Abstract

Objectives

The study objective was to determine the feasibility of using a pharmacist-staffed, protocol-based structured approach to improving the management of chronic, recurrent gout.

Setting

The study was carried out in the outpatient clinic of a single Kaiser Permanente medical centre. This is a community-based clinic.

Participants

We report on 100 consecutive patients between the ages of 21 and 94 (75% men) with chronic or recurrent gout, referred by their primary physicians for the purpose of management of urate-lowering therapy. Patients with stage 5 chronic kidney disease or end-stage kidney disease were excluded.

Interventions

The programme consisted of a trained clinical pharmacist and a rheumatologist. The pharmacist contacted each patient by phone, provided educational and dietary materials, and used a protocol that employs standard gout medications to achieve and maintain a serum uric acid (sUA) level of 6 mg/dL or less. Incident gout flares or adverse reactions to medications were managed in consultation with the rheumatologist.

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome measure was the achievement and maintenance of an sUA of 6 or less for a period of at least 3 months.

Results

In 95 evaluable patients enrolled in our pilot programme, an sUA of 6 mg/dL or less was achieved and maintained in 78 patients with 4 still in the programme to date. Five patients declined to participate after referral, and another 13 patients did not complete the programme. (The majority of these were due to non-adherence.)

Conclusions

A structured pharmacist-staffed programme can effectively and safely lower and maintain uric acid levels in a high percentage of patients with recurrent gout in a primary care setting. This care model is simple to implement, efficient and warrants further validation in a clinical trial.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The population we studied is representative of patients with gout seen in general rheumatology practice, and therefore our results should be widely generalisable. Our programme is relatively easy to implement and requires only a trained clinical pharmacist and rheumatologist to carry out.

Although encouraging, this pilot study does not prove that our gout management programme is more effective than usual care for gout because there was no control group. A study testing this hypothesis is needed.

The structure of our organisation, which integrates the health plan, pharmacy programmes and physician care, is optimal for the use of our programme. A nonintegrated system might lead to barriers in setting up a similar collaboration. This may limit the applicability of the model.

Introduction

Gout is the most common inflammatory arthritis in men1 and results in considerable morbidity and utilisation of healthcare resources.2 The past 30 years have witnessed a steady increase in the prevalence of gout.3–5 The causes of this rise in gout prevalence appear to be linked to the increasing prevalence of obesity, diabetes, chronic renal disease and hypertension.6 7 Unlike other common rheumatic diseases, the underlying cause of gout, chronic elevation of serum uric acid (sUA), is well understood.

The current approaches for management of other common chronic conditions, such as diabetes, are based on the principle that chronic illnesses are best managed by identifying the predictors of optimal outcomes, setting treatment targets and then monitoring for success in treating to the targets.8 In the case of gout, an appropriate treatment target has been identified by expert panels sponsored by the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR)9 and the American College of Rheumatology.10 Both recommend that patients with tophaceous or recurrent gout be treated with urate-lowering therapy (ULT) to a target sUA of <6 mg/dL. Unfortunately, only a minority of patients with gout receives appropriate treatment, including doses of ULT sufficient to achieve this target.11 There are several reasons for this deficiency which have been addressed by other authors.12 13 The reasons cited have included a lack of appropriate monitoring, failure to treat-to-target and fear of escalation of ULT in some patients, particularly patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Taken together, it appears that there is a great need for improved approaches to the management of gout.

To address the problem of inadequate management of gout, we developed a model for gout management consisting of a ‘virtual’ clinic comprised of a clinical pharmacist under the supervision of a board-certified rheumatologist (RG). Following a written protocol, the pharmacist initiates, adjusts and monitors the use of standard gout medications for patients referred by their primary care physicians for recurrent or tophaceous gout. Patients are followed by the clinic until they have two consecutive target sUA results at least 3 months apart, and are then discharged back to their usual care. We report here the results of a pilot programme by presenting the outcomes of the first 100 patients referred to the programme. Though a limited intervention, our intent was to address some of the issues identified in the literature and perform it in a way that is highly leveraged and potentially suitable for a large majority of patients with chronic gout who are currently not being adequately managed.

Methods

Patient referral

Patients with gout whose primary care physicians practice at Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) in Richmond, California were eligible for referral to the gout management programme. Referral was at the discretion of the primary care physician (sometimes in consultation with the rheumatologist (RG)), based on a history of recurrent or tophaceous gout and the intent to use ULT. Referring physicians were offered the choice of referring each patient for a formal rheumatology consultation, or to the gout management programme, supervised by the same rheumatologist. The clinical pharmacist then telephoned the referred patients, introduced them to the protocol and, if they agreed to participate, entered them into the programme. Patients consenting to treatment in the programme were provided written educational material including dietary guidelines at the time of programme entry. Patients with end-stage renal disease were excluded from the programme. The pharmacist, under a protocol approved by the Kaiser Permanente East Bay Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee, was authorised to order relevant laboratory tests and initiate or change orders for the medications used to manage sUA and for flare prophylaxis. For treatment of acute flares, medication orders were sometimes provided by the rheumatologist if outside the scope of the pharmacy protocol.

Laboratory assessment and monitoring

Baseline laboratory assessment performed on all referred patients consisted of an sUA, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and complete blood count (CBC). This same panel of laboratory tests was repeated as needed to monitor the progress while the patient was enrolled in the gout management clinic.

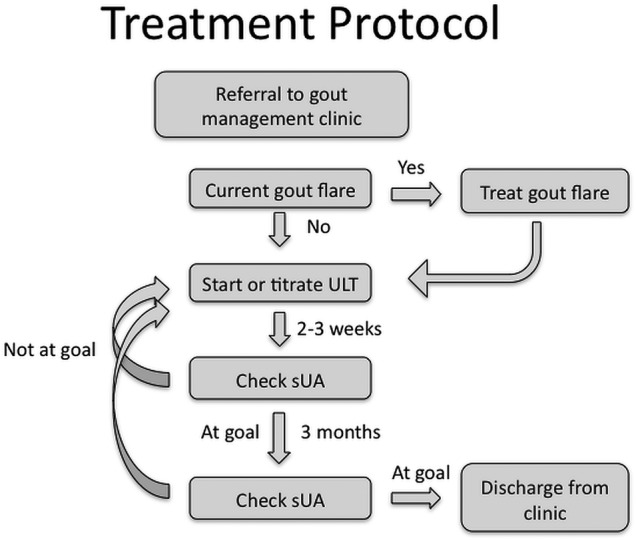

Treatment protocol

Figure 1 is a schematic diagram of the assessment and treatment protocol. Once entered into the programme, baseline laboratory assessment was performed if not available within the prior month. If, at the time of referral, a patient was being treated for an acute flare of gout, this treatment was continued and completed. Once a baseline laboratory assessment was available, ULT was either initiated or adjusted if the sUA was above 6 mg/dL. Flare prophylaxis was used in all cases (see below). After any change in ULT, the patient was instructed to return for laboratory assessment (sUA, ALT, CBC and eGFR) in 2 weeks, and report any adverse drug reactions (ADRs) or gout symptoms. ADRs or gout flares were managed by the clinical pharmacist, usually in consultation with the supervising rheumatologist. This process was continued in an iterative fashion until a target sUA of ≤6 mg/dL was achieved. Patients at target were asked to repeat the laboratory assessment in 3 months. At that time, patients still at target were discharged from the clinic and instructed to continue their medications and follow-up with their primary care physician. Those who were not at target were either restarted on their ULT or it was titrated and the level was re-tested in 2 weeks. Patients remained in the gout management programme until they demonstrated two sUAs <6 mg/dL at least 3 months apart.

Figure 1.

Clinic monitoring and treatment flow diagram. sUA, serum uric acid; ULT, urate-lowering therapy.

Pharmacological treatments

ULT was initiated with allopurinol in all patients as first-line therapy unless the patient had a known ADR or allergy to allopurinol. The starting dose for allopurinol-naïve patients was 100 mg daily (some patients were on higher doses at the time of referral). Dose titration for patients not at target sUA was performed using 100 mg/day increments, or in some cases, although selected patients on 300 mg daily were titrated to 450 mg daily. The maximum allopurinol dose used in the programme was 600 mg/day. Patients already on febuxostat or probenecid were maintained on these and the doses were titrated as needed based on sUA. Patients who developed a significant ADR or symptoms of allergy to allopurinol were switched to either febuxostat 40 mg daily or probenecid 500 mg daily, depending on their clinical status in consultation with the rheumatologist. Dose titration was then continued with these drugs if needed.

Gout-flare prophylaxis was used in all patients, and in most of the instances, we utilised colchicine 0.6 mg daily. For patients with eGFR less than 30, the dose was reduced to 0.3 mg/day. In some patients, if recommended by the rheumatologist, a daily non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) treatment was substituted, if no contraindication prevented this.

Acute gout flares were managed by the clinical pharmacist, in consultation with the rheumatologist, using oral NSAIDS, prednisone or colchicine.

ADR to medications, incident gout flares and abnormal laboratory parameters were recorded by the clinical pharmacist at each telephone encounter and were reviewed by the rheumatologist for management.

Results

The patient demographics and comorbidities of the pilot sample are described in table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients (N=100)

| Characteristic | Mean (range) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 61 (32–94) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 31 (20–48) |

| Per cent | |

| Male | 75 |

| Hypertension | 75 |

| Chronic kidney disease (2–4) | 29 |

| Diabetes | 29 |

| Coronary artery disease | 10 |

| Congestive heart failure | 11 |

| Two or more comorbidities | 46 |

Three-fourths of the patients were men. The mean age was 61 years (range 32–94 years). The mean body mass index was 31 kg/m2 (range 20–48 kg/m2). Common gout-associated comorbidities were determined based on the presence of specific International Classification of Diseases 9 codes listed in the problem list of each patient in the electronic medical record, and verified by chart review. The majority of patients had at least one of the common comorbidities associated with gout. Seventy-five per cent of the patients had hypertension and 29% had CKD. Of these, 2 had stage 2 CKD, 22 had stage 3 CKD and 3 had stage 4 CKD. Another 29% had diabetes. A smaller number of the patients had either coronary artery disease or congestive heart failure. Forty-six per cent of the patients had two or more of these comorbid conditions.

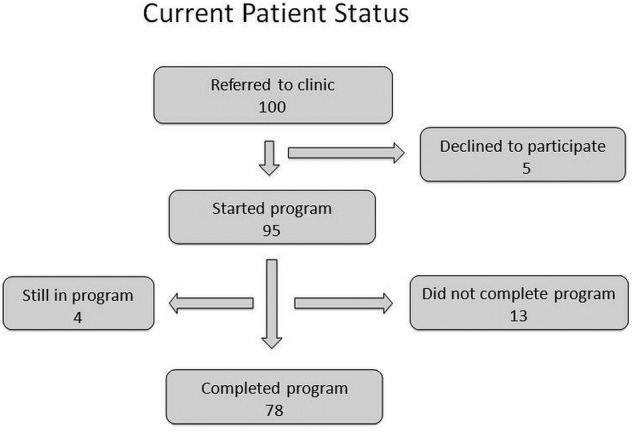

Figure 2 is a schematic that shows the current status of the first 100 patients referred to our clinic. Five patients declined to participate when initially contacted by the pharmacist. Thus, 95 patients started the programme, and at the time of this analysis, 78 had completed the programme with two consecutive sUA measurements of <6 mg/dL, and 4 were still being managed. Thirteen patients left the programme prior to achieving the end point. Of these, two patients died while in the programme. One died from complications of abdominal surgery and the other, aged 94, died at home of ‘natural causes’. One patient developed symptoms of an allergic reaction to allopurinol and declined further treatment. One patient lost insurance coverage, and another was incarcerated. The remaining eight patients were discharged by the programme pharmacist because of a pattern of non-adherence to treatment or lab monitoring, or because they elected not to complete the programme. The time patients spent under programme management varied considerably. The mean duration of participation was 47.8 weeks (range 14.9–109.6 weeks). Although our programme was a feasibility study and designed as a short-term intervention, when we examined the medical records of the 78 patients who have successfully completed the programme, we found that 63 of them had been tested at least one time by their regular physician after clinic discharge (mean follow-up time 36 weeks) and 53 patients (80%) still maintained an sUA of 6 or less.

Figure 2.

The current status of first 100 patients referred to the programme.

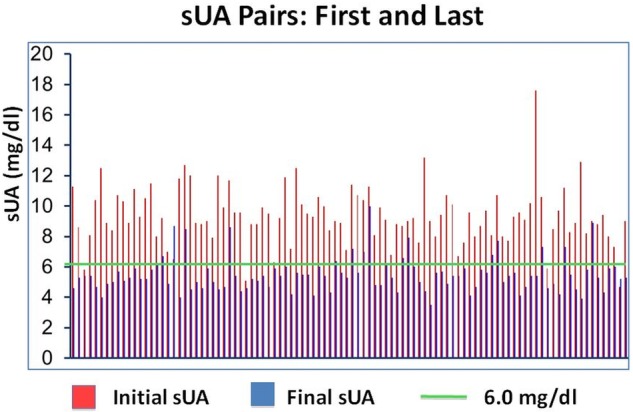

Figure 3 shows the sUA’s of each patient in the pilot gout-management study as a set of paired samples. Each pair of bars represents the baseline sUA (red bars) and final sUA (blue bars) for each patient. For those patients still in the programme, or who failed to complete the programme, the blue bar is the most recent sUA available. The dotted horizontal line represents the sUA target of 6 mg/dL. The figure shows all the patients who entered the programme, including those who are still being managed and those who did not complete the programme.

Figure 3.

Comparison of pretreatment serum uric acid (sUA) and most recent or final sUA. Each patient is represented by a red bar (initial sUA) and a blue bar (final sUA, whether or not he/she completed the programme).

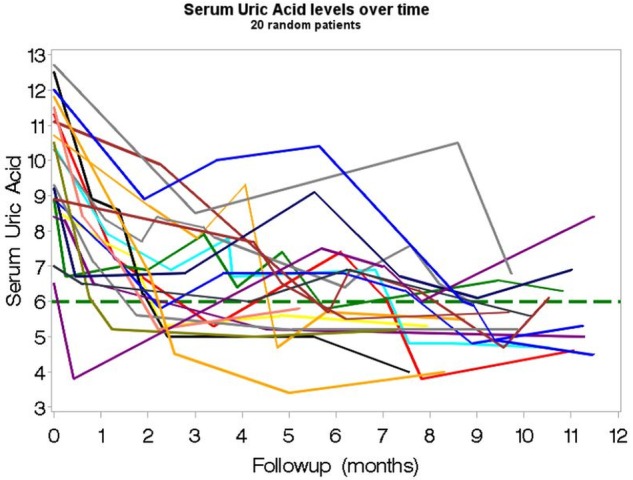

To provide a more detailed view of how patients responded to management by the clinic, we plotted sequential sUA levels in a subset of our patients. Figure 4 shows this analysis in 20 randomly selected patients entering the programme. Each line represents the sequential sUA measurements of a single patient for a period of 12 months. Essentially all the patients in this random sample initially responded with a significant reduction in sUA. In many patients, this improvement was sustained, but in others, the sUA subsequently rose due to discontinuation of ULT. In these patients, the pharmacist was able, in most cases, to restart ULT and continue testing to assure continuing medication adherence. The figure also shows that by 12 months in the programme, 16 of the 20 patients had achieved a target sUA and 2 had a normal sUA of <6.8 mg/dL.

Figure 4.

Serum uric acid (sUA) trend lines for 20 randomly selected patients. Each coloured line represents sequential sUA levels in a single patient. Each line stops at the time of clinic discharge or is the most recent sUA if the patient had not completed or left the programme.

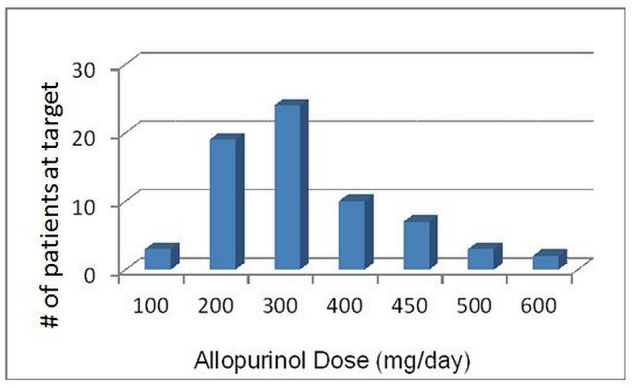

Analysis of the 78 patients who have completed the programme after achieving and maintaining the targeted sUA showed that 68 patients (87%, 95% CI 78% to 94%) were on allopurinol at discharge. Figure 5 shows the distribution of allopurinol doses required to achieve an sUA of ≤6. The mean daily allopurinol dose required to achieve an sUA of ≤6 was 311 mg. Sixty-eight per cent of patients on allopurinol achieved the target on 300 mg/day or less. Only three patients achieved the goal on the starting dose of 100 mg daily and two patients required 600 mg/day. All five patients on febuxostat had achieved the goal of sUA level on 40 mg/day.

Figure 5.

Dose of allopurinol required to achieve a serum uric acid of ≤6 mg/dL.

Three patients (3%) experienced rash or other symptoms of allergy to allopurinol. None required more than discontinuation of the medication. Of these, two patients were changed to alternative ULT and one patient declined further treatment and discontinued the programme. Elevation of ALT was seen at some time during treatment in 47 patients (48%), but only 7 of the patients had elevations high enough to require changing medication. Most of the patients stabilised or returned to normal with continued treatment and monitoring. Incident acute gout flares were reported in 33 patients (34%). None resulted in discontinuation of ULT. Gastrointestinal side effects were uncommon and in no case required a change in therapy.

Discussion

Gout is arguably the best understood of the common inflammatory arthritic diseases; effective preventive therapy is readily available and the key outcome (sUA <6 mg/dL in most cases) is easily measured. Why, then, is unsuccessful control of sUA so frequent? A number of factors contribute to suboptimal gout management.11 12 14 Adherence to ULT is poor when compared with medication adherence in other chronic conditions.15 Symptoms are typically intermittent with extended gout-free periods. Moreover, there are effective treatments for gout flares and medications (eg, colchicine) that can reduce the incidence of flares without lowering sUA. It is not surprising, therefore, that many patients with gout are never started on, or discontinue, ULT. Another important feature of gout management is that initiation of ULT can lead to a short-term increase in the incidence of gout flares,16 further discouraging the continuation of therapy. Better patient education could be expected to improve a long-term medication adherence, but is not consistently provided.17 While diet is clearly a factor in the development of gout,18 patients and physicians frequently place a disproportionate emphasis on dietary restrictions.19 Although consensus guidelines recommend treating with ULT to a target sUA of 6 mg/dL or less, concerns about allopurinol toxicity may discourage some physicians from achieving this goal. In particular, limiting doses of allopurinol in patients with CKD lead to a high percentage of treatment failures.20 Finally, many clinical laboratories do not correctly identify serum urate concentrations of >6.8 mg/dL as being abnormal. This leads to undertreatment and considerable confusion about diagnosis and management.21

Our pilot programme was conceived as a way to reframe the approach to gout management. We hypothesised that using a structured treat-to-target approach with regular monitoring and a goal-directed intervention would result in a high percentage of patients achieving a target sUA. In particular, the protocol was designed to use a slow titration of ULT along with flare prophylaxis and scheduled follow-up calls. We also required sustained control of sUA for at least 3 months as a way to promote longer term medication adherence. We realise that maintaining the treatment for 3 months does not guarantee a long-term control of sUA. Nevertheless, of the patients for whom a follow-up test was available, 80% were still at target, a mean of 36.8 weeks after clinic discharge. As for any chronic condition, optimal outcomes will require some level of structured monitoring.

The results of our pilot programme suggest that a structured programme may be an effective approach to gout management. ULT medications are highly effective, and therefore almost all our patients responded with significant reductions in sUA within weeks of starting the programme (figure 4). Dose titration allowed most of the patients to achieve a target sUA of <6 mg/dL and, to-date, all the patients have been able to achieve the goal using standard doses of available medications. The demographic and clinical features of the patients in our gout sample were similar to those seen in the general population of patients with gout described in previous studies,22 suggesting that our findings should be generalisable to gout populations outside KPNC. A nurse-staffed case management approach has been used and achieved impressive results in controlling sUA in patients with gout.23 Our pilot programme is also based on a structured management approach, but did not require any clinic visits. This model is highly efficient and therefore suitable for managing a large population of patients with gout, but not necessarily more effective than a case management approach.

There is ample evidence that therapeutic inertia contributes to inadequate results of ULT.24 Our programme was designed specifically to counter this problem by including repeated sUA measurements and specified actions based on the results. In addition, our protocol did not limit the doses of allopurinol specifically based on renal function, which has been one of several impediments noted in the literature to a successful ULT. The current recommendations do not support the need to limit allopurinol doses to 100 mg daily in patients with CKD,25–27 though a low-starting dose and slow titration are recommended.26 28 Indeed, limiting the dose of allopurinol based on the presence of CKD has been shown to result in treatment failure in an unacceptably high percentage of patients.17 Our data confirm this observation: only 3 of 68 allopurinol-treated patients (4%) completing the programme achieved an sUA of ≤6 on 100 mg daily of allopurinol, and only 68% achieved the target with 300 mg daily (figure 5).

Not surprisingly, we encountered many cases of medication non-adherence. In most of the cases, this was detected in the course of the routine testing that comprised the protocol. Typically, a patient whose sUA was at or near target, had a repeat test that was no longer at target. In some cases, non-adherence was discovered at the time the patient called to pharmacist because of a gout flare. Our protocol, by requiring two consecutive target sUA levels 3 months apart, was designed with the expectation that adherence to ULT would be inconsistent. As noted previously, we do not know whether our time-limited intervention will ultimately lead to a long-term control of sUA in these patients, but we were able to detect medication non-adherence in the first few months and thus reinforce the importance of a long-term ULT. Ideally, monitoring of sUA would continue on a regular basis, as recommended for relevant laboratory parameters in other chronic conditions. Despite the fact that all the patients were prescribed colchicine or NSAIDs for flare prophylaxis, we encountered a substantial number of gout flares during the programme. While some increase in flares may be expected, in our experience, many of the flares in our patients occurred in connection with medication non-adherence. This tendency of patients with gout to discontinue ULT accounted for the wide range of times patients had to stay under management. We provided our patients with written educational material as well, but could not evaluate the effectiveness of this.

We designed our pilot study to be efficient and cost-effective by leveraging physician time. The gout management programme, while supervised by a board-certified rheumatologist, was staffed by a clinical pharmacist who was carefully trained in the management protocol. The pharmacist was able to manage a cohort of up to about 80 patients at a time while spending only about 6–8 h/week. The time spent in overseeing and assisting the clinical pharmacist was never more than about 30 min/week while supervised by a board-certified rheumatologist once the programme was in place. Moreover, our programme did not require any in-person visits. This model suggests a path to improved outcomes in patients with gout without generating the magnitude of increased utilisation of healthcare resources that might otherwise be required. We recognise that pharmacists may not be available or allowed to manage patients as was performed in our protocol. Even so, a trained clinical nurse could be substituted in the pharmacist's role and provide excellent care while leveraging physician time.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: RDG conceived and developed the protocol and programme. He also participated in collection and analysis of data, and pharmacist supervision. ALA consulted on project design, data capture, statistical methods and manuscript editing. AP oversaw the data analysis and presentation, and consulted on data analysis and manuscript editing. AH oversaw the development and approval of treatment protocol and supervised clinical pharmacists. AJ assisted with the data collection and analysis. MSN and GY worked directly with participants to arrange data collection, adjust medications, obtain clinical information and report issues or concerns with supervising rheumatologist.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States: part II. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:26–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krishnan E, Lienesch D, Kwoh CK. Gout in ambulatory care settings in the United States. J Rheumatol 2008;35:498–501 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wallace KL, Riedel AA, Joseph-Ridge N, et al. Increasing prevalence of gout and hyperuricemia over 10 years among older adults in a managed care population. J Rheumatol 2004;31:1582–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arromdee E, Michet CJ, Crowson CS, et al. Epidemiology of gout: is the incidence rising? J Rheumatol 2002;29:2403–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kramer HN, Curhan G. The association between gout and neprholithiasis: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III. Am J Kidney Dis 2002;40:37–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weaver AL. Epidemiology of gout. Cleve Clin J Med 2008;75(Supp 5):9–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Annemans L, Spaepen E, Gaskin M, et al. Gout in the UK and Germany: prevalence, comorbidities and management in general practice 2000–2005. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:960–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peters AL, Davidson MB. Application of a diabetes managed care program. The feasibility of using nurses and a computer system to provide effective care. Diabetes Care 1998;21:1037–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang W. EULAR evidence based recommendations for gout. Part II: Management. Report of a task force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis 2006;65:1312–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khanna D, Fitzgerald JD, Khanna PP, et al. 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 1: systematic nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapeutic approaches to hyperuricemia. Arthritis Care Res 2012;64:1431–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edwards NL. Quality of care in patients with gout: why is management suboptimal and what can be done about it? Curr Rheumatol Rep 2010;13:154–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pascual E, Sivera F. Why is gout so poorly managed? Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:1269–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh JA, Hodges JS, Toscano JP, et al. Quality of care for gout in the US needs improvement. Arthritis Rheum 2007;57:822–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Becker MA, Chohan S. We can make gout management more successful now. Curr Opin Rheum 2008;20:167–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Briesacher BA, Andrade SE, Fouayzi H, et al. Comparison of drug adherence rates among patients with seven different medical conditions. Pharmacotherapy 2008;28:437–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schumacher HR, Becker MA, Lloyd E, et al. Febuxostat in the treatment of gout: 5-yr findings of the FOCUS efficacy and safety study. Rheumatology 2008;48:188–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi HK, Atkinson K, Karlson EW, et al. Purine-rich foods, dairy and protein intake, and the risk of gout in men. N Engl J Med 2004;350:1093–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doherty M, Jansen TL, Nuki G, et al. Gout: why is this curable disease so seldom cured? Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:1765–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dalbeth N, Kumar S, Stamp L, et al. Dose adjustment of allopurinol according to creatinine clearance does not provide adequate control of hyperuricemia in patients with gout. J Rheumatol 2006;33:1646–50 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mandell BF. Confessions of a goutophile: despite its treatability, gout remains a problem. Cleve Clin J Med 2008;75(Suppl 5):S1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim KY, Ralph Schumacher H, Hunsche E, et al. A literature review of the epidemiology and treatment of acute gout. Clin Ther 2003;25:1593–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trifiro G, Morabito P, Cavagna L, et al. Epidemiology of gout and hyperuricaemia in Italy during the years 2005–2009: a nationwide population-based study. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;72:694–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rees F, Jenkins W, Doherty M. Patients with gout adhere to curative treatment if informed appropriately: proof-of-concept observational study. Ann Rheum Dis 2012. [cited 2013 Apr 12]. http://ard.bmj.com/cgi/doi/10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liote F, Choi H. Managing gout needs more than drugs: ‘II faut le savoir-faire, I’Art et la maniere’. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:791–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stamp LK, O'Donnell JL, Zhang M, et al. Using allopurinol above the dose based on creatinine clearance is effective and safe in patients with chronic gout, including those with renal impairment. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:412–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chao J, Terkeltaub R. A critical reappraisal of allopurinol dosing, safety, and efficacy for hyperuricemia in gout. Curr Rheum Rep 2009;11:135–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim SC, Newcomb C, Margolis D, et al. Severe cutaneous reactions requiring hospitalization in allopurinol initiators: a population-based cohort study. Arthritis Care Res 2013;65:578–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dalbeth N, Stamp L. Allopurinol dosing in renal impairment: walking the tightrope between adequate urate lowering and adverse events. Semin Dial 2007;20:391–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.