Abstract

Objective

This study investigates the association between bereavement and the mortality of a surviving spouse among Amish couples. We hypothesised that the bereavement effect would be relatively small in the Amish due to the unusually cohesive social structure of the Amish that might attenuate the loss of spousal support.

Design

Population-based cohort study.

Setting

The USA.

Participants

10 892 Amish couples born during 1725–1900 located in Pennsylvania, Ohio and Indiana. All the participants are deceased.

Outcome measures

The survival time is ‘age’; event is ‘death’. Hazard ratios (HRs) of widowed individuals with respect to gender, age at widowhood, remarriage, the number of surviving children and time since bereavement.

Results

We observed HRs for widowhood ranging from 1.06 to 1.26 over the study period (nearly all differences significant at p<0.05). Mortality risks tended to be higher in men than in women and in younger compared with older bereaved spouses. There were significantly increased mortality risks in widows and widowers who did not remarry. We observed a higher number of surviving children to be associated with increased mortality in men and women. Mortality risk following bereavement was higher in the first 6 months among men and women.

Conclusions

We conclude that bereavement effects remain apparent even in this socially cohesive Amish community. Remarriage is associated with a significant decrease in the mortality risk among Amish individuals. Contrary to results from previous studies, an increase in the number of surviving children was associated with decreased survival rate.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Geriatric Medicine, Mental Health, Public Health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Owing to the availability of remarriage status of the surviving spouses, we could reproduce and quantify the decreased bereavement effect associated with remarriage.

Owing to the unavailability of data on causes of death, it was not possible to determine the relationship between differential measures of social support and certain causes of death.

The number of surviving children was simplified to be a time-independent covariate although it may change between the death of the first parent and the death of the second parent.

Introduction

It has been consistently established that widowed individuals exhibit an increased mortality compared with married individuals.1–4 This excess mortality risk, referred to as the ‘bereavement effect,’ is strongest in the first few years following widowhood, among men who outlive their wives and among younger widows/widowers.2 5 Factors proposed to explain this phenomenon include the acute grief and stress of bereavement, shared environmental risk factors between spouses, marital selection, economic hardship and loss of social support.6 7

These influences are difficult to isolate and independently assess. Several studies have shown that a larger social network size and a greater level of social support are generally associated with lower rates of mortality and morbidity.4 In a study based on the Utah Population Database, mortality risk among widowers decreased with membership in the Church of Latter Day Saints (LDS, a.k.a. Mormon Church) and with increasing numbers of children. These factors were interpreted as proxies for social support.8 In addition, a study in Washington County, Maryland, indicated that living alone was a risk factor for increased mortality in widowed populations.9 Loss of social support following the death of a spouse is generally more profound in widowers than in widows, but there is currently no empirical evidence that this difference mediates the higher mortality consistently observed among widowed husbands compared with widowed wives.10 11

The Amish maintain a cultural identity distinct from mainstream American culture that is characterised by traditional dress, a plain lifestyle and non-adoption of modern technology (eg, electricity, cars and telephones), German dialect, separate school system and ultra-conservative Anabaptist religious practices. A central tenet of Amish culture throughout its history in the USA has been social cohesiveness with emphasis on family and community. Members of this tight-knit society have extraordinary social support from cradle to grave, including community financing of medical costs and support during times of need. The community financing of medical costs became increasingly formalised during the 20th century to the point where it is now a formal system of self-insurance called ‘Amish Aid’.

To gain a different perspective on potential influences of social support on bereavement, we assessed the bereavement effect in an Amish population, whose culture is characterised by its core beliefs in community and social cohesion. Examples of the strong degree of social support within the Amish include community-managed health insurance, community ties through membership in the church, and the sharing of ultraconservative cultural beliefs and lifestyles.12 We reasoned that the high level of social support in the Amish population might mitigate the bereavement effect. Previous studies used covariates such as education (homogeneous in the Amish),12 health habits, remarriage, church visits, neighbourhood interaction and household size to study the relationship between bereavement and social support.4 8 13

We estimated bereavement effects in widows and widowers separately and further assessed the mortality risks as a function of age at widowhood and time since bereavement (TSB).2 8 We used Cox proportional hazard (CPH) models to analyse the association of bereavement and mortality of widowed husbands and wives. We considered remarriage and the number of surviving children as additional potential modifiers of the bereavement effect.

Material and methods

Data source

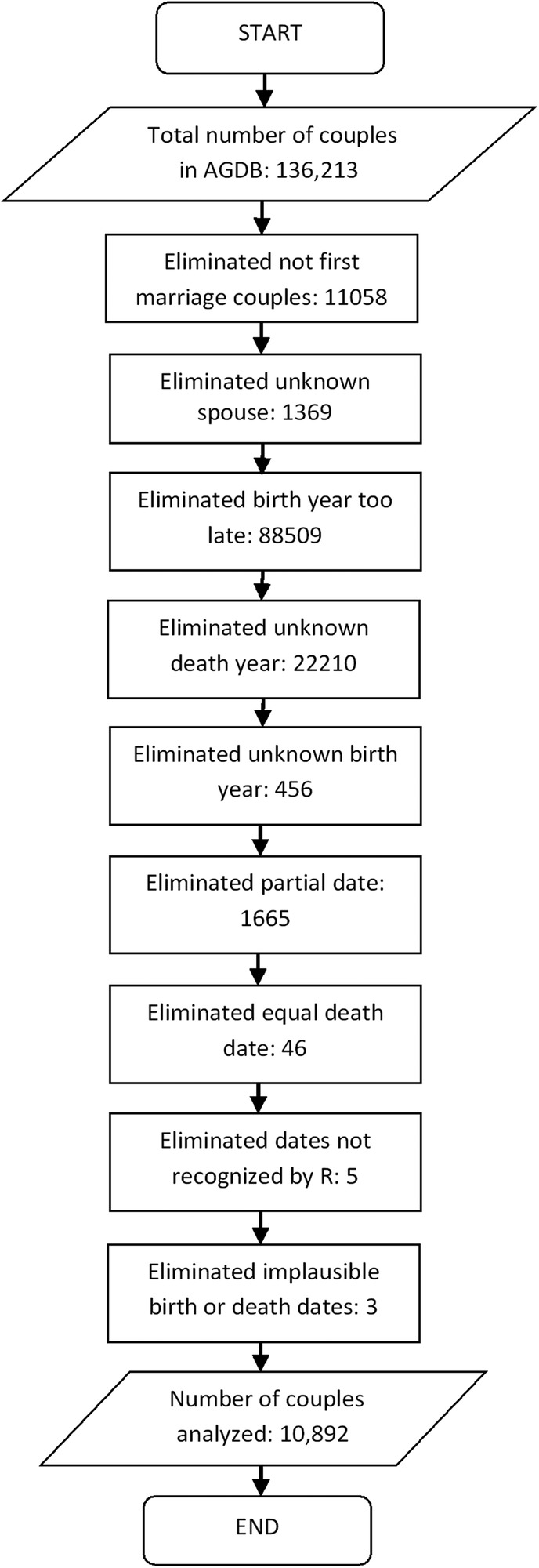

The Anabaptist Genealogy Database (AGDB) V.5 was used to study the effect of bereavement on the Amish population.14 15 The AGDB is a computerised genealogy database of the Amish and some Mennonite populations, last updated in 2010. This database includes information about the family relationships and the birth, marriage and death dates of children of Amish individuals from North America, mostly located in Pennsylvania, Ohio and Indiana. The ‘individual table’ of AGDB contains information about 539 822 individuals. The ‘relationship table’ includes information about 136 213 Amish couples. An individual who is married multiple times participates in multiple relationship table entries. There are 1369 relationship entries among the 136 213 entries concerning children for whom one or both biological parents are unknown (figure 1).

Figure 1.

A flow diagram representing all the steps performed for filtering 10 892 couples from a total of 136 213 couples available in Anabaptist Genealogy Database (AGDB). In the flow diagram, each couple is counted as excluded only once, even if multiple exclusion criteria apply. ‘Unknown spouse’ refers to entries in the AGDB relationship table in which at least one parent is unknown; almost all of these entries are for adopted children for whom at least one of the biological parents is unknown. As AGDB is used primarily in genetic studies (unlike this study), the distinction between biological and adoptive relationships is stored. ‘Birth year too late’ means that the birth year of the husband or wife is known and is >1901. ‘Dates not recognised by R’ are invalid dates such as the 31 June, which got into AGDB due to errors in the original sources. ‘Implausible birth or death dates’ refer to a few individuals who are shown as married but have lifespans of less than 10 years likely due to typos in the birth year in the original sources.

The Amish people rarely give birth out of wedlock, and a vast majority of the mating samples we used are documented as marriages in the three original sources from which AGDB is derived. However, there is less availability of marriage dates than birth dates; we did not wish to exclude couples with missing marriage dates. For this study, we included couples in which both spouses met four conditions: (1) they were born prior to 1 January 1901; (2) their birth and death dates were recorded; (3) they were in their first marriage and (4) they did not die on the same day. Constraint (4) excludes couples who may have died from a shared disaster (eg, accident). A total of 10 892 couples met the inclusion criteria. The oldest person included was born on 14 February 1725, and the youngest on 30 December 1900. See figure 1 for how the exclusion criteria were applied.

Our dataset included 10 892 couples with information on their dates of birth, dates of death, the number of surviving children, family IDs and remarriage status after widowhood. For some analyses, these couples were first partitioned into three cohorts based on the husband’s birth year (prior to 1850 and 1850–1875) and based on husband's and wife's birth year (1876–1900) and sex. For the TSB analyses, we did not partition into cohorts because the number of widow(er)s who died within 6 months after being bereaved is small (N=291). The characteristics of these couples are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 10 892 spouse pairs according to birth cohort of husband

| Cohorts | Pre-1850 | 1850–1875 | 1876–1900 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of couples | 3711 | 3210 | 3971 |

| Number (%) of wives out-surviving their husband | 2043 (55.0) | 1661 (51.7) | 2043 (51.4) |

| Number (%) of husbands out-surviving their wife | 1668 (45.0) | 1549 (48.3) | 1928 (48.2) |

| Mean husband age at widowhood | 63.0 | 59.8 | 62.2 |

| Mean wife age at widowhood | 62.0 | 62.8 | 66.9 |

| Mean widowed husband survival in years | 14.4 | 18.3 | 18.4 |

| Mean widowed wife survival in years | 15.3 | 16.0 | 16.6 |

| Mean husband age at death | 71.1 | 72.0 | 74.6 |

| Mean wife age at death | 69.6 | 68.5 | 72.6 |

| Mean age difference husband-wife | 3.4 | 2.8 | 2.0 |

| Mean number of children | 5.4 | 5.3 | 5.3 |

| Number (%) of widowed husbands remarried | 238 (14.2) | 404 (26.0) | 648 (33.6) |

| Number (%) of widowed wives remarried | 58 (2.8) | 140 (8.4) | 180 (8.8) |

Statistical analyses

Similar to several past analyses,2 8 13 16 we used the CPH model where the response variable or survival time is ‘age at death’ and the event is ‘death’. The model is used to study the association of widowhood and mortality rates in the surviving spouse, while adjusting for covariates such as education, health habits, age in years, the number of children and remarriage. In some of our analyses, we adjusted for remarriage and the number of children as covariates; we did not adjust for education or health habits. Husbands and wives were always analysed separately.

The main covariate, widowhood, was monitored as a time-dependent covariate, by assigning a value of 1 for each time period the individual was widowed, and 0 otherwise. The remarriage covariate was also a time-dependent covariate, by assigning a value 1 for the widowed period if the individual remarried, and 0 otherwise. The number of surviving children was a time-independent covariate and counted at the beginning of the widowhood period of the surviving spouse. The covariate was divided into three categories as follows: 0=number of surviving children is ≤2, 1=number of surviving children is between 3 and 6 and 2=number of surviving children is >6. The categories ≤2 children, 3–6 children and >6 children are separate. These boundaries were chosen to ensure categories that were roughly balanced in size. To evaluate any possible bias by counting the number of surviving children at the death of the first spouse, we also estimated how many couples changed categories between the death of the first spouse and the death of the second spouse due to death of one or more children during the widowhood period.

Survival analyses were performed using the R programming environment.17 All estimates and CIs were obtained using the coxph function available in the survival package.

Representation of survival data for CPH analysis

We show below examples of how we represented the survival data for CPH analysis using a time modelling approach. To represent the survival data columns, the standard approach is to convert the couple's demographic information, date of death, date of birth, remarriage and the number of surviving children in columns representing start time, stop time, event status and all of the included covariates (widowhood, remarriage and the number of surviving children).18 19 Here (start, stop) is an interval of risk, open on the left and closed on the right; the event column is set to 1 if the participant had an event (death) at time stop, and is 0 otherwise. To illustrate the subtleties, we consider a hypothetical example of three wives (ID1, ID2 and ID3) from the cohort 1850 to 1875.

ID1: born on 1 January 1860; widowed on 1 January 1907 at age 47; got remarried; the number of surviving children=3 and eventually died on 1 January 1923 at age 63.

ID2: born on 9 January 1870; widowed on 9 January 1930 at age 60; never got remarried; the number of surviving children=6 and died on 9 January 1955 at age 85.

ID3: born on 3 January 1871; never widowed and never remarried; the number of surviving children=4 and died on 4 January 1930 at age 59.

The data used for the CPH considering widowhood as a single time-dependent covariate is presented in table 2. The following model was used to estimate the association between widowhood and mortality.

Table 2.

Data structure for Cox Proportional Hazard model that does not estimate the effect for different ages, but instead estimates only widowed versus non-widowed

| ID | Start | Stop | Event | W | R | C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 47 (age at widowhood) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 1 | 47 | 63 (age at death) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| 2 | 0 | 60 (age at widowhood) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| 2 | 60 | 85 (age at death) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| 3 | 0 | 59 (age at death) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

C, number of surviving children; R, remarriage.

This model can be run with additional covariates and results that adjust for the ability to remarry and for the number of surviving children presented.

Timing of widowhood

The above model considers widowhood as a single time-dependent covariate, evaluating the association between mortality and being widowed. One can further ask whether that association varies over the life course by considering the impact of age at widowhood on mortality. We addressed this issue following the approach of Mineau et al8 by adding terms for age at widowhood into the model as covariates (<45, 45–54, 55–64, 65–74 and >75) to allow the HR to vary according to age at widowhood (see table 3). These terms were included in the model as time-dependent dummy variables, created to represent the widowhood experience of each individual across the five age windows spanning the individual's age: W<45, W45–54, W55–64, W65–74 and W75+. Furthermore, we also addressed the impact of remarriage and the number of surviving children on the mortality of Amish individuals.

Table 3.

Data structure for Cox Proportional Hazard model that estimates the association between widowhood at given ages and mortality

| ID | Start | Stop | Event | W<45 | W45–54 | W55–64 | W65–74 | W75+ | R | C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 47 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 1 | 47 | 63 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| 2 | 0 | 60 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| 2 | 60 | 85 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| 3 | 0 | 59 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

C, number of surviving children; R, remarriage.

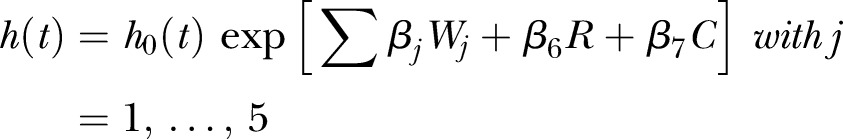

The following model can be used to estimate the association between each of the five dummy variables and mortality:

|

where W1,…,W5 dummy variables are associated with W<45, W45–54, W55–64, W65–74, W75+ columns provided in table 3.

Time since bereavement

Next, we evaluated the association between mortality and TSB or widowhood. We followed the approach of Schaefer et al2 by considering the following TSB ranges: 0–6, 7–12, 13–24, 25–36, 37–48, 49–60 and >60 months. This approach allowed us to estimate HR according to TSB (see table 4). The columns TSB0–6, TSB7–12, etc in table 4 are time-dependent covariates that change with the survival time associated with widowed husbands and wives. We did not account for remarriage in this analysis because of missing remarriage dates.

Table 4.

Data structure for Cox Proportional Hazard model that estimates the association between widowhood with respect to time since bereavement and mortality

| ID | Start | Stop | Event | TSB0–6 | TSB7–12 | TSB13–24 | TSB25–36 | TSB37–48 | TSB49–60 | TSB>60 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID1 | 0 | 47 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ID1 | 47 | 47.5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ID1 | 47.5 | 48 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ID1 | 48 | 49 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ID1 | 49 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ID1 | 50 | 51 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| ID1 | 51 | 52 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| ID1 | 52 | 63 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| ID2 | 0 | 60 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ID2 | 60 | 60.5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ID2 | 60.5 | 61 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ID2 | 61 | 62 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ID2 | 62 | 63 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ID2 | 63 | 64 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| ID2 | 64 | 65 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| ID2 | 65 | 85 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| ID3 | 0 | 59 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Start and stop columns are in years and TSB columns are in months.

TSB, time since bereavement.

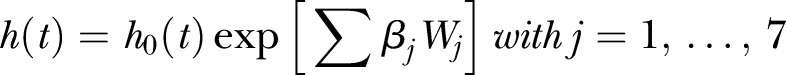

The following model was used to study the association between mortality and TSB:

|

where W1,…,W7 dummy variables are associated with the TSB0–6, TSB7–12, TSB13–24, TSB25–36, TSB37–48, TSB49–60 and TSB>60 columns provided in table 4.

Results

We initially partitioned the 10 892 couples from AGDB into three cohorts ranging in size from 3210 (husband's birth year 1850–1875) to 3971 (husband's birth year 1876–1900). Wives were more likely to die after their husbands in all three cohorts while husbands had a higher mean age at death than their wives. The average age differences between the husbands and wives for all cohorts are shown in table 1. The number of remarried wives was far smaller than the number of remarried husbands (n=1290 widowed husbands vs 378 widowed wives). The number and proportion of remarried husbands and wives were increased in the more contemporary cohorts (see table 1). In contrast to other populations from the 19th and early 20th centuries,4 the majority of widowed husbands did not remarry, making it interesting to study the effect of remarriage in the Amish population.

HRs

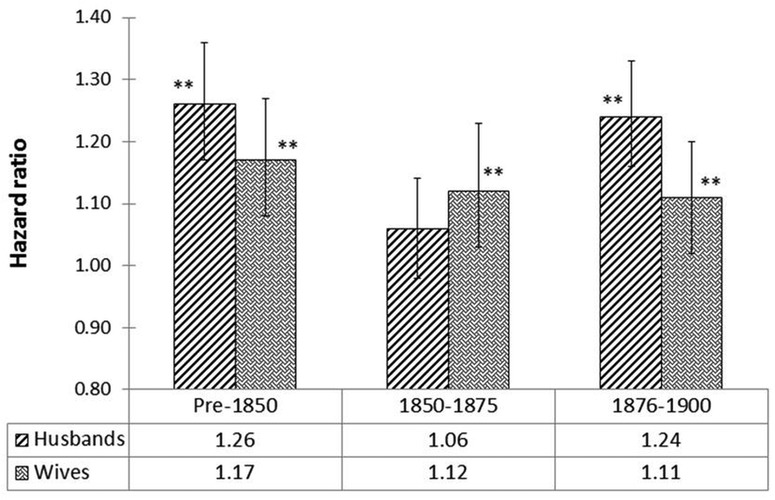

The overall HRs, and their 95% CIs, associated with widowhood are displayed in figure 2 according to birth cohort. The significance of these HRs is indicated with the help of p values (*p<0.05 and **p<0.001) on the top of each block in figure 2. These HRs were estimated using the CPH model and design provided in table 2. As expected, widowhood was associated with an increased mortality for husbands and wives following the death of their spouse, with HRs ranging from 1.06 to 1.26 (all HRs significantly greater than 1 except for widowed husbands in cohort 1850–1875). The impact of widowhood was disproportionately greater on surviving husbands than on surviving wives in the pre-1850 and 1876–1900 cohorts, although there was little difference in mortality between widowed husbands versus wives in the 1850–1875. There was no clear trend showing that the HRs changed across cohorts in either surviving husbands or wives.

Figure 2.

HRs of widowed husbands and wives versus their married counterparts (design provided in table 2); * and ** on top of the blocks representing the significance of HRs with p<0.05 and p<0.001, respectively.

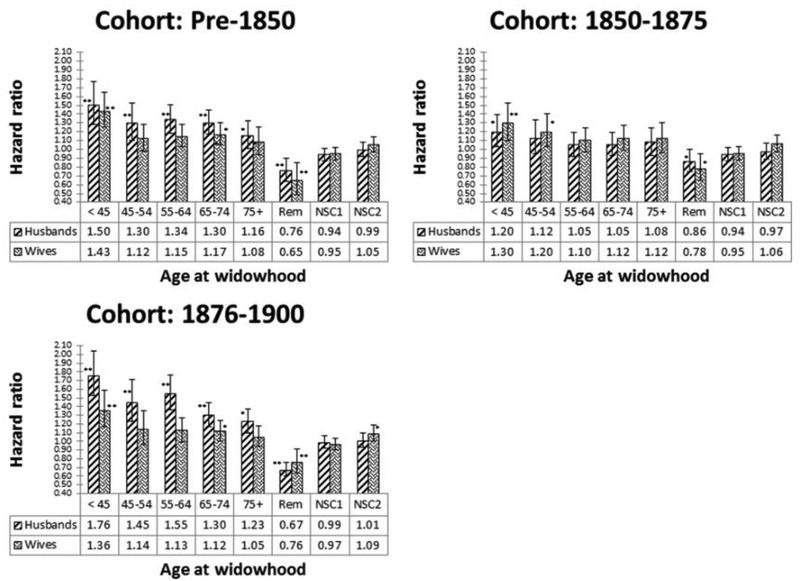

Figure 3 shows the HRs along with 95% CIs, and range of p values for the model in which age at widowhood is accounted for (design model in table 3). These results reveal markedly higher bereavement effects in each age at widowhood group compared with the results shown in figure 2, consistent with the notion that the bereavement effect may be diminished over time and most pronounced in the years proximal to the death of the spouse.2 5 20 21 In nearly all age at widowhood categories, the bereavement effect is stronger in widowed husbands than in widowed wives.

Figure 3.

HRs of widowed husbands and wives versus their married counterparts according to age at widowhood (design provided in table 3); NSC1: Number of Surviving Children (3–6 vs ≤2); NSC2: Number of Surviving Children (>6 vs ≤2); * and ** on top of the blocks representing the significance of HRs with p<0.05 and p<0.001, respectively.

The number of children surviving when the first spouse died (with 2 pairwise comparisons 3–6 vs ≤2; >6 vs ≤2) was included as a time-independent covariate in the models whose results are shown in figure 3. In general, there was a very weak association between the number of surviving children and mortality in husbands and wives. Contrary to our expectations and a prior study,8 in each case, the higher number of surviving children was not significantly associated with lower mortality in husbands and wives (see figure 3). Furthermore, the results in figure 3 show that the effect of bereavement decreases if the Amish individual remarries.

There are two potential sources of bias in analyses involving the number of surviving children covariate. Couples in which one spouse died at age <50 are likely not to have as many children as couples in which both parents survived to at least age 50. To quantify this bias, we repeated the analysis in figure 3 by excluding all the couples who got widowed before age 50 (data not shown). The results show that there is no significant change in the HRs versus figure 3. The maximum change for any of the HRs related to the number of surviving children was 0.03 (data not shown).

On the other end of the age spectrum, there is a potential source of bias as more children may die, the longer the surviving parent lives. As the number of children was divided into three categories ≤2, 3–6 and >6, any possible bias could arise only when the death of a child shifted the number of surviving children from a higher category to a lower category. Over all couples, the number of widows or widowers whose number of surviving children changed to a lower category from the date of widowhood to the date of death was only 298 (<3% of all couples).

When the analyses corresponding to figure 3 were repeated excluding these 298 couples, the HRs were essentially unchanged. The maximum change was 0.04; sometimes the HR increased slightly and sometimes it decreased slightly (data not shown).

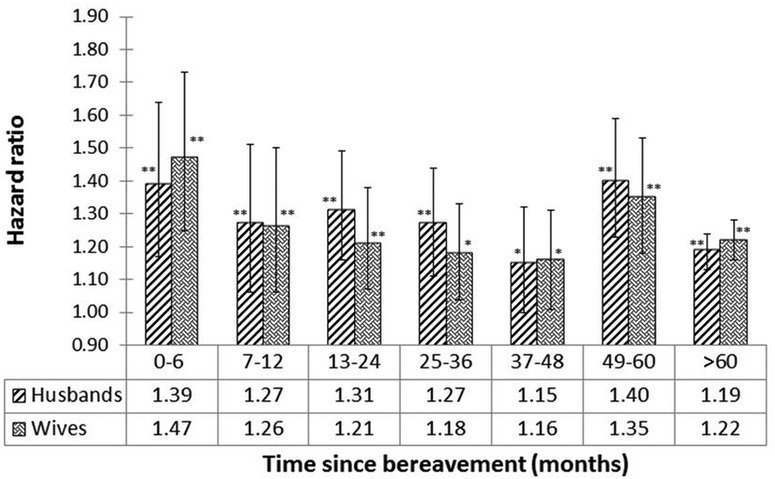

HRs and 95% CIs for the TSB analysis are shown in figure 4. The significant p values are indicated in figure 4. These results were obtained using the CPH model and the design is defined in table 4. The results show that there is a high risk of mortality for recently widowed husbands and wives. Furthermore, the hazard is higher (not significant) in wives versus husbands during the first 12 months following bereavement.

Figure 4.

HRs of widowed husbands and wives versus their married counterparts according to time since bereavement (months; design provided in table 4); * and ** on the top of the blocks represent the significance of HRs with p<0.05 and p<0.001, respectively.

The range of p values provided in figures 2–4 indicates the significance of each of the HRs. For example, in figure 4, the p value=0.0001 associated with the HR=1.39 (men; TSB range <6 months) strongly indicates that the HR is significantly >1. Similarly, the p value=0.039 associated with the HR=1.15 (men; TSB 37–48 months) weakly indicates the significance of the HR >1.

Graphical checks of the overall adequacy of the CPH models were performed.18 19 Based on the Cox-Snell residuals plot, the final model gave a reasonable fit to the data (data not shown). The deviance residual plots revealed no obvious outliers in the data (data not shown). Furthermore, the Wald test statistic was used to test the fit of the final model,18 and according to this test statistic, the final model fits the data reasonably well (see online supplementary tables S1–S3).

Discussion

This is the first comprehensive study to evaluate the relationship between bereavement and social support in the Amish population. This study provides evidence that Amish widows and widowers have an increased mortality risk compared with married cohort members. Although it is difficult to determine whether this effect is of equivalent magnitude as that observed in studies of other populations, the most recent studies of the bereavement effect using the CPH suggest that our findings are generally consistent with data from other populations.4

Several previous studies on American, European and Middle Eastern populations have found that mortality is magnified in individuals widowed at a younger age and that widowers have a higher mortality risk than widows.3 5 8 16 20 22 The LDS study is closest to our study because of the large family sizes and the population selected as a religious isolate.8 The effects of bereavement on mortality with respect to gender and the age at widowhood ranges observed in the Amish are also largely consistent with those observed in the LDS population,8 and other populations such as Finland and Israel (figure 3).6 22 As expected, widowers showed higher HRs than widows, except for the 1850–1875 cohort (figure 2).

In the present study, the association between bereavement and mortality is greater in the first 6 months for men and women (figure 4), consistent with previous findings.2 3 5 20 21 23 The mortality risks in the first 6 months are lower in the Amish (figure 4) compared with some,2 5 20 21 but not all, studies.3 23 One common pattern observed in this and other studies is that the bereavement effect is higher in the first 6 months and later life.3 23 We did a regression analysis for trend in the data of figure 4 and there is no significant declining trend after the first 6 months. We speculate that the higher mortality during the first 6 months might reflect acute effects related to the loss of a spouse, while the higher mortality in later life might reflect decreased survival from ageing-related diseases that is unmasked in the absence of spousal support.

One strength of our study is that we could evaluate the effect of remarriage because there were a substantial number of widowed individuals who did and did not get remarried (table 1). Shor et al4 noted the difficulty in studying the effect of remarriage in populations where all individuals are deceased because “In previous decades, widowed men almost always remarried”. As suggested by previous studies,8 9 remarriage after the death of a spouse significantly influences the bereavement effect because it is associated with an increased survival of men and women across all cohorts. This association is likely influenced by the fact that men or women who get remarried are in sufficiently good physical and mental health to do so. Furthermore, the survival rate is higher for men compared with women, possibly reflecting support in the Amish society for men getting remarried.

Interestingly, more children at the time of the death of the first spouse was associated with an increased risk of death, though the HR for having >6 surviving children compared with ≤2 was not significantly greater than 1.0. This result does not support the hypothesis that more surviving children confer a survival advantage to parental longevity, as perhaps by providing social support for their parents. Spouses in the Amish society may also provide a unique emotional, psychological and social support to each other which cannot be provided by their surviving children. The lack of protective association was similarly observed when the number of surviving children was considered as a linear or as a categorical variable (data not shown). This contrasts with the data from the Utah Population Database, in which increasing numbers of children were associated with a decreased HR.8 We considered the number of surviving children as a separate term (table 2), but did not evaluate the interaction of the number of surviving children with widowhood.

The implication of these findings is that differential familial support following bereavement does not appear to be the key factor affecting mortality increases in widowed Amish populations. One potential explanation is that spouses, as ‘attachment figures,’ provide a unique, irreplaceable social support which must be considered independently from other ancillary support providers, such as children.24 Data suggesting that relative mortality risk is also elevated in divorced and never-married populations may support this hypothesis.3 In addition, quality of social support has significantly greater effects on well-being than quantity of support in elderly populations of both sexes.25

In adults aged 65 and older, lower reported social support has been associated with decreased life satisfaction and increased depressive symptoms.26 Family members and close friends should be especially vigilant during the sensitive acute period following the loss of a spouse, when relative mortality risk is the highest.

There are two limitations of our data. First, the number of surviving children covariate was simplified because it was treated as a time-independent covariate, although some children die before their parents, so it could be considered as time-dependent instead. Second, the causes of death were unavailable. Future research is needed to study the effect of the loss of a child on the mortality of husbands and wives by considering the number of surviving children as a time-dependent covariate. Also, research is needed to determine whether differential measures of social support may be associated with certain causes of death in widowed populations. Divorce in the Amish population is sufficiently rare that this was not a major potential source of error.

Our study results indicate that remarriage plays an important role in improving the survival rate of men and women in the Amish population. Contrary to the results from previous studies, an increase in the number of surviving children was associated with a decreased survival rate of Amish individuals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank two reviewers for excellent suggestions that led us to improve the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: BDM conceived the study. AS and SS did the research and data analysis, with substantial guidance from PFM, BDM and AAS. AS and SS wrote the manuscript, with substantial editing by PFM, BDM and AAS. AAS managed the project with assistance from BDM. AAS manages the Anabaptist Genealogy Database (AGDB) project at the National Institutes of Health and KAR managed the AGDB data at the University of Maryland Medical School during the period of this project. ARS provided resources and advice. All authors proofread and approved the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by research grants R01 HL69313, R01 DK54261, R01 AG1872801, R01 HL088119, R01 AR046838 and U01 HL72515 from the National Institutes of Health. This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Programme of the National Institutes of Health, NLM and the Geriatric Research and Education Center, Baltimore Veterans Administration Medical Center.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The construction and maintenance of Anabaptist Genealogy Database (AGDB) are covered under an IRB-approved human subjects protocol at the National Institute of Health (NIH), Leslie Biesecker, Principal Investigator. National Human Genome Research Institute Institutional Review Board at the National Institutes of Health.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data from the Anabaptist Genealogy Database (AGDB) are available to investigators (including ARS and various others not participating in this study) who have an IRB-approved protocol to study the Amish or other Anabaptist groups. Investigators can request access to AGDB by writing to AAS and to Dr Biesecker.

References

- 1.Jagger C, Sutton CJ. Death after marital bereavement—is the risk increased. Stat Med 1991;10:395–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schaefer C, Quesenberry C, Wi S. Mortality following conjugal bereavement and the effects of a shared environment. Am J Epidemiol 1995;141:1142–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson NJ, Backlund E, Sorlie PD, et al. Marital status and mortality: the national longitudinal mortality study. Ann Epidemiol 2000;10:224–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shor E, Roelfs DJ, Curreli M, et al. Widowhood and mortality: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. Demography 2012;49:575–606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manor O, Eisenbach Z. Mortality after spousal loss: are there socio-demographic differences? Soc Sci Med 2003;56:405–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martikainen P, Valkonen T. Mortality after the death of a spouse: rates and causes of death in a large Finnish cohort . Am J Public Health 1996;86:1087–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Espinosa J, Evans WN. Heightened mortality after the death of a spouse: marriage protection or marriage selection? J Health Econ 2008;27:1326–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mineau G, Smith K, Bean L. Historical trends of survival among widows and widowers. Soc Sci Med 2002;54:245–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Helsing KJ, Szklo M, Comstock GW. Factors associated with mortality after widowhood. Am J Public Health 1981a;71:802–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stroebe W, Stroebe MS, Abakoumkin G. Does differential social support cause sex differences in bereavement outcome? J Community Appl Soc Psychol 1999;9:1–12 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stroebe MS, Stroebe W, Schut H. Gender differences in adjustment to bereavement: an empirical and theoretical review. Rev Gen Psychol 2001;5:62–83 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hostetler JA. Amish society. 4th edn MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwasaki M, Otani T, Sunaga R, et al. Social networks and mortality based on the Komo-Ise Cohort Study in Japan. Int J Epidemiol 2002;31:1208–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agarwala R, Biesecker LG, Hopkins KA, et al. Software for constructing and verifying pedigrees within large genealogies and an application to the old order Amish of Lancaster County. Genome Res 1998;8:211–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitchell BD, Lee W-J, Tolea M, et al. Living the good life? Mortality and hospital utilization patterns in the Lancaster County Amish. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e51560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith KR, Zick CD. Risk of mortality following widowhood: age and sex differences by mode of death. Soc Biol 1996;43:59–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.R Development Core Team R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2011. http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 18.Therneau TM, Grambsch PT. Modeling survival data: extending the Cox model statistics for biology and health. New York, NY: Springer, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tableman M, Kim JS. Survival analysis using S: analysis of time-to-event data. 1st edn. New York, NY: Texts in Statistical Science, Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lichtenstein P, Gatz M, Berg S. A twin study of mortality after spousal bereavement. Psychol Med 1998;28:635–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mendes De Leon CF, Kasl SV, Jacobs S. Widowhood and mortality risk in a community sample of the elderly: a prospective study. J Clin Epidemiol 1993;46:519–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peritz E, Bialik O, Groen JJ. Mortality by marital status in the Jewish population of Israel. J Chronic Dis 1967;20:823–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hart CL, Hole DJ, Lawlor DA, et al. Effect of conjugal bereavement on mortality of the bereaved spouse in participants of the Renfrew/Paisley Study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2007;61:455–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diamond LM. Contributions of psychophysiology to research on adult attachment: review and recommendations. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 2001;5:276–95 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Antonucci TC, Akiyama H. An examination of sex differences in social support among older men and women. Sex Roles 1987;17:737–49 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newsom JT, Schulz R. Social support as a mediator in the relation between functional status and quality of life in older adults. Psychol Aging 1996;11:34–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.