Smooth muscle cells (SMCs) and endothelial cells (ECs) are typically derived separately, with low efficiencies, from human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs). The concurrent generation of these cell types might have potential applications in regenerative medicine model, elucidate, and eventually treat vascular diseases. This study reports a robust, two-step protocol that can be used to generate large numbers of functional SMCs and ECs simultaneously from a common proliferative vascular progenitor population via a two-dimensional culture system.

Keywords: Stem cell, Embryonic stem cells, Endothelial cells, Smooth muscle cells

Abstract

Smooth muscle cells (SMCs) and endothelial cells (ECs) are typically derived separately, with low efficiencies, from human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs). The concurrent generation of these cell types might lead to potential applications in regenerative medicine to model, elucidate, and eventually treat vascular diseases. Here we report a robust two-step protocol that can be used to simultaneously generate large numbers of functional SMCs and ECs from a common proliferative vascular progenitor population via a two-dimensional culture system. We show here that coculturing hPSCs with OP9 cells in media supplemented with vascular endothelial growth factor, basic fibroblast growth factor, and bone morphogenetic protein 4 yields a higher percentage of CD31+CD34+ cells on day 8 of differentiation. Upon exposure to endothelial differentiation media and SM differentiation media, these vascular progenitors were able to differentiate and mature into functional endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells, respectively. Furthermore, we were able to expand the intermediate population more than a billionfold to generate sufficient numbers of ECs and SMCs in parallel for potential therapeutic transplantations.

Introduction

Successful differentiation of human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) as well as human induced pluripotent stem cells into desired lineages has opened doors for potential applications in cell therapy for regenerative medicine. Vascular regeneration via novel cell-based therapies is a promising strategy for treating ischemic diseases; however, it is not adequate to replace endothelial cells (ECs) alone [1, 2]. Both ECs and vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs) are indispensable for the development of a mature and durable vasculature [3]. Thus, there is a need for simultaneous generation of ECs and SMCs in order to realize potential cell replacement therapies.

Cells that have marker profiles of CD31+CD34+ and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2+ (VEGFR2+) are known to form a vascular plexus that gives rise to the dorsal aorta, the cardinal vein, and the embryonic stems of yolk sac arteries and veins [3]. Vascular SMCs arise from multiple independent origins during development [4], and it has been shown that coronary SMCs originate from the proepicardial organ, which is of lateral plate mesodermal origin [5]. Hence, we hypothesized that CD31+CD34+ cells act as vascular progenitor cells and can be further differentiated into endothelial and smooth muscle cells, respectively, by exposure to specific growth factors. Indeed, Bai et al. demonstrated that hESC-derived CD34+CD31+ cells contain a population of vascular progenitor cells and are capable of differentiating into ECs and SMCs [6]. However, the method outlined was inefficient and resulted in low yields of ECs and SMCs. To generate adequate quantities of ECs and SMCs with consistent quality, we developed a simple but robust two-dimensional protocol that eliminates embryoid body formation and enriches for a population of vascular progenitor cells (CD34+/CD31+). When these cells are exposed to specific factors, they yield functional ECs and SMCs.

Materials and Methods

Adaptation of hESCs and iPSCs to Feeder-Free Conditions

Pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) were maintained on mouse embryonic feeders (MEFs) as previously described [7] and manually dissected from the MEFs using sterile glass tools under a dissection microscope. Dissected pieces were approximately 100 cells each. Pieces were plated on reduced growth factor Matrigel–coated dishes (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, http://www.bdbiosciences.com) containing 100% MEF-conditioned media. Media were changed every day, and mTeSR1 (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada, http://www.stemcell.com) was introduced daily in a stepwise fashion, increasing by 10% each day (e.g., day 2: 90% conditioned medium/10% mTeSR1; day 3: 80% conditioned medium/20% mTeSR1). Cells had to be passaged during this time. Feeder-free cells were passaged enzymatically with dispase (StemCell Technologies). Cell lines were fully adapted to feeder-free conditions when they were being maintained in 100% mTeSR1 medium.

In Vitro Differentiation of PSCs Into Vascular Cells

hESCs and iPSCs were maintained under feeder-free conditions and cultured in mTeSR1 medium. The differentiation protocol was adapted from Vodyanik et al. [8] and Bai et al. [6, 9]. At day −1, OP9 (mouse bone marrow stromal cells) were plated at a density of 1.5 × 106 cells per 10-cm tissue culture dish coated with 0.2% gelatin. At day 0, feeder-free PSCs were treated with dispase to dissociate colonies into small aggregates. Aggregates were seeded on OP9 cells in OP9 differentiation media consisting of αMEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, http://www.invitrogen.com), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (HyClone, Logan, UT, http://www.hyclone.com), 1% insulin-transferrin-selenium (Invitrogen), and 450 μM monothioglycerol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, http://www.sigmaaldrich.com) and supplemented with 50 ng/ml human bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4) (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ, http://www.peprotech.com), 50 ng/ml human fibroblast growth factor 2 (basic fibroblast growth factor [bFGF]; PeproTech ), and 100 ng/ml human vascular endothelial growth factor (PeproTech). Media were changed every third day. Cells were sorted by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) on day 8 of differentiation. The CD34+/CD31+ vascular progenitors were cultured on fibronectin or collagen IV-coated dishes for further differentiation into ECs and SMCs, respectively, in differentiation medium supplemented with ROCK (rho-associated protein kinase) inhibitor (Sigma-Aldrich ) for 24 hours.

FACS of CD34+/CD31+ Vascular Progenitor Cells

Cells were dissociated with a 50:50 mixture of TrypLE (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, http://www.lifetechnologies.com):Accutase (Innovative Cell Technologies, Inc, San Diego, CA, http://www.innovativecelltech.com). ROCK inhibitor (10 mM) was added, and cells were incubated at 37°C for 5–10 minutes, pipetted to obtain a single-cell suspension, and spun down (300g for 5 minutes) in OP9 medium. Cells were resuspended in a small volume of OP9 medium and placed in the incubator for 30 minutes for recuperation. After the recuperation period, we added 10 ml of FACS buffer (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS] + 0.5% FBS [bovine serum albumin] + 2 mM EDTA) and filtered on a 0.22-µm filter. Cells were spun down again, counted, and resuspended in appropriate volume of buffer for FACS sorting (maximum of 108 cells in 300 µl of FACS buffer). Cells were blocked with mouse IgG (R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN, http://www.rndsystems.com) for 15 minutes and stained for CD34 (clone 8G12), CD31 (clone WM59), VEGFR2 (clone 89106), CD144 (clone 55-7H1), and platelet-derived growth factor β (PDGFRβ) (clone J24-618) (BD Biosciences) for 30 minutes. Stained cells were washed with buffer and centrifuged at 300g for 10 minutes. Pellets were resuspended in 200 μl for gating and 1 ml for sorting. CD31+/CD34+ cells were sorted on a FACSAria (BD Biosciences) and checked for purity. After sorting, cells were plated under conditions for EC differentiation or SMC differentiation.

Generating Vascular ECs From Vascular Progenitors

To generate ECs, the isolated cells were seeded (at day 0) on fibronectin-coated plates with OP9 differentiation medium, supplemented with ROCK inhibitor. On day 1, after sorting, half of the OP9 differentiation medium was removed and replaced with EC medium. Cells were maintained in culture for 7 to 14 days in epidermal growth medium -2 (Lonza, Walkersville, MD, http://www.lonza.com) containing 5% FBS, recombinant human vascular endothelial growth factor, fibroblast growth factor 2, R3- insulin-like growth factor-1, hydrocortisone, ascorbic acid, and heparin supplemented by 100 ng/ml vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Medium was changed every other day. Cells were split and expanded when they reached 90% confluence. Each time cells were split, 1 × 105 cells were used for FACS analysis.

Generating Vascular SMCs From Vascular Progenitors

To generate SMCs, the isolated cells were seeded (at day 0) on collagen IV-coated plates with OP9 differentiation medium supplemented with ROCK inhibitor (Sigma-Aldrich). On day 1 after sorting, half of the OP9 differentiation medium was removed and replaced with smooth muscle cell proliferation medium (SMGS), (Invitrogen). On day 3, the medium was changed to 100% smooth muscle cell proliferation medium. The cells were maintained in culture for 12 to 14 days, and the medium was changed every day. Cells were split and expanded when they reached 90% confluence. Each time cells were split, 1 × 105 were used for FACS analysis. Smooth muscle cells were terminally differentiated to mature SMCs using smooth muscle differentiation medium (SMDS), (Invitrogen) for 10 days [4].

Gene Expression Analysis

For reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction analysis, we extracted total RNA by using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany, http://www.qiagen.com) as previously described [10]. We performed reverse transcription analysis on total RNA (1 µg each) (SuperScript III; Invitrogen). TaqMan probes (Applied Biosystems) and an internal housekeeping gene (HuCyc; Applied Biosystems) were used to determine the relative expression of SMC and EC genes in a 384-well (Applied Biosystems) format.

Immunofluorescence Analysis

Human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) were induced to differentiate in 24-well plates on Matrigel-coated plastic coverslips, washed with PBS, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes at room temperature, washed three times in PBS, permeabilized in cold methanol for 5 minutes, and washed three times in PBS. Coverslips were stored at 4°C until all time points were collected. Nonspecific reactivity was blocked for 1 hour by incubation in 10% goat serum. Then cells were incubated, with primary antibodies generally at 1:100 dilutions, for 1 hour at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. CD31 (R&D Systems), von Willebrand factor (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark, http://www.dako.com), and all other cells were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, U.K., http://www.abcam.com).

Vascular Tube Formation Assay (PSC-Derived ECs)

Matrigel was thawed at 4°C overnight. The following day, 24-well plates were chilled and kept on ice. We added 300 μl of chilled Matrigel (10 mg/ml) per well. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 60 minutes before use. PSC-ECs were grown to 85%–90% confluence and trypsinized. PSC-ECs were resuspended in endothelial cell growth medium at 4 × 105 cells per milliliter; 300 μl of the cell suspension (∼1.2 × 105 cells) in endothelial growth medium was added to each well. The cells were incubated for 18–24 hours before imaging [11].

Coculture Vascular Tube Formation Assay (PSC-Derived ECs and SMCs)

PSC-derived ECs were live stained with PKH26 (Sigma-Aldrich) and PSC-derived SMCs were live stained with PHK67 (Sigma-Aldrich) and combined a day before the vascular tube formation assay. The tube formation assay was completed as above. Both cell types (in combination) were seeded at a density of (4 × 105 cells per milliliter).

Low-Density Lipoprotein Uptake Assay

Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) uptake assays were performed according to manufacturer’s protocol (Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, MI, http://www.caymanchem.com). Essentially, ECs were incubated with LDL-DyLight 549 for 3 hours for Ac-LDL uptake, fixed, and immunostained for LDL receptors.

SMC Contraction Studies

Contractions were induced by treating the cells with 100 μM carbachol (Sigma-Aldrich). Images were recorded every minute for 10 minutes on a Nikon Biostation IM (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan, http://www.nikon.com).

Results

Generation of Vascular Progenitors From hPSCs

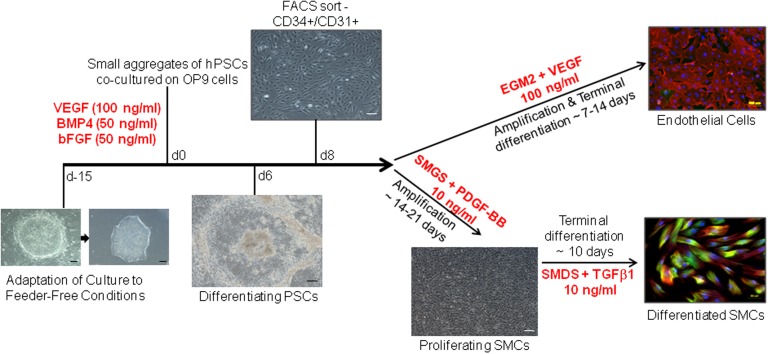

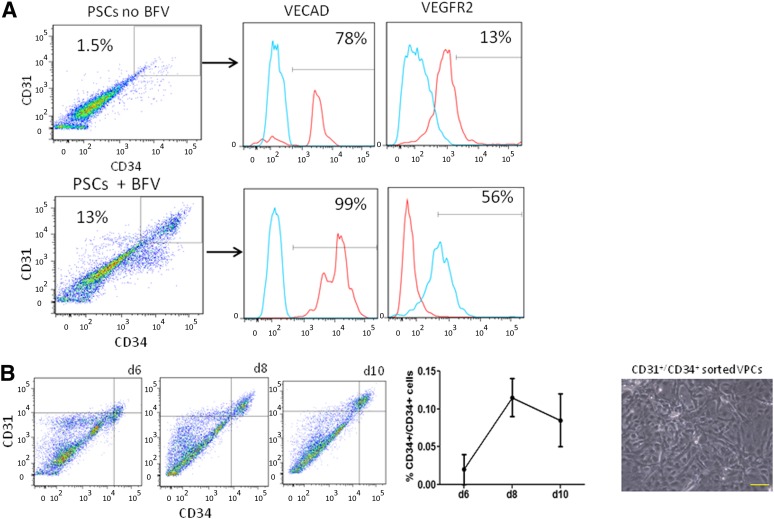

Figure 1 shows a schematic representation of the differentiation protocol of hPSCs into intermediate vascular progenitors and, subsequently, into ECs and SMCs. To initiate differentiation, feeder-free hPSCs (H1 and Wt-iPSC) were seeded as small aggregates on OP9 cells [8, 12] in media supplemented with VEGF, bFGF, and BMP4 (Fig. 2A). A significant increase in CD34+/CD31+ cells from 1% to 10% on day 8 of differentiation was observed (Fig. 2B). A purity sort for CD34+/CD31+ cells showed the population to be greater than 95%. Sorted cells were then plated on either fibronectin or collagen IV for further differentiation to ECs and SMCs, respectively.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of differentiation from hPSCs to mature ECs and SMCs. Fifteen days before differentiation, hPSCs were adapted to feeder-free conditions. On day 0, hPSCs were dissociated and seeded onto OP9 cells in differentiation medium. On day 8, vascular progenitor cells were sorted for the presence of both CD31 and CD34. Vascular progenitors were then plated and amplified under growth conditions for vascular ECs or SMCs. Abbreviations: bFGF, basic fibroblast growth factor; BMP4, bone morphogenetic protein 4; d, day; EC, endothelial cell; EGM2, epidermal growth medium-2; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; hPSC, human pluripotent stem cell; PDGF-BB, platelet-derived growth factor-BB; SMC, smooth muscle cell; SMDS, smooth muscle differentiation supplement; SMGS, smooth muscle growth supplement; TGFβ1, transforming growth factor β1; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Figure 2.

Optimization of growth factors with OP9 coculture. (A): Addition of BFV (BMP4, bFGF, and VEGF) growth factor cocktail to OP9 coculture conditions increased the yield of vascular progenitors approximately 10-fold. (B): Time course quantifying highest percentage of CD34+/CD31+ cells on differentiation day 8 and phase contrast images of sorted cells. Abbreviations: bFGF, basic fibroblast growth factor; BFV, BMP4 + bFGF + VEGF; BMP4, bone morphogenetic protein 4; d, day; PSC, pluripotent stem cell; VECAD, vascular endothelial cadherin; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

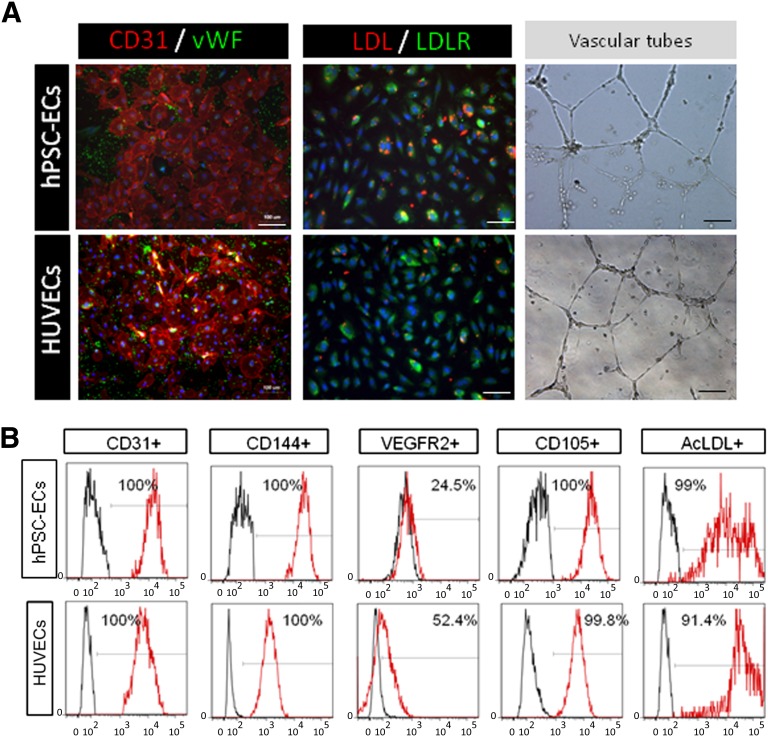

Generation and Characterization of ECs From Volume-Packed Cells

When cultured in endothelial differentiation medium supplemented with EGM2 and VEGF, the majority of cells adhered to fibronectin-coated plates and expressed endothelial markers CD31 and von Willebrand factor (Fig. 3A). The adherent cells took up DiI-acetylated low-density lipoprotein and rapidly formed a vascular network-like structure when placed in Matrigel (Fig. 3A). The cells also expressed CD144, VEGRF2, and CD105 (endoglin), and they incorporated acetylated low-density lipoprotein (Fig. 3B). These data indicate that CD34+CD31+ cells were able to differentiate into pure and functional endothelial cells [11] when cultured in endothelial growth medium. In our hands, the hPSC-ECs continued to proliferate for five to six passages in culture with a split ratio of 1:3. We observed that beyond this passage, the hPSC-ECs needed to be resorted to maintain purity and could be expanded up to 15 passages.

Figure 3.

Characterization of endothelial cells. (A): Comparison of differentiated endothelial cells and HUVECs, both positive for CD31, vWF, and DiI-AcLDL uptake and able to form vascular tubes in vitro. Scale bars = 10 and 100 µm. (B): Profile of derived endothelial cells (day 15 of differentiation) and staining for the presence of EC markers CD31, CD144, VEGFR2, CD105, and AcLDL in comparison with HUVEC line. Abbreviations: AcLDL, acetylated low-density lipoprotein; EC, endothelial cell; hPSC, human pluripotent stem cells; HUVEC, human umbilical vein endothelial cell; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; VEGFR, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor; vWF, von Willebrand factor.

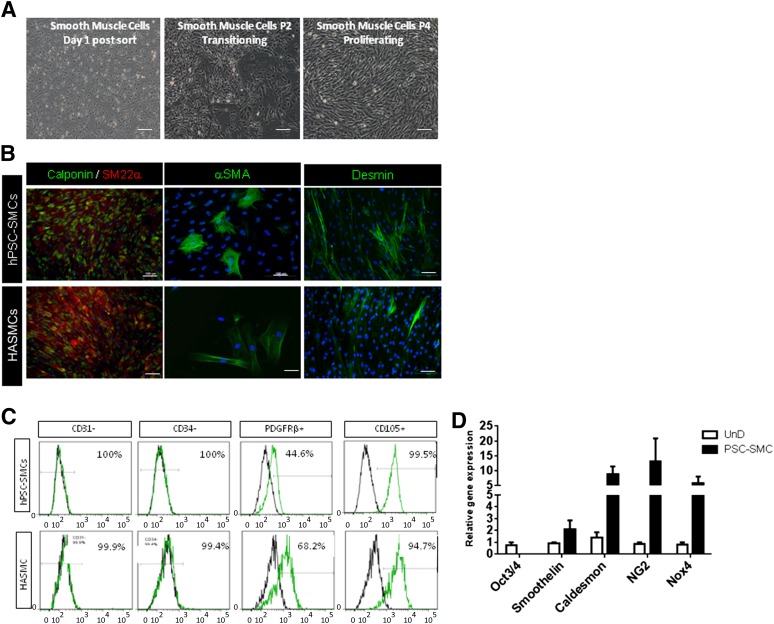

Generation and Characterization of Smooth Muscle Cells From Volume-Packed Cells

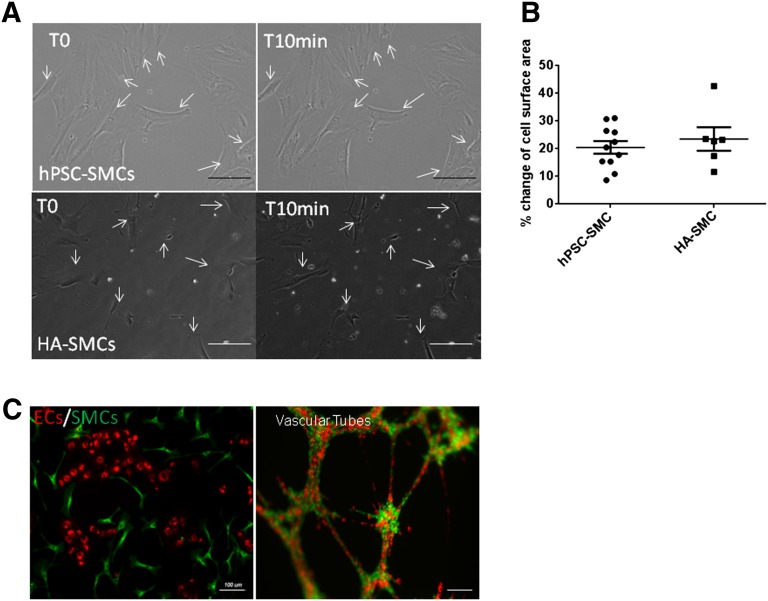

In contrast, a complete morphology change was observed after 24–36 hours of seeding CD34+CD31+ cells in SMC proliferation media supplemented with PDGFB (Fig. 4A). The cells flattened and, soon after, acquired typical spindle shape-fibroblast like morphology. Immunofluorescent staining revealed robust expression of desmin, αSMC, calponin, and SM22α in these cells (Fig. 4B). FACS analysis showed a marker profile comparable to that of the control human aortic SMC line, including a complete absence of CD31 and CD34 expression (Fig. 4C). As shown in Figure 4D, the proliferating SMCs showed the presence of smoothelin, caldesmon, NG2, and Nox4 transcripts and an absence of Oct3/4 transcripts. Smoothelin is a structural protein that colocalizes with α-SMA in the cytoskeleton and is a specific marker of contractile SMCs [13]. It is of major interest here because it is the only marker that differentiates between SMCs and myofibroblasts [14]. In our hands, the hPSC-SMCs continued to proliferate for seven to eight passages in culture with a split ratio of 1:3. On exposure to SMDS and transforming growth factor β1, the proliferating SMCs were terminally differentiated into mature, functional SMCs. To assess SMC contractile potential, the cells were exposed to carbachol. Time-lapse microscopy (supplemental online Movie 1) showed that our SMCs contracted in a tonic fashion during the 10 minutes of carbachol treatment, consistent with the sustained contraction usually manifested by vascular SMCs (human aortic SMCs) (supplemental online Movie 2) in controlling vessel tone (Fig. 5A). More than 50% of cells contracted on carbachol treatment and exhibited a 15%–20% change in cell surface area (n = 20) (Fig. 5B).

Figure 4.

Characterization of smooth muscle cells. (A): Morphology changes observed during SMC differentiation after sorting (day 1), transitioning (passage 2), and proliferating (passage 4). (B): Immunocytochemistry of the SMC markers desmin, αSMA, calponin, and SM22α in comparison with the HASMC line. (C): Fluorescence-activated cell sorting profile indicating the absence of CD31 and CD34 and similar expression of PDGFRβ and endoglin (CD105) to HASMCs after 14 days of SMC differentiation conditions. (D): Gene expression of SMC markers in derived SMCs versus undifferentiated hPSCs. Scale bars = 10 and 100 µm. Abbreviations: HASMC, human aortic smooth muscle cell; hPSC, human pluripotent stem cell; PDGFRβ, platelet-derived growth factor β; SMC, smooth muscle cell.

Figure 5.

Functional characterization of derived SMCs and ECs. (A): SMCs cultured with 100 μM carbachol were functionally able to contract. Prior treatment with atropine inhibited contraction of SMCs. (B): hPSC-SMCs and HA SMCs showed a 15%–20% change in surface area after contraction. (C): Coculturing of terminally differentiated SMCs and ECs formed vascular tubes in vitro. Abbreviations: EC, endothelial cell; HA, human aortic; hPSC, human pluripotent stem cell; SMC, smooth muscle cell.

Functional Characterization of hPSC-Derived SMCs and ECs

To evaluate functional interactions between the two cell types, we examined whether the hPSC-derived SMCs and ECs could contribute to vessel formation in vitro. hPSC SMCs and ECs were labeled with different fluorochrome dyes and were cocultured in a Matrigel tube formation assay. As shown in Figure 5C, a mixture of these cells generated robust three-dimensional networks of vasculature-like structures that appear to recapitulate in vivo EC and SMC interactions. Similar results were obtained when ECs and SMCs were derived from iPSCs generated from a control fibroblast line (supplemental online Fig. 1).

Discussion

Production of human ESC/iPSC-derived ECs and SMCs might provide materials for modulating revascularization to treat ischemic diseases such as myocardial infarction, chronic ischemic cardiomyopathy, stroke, and critical limb ischemia [15, 16] and will undoubtedly have many applications in basic science. Previous strategies to produce these cells have yielded mixed outcomes (supplemental online Table 1); moreover, replacement of endothelial cells alone is inadequate [1, 2]. Vascular smooth muscle cells are indispensable for vascular homeostasis and to mediate hemodynamics. Hence, endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells are necessary for the formation of a functional vasculature.

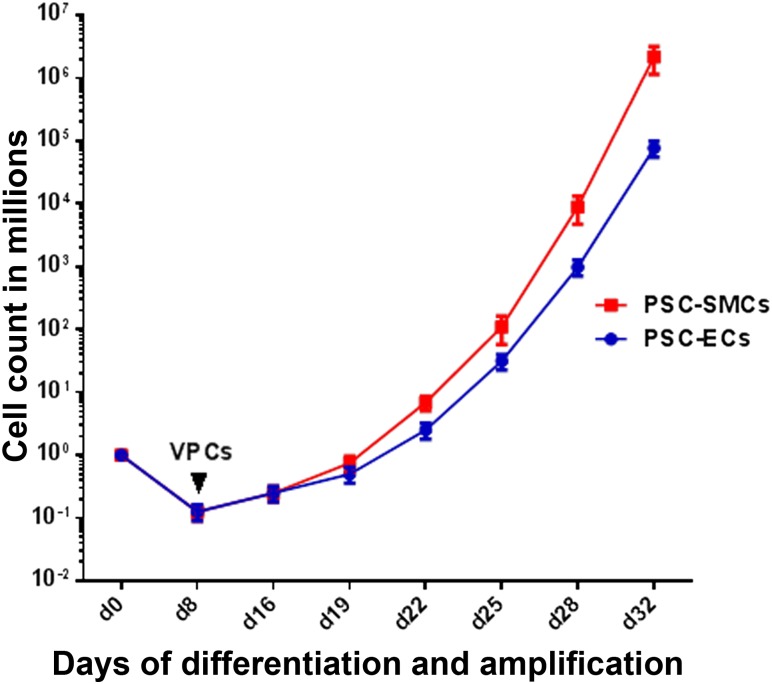

Here, we demonstrated an efficient and robust protocol for simultaneous generation of ECs and SMCs from hPSCs via a common vascular progenitor population. In the past decade, the focus has been on using three-dimensional embryoid bodies [17] to derive ECs. However, this process is inefficient and results in low yields of ECs [18] and SMCs. Obtaining a sufficient number of differentiated cells in any given specific lineage is a severe limitation to applications in stem cell biology and regenerative medicine. Our two-step, two-dimensional culture system generated a common vascular progenitor population with an efficiency of 10%–20% of the total culture, with a 10- to 100-fold increase of efficiency over previous methods of differentiation [6, 19](supplemental online Table 1). Starting from approximately 1 × 106 PSCs, 2 × 105 vascular progenitors were obtained. Furthermore, we were able to expand the intermediate population more than a billionfold (1.5 × 109 cells) (Fig. 6) and, in the second phase of differentiation, 100% of these cells were able to differentiate and mature into either endothelial cells or smooth muscle cells, both of which were functional in vitro. Thus, this differentiation system is scalable to produce large populations of ECs and SMCs, which may be able to satisfy the immense demand for cell therapy in a clinical setting. Moreover, applications of SMCs in human health include applications in uterine abnormalities, urinary bladder wall degeneration [20], urinary incontinence, erectile dysfunction, esophageal dysfunction, asthma, and hollow organ [21] applications.

Figure 6.

Cell count curve depicting differentiation of PSCs to VPCs and subsequent expansion of PSC-SMCs and PSC-ECs. Starting from 1 million PSCs, 10%–20% of VPCs (sorted on day 8), were expanded more than 1 billionfold over approximately 30 days of amplification. Abbreviations: EC, endothelial cell; PSC, pluripotent stem cell; SMC, smooth muscle cell; VPC, volume-packed cell.

Conclusion

The regeneration of vascular tissue requires synergistic association between endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells. Therefore, it is of great importance to generate both cell types simultaneously. We demonstrated that it is possible to get highly scalable, consistent quality quantities of ECs and SMCs via a common vascular progenitor. These concurrently generated ECs and SMCs may provide a renewable resource for potential clinical applications in the field of vascular regeneration and repair.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributed equally as first authors.

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Reijo Pera laboratory for technical assistance and discussions. This work was supported by the Stanford Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine, CIRM (TR3-05569 and RL1-00662) and the NIH (Grants U01-HL100397 and U01-HL099776).

Author Contributions

M.M.: design and performance of experiments, data analysis; E.K.A.: design and performance of experiments, data analysis, manuscript writing of first draft; S.M.P.: performance of experiments, data analysis, manuscript writing; M.T.L., J.P.C., and B.C.: assistance in experimental design, data analysis, manuscript editing; R.A.R.P.: design of experiments, provision of resources, interpretation of results, assistance in manuscript writing and editing.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

M.T.L. is a compensated consultant and has uncompensated stock options with Neodyne Biosciences, Inc.

References

- 1.Hellström M, Gerhardt H, Kalén M, et al. Lack of pericytes leads to endothelial hyperplasia and abnormal vascular morphogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:543–553. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.3.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindahl P, Johansson BR, Levéen P, et al. Pericyte loss and microaneurysm formation in PDGF-B-deficient mice. Science. 1997;277:242–245. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5323.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jain RK. Molecular regulation of vessel maturation. Nat Med. 2003;9:685–693. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheung C, Bernardo AS, Trotter MW, et al. Generation of human vascular smooth muscle subtypes provides insight into embryological origin-dependent disease susceptibility. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:165–173. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mikawa T, Gourdie RG. Pericardial mesoderm generates a population of coronary smooth muscle cells migrating into the heart along with ingrowth of the epicardial organ. Dev Biol. 1996;174:221–232. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bai H, Gao Y, Arzigian M, et al. BMP4 regulates vascular progenitor development in human embryonic stem cells through a Smad-dependent pathway. J Cell Biochem. 2010;109:363–374. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wen Y, Wani P, Zhou L, et al. Reprogramming of fibroblasts from older women with pelvic floor disorders alters cellular behavior associated with donor age. Stem Cells Translational Medicine. 2013;2:118–128. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2012-0092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vodyanik MA, Bork JA, Thomson JA, et al. Human embryonic stem cell-derived CD34+ cells: Efficient production in the coculture with OP9 stromal cells and analysis of lymphohematopoietic potential. Blood. 2005;105:617–626. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bai H, Wang ZZ. Directing human embryonic stem cells to generate vascular progenitor cells. Gene Ther. 2007;15:89–95. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3303005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Medrano JV, Ramathal C, Nguyen HN, et al. Divergent RNA-binding proteins, DAZL and VASA, induce meiotic progression in human germ cells derived in vitro. Stem Cells. 2012;30:441–451. doi: 10.1002/stem.1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong WT, Huang NF, Botham CM, et al. Endothelial cells derived from nuclear reprogramming. Circ Res. 2012;111:1363–1375. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.247213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vodyanik MA, Thomson JA, Slukvin II. Leukosialin (CD43) defines hematopoietic progenitors in human embryonic stem cell differentiation cultures. Blood. 2006;108:2095–2105. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-003327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christen T, Verin V, Bochaton-Piallat M, et al. Mechanisms of neointima formation and remodeling in the porcine coronary artery. Circulation. 2001;103:882–888. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.6.882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maeng M, Mertz H, Nielsen S, et al. Adventitial myofibroblasts play no major role in neointima formation after angioplasty. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2003;37:34–42. doi: 10.1080/14017430310007018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheung C, Sinha S. Human embryonic stem cell-derived vascular smooth muscle cells in therapeutic neovascularisation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;51:651–664. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raval Z, Losordo DW. Cell therapy of peripheral arterial disease: From experimental findings to clinical trials. Circ Res. 2013;112:1288–1302. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.300565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferreira LS, Gerecht S, Shieh HF, et al. Vascular progenitor cells isolated from human embryonic stem cells give rise to endothelial and smooth muscle like cells and form vascular networks in vivo. Circ Res. 2007;101:286–294. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.150201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zambidis ET, Park TS, Yu W, et al. Expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme (CD143) identifies and regulates primitive hemangioblasts derived from human pluripotent stem cells. Blood. 2008;112:3601–3614. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-144766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hill KL, Obrtlikova P, Alvarez DF, King JA, Keirstead SA, et al. Human embryonic stem cell-derived vascular progenitor cells capable of endothelial and smooth muscle cell function. Exp Hematol. 2010;38:246–257. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharma AK, Bury MI, Fuller NJ, et al. Cotransplantation with specific populations of spina bifida bone marrow stem/progenitor cells enhances urinary bladder regeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:4003–4008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220764110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huber A, Badylak SF. Phenotypic changes in cultured smooth muscle cells: Limitation or opportunity for tissue engineering of hollow organs? J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2012;6:505–511. doi: 10.1002/term.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.