Abstract

Objectives

We aimed to examine staff members’ perceptions of communication within and between different professions, safety attitudes and psychological empowerment, prior to and after implementation of the communication tool Situation-Background-Assessment-Recommendation (SBAR) at an anaesthetic clinic. The aim was also to study whether there was any change in the proportion of incident reports caused by communication errors.

Design

A prospective intervention study with comparison group using preassessments and postassessments. Questionnaire data were collected from staff in an intervention (n=100) and a comparison group (n=69) at the anaesthetic clinic in two hospitals prior to (2011) and after (2012) implementation of SBAR. The proportion of incident reports due to communication errors was calculated during a 1-year period prior to and after implementation.

Setting

Anaesthetic clinics at two hospitals in Sweden.

Participants

All licensed practical nurses, registered nurses and physicians working in the operating theatres, intensive care units and postanaesthesia care units at anaesthetic clinics in two hospitals were invited to participate.

Intervention

Implementation of SBAR in an anaesthetic clinic.

Primary and secondary outcomes

The primary outcomes were staff members’ perception of communication within and between different professions, as well as their perceptions of safety attitudes. Secondary outcomes were psychological empowerment and incident reports due to error of communication.

Results

In the intervention group, there were statistically significant improvements in the factors ‘Between-group communication accuracy’ (p=0.039) and ‘Safety climate’ (p=0.011). The proportion of incident reports due to communication errors decreased significantly (p<0.0001) in the intervention group, from 31% to 11%.

Conclusions

Implementing the communication tool SBAR in anaesthetic clinics was associated with improvement in staff members’ perception of communication between professionals and their perception of the safety climate as well as with a decreased proportion of incident reports related to communication errors.

Trial registration

ISRCTN37251313.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Despite recommendation of implementing Situation-Background-Assessment-Recommendation in healthcare, there are a few intervention studies with a comparison group, using preassessments and postassessments, evaluating staff members’ perception of communication and safety attitudes as well as incident reports due to communication errors, thus the study adds new knowledge to the subject area.

The implementation was followed by the authors using manipulation check, involving randomised structured telephone interviews. To monitor the implementation, the local interprofessional workgroup conducted observations of handovers.

The response rate was satisfying, exceeding 70% at baseline and follow-up in the two groups.

The very natures of the quasi-experimental design entail selection biases as the lack of randomisation.

Introduction

Teamwork in operating theatres and intensive care units (ICUs) requires straightforward, clear and consistent communication as well as good collaboration. Nonetheless, communication breakdowns are frequent during the preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative periods.1 2 Communication and collaboration problems, in turn, have been shown to be the strongest predictors of health-related harm.2–4 The communication tool Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendations (SBAR) is used in high-risk organisations to make communication more effective and consistent, and it has also been introduced in healthcare. SBAR is thought to create conditions for accurate information exchange and encourage dialogue, and the WHO recommends using it in healthcare to increase patient safety.5 Using the communication tool SBAR, important information can be transferred in a brief and concise manner, and in a predictable structure.6 In a review7 investigating studies on communication failures and how to avoid them, the authors suggested that one way to improve communication is to structure the information by employing tools such as SBAR.

Studies evaluating SBAR have been conducted in the USA,8–10 Canada,11 12 Australia,13 14 the UK,15 Belgium16 and the Netherlands.17 The results have shown an improved collaboration and nurse–physician communication, as perceived by nurses working in surgical and medical wards.16 Other studies have shown improvements in team communication and the safety culture, as assessed by rehabilitation staff.11 12 However, low adherence to SBAR was found in a simulation study among nurses working in surgical and medical wards 1 year after implementation.17 Still another study found, in contrast, that about 60% of nurses reported using SBAR.9 Findings from studies of simulated telephone referrals made by medical students and junior doctors have shown improved communication14 and improved call impact as measured by an observer when SBAR was used.13 Studies measuring clinical outcomes have found a reduced unexpected death,16 a decreased order entry errors10 and improvements in safety reporting11 after implementation of SBAR. Among the studies aforementioned, we found only six that have used a comparison group,10–14 17 and of these, three were simulation studies.13 14 17 One review18 studying interventions intended to facilitate teamwork and communication in healthcare found that only 3 of 14 studies measured clinical outcomes and that only 7 of 14 studies measured effects on the safety culture.18 Thus, there is a need to further investigate staff and clinical outcomes with regard to use of the communication tool SBAR.

The aim of the present study was to examine staff members’ perceptions of communication within and between different professions, as well as their safety attitudes and psychological empowerment, prior to and after implementation of the communication tool SBAR at an anaesthetic clinic. A further aim was to investigate whether there were any differences in change over time in these variables between an intervention group that was introduced to SBAR and a comparison group. Still another aim was to study whether there was any change in the proportion of incident reports due to communication errors. We hypothesised that implementation of the communication tool SBAR would improve staff members’ perception of communication within and between different professions as well as their safety attitudes, thereby decreasing reports of incidents caused by communication errors as well as increasing staff members’ perception of psychological empowerment.

Method

Design

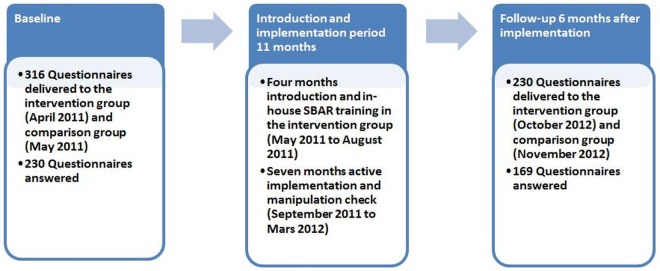

A prospective intervention study with comparison group using preassessments and postassessments was used. The study involved one intervention group in which the SBAR was implemented (staff at an anaesthetic clinic at one hospital) and one comparison group (staff at another hospital's anaesthetic clinic). Questionnaires were delivered at baseline and at follow-up 6 months after implementation, and the proportion of incident reports at the two hospitals was measured during a 1-year period prior to and after implementation (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Outline of design (SBAR, Situation-Background-Assessment-Recommendation).

Sample and procedures

A total of 316 questionnaires, and 2 reminders, were delivered to all staff (licensed practical nurses (LPNs), registered nurses and physicians) working in the operating theatres, ICUs and postanaesthesia care unit at anaesthetic clinics in the two hospitals during spring 2011. The two hospitals were located in the same county council and thus the clinics shared the same top management.

Intervention

The decision to implement the communication tool SBAR at the clinic was taken by the management. Strategies to facilitate the implementation were: modifying a SBAR card, in-house training course, information material and observations during 7 months of the implementation period. A pocket SBAR card was slightly modified prior to implementation by a local interprofessional workgroup to adapt it to needs at the clinic. The intervention included an in-house training course (2.5 h of instruction and role playing) and implementation of the communication tool SBAR. During the introduction period May to September 2011, 155 of 194 (80%) staff were trained and the rest were offered continuous training. Informational material describing SBAR was distributed to all staff in the intervention group, who received the pocket card describing the SBAR structure to be used. At the postanaesthesia care unit, the SBAR card was also attached to the patients’ tables, where most handovers were conducted, and on the wall in the room where the physician's handovers were conducted. At the ICU, a printed SBAR template was used for the receiver's notes during handovers. All staff members in the intervention group were encouraged to take part in the training course and to use the communication tool SBAR in their daily work. The period with an in-house training course was followed by a 7-month monitoring period, which consisted of 168 structured observations of handovers carried out by four members of the local interprofessional workgroup. The observations were used by management to monitor the intervention process and as a feedback to the intervention group. In the comparison group, no structured communication system was used.

Manipulation check

A careful control of the implementation is required for interpretation of the findings.19 To check whether SBAR was implemented as intended, measures were made during a 7-month period to follow the implementation. In the intervention group, structured telephone interviews were conducted by one author (MR) with a random sample of 10 staff each month, except for 1 month when only 6 staff members were reached. In total, 11 physicians, 17 intensive care nurses, 10 anaesthesia nurse, 8 operating theatre nurses and 20 LPNs were interviewed. Results showed that the majority of staff had taken the in-house training course and had used the SBAR tool during the past seven working days.

Data collection

Questionnaire data were collected prior to implementation of SBAR in April 2011 and at follow-up 6 months after completion of the implementation period in October 2012. To measure communication within and between different professions, the ICU Nurse–Physician Questionnaire20 was used, and the Safety Attitudes Questionnaire (SAQ)21 was used to measure staff members’ attitudes towards six patient-safety-related domains. Spritzer's empowerment scale22 was used to measure psychological empowerment. Incident reports were collected from the hospitals’ registration systems during a 1-year period prior to (1 April 2010 to 31 March 2011) and after implementation of SBAR (1 April 2012 to 31 March 2013).

Primary outcome measures

The ICU Nurse–Physician Questionnaire (short version, section 1)23 consists of five factors: within-group communication openness (4 items); between-group communication openness (4 items); within-group communication accuracy (4 items); between-group communication accuracy (3 items) and communication timeliness (3 items). The original questionnaire was created to address the relationship between nurses and physicians only, but because LPNs are a common staff group in Sweden, the questionnaire was adapted for LPNs and thus to suite Swedish working conditions. The term within-group communication means communication within the same profession (eg, physician's perception of communicating with physicians) and the term between-group communication means, for example, physician's perception of communicating with nurses and physician's perception of communicating with LPNs and so on. The items are answered in a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘Strongly Disagree’ to ‘Strongly Agree.’ Negatively worded items are reversed before factor scores are averaged. The ICU Nurse–Physician Questionnaire has shown satisfactory psychometric properties. Cronbach's α values (α) for the five factors have been 0.64–0.88.20 Translation of the questionnaire was conducted forward by the research team and back-translation was carried out by a bilingual translator.24 In the present study, α values were between 0.68 and 0.88 at baseline and 0.68 and 0.85 at follow-up (table 1).

Table 1.

Staff members’ assessment of communication within and between groups, safety attitudes and empowerment in the intervention and comparison group at baseline and follow-up as change over time between groups

| Intervention group–within group | Comparison group–within group | Change over time between groups | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement factors | Cronbach's α | Mean value (SD)* | p Value* | Mean value (SD)* | p Value* | p Value† |

| ICU Nurse–Physician Questionnaire | ||||||

| Within-group communication openness | ||||||

| Baseline | 0.80 | 4.3 (0.6) | 4.4 (0.6) | |||

| Follow-up | 0.78 | 4.3 (0.5) | 0.998 | 4.4 (0.5) | 0.529 | 0.390 |

| Between-group communication openness | ||||||

| Baseline | ||||||

| Physician↔RN; LPN↔Physician; RN↔LPN |

0.82 0.88 0.84 |

4.3 (0.5) | 4.2 (0.6) | |||

| Follow-up | ||||||

| Physician↔RN; LPN↔Physician; RN↔LPN |

0.85 0.84 0.82 |

4.3 (0.5) | 0.686 | 4.3 (0.6) | 0.039 | 0.263 |

| Within-group communication accuracy | ||||||

| Baseline | 0.73 | 3.3 (0.8) | 3.7 (0.8) | |||

| Follow-up | 0.75 | 3.4 (0.8) | 0.076 | 3.7 (0.9) | 0.966 | 0.371 |

| Between-group communication accuracy | ||||||

| Baseline | ||||||

| Physician↔RN; LPN↔Physician; RN↔LPN |

0.69 0.68 0.77 |

3.3 (0.8) | 3.5 (0.8) | |||

| Follow-up | ||||||

| Physician↔RN; LPN↔Physician; RN↔LPN |

0.77 0.69 0.76 |

3.5 (0.8) | 0.001 | 3.6 (0.8) | 0.185 | 0.172 |

| Communication timeliness | ||||||

| Baseline | 0.74 | 4.2 (0.7) | 4.2 (0.7) | |||

| Follow-up | 0.68 | 4.3 (0.6) | 0.612 | 4.3 (0.7) | 0.650 | 0.958 |

| Safety Attitudes Questionnaire | ||||||

| Teamwork climate | ||||||

| Baseline | 0.73 | 72.2 (15.1) | 76.9 (15.1) | |||

| Follow-up | 0.74 | 73.8 (14.4) | 0.350 | 76.7 (15.8) | 0.914 | 0.584 |

| Safety climate | ||||||

| Baseline | 0.76 | 63.1 (15.8) | 70.3 (14.3) | |||

| Follow-up | 0.78 | 66.4 (16.2) | 0.011 | 70.2 (16.0) | 0.949 | 0.087 |

| Job satisfaction | ||||||

| Baseline | 0.85 | 75.3 (15.5) | 81.5 (16.4) | |||

| Follow-up | 0.86 | 74.2 (15.4) | 0.604 | 81.7 (15.0) | 0.865 | 0.771 |

| Stress recognition | ||||||

| Baseline | 0.85 | 68.0 (21.9) | 65.8 (25.2) | |||

| Follow-up | 0.82 | 67.8 (20.8) | 0.483 | 63.5 (24.9) | 0.382 | 0.388 |

| Perception of management unit | ||||||

| Baseline | 0.76 | 60.2 (17.9) | 59.2 (16.7) | |||

| Follow-up | 0.80 | 60.2 (18.6) | 0.667 | 68.6 (16.7) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Working condition | ||||||

| Baseline | 0.71 | 63.9 (19.2) | 73.3 (15.6) | |||

| Follow-up | 0.71 | 63.5 (18.8) | 0.956 | 77.8 (16.2) | 0.029 | 0.131 |

| Spreitzer's Empowerment scale | ||||||

| Meaning | ||||||

| Baseline | 0.86 | 6.2 (0.8) | 6.3 (0.9) | |||

| Follow-up | 0.86 | 6.3 (0.7) | 0.270 | 6.3 (0.8) | 0.935 | 0.602 |

| Competence | ||||||

| Baseline | 0.86 | 6.4 (0.7) | 6.5 (0.6) | |||

| Follow-up | 0.80 | 6.4 (0.6) | 0.985 | 6.5 (0.7) | 0.877 | 0.818 |

| Self-determination | ||||||

| Baseline | 0.86 | 4.3 (1.2) | 4.4 (1.5) | |||

| Follow-up | 0.86 | 4.3 (1.3) | 0.992 | 4.6 (1.3) | 0.342 | 0.465 |

| Impact | ||||||

| Baseline | 0.88 | 4.2 (1.3) | 4.5 (1.4) | |||

| Follow-up | 0.87 | 4.2 (1.4) | 0.639 | 4.5 (1.3) | 0.867 | 0.857 |

| Empowerment total factors | ||||||

| Baseline | 0.85 | 5.3 (0.7) | 5.4 (0.8) | |||

| Follow-up | 0.86 | 5.3 (0.8) | 0.474 | 5.5 (0.7) | 0.444 | 0.916 |

Mean and SD n=169.

*Wilcoxon signed rank test

†Mann-Whitney U test. The significant level is 0.05 and statistical significant results are marked with boldface text.

LPN, licenced practical nurse; RN, registered nurse.

The SAQ (short form)21 consists of six factors: teamwork climate (6 items); safety climate (7 items); job satisfaction (5 items); stress recognition (4 items); perceptions of management (6 items) and working conditions (3 items). The items are answered in a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘Disagree Strongly’ to ‘Agree Strongly.’ The negatively worded items are reversed and the scale was converted to a 0–100% scale, where 0%=disagree strongly, 25%=disagree slightly, 50%=neutral, 75%=agree slightly and 100%=agree strongly. The SAQ has shown satisfactory psychometric properties. Cronbach's α values have been between 0.70 and 0.85 for the factors.21 Translation of the questionnaire was conducted forward by the research team and back-translation was carried out by a bilingual translator.24 In the present study, α values ranged from 0.71 to 0.85 at baseline and from 0.71 to 0.86 at follow-up for the factors (table 1).

Secondary outcome measures

Spreitzer's empowerment scale25 consists of four factors: meaning (3 items); competence (3 items); self-determination (3 items) and impact (3 items). The items are answered on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree.’ Factor scores and the total scale are averaged. The Swedish version of the scale has shown satisfactory psychometric properties, with α values ranging from 0.77 to 0.90.22 In the present study, α values ranged from 0.85 to 0.88 at baseline and from 0.80 to 0.87 at follow-up for the factors (table 1).

The number of incident reports was measured during a 1-year period prior to implementation (1 April 2010 to 31 March 2011) and after implementation of SBAR (1 April 2012 to 31 March 2013). In accordance with WHO definitions,26 we defined incident reports as “A process used to document occurrences that are not consistent with routine hospital operation or patient care.” A communication error is defined as “Missing or wrong information exchange or misinterpretation or misunderstanding.”26 In the county council where the present study was conducted, the clinic administrator has overall responsibility for incident reports. The incident reports are examined by an investigator who reviewed the cause of the incident and what measures were taken. The result of the investigation then goes back to the clinic, where possible follow-ups are carried out.

Data analysis

The data were analysed using descriptive statistics such as means, SDs, absolute numbers and percentages. For within-group comparisons over time, the Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test was used, and for between-group comparisons, the Mann-Whitney U test was used. The χ2 and Fisher's exact test were used to detect differences in the frequency data. Factor scores in the three questionnaires were calculated if at least 66.7% of the questions for each factor were answered. Internal consistency was calculated using Cronbach's α. Non-parametric tests were used because the majority of factors did not have a normal distribution. The level for statistical significance was set at p<0.05 (two-tailed).

Ethical considerations

All participants received written information about the study aim and procedures and were told that participation was strictly voluntary and could be discontinued at any time without explanation.

Results

Sample characteristics

The response rate at baseline was 72% (n=139 of 194) in the intervention group and 75% (n=91 of 122) in the comparison group. The response rate at follow-up in 2012 was 72% (n=100 of 139) and 76% (n=69 of 91), respectively (table 2). The dropouts had fewer years working in the profession (p=0.005) fewer years working at the clinic (p<0.001) and higher scores on the factor teamwork climate (p=0.017) and lower scores on the factor competence (p=0.048) than the participants did. There were no statistically significant differences between the intervention and comparison groups at baseline regarding age, sex, working years in the profession, working years at the clinic and working time (table 3). However, at baseline, there were statistically significant higher scores in the comparison group on five factors; teamwork climate (p=0.045), safety climate (p=0.002), job satisfaction (p=0.004), working condition (p=0.002) and within-group communication accuracy (p=0.001).

Table 2.

Reasons for non-participants/dropouts at baseline and follow-up

| Dropout | Intervention group | Comparison group |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 194 | 122 |

| Refusal | 3 | 24 |

| No reason | 52 | 7 |

| Answered questionnaires | 139 | 91 |

| Follow-up | 139 | 91 |

| Parental leave | 3 | 2 |

| Changed workplace | 3 | 1 |

| Long-term illness | – | 1 |

| Retired | 1 | 1 |

| Quit work | 3 | 6 |

| Leave of absence | 5 | 1 |

| Education | 2 | 1 |

| Total unavailable staff | 17 | 13 |

| Eligible staff | 122 | 78 |

| Refusal | 6 | 6 |

| No reason | 16 | 3 |

| Answered questionnaires | 100 | 69 |

Table 3.

Demographic data on staff members in the intervention group and control group who participated at baseline and follow-up

| Intervention group (n=100) | Comparison group (n=69) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, m (SD) | 48.2 (8.7) | 48.6 (9.0) | 0.780 |

| Sex male/female, n | 15 (15%)/85 (85%) | 11 (16%)/58 (84%) | 1.000 |

| Profession, n | 0.945 | ||

| LPN | 27 (27%) | 18 (26%) | |

| RN | 63 (63%) | 43 (62%) | |

| Physician | 10 (10%) | 8 (12%) | |

| Years in the profession, m (SD) | 17.5 (11.2) | 19.5 (10.2) | 0.257 |

| Years at the clinic, m (SD) | 15.2 (11.0) | 15.4 (10.3) | 0.883 |

| Working full-time/part-time, n | 60 (60%)/40 (40%) | 48 (70%)/21 (30%) | 0.254 |

Independent samples t test and χ2 test. The significant level is 0.05.

LPN, licensed practical nurse; m, mean; RN, registered nurse.

Primary outcome

Of the five factors in the ICU Nurse–Physician Questionnaire, the factor between-group communication accuracy improved significantly (p=0.001) over time in the intervention group. For the factor within-group communication accuracy, there was a tendency for improvement over time in the intervention group, though it was not statistically significant (p=0.076). This finding required further investigation, and we proceeded by analysing each item. There was a significant improvement over time for the item “It is often necessary for me to go back and check the accuracy of information I have received from [physicians, nurses or licensed practical nurses] in this unit” (p=0.025). In the comparison group, the factor between-group openness improved significantly (p=0.039) over time. When changes over time were compared between the intervention group and comparison group, the results showed no statistically significant differences (table 1). Of the factors in the SAQ, the factor safety climate improved significantly (p=0.011) over time in the intervention group. For the other factors in the SAQ, there were no statistically significant differences. In the comparison group, the factor perception of management at the unit showed a significant (p<0.001) improvement over time, as did the factor working condition (p=0.029). When changes over time were compared between the intervention group and comparison group, the results showed a significant difference (p<0.001) between groups for the factor perception of management at the unit. For the factor safety climate, the p value was 0.087 when change over time between the groups was compared (table 1).

Secondary outcome

In the intervention group, the number of incident reports during a 1-year period prior to implementation was 116, where 36 (31%) were due to communication errors. The same year, in the comparison group, 6 of the 24 (25%) registered incident reports were due to communication errors. In the intervention group, during a 1-year period after implementation, the incident reports due to communication errors had decreased to 23 of a total of 208 (11%). During the same period in the comparison group, the number of incident reports due to communication errors was 6 of 32 (19%). The decrease in the proportions of incident reports due to communication errors in the intervention group was statistically significant (p<0.0001), though it was not in the comparison group (p=0.744). Regarding psychological empowerment, the results revealed no statistically significant changes over time in either the intervention group or the comparison group (table 1).

Discussion

SBAR is thought to facilitate communication between professions and increase safety as well as to decrease the negative effects the professional hierarchy may have on communication. Our results showed that implementation of the communication tool SBAR resulted in significant improvement over time in staff members’ perceptions of between-group communication accuracy and safety climate as well as a tendency towards improvement in within-group communication accuracy. Furthermore, the proportion of incident reports due to communication errors decreased significantly, from 31% (36 of 116) to 11% (23 of 208), in the intervention group compared with a non-significant decrease, from 25% (6 of 24) to 19% (6 of 32), in the comparison group. Thus, in the intervention group, safety reporting seemed to improve but the proportion of incident reports due to communication decreased significantly.

The improvement in staff members’ perceptions of between-group communication accuracy after implementation of the communication tool SBAR seen in the present study is similar to findings from a study by De Meester et al,16 where nurse–physician communication also improved. In a study by Manojlovich and DeCicco,27 between-group communication was shown to be a significant predictor of perceived medication error.27 Nurses and physicians are trained to express themselves in different ways,28 and communication between different professions is known to be a contributing factor in surgical malpractice claims.1 As staff members’ perceptions of between-group communication accuracy improved, it would seem that SBAR was able to bridge differences in style of communication.

Safety climate also improved, and the proportion of incident reports due to communication errors decreased in the intervention group, which may indicate that safety performance improved. One study29 of 91 hospitals found that a higher level of safety climate was associated with higher safety performance at the hospital level. Furthermore, Huang et al30 studied 30 ICUs in the USA using SAQ and found that lower safety climate was associated with patient outcomes such as increased hospital length of stay. However, another study by Rosen et al31 failed to show a relationship between safety climate and hospital safety performance. As in the present study, improved perception of safety climate has also been found in studies11 12 of rehabilitation settings in which SBAR had been implemented. Verbal communication errors were found to be an important cause of severe patient safety incidents.32 In the present study, there was a decrease in the proportion of incident reports due to communication errors. According to the present results, one can assume that SBAR made communication safer, resulting in a decrease in incident reports due to communication errors. This interpretation is also in line with our hypothesis. We also hypothesised that a secondary outcome of implementing SBAR could be an increase in staff members’ perception of psychological empowerment. In the present study, it would seem reasonable to assume that SBAR training should have increased staff members’ empowerment, but no such effect was found during the study period.

In the comparison group, there were no significant changes in staff members’ perceptions of communication accuracy or safety climate. However, the factors between-group communication openness, perception of management at the unit and working condition improved significantly over time. During the period between baseline and follow-up, there were work-related changes in the comparison group that may have affected the results. The staff in the operating theatre had increased in size, and there had been discussions of the importance of collaboration at the ICU. When working condition is improved one can expect that communication also improves.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

The strengths of the present study were that measures of safety culture and the number of incident reports related to communication were included, as previously recommended,18 and that a comparison group was used. Furthermore, during 7 months of the implementation period, we followed the implementation using a manipulation check involving randomised structured telephone interviews. An additional support in the implementation was observations of handovers conducted by the local interprofessional workgroup. In a simulation study, low adherence was found for use of SBAR during a 1-year period after implementation in a hospital.17 In the present study, the manipulation check and observations showed that SBAR was in use at the clinic. One other strength is that the questionnaires used have shown satisfactory psychometric properties, and Cronbach's α values in the present study for all instruments, total scale and factors were over 0.68. Although the two groups were different in size, there were no significant differences in the demographic data. The distribution was not normal and a limitation was that it was not possible to carry out multivariate analysis to correct for the differences at baseline in some variables as ‘between-group communication openness’, ‘perception of management unit’ and ‘working conditions’. The response rate was satisfying, exceeding 70% at baseline and follow-up in the two groups. When interpreting the present results, possible threats to internal validity should be considered. First, the very nature of the quasi-experimental design entailed selection biases: the participants were not randomly assigned and there were statistically significant differences between the intervention group and the comparison group at baseline. Although the comparison group had higher baseline levels on the five factors that could have affected the results, there was still room for improvement. Second, the loss of subjects poses another threat to internal validity, in that the dropouts had statistically higher scores on the factor Teamwork climate and statistically lower scores on the factor Competence than the participants did. On the other hand, the number of dropouts was moderate. There were also differences in incident reporting. The comparison group had an overall lower frequency of registered incident reports. There may be several reasons for this, for example, that the frequency of incidents was actually different or that there was a difference in the tendency to report incidents. Third, an additional threat to internal validity was that there may have been some diffusion of the intervention to the comparison group, which could have affected the results. Further research dealing with these methodological issues is needed to confirm our results.

Conclusion

Implementing the communication tool SBAR in anaesthetic care can improve communication between professionals, improve the safety climate and reduce incidents caused by communication errors.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors (MR, GM, CLS and ME) contributed to the design, interpreted data, drafted and revised the article critically. Data analysis was conducted by MR and ME. MR collected data, conducted the manipulation check and wrote the manuscript under the supervision of GM, CLS and ME. All authors read and approved the final version of the article.

Funding: This work was supported by the Faculty of Health and Occupational Studies, University of Gävle and by the County Council Gävleborg. It was also supported by the Patient Insurance LÖF and the Swedish Society of Nursing, but these organisations had no role in the design and running of the study.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The Regional Ethical Review Board (reg. no. 2011/061).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Greenberg CC, Regenbogen SE, Studdert DM, et al. Patterns of communication breakdowns resulting in injury to surgical patients . J Am Coll Surg 2007;204:533–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lingard L, Espin S, Whyte S, et al. Communication failures in the operating room: an observational classification of recurrent types and effects . Qual Saf Health Care 2004;13:330–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wiegmann DA, ElBardissi AW, Dearani JA, et al. Disruptions in surgical flow and their relationship to surgical errors: an exploratory investigation . Surgery 2007;142:658–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White AA, Pichert JW, Bledsoe SH, et al. Cause and effect analysis of closed claims in obstetrics and gynecology . Obstet Gynecol 2005;105:1031–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO Patient Safety Solutions| volume 1, solution 3 | May 2007. http://www.refworks.com/refgrabit/rw2linkpage.aspx?subscriber=6107&user=1209&_=1344860455630 (accessed 13 Aug 2012).

- 6.Leonard M, Graham S, Bonacum D. The human factor: the critical importance of effective teamwork and communication in providing safe care . Qual Saf Health Care 2004;13(Suppl 1):i85–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flemming D, Hubner U. How to improve change of shift handovers and collaborative grounding and what role does the electronic patient record system play? Results of a systematic literature review. Int J Med Inform 2013;82:580–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Renz SM, Boltz MP, Wagner LM, et al. Examining the feasibility and utility of an SBAR protocol in long-term care . Geriatr Nurs 2013;34:295–301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Compton J, Copeland K, Flanders S, et al. Implementing SBAR across a large multihospital health system . Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2012;38:261–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Telem DA, Buch KE, Ellis S, et al. Integration of a formalized handoff system into the surgical curriculum: resident perspectives and early results . Arch Surg 2011;146:89–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Velji K, Baker GR, Fancott C, et al. Effectiveness of an adapted SBAR communication tool for a rehabilitation setting . Healthc Q 2008;11:72–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andreoli A, Fancott C, Velji K, et al. Using SBAR to communicate falls risk and management in inter-professional rehabilitation teams . Healthc Q 2010;13:94–101 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cunningham NJ, Weiland TJ, van Dijk J, et al. Telephone referrals by junior doctors: a randomised controlled trial assessing the impact of SBAR in a simulated setting . Postgrad Med J 2012;88:619–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marshall S, Harrison J, Flanagan B. The teaching of a structured tool improves the clarity and content of interprofessional clinical communication . Qual Saf Health Care 2009;18:137–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Christie P, Robinson H. Using a communication framework at handover to boost patient outcomes . Nurs Times 2009;105:13–15 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Meester K, Verspuy M, Monsieurs KG, et al. SBAR improves nurse-physician communication and reduces unexpected death: a pre and post intervention study . Resuscitation 2013;84:1192–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ludikhuize J, de Jonge E, Goossens A. Measuring adherence among nurses one year after training in applying the modified early warning score and situation-background-assessment-recommendation instruments . Resuscitation 2011;82:1428–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCulloch P, Rathbone J, Catchpole K. Interventions to improve teamwork and communications among healthcare staff . Br J Surg 2011;98:469–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kazdin AE. Research design in clinical psychology. 4 Suppl ed. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shortell SM, Rousseau DM, Gillies RR, et al. Organizational assessment in intensive care units (ICUs): construct development, reliability, and validity of the ICU nurse-physician questionnaire . Med Care 1991;29:709–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sexton JB, Helmreich RL, Neilands TB, et al. The Safety Attitudes Questionnaire: psychometric properties, benchmarking data, and emerging research . BMC Health Serv Res 2006;6:44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hochwalder J, Bergsten Brucefors A. A psychometric assessment of a Swedish translation of Spreitzer's empowerment scale . Scand J Psychol 2005;46:521–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The organization and management of intensive care units Copyright 1989. http://shortellresearch.berkeley.edu/ICU.htm (accessed 24 Sept 2013).

- 24.Maneesriwongul W, Dixon JK. Instrument translation process: a methods review . J Adv Nurs 2004;48:175–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spreitzer GM. Psychological empowerment in the workplace: dimensions, measurement, and validation . Acad Manage J 1995;38:1442–65 [Google Scholar]

- 26.WHO Conceptual framework for the international classification for patient safety January 2009. http://www.who.int/patientsafety/implementation/taxonomy/publications/en/index.html. (accessed 24 Sept 2013), 2013

- 27.Manojlovich M, DeCicco B. Healthy work environments, nurse-physician communication, and patients’ outcomes . Am J Crit Care 2007;16:536–43 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greenfield LJ. Doctors and nurses: a troubled partnership. Ann Surg 1999;230:279–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singer S, Lin S, Falwell Aet al. Relationship of safety climate and safety performance in hospitals . Health Serv Res 2009;44:399–421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang DT, Clermont G, Kong L, et al. Intensive care unit safety culture and outcomes: a US multicenter study . Int J Qual Health Care 2010;22:151–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosen AK, Singer S, Shibei Z, et al. Hospital safety climate and safety outcomes: is there a relationship in the VA? Med Care Res Rev 2010;67:590–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rabol LI, Andersen ML, Ostergaard D, et al. Descriptions of verbal communication errors between staff. An analysis of 84 root cause analysis-reports from Danish hospitals. BMJ Qual Saf 2011;20:268–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.