine with IC50 s of >500 μM, 426, 180 and 149 μM at 24, 48, 72 and 96 h, respectively, (Fig. 1). These results suggest that ER-negative MDA-MB-231 cells are more susceptible to zebularine mediated cytotoxicity than ER-positive MCF-7 cells. The differential effects of zebularine observed in the MTT assay were confirmed by cell count analysis where the IC50 for zebularine for 96 h was 130 μM for MDA-MB-231 cells and 195 μM for MCF-7 cells.

Fig. 1.

Zebularine inhibits cell proliferation in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells in a dose- and time-dependent manner. MDA-MB-231 (a) and MCF-7 (b) cells were treated with varying doses of zebularine for 24, 48 72 and 96 h and assayed by MTT assay. Absorbance was read at 540 nM. Results were confirmed by cell counts by coulter particle counting of MDA-MB-231 (c) and MCF-7 cells (d) after 96 h of treatment with different doses of zebularine. Data represent one of three independent experiments done in quadruplicate that gave similar results. * P < 0.05

Zebularine induces S phase arrest in both MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cell lines and alters the expression of cell cycle regulatory proteins

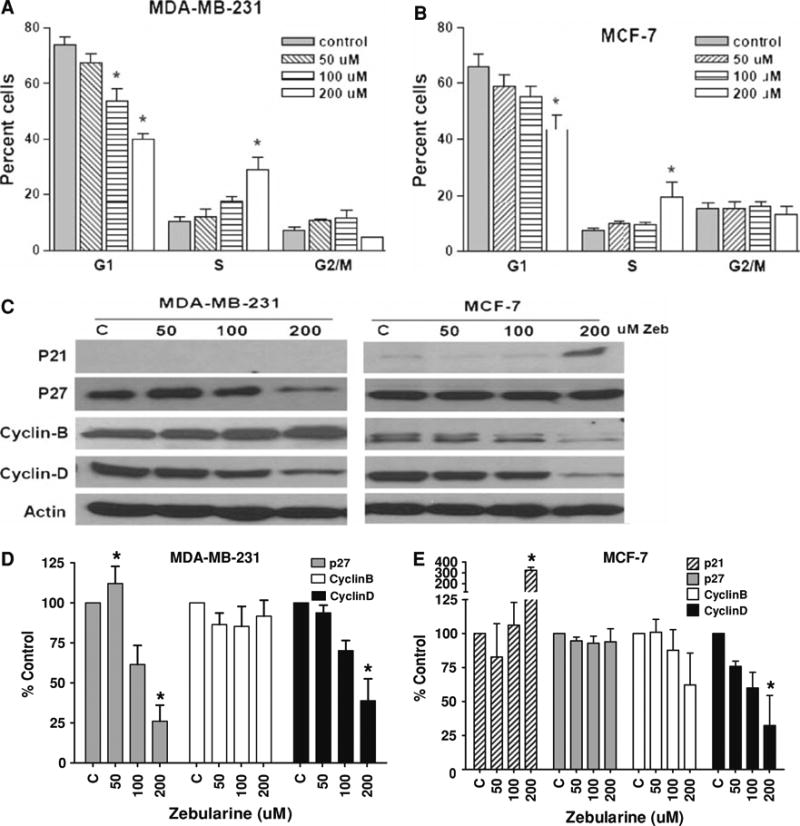

As expected for a nucleoside analogue, zebularine induced an S-phase arrest in both MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells (Fig. 2a, b). Flow cytometric analysis of both cell lines treated with different doses of zebularine (50, 100 and 200 μM) for 96 h showed a significant decrease in percentage of cells in G1 phase at both 100 and 200 μM zebularine in MDA-MB-231 cells and 200 μM in MCF-7 cells. Further, an increase in percentage of cells in S-phase consistent with S-phase arrest was observed at the highest dose of 200 μM in both cell lines. Because of these changes, the effect of zebularine on expression of critical cell cycle proteins was assessed. As previously reported [26, 27], p21 protein expression was essentially undetectable in MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 2c) and treatment with zebularine did not alter its expression. However, zebularine decreased p27 protein expression in a dose dependent fashion with a significant decrease at the highest dose (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2c, d). In contrast, zebularine treatment of MCF-7 cells was associated with enhanced p21 expression at 200 μM without significant alteration in P27 expression (Fig. 2c, e). A differential pattern of zebularine effects on cyclin B and D proteins was also observed. In MDA-MB-231 cells, 200 μM zebularine led to significant decrease in cyclin D but not cyclin B protein expression whereas expression of both cyclin proteins was significantly diminished with 200 μM zebularine in MCF-7 cells (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2c–e). These results suggest that zebularine treatment of MCF-7 cells results in enhanced expression of cyclin dependent kinase inhibitors like p21, and decreased expression of cyclins B and D, halting the transition of cells from S to G2 phase and resulting in S-phase arrest. However, in MDA-MB-231 cells, an S-phase arrest appears to be regulated mainly by down regulation of cyclin D.

Fig. 2.

Zebularine induces S-phase arrest and alters the expression of cell cycle regulators in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells in a dose-dependent manner. MDA-MB-231 (a) and MCF-7 (b) cells were treated with 50, 100 or 200 μM zebularine for 96 h. Cells were harvested and analyzed by fluorescence activated cell sorting as described in “Materials and Methods”. Percentage cells in each phase of the cell cycle at a given dose are represented. Bars represent mean of three independent experiments each done in triplicate. * P < 0.05. c Equal amounts of lysates from MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells treated with 50, 100 or 200 μM zebularine for 96 h were immunoblotted with antibodies against key cell cycle regulatory proteins as described in “Materials and Methods”. Representative blots from one of three experiments that gave similar results are shown. Blots from three experiments were quantified densitometrically and mean ± standard deviation is shown for MDA-MB-231 (d) and MCF-7 (e). Asterisk (*) indicates significant difference from control (ANOVA and Tukey's HSD, P < 0.05)

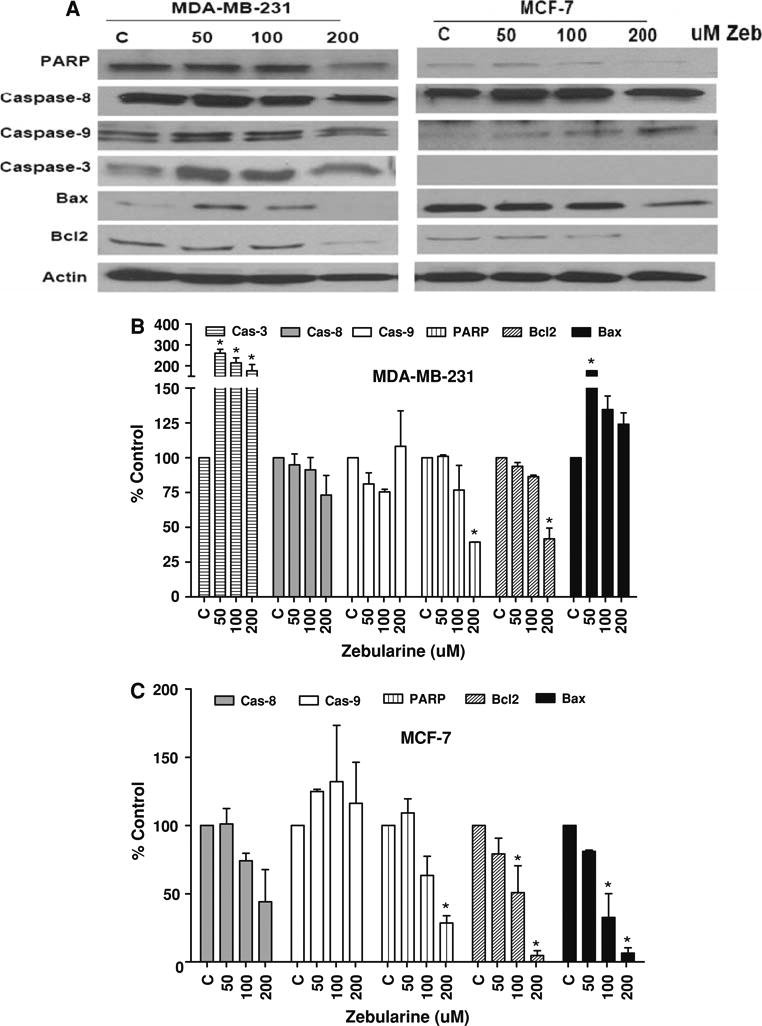

Zebularine induces apoptotic cell death in breast cancer cells

The possibility that zebularine might induce apoptotic cell death was explored by western blot analysis of key apoptosis-associated proteins. In both MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells, treatment with increased doses of zebularine was associated with enhanced cleavage of PARP (116 kDA). PARP cleavage was significant at the two highest doses tested in MCF-7 cells but only at the highest dose in MDA-MB-231 cells (P < 0.05). Increased expression of caspase 3 without significant alteration of caspase 8 or 9 protein expression was observed in MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 3a, b). In contrast, enhanced expression of caspase 9 and cleavage of PARP were observed in MCF-7 cells that are known to lack caspase 3 expression (Fig. 3a, c). Expression of anti-apoptotic Bcl2 protein was reduced in a dose-dependent manner in both cell lines as was Bax expression in MCF-7 cells. In contrast, Bax expression was significantly upregulated at 50 μM (P < 0.05), indicating that Bax may be an early response protein, upon zebularine treatment in MDA-MB-231 cells. Together these findings suggest that zebularine treatment of MCF-7 cells induces apoptosis through the intrinsic mitochondrial pathway while zebularine treatment triggers apoptosis via both the intrinsic and extrinsic pathways in MDA-MB-231 cells.

Fig. 3.

Zebularine induces apoptosis in a cell-type specific manner in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells. a MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells were treated with 50, 100 or 200 μM zebularine for 96 h. Equal amounts of cell lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies specific for key apoptosis regulatory proteins as described in “Materials and Methods”. Actin protein was blotted as a loading control. Representative blots from one of three experiments that gave similar results are shown. Blots from all three experiments were quantified densitometrically and mean ± standard deviation is shown for MDA-MB-231 (b) and MCF-7 (c). Asterisk (*) indicates significant difference from control (ANOVA and Tukey's HSD, P < 0.05)

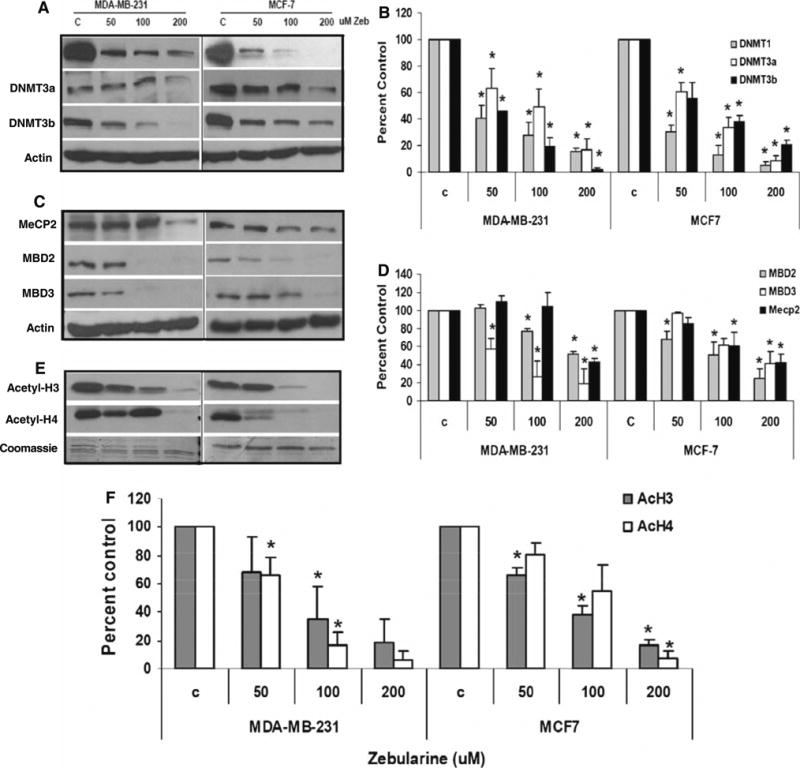

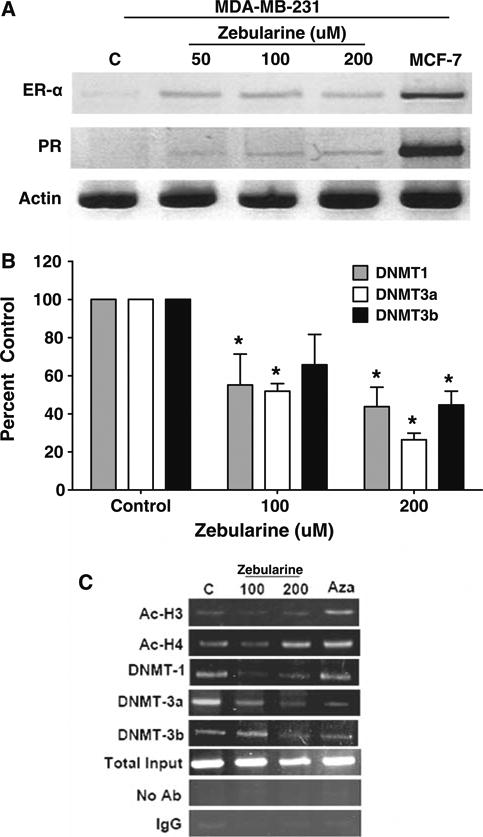

Zebularine inhibits the expression of epigenetic regulators

Because of zebularine's activity as a DNMT inhibitor in other model systems, its effect on expression of DNMTs in breast cancer cells was examined (Fig. 4). As expected, zebularine treatment was associated with a statistically significant dose-dependent depletion of DNMT1, DNMT3a, and DNMT3b proteins in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 4a, b) even at the lowest dose tested (50 μM). A nonquantititative analysis of mRNA levels for each of the three DNMT by RT-PCR did not show any change in mRNA expression (data not shown), supporting other studies suggesting that its primary mode of action is posttranscriptional through trapping of DNMT proteins by zebularine incorporated into DNA.

Fig. 4.

Zebularine inhibits protein expression of epigenetic regulators in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells. MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells were treated with 50, 100 or 200 μM zebularine for 96 h. Equal amounts of protein lysates (a, c) or histone protein (e) were fractionated on 12% SDS-PAGE gels, transferred to PVDF membrane, and immunoblotted with specific antibodies as described in “Materials and Methods”. Actin protein was blotted as a loading control while Coomassie staining was used as loading control for histones (c). Representative blots from one of three experiments that gave similar results are shown. Blots from all three experiments were quantified densitometrically and mean ± standard deviation is shown for changes from control induced by zebularine in DNA methyltransferases (b), methyl CpG binding proteins (d) and acetylated histones (f). Asterisk (*) indicates significant difference from control (ANOVA and Tukey's HSD, P < 0.05)

Because of the importance of the methyl CpG binding domain proteins (MBDs) in transcriptional repressor complexes, the impact of zebularine treatment on these proteins was also evaluated. While a significant dose dependent decrease in MBD2 levels was observed in MCF-7 cells at the lowest dose, such a decrease was evident only at doses >100 μM in MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 4c, d). Conversely, MBD3 protein expression was very sensitive to zebularine treatment in MDA-MB-231 cells even at the lowest dose, while its expression was decreased only at 200 μM in MCF-7 cells. Effect of zebularine treatment on MeCP2 expression was cell line specific with greater sensitivity in MCF-7 cells than MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 4c, d).

As zebularine decreased expression of multiple proteins associated with transcriptional repression and induced a cell cycle arrest, we speculated that alterations in histone acetylation, a hallmark of transcriptional activity, might be elicited. Indeed, zebularine treatment resulted in dose-dependent inhibition of global acetyl H3 and acetyl H4 expression in both the cell lines (Fig. 4e, f). Zebularine treatment had no effect on histone methylation of dimethylated H3K9, or dimethylated H3K4 in either cell line (data not shown).

Zebularine reexpresses ER in ER negative cell lines

Given its properties and postulated mechanisms of action, a key question is whether zebularine can alter expression of epigenetically silenced genes. One such gene is estrogen receptor alpha (ESR1 or ER), an important regulator of breast cancer growth and a target for treatment. Because earlier studies have shown that epigenetic silencing associated with hypermethylation of the promoter region is one of the principal mechanisms to silence ER expression in ER-negative breast cancer cells in culture, the ability of zebularine to reexpress ER in MDA-MB-231 cells was evaluated. Zebularine treatment was associated with reexpression of ER mRNA in MDA-MB-231 cells, even at doses as low as 50 μM after 96 h exposure (Fig. 5a). This appears to have functional consequences as reexpression of the ER target gene, progesterone receptor (PR) was also noted. However, ER-beta gene expression was unaltered at all doses tested (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Zebularine reactivates functional ER-α expression in MDA-MB-231 cells. a RNA was isolated from MDA-MB-231 cells treated with 50, 100 or 200 μM zebularine for 96 h by Trizol reagent and reverse transcription was done with 3 μg RNA. PCR was performed using cDNA with specific primers as described in “Materials and Methods”. b MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with zebularine or 2.5 μM decitabine for 96 h and chromatin immunoprecipitation was performed. PCR amplification was performed with primers encompassing the NotI site in the ER gene. Chromatin DNA before immunoprecipitation (input) was PCR amplified to confirm equal loading. Data from three experiments were quantified for zebularine treatment and represented (b, c)

To understand the molecular changes that are associated with the transcriptionally active ER promoter after zebularine treatment of MDA-MB-231 cells, chromatin immunoprecipitation assays were undertaken using primers in the ER promoter region. As shown in Fig. 5b, treatment of MDA-MB-231 cells with zebularine significantly elevated the association of acetylated H4 with the ER promoter while DNMT1, DNMT3a, and DNMT3b were released from the ER promoter. As a positive control, the cells were treated with 2.5 μM of the classic DNMT inhibitor, 5-azaDc for 96 h and similar changes were noted after treatment. These results are consistent with zebularine induction of changes at the ER promoter that favor gene transcription.

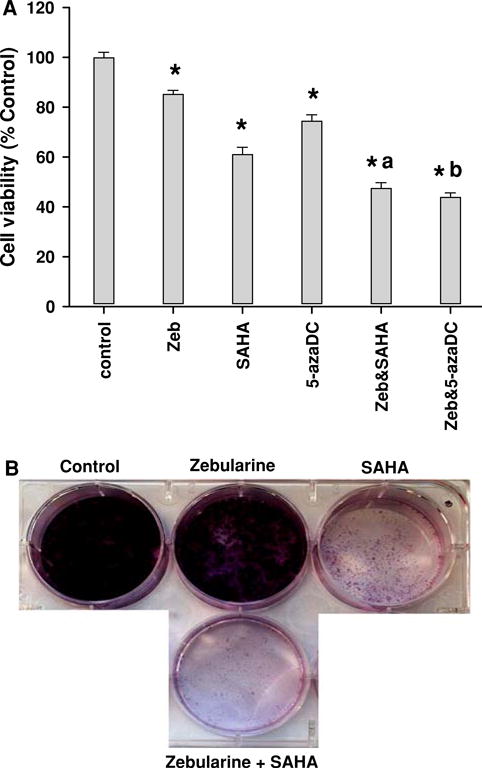

Zebularine potentiates the inhibitory effect of other epigenetic therapeutics on cell proliferation and colony formation

This study convincingly provides evidence that as with other cancers, at low doses zebularine is an effective demethylating agent, with minimal toxicity. We next asked whether zebularine can act in concert with other epigenetic modifiers. The combination of low dose zebularine (50 μM) with 1 μM decitabine or 2.5 μM vorinostat led to decreased MDA-MB-231 cell proliferation compared with either drug alone (P < 0.05) (Fig. 6a).

Fig. 6.

Low dose zebularine potentiates the inhibitory effects of DNMT and HDAC inhibitors on cell proliferation and colony formation. MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with 50 μM zebularine, 1 μM 5-azaDc or 2.5 μM SAHA alone or in combination. Effect on cell proliferation was assayed by MTT as described in “Materials and Methods”. Asterisk (*) indicates significant difference from control (P < 0.05); a indicates significant difference from zebularine or SAHA alone (P < 0.05); b indicates significant difference from zebularine or 5-azaDc alone (P < 0.05). “Zeb” indicates zebularine. D. MDA-MB-231 cells were plated in a 6-well plate and treated with zebularine or vorinostat or both for colony formation assay. Results from one of three colony formation assay experiments that gave similar results are shown

To determine whether treatment with zebularine and vorinostat can inhibit clonogenicity, MDA-MB-231 cells were plated as single cells with either 50 μM zebularine or 2.5 μM vorinostat or both. Although clonogenic potential was reduced by zebularine or vorinostat, colonies were absent upon combination treatment (Fig. 6b).

Discussion

Epigenetic modifications in cancer are reversible events and hence drugs targeting these mechanisms like HDAC and DNMT inhibitors are under evaluation for major cancers including breast cancer. Two DNMT inhibitors, azaC and 5-azaDc, have been shown to be effective in the clinic; their use is limited by toxicity, stability, efficacy, and need for intravenous administration. Hence, there is considerable interest in developing novel DNMT inhibitors that would be more effective and stable and less toxic. Studies in several cancer cell models have supported the use of the DNMT and cytidine deaminase inhibitor, zebularine, as a potent antitumor therapeutic because of its stability [28], minimal toxicity [18], and oral bioavailability [15]. In particular it has been found to be very stable with a half-life of 44 h at pH 1.0 and over 500 h at pH 7.0 [29]. For these reasons we assessed the effects of zebularine in human breast cancer cell lines of clinically relevant phenotypes. Our study shows that zebularine induces an S-phase arrest through alteration in expression of cell cycle regulatory proteins and induces changes in protein expression consistent with apoptosis in two human breast cancer cell lines. Alterations of expression of multiple epigenetic regulatory proteins were also observed, generally at 50–100 μM, and expression of a candidate epigenetically regulated gene, ER, was also enhanced at this lower dose. This difference in dose response suggests that the epigenetic regulatory properties of zebularine can be separated from its apoptosis inducing properties, an important finding to support combination studies. As predicted, low doses of zebularine in combination with DNMT or HDAC inhibitors inhibit cell proliferation and colony formation in MDA-MB-231 cells more than either agent alone.

The effect of zebularine on cell proliferation was assayed by MTT. Although minimal effects were seen after 24 h of zebularine exposure, a significant dose and time dependent inhibition of cell proliferation was observed thereafter. The IC50s of zebularine were 150, 99 and 88 μM in MDA-MB-231 and 426, 180 and 149 μM in MCF-7 cells on exposure for 48, 72 and 96 h, respectively. In comparison with MDA-MB-231 cells, MCF-7 cells were less susceptible to zebularine mediated toxicity for uncertain reasons, perhaps related to their lower growth rate. In contrast to other DNMT inhibitors, zebularine is relatively less-toxic to breast cancer cell lines, and these findings are consistent with reports of its effects in other cancer cell lines. For example the IC50s of zebularine in ovarian cancer cells treated for 48 h were 152, 91 and 65 μM in A2780/CP, A2780, and Hey cell lines, respectively, while the IC50 was 120 μM in T24 bladder cancer cells [30]. Treatment of AML-193 myeloid leukemia cells with 250 or 500 μM zebularine led to an approximate 85% inhibition in cell proliferation [16]. Our study confirms that, like in other cell lines, zebularine is minimally toxic to both ER negative and ER positive cell lines at low doses and shorter exposure times.

Because of these growth differences, we further explored the mechanism of action of zebularine in ER-negative and ER-positive breast cancer cell lines. Zebularine induces apoptosis by differential activation of apoptosis signaling cascades in ER positive and ER negative cell lines as previously observed with other agents like sulforaphane [31]. In MDA-MB-231 cells, apoptosis appears to be triggered by both extrinsic and intrinsic pathways through inhibition of antiapoptotic Bcl2 and activation of Bax and caspase-3, leading to cleavage of PARP in a pathway similar to 5-azaDc [32]. The Bax/Bcl2 ratio is increased at all zebularine doses tested, shifting the cells toward apoptosis. These results are consistent with previous reports in pancreatic cancer cell lines. Zebularine treatment of YAP C (10 mM), DAN G (1 mM), and Panc-89 (1 mM) cells for 48 or 96 h induced apoptosis characterized by downregulation of Bcl2 and increased or stable expression of Bax, resulting in an altered Bax/Bcl2 ratio indicating apoptosis. In vivo, upregulation of Bax was reported in Panc-89 xenograft mice treated with 1 g/kg zebularine where zebularine treatment led to a time and dose dependent increase in apoptosis in association with enhanced expression of Bax and cytokeratin-7 and down regulation of Bcl2 [33]. However, in MCF-7 cells, our finding that Bcl2 is decreased in the absence of caspase 3 suggests that apoptosis is mediated through a pathway different from MDA-MB-231 cells.

Zebularine treatment led to increased p21 protein expression coupled with decreased cyclin B and D protein expression in MCF-7 cells, consistent with the flow cytometric analysis showing an increased percentage of cells in S-phase that indicates a zebularine induced S-phase arrest. This finding suggests errors in chromatin assembly that contribute to genome instability [34]. S-phase arrest can also be triggered by repression of histone synthesis in human cells [35]. It is reported that DNMT1 knock down triggers an intra-S-phase arrest, which is believed to be due to reduction in DNMT1 protein rather than demethylation events [36]. Hence, we believe that the genomic instability induced by DNMT1 down regulation and repression of histone synthesis triggers the activation of S-phase check point proteins like p21 (in MCF-7 cells) and/or down regulates cyclin-D to permit DNA repair before entering G2 phase. The zebularine-mediated decrease in expression of global acetylated histones observed in our studies further supports our hypothesis. In contrast, zebularine did not alter cell cycle in acute myeloid leukemic Kasumi-1 cell lines [37]. However, the highest dose used in that study was 50 μM, while S-phase arrest was evident only at 200 μM in breast cancer cells.

Zebularine is a cytidine deaminase and DNMT inhibitor and its ability to induce epigenetic alterations has already been reported [15, 18]. Here zebularine depleted expression of all three DNMT proteins post-transcriptionally in both breast cancer cell lines at most doses tested. It has been reported that human cancer cells lacking DNMT1 or DNMT3b retain significant global methylation and gene silencing, but those lacking both DNMT1 and DNMT3b had >95% reduction in genomic DNA methylation and virtually absent DNMT activity [38]. Our studies show that zebularine treatment specifically targets DNMT1, and results in partial reduction in DNMT 3a and 3b protein expression, implying that treated cells may still retain substantial methylation. Similar results were seen in T24 bladder cancer cells continuously treated with zebularine for 40 days. In these cells zebularine had no effect on the expression of DNMT1, 3a or 3b mRNA but complete loss of DNMT1 and partial depletion of DNMT 3a and 3b protein were observed [18].

The ability of zebularine to reactivate expression of epigenetically silenced genes has been evaluated in several model systems. It has been shown that exposure to zebularine reactivates silenced genes including p16 in bladder, colon and prostate cancer cells [15], E-cadherin in Akata cells [17] and p15INK4B in AML-193 cells [16]. However, p16 expression in zebularine-treated T-24 bladder cancer cells was 10–100-fold lower than that seen with 5-azaDC [13]. That there is some specificity for genes that are reactivated is suggested by the finding that zebularine reactivates silenced E-cadherin without switching from latent to lytic Epstein-Barr virus infection in Burkitt's lymphoma Akata cells [17]. In addition, the mechanism may not be solely one of demethylation; indeed it was felt that zebularine reactivates silenced genes like P15INK4B in AML-193 cells through regional enrichment of histone acetylation at its promoter [16].

Because of our previous findings that ER can be epigenetically silenced in some human breast cancer cell lines and HDAC or DNMT inhibitors could reexpress functional ER in ER negative breast cancer cells [24, 25, 39], we explored if zebularine treatment reactivates ER. Our study demonstrated that treatment of ER negative MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells with zebularine results in functional ER reactivation as manifested by expression of ER mRNA and its target gene, PR. This was seen with a dose as low as 50 μM, far lower than doses that induced apoptosis. Chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis of the ER promoter in zebularine-treated cells showed characteristics of an active chromatin as manifested by accumulation of acetylated H3 and H4 and release of DNMT1, 3a and 3b from the ER promoter region. Although reexpression of ER with zebularine was not as robust as with 5-azaDc, the low toxicity could enable continuous administration for sustained reexpression of ER.

Some potential limitations for the use of zebularine as a therapeutic do exist. As with other DNMT inhibitors hypothetical concerns exist about specificity; this is a concern about most antineoplastics at present. In addition our studies and others [15] have shown that zebularine is less potent than the two FDA-approved DNMT inhibitors, azaC and 5-azaDc. Doses of 100–500 μM are required for substantial demethylation [17, 19]. It is hypothesized that the reduced inhibitor potency is due to sequestration of the drug by cytidine deaminase, competitive inhibition of zebularine incorporation into DNA by increased cytidine and deoxycytidine that accumulate as a consequence of its cytidine deaminase properties, and preferential incorporation of zebularine into RNA over DNA [30]. For these reasons, the drug is effective only at very high doses, making administration more problematic. However, it has been successfully administered in a long-term study demonstrating its effects as a chemopreventive in the MIN mouse model [40]. Its efficacy combined with a low toxicity profile makes it an attractive agent for combination or sequential therapy with other DNMT or HDAC inhibitors or other biologics.

Cytidine deaminase destabilizes DNMT inhibitors like 5-azaDc, resulting in complete loss of their antineoplastic ability [41]. Hence administration of cytidine deaminase inhibitors like zebularine should theoretically potentiate therapeutic effects of 5-azaDc by slowing its degradation and stabilizing activity. Indeed, the combination of 5-aza-Dc and zebularine produced greater inhibition in cell proliferation and clonogenicity than either drug alone in leukemic L1210 and HL-60 cell lines [42]. Similarly, treatment of the AML-193 acute myeloid leukemic cell line, which has a densely methylated p15INK4B CpG island, with zebularine followed by the HDAC inhibitor, trichostatin-A, synergistically enhanced p15INK4B expression [16]. Consistent with these results, the combination of 50 μM zebularine and 1 μM 5-azaDc in breast cancer cells significantly inhibited cell proliferation compared with either drug alone. Similarly, zebularine significantly inhibited cell proliferation and colony formation in combination with low doses of vorinostat. Our study forms a basis for novel therapeutic approaches in the treatment of breast cancer through a combination of zebularine and other epigenetic therapeutics.

In conclusion, our data demonstrate that zebularine is an effective demethylating agent, and reactivates a key gene normally silenced in some breast cancer cell lines even at low doses. Zebularine acts through post-transcriptional inhibition of DNMTs, inhibition of methyl CpG binding proteins and alteration of global histone acetylation status. The ability to administer zebularine with other epigenetic therapeutics with at least additive effect has also been established. These results provide a rationale to continue research with zebularine and its derivatives, and explore the development of novel DNMT inhibitors that can be used in combination for breast cancer treatment.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH CA 88843) and the Breast Cancer Research Foundation.

Contributor Information

Madhavi Billam, Email: madhumukhi@gmail.com, The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21231, USA.

Michele D. Sobolewski, Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, NY 14263, USA

Nancy E. Davidson, Email: davidsonne@upmc.edu, University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute, 5150 Centre Avenue, Suite 500, Pittsburgh, PA 15232, USA.

References

- 1.Wood LD, Parsons DW, Jones S, et al. The genomic landscapes of human breast and colorectal cancers. Science. 2007;318:1108–1113. doi: 10.1126/science.1145720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baylin SB, Ohm JE. Epigenetic gene silencing in cancer—a mechanism for early oncogenic pathway addiction? Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:107–116. doi: 10.1038/nrc1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones PA, Baylin SB. The epigenomics of cancer. Cell. 2007;128:683–692. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Momparler RL, Vesely J, Momparler LF, Rivard GE. Synergistic action of 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine and 3-deazauridine on L1210 leukemic cells and EMT6 tumor cells. Cancer Res. 1979;39:3822–3827. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santi DV, Norment A, Garrett CE. Covalent bond formation between a DNA-cytosine methyltransferase and DNA containing 5-azacytosine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:6993–6997. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.22.6993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Constantinides PG, Taylor SM, Jones PA. Phenotypic conversion of cultured mouse embryo cells by aza pyrimidine nucleosides. Dev Biol. 1978;66:57–71. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(78)90273-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gabbara S, Bhagwat AS. The mechanism of inhibition of DNA (cytosine-5-)-methyltransferases by 5-azacytosine is likely to involve methyl transfer to the inhibitor. Biochem J. 1995;307:87–92. doi: 10.1042/bj3070087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beisler JA. Isolation, characterization, and properties of a labile hydrolysis product of the antitumor nucleoside, 5-azacytidine. J Med Chem. 1978;21:204–208. doi: 10.1021/jm00200a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Constantinides PG, Jones PA, Gevers W. Functional striated muscle cells from non-myoblast precursors following 5-azacytidine treatment. Nature. 1977;267:364–366. doi: 10.1038/267364a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marquez VE, Liu PS, Kelley JA, Driscoll JS, McCormack JJ. Synthesis of 1, 3-diazepin-2-one nucleosides as transition-state inhibitors of cytidine deaminase. J Med Chem. 1980;23:713–715. doi: 10.1021/jm00181a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim CH, Marquez VE, Mao DT, Haines DR, McCormack JJ. Synthesis of pyrimidin-2-one nucleosides as acid-stable inhibitors of cytidine deaminase. J Med Chem. 1986;29:1374–1380. doi: 10.1021/jm00158a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laliberte J, Marquez VE, Momparler RL. Potent inhibitors for the deamination of cytosine arabinoside and 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine by human cytidine deaminase. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1992;30:7–11. doi: 10.1007/BF00686478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marquez VE, Barchi JJ, Jr, Kelley JA, et al. Zebularine: a unique molecule for an epigenetically based strategy in cancer chemotherapy. The magic of its chemistry and biology. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2005;24:305–318. doi: 10.1081/NCN-200059765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hurd PJ, Whitmarsh AJ, Baldwin GS, et al. Mechanism-based inhibition of C5-cytosine DNA methyltransferases by 2-H pyrimidinone. J Mol Biol. 1999;286:389–401. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng JC, Matsen CB, Gonzales FA, et al. Inhibition of DNA methylation and reactivation of silenced genes by zebularine. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:399–409. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.5.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scott SA, Lakshimikuttysamma A, Sheridan DP, Sanche SE, Geyer CR, DeCoteau JF. Zebularine inhibits human acute myeloid leukemia cell growth in vitro in association with p15INK4B demethylation and reexpression. Exp Hematol. 2007;35:263–273. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rao SP, Rechsteiner MP, Berger C, Sigrist JA, Nadal D, Bernasconi M. Zebularine reactivates silenced E-cadherin but unlike 5-Azacytidine does not induce switching from latent to lytic Epstein-Barr virus infection in Burkitt's lymphoma Akata cells. Mol Cancer. 2007;6:6. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-6-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng JC, Weisenberger DJ, Gonzales FA, et al. Continuous zebularine treatment effectively sustains demethylation in human bladder cancer cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:1270–1278. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.3.1270-1278.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng JC, Yoo CB, Weisenberger DJ, et al. Preferential response of cancer cells to zebularine. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agoston AT, Argani P, Yegnasubramanian S, et al. Increased protein stability causes DNA methyltransferase 1 dysregulation in breast cancer. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:18302–18310. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501675200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hahm HA, Dunn VR, Butash KA, et al. Combination of standard cytotoxic agents with polyamine analogues in the treatment of breast cancer cell lines. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:391–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Franken NA, Rodermond HM, Stap J, Haveman J, van Bree C. Clonogenic assay of cells in vitro. Nat Protocols. 2006;1:2315–2319. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keen JC, Yan L, Mack KM, et al. A novel histone deacetylase inhibitor, scriptaid, enhances expression of functional estrogen receptor alpha (ER) in ER negative human breast cancer cells in combination with 5-aza 2′-deoxycytidine. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003;81:177–186. doi: 10.1023/A:1026146524737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferguson AT, Lapidus RG, Baylin SB, Davidson NE. Demethylation of the estrogen receptor gene in estrogen receptor negative breast cancer cells can reactivate estrogen receptor gene expression. Cancer Res. 1995;55:2279–2283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharma D, Blum J, Yang X, Beaulieu N, Macleod AR, Davidson NE. Release of methyl CpG binding proteins and histone deacetylase 1 from the Estrogen receptor alpha (ER) promoter upon reactivation in ER-negative human breast cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:1740–1751. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Margueron R, Licznar A, Lazennec G, Vignon F, Cavailles V. Oestrogen receptor alpha increases p21(WAF1/CIP1) gene expression and the antiproliferative activity of histone deacetylase inhibitors in human breast cancer cells. J Endocrinol. 2003;179:41–53. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1790041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sheikh MS, Shao ZM, Chen JC, Li XS, Hussain A, Fontana JA. Expression of estrogen receptors in estrogen receptor negative human breast carcinoma cells: modulation of epidermal growth factor-receptor (EGF-R) and transforming growth factor alpha (TGF alpha) gene expression. J Cell Biochem. 1994;54:289–298. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240540305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barchi JJ, Musser S, Marquez VE. The decomposition of 1-(beta-D-ribofuranosyl)-1, 2-dihydropyrimidin-2-one (zebularine) in alkali—mechanism and products. J Org Chem. 1992;57:536–541. doi: 10.1021/jo00028a026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoo CB, Cheng JC, Jones PA. Zebularine: a new drug for epigenetic therapy. Biochem Soc Trans. 2004;32:910–912. doi: 10.1042/BST0320910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ben-Kasus T, Ben-Zvi Z, Marquez VE, Kelley JA, Agbaria R. Metabolic activation of zebularine, a novel DNA methylation inhibitor, in human bladder carcinoma cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;70:121–133. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pledgie-Tracy A, Sobolewski MD, Davidson NE. Sulforaphane induces cell type-specific apoptosis in human breast cancer cell lines. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:1013–1021. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tamm I, Wagner M, Schmelz K. Decitabine activates specific caspases downstream of p73 in myeloid leukemia. Ann Hematol. 2005;84:47–53. doi: 10.1007/s00277-005-0013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neureiter D, Zopf S, Leu T, et al. Apoptosis, proliferation and differentiation patterns are influenced by zebularine and SAHA in pancreatic cancer models. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:103–116. doi: 10.1080/00365520600874198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ye X, Franco AA, Santos H, Nelson DM, Kaufman PD, Adams PD. Defective S phase chromatin assembly causes DNA damage, activation of the S phase checkpoint, and S phase arrest. Mol Cell. 2003;11:341–351. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nelson DM, Ye X, Hall C, et al. Coupling of DNA synthesis and histone synthesis in S phase independent of cyclin/cdk2 activity. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:7459–7472. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.21.7459-7472.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Milutinovic S, Zhuang Q, Niveleau A, Szyf M. Epigenomic stress response. Knockdown of DNA methyltransferase 1 triggers an intra-S-phase arrest of DNA replication and induction of stress response genes. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:14985–14995. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M213219200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Flotho C, Claus R, Batz C, et al. The DNA methyltransferase inhibitors azacitidine, decitabine and zebularine exert differential effects on cancer gene expression in acute myeloid leukemia cells. Leukemia. 2009 doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rhee I, Bachman KE, Park BH, et al. DNMT1 and DNMT3b cooperate to silence genes in human cancer cells. Nature. 2002;416:552–556. doi: 10.1038/416552a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang X, Ferguson AT, Nass SJ, et al. Transcriptional activation of estrogen receptor alpha in human breast cancer cells by histone deacetylase inhibition. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6890–6894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoo CB, Chuang JC, Byun HM, et al. Long-term epigenetic therapy with oral zebularine has minimal side effects and pre vents intestinal tumors in mice. Cancer Prev Res. 2008;1:233–240. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-07-0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eliopoulos N, Cournoyer D, Momparler RL. Drug resistance to 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine, 2′, 2′-difluorodeoxycytidine, and cytosine arabinoside conferred by retroviral-mediated transfer of human cytidine deaminase cDNA into murine cells. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1998;42:373–378. doi: 10.1007/s002800050832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lemaire M, Momparler LF, Bernstein ML, Marquez VE, Momparler RL. Enhancement of antineoplastic action of 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine by zebularine on L1210 leukemia. Anticancer Drugs. 2005;16:301–308. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200503000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]