Abstract

Objectives

To compare collagenase injections and surgery (fasciectomy) for Dupuytren's contracture (DC) regarding actual total direct treatment costs and short-term outcomes.

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting

Orthopaedic department of a regional hospital in Sweden.

Participants

Patients aged 65 years or older with previously untreated DC of 30° or greater in the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) and/or proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints of the small, ring or middle finger. The collagenase group comprised 16 consecutive patients treated during the first 6 months following the introduction of collagenase as treatment for DC at the study centre. The controls were 16 patients randomly selected among those operated on with fasciectomy at the same centre during the preceding 3 years.

Interventions

Treatment with collagenase was given during two standard outpatient clinic visits (injection of 0.9 mg, distributed at multiple sites in a palpable cord, and next-day finger extension under local anaesthesia) followed by night-time splinting. Fasciectomy was carried out in the operating room (day surgery) under general or regional anaesthesia using standard technique, followed by therapy and splinting.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Actual total direct costs (salaries of all medical personnel involved in care, medications, materials and other relevant costs), and total MCP and PIP extension deficit (degrees) measured by hand therapists at 6–12 weeks after the treatment.

Results

Collagenase injection required fewer hospital outpatient visits to a therapist and nurse than fasciectomy. Total treatment cost for collagenase injection was US$1418.04 and for fasciectomy US$2102.56. The post-treatment median (IQR) total extension deficit was 10 (0–30) for the collagenase group and 10 (0–34) for the fasciectomy group.

Conclusions

Treatment of DC with one collagenase injection costs 33% less than fasciectomy with equivalent efficacy at 6 weeks regarding reduction in contracture.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study presents previously unknown estimates of the actual costs of treating Dupuytren's contracture with collagenase injections or fasciectomy.

Comparison of the actual costs of the two treatments was based on detailed definition and measurement of all relevant costs.

Outcomes of injections were prospectively measured but outcomes of surgery were based on medical records.

Costs may vary across countries.

Only short-term outcomes (6 weeks) were compared.

Introduction

Dupuytren's contracture (DC) is a common hand disorder causing finger contractures that may compromise hand function. Surgery in the form of limited fasciectomy has been the main treatment option for reducing the contracture.1 In Sweden (population 9.5 millions), more than 3000 fasciectomy procedures are performed annually2; the actual number is probably higher because procedures performed by surgeons in private practice, although constituting a small proportion,3 may not always be reported to the national database. Surgery is usually carried out in the main operating room (OR) under general or regional anaesthesia and the operating time is, on an average, about 1 h,4 but can be substantially longer when severe contractures are present in multiple fingers. After surgery, many patients require therapy and splints. Although surgery is often effective in reducing the contracture, postoperative complications such as nerve injury and wound healing problems are common and patients may develop contracture recurrence.5 6

Recently, injection with collagenase Clostridium histolyticum (CCH) has been introduced as the first pharmacological treatment for DC after it was shown in a randomised controlled trial to be more effective than placebo injections in reducing contractures.7 The treatment is a relatively simple procedure given in the outpatient clinic and rarely requires a prolonged therapy. The current price of a CCH injection (in Sweden) is almost US$1000 and one injection is used for each finger involved (unless contractures in 2 fingers are caused by a common cord). Owing to the economic pressure to control healthcare expenditures, the cost-effectiveness of surgical procedures has gained an increased significance in hospital decision-making. The cost analysis of different treatment procedures such as fasciectomy and injection is therefore essential and the differences in short-term costs associated with these two techniques are important to consider.

To our knowledge, no previous study has compared the actual costs of CCH injections with those of fasciectomy. One study based on a cost-utility analysis model concluded that open partial fasciectomy did not meet the cost-effectiveness threshold and that CCH injections would be cost-effective when priced below US$945.8 Studies concerning costs of surgery have usually used reimbursement as a measure of costs,9 but reimbursement does not necessarily reflect the actual cost of a procedure. Reimbursement levels for a certain procedure may vary substantially across and even within countries. For cost comparison of CCH injections and fasciectomy in DC, the actual cost of each procedure is therefore a more relevant measure. When comparing the costs of two treatment methods, the outcome of the treatments must also be taken into consideration. However, we could not find studies that have compared the outcomes of CCH and fasciectomy.

The main aim of this retrospective cohort study was to compare CCH injections with fasciectomy regarding the actual total direct treatment costs. The secondary aim was to compare the short-term outcomes of these two treatment methods.

Patients and methods

Study participants

We conducted a retrospective cohort study at one orthopaedic department (Hässleholm, Kristianstad and Ystad Hospitals) in southern Sweden. The department is the only centre that treats patients with DC in a region with approximately 300 000 inhabitants.

Data on CCH injections were collected prospectively starting September 2011 when CCH was introduced as the main treatment option for DC at the department. The indication for treatment with CCH injections was identical to that previously used for surgery at the study centre, namely a palpable cord and contracture of 30° or greater in the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) and/or proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints. For this study, we included the first 16 consecutive patients, aged 65 years or older, treated with CCH injections during the first 6 months (September 2011 through February 2012). We restricted the study to patients of non-working age because we aimed to compare only direct costs.

Data on fasciectomy were extracted from the medical records of patients treated at the department before the introduction of CCH injections. The patients were chosen among those aged 65 years or older, operated on with fasciectomy from January 2009 through June 2011. Patients with surgery on more than two fingers, previous surgery for DC in the same hand and additional procedures performed (eg, skin graft or amputation) were excluded. A total of 113 patients were potentially eligible. Of these, a random sample of 15% was chosen by computer (statistical software), yielding 18 patients; 2 were excluded (1 had surgery for DC in the thumb and 1 chose to have postoperative therapy at another location). Thus, the fasciectomy group included 16 patients.

Treatment and follow-up procedures

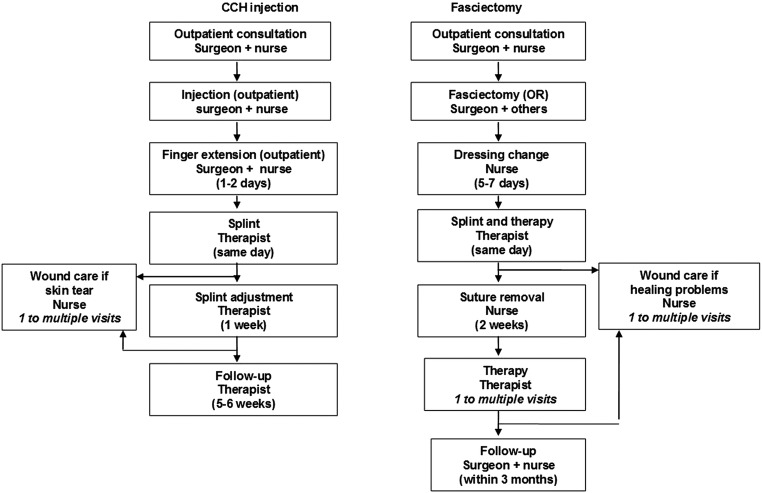

Both treatments required an initial standard outpatient consultation visit to a hand surgeon or an orthopaedic surgeon, usually as a referral from the patient's general practitioner. Each surgeon was assisted by a nurse at the outpatient clinic. During the visit, the treatment decision was made and the patient was scheduled for treatment (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Diagram showing the various stages of treating patients with Dupuytren's contracture with collagenase Clostridium histolyticum (CCH) injection or with fasciectomy as a day-surgery procedure performed in the operating room (OR). The number of visits is one unless specified otherwise.

Collagenase injection

Treatment with CCH required two standard outpatient visits to a hand surgeon: injection and next-day finger extension.7 During these visits the surgeon was assisted by a nurse (all treatments were given by the same hand surgeon). A modified injection method was used for all treated fingers; after reconstituting CCH with 0.39 mL of diluent, according to the standard procedure, all the reconstituted CCH (0.9 mg) was injected into the cord, distributed at multiple sites. The following day, finger manipulation (extension) was carried out under local anaesthesia. Immediately after finger extension, the patient met the therapist and received a splint for use at night for 8 weeks. A second visit to the therapist was carried out 1-week postinjection for splint adjustment and therapy instructions. Patients who during the finger extension developed a skin tear that was judged to require dressing change were asked to visit a nurse within 2–3 days. Further visits to the nurse were carried out when necessary, depending on wound status. No routine post-treatment visits were scheduled to the treating surgeon and the final follow-up (usually at 5–6 weeks) was carried out by the therapist. If the patient was not satisfied with the degree of correction after the first injection, the therapist arranged a consultation to the treating surgeon for consideration of further treatment.

Fasciectomy

Fasciectomy was carried out as a day-surgery procedure in the main OR. The surgery was carried out by one of six different surgeons (three experienced hand surgeons and three orthopaedic surgeons with experience in hand surgery) using standard technique for limited open fasciectomy.10 General anaesthesia or axillary block was used. According to routine procedures at the hospital, general anaesthesia was administered by a nurse anaesthetist and axillary block was administered by an anaesthesiologist, after which the nurse anaesthetist was in charge of the patient's care with anaesthesiologist help obtained when needed. The surgery was carried out by a surgeon (no assistant) with a team consisting of an OR nurse, a nurse anaesthetist and two nurse assistants (1 participated only in the initial preparations). The electronic records for each surgical procedure include the exact start and finish times for the preparations before surgery, anaesthesia, the actual surgery (ie, operating time from incision to dressing) and the work carried out after the surgeon has completed the operation and until the patient is taken back to the recovery room. After returning from the OR, the patient stayed in the recovery room until discharge from the day-surgery unit. The time of discharge is documented in the electronic records. Thus, for each patient, three times were recorded: the operating time, the total OR time (from start of preparations until room ready for next procedure) and the time at the recovery room until discharge.

About 5–7 days after fasciectomy, all the patients visited a nurse for dressing change, followed immediately by a visit to a therapist for a splint and therapy instructions. A second visit to the nurse for wound inspection and suture removal was carried out at approximately 2 weeks. Further visits to the nurse were carried out when necessary, depending on wound status. Patients also had further visits to the therapist for scar management, splint adjustments and therapy instructions as required. The treating therapist decided on the frequency and duration of therapy. Patients had one postoperative follow-up visit to the surgeon, timed according to surgeon preference.

Cost measurement

A detailed analysis of the salaries of physicians and non-physician medical personnel involved in the treatment of patients with DC was performed for CCH injection and fasciectomy. We identified the average salaries of individuals and used the average time units to calculate the cost of manpower. The costs of all materials, premises and other costs were calculated. We included fixed assets such as the costs of the premises and its expenses and the costs of surgical equipment. All costs were measured based on 2011 salaries/prices. These costs include salaries of all medical personnel involved in the direct care of the patients including social security contributions, vacation pay and sick pay (averaged for each category: specialist orthopaedic surgeon, anaesthesiologist, nurse, nurse assistant and therapist), hospital overhead costs, the degree of capacity utilisation, medications, surgical and other material, premises and other costs. The average salaries were based on all respective medical personnel group in the public healthcare sector in the region. We did not include the costs of non-medical personnel involved in the care (such as receptionists, secretaries, cleaners, etc).

A standard outpatient visit to a doctor was 20 min. For the two CCH visits (injection and finger extension), we used the standard time for the surgeon and 25 min for the assisting nurse (to account for the time needed for preparations and work after the session had ended). For fasciectomy, we used the mean operating time, total OR time and recovery time, according to the personnel involved and adjusted as required. For the operating surgeon, we used the mean operating time plus 25 min needed for additional work (assessing the patient and marking the surgical site before surgery, scrubbing, writing the surgical notes and discharging the patient after surgery). For the non-physician personnel, we used the mean total OR time, and for the anaesthesiologist, we used half that time (1 anaesthesiologist is usually assigned to 2 ORs simultaneously and the care of these patients after surgery). For recovery room personnel (a nurse and a nurse assistant are in charge of up to 5 patients simultaneously), we used a fifth of the recovery time plus 5 min (preoperative preparations). A standard outpatient visit to a nurse (for wound care after CCH injection or fasciectomy) was 45 min. A standard visit to therapist after CCH injection was 30 min and after fasciectomy was 45 min. For each patient, the exact number of hospital outpatient visits to a doctor, nurse or therapist, related to the treatments, was retrieved from the Patient Administrative System.

Outcome measurement

At baseline and at all follow-up visits, range of motion including extension and flexion of the MCP and PIP joints of the fingers was measured with a goniometer. In the fasciectomy group, the baseline measurements were carried out by the surgeons during the visit that resulted in the patient being scheduled for fasciectomy and the post-treatment measurements were carried out by six different therapists; these measurements were recorded in the patient's electronic medical records. In the CCH group, all the measurements (immediately before injection and at follow-up) were carried out by the same therapist, as part of a research project. The measurements recorded at baseline and at the final visit were used in the analysis.

Analysis

In two previous randomised trials, the proportion of MCP joints that were reduced to 0–5° of extension deficit was 45% at 30 days after first CCH injection7 and 94% at 6 weeks after fasciectomy.11 To detect a difference of this magnitude between the two groups (80% power and 0.05 significance level) would require a sample of 13 patients in each group. The cost estimation of CCH was based on standard procedures independent of sample size. For the cost of fasciectomy, a random sample of 15% from 113 fasciectomy-treated patients was judged adequate to provide representative average procedure time estimates and the number of visits to medical personnel, on which the total cost was based. Data are shown as mean and SD and/or median and IQR. We calculated the average total cost of treatment per patient when only one CCH injection is given. We also calculated the cost if 20% of the patients would need two CCH injections given on separate sessions to obtain a satisfactory contracture reduction. As some patients who developed skin tears during finger extension chose to have dressing change, when necessary, at home or at primary care, only one nurse visit was recorded in the Patient Administrative System. We therefore made the calculations assuming one of three patients in the CCH group would require one nurse visit. We also conducted a sensitivity analysis with the conservative assumption of one nurse visit per patient. All costs were calculated in Swedish Kronor (SEK) and converted to USD using the rate of US$1=6.676 SEK (Sweden's Central Bank average for 2011). The within-group change in extension deficit was analysed with the Wilcoxon test. We also compared the two groups with regard to improvement in total extension deficit using the Mann-Whitney test. A p value below 0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance.

Results

The 16 patients in the CCH group and the 16 patients in the fasciectomy group had similar characteristics (table 1). In the fasciectomy group, half of the patients received general anaesthesia and the other half axillary block. The mean operating time was 62 (SD 27) min, mean total OR time was 138 (SD 43) min and mean postoperative time spent at the day-surgery recovery room until discharge was 215 (SD 41) min. The median time from surgery to end of therapy was 6.3 weeks (IQR 4–11.5) and to the postoperative follow-up by the surgeon was 7.5 weeks (IQR 6–12). None of the patients in the CCH group required further therapy than the standard visits. Of the 16 patients, 9 developed skin tears ranging from minor superficial skin breakage that did not require further wound care to deeper wound that required one or more dressing changes. All the wounds had healed within 2 weeks after injection.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the two samples of patients with Dupuytren's contracture treated with CCH injection or surgery (fasciectomy)

| CCH injection | Fasciectomy | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients (men) | 16 (11) | 16 (13) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 69 (4) | 71 (5) |

| Number of fingers treated* | ||

| Small | 11 | 9 |

| Ring | 7 | 8 |

| Middle | 0 | 1 |

| Extension deficit (degrees) | ||

| Total† | ||

| Mean (SD) | 90 (39) | 71 (28) |

| Median (IQR) | 70 (60–115) | 75 (45–89) |

| MCP‡ | ||

| Mean (SD) | 64 (16) | 60 (17) |

| Median (IQR) | 65 (60–75) | 60 (41–80) |

| PIP‡ | ||

| Mean (SD) | 55 (22) | 46 (18) |

| Median (IQR) | 55 (43–70) | 40 (35–48) |

*Two patients in each group had two fingers treated.

†MCP plus PIP joints in all treated fingers (in patients with 2 fingers treated the finger with largest extension deficit was used).

‡The values showing MCP and PIP extension deficits separately include only joints with contracture (no MCP contracture in 1 patient in the CCH group and 2 patients in the fasciectomy group and no PIP contracture in 7 patients in each group).

CCH, collagenase Clostridium histolyticum; MCP, metacarpophalangeal; PIP, proximal interphalangeal.

Costs

The cost specifications for the two treatments are shown in table 2. The largest treatment cost for CCH injections was the cost of the injection itself (US$970.19), and for fasciectomy, the cost of personnel (US$783.97) and other costs (US$380.81) associated with the surgery in the OR. Compared with fasciectomy, treatment with CCH injections required fewer outpatient hospital visits to a nurse and a therapist (table 3).

Table 2.

Cost specification for the various stages of treating Dupuytren's contracture with CCH injection or surgery (fasciectomy)

| Personnel costs* (US$) | Other costs† (US$) | |

|---|---|---|

| Doctor visit, CCH or fasciectomy (doctor and nurse) | 65.80 | 16.78 |

| Injection, CCH (doctor and nurse) | 70.63 | 991.16 |

| Finger extension, CCH (doctor and nurse) | 70.63 | 20.97 |

| Therapist visit, CCH | 26.58 | 25.16 |

| Surgery, fasciectomy (doctors and others) | 783.97 | 380.81 |

| Day surgery care, fasciectomy | 88.10 | 52.41 |

| Therapist visit, fasciectomy | 39.88 | 37.77 |

| Nurse visit, CCH or fasciectomy | 43.51 | 37.77 |

Price of 1 CCH injection=US$970.19.

*Include average salary, social security contributions, vacation pay, sick pay, overhead costs and the degree of capacity utilisation.

†Include costs of surgical and other materials, injections, premises, etc.

CCH, collagenase Clostridium histolyticum.

Table 3.

Number of visits to medical personnel, actual costs and short-term outcomes of treating Dupuytren's contracture with injection or surgery (fasciectomy)

| CCH injection | Fasciectomy | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean, median (IQR) number of visits to | ||

| Doctor | 3* | 2* |

| Nurse | 0.33* | 3.0, 3.0 (2.0–3.8) |

| Therapist | 3* | 5.1, 4.0 (3.0–6.8) |

| Total cost per patient (US$) | 1418.04 | 2102.56 |

| Total cost per patient when 20% require two injections (US$) | 1675.24 | 2102.56 |

| Extension deficit (degrees)† | ||

| Total | ||

| Mean (SD) | 20 (25) | 19 (19) |

| Median (IQR) | 10 (0–30) | 10 (0–34) |

| MCP | ||

| Mean (SD) | 10 (17) | 8 (10) |

| Median (IQR) | 0 (0–15) | 0 (0–20) |

| PIP | ||

| Mean (SD) | 23 (18) | 21 (13) |

| Median (IQR) | 20 (8–35) | 25 (8–33) |

*The number of visits to a doctor in both groups and to a therapist in the CCH group was similar for all patients (figure 1); one-third of CCH patients assumed to require one visit to a nurse.

†MCP plus PIP joints in all treated fingers. The values showing MCP and PIP extension deficits separately include only joints with pretreatment contracture (see footnote in table 1).

CCH, collagenase Clostridium histolyticum; MCP, metacarpophalangeal; PIP, proximal interphalangeal.

The total treatment cost with one CCH injection was 33% lower than that for fasciectomy (US$1418.04 vs US$2102.56). The cost was still lower (US$1675.24) if 20% of patients treated with CCH would require two injections in the same hand, given in separate sessions. In the sensitivity analysis, the cost of CCH injections assuming an average of one nurse visit per patient was US$1472.51 when one injection is given and US$1696.79 when 20% would require two injections.

Outcomes

Of the 16 patients in the CCH and fasciectomy groups, 7 and 9 patients, respectively, achieved an extension deficit of 0–5° in the joint with the largest extension deficit. In both groups, the improvement in total extension deficit was statistically significant (p<0.001) and the extension deficits after CCH and fasciectomy were similar (median 10°; table 3). The median improvement in total extension deficit in the CCH group was 65 (IQR 56–81) degrees and in the fasciectomy group was 50 (IQR 41–60) degrees (p=0.007).

No complications were observed in any of the groups at the final follow-up.

Discussion

Our study shows that treatment of DC with a single collagenase injection is associated with lower costs than surgery (fasciectomy) and the short-term outcomes (6 weeks) regarding reduction in finger joint contractures are similar. The costs are still lower when assuming that 20% of the patients would require two injections in the same hand, but if more than 5 of 10 patients need two injections, the costs would exceed those of fasciectomy. Our estimates of the costs assuming 20% would require two injections were based on separate treatment sessions; the costs would be even lower if the two injections are given in the same session, which would probably become the usual practice.12 Furthermore, our results should be considered conservative since we have not considered complications (such as wound infection and chronic regional pain syndrome) that are probably more frequent after surgery than after CCH injections and would therefore add to the total costs. The study by Hurst et al7 reported use of an average of about two CCH injections per patient. However, in that study, finger extension, which often is a painful procedure, was carried out without anaesthesia, which may have reduced the degree of initial contracture correction and thus necessitating a second injection. As in our study, use of local anaesthesia is currently the standard procedure. In addition, Hurst et al injected 0.58 mg CCH into one part of the cord whereas our technique is to inject the whole content of a single CCH injection (0.9 mg) into the cord at multiple sites, which would probably increase the efficacy of a single injection.

For fasciectomy, the largest cost was represented by the various costs associated with a day-surgery procedure of approximately 1 h duration in the OR. The cost would be lower if the average operating time was shorter than our estimate of 62 min. In a recent study of DC in 12 European countries (based on a surgeon survey and patient chart review), the mean operating time for fasciectomy across all countries was 67 min (Nordic 63, Eastern 69, Western 66 and Mediterranean 68 min).4 A potential advantage with CCH injections is the possibility to treat patients with bilateral disease in one stage, which is uncommon with surgery considering the nature of the procedure. In contrast, patients with contractures involving three or more fingers can be treated with surgery in one session, but would need at least two CCH injections and, in more severe cases, two or more treatment sessions.

Skin tears ranging from minor superficial skin breakage to deeper wounds occurred in more than half the patients after CCH injections in our study. Skin tears following CCH injections were reported in 11% in the multicentre randomised trial,7 and in up to 19% in other studies.13 14 Skin tears are more likely to occur in severe contractures, especially of the small finger.13 As the incidence and severity of skin tears (ie, need for wound care) may vary, we calculated the costs assuming that, on an average, one-third of the patients would require one nurse visit and also carried out a sensitivity analysis assuming an average of one nurse visit. We believe these estimates cover the costs of wound care even if the true incidence of skin tears is higher than previously reported.

We compared only direct costs, and therefore did not include the costs of lost productivity or sick leave. Among employed patients, sick leave is more likely to be necessary and longer after fasciectomy than after CCH injections. According to the Swedish Social Insurance Agency, the total cost of a 1-week sick leave based on the average salary in Sweden 2011 (including sick-pay, general payroll tax, vacation-pay and overhead costs) exceeds US$1300 (http://www.scb.se). In addition, the direct costs of CCH injections and fasciectomy may differ across countries and settings. In a Canadian study that estimated the cost (during 2005) of open carpal tunnel release, a 10 min procedure carried out under local anaesthesia, the total cost (excluding surgeon's fee) was $C137 when carried out in the main OR and $C53 when carried out in the office.15 Although the largest treatment cost for CCH injections was the cost of the injection itself, which may be substantially higher in some countries, the costs of surgery in these countries may also be higher. In a study involving 24 patients treated with fasciectomy at a single US hospital from 2008 to 2010, the average direct cost, defined as costs billed from hospital charges (facility fees) and professional charges (surgeon and anaesthesia fees) was estimated to be US$11 240.9

A limitation of our study is that only short-term outcomes were measured. The improvement was high and the minor residual contracture was similar for CCH and fasciectomy. Differences in long-term outcomes may change the cost-effectiveness of these treatments because if they differ substantially in the recurrence rate and the need for further treatments, the cost of subsequent treatments should also be considered. According to the most recent published data regarding recurrence after CCH injections (defined as contracture increase of 20° or greater in the presence of a palpable cord in joints initially corrected to a maximum of 5° contracture), the overall rate in 623 joints at 3 years was 35% (MCP 27% and PIP 56%) but the recurrence required treatment in only 7%.16 Following fasciectomy, a 3-year recurrence rate of 12% has been reported in two studies; in the first study, 4 of 33 hands had more than 30° increase in joint contracture compared with 6 weeks,11 and in the second study, 11 of 90 fingers showed progressive recurrence of PIP joint contracture but no specific definition of recurrence was stated.17 Thus, depending on the proportion of patients who subsequently need repeated treatment because of recurrent contracture in the treated fingers, it is possible that in the long term, the direct costs of treatment with CCH may exceed those of fasciectomy.

Another limitation is that in the fasciectomy group, the baseline range-of-motion measurements were carried out by different surgeons and the follow-up measurements by different therapists. The interobserver reliability of these measurements is unknown and there might be a risk that the surgeon overestimated the preoperative contracture and the treating therapist underestimated residual contracture. However, we do not believe that this issue has a substantial influence because fasciectomy was the only treatment option and the results of the post-treatment measurements, carried out by therapists, were similar in both groups.

In conclusion, treatment of DC with a single CCH injection costs 33% less, in direct costs, than fasciectomy with equivalent short-term efficacy (6 weeks) regarding reduction in contracture.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the valuable help from Ms Saskia Titman, anaesthesia nurse, and Ms Marie Davidsson, research coordinator, Department of Orthopaedics, Hässleholm Hospital.

Footnotes

Contributors: IA, ES and AL participated in study conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting of the article. EA participated in acquisition of data and critical revision of the article for important intellectual content. MW participated in analysis and interpretation of the data and critical revision of the article for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final submitted version.

Funding: This research was supported by Hässleholm Hospital and Lund University.

Competing interests: IA was a member of an Expert Group on Dupuytren’s disease for Pfizer 2012.

Ethics approval: Hässleholm Hospital Research and Development Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Desai SS, Hentz VR. The treatment of Dupuytren disease. J Hand Surg Am 2011;36:936–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Statistical Databse The National Board of Health and Welfare. 2013. http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/statistik/statistikdatabas/dagkirurgi (accessed 14 Sep 2013).

- 3.Skåne County Annual Report. Skåne County. 2010. http://www.skane.se/upload/Webbplatser/Skaneportalen-extern/OmRegionSkane/ekonomi/arsredovisning/2010/ÅR_2010_110426.pdf (accessed 14 Sep 2013).

- 4.Dias J, Bainbridge C, Leclercq C, et al. Surgical management of Dupuytren's contracture in Europe: regional analysis of a surgeon survey and patient chart review. Int J Clin Pract 2013;67:271–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crean SM, Gerber RA, Le Graverand MP, et al. The efficacy and safety of fasciectomy and fasciotomy for Dupuytren's contracture in European patients: a structured review of published studies. J Hand Surg Eur Vol 2011;36:396–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hogemann A, Wolfhard U, Kendoff D, et al. Results of total aponeurectomy for Dupuytren's contracture in 61 patients: a retrospective clinical study. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2009;129:195–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hurst LC, Badalamente MA, Hentz VR, et al. Injectable collagenase Clostridium histolyticum for Dupuytren's contracture. N Engl J Med 2009;361:968–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen NC, Shauver MJ, Chung KC. Cost-effectiveness of open partial fasciectomy, needle aponeurotomy, and collagenase injection for Dupuytren contracture. J Hand Surg Am 2011;36:1826–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herrera FA, Benhaim P, Suliman A, et al. Cost comparison of open fasciectomy versus percutaneous needle aponeurotomy for treatment of Dupuytren contracture. Ann Plast Surg 2013;70:454–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hurst L. Dupuytren's contracture. In: Wolfe SW, Hotchkiss RN, Pederson WC, Kozin SH, eds Green's operative hand surgery. 6th edn Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, 2010:153–4 [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Rijssen AL, ter Linden H, Werker PM. Five-year results of a randomized clinical trial on treatment in Dupuytren's disease: percutaneous needle fasciectomy versus limited fasciectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg 2012;129:469–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coleman S, Gilpin D, Tursi J, et al. Multiple concurrent collagenase Clostridium histolyticum injections to Dupuytren's cords: an exploratory study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2012;13:61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Skirven TM, Bachoura A, Jacoby SM, et al. The effect of a therapy protocol for increasing correction of severely contracted proximal interphalangeal joints caused by Dupuytren disease and treated with collagenase injection. J Hand Surg Am 2013;38:684–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manning CJ, Delaney R, Hayton MJ. Efficacy and tolerability of day 2 manipulation and local anaesthesia after collagenase injection in patients with Dupuytren's contracture. J Hand Surg Eur 2013. Epub ahead of print (PMID:23719171) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leblanc MR, Lalonde J, Lalonde DH. A detailed cost and efficiency analysis of performing carpal tunnel surgery in the main operating room versus the ambulatory setting in Canada. Hand (New York) 2007;2:173–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peimer CA, Blazar P, Coleman S, et al. Dupuytren contracture recurrence following treatment with collagenase Clostridium histolyticum (CORDLESS study): 3-year data. J Hand Surg Am 2013;38:12–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ullah AS, Dias JJ, Bhowal B. Does a ‘firebreak’ full-thickness skin graft prevent recurrence after surgery for Dupuytren's contracture?: a prospective, randomised trial. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2009;91:374–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.