Abstract

Acute acalculous cholecystitis (AAC) is an inflammation of the gallbladder in the absence of demonstrated stones, which is rarely seen in paediatric population. The diagnosis is accomplished mainly through abdominal ultrasonography in the appropriate but usually non-specific clinical picture. Complicated cases need surgical intervention; the medical management is mainly constituted by supportive and antibiotic therapy, as most AAC are observed in the setting of systemic bacterial or parasitic infections. However, AAC has been rarely reported in association with Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection, where the gastrointestinal involvement is often mild and thus unrecognised. We report a case of EBV-related AAC associated with unusually severe hepatitis in an immunocompetent and otherwise healthy patient. We describe its benign clinical course, despite the serious liver impairment, by a medical management characterised by the prompt discontinuation of broad-spectrum antibiotics, as soon as EBV aetiology is ascertained, and by the appropriate analgesia and fluid resuscitation.

Background

AAC is an inflammation of the gallbladder in the absence of demonstrated stones. It represents 5–10% of all cases of acute cholecystitis in adults. Although 30–50% of cholecystitis is acalculous in paediatric population, this gallbladder disease is much less common in children compared with adults.1 AAC is usually observed in the setting of the critical disease (eg, trauma, extensive burns, postoperative, etc) or systemic bacterial and parasitic infection (eg, sepsis, typhoid fever, leptospirosis, malaria, giardiasis, etc). AAC is characterised by non-specific symptoms (eg, fever, vomiting, right-upper quadrant pain) and jaundice is present in less than a half of cases. Therefore, its recognition can be difficult, especially when the clinical picture is confounded because of the underlying disease. AAC is diagnosed through radiological tests, most frequently abdominal ultrasonography. A delay in the diagnosis of AAC can lead to complications such as gangrene, empyema and perforation of the gallbladder. These account for an increase of AAC-related morbidity and mortality rate. When the clinical course of AAC is uncomplicated and a treatable infectious cause is demonstrated, a therapy with antibiotics is often curative; otherwise, laparoscopic or open cholecystectomy constitute the treatment of choice.2 3

AAC has been rarely reported in association with viral illnesses, and only anecdotally during the course of an EBV infection. The primary EBV infection can show variable clinical expression, with frequent, and often, unrecognised gastrointestinal involvement. Particularly, an EBV hepatitis is usually mild and asymptomatic.4

We report a case of AAC associated with severe liver involvement during the course of a primary EBV infection in an immunocompetent and otherwise healthy patient.

Case presentation

A previously healthy 7-year-old girl, born in Pakistan, attended our emergency department (ED) and was admitted with a 3-day history of vomiting (day 1: 3 episodes; day 2: 4 episodes; day 3: >5 episodes), which was associated with the right upper quadrant abdominal pain and jaundice. Emesis was not associated with fever or diarrhoea. When she arrived to the paediatric ED, her general clinical conditions were stable (T 37.3°C, HR 125/min, BP 90/65 mm Hg, oxygen saturation 98%, pGCS 15), although she looked distressed. On examination, her skin and the mucosae showed moderate hypohydration, with a capillary refill time of 1 s. The most relevant finding was a palpable liver (2 cm below the costal margin) associated with tenderness on the right upper abdominal quadrant and a positive Murphy's sign. The spleen was not palpable. Cardiopulmonary and neurological examinations were unremarkable. Examination of the throat showed mild pharyngeal erythema. She did not have any superficial lymph node enlargement.

Family history was negative for genetic diseases and no close relatives had developed similar symptoms in the preceding days. She had been living in Italy for the previous year, and she or her family had not travelled abroad during this period.

Investigations

Laboratory findings confirmed the presence of jaundice (total bilirubin: 8.09 mg/dL; normal values (n.v.) 0.3–1.2), predominantly characterised by an elevated direct bilirubin (5.06 mg/dL; n.v. 0–0.2), suggesting cholestasis. Transaminases were markedly elevated: glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (aspartate aminotransferase) 3398 mU/mL (n.v. 0–35), glutamic-pyruvic transaminase (alanine aminotransferase ) 3324 mU/mL (n.v. 0–45). Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was also significantly increased (2387 mU/mL; n.v. 220–450). γ-Glutamyl transferase (γGT) showed a mild increase (143 mU/mL; n.v. 7–33). A mild impairment of liver biosynthetic function was confirmed by a rise in ammonium (109 µg/dL; n.v. 40–80) and alteration of coagulation parameters: prothrombin time (PT) 63% (n.v. 70–120%); activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) 32.4 s (n.v. 26–32); fibrinogen 230 mg/dL (n.v. 250–400). Serum albumin levels were conserved (6.9 g/dL). The blood count was normal (white cell count 8500/mm3, platelets (PLT) 293000/mm3, haemoglobin 14.1 mg/dL) as was the C reactive protein (0.35 mg/dL; n.v. 0–0.5). The urinary output was mildly impaired and the urinary dipstick was normal.

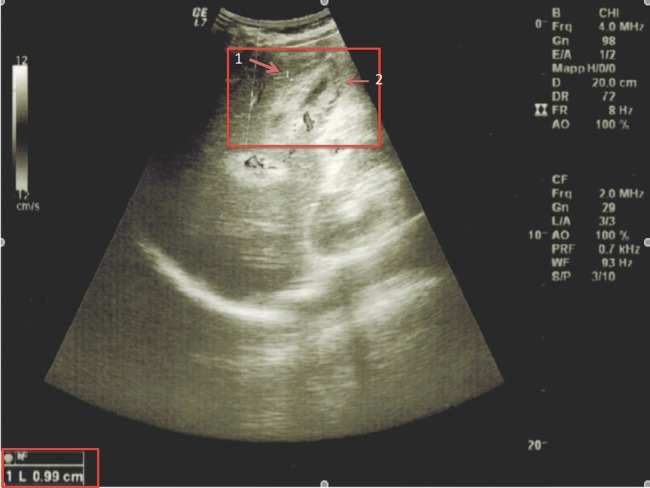

An abdominal ultrasound (US) scan showed a mild volumetric increase of the liver, which resulted in a diffusely inhomogeneous structure, but with no focal lesions. The gallbladder revealed a marked wall thickening (10 mm) with diffuse presence of mucosal thin sludge and a collection of pericolecystic fluid (figure 1). However, no gallstones were present inside and there was no dilation of the biliary tract. The spleen was normal.

Figure 1.

Abdominal ultrasound image showing the gallbladder at the onset of acute acalculous cholecystitis: it is characterised by a marked wall thickening up to 0.99 cm (1), diffuse presence of mucosal thin sludge and collection of pericolecystic fluid (2).

Serological tests ruled out hepatitis A, B and C, but showed positivity of IgM (119 U/mL) and IgG (>750 U/mL) antibodies against EBV capsid antigen (VCA). IgG antibodies for EBV nuclear antigen (EBNA) resulted negative. Anti-cytomegalovirus (CMV) IgGs were positive (2.6 UI/mL) as were anti-CMV IgMs, although at low levels (27 UI/mL), that were interpreted as artifactual since plasma CMV-DNA was negative by PCR. Blood and urine cultures were negative. Other causes of liver disease were excluded (negative serological screening for coeliac disease, anti-nucleus antobodies (ANA), anti-mithocondrial antibodies (AMA), anti liver kidney microsomal antibodies (LKM), anti-smooth muscle antibodies (ASMA); normal levels of ceruloplasmin and α1-antitrypsin). A diagnosis of ACC, associated with severe hepatitis caused by primary EBV infection, was made.

Treatment

The initial clinical management consisted of fluid resuscitation with glucose and electrolyte solutions, and broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy with a third-generation cephalosporin (cefotaxime: 100 mg/kg/die) until the viral aetiology of the clinical condition was ascertained. As the patient reported of significant pain, she was treated with ketorolac at a reduced dose because of the liver disease (0.2–0.3 mg/kg, twice a day). No surgical approach was sought, as the ACC was not complicated and the patient's clinical conditions were stable.

Outcome and follow-up

In the first 2–3 days after admission, bilirubin plasma level peaked at 11.42 mg/dL. During this period, coagulation parameters got mildly worse (PT 53%, aPTT 36.4 s, fibrinogen 174 mg/dL) and therefore the patient received a single dose of vitamin K1 intramuscular. (10 mg). C reactive protein was always normal. Liver function started showing some improvement, and the subsequent clinical course was uneventful. The patient was discharged on day 9 after admission. At that time, the biochemical parameters were improved (bilirubin 3.48 mg/dL, GOT 72 mU/mL, GPT 242 mU/mL, LDH 354 UI/L, γGT 55 UI/L) and the abdominal US showed a reduction of liver size with a more homogeneous parenchyma. The thickness of the gallbladder wall was normalised (3 mm) without evidence of liquid sludge. During the subsequent 12- month follow-up, the patient remained in a good clinical condition and the biochemical and US parameters all returned to normal.

Discussion

We describe the clinical case of a child affected by severe acute hepatitis associated with AAC, which is very unusual in the setting of primary EBV disease.

EBV is ubiquitous worldwide and most of the infections, which are acquired during childhood, are asymptomatic. In the remaining cases, the most common clinical picture is referred to as infectious mononucleosis, characterised by fever, sore throat, lymph node enlargement and presence of atypical lymphocytes in the peripheral blood smear. Gastrointestinal manifestations and specifically liver involvement are frequent but usually benign so that they are often unrecognised. Indeed, a mild increase of liver enzymes and abdominal pain is usually noted in around 80% of cases. Conversely, jaundice and hepatitis with moderate-severe alteration of plasma liver enzymes (defined by more than 10 times normal values) are described in less than 5% of symptomatic EBV infections.4 5

In a retrospective series of 1995 consecutive adult patients with jaundice and hepatitis, Vine et al recently showed that EBV was involved in only 0.85% of cases and the worst increase of liver enzymes did not exceed 1400 U/L, with a median peak of plasma bilirubin around 5 mg/dL. More profound impairment of liver enzymes and biosynthetic function (bilirubin, serum albumin and coagulation profile) usually suggests other causes, such as infections by classical hepatitis viruses or drug toxicity. Indeed, severe liver injury during EBV infection is very rare and is mostly reported in the post-transplant and immunodeficiency settings.6 In otherwise healthy and immunocompetent children, severe EBV hepatitis is exceedingly rare. The worst case of severe EBV hepatitis in an immunocompetent host was described by Kimura et al in a 1-year-old girl, whose liver enzymes in the blood peaked at ∼2000 U/L; moreover, bilirubin plasma level exceeded 10 mg/dL and liver protein synthesis was impaired.7

It is known that EBV mainly targets B lymphocytes, and more than 90% of people carry the virus as lifelong and latent form inside this cell type. Nevertheless, some authors showed how EBV could infect T cells, which showed proliferating and liver-infiltrating capabilities.6 Hara et al8 speculated that the genetic background of the patient might affect the pattern of cell infection by the virus, hypothesising that people from East Asia could be more susceptible to EBV-associated severe diseases. Their paper suggests that in severe forms of EBV infection in previously healthy hosts, and particularly in cases of jaundiced hepatitis, EBV seems to infect mainly T cells.

In addition to a severe form of EBV liver disease, our patient also developed AAC. Cholestasis is a common feature of EBV hepatitis, but the coexistence of AAC has rarely been described. In our knowledge, only four cases of EBV-associated AAC have been reported in medical literature, but the first practical description is demonstrated through our patient, where such a rare disease in childhood occurred along with a severe form of EBV hepatitis.9 10

The clinical symptoms of AAC are mainly represented by fever, vomiting and right-upper-quadrant pain; jaundice is not always present. Therefore, diagnosis can be challenging especially in the setting of an underlying severe viral hepatitis, whose clinical findings are overlapping.3 Abdominal US is considered as an effective tool to pursue the diagnosis of AAC. The main US diagnostic criteria supporting AAC are the absence of gallstones in the gallbladder, in addition to at least of two of the following findings: increased wall thickness >3.5–4 mm, pericholecystic fluid and mucosal membrane sludge.3 In our patient, the gallbladder had a 10 mm wall thickening with the presence of some sludge inside and pericholecystic fluid all around. Our patient closely matched the echographic diagnostic criteria, and the clinical finding of a positive Murphy's further suggested that she indeed presented with AAC in the context of a severe EBV-associated hepatitis.

Most of the papers report the administration of broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy as an appropriate medical management in all cases of AAC, since they can evolve to complications such as gangrene, empyema and perforation of the gallbladder, which are associated with an increased morbidity and mortality.2 10 Following these recommendations, we started antibiotic treatment with cefotaxime for 2 days, pending the microbiological tests, but this was interrupted as soon as EBV aetiology was ascertained and sepsis was excluded. As expected, despite the patient's general status was complicated by a severe liver hepatitis, AAC did not request any surgical intervention, which is usually recommended in complicated forms or patients not responding to the medical therapy. Consequently, the patient underwent a close clinical and laboratory monitoring and the resolution of AAC was documented by an abdominal US follow-up.

In our case, we were able to demonstrate a complete clinical and radiological resolution of AAC only after a supportive and analgesic therapy. Therefore, we believe that antibiotic therapy could be avoided when clinical and diagnostic findings are consistent with a viral illness. Moreover, we also describe the off-label use of ketorolac in a patient younger than 16 years (at half of the recommended dosage based on body weight), without evidence of any significant adverse reaction, despite the initial significant liver impairment. Our report confirms the good clinical course and the self-limiting nature of a primary EBV infection in an immunocompetent host, even in the presence of severe hepatitis associated with AAC.

Learning points.

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-related acute acalculous cholecystitis (AAC) requires an abdominal ultrasound follow-up to document its complete resolution.

As soon as there is evidence that AAC is caused by EBV or other viral agents, antibiotic therapy can be safely discontinued.

AAC-related pain has been safely treated by adjusted dosage of ketorolac, despite the significant impairment of the liver function.

Footnotes

Contributors: DP contributed to the conception and design of the article and drafted the manuscript. GC and NM contributed to the acquisition and interpretation of data. PB contributed in revising critically the manuscript and provided important intellectual contributions.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Prashanth GP, Angadi BH, Joshi SN, et al. Unusual cause of abdominal pain in pediatric emergency medicine. Pediatr Emer Care 2012;28:560–1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsakayannis DE, Kozakewich HPV, Lillehei CW. Acalculous cholecystitis in children. J Pediatr Surg 1996;31:127–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huffman JL, Schenker S. Acute acalculous cholecystitis: a review. Clin Gastroent Hepatol 2010;8:15–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Attilakos A, Prassouli A, Hadjigeorgiou G, et al. Acute acalculous cholecystitis in children with Epstein-Barr virus infection: a role for Gilbert's syndrome? Int J Infect Dis 2009;13:e161–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crum NF. Epstein Barr virus hepatitis: case series and review. South Med J 2006;99:544–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vine LJ, Shepherd K, Hunter JC, et al. Characteristics of Epstein-Barr virus hepatitis among patients with jaundice or acute hepatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2012;36:16–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kimura H, Nagasaka T, Hoshino Y, et al. Severe hepatitis caused by Epstein-Barr virus without infection of hepatocytes. Hum Pathol 2001;32:757–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hara S, Hoshino Y, Naitou T, et al. Association of virus infected T cell in severe hepatitis caused by primary Epstein-Barr virus infection. J Clin Virol 2006;35:250–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iaria C, Arena L, Di Maio G, et al. Acute acalculous cholecystitis during the course of primary Epstein-Barr virus infection: a new case and a review of literature. Int J Infect Dis 2008;12:391–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gora-Gebka M, Liberek A, Bako W, et al. Acute acalculous cholecystitis of viral etiology: a rare condition in children? J Pediatr Surg 2008;43:e25–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]