Abstract

Objectives

To investigate how bowel dysfunction after sphincter-preserving rectal cancer treatment, known as low anterior resection syndrome (LARS), is perceived by rectal cancer specialists, in relation to the patient's experience.

Design

Questionnaire study.

Setting

International.

Participants

58 rectal cancer specialists (45 colorectal surgeons and 13 radiation oncologists).

Research procedure

The Low Anterior Resection Syndrome Score (LARS score) is a five-item instrument for evaluation of LARS, which was developed from and validated on 961 patients. The 58 specialists individually completed two LARS score-based exercises. In Exercise 1, they were asked to select, from a list of bowel dysfunction issues, five items that they considered to disturb patients the most. In Exercise 2, they were given a list of scores to assign to the LARS score items, according to the impact on quality of life (QOL).

Outcome measures

In Exercise 1, the frequency of selection of each issue, particularly the five items included in the LARS score, was compared with the frequency of being selected at random. In Exercise 2, the answers were compared with the original patient-derived scores.

Results

Four of the five LARS score issues had the highest frequencies of selection (urgency, clustering, incontinence for liquid stool and frequency of bowel movements), which were also higher than random. However, the remaining LARS score issue (incontinence for flatus) showed a lower frequency than random. Scores assigned by the specialists were significantly different from the patient-derived scores (p<0.01). The specialists grossly overestimated the impact of incontinence for liquid stool and frequent bowel movements on QOL, while they markedly underestimated the impact of clustering and urgency. The results did not differ between surgeons and oncologists.

Conclusions

Rectal cancer specialists do not have a thorough understanding of which bowel dysfunction symptoms truly matter to the patient, nor how these symptoms affect QOL.

Keywords: Bowel dysfunction, Low anterior resection syndrome, Rectal cancer treatment, Patient-centred care, Clinical judgement, Quality of life

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to highlight the incongruity between the doctor's and the patient's perspective regarding bowel dysfunction following rectal cancer treatment.

The international mix and expert status of the specialists, the large nationwide cohort of Danish patients and the use of the validated Low Anterior Resection Syndrome Score underlie the validity of the results.

However, the generalisability of the results could be limited by the fact that the sample of specialists was drawn from five European colorectal conferences.

Introduction

In the past few decades, one of the most notable advancements in colorectal surgery has been the increasing use of sphincter-preserving procedures with a low colorectal or coloanal anastomosis.1 Such surgery avoids permanent colostomy, and has become the standard treatment for mid and low rectal cancers.2 However, many patients experience bothersome changes in bowel habits after the surgery, especially when it is combined with radiotherapy. These changes include faecal incontinence, frequent bowel movements, urgency and emptying difficulties. The complex of symptoms is referred to as ‘low anterior resection syndrome’ (LARS). LARS has been reported to affect up to 60–90% of patients who undergo low or ultralow anterior resection,3–6 and often compromises quality of life (QOL).5 7–10

Given the prevalence and impact on QOL of LARS, treating doctors should have an accurate understanding of the syndrome, so that patients can be adequately informed prior to treatment, as well as appropriately monitored and managed post-treatment. More importantly, doctors should have a good appreciation of how the patient views and experiences LARS, so that the information and care provided actually make a difference to the patient.

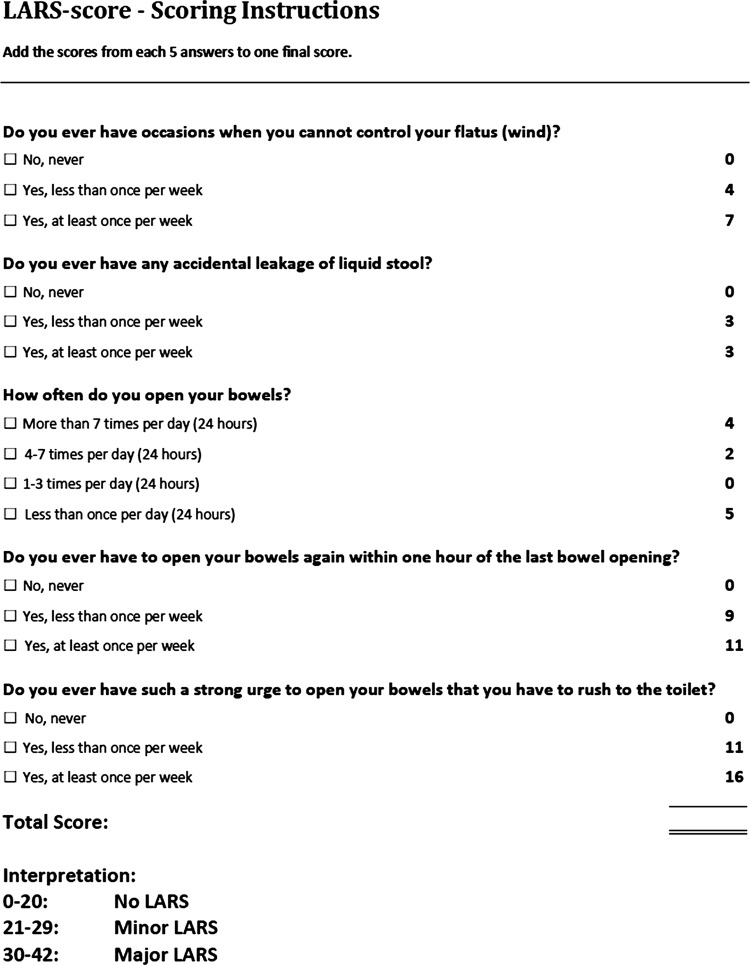

Our research group has devised the Low Anterior Resection Syndrome Score (LARS score), a concise scoring instrument for evaluation of bowel function after sphincter-preserving procedures with or without radiotherapy for rectal cancer.11 The content and scoring algorithm of the LARS score are shown in figure 1. The instrument has been developed from and validated on a nationwide cohort of 961 Danish patients, who received curative low anterior resection with or without radiotherapy for non-disseminated rectal cancer in Denmark between 2001 and 2007. The score has been designed to reflect the severity of bowel dysfunction symptoms and the impact on QOL. In addition to the original Danish version, the LARS score has been translated into several other languages (English, Dutch, Swedish, Spanish and German: validation is in progress for the former two, and the latter three have been validated in an international setting).12 Furthermore, we have recently observed an association between the LARS score and many of the scales of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core Module (EORTC QLQ-C30).13

Figure 1.

The Low Anterior Resection Syndrome Score (LARS score).

The aim of this study was to investigate the rectal cancer specialist's awareness of the patient's experience of LARS, using the LARS score.

Methods

Recruitment of specialists

Top specialist colorectal surgeons and radiation oncologists were approached at five European colorectal conferences in May and June 2012 (by author SL). These specialists were primarily keynote speakers, moderators or faculty members of the conference. They were first invited to participate in the study, and were then asked to nominate a colleague of the opposite specialty (a surgeon was asked to nominate an oncologist and vice versa), whom they usually work the closest with in managing rectal cancer. The nominated specialists were subsequently sent an email invitation in July and August 2012 to take part in the study.

Once a specialist agreed to participate, confirmation was sought regarding whether the specialist had seen the LARS score previously. A specialist was only eligible to take part if he or she had not seen the LARS score before. In addition, colorectal surgeons were asked to indicate whether they deal with functional bowel disorders on a regular basis.

Each specialist then proceeded to complete two exercises, as detailed below.

Data collection

Exercise 1

The LARS score consists of five questions, which were selected from a pool of items extracted from the existing bowel function assessment instruments and the current literature.11 By applying binomial regression on the response to these items obtained from half of the aforementioned cohort of Danish patients, the five questions (with at least one question representing each of the four known LARS symptom categories, namely incontinence, frequency, urgency and emptying difficulties) showing the highest prevalence and impact on QOL were identified.11

The purpose of Exercise 1 was to examine how well the specialist could recognise issues that patients find the most bothersome out of the range of LARS symptomatology. In this exercise, the specialist was presented with a list of 17 bowel dysfunction issues corresponding to the items in the original pool, along with a brief explanation similar to the one given above of how the five LARS score questions were chosen from this pool. The specialist was then asked to pick the five that he or she thought were selected for the LARS score.

Exercise 2

The score value of each response option of the LARS score questions indicates the extent to which it affects QOL. The higher the value, the higher the impact on QOL. The value is a derivative of the relative risk that the response option yielded in the binomial regression analysis.11

The purpose of Exercise 2 was to explore how well the specialist could estimate the degree of impact certain LARS symptoms pose on the patient's QOL. In this exercise, the specialist was presented with all the five LARS score questions and the 16 associated response options, where only the zero scores were shown. The specialist was also presented with a list of the 11 non-zero score values in ascending order, and a brief explanation similar to the one given above of how these values were established. The specialist was then asked to assign each score on the list to a response option that he or she deemed the most fitting.

Mode of exercise completion

Participating specialists completed the exercises individually, in sequential order (Exercise 1 followed by Exercise 2, where Exercise 2 was not revealed until Exercise 1 was completed), and in one of two ways. Those recruited at the conferences completed the exercises on paper, administered by one of the authors (SL) in person. Those recruited via email completed the exercises electronically, administered by one of the authors (TY-TC) via an internet teleconferencing session. All the materials were presented in English.

Statistical analysis

Exercise 1

For each of the 17 bowel dysfunction issues, the frequency of being selected by the specialists was calculated and compared with the expected frequency of being chosen if the specialists picked randomly. The number of specialists expected to correctly select the LARS score issues, if they picked randomly, was determined according to hypergeometric distribution. The number of specialists who actually chose the correct issues was calculated and compared with the expected number, using the χ2 test.

On the basis of our experience with LARS, we hypothesised that, in general, specialists would not be very good at judging what patients find the most bothersome, but should perform at least better than random.

Exercise 2

For each of the 11 non-zero score response options, the mean and distribution of the scores assigned by the specialists were calculated and compared with the original patient-derived score, using the one-sample Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Our hypothesis was that specialists would underestimate the impact of clustering (defined as having to open bowels again within 1 h of the last bowel opening).

Comparison between subgroups of specialists

Where appropriate, the results were compared between three subgroups of specialists: colorectal surgeons who deal with functional bowel disorders on a regular basis, colorectal surgeons who do not and radiation oncologists. We hypothesised that the results of surgeons who treat functional disorders would best approximate patient perception, whereas the results of oncologists would least approximate patient perception.

Using the independent samples Kruskal-Wallis test, the number of correct issues chosen was compared in Exercise 1, and the score value assigned was compared in Exercise 2.

All the statistical tests were conducted in IBM SPSS Statistics V.21. A p value of <0.01 was deemed statistically significant.

Results

Participating specialists

A total of 61 specialists were invited to take part in the study, and 58 (95%) participated. Of the three who did not participate, one was not eligible because he had previously seen the LARS score. The other two were eligible, but could not take part in the internet teleconferencing session due to time commitments.

The 58 participating specialists comprised 45 (78%) colorectal surgeons and 13 (22%) radiation oncologists. Of the 45 surgeons, 33 (73%) stated that they deal with functional bowel disorders on a regular basis and 12 (27%) stated to the contrary. The majority of the specialists practiced in Europe (52/58, 90%), while the remainder practiced in North America (4/58, 7%) and Asia (2/58, 3%).

Exercise 1

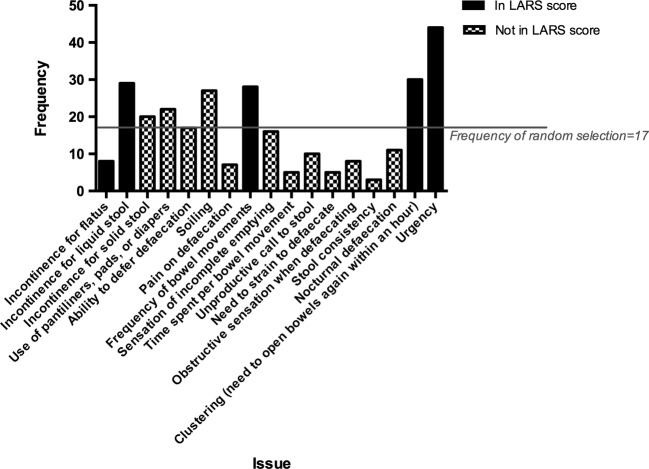

The frequency of selection of each of the 17 issues, as compared with the expected frequency of being chosen at random, is displayed in figure 2. Four of the five LARS score issues, namely urgency, clustering, incontinence for liquid stool and frequency of bowel movements (number of daily bowel movements), had the highest frequencies of selection, which were also clearly higher than the random frequency. However, the remaining LARS score issue of incontinence for flatus had a low frequency of selection that was markedly lower than random.

Figure 2.

Frequency of selection of each issue. The order of issues shown is the same as the order presented to the specialists.

Among issues that are not included in the LARS score, soiling had a high frequency of selection that was discernibly higher than random.

Table 1 shows the number of specialists correctly selecting the LARS score issues, as compared with the expected number if they picked at random. The specialists performed superior to random, with a significantly lower number choosing zero and one correct issue, and a significantly higher number choosing three correct issues. All 58 specialists picked at least one correct issue, but only one (2%) selected all the five issues correctly.

Table 1.

Observed and expected number of specialists selecting the correct issues

| Correct issues chosen | Expected number of specialists | Observed number of specialists | p Value of difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 7 | 0 | <0.01 |

| 1 | 23 | 9 | <0.01 |

| 2 | 21 | 23 | 0.70 |

| 3 | 6 | 21 | <0.01 |

| 4 | 1 | 4 | 0.17 |

| 5 | 0.009 | 1 | 0.32 |

Across all the participants, the median number of correct issues chosen was two of the five (mean 2.4, range 1–5). There was little variation in the number of correct issues selected between the subgroups (p=0.20).

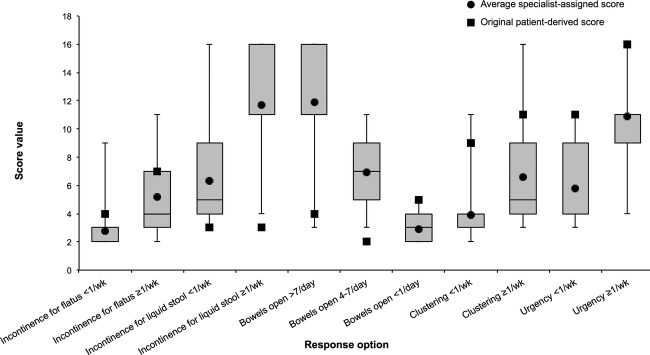

Exercise 2

The mean and distribution of the scores assigned by the specialists to each of the 11 response options, as compared with the original patient-derived score, are presented in figure 3. The assigned scores were significantly different from the original (p<0.01 for all 11 response options). The biggest discrepancies were seen in incontinence for liquid stool and frequent bowel movements (more than 7 times/day and 4–7 times/day), where the specialists grossly overestimated their impact on QOL. Conversely, the impact of clustering and urgency were markedly underestimated.

Figure 3.

Specialist and patient score of each response option.

There was little variation in the scores assigned between the subgroups (p values ranged from 0.06 to 0.97 among response options).

Discussion

This study has demonstrated that in general, rectal cancer specialists do not have a very thorough understanding of which bowel dysfunction symptoms truly matter to the patient after sphincter-preserving treatment, nor how these symptoms affect the patient's QOL, despite LARS being a prevalent and troublesome syndrome. Although the specialists performed better than random, there was considerable discrepancy between the specialist's perspective and patient experience. Few specialists recognise the importance of incontinence for flatus for the patient. Moreover, specialists tend to overestimate the impact of incontinence for liquid stool and frequent bowel movements, while underestimating the impact of urgency and clustering. Contrary to the hypothesised, no difference was found between the subgroups of specialists, which suggests that even clinicians who routinely deal with functional bowel disorders are not fully aware of the scope and impact of LARS. The fact that the participating specialists are highly regarded international experts on the treatment of rectal cancer further highlights the magnitude of the problem.

The LARS score is built on the collective viewpoint of 961 patients. It was formulated based on the experience of half of this cohort, and has been tested against QOL and clinical parameters on the other half of the cohort. It has a high sensitivity and specificity for identifying patients with majorly compromised QOL.11 It is also able to show differences between certain patient subgroups in ways that are consistent with clinical rationale.11 Therefore, the LARS score is a robust measure of the patient's perspective of LARS, and its use is the main strength of this study, as it underlies the validity of the results. On the other hand, the generalisability of the results could be limited by the sample of specialists recruited, since it is confined to five particular European colorectal conferences. However, given that the specialists are highly regarded international experts on the treatment of rectal cancer, it is unlikely that another or a larger specialist sample would generate results leading to different conclusions.

Numerous studies have previously reported the discrepancy between the clinician's judgement of patient perception and the patient's actual view or experience.14–23 These studies were conducted in the areas of symptom severity and QOL in urinary conditions; adverse effects of antipsychotic medications; QOL, anxiety, and depression in patients with cancer; disease activity, health status, functioning and outcomes in rheumatic diseases. The patient sample sizes in these studies were mostly smaller than our current study, and the doctor samples were largely poorly defined or quantified, unlike our study, which gives a clear description of the specialist sample. Furthermore, the doctors involved in these studies were the treating clinician of the participating patients, and not necessarily recognised experts in the field, as in our study. Validated questionnaires were used in several of the studies.14 16 20 21 23 Our current study is the first to document the incongruity between the doctor's and the patient's perspective regarding bowel dysfunction following rectal cancer treatment.

Not only is the specialist's knowledge of LARS crucial in the proper identification, assessment and management of the syndrome, it also underlies the specialist's ability to provide pertinent information to the patient prior to treatment. A recent population-based study showed that neoadjuvant therapy (short-course radiotherapy or long-course chemoradiotherapy) increased the risk of Major LARS by 2.5-fold.24 Even though radiation oncologists do not usually follow patients up after rectal cancer therapy, they should advise about the potential adverse effects that are the most concerning for the patient. Similarly, colorectal surgeons should also adequately inform patients before surgery, as well as review and attend to bothersome symptoms at follow-up. This study indicates that there is a need for improved clinician education of LARS. Moreover, the study supports the use of the LARS score in routine clinical practice. When assessing what is relevant to the patient and how the patient is affected, the patient's own rating should always be the gold-standard.25 26 The LARS score enables a patient-centred and standardised evaluation of LARS, which can guide the clinician in appropriately addressing the syndrome.27 Work is underway to incorporate the LARS score in routine follow-up after sphincter-preserving rectal cancer treatment in Denmark, Sweden and the Netherlands.

Prior to the development of the LARS score, several instruments for faecal incontinence had been used in various studies to measure incontinence in LARS patients, including the Wexner Incontinence Score, the Rockwood Faecal Incontinence Severity Index and the St Marks’ Faecal Incontinence Grading Score.28–36 This may have influenced the clinician to think that LARS is predominantly about faecal incontinence. In addition, the sizeable number of incontinence instruments available and the large volume of incontinence research to date indicate that faecal incontinence has been the main focus of bowel dysfunction in general. The emphasis on faecal incontinence may at least partially account for the substantial overestimation of the impact of incontinence for liquid stool and frequent bowel movements (which is closely related to incontinence) found in our study. The same may also explain the finding that soiling (which is not included in the LARS score) was chosen more frequently than incontinence for flatus (which is part of the LARS score). It is important to remember that LARS is a complex, multifaceted syndrome that involves more than just faecal incontinence and frequency. Clustering and urgency, which are the other aspects of the syndrome, should not be overlooked, especially when these are the symptoms that patients find the most bothersome, as revealed through the development of the LARS score (as shown in figure 1, clustering and urgency are the highest scoring questions in the LARS score).

We hope that this novel study serves to raise the awareness and improve the understanding of LARS among clinicians, and prompts a closer communication with the patient throughout the treatment and follow-up process. Further work is required to ensure the alignment of doctor and patient perception of LARS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Michael Væth for advice on statistical analysis, and the International Low Anterior Resection Syndrome Group for assistance with data collection. The following are members of the International Low Anterior Resection Syndrome Group: Herand Abcarian (USA), Richard Adams (UK), Matthew Albert (USA), Cornelius Baeten (the Netherlands), David Bartolo (UK), Willem Bemelman (the Netherlands), Sabine Bieri (Switzerland), Tom Cecil (UK), Andre D’Hoore (Belgium), Eelco de Graaf (the Netherlands), Ignace de Hingh (the Netherlands), Hans de Wilt (the Netherlands), Rainer Fietkau (Germany), Abe Fingerhut (France), Alois Fürst (Germany), Andrew Gaya (UK), Elisabeth Geijsen (the Netherlands), Michael Gerhards (the Netherlands), Bengt Glimelius (Sweden), Rob Glynne-Jones (UK), Karin Haustermans (Belgium), Richard (Bill) Heald (UK), Friedrich Herbst (Austria), Franc Hetzer (Switzerland), Werner Hohenberger (Germany), Torbjörn Holm (Sweden), Christoph Isbert (Germany), Lene Iversen (Denmark), Seon-Hahn Kim (South Korea), Sergio Larach (USA), Paul-Antoine Lehur (France), Jacob Lindegaard (Denmark), Hendrik Martijn (the Netherlands), Anna Martling (Sweden), Christoph Maurer (Switzerland), Brendan Moran (UK), Ronan O’Connell (Ireland), Michael (Mike) Parker (UK), Carlo Ratto (Italy), Eric Rullier (France), Reinhard Ruppert (Germany), Harm Rutten (the Netherlands), Thomas Schiedeck (Germany), Karl Søndenaa (Norway), Sigmar Stelzner (Germany), Angelo Stuto (Italy), Kenichi Sugihara (Japan), Diana Tait (UK), Emile Tan (UK), Pieter Tanis (the Netherlands), Paris Tekkis (UK), Vincenzo Valentini (Italy), Kurt Van Der Speeten (Belgium), Steven Wexner (USA), Joachim Widder (the Netherlands), Theo Wiggers (the Netherlands), Albert Wolthuis (Belgium), Evangelos Xynos (Greece).

Footnotes

Contributors: SL and TY-TC participated in the study conception and design. SL, TY-TC, KJE and all members of the International Low Anterior Resection Syndrome Group participated in acquisition of the data. TY-TC, SL and Michael Væth participated in analysis and interpretation of the data. TY-TC participated in drafting of the article. SL and KJE participated in critical revision of the article for important intellectual content. SL, KJE and TY-TC participated in the final approval of the published version. SL is the guarantor.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All the authors had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

- 1.Williamson MER, Lewis WG, Finan PJ, et al. Recovery of physiologic and clinical function after low anterior resection of the rectum for carcinoma. Dis Colon Rectum 1995;38:411–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stephens JH, Hewett PJ. Clinical trial assessing VSL#3 for the treatment of anterior resection syndrome. ANZ J Surg 2012;82:420–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kakodkar R, Gupta S, Nundy S. Low anterior resection with total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: functional assessment and factors affecting outcome. Colorectal Dis 2006;8:650–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ho YH, Low D, Goh HS. Bowel function survey after segmental colorectal resections. Dis Colon Rectum 1996;39:307–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Desnoo L, Faithfull S. A qualitative study of anterior resection syndrome: the experiences of cancer survivors who have undergone resection surgery. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2006;15:244–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Batignani G, Monaci I, Ficari F, et al. What affects continence after anterior resection of the rectum? Dis Colon Rectum 1991;34:329–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grumann MM, Noack EM, Hoffmann IA, et al. Comparison of quality of life in patients undergoing abdominoperineal extirpation or anterior resection for rectal cancer. Ann Surg 2001;233:149–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Camilleri-Brennan J, Steele RJC. Quality of life after treatment for rectal cancer. Br J Surg 1998;85:1036–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Camilleri-Brennan J, Ruta DA, Steele RJC. Patient generated index: new instrument for measuring quality of life in patients with rectal cancer. World J Surg 2002;26:1354–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pachler J, Wille-Jørgensen P. Quality of life after rectal resection for cancer, with or without permanent colostomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;18:CD004323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emmertsen KJ, Laurberg S. Low Anterior Resection Syndrome Score: development and validation of a symptom-based scoring system for bowel dysfunction after low anterior resection for rectal cancer. Ann Surg 2012;255:922–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Juul T, Ahlberg M, Biondo S, et al. International validation of the Low Anterior Resection Syndrome Score. Ann Surg Published Online First: 17 April 2013. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31828fac0b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Juul T, Ahlberg M, Biondo S, et al. Low anterior resection syndrome and quality of life—an international multicenter study. Dis Colon Rectum Submitted: 9 May 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nosè M, Mazzi MA, Esposito E, et al. Adverse effects of antipsychotic drugs: survey of doctors’ versus patients’ perspective. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2012;47:157–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Platt FW, Keating KN. Differences in physician and patient perceptions of uncomplicated UTI symptom severity: understanding the communication gap. Int J Clin Pract 2007;61:303–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Slevin ML, Plant H, Lynch D, et al. Who should measure quality of life, the doctor or the patient? Br J Cancer 1988;57:109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hewlett SA. Patients and clinicians have different perspectives on outcomes in arthritis. J Rheumatol 2003;30:877–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tucker MK, Brigio FD, Sirotenko GA, et al. A ‘gap’ between physician and patient assessment of symptom severity in acute cystitis?: a multicenter trial of women treated with extended-release ciprofloxacin. Postgrad Med 2004;116:11–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwoh CK, O'Connor GT, Regan-Smith MG, et al. Concordance between clinician and patient assessment of physical and mental health status. J Rheumatol 1992;19:1031–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berkanovic E, Hurwicz ML, Lachenbruch PA. Concordant and discrepant views of patients’ physical functioning. Arthritis Care Res 1995;8:94–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suarez-Almazor ME, Conner-Spady B, Kendall CJ, et al. Lack of congruence in the ratings of patients’ health status by patients and their physicians. Med Decis Making 2001;21:113–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neville C, Clarke AE, Joseph L, et al. Learning from discordance in patient and physician global assessments of systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity. J Rheumatol 2000;27:675–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodríguez LV, Blander DS, Dorey F, et al. Discrepancy in patient and physician perception of patient's quality of life related to urinary symptoms. Urology 2003;62:49–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bregendahl S, Emmertsen KJ, Lous J, et al. Bowel dysfunction after low anterior resection with and without neoadjuvant therapy for rectal cancer: a population-based cross-sectional study. Colorectal Dis 2013;15:1130–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Streiner DL, Norman GR. Health measurement scales: a practical guide to their development and use. 4th edn New York: Oxford University Press, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 26.McDowell I. Measuring health: a guide to rating scales and questionnaires. 3rd edn Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stewart M. Towards a global definition of patient centred care: the patient should be the judge of patient centred care. BMJ 2001;322:444–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gosselink MP, West RL, Kuipers EJ, et al. Integrity of the anal sphincters after pouch-anal anastomosis: evaluation with three-dimensional endoanal ultrasonography. Dis Colon Rectum 2005;48:1728–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chamlou R, Parc Y, Simon T, et al. Long-term results of intersphincteric resection for low rectal cancer. Ann Surg 2007;246:916–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bittorf B, Stadelmaier U, Göhl J, et al. Functional outcome after intersphincteric resection of the rectum with coloanal anastomosis in low rectal cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 2004;30:260–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bretagnol F, Rullier E, Laurent C, et al. Comparison of functional results and quality of life between intersphincteric resection and conventional coloanal anastomosis for low rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 2004;47:832–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matzel KE, Stadelmaier U, Bittorf B, et al. Bilateral sacral spinal nerve stimulation for fecal incontinence after low anterior rectum resection. Int J Colorectal Dis 2002;17:430–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pucciani F, Ringressi MN, Redditi S, et al. Rehabilitation of fecal incontinence after sphincter-saving surgery for rectal cancer: encouraging results. Dis Colon Rectum 2008;51:1552–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Welsh F, McFall M, Mitchell G, et al. Pre-operative short-course radiotherapy is associated with faecal incontinence after anterior resection. Colorectal Dis 2003;5:563–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gosselink MP, Zimmerman DD, West RL, et al. The effect of neo-rectal wall properties on functional outcome after colonic J-pouch-anal anastomosis. Int J Colorectal Dis 2007;22:1353–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rockwood TH, Church JM, Fleshman JW, et al. Patient and surgeon ranking of the severity of symptoms associated with fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 1999;42:1525–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.