Abstract

Objective

Lean interventions aim to improve quality of healthcare by reducing waste and facilitate flow in work processes. There is conflicting evidence on the outcomes of lean thinking, with quantitative and qualitative studies often contradicting each other. We suggest that reviewing the literature within the approach of a new contextual framework can deepen our understanding of lean as a quality-improvement method. This article theorises the concept of context by establishing a two-dimensional conceptual framework acknowledging lean as complex social interventions, deployed in different organisational dimensions and domains. The specific aim of the study was to identify factors facilitating intended outcomes from lean interventions, and to understand when and how different facilitators contribute.

Design

A two-dimensional conceptual framework was developed by combining Shortell's Dimensions of capability with Walshes’ Domains of an intervention. We then conducted a systematic review of lean review articles concerning hospitals, published in the period 2000–2012. The identified lean facilitators were categorised according to the intervention domains and dimensions of capability provided by the framework.

Results

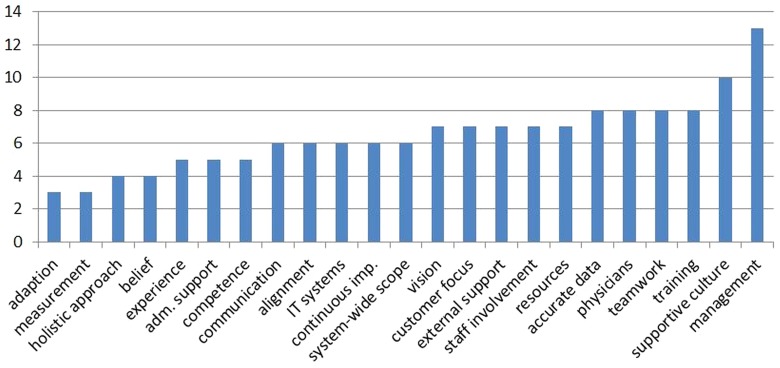

We provide a framework emphasising context by relating facilitators to domains and dimensions of capability. 23 factors enabling a successful lean intervention in hospitals were identified in the systematic review, where management and a supportive culture, training, accurate data, physicians and team involvement were most frequent.

Conclusions

In the absence of evidence, the two-dimensional framework, incorporating the context, may prove useful for future research on variation in outcomes from lean interventions. Findings from the review suggest that characteristics and local application of lean, in addition to strategic and cultural capability, should be given further attention in healthcare quality improvement.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This review of reviews sums up the major findings regarding facilitators for lean interventions in healthcare in the latest decade.

The immaturity of the research field makes it hard to find substantial evidence for effective lean interventions in healthcare.

The fact that lean is a social, complex and context-dependent intervention calls for a shift from cause–effect to conditional attributions in research.

Introduction

Lean thinking has been introduced in healthcare during the latest decades as a quality-improvement method.1 Lean can be challenging to adopt in a medical environment, where professionals require evidence before taking action.2–4 Researchers remark a profound gap and tension between the medical approach and lean thinking.5 6 The call for scientific proof for lean as an efficient and effective quality-improvement method is strong.7 The lack of evidence may lead to resistance and hinder speed-up and spread of quality initiatives in healthcare.1 8–10

Lean interventions aim to improve quality by reducing waste and facilitate flow in care processes.11 Lean techniques include value stream mapping of start-to-end processes, identification and elimination of activities that do not add value and streamlining of value-adding activities.12 A focus on measurements and continuous improvement is expected to promote implementation and sustainability.

In a recent review, Mazzocato et al13 concluded that lean has been applied successfully in healthcare institutions worldwide. However, most studies have a narrow technical application with a limited organisational reach. Many are single case studies, some quite anecdotal, while others are biased or characterised by a weak study design. Some reviews suggest that inappropriate analyses, a lack of alternative hypotheses and other methodological limitations undermine the validity.2 5 14 This makes it difficult to rule out confounding explanatory factors, to measure the outcomes and generalise the results from lean interventions.6

Advocates for experimental designs question results from qualitative studies, and argues that randomised controlled trials are necessary to isolate effects.15 16 Many studies using an experimental design did not find any significant effect of lean and other quality-improvement interventions.1 2 6 9 10 17 Experimental methods are not very helpful in understanding interventions’ effectiveness because they rule out context, content and application variables.9 We cannot be sure that the specific intervention—and not other factors—produced the observed change.2 10

The key problem is the adaption of study designs that do not allow drawing solid conclusions, particularly as they fail to take into account contingency factors that are needed to translate the findings from one setting to another. Is there a cure for this lack of evidence? On a paramount level, one must ask whether the absence of evidence justifies inaction.18 The quality chasm between the healthcare we have and the healthcare we should have is well documented.1 19 20 In other words, the call for action is still there, and, these obstacles to quality improvement must be crossed.

Lean as social, complex and context-dependent interventions

Shortell et al21 emphasised the need to link evidence-based medicine and what they refer to as evidence-based management, arguing that medicine must take into account the complex organisational and social context in which care is delivered. Such integration of the intervention and its context seldom happens in quality-improvement research.22

Lean interventions operate differently from the clinical interventions affecting biological systems, in which a linear cause–effect relationship controlling the influence of context is assumed. A context is simply defined as all surrounding factors that are not part of the intervention itself.8 23 However, the boundaries between the intervention and its surroundings may be relatively arbitrary, as lean interventions are social, complex and inherently context-dependent.24 25 Lean interventions consist of multiple, reciprocally interacting elements. They evolve over time in response to continuous feedback as situation-dependent cumulative processes, and are therefore intrinsically unstable and difficult to standardise. Lean and other quality-improvement methods are often adjusted, mixed, implemented and used simultaneously.5 10 26 27 This fact challenges the strict distinction between lean and other quality-improvement methods. Finally, lean interventions are open systems that feed back on themselves, so that with learning, they may change the conditions that made them work in the first place.

There is a growing literature on lean facilitators. According to Grimshaw et al,28 systematic reviews provide the best evidence on the effectiveness of quality improvement. We observe a growing consensus that characteristics such as management, resources and culture matter, but the current knowledge base lacks specification on when and how the different facilitators work. This vagueness partly rests on insufficient methodological attention to the context in which lean interventions work. To understand and assess variation in lean intervention success, there is a need for a conceptual framework defining facilitators for change at the stages and levels where they are activated. These facilitators, also named enablers, determinants for effectiveness and so on, may be defined as contingency factors which help the progress of lean interventions,8 22 29 and shift the focus from cause–effect to conditional attributions.

The University Hospital of North Norway underwent a complex merger and restructuring process between 2007 and 2010.30 An enterprise-wide lean programme for improvement was launched. The programme aimed to accomplish quality improvement in parallel with the organisational change to counteract the transitional setbacks in quality that large-scale change may entail.31 A research programme was established to evaluate the effects. The proposed framework represents a theoretical tool to understand more of how and when lean interventions work at the hospital. Our approach incorporates the complex social and organisational context in which the interventions are applied and the different stages of adoption. We suggest that the emerging knowledge could guide decision-makers considering lean interventions, assessing the organisations’ readiness for change.22 32 The specific aim of the study was to identify contingency factors influencing intended outcomes of lean interventions, and to understand when and in which dimension different factors contribute.

Methods

A systematic narrative review33 of reviews of quality improvement in hospitals was conducted. One reviewer performed the systematic review, supervised by the two coauthors. Any confusion was resolved by discussion involving all three authors. The initial inclusion criteria were English language articles published in a peer-reviewed journal in the period 2000–2012. The search words included hospital, healthcare, quality improvement, lean thinking, lean management and review/evaluation. By searching PubMed, Web of Science, EMBASE, Cochrane and Scopus, 251 articles were identified. A snowball approach was used to search for supplementary articles, adding 13 articles. Fifteen duplicate articles were removed. The titles and abstracts of these 249 articles were screened according to the Prisma guidelines for reporting reviews and meta-analysis (see online supplementary material).34 One hundred and ninety-six original articles were excluded. Exclusion criteria included the absence of a hospital or organisational focus, single-unit case studies and hybrid quality-improvement approaches. As a result, 53 articles were assessed for eligibility. After a full-text review, another 35 articles were excluded by the criteria that neither large-scale quality improvement, success criteria nor lean thinking were issued. Articles that mainly represented practical guidelines were also excluded. The final review included 18 articles.10 13 17 22 23 26 27 31 35–44

Data analysis

The 18 articles were systematised according to the number of studies included in each review. Eight articles reviewed a number of definite cases, varying from 4 to 90 (median 33). The remaining articles were expert evaluations, narrative or unsystematic reviews, all covering lean interventions in hospitals. Half of the articles review only lean interventions, while the others include lean and corresponding methods such as Productive ward and process-oriented redesign. Lean was extracted and treated separately as far as possible, though confined by the observed mix, similarity and simultaneous use of different quality-improvement methods in hospitals.5 22 26 27 The methods used in the original studies were qualitative, quantitative or a mixed-method approach. Most studies were based on cases originated in the USA, Australia and Great Britain.

The next step was to search for facilitators, defined as contingency factors predicted to promote quality improvement, as opposed to barriers that hinder improvement.37 The decision to concentrate on facilitators and not on barriers to lean improvement was based on the fact that the research literature at this field chiefly pays attention to facilitators and not to barriers.5 8 10 13 17 22 23 38 In most cases, the facilitators were quite easy to identify in the texts despite different annotations used, including enablers, conditions, factors and key facilitators, critical elements, determinants of effectiveness, and contextual characteristics. Using the method of feature maps, which enable localisation of similarities and differences among studies,33 the articles were systematically analysed and recorded in a standardised format, according to the facilitators. The procedure was conducted by creating a worksheet categorising every article according to the author, year of publishing, type of review, other quality-improvement methods comprised (in addition to lean), research method, labelling of facilitators and facilitating factors. The complete worksheet is attached as an online supplementary material.

All the identified facilitators were assigned to larger categories. This classification was carried out to develop a more specific and practically focused state of knowledge concerning facilitators for lean thinking, as the need for an overview necessitated reducing the information to manageable amounts. All the identified facilitators concerning management and leadership were placed in the category management, covering subjects such as management support, commitment and ownership. Cultural issues were all categorised as supportive culture, including views, norms, beliefs and behaviours supporting the principles and practice of quality improvement. All facilitators concerning local translation were put in the category adaption, as all facilitators dealing with prior involvement in quality-improvement work were grouped under the heading experience, and so on. After examining all the 149 facilitators, grouping them with similar ones, we ended up with a list comprising 23 facilitators. The different facets of these facilitators are all listed in box 1. Finally, the frequency of each of the facilitators in the 18 reviews was accounted for.

Box 1. Facilitators for change: description.

Adaption: Local translation of the lean intervention

Measurement: Audits local performance metrics on regular basis as evidence

Holistic approach: Lean as an entire value system, embracing every day improvement

Belief: In staff and patient, benefits encourage willingness and motivation

Experience: Prior quality improvement using a successful, mature method

Administrative support: Practical facilitation by a project management

Competence: In tools, assumptions and methods assure capability

Communication: With and between patients and staff, including feedback to both

Alignment: Consistency to strategic objectives and priorities of strategic importance

IT-systems: Adequate IT support and infrastructure established

Continuous improvement: A long-term plan, securing endured and sustained attention

System-wide scope: Multifaceted interventions across silos and functional divides

Vision: Targets of urgency and direction, but realistic, simple and practical solutions

Customer focus: Includes patient and workforce value creation and improvements

External support: Expert change agents, networks and sponsorship trigger change

Staff involvement: Commitment, engagement and empowerment by staff participation

Resources: Available, sufficient and accessible capacities

Accurate data: Robust and timely, evidence-based data as a impetus to change

Physicians: Clinical leadership and champions’ engagement, support and collaboration

Teamwork: Multiskilled and disciplinary team collaboration including decision-making

Training: Accessible, substantial, practical and relevant training for immediate use

Supportive culture: Views, norms and beliefs that support quality improvement

Management: Leadership support, ownership and commitment

A theoretical and methodological framework

Lean interventions consist of several different phases, from planning and preparation to implementation and sustainability, involving different organisational capabilities. The facilitators for improvement were analysed and reorganised in a table combining Shortell's dimensions of capability2 45 and Walshe's domains of an intervention.9 Shortell categorised improvement factors according to cultural, technical, strategic and structural dimensions of an intervention. The cultural dimension refers to the underlying beliefs, values, norms and behaviours of the organisation. The technical dimension covers training and information system issues, while the strategic dimension emphasises the conditions that offer the greatest opportunities to change. This dimension touch on the degree of integration of quality improvement in the hospital's strategic plans, and to which extent improvement efforts are devoted to processes central to strategic priorities. The structural dimension relates to mechanisms that facilitate learning and disseminate best practices throughout the organisation. The four dimensions are multiplicative, inter-related and equally necessary for lasting quality improvement according to Shortell. Varying lean success can be understood as a result of the interplay of dynamic processes related to the four dimensions.45

Walshe's differentiated domains in quality interventions are labelled as context, content, application and outcomes. The context involves the situation, setting or organisation in which the intervention is deployed. Context may vary widely, within and between hospitals. The content describes the nature or characteristics of the intervention itself. The content of lean may be standardised and repeatable or modified and easy to redesign. The application covers the process through which the intervention is delivered. This process may be protocol-driven or widely varying depending on local actors. Outcomes are the results of the intervention, including the maintenance phase after implementation. All of these domains may be characterised by low or high variance. High levels of variance in the settings, content and application may explain interventions of varying success. Variances also reduce the ability to generalise empirically, and to draw conclusions about effects from one specific context to another. The complex relationship between context, content, application and outcomes must be unpicked to develop a situational understanding of effectiveness.9

By combining Shortell's dimensions and Walshe's domains, this two-dimensional framework made it possible to classify identified facilitators for quality improvement, as emerging in different domains in a multistage process and by different organisational dimensions. The framework was used to describe and understand the contextual factors encountered in an organisational-wide quality-improvement effort.

Results

Among the 18 reviewed articles, 149 facilitators for lean interventions were found. The reviews identified 3–16 (median 7) facilitators for improvement. All were identified in several reviews, varying from 3 to 14 (median 7) times. The facilitators were categorised into 23 extensive classes, covering the range of all the identified facilitators.

Figure 1 shows how frequent the different facilitators were identified in the 18 reviews.

Figure 1.

Frequency of different facilitators identified in 18 reviewed articles.

Discussion

Table 1 shows how the different facilitators were found relevant in different intervention domains and affected organisational dimensions.

Table 1.

Facilitators for change, literature reviews 2000–2012

| Dimensions of capability | Domain of the intervention |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Context | Content | Application | Outcomes | |

| Situation and organisation | Characteristics of the intervention | Local delivery process | Results and maintenance | |

|

Cultural Underlying beliefs, values, norms and behaviour |

Experience Belief |

Adaption Customer focus |

Teamwork | Supportive culture |

|

Technical Training and info support systems |

IT systems Competence |

Training | Administrative support | Communication |

|

Strategic Strategic importance and opportunity to change |

Alignment Vision |

Resources | Physicians Management |

Holistic approach Continuous improvement |

|

Structural Mechanisms to facilitate learning and disseminate best practices |

External support | Accurate data | Staff involvement | Measurement System-wide scope |

Context: situation and organisation

Prior experience, accompanied by success stories demonstrating the benefits for patients and staff, enables improvement.23 31 37 This relates to the organisation's cultural capability and the influence of the underlying beliefs, values, norms and behaviours. Motivation influences the willingness to participate.13 17 37 38 40 41 44 IT systems’ infrastructure and competence,17 23 31 36–38 as well as external experts sponsoring, strengthen the technical and structural capability. Sponsorship triggers learning and contribute to dissemination of best practices throughout the organisation.17 31 35 38–40 44 Competence in tools and methods supports the assumptions of lean, and increases the potential for change.26 27 36 38 Ambitious targets aligned with the hospital's overall goals and strategies strengthen the strategic capability.17 31 36 38 41 44 The goals have to be of strategic importance, but at the same time realistic, based on simple and practical solutions.17 22 31 36 40 44

Content: characteristics of the intervention

Adaption and translation to local conditions are a precondition for success.26 35 37 A methodology communicating a clear patient and workforce focus supports the cultural dimension. Emphasis on patient processes, value creation and patient's needs facilitates quality improvement in healthcare.10 13 23 35 37 42 44 Access to and accomplished substantial training in methods and tools strengthen the organisations’ technical capability,10 17 22 26 31 35 36 38 44 as sufficient and available resources, financial as well as staff time, affect the strategic dimension.10 17 22 23 31 35 36 38 44 On the structural dimension, accurate and robust data represent an impetus to learning and spread of best practices. Timely data contribute to an evidence-based quality-improvement initiative.13 17 36 37 39 40 44 Availability and sufficiency of training, data and other resources are among the most frequent facilitators in the reviewed articles, and thereby probably among the most important drivers for change.

Application: local delivery process

Collaborating multidisciplinary and multiskilled teams facilitates local application of lean.23 31 35–38 42 43 Strengthening the improvement culture presupposes workforce stability, team leadership and decentralised decision-making. Administrative project management and practical support secures backing, and contributes to the technical capability.22 31 36 44 Strategically, involvement of physicians and management encourage change. Management engagement includes frontline and senior managers, maintaining urgency, setting direction, reinforcing expectations and providing resources.10 13 17 22 23 31 35 36 38–42 44 Physicians represent champions and clinical leadership, and their involvement, engagement and collaboration are important at the strategic level as role models and peers for others.10 17 23 31 36 38 40 43 The management and physicians’ involvement are among the most frequently identified enablers jointly with teamwork. Key factors to disseminate best practices are staff participation, engagement and empowerment. Staff commitment, responsibility and ownership are required for achieving longstanding outcomes.26 35 38–42 44

Outcomes: results and maintenance

To secure maintenance, a hospital depends first and foremost on a supportive culture characterised by norms, beliefs and behaviours supporting the principles and practice of quality improvement.10 22 23 35–38 In a supportive culture, employees feel that they can make use of their skills and creativity, take initiative and cause things to happen.35 At the technical dimension, communication and feedback between patients and staff are enablers.31 35 38 43 44 Strategically, a holistic approach based on continuous improvement and sustained attention affects the ability to accomplish change. A holistic approach emphasises that lean is not only a strategy to promote everyday improvement but also a philosophy of ongoing quality improvement within the hospital's value system.13 17 27 35 41 A long-term plan should be established to secure continuous improvement.10 13 17 26 27 37 Local audits and measurements conducted on a regular basis relate to the organisation's structural capability, which strengthens the evidence for lean interventions.36 37 39 40 A system-wide multifaceted approach, across functional divides, allows best practices to be learned and disseminated.

Analysis based on the conceptual framework suggest that understanding which facilitators influence the intervention at different domains and dimensions of capability is probably more important than a quantitative approach.8 17 This represents a shift from cause–effect to conditional attributions.45 Each domain and dimension is influenced by the status of other ones. Our results summarised in table 1 indicate that a number of facilitators may interact within and between the domains and dimensions. The four dimensions, domains and the associated facilitators are inter-related and probably all necessary to achieve longstanding results.2 Finally, we elaborate our interpretation of these findings.

Our analyses of data from previous review articles within this new framework show that successful lean interventions share some common features. We identified 23 facilitators associated with successful interventions. Unfortunately, little is known about which facilitators are most important.8 22 Management and leadership engagement were identified as important by 13 of the 18 reviewed reviews. The other facilitators most frequently identified were a supportive culture, accurate data and training, along with physician and team involvement. This is in accordance with the conclusions from relevant research, and may indicate that these facilitators are vital to accomplish quality improvement.13 23 31 35 Two recent reviews conclude that leadership, culture, maturity and data infrastructure have a stronger evidence base than other factors.23 38 Our results, nevertheless, suggest that successful interventions must utilise multiple facilitators from the four dimensions of capability, interplaying as the change processes that touch on different domains. The observation the facilitators identified in this study were in accordance with those promoted in other broader theories of implementation concerning uptake of evidence and innovations in healthcare4 23 46 strengthens the findings.

The most frequent facilitators belong to the content or application part of the intervention. This may indicate that policymakers should pay special attention to the content of lean and the local delivery process. Sufficient resources, accurate data and training are crucial for lean interventions to succeed. Lean interventions are not a recipe that can be implemented locally if the training or available resources are inadequate. The need for local resource allocation should not be underestimated. This is in accordance with Radnor et al,27 who advocated that lean interventions must be contextualised, rather than transplanted like a recipe.

This assertion is supported by the frequently identified facilitators labelled physicians and management. Leadership and clinical leadership are keys to understand why, or why not, lean interventions make contributions to healthcare.47 Finally, the local application of lean in hospitals depends heavily on teamwork by multiskilled and multidisciplinary teams. Work-floor staff must be engaged and empowered. Womack and Jones,12 who initially advocated lean thinking in healthcare, emphasised the multiskilled teams as a main advantage for hospitals, making lean interventions suitable for healthcare.

The cultural and strategic dimensions of capability embrace most of the frequent facilitators. A supportive culture is fundamental to achieve quality improvements.38 The organisational culture and the strategic importance of the patient path exposed to the improvement initiative are essential to understand variation in outcomes of lean interventions. Available resources, physicians’ and managements’ involvement indicate and affect the strategic importance, and thereby the opportunity to change. These findings are supported by other recent hospital-based studies, like Rozenblum et al.47

Limitations

Making these interpretations from a systematic review of reviews must take the methods’ limitations into consideration. The facilitators were grouped with similar ones, and sometimes renamed, risking that the original meaning could be misread and mistranslated by our interpretation. Transparency is promoted by conducting feature maps and presenting all the identified facilitators in appendices.

It could be argued that facilitators identified in large reviews should be given more weight than those identified in smaller ones. However, our analysis identified the same facilitators across small and large reviews. Therefore, weighting was not conducted, even though we suggest that facilitators identified in many studies are significant.

Including qualitative and quantitative studies eliminates the possibility of quantifying the findings and predicting the effects of the various facilitators by meta-analysis. The inclusion of both types of studies broadens the scope, increase the ability to identify an ampler spectre of facilitators and contribute to understanding the role of context in lean interventions.

Directions for future research

A critical review concluded that most of the research on hospital quality is dominated by questions of what and does not go further to investigate the how, when and why.48 They called for approaches that incorporate structure, process and outcomes. The fact that we know so little about the relationship between these makes it difficult to recommend ways of organising that could improve patient care.49

The facilitators identified and the two-dimensional framework proposed in the present work incorporate structure and process. Still, the facilitators are characterised by vagueness, as broad and comprehensive determinants, that needs further specification and practical content to guide future effective quality improvements to healthcare organisations.8 22 38 50 In addition to contextual preconditions, success are dependent on how an organisation utilises, combines and sequences organisational resources and routines.32 A logical next step will be to measure and analyse outcomes in the context of this framework, with the identified facilitators as explanatory variables. Possible measures of outcomes could be related to the healthcare providers’ performance (adherence to recommended practice), patient's outcome (as quality of life or mortality), surrogate outcomes (as re-admission) and organisational outcomes (such as resource use or sustainability).36 At the University Hospital of North Norway, more than 5 years of lean experience and more than 20 implemented lean interventions leave us with a sufficient amount of empirically based cases to assess due to varying success.

Conclusion

The findings contribute to reduce the gap between theory and practice, by a shift in focus from cause-effect to conditional attributes or characteristics of an effective organisation-wide quality intervention. The review of reviews identified 23 inter-related facilitators for lean in hospitals, where management engagement, cultural support, accurate data and training, along with teamwork, physician and staff involvement were most frequent. The findings suggest that characteristics of lean and the local application should be given attention, in addition to the organisations’ cultural and strategic capability.

The main contribution of this review is a two-dimensional framework for identification and analysis of facilitators for lean interventions in healthcare. This framework incorporates the complex social and organisational context in which lean interventions are applied. These findings coincide with recent research calling for more attention to the influence of organisational context when trying to understand variance in interventions in healthcare.23 We suggest that it will prove useful in future research aiming for a better understanding of how the likelihood to accomplish success in lean interventions can be increased.14 The framework will also be used in future research locally at the hospital, as a practical tool to assess variation in adoption of lean.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank David Greenfield (PhD) and John Øvretveit (PhD) for their assistance in clarifying concepts in the discussion. They would also like to thank James Morrison for his language assistance.

Footnotes

Contributors: HA contributed to the conception and design, the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data, as well as drafting and revising the article. TI and KAR made a substantial contribution to the design and interpretation of the data, as well as to drafting and critical revising of the article. All the authors have provided final approval of the submitted manuscript.

Funding: The PhD study is founded by the regional health trust of North Norway, Helse Nord RHF.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data worksheet is available as a supplementary file. The dataset will be made available by the corresponding author on request.

References

- 1.Joosten T, Bongers I, Janssen R. Application of lean thinking to health care: issues and observations. Int J Qual Health Care 2009;21:341–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shortell SM. Assessing the implementation and impact of clinical quality improvement efforts: abstract, executive summary and final report. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shojania KG, Grimshaw JM. Evidence-based quality improvement: the state of the science. Health Aff 2005;24:138–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rycroft-Malone J, Kitson A, Harvey G, et al. Ingredients for change: revisiting a conceptual framework. Qual Saf Health Care 2002;11:174–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Young T, McClean SI. A critical look at lean thinking in healthcare. Qual Saf Health Care 2008;17:382–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alexander JA, Hearld LR. What can we learn from quality improvement research? A critical review of research methods. Med Care Res Rev 2009;66:235–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Souza LB. Trends and approaches in lean healthcare. Leadersh Health Ser 2009;22:121–39 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Øvretveit J. Understanding the conditions for improvement: research to discover which context influences affect improvement success. BMJ Qual Saf 2011;20(Suppl 1):i18–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walshe K. Understanding what works—and why—in quality improvement: the need for theory-driven evaluation. Int J Qual Health Care 2007;19:57–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Øvretveit J, Gustafson D. Evaluation of quality improvement programmes. Qual Saf Health Care 2002;11:270–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liker JK, Kaisha TJKK. The Toyota way: 14 management principles from the world's greatest manufacturer, McGraw-Hill, New York, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Womack JP, Jones DT. Lean thinking: banish waste and create wealth in your corporation, revised and updated, Free Press, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mazzocato P, Savage C, Brommels M, et al. Lean thinking in healthcare: a realist review of the literature. Qual Saf Health Care 2010;19:376–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kontos PC, Poland BD. Mapping new theoretical and methodological terrain for knowledge translation: contributions from critical realism and the arts. Implement Sci 2009;4:1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008;337:a1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perneger T. Ten reasons to conduct a randomized study in quality improvement. Int J Qual Health Care 2006;18:395–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Powell A, Rushmer R, Davies H. A systematic narrative review of quality improvement models in health care. Social Dimensions of Health Institute at The Universities of Dundee and St Andrews, 2008

- 18.Altman DG, Bland JM. Statistics notes: absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. BMJ 1995;311:485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corrigan JM. Crossing the quality chasm, Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kohn LT, Corrigan J, Donaldson MS. To err is human: building a safer health system, Joseph Henry Press, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shortell SM, Rundall TG, Hsu J. Improving patient care by linking evidence-based medicine and evidence-based management. JAMA 2007;298:673–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walshe K, Freeman T. Effectiveness of quality improvement: learning from evaluations. Qual Saf Health Care 2002;11:85–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaplan HC, Brady PW, Dritz MC, et al. The influence of context on quality improvement success in health care: a systematic review of the literature. Milbank Q 2010;88:500–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davidoff F. Systems of service: reflections on the moral foundations of improvement. BMJ Qual Saf 2011;20(Suppl 1):i5–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G, et al. Realist review—a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. J Health Ser Res Policy 2005;10:21–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walshe K. Pseudoinnovation: the development and spread of healthcare quality improvement methodologies. Int J Qual Health Care 2009;21:153–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Radnor ZJ, Holweg M, Waring J. Lean in healthcare: the unfilled promise? Soc Sci Med 2012;74:364–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grimshaw J, McAuley L, Bero L, et al. Systematic reviews of the effectiveness of quality improvement strategies and programmes. Qual Saf Health Care 2003;12:298–303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shortell SM, Bennett CL, Byck GR. Assessing the impact of continuous quality improvement on clinical practice: what it will take to accelerate progress. Milbank Q 2001;76:593–624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ingebrigtsen T, Lind M, Krogh T, et al. Merging of three hospitals into one university hospital. Tidsskr Nor Lægeforen 2012; 132:813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vos L, Chalmers SE, Dückers MLA, et al. Towards an organisation-wide process-oriented organisation of care: a literature review. Implement Sci 2011;6:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weiner BJ. A theory of organizational readiness for change. Implement Sci 2009;4:67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hart C. Doing a literature review. London: Sage Publications, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Poksinska B. The current state of lean implementation in health care: literature review. Qual Manag Healthcare 2010;19:319–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brennan S, McKenzie JE, Whitty P, et al. Continuous quality improvement: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes (Protocol). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009;4:CD003319. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003319.pub2 [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Souza LB, Pidd M. Exploring the barriers to lean health care implementation. Public Money Manag 2011;31:59–66 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaplan HC, Provost LP, Froehle CM, et al. The Model for Understanding Success in Quality (MUSIQ): building a theory of context in healthcare quality improvement. BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21:13–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim CS, Spahliner DA, Billi JE. Creating value in health care: the case for lean thinking. JCOM 2009;16:557–62 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim CS, Spahlinger DA, Kin JM, et al. Implementation of lean thinking: one health system's journey. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2009;35:406–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lukas CVD, Holmes SK, Cohen AB, et al. Transformational change in health care systems: an organizational model. Health Care Manag Rev 2007;32:309–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kollberg B, Dahlgaard JJ, Brehmer PO. Measuring lean initiatives in health care services: issues and findings. Int J Productivity Perform Manag 2007;56:7–24 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Winch S, Henderson AJ. Making cars and making health care: a critical review. Med J Aust 2009;191:415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morrow E, Robert G, Maben J, et al. Emerald article: implementing large-scale quality improvement: lessons þÿfromTheProductiveWard: ReleasingTimetoCare! Qual Assur 2012;25:237–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O'Brien JL, Shortell SM, Hughes EFX, et al. An integrative model for organization-wide quality improvement: lessons from the field. Qual Manag Healthcare 1995;3:19–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, et al. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q 2004;82:581–629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rozenblum R, Lisby M, Hockey PM, et al. The patient satisfaction chasm: the gap between hospital management and frontline clinicians. BMJ Qual Saf 2013;22:242–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hearld LR, Alexander JA, Fraser I, et al. Review: how do hospital organizational structure and processes affect quality of care? A critical review of research methods. Med Care Res Rev 2008;65:259–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.West E. Management matters: the link between hospital organisation and quality of patient care. Qual Health Care 2001;10:40–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bate P, Mendel P, Robert GB. Organizing for quality: the improvement journeys of leading hospitals in Europe and the United States. Radcliffe Publishing, 2008 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.