Abstract

Objective

Most studies have assessed conflict between clinicians and surrogate decision makers in ICUs from only clinicians’ perspectives. It is unknown if surrogates’ perceptions differ from clinicians’. We sought to determine the degree of agreement between physicians and surrogates about conflict, and to identify predictors of physician-surrogate conflict.

Design

Prospective cohort study.

Setting

Four ICUs of two hospitals in San Francisco, California.

Patients

230 surrogate decision makers and 100 physicians of 175 critically ill patients.

Measurements

Questionnaires addressing participants’ perceptions of whether there was physician-surrogate conflict, as well as attitudes and preferences about clinician-surrogate communication; kappa scores to quantify physician-surrogate concordance about the presence of conflict; and hierarchical multivariate modeling to determine predictors of conflict.

Main Results

Either the physician or surrogate identified conflict in 63% of cases. Physicians were less likely to perceive conflict than surrogates (27.8% vs 42.3%; p=0.007). Agreement between physicians and surrogates about conflict was poor (kappa = 0.14). Multivariable analysis with surrogate-assessed conflict as the outcome revealed that higher levels of surrogates’ satisfaction with physicians’ bedside manner were associated with lower odds of conflict (OR: 0.75 per 1 point increase in satisfaction, 95% CI 0.59–0.96). Multivariable analysis with physician-assessed conflict as the outcome revealed that the surrogate having felt discriminated against in the healthcare setting was associated with higher odds of conflict (OR 17.5, 95% CI 1.6–190.1) while surrogates’ satisfaction with physicians’ bedside manner was associated with lower odds of conflict (0–10 scale, OR 0.76 per 1 point increase, 95% CI 0.58–0.99).

Conclusions

Conflict between physicians and surrogates is common in ICUs. There is little agreement between physicians and surrogates about whether physician-surrogate conflict has occurred. Further work is needed to develop reliable and valid methods to assess conflict. In the interim, future studies should assess conflict from the perspective of both clinicians and surrogates.

Keywords: conflict, surrogate decision making

Introduction

Research in the last decade has revealed that clinician-surrogate conflict is prevalent in intensive care units (ICUs)[1–5]. In a multi-center study in Europe[2], 27% of clinicians reported at least one conflict between ICU staff and patients or families in the preceding week. Clinicians caring for patients with a prolonged stay in the ICU identified conflict between the medical team and the family in 22% of cases[5]. A single center study of cases in which limitation of life-sustaining therapy was discussed found that clinicians identified conflict with surrogates in 48% of cases[3], while surrogates identified conflict with clinicians in 40% of cases[1], but clinician-surrogate agreement was not assessed. Conflict is a significant problem because there is mounting evidence that it associated with adverse outcomes for both clinicians and families. Clinicians in ICUs report that conflict contributes to burnout[6, 7] and may contribute to loss of workforce in the field. Research outside of medical settings indicates conflict causes emotional distress[8], anxiety, and stress[9], as well as mistrust and misunderstandings of the other party’s behavior[10, 11]. However, conflict that is appropriately identified and managed can have positive effects, including helping family members move through emotionally challenging circumstances[12–14].

Although several studies have identified a high prevalence of conflict in ICUs, most have assessed only clinicians’ perspectives, and no studies have assessed the perspectives of physicians and surrogates simultaneously and prospectively. This may lead to an incomplete view of conflict if surrogates perceive conflict differently from clinicians. This is important because it remains unknown whether clinicians and surrogates agree about the occurrence of conflict, and thus whether clinicians’ perspectives can serve as a valid proxy for surrogates’ perceptions of conflict.

We therefore investigated: 1) the prevalence of surrogate- and physician-identified conflict, and the degree of agreement between these groups regarding the presence of conflict; and 2) factors associated with physician-surrogate conflict.

Materials and Methods

From January 2006 to October 2007, we conducted a prospective cohort study of surrogate decision makers and primary ICU physicians (attending intensivists and fellows in training) of critically ill patients in four ICUs at the University of California, San Francisco Medical Center. Study methods have been previously described[15]. We identified eligible patients and their surrogates by daily screening in each ICU. Eligible patients were incapacitated, with respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation and an Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score greater than 25. We enrolled the surrogate decision makers and physicians of these patients. Patients dying within 48 hours of initiating mechanical ventilation and their surrogates were not eligible, per Institutional Review Board (IRB) requirements. If two or more family members identified themselves as participating in decision making for the patient, more than one surrogate per patient could be enrolled. Additional inclusion requirements for surrogates included age at least 18 years old and the ability speak and read English well enough not to require an interpreter. The IRB of the University of California, San Francisco approved all study procedures, and all subjects gave informed consent to participate; no study procedures occurred at the investigators’ present institution, so IRB approval was not required.

In order to achieve 80% power to detect an absolute 10% difference in prevalence of conflict (based upon a 2-sample test of proportions) at a 5% α-level, 142 patients were required.

Data Collection

We abstracted demographic and clinical information pertaining to patients from medical charts. On patients’ 5th day of mechanical ventilation, participating surrogates and physicians completed a written, self-administered questionnaire eliciting demographic information as well as attitudes and beliefs about physicians’ and surrogates’ roles, communication practices and preferences, and prior experiences.

Outcome Measures

We assessed our main outcome with a one-item conflict question on a zero to ten scale, developed by Abernethy and Tulsky[16]. Participants were asked, “How much disagreement, including conflicts and negative feelings, has there been between you and (this doctor/this family) regarding (your loved one’s/this patient’s) care?” This instrument was originally tested for acceptability and reliability with ICU clinicians[16], and subsequently adapted for use in a qualitative study of physicians and surrogates[1, 3].

Surrogates provided information regarding prior experiences as a surrogate decision maker and whether the surrogate had discussed treatment preferences with the patient. We evaluated surrogates’ satisfaction with physicians’ bedside manner during the conference with the question, “How satisfied are you with the doctor’s bedside manner when he/she discussed your loved one’s prognosis?” on a 0 to 10 scale. We also assessed surrogates’ perceptions of the quality of their communication with the physician using the validated 17-item Quality of Communication instrument, which measures several dimensions of communication (listening, attending to emotion, communicating prognosis, using appropriate terminology, addressing spiritual or religious beliefs, and overall assessment of communication)[17]. We assessed trust in the patient’s attending physician with the 5-item Physician Trust instrument[18]. Physicians provided information about their subspecialty training and time in practice, as well as their self-assessed skill in delivering prognostic information. All subjects answered questions regarding the influence of religion in their daily life and decision making. Participants also completed a validated measure of their view of patients’ and doctors’ roles (Patient Provider Orientation Scale)[19]. This instrument provides a mean score ranging from 1 to 6, with higher scores reflecting a preference toward a more patient-centered approach to healthcare and lower scores indicating preference toward a more biomedical model.

Statistical Analysis

Using the conflict scale described above, we first analyzed participants’ reported level of conflict descriptively. We next dichotomized subject responses to “no conflict” (response=0) or “any conflict” (response>0) to determine the incidence of any conflict. Next, to evaluate whether physician surrogate concordance about prognosis varied according to the intensity of the conflict, we dichotomized responses to conflict <5 (low conflict) and conflict ≥5 (high conflict). In cases in which more than one surrogate per patient enrolled, we conducted a per patient analysis in which we considered any surrogate’s rating of conflict to qualify as conflict for that family. The rationale for this strategy is that it is likely important for physicians to perceive conflict regardless of whether it occurs with one or several individuals acting as surrogates for a patient.

To evaluate whether there is a difference between physicians’ and surrogates’ perceptions of conflict, we performed a χ2 calculation or McNemar’s test comparing the prevalence of physician-assessed conflict with the prevalence of surrogate-assessed conflict. We performed a kappa calculation to assess physician-surrogate agreement about the presence of conflict within cases.

To identify factors associated with conflict, we used a hierarchical logistic regression model, which accounts for two forms of clustering: cases in which more than family member was involved in surrogate decision making, and physicians who cared for more than one enrolled patient. We created separate models using surrogate-identified conflict and physician-identified conflict as outcomes. In order to capture situations in which one party perceives some conflict and the other perceives none, we constructed all logistic models using conflict dichotomized to 0 (no conflict) and >0 (any conflict). When using surrogate-identified conflict as the outcome of interest, regression was performed accounting for nesting within patients, nesting within physicians; and when physician-identified conflict was used as the outcome measure, nesting within patients only was accounted for in the regression. We first created models with individual covariates to identify variables of interest. Variables with a p<0.20 in unadjusted modeling were included in multivariable models, as well as select variables with p values less than 0.25 and low collinearity with other variables. We selected final variables based on significance levels of p≤0.05 in multivariable regression models.

Results

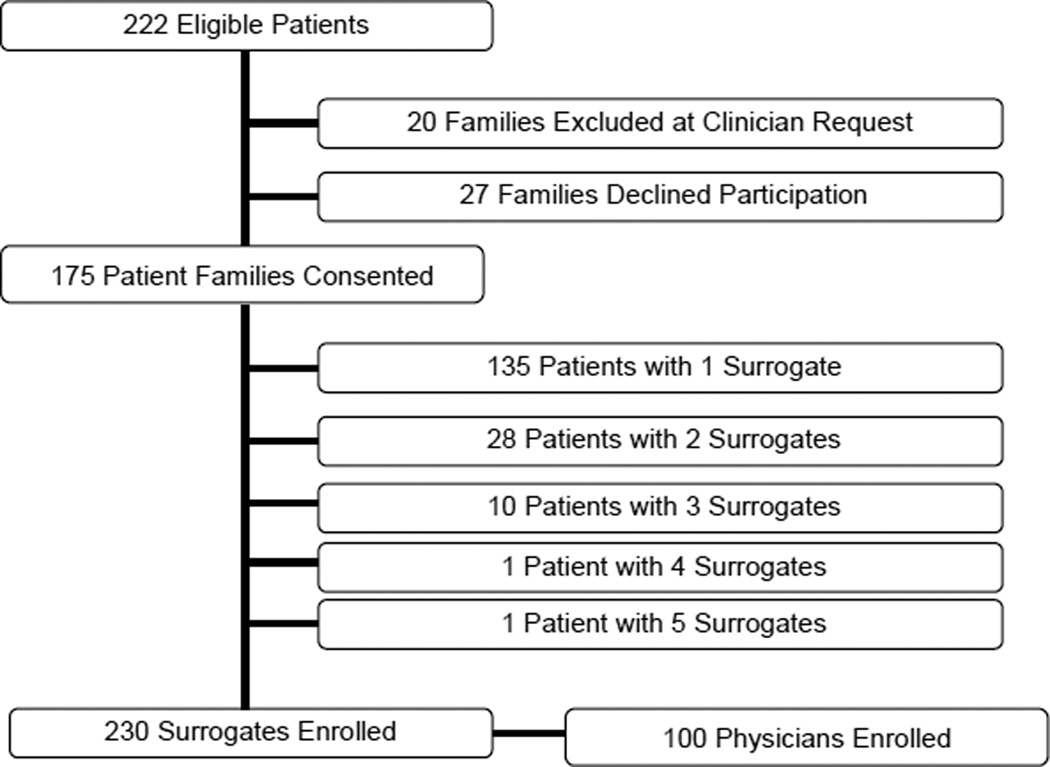

Of 222 eligible patients, 20 were excluded at the attending physician’s request. These cases generally comprised cases in which the family was so overwhelmed and grief-stricken that the physician was concerned that approaching them to participate in a research study may cause harm, and cases in which the family had threatened legal action. 27 of the patients’ surrogates declined to participate. For the remaining 175 patients (enrollment rate 79%), we enrolled 230 surrogate decision makers and 100 physicians; 40 patients had more than one surrogate enrolled (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram describing enrollment.

Table 1 summarizes patient, surrogate, and physician demographic characteristics and covariates.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of patients, surrogates, and physicians

| Characteristics of Patients | N= 175 |

|---|---|

| n (%) | |

| Gender | |

| Male | 98 (56) |

| Race | |

| White | 102 (63) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 33 (20.5) |

| Black/African-American | 17 (10.5) |

| Other/Not reported | 10 (6) |

| Life-sustaining therapy withdrawn | 67 (38) |

| Died | 75 (43) |

| Admission diagnosis | |

| Respiratory failure | 48 (27.5) |

| Neurologic failure | 46 (26) |

| Cardiac failure or shock (incl sepsis) | 44 (24) |

| Gastrointestinal failure (incl pancreatitis) | 14 (8) |

| Hepatic failure | 13 (7.5) |

| Metastatic cancer | 7 (4) |

| Renal failure | 3 (2) |

| Mean (SD) | |

| Age (years) | 59 (18.2) |

| APACHEII score on enrollment | 29 (4.6) |

| Characteristics of Surrogates | N= 230 |

|---|---|

| n (%) | |

| Gender | |

| Male | 74 (32.2) |

| Race | |

| White | 138 (64.8) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 34 (16.0) |

| Black/African-American | 23 (10.8) |

| Other/Not reported | 18 (8.4) |

| Hispanic | |

| No | 195 (85.5) |

| Relationship to Patient | |

| Spouse | 56 (24.4) |

| Child | 86 (37.4) |

| Sibling | 24 (10.4) |

| Friend | 4 (1.7) |

| Parent | 25 (10.9) |

| Other relative | 18 (7.8) |

| Other relationship | 17 (7.4) |

| Felt discriminated against in health setting, last 12 mos | 11 (4.8) |

| Past surrogate experience | 119 (52) |

| Mean (SD) | |

| Age (years) | 46.5 (14.6) |

| Characteristics of Physicians | N=100 |

|---|---|

| n (%) | |

| Gender | |

| Male | 64 (64) |

| Race | |

| White | 65 (65) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 25 (25) |

| Black/African-American | 1 (1) |

| Other/Not reported | 6 (6) |

| Hispanic | |

| No | 96 (96) |

| Attending physician | 97 (97) |

| Medical Specialtya | |

| Internal Medicine (or subspecialty) | 56 (56) |

| Neurology | 17 (17) |

| Surgery (or subspecialty) | 23 (23) |

| Anesthesia | 5 (5) |

| Mean (SD) | |

| Age (years) | 42 (9.3) |

| Years in Practice | 11 (9.6) |

Sums are greater than n=100 Physicians because some individuals identified more than one medical specialty

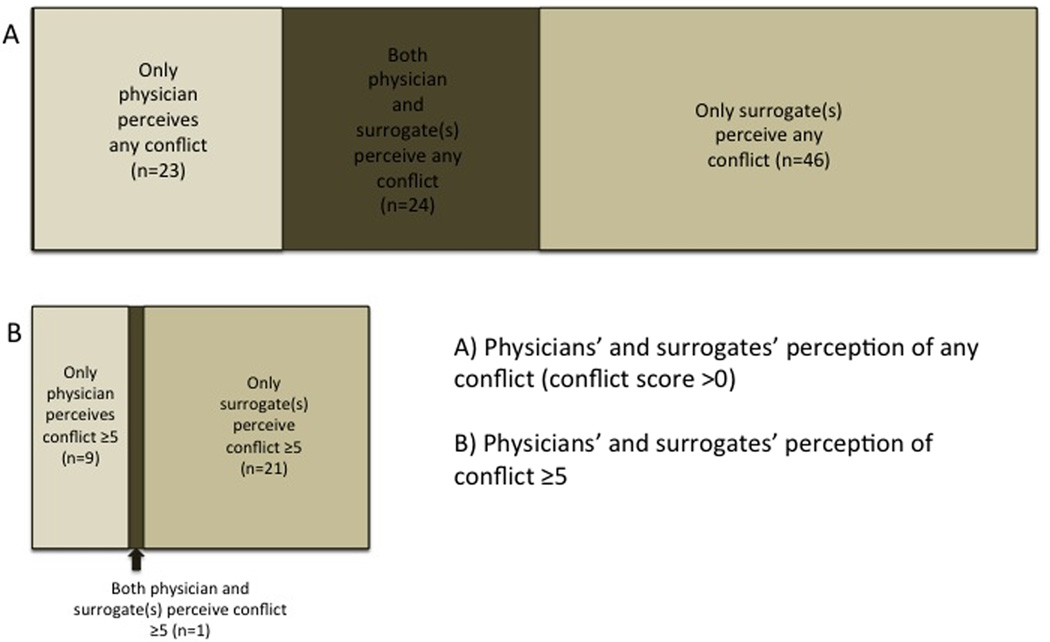

Surrogates perceived a mean level of conflict of 1.2 on a 0–10 scale (SD 2.32, range 0–10), and physicians perceived a mean level of conflict of 0.8 (SD 1.71, range 0–10), with both distributions rightward-skewed (see figure 3, online supplement). Either the physician or a surrogate identified any conflict in 63% of cases (110/175 cases), and both physician and surrogate identified conflict in 13% of cases (23/175 cases). Physicians perceived any conflict less frequently than surrogates (27.8% v 42.3%, p=0.007). Surrogates perceived any conflict in 51% of cases in which physicians identified any conflict, while physicians perceived any conflict in 34% of cases in which surrogates identified any conflict. Agreement between physicians and surrogates about the occurrence of any conflict was poor, κ=0.14. Figure 2 illustrates the physician and surrogate concordance about the occurrence of conflict.

Figure 2.

Physicians’ and surrogates’ agreement about conflict

Either the physician or surrogate perceived conflict rated at 5 or greater in 18% of cases (31/175 cases), and both the physician and surrogate identified conflict ≥5 in 0.6% of cases (1/175 cases). At least one surrogate perceived conflict ≥5 in 13% of cases (22/175 cases), while physicians perceived conflict ≥5 in 6% of cases (10/175 cases; p=0.03). In the 22 cases in which surrogates perceived conflict ≥5, only one physician also perceived conflict ≥5 (4.6%), and only 10 (45.5%) physicians perceived any conflict (>0). Physician-surrogate agreement using conflict of 5 or greater as the cut-point was no better than would be expected by chance, κ=−0.02. (Figure 2)

Table 2 summarizes the results of the unadjusted analysis with surrogates’ identification of any conflict as the outcome measure. Multivariable analysis revealed significant negative association of conflict with surrogate’s satisfaction with physician bedside manner, with an adjusted OR of 0.75 per 1 point increase in satisfaction on a 10-point scale (95% CI 0.59–0.96). (Table 3)

Table 2.

Univariate analysis – Surrogate identification of conflict as outcome

| Independent Variable | OR [95% Confidence Interval] |

P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Surrogate-level variables | ||

| Influence of religion in decision making | 0.907[0.67–1.23] | 0.5281 |

| Surrogate relation to patient (versus other non-relative): | ||

| Spouse | 1.203[0.31–4.633] | 0.7856 |

| Child | 2.420[0.68–8.656] | 0.1711 |

| Sibling | 3.814[0.87–16.796] | 0.0760 |

| Friend | 3.674[0.32–41.705] | 0.2889 |

| Parent | 2.141[0.49–9.419] | 0.3087 |

| Other Relative | 0.984[0.18–5.253] | 0.9843 |

| Previously discussed patient’s preferences for LST | 0.727[0.41–1.30] | 0.2788 |

| Understanding of patient’s preferences for LST (0–10 scale, by 1 point) | 0.874[0.77–0.99] | 0.0331 |

| Previously served as surrogate decision maker | 1.684[0.94–3.02] | 0.0792 |

| Felt discriminated against in health care setting in last 12 mos | 3.436[0.91–13.04] | 0.0694 |

| Belief in MD’s prognosis for patient (0–10 scale, by 1 point) | 0.776[0.66–0.92] | 0.0038 |

| Satisfaction with MD’s bedside manner (0–10 scale, by 1 point) | 0.692[0.56–0.86] | 0.0011 |

| Increasing PPO score (1–6 scale, by 1 point, increasing score=more patient centered) | 1.034[0.76–1.40] | 0.8277 |

| Physician-level variables | ||

| Attending physician vs other MD | 0.849[0.113–6.367] | 0.8724 |

| Physician specialty | * | |

| Influence of religion in decision making (1–4 scale, by 1 point) | 0.921[0.661–1.283] | 0.6228 |

| Years in practice post residency, by 1 year | 1.003[ 0.971–1.036] | 0.8645 |

| Self-assessed skill in discussing prognosis (0–10 scale, by 1 point) | 0.903[0.706–1.156] | 0.4139 |

| Preferred level of control in EOL decision making (1–5, by 1 point) | 0.987 [0.637–1.530] | 0.9541 |

| Preferred level of control in basic medical decision making (1–5, by 1 point) | 0.913 [0.513–1.627] | 0.7561 |

| Increasing PPO score (1–6 scale, by 1 point) | 0.942[0.569–1.561] | 0.8153 |

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis

| Independent Variable | OR [95% Confidence Interval] |

P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Surrogate-assessed conflict as outcome | ||

| Child vs any other relationship | 1.658[0.733–3.752] | 0.2214 |

| Sibling vs any other relationship | 2.489[0.715–8.670] | 0.1496 |

| Previously discussed patient’s preferences for LST | 0.769[0.333–1.775] | 0.5331 |

| Understanding of patient’s preferences for LST (0–10 scale, by 1 point) | 0.902[0.758–1.073] | 0.2401 |

| Previously served as surrogate decision maker | 1.961[0.890–4.319] | 0.0935 |

| Felt discriminated against in health care setting in last 12 mos | 4.094[0.499–33.575] | 0.1861 |

| Belief in MD’s prognosis for patient (0–10 scale, by 1 point) | 0.839[0.691–1.019] | 0.0761 |

| Satisfaction with MD’s bedside manner (0–10 scale, by 1 point) | 0.748[0.587–1.952] | 0.0192 |

| MD’s self-assessed skill in discussing prognosis (0–10 scale, by 1 point) | 1.105[0.800–1.526] | 0.5404 |

| Physician-assessed conflict as outcome | ||

| Child vs any other relationship | 0.941[0.385–2.298] | 0.8935 |

| Sibling vs any other relationship | 2.287[0.589–8.889] | 0.2299 |

| Previously discussed patient’s preferences for LST | 0.885[0.334–2.342] | 0.8035 |

| Understanding of patient’s preferences for LST (0–10 scale, by 1 point) | 1.006[0.817–1.240] | 0.9542 |

| Previously served as surrogate decision maker | 0.930[0.394–2.194] | 0.8675 |

| Felt discriminated against in health care setting in last 12 mos | 17.489[1.609–190.119] | 0.0192 |

| Belief in MD’s prognosis for patient (0–10 scale, by 1 point) | 1.092[0.874–1.365] | 0.4352 |

| Satisfaction with MD’s bedside manner (0–10 scale, by 1 point) | 0.768[0.594–0.994] | 0.0450 |

| MD’s self-assessed skill in discussing prognosis (0–10 scale, by 1 point) | 0.806[0.575–1.128] | 0.2058 |

Multivariable analysis with physicians’ identification of any conflict as the outcome revealed that a surrogate having felt discriminated against in a healthcare setting in the prior 12 months was significantly associated with higher odds of conflict, with an OR of 17.5 (95% CI 1.61–190.12), and surrogate’s satisfaction with the physician’s bedside manner was associated with lower odds of conflict, OR 0.77 per 1 point increase in satisfaction (95% CI 0.58–0.99) (Table 3). Table 4 (online supplement) summarizes unadjusted analysis with physicians’ identification of conflict as the outcome measure.

As a sensitivity analysis, we conducted unadjusted and multivariable modeling using combined surrogate- and physician-perceived conflict as the outcome. This analysis confirmed the associated factors identified in the main analysis except surrogate discrimination was no longer significantly associated with any conflict. This analysis also identified the death of the patient as significantly associated with combined physician-surrogate identification of conflict (see online supplement for tables 5 and 6 summarizing sensitivity analysis). There was no significant association with the patient-level variables tested in the main analysis (data not shown).

Discussion

We found that physicians or surrogates perceive conflict in nearly two-thirds of cases. Agreement was poor between physician and surrogates about whether conflict occurred.

The observed prevalence of conflict from the physicians’ perspectives is consistent with the prevalence observed in prior studies[2, 4, 5, 20]. In the Conflicus study, ICU clinicians reported extensively on conflicts they had experienced in the previous week[2], with 27% of the participants identifying a clinician-family conflict. Tulsky and colleagues retrospectively measured the perceptions of clinicians[3] of patients in whom limitation of life-sustaining therapy was discussed. They identified clinician-surrogate conflict in 48% of cases. Differences in prevalence estimates may be due to differences in the populations studied or differences in the timing of screening for conflict.

We found poor agreement between physicians and surrogates regarding the presence of conflict. These findings have implications for both clinical practice and research methodology. From a research methods standpoint, our findings suggest that physicians’ perceptions of conflict should not be used as a proxy for surrogates’ perceptions. There is also a need for further methodological work to develop reliable measures of conflict in healthcare. At a minimum, investigators seeking to measure conflict in ICUs should assess conflict from the perspectives of both physicians and surrogates in order to gain a more complete understanding. From the standpoint of clinical practice, physicians should be aware that they tend to underestimate the occurrence of conflict relative to surrogates’ perceptions, and should be alert to the possibility of unrecognized conflicts. Future research efforts are needed to better understand how physicians respond to conflict and what strategies are feasible and effective to diminish the adverse consequences of conflict on both physicians and surrogates.

We identified two factors that were associated with conflict. Higher levels of a surrogate’s satisfaction with the physician’s bedside manner were associated with lower odds of conflict from both the physician’s and surrogate’s perspective. There are at least three potential explanations for this finding. One explanation is that satisfaction with a physician’s bedside manner may be related to the proportion of time the physician spends listening as opposed to speaking during interactions with surrogates. An observational study found lower level of surrogates’ perception of conflict when families spent more time talking[21]. Another explanation is that this association may be similar to the well-described association of higher patient ratings of physician communication and lower incidence of malpractice lawsuits[22, 23]. Alternatively, the two measurements (conflict and satisfaction with bedside manner) may be testing similar constructs and our results may reflect this collinearity.

Our study has several strengths. To our knowledge, it is the first that measures physicians’ and surrogates’ perceptions of conflict prospectively and contemporaneously (within 3 hours of each other), which is challenging in light of the unpredictability of physicians’ and families’ schedules in ICUs. We were able to study a diverse population of surrogates, which lends generalizability to our results. We also achieved a high response rate, which minimizes the risk of response bias.

Our study also has several limitations. First, we measured conflict on patients’ 5th day of mechanical ventilation and therefore missed any conflicts that developed later in patients’ hospitalizations, early conflicts that may have been resolved prior to data collection, or conflicts occurring in ICU stays of less than 5 days. This may result in an underestimate of conflict relative to the true incidence. Nonetheless, we found that conflict was perceived in 63% of cases, which is a significant finding even if it underestimates the incidence of conflict. Second, we measured only physician-surrogate conflicts, and therefore may have missed important conflicts between surrogates and other clinicians, particularly bedside nurses, whose closer interactions with families may allow them access to conflicts that physicians do not perceive. We also did not study within-family conflict. Third, the cases excluded at the physicians’ request included cases in which the family had threatened legal action. This may also have led to an underestimate of the prevalence of conflict. Fourth, in some of the covariates tested in our regression modeling, sample sizes were so small as to likely prohibit definitive conclusions about their relationship to the outcome (e.g. the small number of fellows compared with attending physicians). Finally, we did not interview subjects regarding their perceptions of conflict, and therefore do not have qualitative information about the nature of the conflicts. This is an important area for future study.

Conclusions

In summary, we found that conflict between physicians and surrogates is prevalent in ICUs. However, there is little agreement between physicians and surrogates about whether conflict has occurred. There is a need for further work to develop reliable and valid methods to assess conflict. In the interim, future studies should assess conflict from the perspective of both clinicians and surrogates.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of funding: National Institutes of Health 1R01HL094553-01 (DBW), 5T32HL007563 (RAS)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Rachel A. Schuster, Program on Ethics and Decision Making in Critical Illness; Clinical Research, Investigation, and Systems Modeling of Acute Illness (CRISMA) Laboratory; Department of Medicine, Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, and Critical Care Medicine, University of Pittsburgh.

Seo Yeon Hong, Graduate School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh.

Robert M. Arnold, Department of Medicine, Division of General Internal Medicine, Section on Palliative Care and Medical Ethics, University of Pittsburgh.

Douglas B. White, Program on Ethics and Decision Making in Critical Illness; Clinical Research, Investigation, and Systems Modeling of Acute Illness (CRISMA) Laboratory; Department of Critical Care Medicine, University of Pittsburgh.

References

- 1.Abbott KH, Sago JG, Breen CM, Abernethy AP, Tulsky JA. Families looking back: One year after discussion of withdrawal or withholding of life-sustaining support. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(1):197–201. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200101000-00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azoulay E, Timsit J-F, Sprung CL, Soares M, Rusinova K, Lafabrie A, Abizanda R, Svantesson M, Rubulotta F, Ricou B, et al. Prevalence and factors of intensive care unit conflicts: the Conflicus study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:853–860. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200810-1614OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breen CM, Abernethy AP, Abbott KH, Tulsky JA. Conflict associated with decisions to limit life-sustaining treatment in intensive care units. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:283–289. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.00419.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meth ND, Lawless B, Hawryluck L. Conflicts in the ICU: Perspectives of administrators and clinicians. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:2068–2077. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1639-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Studdert DM, Mello MM, Burns JP, Puopolo AL, Galper BZ, Truog RD, Brennan TA. Conflict in the care of patients with prolonged stay in the ICU: types, sources, and predictors. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:1489–1497. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-1853-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Embriaco N, Azoulay E, Barrau K, Kentish N, Pochard F, Loundou A, Papazian L. High level of burnout in intensivists: prevalence and associated factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(7):686–692. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200608-1184OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poncet MC, Toullic P, Papazian L, Kentish-Barnes N, Timsit J-F, Pochard F, Chevret S, Schlemmer B, Azoulay E. Burnout syndrome in critical care nursing staff. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(7):698–704. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200606-806OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bergman T, Volkema R. Understanding and managing interpersonal conflict at work: its issues, interactive processes, and consequences. New York: Praeger; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ephross R, Vassil T. Social work with groups: Expanding horizons. Binghamton, NY: Haworth Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blake R, Mouton J. Solving costly organizational conflicts. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deutsch M. Sixty years of conflict. The International Journal of Conflict Management. 1990;1:237–263. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burns JP, Mello MM, Studdert DM, Puopolo AL, Truog RD, Brennan TA. Results of a clinical trial on care improvement for the critically ill. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(8):2107–2117. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000069732.65524.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jehn KA. A multimethod examination of the benefits and detriments of intragroup conflict. Adm Sci Q. 1995;40(2):256–282. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marcus LJ, Dorn BC, Kritek PB, Miller VG, Wyatt JB. Renegotiating Health Care: Resolving Conflict to Build Collaboration. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evans L, Boyd E, Malvar G, Apatira L, Luce JM, Lo B, White D. Surrogate decision-makers’ perspectives on discussing prognosis in the face of uncertainty. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:48–53. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200806-969OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abernethy A, Tulsky J. Disagreements that arise when making decisions about withdrawing or withholding life-sustaining treatment. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12(supplement 1):101. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Curtis J, Engelberg R, Nielsen E, Au D, Patrick D. Patient-physician communication about end-of-life care for patients with severe COPD. Eur Respir J. 2004;24:200–205. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00010104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dugan E, Trachtenberg F, Hall MA. Development of abbreviated measures to assess patient trust in a physician, a health insurer, and the medical profession. BMC Health Services Research. 2005;5:64. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-5-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krupat E, Rosenkranz S, Yeager C, Barnard K, Putnam S, Inui T. The practice orientations of physicians and patients: the effect of doctor-patient congruence on satisfaction. Patient Educ Couns. 2000;39:49–59. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(99)00090-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brush DR, Brown CE, Alexander GC. Critical care physicians' approaches to negotiating with surrogate decision makers: A qualitative study. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:1080–1087. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31823c8d21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McDonagh J, Elliott T, Engelberg R, Treece P, Shannon S, Rubenfeld G, Patrick D, Curtis J. Family satisfaction with family conferences about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: increased proportion of family speech is associated with increased satisfaction. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(7):1484–1488. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000127262.16690.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levinson W, Roter DL, Mullooly JP, Dull VT, Frankel RM. Physician-Patient Communication: The relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physicians and surgeons. JAMA. 1997;277(7):553–559. doi: 10.1001/jama.277.7.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stelfox HT, Gandhi TK, Orav EJ, Gustafson ML. The relation of patient satisfaction with complaints against physicians and malpractice lawsuits. The American Journal of Medicine. 2005;118(10):1126–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.