Abstract

Objective

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is among the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide, but longitudinal studies of the economic consequences of COPD are scarce. This Danish study evaluated for the first time ever the economic consequences of COPD of an entire nation before and after the diagnosis.

Setting

Records from the Danish National Patient Registry (1998–2010), direct and indirect costs, including frequency of primary and secondary sector contacts and procedures, medication, unemployment benefits and social transfer payments were extracted from national databases.

Participants

131 811 patients with COPD were identified and compared with 131 811 randomly selected controls matched for age, gender, educational level, residence and marital status.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Direct and indirect economic and health consequences of COPD in Denmark in the time period 1998–2010.

Results

Patients with COPD had a poor survival. The average (95% CI) 12-year survival rate was 0.364 (0.364 to 0.368) compared with 0.686 among controls (0.682 to 0.690). COPD was associated with significantly higher rates of health-related contacts, medication use and higher socioeconomic costs. The employment and the income rates of employed patients with COPD were significantly lower compared with controls. The annual net costs, including social transfers were €8572 for patients with COPD. These consequences were present up to 11 years before first-time diagnosis in the secondary healthcare sector and became more pronounced with disease advancement.

Conclusions

This study provides unique national data on direct and indirect costs before and after initial diagnosis with COPD in Denmark as well as mortality, health and economic consequences for the individual and for society. It could be speculated that early identification and intervention might contribute to the solution.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Health Economics

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study truly is unique—providing for the first time ever complete and highly relevant data regarding health and direct and indirect costs of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) of an entire nation over a time period of 12 years.

The 12-year time-window gives a unique possibility to look backwards and forwards from the point of initial diagnosis.

This epidemiological study is solely based on information from national databases leading to some limitations.

The results do not reflect the impact of COPD per se as the pronounced comorbidities of patients with COPD (depression, anxiety, cardiovascular disease, etc) will have an impact, too.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is among the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide, but longitudinal studies of the economic consequences of COPD are scarce.1 2

Smoking, though not necessarily the number of pack years, is slowly declining in the Western world but continues to rise elsewhere and it is estimated that the global impact of COPD will increase in the years to come.3–5

Estimates of COPD prevalence in the industrialised countries range widely, reflecting true differences as well as differences in the definition of COPD and in the diagnostic tools used. Most studies find a 10–15% prevalence of COPD in people from 35 to 40 years and older.6–11 The 17.4% prevalence of COPD in Denmark reported in The Copenhagen City Heart Study is among the highest in the world.12

The burden of COPD on the healthcare sector is substantial and has been described and documented in previous cost-of-illness studies concentrating on treatment of COPD and not considering comorbidity.13–20

Furthermore, the information and assumption of costs have focused on direct costs because indirect costs have generally not been available. Thus, an estimate of total costs of COPD has not yet been achieved.

In Denmark, it is possible to calculate direct and indirect costs of any given disease because information from public and private hospitals and clinics in the primary and secondary care sectors, including medication, social factors, educational level, income and employment data from all patients is registered in central databases and be linked by the unique civil registration number assigned to all Danish citizens facilitating easy and reliable linkage of data. The aim of this study was to evaluate the direct and indirect economic burden of COPD in Denmark before and after initial diagnosis.

Methods

In Denmark, all hospital contacts (emergency rooms, ambulatory visits, admittances, etc) and primary and secondary diagnoses are registered in the National Patient Registry (NPR).21 The NPR includes administrative information, diagnoses and diagnostic and treatment procedures using several international classification systems, including the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD-10 V.2010).

The NPR is a time-based national database that includes data from all inpatient and outpatient contact, so the data that we extracted are representative of all patients in Denmark who have received a first-time primary and secondary diagnosis of COPD irrespective of other diagnoses. As data are available for the entire observation period, we can trace patients retrospectively and prospectively relative to the time of their diagnosis. Furthermore, all contacts in the primary sector (general practice and specialist care) and the use of medications are recorded in the databases of the National Health Security and the Danish Health and Medicines Agency, respectively.

Even though the study is evaluating a relatively long period of time, there is a risk of underestimating the number of patients with COPD, since those with a contact in the primary sector only but not in the secondary sector are recorded as having had contact but not as having received a diagnosis.

We extracted the following first-time primary or secondary diagnoses from the NPR in the time period 1998–2010: “J44 other COPD” compromised by the following subdiagnoses: “J44.0 COPD with acute lower respiratory infection”, “J44.1 COPD with acute exacerbation, unspecified” and “J44.9 COPD, unspecified”.

“J44.8 other specified COPD” was excluded as well as“J43 emphysema” and “J47 bronchiectasis’’. Data on disease severity were not available.

Using data from the Danish Civil Registration System including information about all partners, their marital status, social factors, education level, employment, incomes, pensions, etc,22 we randomly selected controls of the same age, sex and educational level as the patients.

Neither the NPR nor any other national databases contain information about smoking status.

Social compensation was performed by selecting control participants residing in the same area of the country and with the same marital status as the patients. The ratio of control participants to patients was 1 : 1. Data from patients and matched control participants who could not be identified in the Income Statistics database were excluded from the sample. More than 99% of the observations in the two groups were successfully matched. Patients and matched controls were followed from 1998 to 2010. If a patient or control was not present in the registry on 1 January each year due to death, imprisonment or immigration, the corresponding control or patient control was not included in the dataset for that year.

Information about educational level is very robust for everyone between the ages of 14 and 80 with only little information lacking. On the other hand, there is no available information about educational level for people under the age of 14 years and for a very large proportion of those aged 80 years or more—the latter due to lack of registration of education in the Danish Civil Registration System database. This registration, based on information from the different teaching institutions, did not begin until 1970.

One could argue that a huge proportion of the unregistered persons are unskilled, but we cannot assume that the problem is the same in the control group. To avoid bias, we excluded all persons with COPD where proper matching information was missing.

Patients and matched controls were followed through the entire time period or until death. If diagnosis of COPD of any given individual was made in the first year (1998), we were able to follow that individual 11 years forward in time. If diagnosis of COPD of any given individual was made in the last year (2010), we were able to follow that individual 11 years backwards in time. If diagnosis of COPD of any given individual was made between the first and the last year, we were able to follow that individual backwards and forward in time.

Municipal services such as care of the elderly (home care nursing and general home care) and municipal rehabilitation are not included as they are paid by the municipals.

The economic consequences of COPD were estimated by determining the annual costs per patient diagnosed with COPD and comparing these figures with the healthcare costs in a matched control group. Diagnosis of COPD is presented to the NPR using information from public and private hospitals. These diagnoses rely on clinical information and results of diagnostic procedures (eg, spirometry and bronchoscopy). The procedures are registered but the results of the diagnostic procedure are not recorded in the NPR. The health cost was then divided into annual direct and indirect healthcare costs.

Direct costs included the average costs of hospitalisation and outpatient treatment for separate diagnosis-related groups (DRG) and specific outpatient costs. These costs were all calculated from the Danish Ministry of Health data using DRG and average case-mix costs of hospitals or outpatient costs updated on an annual basis. The use and costs of drugs were obtained from the Danish Health and Medicines Agency consisting of the retail price of each drug (including dispensing costs) multiplied by the number of transactions. The frequencies and costs of consultations with general practitioners and other specialists were based on the National Health Security data.

Indirect costs included those related to reduced unemployment benefits and to social transfer payments. Indirect costs were based on income figures from Income Statistics. The costs were measured on an annual basis and adjusted to 2010 prices in Euros (€1: DKK 7.45).

Cost-of-illness studies measure the economic burden resulting from disease and illness across a defined population and include direct and indirect costs. Direct costs are the value of resources used in the treatment, care and rehabilitation of people with the condition under study. Indirect costs represent the value of economic resources lost because of disease-related work disability or premature mortality. As patients leave the national data registers at the time of death, the indirect costs estimate comprises only the production loss related to disease-related work disability. It is important to distinguish costs from monetary transfer payments such as disability and welfare payments. These payments represent a transfer of purchasing power to the recipients from the general taxpayers but do not represent net increases in the use of resources and, therefore, are not included in the total cost estimate.

Statistical analysis

Data were anonymised and neither individual consent nor ethical approval was required.

The results are presented as means because some patients had a very high resource consumption which, despite leading to a skewed distribution, would not be adequately represented if data were presented as median values. Extreme values were manually validated and no errors were identified.

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS V.9.1.3 (SAS Inc, Cary, North Carolina, USA). Statistical significance of the cost estimates was assessed by non-parametric bootstrap analysis.23 24

Survival was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. HR was estimated using the Cox proportional hazard model.

Results

We identified and extracted 131 811 patients with COPD from the national databases (1998–2010) and compared with 131 811 randomly selected matched controls. The age distribution and education level of patients are shown in table 1. There are a little more female than male patients with COPD—probably because of the age distribution. As expected, most of the patients with an initial diagnosis of COPD are middle-aged or older.

Table 1.

Age, gender and education level distribution of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

| Gender | N | Per cent |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 63 342 | 48.1 |

| Female | 68 469 | 51.9 |

| Married or cohabiting | 54.0 | |

| Age distribution | ||

| <14 | – | – |

| 14–20 | 136 | 0.1 |

| 20–29 | 394 | 0.3 |

| 30–39 | 1717 | 1.3 |

| 40–49 | 6664 | 5.1 |

| 50–59 | 19 601 | 14.9 |

| 60–69 | 38 297 | 29.1 |

| 70–79 | 51 524 | 39.1 |

| 80–92 | 13 478 | 10.2 |

| ≥92 | – | – |

| Education level | ||

| Primary | 80 483 | 61.1 |

| Secondary | 864 | 0.7 |

| Vocational | 40 050 | 30.4 |

| Short college | 1824 | 1.4 |

| Medium college | 6784 | 5.1 |

| Master/PhD | 1806 | 1.4 |

| Total | 131 811 | 100.0 |

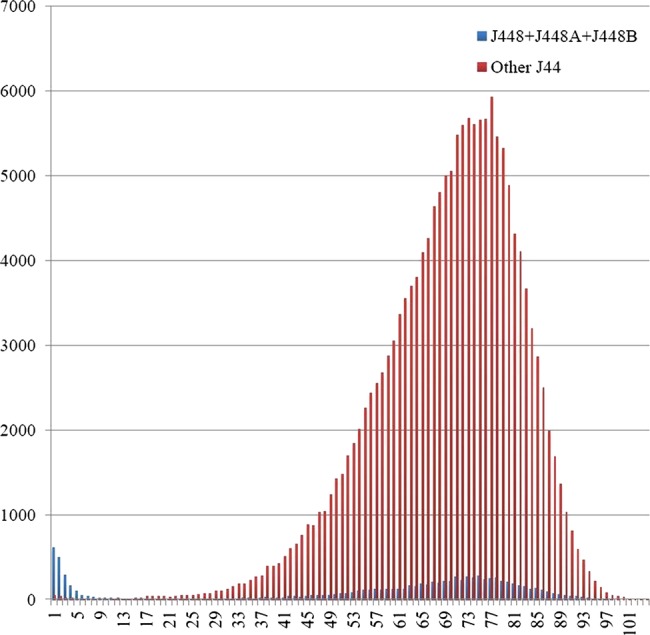

Figure 1 shows distribution of all the included patients with COPD (in red). In blue are the excluded patients with a diagnosis of “J44.8 other specified COPD” which primarily is younger people with a diagnosis of chronic asthmatic bronchitis.

Figure 1.

Distribution of included (red) and excluded cases (blue) on the basis of diagnosis according to age (x axis) and number (y axis).

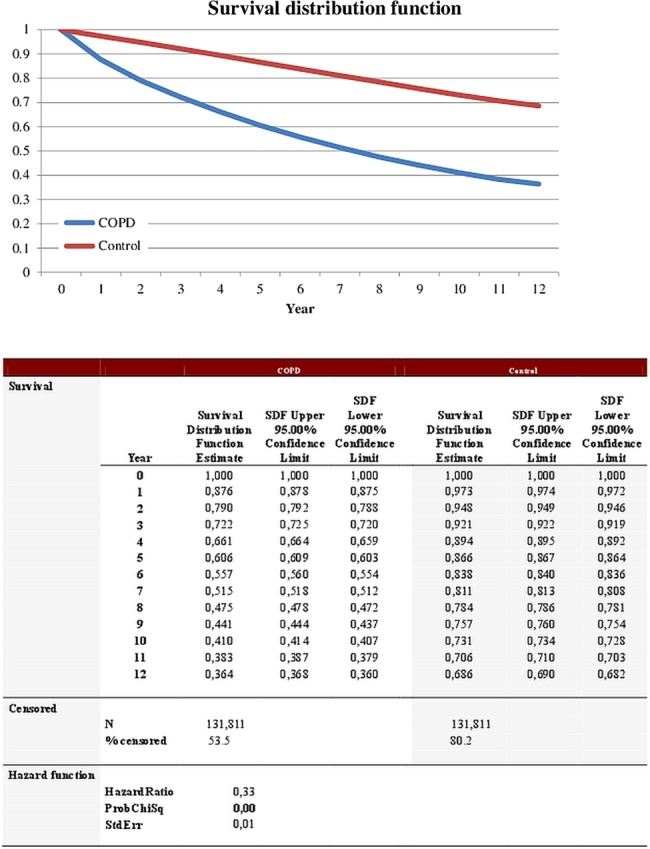

Figure 2 displays survival distribution of patients with COPD and controls showing a decline in survival of patients with COPD compared with controls.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival distribution of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (blue) and controls (red) estimated using the Cox proportional hazard model.

The percentages of patients with COPD and controls receiving various healthcare and income are shown in table 2. COPD is associated with significantly higher rates of health-related contact (outpatient and inpatient treatment as well as primary care), use more medication, have more persons on various public transfer incomes and less people earning income from employment compared with controls.

Table 2.

Percentages of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and controls who receive income and various healthcare services (after diagnosis)

| COPD (%) | Controls (%) | p Value (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outpatient treatment | 64.9 | 36.2 | <0.01 |

| Inpatient treatment | 53.8 | 18.8 | <0.01 |

| Medication | 98.1 | 85.9 | <0.01 |

| Public health insurance | 99.0 | 95.6 | <0.01 |

| Income from employment | 16.7 | 23.8 | <0.01 |

| Public transfer income total | 90.3 | 83.8 | <0.01 |

| Pension | 60.3 | 63.8 | <0.01 |

| Other public transfers | 27.6 | 18.6 | <0.01 |

| Sick pay (publicly funded) | 5.5 | 3.6 | <0.01 |

(Bootstrapped Cochran-Armitage test showing whether the fraction received is significant for each expense type.) The values given are in percentages.

The annual average health costs and income of patients with COPD before and after diagnosis compared with controls are displayed in table 3. COPD is associated with significantly higher rates of health-related costs, medication use and lower income rates compared with controls before and increasingly so after diagnosis.

Table 3.

Health costs and income of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) before and after diagnosis compared with controls

| COPD (€) | Controls (€) | p Value (€) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before diagnosis | |||

| N | 708 329 | 708 343 | |

| Outpatient treatment | 335 | 227 | <0.01 |

| Inpatient treatment | 1534 | 904 | <0.01 |

| Medication | 918 | 434 | <0.01 |

| Public health insurance | 357 | 278 | <0.01 |

| Income from employment | 7947 | 11 418 | <0.01 |

| Public transfer income total | 12 858 | 11 167 | |

| Pension | 7029 | 6824 | <0.01 |

| Other public transfers | 5450 | 4104 | <0.01 |

| Sick pay (public funded) | 378 | 238 | <0.01 |

| Direct health costs | 3144 | 1843 | |

| Indirect costs, foregone earnings | 3471 | ||

| Sum of direct and indirect costs | 6616 | 1843 | |

| Net costs | 4773 | ||

| Social transfer payments | 12 858 | 11 167 | |

| Net costs including transfers | 6464 | ||

| After diagnosis | |||

| N | 597 235 | 776 674 | |

| Outpatient treatment | 789 | 429 | <0.01 |

| Inpatient treatment | 5563 | 1736 | <0.01 |

| Medication | 1782 | 610 | <0.01 |

| Public health insurance | 515 | 361 | <0.01 |

| Income from employment | 4509 | 6800 | <0.01 |

| Public transfer income total | 13 888 | 13 122 | |

| Pension | 9171 | 10 317 | <0.01 |

| Other public transfers | 4361 | 2634 | <0.01 |

| Sick pay (publicly funded) | 356 | 171 | <0.01 |

| Direct health costs | 8650 | 3135 | |

| Indirect costs, foregone earnings | 2291 | ||

| Sum of direct and indirect costs | 10 941 | 3135 | |

| Net costs | 7806 | ||

| Social transfer payments | 13 888 | 13 122 | |

| Net costs including transfers | 8572 | ||

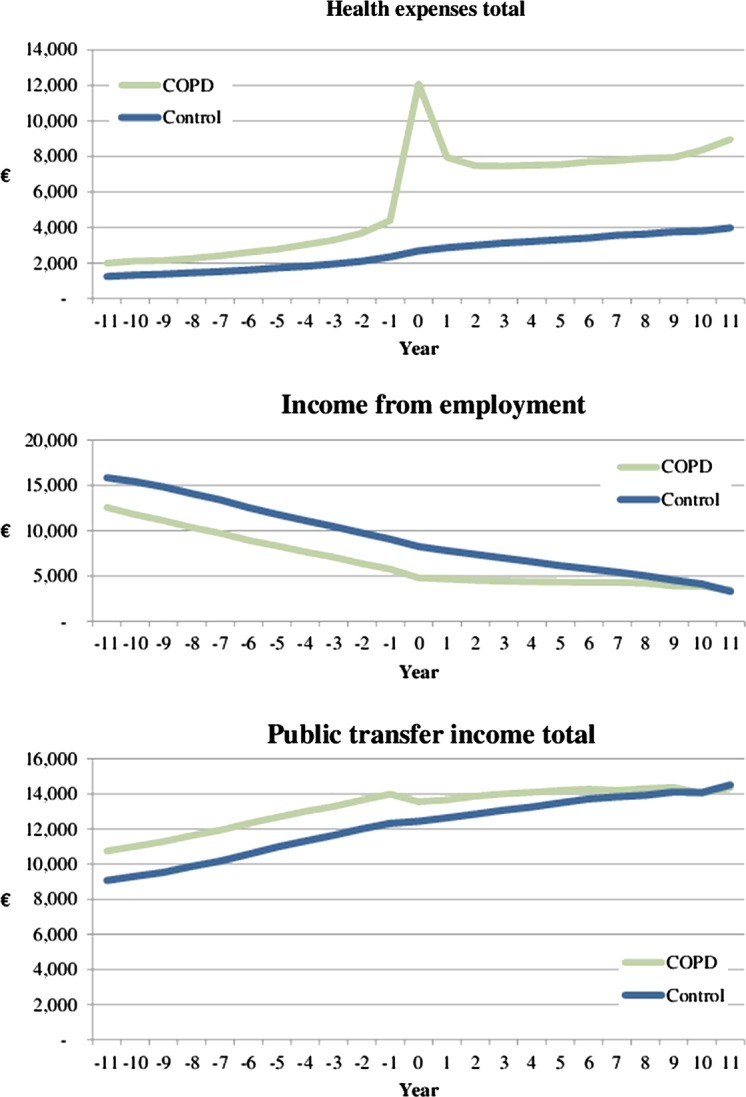

Figure 3 shows total health expenses, income from employment and public transfer income before and after diagnosis of COPD compared with controls.

Figure 3.

Total health expenses, income from employment and public transfer income in Euros before and after diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (green) compared with control participants (blue).

For every year, the total health expenses are significantly higher for patients with COPD. A peak in expenses is seen at the time of diagnosis.

For COPD, the income from employment is significantly lower and the total public transfer income is significantly higher than for controls—even 11 years before the diagnosis has been given.

Both effects diminish over time due to people getting older and retiring from work.

In figure 3, the x axis begins at –11 and stops at 11 years. In year 0 all cases and their controls are present. When moving backwards from 0 to –11, every year will hold less and less cases (and controls) because the ones diagnosed with COPD in 1998 were not followed backwards in time, the ones diagnosed with COPD in 1999 were only followed backwards 1 year in time and so on. The same is true when moving forward from years 0 to 11 because the ones diagnosed with COPD in 2010 were not followed forward in time, the ones diagnosed with COPD in 2009 were only followed forward 1 year in time and so on.

One should be cautious to compare 1 year with another in the figures, because two neighbour years will not be identical but are composed of some identical cases and some cases that differ completely.

As an example, at year –11, the cases diagnosed with COPD in 2010 are shown (thus we are 11 years before the time of the diagnosis). Year –10 hold the cases who got diagnosed in 2010 plus the cases diagnosed in 2009 (thus we are 10 years before the time of the diagnosis).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first epidemiological COPD study that evaluates the direct and indirect costs of COPD at a national level.

The 12-year time-window gives a unique possibility to look backwards and forwards from the point of initial diagnosis. Including every person at a national level with a first-time diagnosis of COPD and randomly selected controls matched for age, gender, educational level, residence and marital status provides a very large amount of persons and data, making the direct and indirect results more complete and robust.

The study has provided several information of interest and confirms the following general beliefs about COPD: patients with an initial primary or secondary diagnosis of COPD had a poor survival. The average (95% CI) 12-year survival rate was 0.364 (0.364 to 0.368) compared with 0.686 among controls (0.682 to 0.690).

COPD was associated with significantly higher rates of health-related contacts, medication use and higher socioeconomic costs. The employment rates and the income rates of employed patients with COPD were significantly lower compared with controls.

The annual net costs after initial diagnosis including social transfers were €8572 for patients with COPD.

These consequences were present up to 11 years before first diagnosis in the secondary sector and became more pronounced with disease advancement.

Determining the economic consequences of COPD is complex. With an accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment, patients’ risk of exacerbation decreases as well as the associated costs and maybe even death (although still controversial). In addition, quality of life improves. On the other hand, the diagnostic procedures, treatment and management of COPD add to the direct costs. However, even when we include the costs associated with the diagnosis and treatment of COPD, our study showed that patients with COPD incur a significant economic burden because the lower employment rates and the lower income rates of employed patients with COPD exceed the direct costs of the disease. These factors influence the costs and should be included in the disease burden.

This epidemiological study is solely based on information from national databases leading to some limitations.

The results do not reflect the impact of COPD per se as the pronounced comorbidities of patients with COPD (depression, anxiety, cardiovascular disease, etc) will have an impact too. By adjusting for the aforementioned available match factor, including educational level, we have tried to minimise this effect. Especially, educational level is a good parameter to use if one wants to level out economical differences. However, social factors that we are not aware of can have an impact on the outcome and explain some of the observed differences.

Ideally, we would have adjusted for smoking status but this information is not registered in any of the national databases in Denmark.

In Denmark, ICD-10 classification is used only in the secondary health sector (hospitals) and not in the primary health sector (general practitioners). Even though this study spans 12 years and includes all with an initial primary or secondary ICD-10 diagnosis of COPD—and the majority of known patients with COPD are believed to be included over time—there is a risk of underestimation. Patients with COPD who are only followed in the primary healthcare sector during the study period are not included and this will bias the results as these patients will tend to be less sick. This fact will tend to overestimate the direct and indirect costs of COPD.

The accuracy of the diagnosis and management is sensitive to the diagnostic criteria used by the reporting doctors. The people aged below 30–40 years with a diagnosis of COPD may—at least to some extent—be due to misclassification.

Furthermore, although J44 by far is the most common diagnosis used in COPD, several different diagnoses deriving from J40 (bronchitis), J41 (simple and mucopurulent chronic bronchitis), J43 (emphysema) and J47 (bronchiectasis) are also used to some (unknown) extent. We have chosen to exclude these diagnoses as well as J44.8 other specified COPD. It could be argued that a large proportion of these excluded individuals are likely to have COPD, but because this is an epidemiological study, entirely based on registry data, we decided to include only those with a specific diagnosis of COPD.

By allowing primary and secondary diagnosis of COPD, some correction of this problem has taken place but may have opened up for adding further comorbidity.

In the control group, there will be a number of undiagnosed patients with COPD (approximately 10%), thus introducing a bias tending to reduce the difference in costs between the two groups in our study.25

Conclusions

This study provides unique data at a national level regarding direct and indirect costs before and after initially diagnosed COPD as well as serious mortality, health and economic consequences for the individual patient and for society.

As the economic consequences are present years prior to the first primary or secondary diagnosis of COPD in the secondary health sector, it could be speculated that early identification and intervention might be part of the solution.

Adequate treatment may reduce the consequences of COPD but, if socially and economically significant reductions in morbidity, mortality and social impact are to be achieved, much earlier disease identification and management are needed. More research and evaluation of case finding strategies and disease management programmes are needed.26

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: AL participated in planning, statistics, writing and discussion. OH participated in planning, writing and discussion. PT participated in writing and discussion. JK participated in planning, statistics and writing. RI participated in statistics and writing. PJ participated in planning, writing and discussion.

Funding: This study was supported by an unrestricted grant from the Respironics Foundation and from a grant from Center for Healthy Aging, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Copenhagen.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are avaliable.

References

- 1. http://www.who.int/en/ (accessed 18 Apr 2013)

- 2.Løkke A, Lange P, Scharling H, et al. Developing COPD a 25 year follow up study of the general population. Thorax 2006;61:935–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Decramer M, Janssens W, Miravittles M. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet 2012;379:1341–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. http://www.goldcopd.org (accessed 18 Apr 2013)

- 5.Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990–2020: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 1997;349:1498–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buist AS, Mcburnie MA, Vollmer WM, et al. International variation in the prevealence of COPD (The BOLD Study): a population-based prevalence study. Lancet 2007;370:741–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindberg A, Jonsson AC, Rönmark E, et al. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease according to BTS, ERS, GOLD and ATS criteria in relation to doctors’ diagnosis, symptoms, age, gender and smoking habits. Respiration 2005;72:471–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Menezes MB, Perez-Padilla R, Jardim JRB, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in five Latin American cities (The Platino Study): a prevalence study. Lancet 2005;366:1875–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim DS, Kim YS, Jung KS, et al. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Korea: a population-based spirometry survey. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;172:842–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Menezes AM, Victora CG, Rigatto M. Prevalence and risk factors for chronic bronchitis in Pelotas, RS, Brazil: a population-based study. Thorax 1994;49:1217–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fukuchi Y, Nishimura M, Ichinose M, et al. COPD in Japan: the Nippon COPD epidemiology study. Respirology 2004;9: 458–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Løkke A, Fabricius PG, Vestbo J, et al. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Copenhagen. Results from the Copenhagen City Heart Study. Ugeskr Laeger 2007;169:3956–60 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Detournay B, Pribil D, Fournier M, et al. The SCOPE Study: health-care consumption related to patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in France. Value Health 2004;7:168–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dahl R, Lofdahl CG. eds The economic impact of COPD in North America and Europe. Analysis of the confronting COPD survey. Respir Med 2003;97(Suppl C):S1–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wouters EFM. Economic analysis of the confronting COPD survey: an overview of the results. Respir Med 2003;97(Suppl C):S3–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grasso ME, Weller WE, Shaffer TJ, et al. Capitation, managed care and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;158:133–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dal Negro RW, Tognella S, Tosatto R, et al. Costs of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in Italy: the SIRIO study (Social Impact of Respiratory Integrated Outcomes). Respir Med 2008;102:92–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Menn P, Heinrich J, Huber RM, et al. for the KORA Study Group Direct medical costs of COPD—an excess cost approach based on two population-based studies. Respir Med 2012;106:540–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blanchette CM, Roberts MH, Petersen H, et al. Economic burden of chronic bronchitis in the United States: a retrospective case-control study. Int J COPD 2011;6:73–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bilde L, Rud SA, Dollerup J, et al. The cost of treating patients with COPD in Denmark—a population study of COPD patients compared with non-COPD controls. Respir Med 2007;101:539–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M. The Danish National Patient Register (in Danish). Scand J Public Health 2011;39:30–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pedersen CB. The Danish Civil Registration System (in Danish). Scand J Public Health 2011;39:22–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agresti A. Categorical data analysis. 2nd edn New York: Wiley, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. An introduction to the bootstrap. London: Chapman & Hall, 1993. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shahab L, Jarvis MJ, Britton J, et al. Prevalence, diagnosis and relation to tobacco dependence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a nationally representative population sample. Thorax 2006;61:1043–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Løkke A, Ulrik CS, Dahl R, et al. Detection of previously undiagnosed cases of COPD in a high-risk population identified in general practice. COPD 2012;9:458–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.