Abstract

Objectives

Apolipoprotein C3 (ApoC3) polymorphisms have been suggested to be associated with risk of coronary heart disease (CHD). However, the results of relevant studies were inconsistent. We aimed to systematically evaluate this issue.

Design

PubMed, EMBASE and Cochrane library databases (up to March 2013) were systematically searched to identify studies evaluating the association between ApoC3 polymorphisms and CHD risk. Two reviewers independently identified studies, extracted and analysed the data. Either a fixed-effects or a random-effects model was adopted to estimate overall ORs.

Studies reviewed

Finally, 20 studies comprising 15 591 participants were included in this systematic review. Fifteen studies with 11 539 individuals were included in the meta-analysis of Sst I polymorphism, four studies comprising 3378 individuals assessed T-455C polymorphism, four studies with 3070 participants evaluated C-482T polymorphism and C1100T polymorphism was assessed by three studies comprising 4662 participants.

Results

Under dominant model, Sst I polymorphism was borderline significantly associated with CHD risk (S1S2+S2S2 vs S1S1, pooled OR=1.19, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.42). Subgroup analyses suggested that Sst I polymorphism was significantly associated with myocardial infarction (MI) risk (pooled OR=1.42, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.91), and Sst I polymorphism was statistically associated with CHD risk among Asian population (pooled OR=1.35, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.69) and in retrospective studies (pooled OR=1.30, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.61). A significant association was observed between T-455C polymorphism and CHD risk (TC+CC vs TT, pooled OR=1.22, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.42). A borderline significant association was suggested between T-455C polymorphism and MI risk (pooled OR=1.21, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.46). C-482T and C1100T polymorphisms were not indicated to be associated with CHD risk or MI risk.

Conclusions

ApoC3 Sst I and T-455C polymorphisms might be associated with CHD risk.

Keywords: Genetics

Strengths and limitations of the study.

The present study comprehensively evaluated the association between apolipoprotein C3 polymorphisms, including Sst I, T-455C, C-482T, C1100T and coronary heart disease risk. The methods of this study were rigorous and were based on the guidelines for conducting and reporting systematic reviews.

Most of the included studies were from Asia, Europe and the USA, so the conclusions may not be true for other ethnic groups. Besides, between-study heterogeneity could not be completely explained.

Introduction

The progression of coronary heart disease (CHD) is complicated and is influenced by multigenetic and environmental factors, and atherosclerosis of the coronary artery is the basic pathogenic factor of CHD.1 Plasma lipids and lipoproteins are important risk factors for atherosclerosis, and genes involved in lipoprotein metabolism might be candidate genes for CHD susceptibility.2 3 Apolipoprotein C3 (ApoC3) is an essential component of circulating particles in the TG-rich lipoprotein, and inhibits the hydrolysis of TG-rich particles by the lipoprotein lipase and their hepatic uptake mediated by apolipoprotein E.4 Therefore, high levels of ApoC3 may cause hypertriglyceridaemia.5 Previous studies supported that ApoC3 might play an important role in CHD development, and the ApoC3 concentration was also associated with CHD risk.6 7

Serum ApoC3 concentration was shown to be influenced by genetic and acquired factors.8 Several polymorphisms have been found in ApoC3 gene, including C-482T, T-455C, Sst I and C1100T polymorphisms.9–12 In recent years, studies have investigated the correlation between these polymorphisms and CHD risk, while the results were inconsistent. The aim of our meta-analysis was to assess the association between ApoC3 polymorphisms and risk of CHD.

Methods

Literature search

Systematic literature searches were conducted before March 2013 in PubMed, EMBASE and Cochrane library databases without restrictions. Combination of the following terms were applied: ‘coronary heart disease’ OR ‘coronary artery disease’’ OR ‘myocardial infarction’ OR ‘acute coronary syndrome’ OR ‘ischemic heart disease’ OR ‘cardiovascular disease’ OR ‘major adverse cardiac event’ OR ‘CHD’ OR ‘CAD’ OR ‘MI’ OR ‘ACS’ OR ‘IHD’ OR ‘MACE’; ‘apolipoprotein C3’ OR ‘apolipoprotein C’ OR ‘apolipoprotein C- III’ OR ‘apolipoprotein C III’ OR ‘APO C3’ OR ‘APOC3” OR ‘APOC’ OR ‘APO C III’ OR ‘APO C- III’; ‘polymorphism’ OR ‘variant’ OR ‘SNP’ OR ‘mutation’. References of relevant articles were also scanned for studies potentially missed in the primary searches. Articles published in English were retrieved. And the retrieved studies were carefully examined to exclude potential duplicates or overlapping data. This meta-analysis was designed, conducted and reported according to PRISMA statement.13

Selection criteria, data extraction and study quality assessment

Studies retrieved from the initial search were then screened for eligible articles. Titles and abstracts were scanned and then full articles were reviewed. We included articles if they met all the following criteria: (1) evaluating the association between ApoC3 polymorphism and CAD and (or) myocardial infarction (MI); (2) OR estimates and their 95% CI were available or could be calculated; (3) each polymorphism included in the meta-analysis should be reported by at least two studies.

Data were extracted independently by two reviewers (BL and YH). The following information was extracted from each study: first author, publication year, country, study design, sample size, gender distribution, mean age, phenotype (disease), genotype of cases and controls, whether the polymorphism(s) evaluated was in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium or not and the genotyping assay method. Any discrepancy was resolved by a third investigator. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) method was applied to assess the study quality.14 The NOS contains eight items and the score ranged from 0 to 9.

Statistical analysis

Dominant model was applied in this study as this genetic model was most widely used in the included studies. Because some studies did not apply dominant model, we recalculated OR values under dominant model. Either a fixed-effects model or a random-effects model was applied to pool the OR estimates of each study, according to heterogeneity across studies. The extent of heterogeneity was checked using the χ2 test and I2 test; p≤0.10 and/or I2>50% indicates a significant heterogeneity. When p>0.10, the fixed-effects model was applied and otherwise we used the random-effects model. Subgroup analysis was applied to explore heterogeneity. Study-specific ORs of CHD were first pooled and then evaluated the association between ApoC3 polymorphisms and MI risk separately. Funnel plots were constructed and Begg's and Egger's tests were used to assess the publication bias, and p≤0.10 was considered to be significant. All analyses were conducted using the Stata software (V.11.0; StatCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

Study selection and characteristics

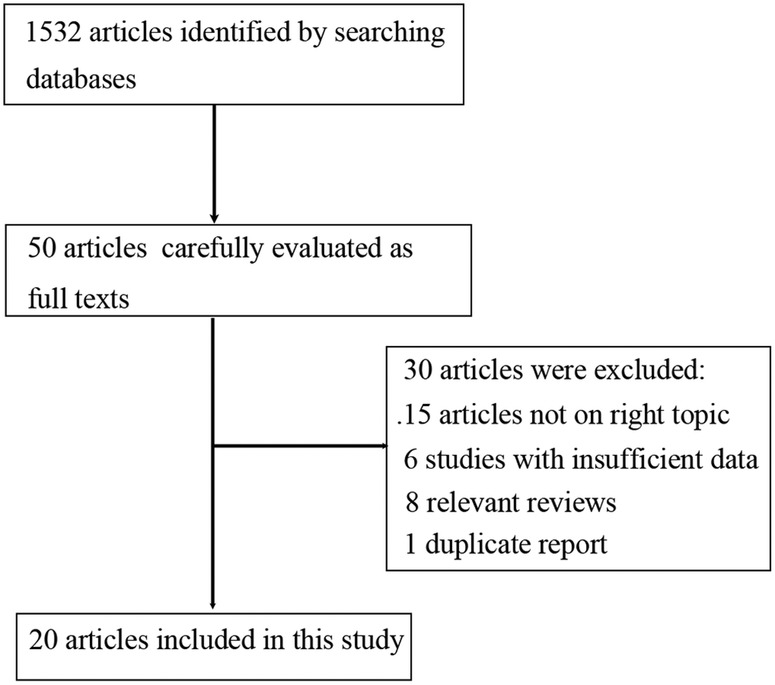

A total of 1532 articles were identified by searching PubMed, EMBASE and Cochrane library databases. Among them, 1482 articles were excluded by screening the titles and abstracts. The remaining 50 articles were carefully evaluated as full texts and 30 articles were excluded. The reasons for exclusion were articles not on right topic (15 articles), insufficient data (six papers), relevant reviews (eight papers) and duplicate reports from the same study (one article). This meta-analysis finally included 20 articles.9–12 15–30 The selection process was shown in figure 1 while the characteristics of those studies were listed in online supplementary table S1. Among these studies, fifteen studies assessed ApoC3 Sst I polymorphism, four studies evaluated ApoC3 T-455C polymorphism, four studies reported ApoC3 C-482T polymorphism and three investigated ApoC3 C1100T polymorphism (several studies reported more than one polymorphism). The results of quality assessment were shown in the online supplementary table S2 and the score of the included studies ranged from 5 to 9.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study selection process.

AOPC3 polymorphisms and risk of CHD

Meta-analysis of Sst I polymorphism

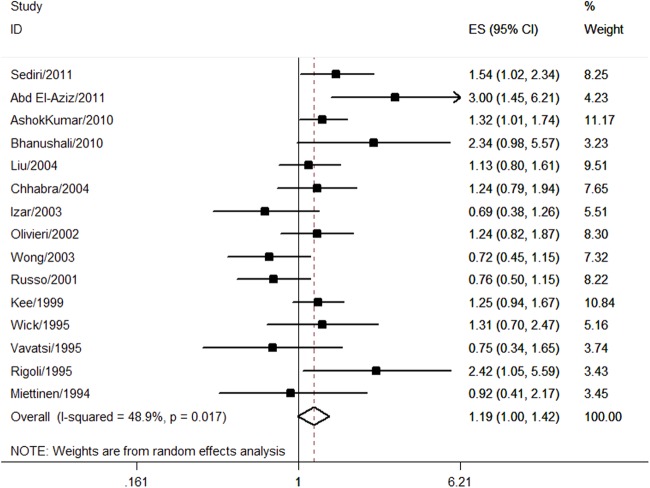

A total of 15 studies with 11 539 individuals were assessed for the association between Sst I polymorphism and CHD risk. Fourteen studies were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium while one study did not report whether Sst I polymorphism was in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium or not.22 Most of the studies used restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) method for DNA genotyping (n=14) and one study applied the immobilised oligonucleotide probes array (IOPA) method.24 Multivariable OR could be extracted from four studies10 20 22 24 (see online supplementary table S3). Under dominant model (S1S2+S2S2 vs S1S1), the pooled univariate OR of all studies was 1.19 (95% CI 1.00 to 1.42; figure 2 and table 1), indicating a borderline significant association between Sst I polymorphism and CHD risk. There was significant heterogeneity among studies (I2=48.9%, p=0.017; figure 2 and table 1). The pooled multivariable OR was 1.11 (0.73 to 1.70), which did not suggest a significant association.

Figure 2.

Association between Sst I polymorphism and coronary heart disease risk.

Table 1.

Meta-analysis results of Sst I, T-455C, C-482T and C1100T polymorphisms

| Polymorphism | Number of studies | Number of participants | Comparison | OR (95% CI) | Heterogeneity |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I2 (%) | p Value | |||||

| Sst I | 15 | 11 539 | S1S2+S2S2 vs S1S1 | 1.19 (1.00 to 1.42) | 48.9 | 0.017 |

| T-455C | 4 | 3378 | TC+CC vs TT | 1.22 (1.06 to 1.42) | 0 | 0.580 |

| C-482T | 4 | 3070 | CT+TT vs CC | 1.06 (0.92 to 1.22) | 0 | 0.788 |

| C1100T | 3 | 4662 | CT+TT vs CC | 1.06 (0.89 to 1.27) | 46.7 | 0.153 |

According to study characteristics, subgroup analysis was adopted, as shown in table 2. Pooled results showed that S1S2 and S2S2 genotyes might increase the risk of CHD in Asian population (pooled OR=1.35, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.69) but not in Caucasian population (pooled OR=1.14, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.41). Study design could also influence the result; Sst I polymorphism was significantly associated with CHD risk in retrospective studies (pooled OR=1.30, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.61) but not in prospective studies (pooled OR=0.98, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.28). Besides, Sst I polymorphism was observed to be significantly associated with MI risk (pooled OR=1.42, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.91) but not CHD risk (pooled OR=1.09, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.35). After excluding the study that did not report Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, the pooled OR was 1.24 (95% CI 1.04 to 1.47). The pooled OR of the studies that applied RFLP method was 1.19 (95% CI 0.98 to 1.44).

Table 2.

Subgroup analysis of Sst I polymorphism

| Groups | OR (95% CI) | Heterogeneity |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| I2 (%) | p Value | ||

| Ethnicity | |||

| Caucasian | 1.14 (0.92 to 1.41) | 54.2 | 0.013 |

| Asian | 1.35 (1.08 to 1.69) | 0 | 0.427 |

| Study design | |||

| Retrospective | 1.30 (1.04 to 1.61) | 39.0 | 0.098 |

| Prospective | 0.98 (0.75 to 1.28) | 52.3 | 0.098 |

| Phenotype | |||

| CHD | 1.09 (0.87 to 1.35) | 46.0 | 0.047 |

| MI | 1.42 (1.06 to 1.91) | 52.3 | 0.099 |

CHD, coronary heart disease; MI, myocardial infarction.

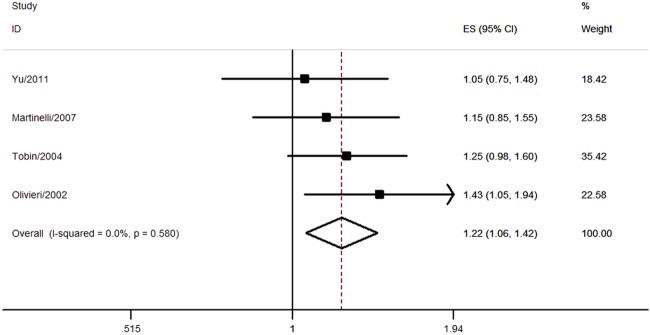

Meta-analysis of T-455C polymorphism

The association between T-455C polymorphism and CHD risk was evaluated by four studies comprising 3378 individuals. All the studies were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. The IOPA method was used by three studies while real-time fluorescence quantitative PCR was applied by one study.9 Only one study reported a multivariable OR of 1.82 (95% CI 1.05 to 3.18), while the unadjusted OR was 1.15 (98% CI 0.85 to 1.5517; see online supplementary table S3). The results indicated a significant association between T-455C polymorphism and CHD risk (TC+CC vs TT, pooled OR=1.22, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.42; figure 3 and table 1). No significant heterogeneity among studies was indicated (I2=0%, p=0.580; figure 3 and table 1). Two studies reported the association between T-455C polymorphism and MI risk, and the pooled result suggested a borderline significant association (pooled OR=1.21, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.46).

Figure 3.

Association between T-455C polymorphism and coronary heart disease risk.

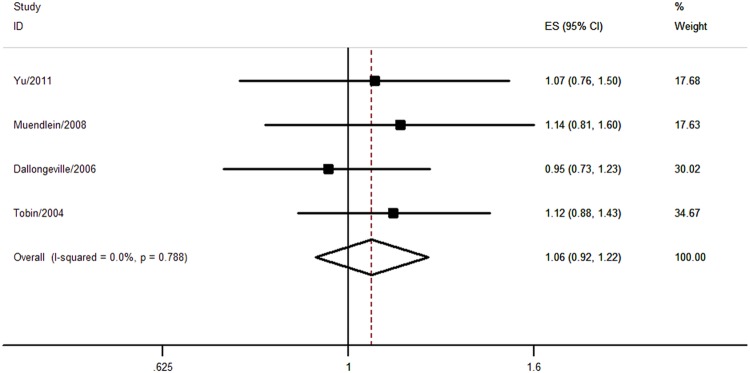

Meta-analysis of C-482T polymorphism

Four studies with 3070 individuals reported the association between C-482T polymorphism and CHD risk. Only one study did not report whether C-482T polymorphism was in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium or not.22 Two studies applied real-time fluorescence quantitative PCR method,9 16 one study used RFLP method22 and the other study adopted the IOPA method.19 Multivariable OR could be extracted from two studies16 18 (see online supplementary table S3). There was no significant association between C-482T polymorphism and CHD risk (CT+TT vs CC, pooled OR=1.06, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.22; figure 4 and table 1). No significant heterogeneity was observed (I2=0%, p=0.788; figure 4 and table 1). Only one study reported the association between C-482T polymorphism and MI risk (OR=1.12, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.43).19

Figure 4.

Association between C-482T polymorphism and coronary heart disease risk.

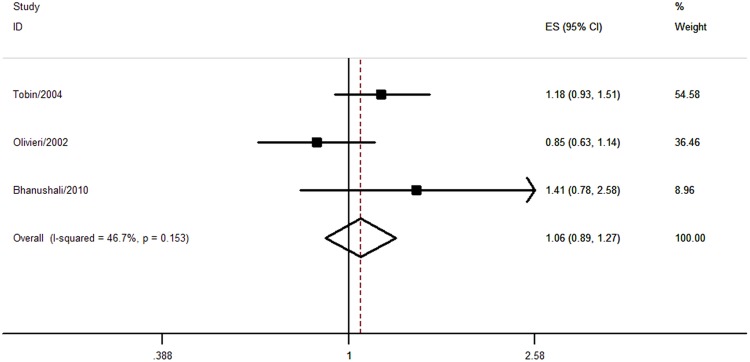

Meta-analysis of C1100T polymorphism

Three studies comprising 4662 participants evaluated the association between C1100T polymorphism and CHD risk. Two studies adopted the IOPA method19 24 and one study used the RFLP method.22 No significant association was found (CT+TT vs CC, pooled OR=1.06, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.27) and no significant heterogeneity was observed (I2=46.7%, p=0.153; figure 5 and table 1). One study evaluated the association between C1100T polymorphism and MI risk (OR=1.18, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.51).19

Figure 5.

Association between C1100T polymorphism and coronary heart disease risk.

Publication bias

Begg's and Egger's tests suggested that no publication bias was found in our meta-analyses.

Discussion

ApoC3 is a glycoprotein synthesised mainly in the liver and the intestinal, and plays an essential role in regulating the serum triglyceride levels. Besides, it can strongly regulate the levels of very-low-density lipoprotein and small dense low-density lipoprotein (LDL) which potentially improves atherosclerosis.31 The clinical research has found that ApoC3 levels were a predictor of risk for the development of CHD.32–34 In the present study, 20 studies were included and four polymorphisms of ApoC3 were evaluated, including C-482T, T-455C, Sst I and C1100T polymorphisms. T-455C polymorphism was suggested to be significantly associated with CHD risk, and ‘C’ allele increased CHD risk by 22% (CT+TT vs CC, pooled OR=1.22, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.42). A borderline significant association was observed between Sst Ipolymorphism and CHD risk, while no evidence suggested a significant association between C-482T and C1100T polymorphisms and CHD risk. Subgroup analysis was applied for Sst I polymorphism, and we found that Sst I polymorphism was significantly associated with MI risk. Besides, Sst I polymorphism was significantly associated with CHD risk in Asian population but not in Caucasian population, indicating that the effect of Sst I polymorphism might be influenced by ethnicity. For retrospective studies, Sst I was indicated to be significantly associated with CHD risk but this association was not confirmed in prospective studies. So, the association between Sst I polymorphism and CHD risk should be interpreted cautiously.

The mechanism of Sst I polymorphism in CHD susceptibility may be multiple. Sst I polymorphism is located in 3′-untranslated region of the ApoC3 gene, and it is possible that this polymorphism is in linkage disequilibrium with other functional polymorphism in the nearby region, such as T-455C polymorphism.10 Sst I polymorphism might alter plasma lipid concentrations. Several studies showed that S2 carriers have higher plasma total cholesterol, TG and LDL-C levels,12 35 36 though other studies did not demonstrate significant difference.10 20 37 Besides, it has been shown that S2 allele might significantly influence dyslipidaemic state and atherosclerosis severity when patients changed their diet from saturated fatty acids to olive oil.38 So, Sst I polymorphism plays an important role in modulating lipid levels response to dietary changes.

T-455C and C-482T polymorphisms were located in the 5′ promoter region and were in a strong linkage disequilibrium with each other. These two polymorphisms have been studied extensively because they could alter the nuclear transcript factors which mediate the insulin response. A significant association between T-455C polymorphism and risk of CHD was found under dominant model. However, it should be noted that in the four studies evaluating T-455C polymorphism, only one study24 showed a significant association between T-455C polymorphism and CHD risk. So, more studies with large sample size are warranted to clarify this issue. For C-482T polymorphism, no significant association with CHD risk was found.

Different mechanisms could be linked to this finding. In previous works, T-455C polymorphism was associated with increased TG and ApoC3 levels.24 39 Also, T-455C polymorphism was demonstrated to be significantly associated with metabolic syndrome.39 Another study showed that T-455C polymorphism could interfere with n−3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on ApoC3 concentrations.7 Olivieri et al7 found that CC homozygous carriers were poorly responsive to the ApoC3 lowering effects of n−3 polyunsaturated fatty acids.

The present meta-analysis has several strengths. First, this study was based on the guidelines for conducting and reporting systematic reviews and the methods were rigorous. Second, we comprehensively evaluated the association between ApoC3 polymorphisms and CHD risk, and a total of four polymorphisms of ApoC3 were assessed. Besides, no publication bias was observed, indicating that the pooled results might be unbiased.

The current analysis also has several limitations. First, most of the included studies investigated Asian or Caucasian population, so the conclusions may not be true for other ethnic groups. Second, a significant heterogeneity was found and could not be completely explained when assessing some polymorphisms. Third, only PubMed, EMBASE and Cochrane library were searched for eligible articles. Finally, only articles published in English were included.

Some questions remain unanswered in the present study. Most of the studies did not report multivariable OR, so it is not clear whether ApoC3 polymorphisms could be an independent predictor of CHD risk or not. More studies are warranted to clarify this issue. Different genotyping assay methods were applied in the included studies, which might call for different results. And it should be noted that ApoC3 polymorphisms are non-modified risk factors, and little control methods over them were accessible. However, people in high-risk groups (such as S2 carriers of Sst I polymorphism) might be advised to go for regular checkups to reduce the risk of adverse cardiac event. Detecting ApoC3 polymorphisms may help people be aware of the risk of CHD. With the current level of evidence, we cannot comment on the optimal genotyping assay method and the cost-effectiveness of detecting ApoC3 polymorphisms. Further research is needed to explore the combination of variables associated with CHD risk to develop a predictive model with a high discriminative capacity.

In summary, ApoC3 Sst I and T-455C polymorphisms might be associated with CHD risk, while no evidence suggested a significant association between C-482T and C1100T polymorphisms and CHD risk.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: BL and YW contributed to conception, design of the study and editing the manuscript; YH and MZ contributed to the data acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data. JW contributed to the statistical analysis and editing the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Reference

- 1.Ross R. Atherosclerosis—an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med 1999;340:115–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jensen MK, Rimm EB, Rader D,et al. S447X variant of the lipoprotein lipase gene, lipids and risk of coronary heart disease in 3 prospective cohort studies. Am Heart J 2009;157:384–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nordestgaard BG, Benn M, Schnohr P, et al. Nonfasting triglycerides and risk of myocardial infarction, ischemic heart disease, and death in men and women. JAMA 2007;298:299–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Windler E, Havel RJ. Inhibitory effects of C apolipoproteins from rats and humans on the uptake of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and their remnants by the perfused rat liver. J Lipid Res 1985;26:556–65 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jong MC, Hofker MH, Havekes LM. Role of ApoCs in lipoprotein metabolism: functional differences between ApoC1, ApoC2, and ApoC3. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1999;19:472–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Azen SP, et al. Triglyceride- and cholesterol-rich lipoproteins have a differential effect on mild/moderate and severe lesion progression as assessed by quantitative coronary angiography in a controlled trial of lovastatin. Circulation 1994;90:42–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olivieri O, Martinelli N, Sandri M, et al. Apolipoprotein C-III, n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, and “insulin-resistant” T-455C APOC3 gene polymorphism in heart disease patients: example of gene-diet interaction. Clin Chem 2005;51:360–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tilly P, Sass C, Vincent-Viry M, et al. Biological and genetic determinants of serum apoC-III concentration: reference limits from the Stanislas Cohort. J Lipid Res 2003;44:430–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu J, Huang J, Liang Y, et al. Lack of association between apolipoprotein C3 gene polymorphisms and risk of coronary heart disease in a Han population in East China. Lipids Health Dis 2011;10:200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sediri Y, Kallel A, Feki M, et al. Association of a DNA polymorphism of the apolipoprotein AI-CIII-AIV gene cluster with myocardial infarction in a Tunisian population. Eur J Intern Med 2011;22:407–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhanushali AA, Das BR. Influence of genetic variants in the apolipoprotein A5 and C3 gene on lipids, lipoproteins, and its association with coronary artery disease in Indians. J Community Genet 2010;1:139–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abd El-Aziz TA, Mohamed RH, Hashem RM. Association of lipoprotein lipase and apolipoprotein C-III genes polymorphism with acute myocardial infarction in diabetic patients. Mol Cell Biochem 2011;354:141–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:264–9, W64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol 2010;25:603–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.AshokKumar M, Subhashini NG, SaiBabu R, et al. Genetic variants on apolipoprotein gene cluster influence triglycerides with a risk of coronary artery disease among Indians. Mol Biol Rep 2010;37:521–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muendlein A, Saely CH, Marte T, et al. Synergistic effects of the apolipoprotein E epsilon3/epsilon2/epsilon4, the cholesteryl ester transfer protein TaqIB, and the apolipoprotein C3–482 C>T polymorphisms on their association with coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis 2008;199:179–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martinelli N, Trabetti E, Bassi A, et al. The −1131 T>C and S19W APOA5 gene polymorphisms are associated with high levels of triglycerides and apolipoprotein C-III, but not with coronary artery disease: an angiographic study. Atherosclerosis 2007;191:409–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dallongeville J, Cottel D, Montaye M, et al. Impact of APOA5/A4/C3 genetic polymorphisms on lipid variables and cardiovascular disease risk in French men. Int J Cardiol 2006;106:152–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tobin MD, Braund PS, Burton PR, et al. Genotypes and haplotypes predisposing to myocardial infarction: a multilocus case-control study. Eur Heart J 2004;25:459–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu S, Song Y, Hu FB, et al. A prospective study of the APOA1 XmnI and APOC3 SstI polymorphisms in the APOA1/C3/A4 gene cluster and risk of incident myocardial infarction in men. Atherosclerosis 2004;177:119–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chhabra S, Narang R, Lakshmy R, et al. Apolipoprotein C3 SstI polymorphism in the risk assessment of CAD. Mol Cell Biochem 2004;259:59–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wong WM, Hawe E, Li LK, et al. Apolipoprotein AIV gene variant S347 is associated with increased risk of coronary heart disease and lower plasma apolipoprotein AIV levels. Circ Res 2003;92:969–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Izar MC, Fonseca FA, Ihara SS, et al. Risk Factors, biochemical markers, and genetic polymorphisms in early coronary artery disease. Arq Bras Cardiol 2003;80:379–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olivieri O, Stranieri C, Bassi A, et al. ApoC-III gene polymorphisms and risk of coronary artery disease. J Lipid Res 2002;43:1450–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Russo GT, Meigs JB, Cupples LA, et al. Association of the Sst-I polymorphism at the APOC3 gene locus with variations in lipid levels, lipoprotein subclass profiles and coronary heart disease risk: the Framingham offspring study. Atherosclerosis 2001;158:173–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wick U, Witt E, Engel W. Restriction fragment length polymorphisms at the apoprotein genes AI, CIII and B-100 and in the 5′ flanking region of the insulin gene as possible markers of coronary heart disease. Clin Genet 1995;47:184–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vavatsi NA, Kouidou SA, Geleris PNet al. Increased frequency of the rare PstI allele (P2) in a population of CAD patients in northern Greece. Clin Genet 1995;47:22–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rigoli L, Raimondo G, Di Benedetto A, et al. Apolipoprotein AI-CIII-AIV genetic polymorphisms and coronary heart disease in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Acta Diabetol 1995;32:251–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miettinen HE, Korpela K, Hamalainen L, et al. Polymorphisms of the apolipoprotein and angiotensin converting enzyme genes in young North Karelian patients with coronary heart disease. Hum Genet 1994;94:189–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kee F, Amouyel P, Fumeron F, et al. Lack of association between genetic variations of apo A-I-C-III-A-IV gene cluster and myocardial infarction in a sample of European male: ECTIM study. Atherosclerosis 1999;145:187–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sacks FM, Zheng C, Cohn JS. Complexities of plasma apolipoprotein C-III metabolism. J Lipid Res 2011;52:1067–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Onat A, Erginel-Unaltuna N, Coban N, et al. APOC3–482C>T polymorphism, circulating apolipoprotein C-III and smoking: interrelation and roles in predicting type-2 diabetes and coronary disease. Clin Biochem 2011;44:391–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olivieri O, Martinelli N, Girelli D, et al. Apolipoprotein C-III predicts cardiovascular mortality in severe coronary artery disease and is associated with an enhanced plasma thrombin generation. J Thromb Haemost 2010;8:463–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sacks FM, Alaupovic P, Moye LA, et al. VLDL, apolipoproteins B, CIII, and E, and risk of recurrent coronary events in the Cholesterol and Recurrent Events (CARE) trial. Circulation 2000;102:1886–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arai H, Yamamoto A, Matsuzawa Y, et al. Polymorphisms in four genes related to triglyceride and HDL-cholesterol levels in the general Japanese population in 2000. J Atheroscler Thromb 2005;12:240–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buzza M, Fripp Y, Mitchell RJ. Apolipoprotein AI and CIII gene polymorphisms and their association with lipid levels in Italian, Greek and Anglo-Irish populations of Australia. Ann Hum Biol 2001;28:481–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Corella D, Guillen M, Saiz C, et al. Associations of LPL and APOC3 gene polymorphisms on plasma lipids in a Mediterranean population: interaction with tobacco smoking and the APOE locus. J Lipid Res 2002;43:416–27 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perez-Martinez P, Gomez P, Paz E, et al. Interaction between smoking and the SstI polymorphism of the apo C-III gene determines plasma lipid response to diet. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2001;11:237–43 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Olivieri O, Bassi A, Stranieri C, et al. Apolipoprotein C-III, metabolic syndrome, and risk of coronary artery disease. J Lipid Res 2003;44:2374–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.