Abstract

Objectives

It is unclear whether cultural differences or material disadvantage explain the ethnic patterning of obesogenic behaviours. The aim of this study was to examine ethnicity as a predictor of obesity-related behaviours among children in England, and to assess whether the effects of ethnicity could be explained by deprivation.

Setting

Five primary care trusts in England, 2010–2011.

Participants

Parents of white, black and South Asian children aged 4–5 and 10–11 years participating in the National Child Measurement Programme (n=2773).

Primary outcome measures

Parent-reported measures of child behaviour: low level of physical activity, excessive screen time, unhealthy dietary behaviours and obesogenic lifestyle (combination of all three obesity-related behaviours). Associations between these behaviours and ethnicity were assessed using logistic regression analyses.

Results

South Asian ethnic groups made up 22% of the sample, black ethnic groups made up 8%. Compared with white children, higher proportions of Asian and black children were overweight or obese (21–27% vs16% of white children), lived in the most deprived areas (24–47% vs 14%) and reported obesity-related behaviours (38% with obesogenic lifestyle vs 16%). After adjusting for deprivation and other sociodemographic characteristics, black and Asian children were three times more likely to have an obesogenic lifestyle than white children (OR 3.0, 95% CI 2.1 to 4.2 for Asian children; OR 3.4, 95% CI 2.7 to 4.3 for black children).

Conclusions

Children from Asian and black ethnic groups are more likely to have obesogenic lifestyles than their white peers. These differences are not explained by deprivation. Culturally specific lifestyle interventions may be required to reduce obesity-related health inequalities.

Keywords: Preventive Medicine, Social Medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Although non-white ethnicity is an established predictor of obesity-related behaviours among children in the UK, ours is one of few studies that have examined whether this effect is explained by deprivation.

Limitations of this study include a low response rate and use of self-reported measures of lifestyle behaviour which may introduce bias.

Small numbers of parents from some ethnic minority groups led to their exclusion from the analyses; our findings are only applicable to black and South Asian ethnic groups in the UK.

Introduction

Childhood obesity is associated with a number of adverse health outcomes1 2 and reducing its prevalence is a major public health priority in the UK.3 4 The distribution of overweight and obesity in this population is known to vary considerably by ethnic group.5 In 2010, the prevalence of obesity among 10–11-year-olds in England was 20–29% among Bangladeshi, Pakistani and black ethnic groups compared with 16–19% in white British children; among 4–5-year-olds these figures were 11–18% and 9–11%, respectively.6 Similarly, there are notable ethnic differences in lifestyle risk factors for obesity7; children from ethnic minority groups in the UK engage in lower levels of physical activity than their white peers,8 while South Asian children report higher consumption of dietary fat and children from black ethnic groups are more likely to skip breakfast.9 One possible explanation for the ethnic patterning of obesity-related behaviours is the effect of cultural values and norms10–13; it has been proposed that, in order to reduce health inequalities, culturally specific efforts are required to address the issue of healthy lifestyle among high-risk ethnic groups.11 14

However, children from ethnic minority groups are also over-represented in deprived areas15 and deprivation is associated with obesogenic lifestyles and environments.16–18 Therefore, it is unclear whether the ethnic patterning of obesity-related behaviours can be explained by the effects of material disadvantage, or whether cultural differences also have an impact. Analyses of national19 and regional20 UK data showed that, after adjusting for socioeconomic status, South Asian and black children were more likely to be obese than white children, but few studies have assessed the relationship with lifestyle behaviours, which may provide an insight into the underlying drivers of obesity in these groups.21

If ethnicity was identified as a risk factor for obesity-related behaviours independent of deprivation, this would provide justification for focusing on culturally specific behavioural interventions to reduce health inequalities. In contrast, evidence that the effect of ethnicity can be explained wholly by deprivation may suggest that interventions should principally address material inequalities and the built environment. The aim of this study was to describe the relationships between ethnicity and obesity-related lifestyle behaviours among school-aged children in England, and to assess whether the effects of ethnicity on lifestyle could be explained by deprivation.

Methods

We analysed cross-sectional data from the baseline survey of a cohort study.22 The cohort comprised parents of children participating in the National Child Measurement Programme (NCMP) in five Primary Care Trusts (PCTs, administrative bodies which were responsible for commissioning primary care and public health services; from April 2013, PCTs ceased to exist and responsibility for the NCMP passed to local authorities) in England between February and July 2011. The NCMP is a UK government initiative which aims to measure the heights and weights of all children in reception (ages 4–5 years) and year 6 (ages 10–11) at state primary schools in England, and provides parents with written feedback about their child's weight status. Parents of all children in reception and year 6 from Islington, Redbridge and West Essex PCTs, parents of reception year children from Sandwell PCT and parents of year 6 children from Bath and North East Somerset (BANES) PCT were invited to participate in the study (n=18 000). PCTs were selected to include a wide range of socioeconomic and ethnic groups; eligible PCTs were those willing to participate in the study and planning to conduct their NCMP measurement during the study period. Self-administered questionnaires were distributed to parents through schools on the day of the NCMP measurement, which included questions on sociodemographic characteristics, perceptions of child weight and health and lifestyle behaviours. The study protocol was approved by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine ethics committee.

The outcomes of interest were the following obesity-related lifestyle behaviours of children: low level of physical activity, excessive screen-time and unhealthy dietary behaviours, based on parents’ questionnaire responses. Children who did not meet the national physical activity recommendation of at least 1 h/day23 24 were categorised as having low level of physical activity. Children's screen time was described as the reported number of hours spent watching television or playing video games; responses were categorised according to whether or not the children exceeded international recommendations of up to 2 h/day.25 Parents also reported whether or not their child had a television in their bedroom.26 Children's diet was assessed according to the reported frequency of consumption of fruits, vegetables, sugary drinks, sweet snacks and savoury snacks (categories ranged from less than once a week to ≥3 times a day).27 Each food type was assigned a score ranging from 1 to 7, with a higher score indicating more frequent consumption of fruits and vegetables and lower consumption of sugary drinks and snacks. A healthy eating score was derived as a mean of these subscores, with a score of less than 5 indicating unhealthy dietary behaviours; a score of 5 was equivalent to a child having 3–4 portions of fruits and vegetables a day (∼70% of the Department of Health's recommended intake of fruits and vegetables28). An ‘obesogenic lifestyle’ variable was created, indicating children with all three lifestyle risk behaviours.

Children's ethnicity was recorded during the NCMP measurement, and categorised according to six UK Census ethnic groups: white, Asian or Asian British (refers to South Asian ethnic groups), black or black British, Mixed, Chinese or any other ethnic group. Children of white, Asian and black ethnicity were included in this study, as these ethnic groups were large enough to allow disaggregated analysis.

Deprivation was assessed using the English Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) 2007.29 The IMD score combines a number of indicators covering a range of social, economic, crime and housing characteristics into a single score for each lower output area in England (covering 400–1200 households). Respondents’ IMD scores (based on their postal code) were assigned to national IMD quintiles, derived from the ranking of IMD scores for the whole of England; this categorisation allowed comparison of the levels of deprivation in the sample, relative to the wider population.

Child weight status was defined using body mass index (BMI) percentiles of the UK 1990 growth curves30; cut-offs at the 2nd, 91st and 98th BMI centiles defined underweight, healthy weight, overweight, and obese, respectively.

The proportions of children who participated in low levels of physical activity, excessive screen-time behaviour and had unhealthy dietary behaviours were assessed by ethnic group and deprivation quintile. The associations of ethnicity with individual behaviours and the lifestyle variable were explored using χ2 tests for differences in proportions and logistic regression models. The final models for each outcome were adjusted for deprivation, child's sex and school year, and used analysis of complete data. All analyses were conducted using Stata V.12 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

Of the 3397 respondents to the baseline questionnaire (response rate 18.9%), 2773 had children of white, Asian or black ethnicity with complete data on ethnicity and deprivation, and formed the sample for this analysis; 8% of respondents had missing data on ethnicity and 5% had missing data on deprivation. The majority (70%) of the children in the sample were from white ethnic groups, 22% Asian ethnicity and 8% black ethnic groups. The response rate among black ethnic groups was 11.1% compared with 13.2% among Asian groups and 16% among white groups. The characteristics of the participants are shown in table 1. More children from Asian and black ethnicities were overweight and obese compared with children from white ethnic groups (p<0.001). A smaller proportion (14.3%) of white children lived in the most deprived areas, compared with Asian (23.6%) and black (46.5%) children.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and weight characteristics of white, Asian and black children participating in the 2010–2011 National Child Measurement Programme in five Primary Care Trusts in England

| Total (n=2 737), % | White (n=1 904), % | Asian (n=607), % | Black (n=226), % | p Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||

| Girls | 51.0 | 51.1 | 50.1 | 52.7 | 0.797 |

| Boys | 49.0 | 48.9 | 49.9 | 47.4 | |

| School year† | |||||

| Reception | 54.2 | 51.2 | 61.6 | 60.2 | <0.001 |

| Year 6 | 45.8 | 48.8 | 39.8 | 39.8 | |

| Deprivation quintile‡ | |||||

| 1 (most deprived) | 19.0 | 14.3 | 23.6 | 46.5 | <0.001 |

| 2 | 24.9 | 21.7 | 32.9 | 30.4 | |

| 3 | 21.3 | 19.2 | 29.8 | 16.6 | |

| 4 | 16.9 | 20.1 | 11.9 | 3.7 | |

| 5 (least deprived) | 17.9 | 24.7 | 1.7 | 2.8 | |

| Child's weight status | |||||

| Underweight | 1.8 | 1.3 | 3.8 | 0.4 | <0.001 |

| Healthy weight | 80.3 | 82.9 | 74.8 | 73.0 | |

| Overweight | 10.6 | 9.6 | 12.2 | 14.6 | |

| Obese | 7.4 | 6.3 | 9.2 | 12.0 | |

*From χ2 test for differences by ethnicity.

†Reception year=ages 4/5 years, year 6=ages 10/11 years.

‡From Index for Multiple Deprivation (IMD) score based on postcode.

Over half of all children in the sample were categorised as having unhealthy dietary behaviours (table 2), 64% had low levels of physical activity and 49% participated in excessive screen-time behaviour. Higher proportions of parents of children from Asian and black ethnic groups reported these obesity-related behaviours compared with parents of white ethnicity, with the exception of sugar-sweetened beverage consumption for which there were no differences by ethnic group. More than 40% of children of black ethnicity had a television in their room, compared with 30% white children and 11% Asian children (p<0.001).

Table 2.

Obesity-related lifestyle behaviours of white, Asian and black children enrolled in the 2010–2011 National Child Measurement Programme in five Primary Care Trusts in England

| White (n=1 904), % | Asian (n=607), % | Black (n=226), % | p Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low physical activity | ||||

| Child does not achieve ≥1 h of physical activity/day | 56.2 | 83.3 | 79.5 | <0.001 |

| High screen-time exposure | ||||

| Child engages in >2 h of screen-time/day | 42.7 | 59.4 | 68.5 | <0.001 |

| TV in child's room | 30.0 | 11.1 | 40.2 | <0.001 |

| Poor dietary behaviour | ||||

| Child has unhealthy dietary behaviours† | 48.8 | 66.5 | 62.6 | <0.001 |

| Fruit and vegetable consumption (≤5 portions/day) | 66.7 | 82.3 | 86.0 | <0.001 |

| Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption (>1/day) | 71.4 | 71.0 | 65.1 | 0.570 |

| Obesogenic lifestyle‡ | 15.8 | 37.9 | 37.5 | <0.001 |

*From χ2 test for differences by ethnicity.

†A healthy eating score <5. Diet score generated as mean of scores for consumption of fruits and vegetables (higher consumption=higher score) and sugary drinks and sweet and savoury snacks (higher consumption=lower score), range 1–7.

‡Does not achieve ≥1 h of physical activity/day, engages in >2 h of screen-time/day, and has unhealthy dietary behaviours.

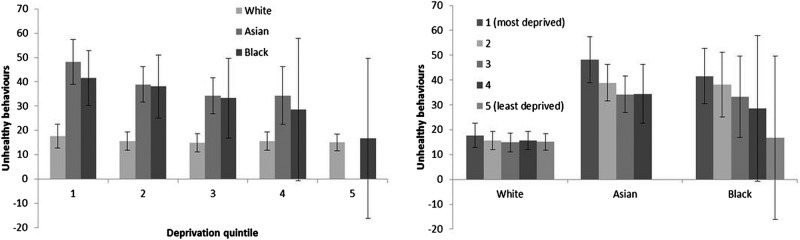

Obesogenic lifestyle was reported for twice as many children of Asian and black ethnicity as white children (37.9% Asian children, 27.5% black children and 15.8% white children). Unadjusted analyses showed that individual obesity-related behaviours (low level of physical activity, excessive TV viewing, unhealthy dietary behaviours) and obesogenic lifestyle were associated with being of black or Asian ethnicity and living in more deprived areas (table 3). In adjusted analyses, obesity-related behaviours and lifestyle remained associated with Asian and black ethnicity (table 3). In the four most deprived quintiles, obesogenic lifestyle was more common among children from Asian ethnic groups than among white children (figure 1). The same pattern was seen for black children (compared with white children) in the three most deprived quintiles. A small number of children from ethnic minority groups in the least deprived quintiles made differences in these groups difficult to detect. Children of Asian and black ethnicity had higher odds of all obesity-related behaviours than white children, and were three times more likely to have an obesogenic lifestyle (OR 3.0; 95% CI 2.1 to 4.21 for Asian children, OR 3.4; 95% CI 2.7 to 4.3 for black children).

Table 3.

Associations between respondent characteristics and obesity-related lifestyle behaviours among children participating in the 2010–2011 National Child Measurement Programme in five Primary Care Trusts in England—results from unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression analyses

| Characteristic | Physical activity |

Screen-time exposure |

Dietary behaviours |

Obesogenic lifestyle* |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

Adjusted† OR (95% CI) |

Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

Adjusted† OR (95% CI) |

Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

Adjusted† OR (95% CI) |

Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

Adjusted† OR (95% CI) |

|

| Ethnicity | ||||||||

| White (ref) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Asian | 3.0 (2.1 to 4.3) | 2.6 (1.8 to 3.7) | 2.9 (2.1 to 4.0) | 2.6 (1.9 to 3.6) | 1.8 (1.3 to 2.4) | 1.7 (1.2 to 2.4) | 3.2 (2.3 to 4.4) | 3.0 (2.1 to 4.2) |

| Black | 3.9 (3.1 to 4.9) | 3.6 (2.8 to 4.6) | 2.0 (1.6 to 2.4) | 2.0 (1.6 to 2.5) | 2.1 (1.7 to 2.7) | 2.2 (1.8 to 2.7) | 3.3 (2.6 to 4.0) | 3.4 (2.7 to 4.3) |

| Deprivation quintile‡ | ||||||||

| 5 (ref. least deprived) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 4 | 1.5 (1.2 to 2.0) | 1.3 (1.0 to 1.7) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.3) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.3) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.3) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.3) | 0.8 (0.6 to 1.1) | 1.2 (0.8 to 1.7) |

| 3 | 2.0 (1.5 to 2.5) | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.9) | 1.3 (1.0 to 1.7) | 1.2 (0.9 to 1.5) | 1.2 (0.9 to 1.5) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.3) | 1.3 (0.9 to 1.7) | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.6) |

| 2 | 2.1 (1.7 to 2.7) | 1.5 (1.1 to 1.9) | 1.5 (1.2 to 1.9) | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.8) | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.6) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.5) | 1.4 (1.0 to 1.9) | 1.3 (0.9 to 1.9) |

| 1 (most deprived) | 2.3 (1.8 to 3.1) | 1.5 (1.1 to 2.0) | 2.1 (1.6 to 2.7) | 1.9 (1.4 to 2.5) | 1.7 (1.3 to 2.2) | 1.5 (1.1 to 2.0) | 2.0 (1.5 to 2.7) | 1.8 (1.2 to 2.5) |

| School year reception (ref) | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Year 6 | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.0) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.2) | 1.7 (1.4 to 2.0) | 2.3 (1.9 to 2.7) | 1.4 (1.2 to 1.7) | 1.7 (1.4 to 2.0) | 1.5 (1.2 to 1.8) | 2.0 (1.6 to 2.4) |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Girls (ref) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Boys | 0.8 (0.7 to 0.9) | 0.8 (0.7 to 1.0) | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.5) | 1.4 (1.2 to 1.6) | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.5) | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.5) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.3) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.3) |

*Does not achieve ≥1 h of physical activity/day, engages in >2 h of screen-time/day, and has unhealthy dietary behaviours.

†Adjusted for all other characteristics (ethnicity, deprivation, school year and sex).

‡Based on Index for Multiple Deprivation (IMD) score from postcode.

Figure 1.

Percentage of children with obesogenic lifestyle (low levels of physical activity, excessive screen-time behaviour and unhealthy dietary behaviours) by ethnic group and deprivation quintile.

Discussion

In this study, we show that the prevalence of obesity and unhealthy lifestyle behaviours among school-aged children in England vary by ethnicity. Lifestyle behaviours associated with obesity were more prevalent among children from Asian and black ethnic groups than children from white ethnicity, an effect which remained after adjustment for deprivation and other respondent characteristics.

The low response rate in this study raises the possibility of non-response bias; comparison of the study sample with all children participating in the NCMP in the five PCTs showed that ethnic minority families and those living in the most deprived areas were slightly underrepresented in the sample. However, compared with the national sample of all children that took part in the NCMP in 2010/2011, the study sample had a higher proportion of Asian children (19% compared with 9% nationally) and black children (7% compared with 5% nationally), reflecting the inclusion of ethnically diverse PCTs in London and the West Midlands. Despite this, there were very small numbers of parents from some ethnic minority groups, for example, Chinese ethnic groups, which led to their exclusion from these analyses. Our findings are, therefore, only relevant to the largest ethnic minority groups in the UK. The numbers of children from Asian and black ethnic groups were not large enough to allow further disaggregation; the broad categories used in this study therefore include several heterogeneous groups which have different sociodemographic, health and behavioural profiles.12 Larger studies of ethnic minority groups are needed to understand how behaviours vary between specific ethnic minority groups and to identify which factors are important in determining these differences. The study is also limited by the use of self-reported measures of lifestyle behaviour, some of which have not been validated.31

In line with the findings from national data, we found that nearly two-thirds of children in this age group did not meet the daily recommended levels of physical activity32 and nearly three-quarters did not consume five portions of fruits and vegetables per day. Consistent with previous studies, obesity-related lifestyle behaviours were more prevalent in children of non-white ethnicity than in white children,33–35 and among children from deprived areas.36 37

Although non-white ethnicity is an established predictor of obesity-related behaviours in the UK, few studies have examined whether this effect is explained by deprivation.20 Our study found lifestyle to be associated with ethnicity after adjustment for other predictors, including deprivation, age and sex, suggesting that the effects of ethnicity on behaviours in this sample could not be explained by deprivation. Our analyses showed that at every level of deprivation, obesity-related behaviours were more prevalent in children from ethnic minority groups. These findings suggest that interventions that solely focus on material or environmental disadvantage are unlikely to be sufficient in addressing the ethnic inequalities in obesity risk. The effects of ethnicity may be explained in part by cultural beliefs and behavioural norms10; there may be a need for culturally appropriate health promotion interventions that are targeted at high-risk ethnic minority groups, with particular emphasis on those living in deprived areas. A number of potential barriers and levers to healthy lifestyles among ethnic minority families in the UK have been identified, including the importance of traditional or religious food practices and the impact of family dynamics and gender roles.11 Further work is needed to explore how the different components of ethnicity and deprivation contribute to the formation of health behaviours, and to use these to develop appropriate interventions.

School-aged children of Asian and black ethnicity in England are more likely to have lifestyles that are associated with increased risk of obesity than their white peers. These differences cannot be wholly explained by the higher prevalence of deprivation in these groups. Ethnic differences in lifestyle are apparent across all levels of deprivation, indicating a need for culturally specific lifestyle behaviour interventions to reduce obesity-related health inequalities. A better understanding of the barriers to healthy lifestyle that are experienced by different ethnic groups can inform the development of appropriate interventions for high-risk ethnic minority groups in the UK.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Primary Care Trusts, schools, parents and children who participated in this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: CLF participated in developing the study and designing the data collection instruments, coordinated the data collection, developed the analysis plan, carried out the analyses, participated in drafting the manuscript and interpreting the results and approved the final manuscript. MHP participated in developing the analysis plan and interpreting the results, drafted and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript. HC participated in developing the study and designing the data collection instruments, critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final manuscript. ASK participated in developing the study and data collection instruments, critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final manuscript. SS participated in developing the study and data collection instruments, critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final manuscript. RMV conceptualised and participated in developing the study, critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final manuscript. SK conceptualised and designed the study, participated in developing the data collection instruments and analysis plan, critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This article presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) in England under its Programme Grants for Applied Research programme (RP-PG-0608-10035).

Competing interests: ASK is also Director of Public Health Strategy and Director of Research and Development at Public Health England (PHE). SS is funded by an NIHR postdoctoral fellowship.

Ethics approval: London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine ethics committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: For information about access to the dataset, researchers should contact the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Ebbeling CB, Pawlak DB, Ludwig DS. Childhood obesity: public-health crisis, common sense cure. Lancet 2002;360:473–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reilly JJ, Kelly J. Long-term impact of overweight and obesity in childhood and adolescence on morbidity and premature mortality in adulthood: systematic review. Int J Obes 2011;35:891–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Health Cross Government Obesity Unit Healthy weight, healthy lives; a cross-government strategy for England. In: Health, ed London, 2008:56 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones Nielsen JD, Laverty AA, Millett C, et al. Rising obesity-related hospital admissions among children and young people in England: national time trends study. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e65764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saxena S, Ambler G, Cole TJ, et al. Ethnic group differences in overweight and obese children and young people in England: cross sectional survey. Arch Dis Child 2004;89:30–6 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gatineau M, Mathrani S. Obesity and ethnicity. Oxford: National Obesity Observatory, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swinburn BA, Caterson I, Seidell JC, et al. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of excess weight gain and obesity. Public Health Nutr 2004;7:123–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khunti K, Stone MA, Bankart J, et al. Physical activity and sedentary behaviours of South Asian and white European children in inner city secondary schools in the UK. Fam Pract 2007;24:237–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leung G, Stanner S. Diets of minority ethnic groups in the UK: influence on chronic disease risk and implications for prevention. Nutr Bull 2011;36:161–98 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lucas A, Murray E, Kinra S. Heath beliefs of UK South Asians related to lifestyle diseases: a review of qualitative literature. J Obes 2013;2013:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rawlins E, Baker G, Maynard M, et al. Perceptions of healthy eating and physical activity in an ethnically diverse sample of young children and their parents: the DEAL prevention of obesity study. J Hum Nutr Diet 2013;26:132–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith NR, Kelly YJ, Nazroo JY. The effects of acculturation on obesity rates in ethnic minorities in England: evidence from the Health Survey for England. Eur J Public Health 2012;22:508–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma S, Cade J, Landman J, et al. Assessing the diet of the British African-Caribbean population: frequency of consumption of foods and food portion sizes. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2002;53:439–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu J, Davidson E, Bhopal R, et al. Adapting health promotion interventions to meet the needs of ethnic minority groups: mixed-methods evidence synthesis. Health Technol Assess 2012;16:1–469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Health Survey for England. 2009. Volume 1 health and lifestyles. NHS Information Centre (16 December 2010)

- 16.Cummins S, Smith DM, Taylor M, et al. Variations in fresh fruit and vegetable quality by store type, urban–rural setting and neighbourhood deprivation in Scotland. Public Health Nutr 2009;12:2044–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dahmann N, Wolch J, Joassart-Marcelli P, et al. The active city? Disparities in provision of urban public recreation resources. Health Place 2010;16:431–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Molaodi O, Leyland A, Ellaway A, et al. Neighbourhood food and physical activity environments in England, UK: does ethnic density matter? Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activ 2012;9:75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Connelly R. Drivers of unhealthy weight in childhood: analysis of the Millennium Cohort Study. Edinburgh: Scottish Government Social Research, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cronberg A, Wild HM, Fitzpatrick J, et al. Causes of childhood obesity in London: diversity or poverty? London: London Health Observatory, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 21.El-Sayed AM, Scarborough P, Galea S. Ethnic inequalities in obesity among children and adults in the UK: a systematic review of the literature. Obes Rev 2011;12:e516–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Falconer C, Park MH, Skow A, et al. Scoping the impact of the national child measurement programme feedback on the child obesity pathway: study protocol. BMC Public Health 2012;12:783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chief Medical Officer At least five a week; Evidence on the impact of physical activity and its relationship to health. : Department of Health PA, Health Improvement and Prevention, ed. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bull FC, Expert Working Groups Physical Activity Guidelines in the U.K.: review and recommendations (technical report). School of Sport, Exercise and Health Sciences, Loughborough University May 2010

- 25.The Sedentary Behaviour and Obesity Expert Working Group Sedentary behaviour and obesity: review of the current scientific evidence. Department of Health and Department for Children, Schools and Families, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adachi-Mejia AM, Longacre MR, Gibson JJ, et al. Children with a TV in their bedroom at higher risk for being overweight. Int J Obes 2006;31:644–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adams J, White M. Are the stages of change socioeconomically distributed? A scoping review. Am J Health Promot 2007;21: 237–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Department of Health. 2013. 5 A DAY.

- 29.Department for Communities and Local Government The English indices of deprivation. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cole TJ, Freeman JV, Preece MA. Body mass index reference curves for the UK, 1990. Arch Dis Child 1995;73:25–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kohl Iii HW, Fulton JE, Caspersen CJ. Assessment of physical activity among children and adolescents: a review and synthesis. Prev Med 2000;31:S54–76 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Health and Social Care Information Centre Lifestyles Statistics Statistics on obesity, physical activity and diet, England 2013

- 33.Drenowatz C, Eisenmann J, Pfeiffer K, et al. Influence of socio-economic status on habitual physical activity and sedentary behavior in 8- to 11-year old children. BMC Public Health 2010;10:214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Rossem L, Vogel I, Moll HA, et al. An observational study on socio-economic and ethnic differences in indicators of sedentary behavior and physical activity in preschool children. Prev Med 2012;54:55–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lowry R, Kann L, Collins JL, et al. The effect of socioeconomic status on chronic disease risk behaviors among US adolescents. J Am Med Assoc 1996;276:792–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoyos Cillero I, Jago R. Systematic review of correlates of screen-viewing among young children. Prev Med 2010;51:3–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hanson M, Chen E. Socioeconomic status and health behaviors in adolescence: a review of the literature. J Behav Med 2007;30:263–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.