Abstract

Background

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Technology Appraisal Guidance on spinal cord stimulation (SCS) was published in 2008 and updated in 2012 with no change. This guidance recommends SCS as a cost-effective treatment for patients with neuropathic pain.

Objective

To assess the impact of NICE guidance by comparing SCS uptake in England pre-NICE (2008–2009) and post-NICE (2009–2012) guidance. We also compared the English SCS uptake rate with that of Belgium, the Netherlands, France and Germany.

Design

SCS implant data for England was obtained from the Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) database and compared with other European countries where comparable data were available.

Results

The HES data showed small increases in SCS implantation and replacement/revision procedures, and a large increase in SCS trials between 2008 and 2012. The increase in the total number of SCS procedures per million of population in England is driven primarily by revision/replacements and increased trial activity. Marked variability in SCS uptake at both health regions and primary care trust level was observed.

Conclusions

Despite the positive NICE recommendation for the routine use of SCS, we found no evidence of a significant impact on SCS uptake in England. Rates of SCS implantation in England are lower than many other European countries.

Keywords: PAIN MANAGEMENT

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study contributes a novel data analysis in the area of spinal cord stimulation, which highlights a lack of uptake of a cost-effective technology within the National Health Service (NHS).

Our findings are based on data extracted from the Hospital Episodes Statistics database which relies on hospital-coded data on procedures and indications.

Introduction

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) is a Department of Health (DH) funded arms-length body, established in 1999 to principally reduce ‘the postcode lottery’, that is the variation in the availability and quality of National Health Service (NHS) treatments and care in England and Wales.1 2 NICE publishes various types of guidance including Technology Appraisals (TA), Clinical Guidelines, Quality Standards and Interventional Procedures Guidance.2 The TA guidance is based on evaluations of clinical and cost-effectiveness of selected technologies. The NHS is legally obliged to provide funding for medicines and treatments recommended within 3 months of the guidance.1 In December 2011, the DH announced in its Innovation, Health and Wealth report that commissioners are expected to provide access to new treatments within 90 days of approval.1 3

The NICE TA guidance 159 on Spinal Cord Stimulation (SCS) for chronic pain of neuropathic or ischaemic origin was published in October 2008 and reviewed in January 2012 when no changes were made.4 This TA guidance approves SCS for adults with continued chronic neuropathic pain (measuring at least 50 mm on 0–100 mm visual analogue score) for at least 6 months despite all standard conventional treatment and after undergoing a successful trial of SCS by a multidisciplinary team.4

We examined the data for SCS uptake in England between 2008 and 2012 in order to assess the impact of NICE TA guidance implementation. We compared this to the SCS implant rate in other European countries. Data were also requested from all Primary Care Trusts (PCT) via a Freedom of Information request with regard to their SCS commissioning policy to determine whether a policy around the implementation of NICE guidance was in place or whether Individual Funding Requests (IFR) were being used.

Methods

Data for pre-NICE (2008–2009) and post-NICE (2009–2010; 2010–2011; 2011–2012) TA 159 publication for SCS procedural activity were obtained from the Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) database,5 using the QUANTIS system via NHiS.6 The HES is a national statistical data warehouse for England of the care provided by NHS hospitals. QUANTIS is a database of NHS and social care numerical data for the UK, and NHiS is a vendor that provides subscribed access to the QUANTIS database.

We examined OPCS-4 procedure codes A48.3 (implantation of neurostimulator adjacent to the spinal cord), A48.4 (attention to neurostimulator adjacent to the spinal cord) and A48.7 (insertion of neurostimulator electrodes into the spinal cord). The OPCS code A48.3 was assumed to reflect new permanent SCS implants, code A48.4 to contain both replacements and revisions, and code A48.7 to represent trial procedures. OPCS code 48.4 does not allow for a clear differentiation between battery replacement and revisions.

The relevant SCS codes were filtered by indication to ensure that only back pain and spinal indications were included. This eliminated any inclusion of other types of neurostimulation that may have been miscoded, for example, for bowel and bladder indications. SCS uptake results are expressed per million populations across each Strategic Health Authority regions in England. We also compared uptake rates across PCT.

Oracle (11g Database) and Excel (Microsoft Office 2010 Pro) software programs were utilised for the data analysis. We compared English SCS uptake data from 2011 to 2012 (code A48.3 only) with European countries where we were able to source the appropriate equivalent data, that is France, Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands.7

Results

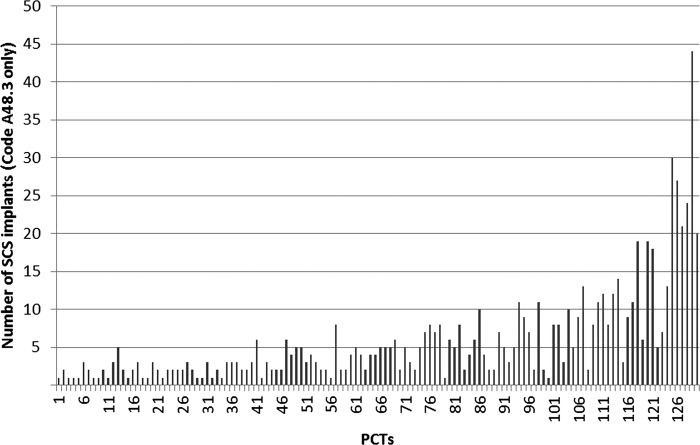

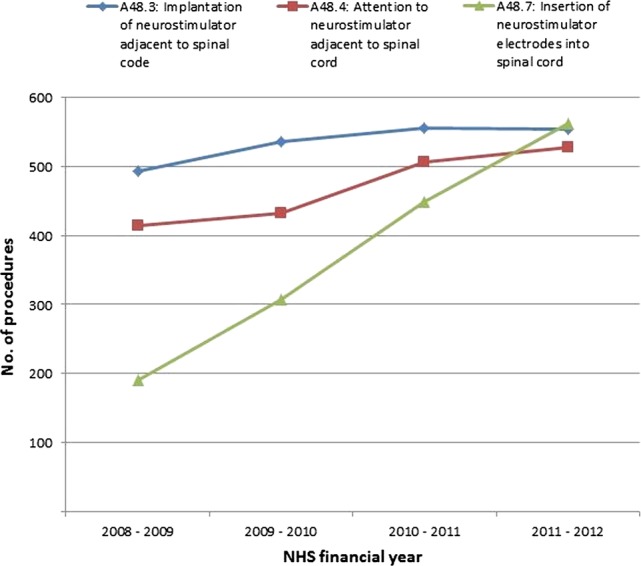

The HES data analysis for the year 2008–2012 showed a small increase in procedure codes 48.3 and 48.4 (table 1) and large increase in procedure code 48.7. Figure 1 illustrates the activity trends for each separate procedure code. On analysis of each of the procedure codes, the increase in SCS procedures appears to be driven primarily by replacements, revisions and a large increase in trial activity. There was considerable variation in the rate of SCS uptake across Strategic Health Authorities throughout this time horizon. The breakdown of the number of SCS procedures funded by PCTs in 2011–2012 is shown in figure 2, indicating considerable inequity of patient access to this NICE-approved treatment.

Table 1.

Total number of SCS procedures (combined A48.3 and A48.4 OPCS procedures) from 2008 to 2012

| 2008–2009 |

2009–2010 |

2010–2011 |

2011–2012 |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regional SHA | Population | Number of cases | Cases/million | 95% CI | Number of cases | Cases/million | 95% CI | Number of cases | Cases/million | 95% CI | Number of cases | Cases/million | 95% CI |

| East Midlands | 4 380 276 | 25 | 5.7 | 4 to 8 | 53 | 12.1 | 9 to 15 | 56 | 12.8 | 10 to 16 | 75 | 17.1 | 14 to 21 |

| East of England | 5 714 218 | 137 | 24.0 | 21 to 28 | 175 | 30.6 | 27 to 34 | 205 | 35.9 | 32 to 40 | 170 | 29.8 | 26 to 34 |

| London | 7 757 619 | 83 | 10.7 | 9 to 13 | 60 | 7.7 | 6 to 10 | 81 | 10.4 | 8 to 13 | 73 | 9.4 | 8 to 12 |

| North East | 2 577 541 | 136 | 52.8 | 47 to 59 | 120 | 46.6 | 41 to 53 | 95 | 36.9 | 31 to 43 | 112 | 43.5 | 38 to 50 |

| North West | 6 923 825 | 132 | 19.1 | 16 to 22 | 155 | 22.4 | 19 to 26 | 169 | 24.4 | 21 to 28 | 173 | 25.0 | 22 to 28 |

| South Central | 4 069 352 | 20 | 4.9 | 3 to 7 | 39 | 9.6 | 7 to 13 | 44 | 10.8 | 8 to 14 | 38 | 9.3 | 7 to 13 |

| South East Coast | 4 302 298 | 92 | 21.4 | 18 to 26 | 81 | 18.8 | 15 to 23 | 106 | 24.6 | 21 to 29 | 108 | 25.1 | 21 to 29 |

| South West | 5 181 449 | 109 | 21.0 | 18 to 25 | 99 | 19.1 | 16 to 23 | 88 | 17.0 | 14 to 20 | 116 | 22.4 | 19 to 26 |

| West Midlands | 5 421 595 | 50 | 9.2 | 7 to 12 | 53 | 9.8 | 8 to 13 | 45 | 8.3 | 6 to 11 | 43 | 7.9 | 6 to 11 |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 5 244 956 | 123 | 23.5 | 20 to 27 | 133 | 25.4 | 22 to 29 | 172 | 32.8 | 29 to 37 | 174 | 33.2 | 29 to 37 |

| Total | 51 573 129 | 907 | 17.6 | 17 to 19 | 968 | 18.8 | 18 to 20 | 1061 | 20.6 | 19 to 22 | 1082 | 21.0 | 20 to 22 |

SAS, spinal cord stimulation; SHA, Strategic Health Authority.

Figure 1.

Breakdown of spinal cord stimulation procedural activity trends (procedure codes A48.3, A48.4 and A48.7).

Figure 2.

Number of total spinal cord stimulation procedures per Primary Care Trusts in 2011–2012.

Table 2 compares the available European data against procedure code 48.3, reflecting the number of new SCS implants only. In France there was a small increase in the number of SCS implants per million of population for the period 2008–2010 (table 2). The rate of uptake of SCS per million of population in England is the lowest compared with these other European countries (table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of new SCS implants in the UK (procedure code A48.3 only) against other European countries per year

| Yearly SCS/million |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 |

| Belgium | 84.6 | |||

| France | 9.19 | 8.17 | 11.35 | |

| The Netherlands | 54.3 | |||

| Germany | 11.7 | |||

| UK (England) | 11 | 10.7 | ||

SAS, spinal cord stimulation; SCS, spinal cord stimulation.

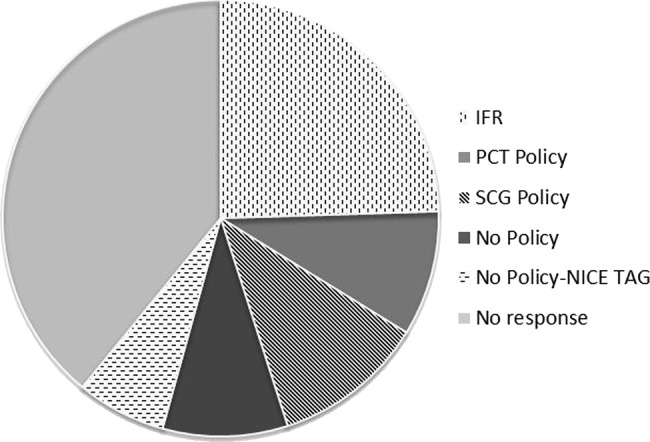

Figure 3 shows requested data from all PCT with regard to their SCS commissioning policy via a Freedom of Information request. The response rate was 60.9%, with 40.2% of PCTs requiring IFR, 18.5% following a Specialised Commissioning Group (SCG) policy, 15.2% following either PCT policy or with no active policy, and only 10.8% following the NICE TA Guidance allowing automatic funding. While the level of data did not allow a statistical analysis of the correlation between the PCT policy status and the number of SCS procedures funded, some evidence of an association between regions with an existing policy and the number of patients being funded for SCS was apparent. For example, across Yorkshire and the Humber, where a clear SCG policy was being followed by the collective PCTs, a high rate of SCS procedures was observed at 33.2 cases per million (table 1). This was also evident with the East of England (29.8 procedures per million). Conversely, the lowest rates of SCS referrals were reported in regions with no PCT or SCG policy in place, such as the West Midlands and London (7.9 and 9.4 procedures per million, respectively).

Figure 3.

Data from Freedom of Information request regarding Primary Care Trusts policies on spinal cord stimulation (data accessed 2011).

Discussion

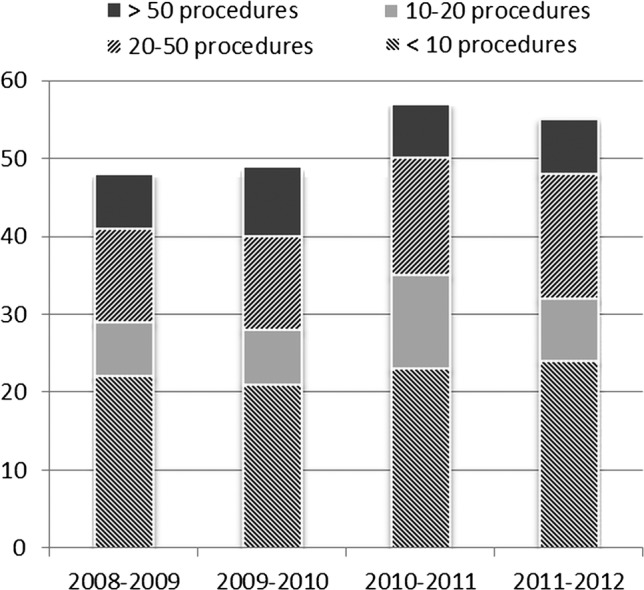

The NHS has a mandatory duty to fund and provide NICE-approved treatments recommended within a NICE TA within 90 days. However, our UK data analysis from 2008 to 2012 shows that the NICE TA 159 had a small impact on uptake of SCS in neuropathic pain. Although an increase of 19.3% in SCS procedures was observed over the 4-year period, figure 4 includes battery replacements and revisions in addition to new SCS permanent implants. When new SCS implants are considered alone, an increase in uptake of only 12.4% was observed between 2008 and 2012 (figure 1), despite the NICE TA 159 advocating a 10% increase in uptake each year. Interestingly the substantial rise in procedure code 48.7 (trial procedures) does not appear to convert into a comparable increase in permanent SCS procedures. Given that the conversion rate of trial to permanent SCS implants is generally consistent at around 75–80%,8 accuracy in provider coding in this instance may be questioned.

Figure 4.

Number of spinal cord stimulation implanting centres year-on-year.

There remains a considerable regional inequality in patient access to this NICE approved treatment. The Right Care9 is one of the national work streams in the DH Quality Innovation Productivity and Prevention programme which identifies unwarranted variation in NHS treatments based on geographical areas.9 10 One of the Right Care objectives for 2011–2012 is to minimise this unwarranted variation and maximise value.9 Value can be increased by improving quality, optimising resource utilisation and ensuring that patients receive appropriate interventions.

Our findings are in contrast with a NICE implementation report11 that shows a generally effective impact of guidance for surgical procedures. For example, laparoscopic colorectal surgeries occurred at higher rate than forecasted by NICE (TA 105).12 Laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair uptake increased following guidance, but it stabilised at lower levels than that NICE forecasted (TA 83).13 In addition, there was overall increase in bariatric surgery for morbid obesity following NICE guidance (CG 43).14 Our study provides data on the marked variability in rate of SCS uptake at both health authority and PCT level.

NICE assessed SCS as a highly cost-effective treatment for failed back surgery syndrome with an incremental £10 480 per quality adjusted life year (QALY) ratio compared with conventional medical management alone, and £9219 per QALY gained when compared with repeat back operation.4 These ratios are considerably below the UK willingness to pay threshold of £20 000 to 30 000 per QALY.

Despite mandatory TA guidance on SCS, the majority of PCTs required IFR for each patient (figure 3). Some PCTs rated SCS as a low priority procedure. The reasons for the barriers to funding are multifactorial and include lack of awareness of SCS referral guidelines, lack of NICE TAG enforcement at regional and national level, as well as a limitation of clinical capacity at implanting centres. Owing to the limitations of the available data, it is not possible to disentangle the factors responsible for the continuing inequity of funding for SCS implants. Yet we can comment that there has been no significant increase in the number of implanting centres. The capacity within existing centres is not showing a growth curve as expected in response to the NICE guidance. Only 10.8% of PCTs implemented NICE guidance as a funding policy (figure 3). It is possible that piecemeal funding and the difficulties associated with such an approach, as well as the impact of the marked regional variations, have prevented the expansion of current providers. The reported incidence of failed back surgery syndrome is estimated as 10–40% of patients undergoing back surgery.15 In a recent survey of the UK, 53% of pain clinics estimated 10% of their referrals comprising failed back surgery syndrome patients and the remaining 47% of pain clinics estimated it as 20–30% of their referrals, therefore lack of candidates is unlikely.16

In a comparison to France, Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands, England has the lowest rate of implants per million of the population. Smaller countries show a much higher rate of SCS implants,7 with Belgium and the Netherlands implanting 84.6 and 54.3 per million of population, respectively. Nevertheless, for Belgium and the Netherlands only 1 year data are available; therefore, we are unable to comment on trends. Data for France were available for the past 3 years (table 2) which show no significant increase in SCS implants. The main indications for SCS are similar across the four countries, that is failed back surgery syndrome or radicular pain, phantom pain, peripheral nerve injury, traumatic brachial plexus injury, spinal lesion, diabetic polyneuropathy and postherpetic neuralgia.7 Focusing on the most common indication for SCS of failed back surgery syndrome, it is estimated that 10–40% of patients undergoing spinal surgery will develop neuropathic pain.15 According to the HES database, the number of spinal surgery procedures in England in 2009–2010 was 117 803.17 Assuming that one-third of these procedures is being carried out for pain, the annual estimate will be 78 533 procedures of which 10–40% (7853–31 414) would be expected to be eligible for SCS treatment.16 Based on these data, less than 2% of the eligible population of neuropathic patients in England are currently receiving SCS treatment. A lack of awareness of SCS as a clinical and cost-effective treatment option among referring physicians may be hindering the uptake of this NICE-approved technology. More constructive engagement with the wider population of patients and referring physicians by the neuromodulation community are warranted to ensure appropriate and early referral for SCS therapy.

Conclusion

Our study shows that the NICE TA 159 has had negligible impact on the uptake of SCS for new patients, and rates of SCS implantation were highly variable across Strategic Health Authorities and PCTs. The reasons for the lack of impact appear to be multifactorial and may include limited awareness of SCS as a clinical and cost-effective treatment option among the wider referral community. Within the new arrangements of NHS England, where SCS is deemed to be a prescribed specialised service that will be commissioned centrally, some of these barriers may be addressed including a shift towards more equitable access to this technology, and elimination of the use of IFRs. Future implementation of NICE Innovation Scorecards to track compliance with NICE TA and other NICE compliance initiatives may further help to reinforce and track the implementation of NICE guidance.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors had an integral role in producing this manuscript and have made substantial contributions to the analysis and interpretation of data, drafting and revision of the article and approving the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: Access to the QUANTIS database to extract the relevant Hospital Episode Statistics data was funded by Medtronic UK.

Competing interests: RST is a paid consultant for Medtronic Inc. Sam Eldabe has previously undertaken consulting work for Medtronic Inc.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Readers are invited to contact NH, if they wish to request any raw unpublished Hospital Episodes Statistics data pertaining to the manuscript.

References

- 1.Sorenson C, Drummond M, Kanavos P, et al. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE): how does it work and what are the implications for the U.S.? 2008. (updated April 2008). http://www.npcnow.org/issuearea/ebm.asp.

- 2.NICE. How we work (updated 13 July 2012). http://www.nice.org.uk/aboutnice/howwework/how_we_work.jsp.

- 3.DOH. Creating change: innovating health and wealth one year on. Health Do, 2011

- 4.NICE. Technology Appraisal Guidelines 159: spinal cord stimulation for chronic pain of neuropathic or ischaemic origin, 2008. (updated Oct 2008). http://www.nice.org.uk/TA159

- 5.Hospital Episode Statistics (cited 2013) http://www.hesonline.nhs.uk/

- 6.NHiS. http://www.nhis.info/

- 7.Camberlin C, San Miguel L, Smit Y, et al. KCE Report 189C: Health Technology Assessment. Neuromodulation for the management of chronic pain: implanted spinal cord stimulators and intrathecal analgesic delivery pumps. In: Centre BHCK, editor. Brussels, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 8.North RB. SCS trial duration. Neuromodulation 2003;6:4–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.NHS Rightcare 2013 (updated 2013) http://www.rightcare.nhs.uk/resources.

- 10.NHS Rightcare Atlas 2013 (cited 4 April 2013) http://www.rightcare.nhs.uk/atlas.

- 11.N.I.C.E. NICE implementation programme, 2012. (updated 14 November 2012). http://www.nice.org.uk/usingguidance/niceimplementationprogramme/nice_implementation_programme.jsp

- 12.NICE. NICE implemention uptake report: laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer. NICE Technology Appraisal 105. Excellence NIoHaC, ed. 2010

- 13.NICE. Laparoscopic surgery for inguinal hernia repair: implementation uptake report. Technology appraisal 83. Excellence NIfHaC, ed. 2004

- 14.N.I.C.E. Obesity guidance on the prevention, identification, assessment and management of overweight and obesity in adults and children. Clinical Guidance CG43. Excellence NIfHaC, ed. 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomson S, Jacques L. Demographic characteristics of patients with severe neuropathic pain secondary to failed back surgery syndrome. Pain Pract 2009;9:206–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tharmanathan P, Adamson J, Ashby R, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of failed back surgery syndrome in the UK: mapping of practice using a cross-sectional survey. Br J Pain 2012;6:142–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mailis-Gagnon A, Furlan AD, Sandoval JA, et al. Spinal cord stimulation for chronic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;(3):CD003783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.