Abstract

Introduction

Recent research shows that advance care planning (ACP) for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is uncommon and poorly carried out. The aim of the present study was to explore whether and to what extent structured ACP by a trained nurse, in collaboration with the chest physician, can improve outcomes in Dutch patients with COPD and their family.

Methods and analysis

A multicentre cluster randomised controlled trial in patients with COPD who are recently discharged after an exacerbation has been designed. Patients will be recruited from three Dutch hospitals and will be assigned to an intervention or control group, depending on the randomisation of their chest physician. Patients will be assessed at baseline and after 6 and 12 months. The intervention group will receive a structured ACP session by a trained nurse. The primary outcomes are quality of communication about end-of-life care, symptoms of anxiety and depression, quality of end-of-life care and quality of dying. Secondary outcomes include concordance between patient's preferences for end-of-life care and received end-of-life care, and psychological distress in bereaved family members of deceased patients. Intervention and control groups will be compared using univariate analyses and clustered regression analysis.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval was received from the Medical Ethical Committee of the Catharina Hospital Eindhoven, the Netherlands (NL42437.060.12). The current project provides recommendations for guidelines on palliative care in COPD and supports implementation of ACP in the regular clinical care.

Clinical trial registration number

NTR3940.

Keywords: Advance Care Planning, End-of-life Care, Palliative Care, COPD

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The present study is a large, adequately powered, multicentre randomised controlled trial to investigate the effects of advance care planning (ACP) in patients with (very) severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

The results from this study will help to implement ACP in the regular clinical care and will provide recommendations for guidelines on palliative care in COPD.

Quality of end-of-life care and dying will be assessed subjectively and retrospectively. Therefore we will use well-validated instruments to overcome this limitation.

The current intervention consists of one single intervention, whereas ACP is an ongoing process of communication. However, with this intervention we aimed to facilitate this continuous process between patients, families and physicians.

Introduction

Advance care planning (ACP) provides patients with an opportunity to plan their future care, should they become incapable of participating in medical treatment decisions. These discussions can result into documentation of end-of-life care preferences in an advance directive.1 However, ACP is not limited to the completion of advance directives. ACP is an ongoing process in which patients, together with healthcare professionals and loved ones, discuss topics such as goals of care, resuscitation and life support, palliative care options and surrogate decision-making.2

Previous studies have shown that ACP increases the occurrence of discussions on it,3 4 improves concordance between patient's preferences and end-of-life care received5–7 and improves quality of care at the end-of-life8 in different adult populations. Despite the fact that chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a leading cause of mortality worldwide9 and unexpected deaths occur frequently,10 ACP studies are rarely focused on patients with COPD. A prospective cross-sectional study showed that outpatients with COPD Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) stage III or IV are able to discuss preferences about life-sustaining treatments and are willing to discuss end-of-life care preferences. However, discussions about end-of-life care are rare and patients rated the quality of patient–physician communication about end-of-life care as poor.11 The most common endorsed barriers for end-of-life care communication reported by physicians are lack of time, anxiety to take away patient's hope and the assumption that the patient is not ready to talk about end-of-life care.12

Although patients often prefer doctors to discuss ACP, they also accept other healthcare professionals as sources of ACP information. Nurses, for example, have specific skills that may facilitate communication about end-of-life care. They can provide prognostic information and support patients’ hopes by understanding individual aspects of hope, focusing on patient's quality of life and building trust with patients.13

However, to date it remains unknown whether and to what extent structured ACP, by a trained nurse in collaboration with the chest physician, can improve outcomes in Dutch patients with COPD and their family. Therefore, we have designed a cluster-randomised controlled trial on the efficacy of structured ACP on quality of end-of-life care communication and quality of end-of-life care in Dutch patients with COPD. The current manuscript describes the research protocol and provides an outline of the possible strengths, weaknesses and clinical consequences.

Hypothesis to be examined in the study

We hypothesise that structured ACP by a trained nurse, in collaboration with the patient's physician, can improve quality of end-of-life care communication, as well as quality of end-of-life care and quality of dying for patients with COPD. In addition, we hypothesise that structured ACP will not result in increased symptoms of anxiety or depression.

Methods and analysis

Study design

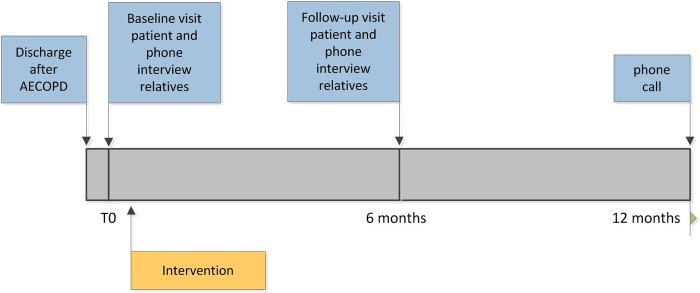

A multicentre, cluster randomised controlled trial has been designed. Patients with COPD who were recently discharged after an exacerbation will be recruited from an academic hospital and from two general hospitals in the Netherlands. Patients in the intervention group will receive an ACP intervention within 4 weeks after discharge. The control group will receive usual care. The intervention and control groups will be assessed at baseline and 6 and 12 months after enrolment (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Timing of the interviews and intervention: all patients receive data collection in the blue boxes; only patients of clinicians randomised to the intervention group receive the intervention.

Eligibility criteria

Eligible patients are those who satisfy all of the following criteria:

A diagnosis of severe-to-very severe COPD (GOLD grade III or IV).14

Discharged after hospital admission for a COPD exacerbation.

At least one loved one, who will participate in the study.

Patients will be excluded if they are unable to complete the questionnaires because of cognitive impairment or if they are unable to speak or understand Dutch.

Intervention

Respiratory nurse specialists will receive a 2-day training to be able to perform the intervention. The training will consist of theory about the importance and benefits of ACP for patients with COPD and their loved ones. End-of-life care communication skills and the structured ACP session during the study will be taught and practiced. The participants will be asked to perform ACP with a standardised patient. Investigators will use a checklist to confirm adherence to the standardised protocol for ACP and provide certification if the participants have achieved competency.

Certified respiratory nurse specialists will provide the structured ACP session in the patient's home environment in the presence of the patient and his or her loved one(s) within 4 weeks after discharge. The session will be prepared with the chest physician in advance. The structured ACP session will pay attention to several elements (box 1). The content will be adapted to the patient's needs. The duration will be about 1.5 h. Respiratory nurse specialists will be supervised by the research project team regularly to guarantee the quality of the structured ACP session.

Box 1. Elements of structured advance care planning (ACP) intervention.

Reflection on patient's goals, values and beliefs.

Understanding the current and future medical situation, possible treatments and outcomes.

Understanding life-sustaining treatments.

Determining wishes regarding the current and future care.

Encouraging discussions on ACP with healthcare providers and loved ones.

Appointment of a surrogate decision-maker.

As part of the structured ACP session, the respiratory nurse specialists will complete, together with the patient, a feedback form showing the patient's: general goals of care; preferences for life-sustaining treatments (cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), non-invasive positive pressure ventilation and mechanical ventilation); and questions and concerns regarding end-of-life care. This feedback form will be provided to the patient, the chest physician and the general practitioner. Finally, the patients will receive a brochure on palliative care for patients with COPD. This brochure is based on the Dutch guideline ‘palliative care for patients with COPD’ and was developed for patients and their loved ones by the Lung Foundation Netherlands.

Outcomes

The following variables will be recorded during home visits at baseline and after 6 months in patients in the intervention and usual care groups: demographics (including age, sex, educational level, religion); smoking history; medical history; current medication; postbronchodilator forced expiratory volume in the 1 s; use of long-term oxygen therapy and use of non-invasive positive pressure ventilation.

Primary outcomes

The primary outcomes for all patients are:

Quality of communication (QOC) about end-of-life care (QOC)15;

Symptoms of anxiety and depression (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)).16

For patients who died during the study period, the primary outcomes are:

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes are:

Concordance between patient's preferences for end-of-life care (patient's preferences for CPR and mechanical ventilation; End-of-life Preferences Interview (ELPI)19 and received end-of-life care (lifesustaining treatment before dying; Toolkit After-Death Bereaved Family Member Interview))17;

Psychological distress in bereaved family members of deceased patients with COPD (HADS16; Inventory of Complicated Grief (ICG)20).

Patients in the intervention and usual care group will receive a phone call 12 months after enrolment to assess the survival state. If the patient cannot be reached, the participating family members will be contacted. If the patient has deceased during the study period, a bereavement interview will be conducted with the participating family members. The following outcomes will be assessed: QODD18; Toolkit After-Death Bereaved Family Member Interview17; ICG20 and HADS.16

Questionnaires that were not available in Dutch (QOC, ELPI, and Toolkit After-Death Bereaved Family Member Interview) have been translated into Dutch using a forward–backward translation procedure.

Sample size

A sample size calculation with a level of significance of 5% and a power of 90% has shown that 53 patients per group are needed in order to detect a difference of 1 point change in QOC end-of-life care domain score (SD estimated as 2.53 points)15 between the intervention and control groups. A sample size calculation with a level of significance of 5% and power of 90% has shown that 32 deceased patients per group are needed in order to detect a difference of 10 points change in QODD scores between the intervention and control groups. Since we expect a mortality rate within 1 year of about 23% and a dropout rate of about 10% because of other reasons, we will include 150 patients per group.

Recruitment and randomisation

Patients will be informed about the study during their hospital admission for a COPD exacerbation. After discharge, the potential participant will receive a phone call. If the patient wants to participate, an appointment for a first home visit will be made. Informed consent will be obtained at the start of this visit. Each participant will be assigned a study identification number. A list with identification codes linking the participant's names to participant's identification numbers will be stored in a limited access space.

Chest physicians of participating hospitals will be randomised into an intervention or usual care group using sealed opaque envelopes. We will cluster for chest physician to prevent cross contamination between the intervention and usual care groups. Participating patients and their family members will receive the intervention or usual care, depending on the randomisation of their chest physician. The researcher who will visit and phone the participants will not offer ACP.

Data management and statistical analysis

The data will be screened for outliers and missing values. These values will be excluded by list wise deletion. Missing data will be minimised because patients will be visited at home for completing the questionnaires and the researcher will check if all the questions have been answered. The study variables will be tested for normality. Demographic variables (such as age, sex, educational level, religion and smoking history) will be compared between patients in the intervention group and control group, using independent-samples t tests or Mann-Whitney U tests, as appropriate, for continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables.

The differences in the primary outcome measures between the intervention and the usual care groups will be compared using independent-sample t tests or Mann-Whitney U tests, as appropriate. The Wilcoxon signed rank test will be used to compare changes in the primary outcome measures within the intervention and usual care groups. Multivariate regression models will be developed to compare changes in the primary and secondary outcome measures between the intervention and control groups while clustering by physician and controlling for possible confounders. Finally, concordance between the patient's preferences for end-of-life care and the end-of-life care received will be calculated using Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICC) for continuous variables and Cohen's κ for categorical variables.

All statistical analyses will be performed using statistics software (SPSS V.21.0 for Windows, Chicago, Illinois, USA) and STATA V.11.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas, USA) for clustered regression analysis. A priori, a two-tailed p value of <0.05 was considered as significant.

Dissemination

The study will be monitored according to the guidelines of the Dutch Federation of University Medical Centres (NFU) and will be conducted in accordance with the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO). The results will be submitted for publication in peer-reviewed journals and will be presented at (inter)national conferences. Participants will be informed about the results of the study. The results of this project provide direction for further development of palliative care for patients with COPD.

Discussion

The present study has been designed to examine whether and to what extent structured ACP by a trained nurse, in collaboration with the chest physician, can improve outcomes for patients with advanced COPD and their family. The study has several strengths and limitations which will be described below.

Strengths

The current project is designed to improve ACP by overcoming the previously reported physician-endorsed barriers towards ACP. The most common barrier to communication about end-of-life care, endorsed by physicians, is the lack of time.12 The present study will overcome this barrier, because the intervention will be delivered by trained respiratory nurses. Nurses have specific communication skills important for end-of-life care communication, such as listening to patients, being responsive to emotional needs, treating the whole person and respecting patients’ cultural and religious beliefs.21 Another barrier frequently endorsed by physicians is their assumption that patients are not ready to talk about end-of-life care.12 However, research has shown that patients with severe-to-very severe COPD have clear preferences concerning life-sustaining treatments and are willing to discuss end-of-life care.11 22 These discussions about end-of-life care are particularly important for patients with COPD, because they follow a disease trajectory characterised by a gradual decline in health status and punctuated by exacerbations.23 Although survival in patients with COPD is hard to predict,24 research has shown that exacerbations are associated with an increased risk of dying.25 Patients who survived a hospitalisation for an exacerbation often experience an increase in the intensity of dyspnoea and had a poor quality of life.26 27 Therefore, clinicians see exacerbations as a clinical event that defines an important transition in the course of the disease and is therefore a moment to initiate ACP.28 In addition, patients who were hospitalised for an exacerbation describe the hospital admission itself as chaotic, but are willing to discuss their preferences for end-of-life care after discharge.29 Consequently, an approach may be to discuss ACP after discharge.

The present study also has some methodological strengths. First, the present study is a randomised controlled trial. This study design in general has good validity and causal conclusions can be drawn.30 Second, patients will be recruited from one academic and two general hospitals in the Netherlands to guarantee internal and external validity. Finally, we will perform cluster analysis to prevent cross contamination between the intervention and usual care groups and allocation is concealed using sealed opaque envelops in order to prevent systematic biases.

Limitations

The present study has the following limitations: First, it may be possible that eligible patients and family members who refuse participation in this study are less willing to discuss issues concerning end-of-life care than participating patients and family members. Demographics will be collected from eligible patients and family members who refuse participation in the study for comparison with participating patients and family members. However, since these patients may also refuse an ACP intervention in the clinical practice, this may mitigate the importance of this limitation. Second, dropout is to be expected and is unavoidable in a longitudinal study including patients with severe disease. We expect about 23% of the patients to die during the study period.31 In addition, we expect about 10% to withdraw because of other reasons.22 Third, in the present study, the perception of the patient of communication about end-of-life care will be assessed. The present project does not provide objective measures for QOC. In addition, the present project assesses the family members’ perception of quality of end-of-life care and quality of dying and does not provide objective measures for quality of end-of-life care and quality of dying. However, we believe that the perception from the patient and his or her family members is the most important construct with respect to end-of-life care. Moreover, validated instruments will be used to assess the patient perception from QOC about end-of-life care15 and the family members’ perception of quality of end-of-life care and QODD.17 18 Fourth, quality of end-of-life care and quality of dying will be assessed retrospectively. We do not assess prospectively quality of end-of-life care in terminally ill patients. Prospectively identifying terminally ill patients with COPD is extremely difficult.10 Moreover, we want to avoid the extra burden for dying patients. However, retrospective assessments may be altered by grief or recall difficulties.32 This should be taken into account in interpreting the results. Fifth, it may be possible that QOC about end-of-life care at baseline is different between the physicians in the intervention group and physicians in the usual care group. Therefore, data analysis will correct for baseline QOC scores. Sixth, it may be possible that participants in the usual care group will be stimulated to discuss their life-sustaining treatment preferences or end-of-life care due to the assessment of their preferences during the study period. However, a prior study suggested that these questionnaires do not have a significant effect on discussions about end-of-life care.33 Finally, the current intervention consists of a single session with a trained respiratory nurse specialist and providing a feedback form. We acknowledge that ACP should not be a single intervention, but should be an ongoing process between patients, their loved ones and professional caregivers during the course of the disease. However, the aim of the intervention in the present study is to facilitate the ongoing process of ACP between patients, families and physicians.

Clinical consequences

The present study will examine the effects of structured ACP by a trained respiratory nurse. When this relatively simple intervention is able to improve outcomes for patients regarding end-of-life care and their loved ones, the project can be followed by implementation of ACP in the regular clinical care. In addition, the current project provides recommendations for guidelines on palliative care in COPD. Moreover, if the current intervention is able to improve outcomes for patients with COPD and their families, this programme can possibly be implemented for other patients with advanced chronic life-limiting diseases, like congestive heart failure or idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Indeed, mortality rates are also high in these patient populations.34 35

Conclusion

To date, ACP for patients with severe-to-very severe COPD is uncommon and poorly carried out. The present study aims to improve quality of end-of-life care communication, as well as quality of end-of-life care and quality of dying for patients with COPD using structured ACP by a trained nurse, in collaboration with the patient's chest physician. This study is necessary to develop an evidence-based ACP programme in the Netherlands. Here, the study protocol is described and a preliminary analysis of the possible strengths and weaknesses is outlined.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: EFMW is the principal investigator and together with DJAJ and MAS designed and established the study. CHMH is responsible for the recruitment, data collection and data analysis. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This project was supported by Grant 3.4.12.022 of Lung Foundation Netherlands, Leusden, the Netherlands.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval has been obtained from the Medical Ethical Committee of the Catharina Hospital Eindhoven, the Netherlands (NL42437.060.12) and is registered in the Dutch Trial Register (NTR3940).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Barnes KA, Barlow CA, Harrington J, et al. Advance care planning discussions in advanced cancer: analysis of dialogues between patients and care planning mediators. Palliat Support Care 2011;9:73–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel K, Janssen DJ, Curtis JR. Advance care planning in COPD. Respirology 2012;17:72–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clayton JM, Butow PN, Tattersall MH, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a prompt list to help advanced cancer patients and their caregivers to ask questions about prognosis and end-of-life care. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:715–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dexter PR, Wolinsky FD, Gramelspacher GP, et al. Effectiveness of computer-generated reminders for increasing discussions about advance directives and completion of advance directive forms. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1998;128:102–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, et al. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010;340:c1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirchhoff KT, Hammes BJ, Kehl KA, et al. Effect of a disease-specific advance care planning intervention on end-of-life care. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60:946–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morrison RS, Chichin E, Carter J, et al. The effect of a social work intervention to enhance advance care planning documentation in the nursing home. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:290–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bischoff KE, Sudore R, Miao Y, et al. Advance care planning and the quality of end-of-life care in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013;61:209–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lopez AD, Shibuya K, Rao C, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: current burden and future projections. Eur Respir J 2006;27:397–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Claessens MT, Lynn J, Zhong Z, et al. Dying with lung cancer or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: insights from SUPPORT. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000;48(Suppl 5):S146–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janssen DJ, Spruit MA, Schols JM, et al. A call for high-quality advance care planning in outpatients with severe COPD or chronic heart failure. Chest 2011;139:1081–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knauft E, Nielsen EL, Engelberg RA, et al. Barriers and facilitators to end-of-life care communication for patients with COPD. Chest 2005;127:2188–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reinke LF, Shannon SE, Engelberg RA, et al. Supporting hope and prognostic information: nurses’ perspectives on their role when patients have life-limiting prognoses. J Pain Symptom Manage 2010;39:982–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vestbo J, Hurd SS, Rodriguez-Roisin R. The 2011 revision of the global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD (GOLD)—why and what? Clin Respir J 2012;6:208–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Engelberg R, Downey L, Curtis JR. Psychometric characteristics of a quality of communication questionnaire assessing communication about end-of-life care. J Palliat Med 2006;9:1086–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teno JM, Clarridge B, Casey V, et al. Validation of Toolkit After-Death Bereaved Family Member Interview. J Pain Symptom Manage 2001;22:752–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Downey L, Curtis JR, Lafferty WE, et al. The Quality of Dying and Death Questionnaire (QODD): empirical domains and theoretical perspectives. J Pain Symptom Manage 2010;39:9–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borreani C, Brunelli C, Miccinesi G, et al. Eliciting individual preferences about death: development of the End-of-Life Preferences Interview. J Pain Symptom Manage 2008;36:335–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK, Reynolds CF, III, et al. Inventory of complicated grief: a scale to measure maladaptive symptoms of loss. Psychiatry Res 1995;59:65–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reinke LF, Shannon SE, Engelberg R, et al. Nurses’ identification of important yet under-utilized end-of-life care skills for patients with life-limiting or terminal illnesses. J Palliat Med 2010;13:753–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janssen DJ, Spruit MA, Schols JM, et al. Predicting changes in preferences for life-sustaining treatment among patients with advanced chronic organ failure. Chest 2012;141:1251–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lorenz KA, Shugarman LR, Lynn J. Health care policy issues in end-of-life care. J Palliat Med 2006;9:731–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fox E, Landrum-McNiff K, Zhong Z, et al. Evaluation of prognostic criteria for determining hospice eligibility in patients with advanced lung, heart, or liver disease. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments. JAMA 1999;282:1638–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, et al. Illness trajectories and palliative care. BMJ 2005;330:1007–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rocker GM, Dodek PM, Heyland DK. Toward optimal end-of-life care for patients with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: insights from a multicentre study. Can Respir J 2008;15:249–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lynn J, Ely EW, Zhong Z, et al. Living and dying with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000;48(Suppl 5):S91–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reinke LF, Engelberg RA, Shannon SE, et al. Transitions regarding palliative and end-of-life care in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or advanced cancer: themes identified by patients, families, and clinicians. J Palliat Med 2008;11:601–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seamark D, Blake S, Seamark C, et al. Is hospitalisation for COPD an opportunity for advance care planning? A qualitative study. Prim Care Respir J 2012;21:261–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richter B, Berger M. Randomized controlled trials remain fundamental to clinical decision making in type II diabetes mellitus: a comment to the debate on randomized controlled trials (for debate) [corrected]. Diabetologia 2000;43:254–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Groenewegen KH, Schols AM, Wouters EF. Mortality and mortality-related factors after hospitalization for acute exacerbation of COPD. Chest 2003;124:459–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Higginson I, Priest P, McCarthy M. Are bereaved family members a valid proxy for a patient's assessment of dying? Soc Sci Med 1994;38:553–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Au DH, Udris EM, Engelberg RA, et al. A randomized trial to improve communication about end-of-life care among patients with COPD. Chest 2012;141:726–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McMurray JJ, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, et al. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail 2012;14:803–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barlo NP, van Moorsel CH, van den Bosch JM, et al. Predicting prognosis in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2010;27:85–95 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.