Abstract

Aims

To compare quality of life (QoL) and factors associated with QoL change after retropubic (RMUS) and transobturator (TMUS) midurethral slings using the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire, (IIQ) and the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire (ICIQ).

Methods

Five hundred ninety seven women in a multicenter randomized trial of RMUS vs. TMUS were examined. The IIQ and ICIQ were obtained at baseline, 12 and 24 months. Repeated measures analysis of variance tested for differences by treatment group over time. Multivariable analysis identified factors associated with QoL change at 12 months post- operative, controlling for treatment group and baseline QoL.

Results

Improvement in IIQ was associated with: treatment success, younger age, improvement in stress incontinence (SUI) symptom severity and bother (all p < 0.05). Improvement in ICIQ was associated with treatment success, younger age, improvement in SUI symptom severity and bother, lower body mass index and no re-operation (all p < 0.05). Improvement of the IIQ was stable over time (p =0.35) for both treatment groups (p=0.66) whereas the ICIQ showed a small but clinically insignificant decline (p=0.03) in both treatment groups (p=0.51).

Conclusions

Postoperative QOL was improved after RMUS and TMUS. Measures of QOL functioned similarly, although more surgically modifiable urinary incontinence factors predicted improvement with the IIQ.

Keywords: Urinary incontinence, Quality of life, Midurethral sling

Introduction

Urinary incontinence (UI) is a global problem with a significant negative impact on quality of life1. Although prevalence rates vary depending on definition of UI and subject age, a recent systematic review of population based studies reported rates from 16.2 to 69.2%1. Quality of life (QoL) assessment is increasingly important in patient care and as an outcome in treatment trials. A variety of condition specific QoL instruments are available for use for UI without consensus of superiority.

Other investigators reported that age, severity and type of UI, number of UI episodes, body weight, stress, and help-seeking behavior were significantly associated with lower QoL in women with stress urinary incontinence (SUI) seeking surgical intervention2. We previously analyzed baseline data from the cohort of 597 women enrolled in the trial of midurethral slings (TOMUS) and found that lower QoL was associated with non-UI factors such as younger age and higher body mass index (BMI) as well as type and severity of UI symptoms3. The objective of this paper was to assess the improvement in UI-related QoL in women after retropubic midurethral sling (RMUS) and transobturator midurethral sling (TMUS) for stress urinary incontinence (SUI) using two measures, the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire (IIQ) 4 and the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire (ICIQ) 5. A secondary objective was to compare the two instruments by identifying those clinical and demographic factors associated with change in each measure.

Materials and Methods

Participants

We analyzed data from a randomized trial of women undergoing SUI surgery conducted by the Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network (UITN). The TOMUS (N=597) compared RMUS versus TMUS for SUI6. The methodology and outcomes of this trial are published. 6 Eligibility criteria included a combination of self-reported symptoms and clinical examination measures. Self-reported SUI symptoms included: duration of SUI symptoms more than 3 months, and a Medical, Epidemiologic and Social Aspects of Aging questionnaire (MESA) 7 SUI symptom index greater than MESA urge incontinence symptom index. Eligibility required a positive provocative stress test at a standardized bladder volume of 300ml. The trial allowed concomitant vaginal surgeries. All participants provided written informed consent and each local institutional review board reviewed and approved the study protocols.

Measures

The outcome of interest was change in QoL after surgery. We used two condition-specific measures of QoL: the ICIQ and IIQ. 4,5,8 The ICIQ assessed the impact of UI on everyday life; whereas, the IIQ assessed the impact of UI on various activities, roles, and emotional states.

Potential predictors of QoL included treatment success demographic and clinical characteristics, and a range of patient reported assessments of UI symptom severity, improvement after surgery, and postoperative pain that were considered potential predictors of change in QoL after surgery (Table 1)9–11 Treatment success was measured by a composite that included both subjective and objective measures of UI: the absence of stress type symptoms on the MESA questionnaire, 9 no leakage on the 3-day voiding diary, a negative provocative stress test, a negative 24-hour pad test, and no retreatment (behavioral, pharmacological or surgical) for SUI. 6 Definitions of clinical terms and methods of evaluation of participants were uniform across all sites and adhered to standards set by the International Continence Society.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Participants (n=527)

| Variables | Transobturator MUS N=263 |

Retropubic MUS N=264 |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years: mean (sd), yrs | 53.8 (11.3) | 53.4 (10.2) |

| Race /Ethnicity :n (%) | ||

| Hispanic | 32 (12%) | 29 (11%) |

| Non-hispanic White | 208 (79%) | 216 (82%) |

| Non-hispanic Black | 8 (3%) | 6 (2%) |

| Non-hispanic Other | 15 (6%) | 13 (5%) |

| Occupational Class: mean (sd) | 59.8 (22.8) | 59.8 (22.9) |

| Baseline BMI: mean (sd) | 29.9 (6.3) | 30.4(6.8) |

| Prior UI Treatment or surgery: n (%) | 149 (57%) | 153 (58%) |

| Baseline Anal incontinence: n (%) | 155 (59%) | 155 (59%) |

| Baseline Smoking status: n (%) | ||

| Never | 145 (55%) | 146 (55%) |

| Former | 89 (34%) | 83 (31%) |

| Current | 29 (11%) | 35 (13%) |

| UI type and Severity | ||

| Stress UI index (MESA) at baseline: mean (sd) | 72.5 (17.2) | 71.1 (17.2) |

| Stress UI index (MESA) at 12 months: mean (sd) | 8.8 (16.6) | 8.0 (16.4) |

| Urge UI index (MESA) at baseline: mean (sd) | 37.3(21.6) | 33.1 (21.9) |

| Urge UI index (MESA) at 12 months: mean (sd) | 9.9 (14.1) | 10.2 (14.8) |

| Baseline UI Severity (PGI-S): n (%) | ||

| Normal or Mild | 50 (19%) | 58 (22%) |

| Moderate | 123 (47%) | 142 (54%) |

| Severe | 89 (34%) | 63 (24%) |

| Symptom bother (UDI) : mean (sd) | ||

| Baseline | 136.3 (41.6) | 131.1 (453.8) |

| 12 months | 26.0 (39.0) | 24.4 (34.3) |

| Sexual Activity at 12 months | ||

| Sexually active: n (%) | 171 (65%) | 176 (67%) |

| Sexual Function(PISQ-12): mean (sd) | 38.0 (6.1) | 37.3 (5.6) |

| Surgical and Post-operative Course Experienced any adverse events: n (%) | ||

| No AE or SAE | 200 (76%) | 177 (67%) |

| Any AE, no SAE | 47 (18%) | 57 (22%) |

| Any SAE w/ or w/o AE | 16 (6%) | 30 (11%) |

| Any intraoperative AE: n (%) | 11 (4%) | 19 (7%) |

| Reoperation for UI in 12 months: n (%) | 52 (20%) | 49 (19%) |

| Post-operative voiding dysfunction*n (%) | ||

| Normal | 257 (98%) | 251 (95%) |

| Catheter use | 0 (0%) | 7 (3%) |

| Surgical intervention | 3 (1%) | 5 (2%) |

| All other voiding dysfunction | 1 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) |

| Post-operative pain**n (%) | 5 (2%) | 5 (2%) |

Voiding dysfunction is defined as a complication if one of the following criteria are met: 1) uses a catheter to facilitate bladder emptying at or beyond the 6 week visit or 2) has undergone medical therapy to facilitate bladder emptying at or beyond the 6 week visit or 3) has undergone surgical therapy to facilitate bladder emptying at anytime after TOMUS surgery.

Pain is defined as a complication if the following criteria are met at or beyond the 6 week visit: 1) patient answers “yes” to the introductory stem question “Have you had any pain within the last 24 hours as a result of your incontinence operation?” and 2) patient answers any of the first three McCarthy pain questions at a level 75mm or greater on the visual analog scale and 3) patient answers the bother question on the McCarthy visual analog scale at a level 75mm or greater.

Data Analysis

Continuous variables are reported with mean (SD) and range, whereas categorical variables are presented with frequency and percent.

We first evaluated the change over time in QoL (IIQ and ICIQ), using repeated measures analysis of variance controlling for time (6, 12 and 24 months), treatment group, interaction of time and treatment, as well as the baseline value.

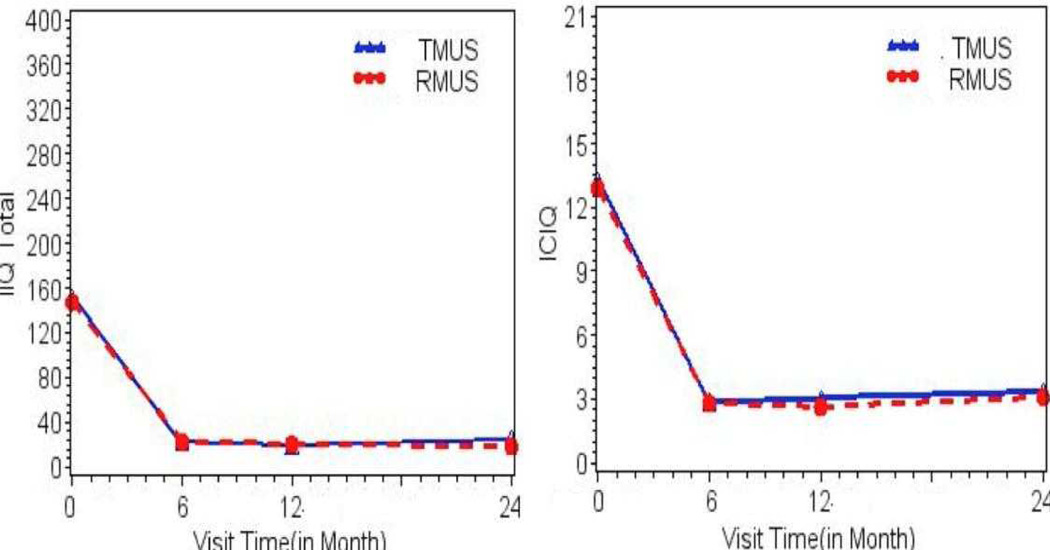

This analysis showed that there was minimal change in QoL scores between 12–24 months (Figure 1). Therefore, to maximize the cases with available data, we analyzed change in QoL between baseline and 12 months. Based on data in Figure 1, we assume that the results at 24 months would be similar. To determine the association of clinical and demographic factors with UI related QoL, we computed a bivariate regression analysis of each potential predictor on change in IIQ or ICIQ. We then computed a multiple regression analysis that included all variables associated bivariately with change in IIQ or ICIQ at p<0.20. In the final models, we removed variables that were no longer statistically significant at p=0.05. Treatment group and baseline values of the variables were included in all models.

FIGURE 1.

Mean IIQ and ICIQ by study visit and treatment group

Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc. Cary, NC). A 5% two-sided significance level was used for all statistical testing.

Results

Figure1 displays mean IIQ and ICIQ values at each study visit by treatment group. The change from baseline to follow-up was substantial in both groups but the change over time post-surgery was minimal though statistically significant for ICIQ (p=0.03) but not for IIQ (p=0.35). The difference between the treatment groups was not statistically significant for either IIQ (p=0.66) or ICIQ (p=0.51). The analytical sample consisted of 527 participants, excluding 70 women who had not completed the 12-month survey. To check for response bias, we compared those who completed the survey (n=527) to those who did not (n=70) on selected characteristics (not shown). Responders were similar to non-responders on all characteristics except that responders were slightly older (53.6 vs. 47.3 years, p<0.0001). Importantly, they were similar with regard to baseline UI severity and QoL.

Sample Characteristics

The 527 women in this analysis were predominantly white (80%) and middle-aged (mean [SD], 53.6 [10.8.0] years) yet socioeconomically diverse. By trial design, they all had stress UI (mean [SD] MESA stress index, 71.8 [17.2]), but many also reported some urge UI (mean [SD] MESA urge index 35.2 [21.8]). More than half (58%) reported prior treatment for UI and concomitant anal incontinence (59%). Mean body mass index BMI was 30.1 (6.6) kg/m2. Women randomized to the two MUS approaches did not differ on the characteristics at baseline or at 12 months after surgery (Table 1).

Changes in Quality Of life

The mean (SD) change from baseline to 12 months in the IIQ was a decrease of 129 points (96.1) points (p<0.0001). Similarly the mean (SD) change in the ICIQ was a decrease of 10.3 (5.0) points (p=0.001). Four hundred fifty nine women (90%) reported that they were “much better” or “very much better” on the Patient Global Impression of Improvement scale at 12 months.

Results of the multivariable analyses are displayed in Table 2. Quality of Life improvement measured by change in IIQ was associated with treatment success, younger age , improvement in SUI symptom severity and improvement in symptom bother , explaining 84% of the variability in QoL. Quality of Life improvement measured by change in ICIQ was similarly associated with treatment success (p < 0.001), younger age (p = 0.001), improvement in SUI symptom severity (p < 0.001), improvement in symptom bother (p < 0.001), lower baseline BMI (p= 0.02) and no reoperation for SUI in 12 months (p = 0.009), explaining 76% of the variability in change in QoL.

Table 2.

Predictors of Change in Quality of Life at 12 Months

| Variables | estimate | p-value | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| IIQ | |||

| Model p-value | . | <0.001 | 0.84 |

| Treatment Group | . | 0.68 | |

| Transobturator MUS | 129.81 | ||

| RetropublicMUS | 128.39 | ||

| Baseline IIQ | 0.79 | <0.001 | |

| Overall Treatment Success | . | 0.007 | |

| No | 124.05 | ||

| Yes | 134.14 | ||

| Age | −0.50 | 0.002 | |

| Stress UI index change | 0.61 | <0.001 | |

| Symptom Bother (UDI) change | 0.25 | <0.001 | |

|

ICIQ | |||

| Model p-value | . | <0.001 | 0.76 |

| Treatment Group | . | 0.16 | |

| Transobturator MUS | 9.74 | ||

| Retropubic MUS | 10.05 | ||

| Baseline ICIQ | 0.79 | <0.001 | |

| Overall Treatment Success | . | <0.001 | |

| No | 8.87 | ||

| Yes | 10.92 | ||

| Age | −0.03 | 0.001 | |

| Baseline BMI | −0.04 | 0.02 | |

| UI reoperation in 12 months | . | 0.009 | |

| No surgery | 10.34 | ||

| Any surgery | 9.45 | ||

| Stress UI index change | 0.04 | <0.001 | |

| Symptom Bother (UDI) change | 0.02 | <0.001 | |

Discussion

This study shows that condition-specific QoL improves after midurethral sling surgery, regardless of approach (RMUS or TMUS) or QoL measure. It should be reassuring to surgeons and patients alike that, after midurethral sling surgery for SUI, patients report about 80% improvement in QoL that is sustained at least 2 years. Women with the greatest QoL improvement were younger, reported more improvement in UI symptom bother and had successful surgery. These data should be integral in counseling women before midurethral sling surgery for SUI.

This analysis reinforces our understanding of the importance of patient reported outcomes for minimally invasive continence surgery. This study offered a unique opportunity to compare predictors of QOL change using the ICIQ and the IIQ. The fact that reductions in scores were similar for both measures (77% for ICIQ and 85% for IIQ at 1 yr) should be reassuring to clinicians and clinical researchers. Data from this study are consistent with prior findings that QoL after SUI surgery is observed after a variety of surgical approaches including Burch retropubic urethropexy, traditional sling operations, and midurethral slings. Most reports support roughly a 70% to 80% improvement that is sustained over time. 2,12,13 Analysis of the SISTEr trial comparing Burch vs. Sling showed a 78% improvement after both procedures, maintained up to 2 years.13

Our data are also consistent with large international trials demonstrating similar improvements in QoL after RMUS and TMUS. 2,14,15 Porena et al14 used the IIQ-7 to assess QoL changes and found no differences between the RMUS and TMUS procedures with scores decreasing from 8 to 0 at 1 year. Meschia et al 16 used the ICIQ to assess improvements in QoL also showing 80 to 85% improvements in overall scores. 18

Measuring QoL with different instruments poses some challenges, namely: Which is the better tool to assess patient oriented outcomes? The ICIQ is a brief 3-scored and 1-unscored self diagnostic item that assesses the prevalence, frequency and volume of leakage as well as the QoL impact.5 The ICIQ demonstrates good construct validity and reliability and high correlation with the Sandvik severity index. 17,18 In this study the ICIQ score improved from 13 to 3 following mid-urethral sling surgery and although there was a statistically significant “deterioration” of the ICIQ score from 2.9 to 3.4 at 24 months, this is unlikely to represent a clinically relevant finding. The observed deterioration in the ICIQ score at 24 months could be related to the older age of the responders at 12 months, as younger women reported significantly greater improvement in QoL. A similar deterioration in IIQ scores was not observed. Finally, whereas there are no published data on ICIQ minimum important differences, and since both the 12 and 24 month ICIQ scores remain below 4, it would appear that any leakage reported remains quite low.

This study used the IIQ long form, developed as a condition specific tool to assess the impact of UI on QoL4. Thirty questions measure the effect of UI on daily activities within four subscales of physical activity, travel, social/relationships, and emotional health. The subscale scores are summed for a total score from 0 to 400 with higher scores representing more negative impact on QoL. This scale exclusively measures impact on QoL, unlike the ICIQ, which includes frequency and severity of UI of nearly half of the total score. While there is no published data on the minimum important difference for the IIQ long form, we observed no difference between RMUS or TMUS with this tool and the response was durable to 2 years.

Interestingly, the models predicting change in QoL as measured by the IIQ identified younger age but also more surgically modifiable UI factors, specifically, treatment success, symptom severity, and symptom bother. In addition, these factors explained more of the variability in QoL improvement after surgery. Improvement in the ICIQ was associated not only with improvement in UI-related symptom severity and bother, but also with the unrelated non-modifiable UI factors of lower BMI and no reoperation in the first year. This finding that the IIQ is responsive to more UI-related outcomes provides support for use of the IIQ to measure QoL in surgical studies.

Predictors of improved QOL after surgery for SUI in the SISTEr study were decreased UI bother, improved severity, and younger age, as well as Hispanic ethnicity and assigned treatment (having had a Burch) 2. In this study, ethnicity and assigned treatment were not predictive of improved QOL. Although the samples for both the SISTEr and TOMUS trials were composed of approximately 11% Hispanic women, it is unclear why ethnicity was not an important predictive factor in the TOMUS population. That assigned treatment was not related to QoL improvement in this study may reflect the similar nature, success, and complication rates (i.e. urinary retention) between the two midurethral sling procedures and a lack of statistical power.

Strengths of this study include the prospective, multicenter, randomized design of the trial using two different validated, condition-specific measures of QOL. Limitations of this study include the lack of available information on the IIQ and ICIQ minimum important difference to inform clinically meaningful differences and changes over time.

In conclusion, women undergoing either RMUS or TMUS for SUI can expect similar, substantial improvements in condition-specific QOL sustained over at least two years. Whereas many factors are associated with post-operative QoL improvement as measured with both the IIQ and ICIQ, the IIQ was associated with more direct UI-related factors than was the ICIQ, and may be the preferred tool for SUI surgical studies.

Acknowledgments

Supported by cooperative agreements from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, U01 DK58225, U01 DK58229, U01 DK58234, U01 DK58231, U01 DK60379, U01 DK60380, U01 DK60393, U01 DK60395, U01 DK60397, and U01 DK60401.

References

- 1.Kwon BE, Kim GY, Son YJ, et al. Quality of life of women with urinary incontinence: a systematic literature review. Int Neurourol J. 2010;14:133–138. doi: 10.5213/inj.2010.14.3.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tennstedt SL, Litman HJ, Zimmern P, et al. Quality of life after surgery for stress incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19:1631–1638. doi: 10.1007/s00192-008-0700-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sirls LT, Tennstedt S, Albo M, et al. Factors associated with quality of life in women undergoing surgery for stress urinary incontinence. J Urol. 2010;184:2411–2415. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shumaker SA, Wyman JF, Uebersax JS, et al. Continence Program in Women (CPW) Research Group: Health-related quality of life measures for women with urinary incontinence: the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire and the Urogenital Distress Inventory. Qual Life Res. 1994;3:291–306. doi: 10.1007/BF00451721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Avery K, Donovan TJ, Peters C, et al. ICIQ: A brief and robust measure for evaluating the symptoms and impact of urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2004;23:322–330. doi: 10.1002/nau.20041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richter HE, Albo ME, Zyczynski HM, et al. Retropubic versus transobturator midurethral slings for stress incontinence. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2066–2076. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herzog AR, Diokno AC, Brown MB, et al. : Two-year incidence, remission, and change patterns of urinary incontinence in noninstitutionalized older adults. J Gerontol. 1990;45:M67–M74. doi: 10.1093/geronj/45.2.m67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uebersax JS, Wyman JF, Shumaker SA, et al. Short forms to assess life quality and symptom distress for urinary incontinence in women: the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire and the Urogenital Distress Inventory. Continence Program for Women Research Group. Neurourol Urodyn. 1995;14:131–139. doi: 10.1002/nau.1930140206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nam CB, Boyd M. Occupational Status in 2000; Over a Century of Census-Based Measurement. Popul Res Policy Rev. 2004;23:327–358. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yalcin I. RC Bump: Validation of two global impression questionnaires for incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:98–101. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rogers RG, Coates KW, Kammerer-Doak D, et al. A Short form of the Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary incontinence Sexual Questionnaire (PISQ-12) Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 2003;14:164–168. doi: 10.1007/s00192-003-1063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richter HE, Norman AM, Burgio KL, Goode PS, Wright KC, Benton J, et al. Tension-free vaginal tape: a prospective subjective and objective outcome analysis. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2005;16(2):109–113. doi: 10.1007/s00192-004-1238-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holmgren C, Hellberg D, Lanner L, Nilsson S. Quality of life after tension-free vaginal tape surgery for female stress incontinence. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2006;40(2):131–137. doi: 10.1080/00365590510031309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Porena M, Costantini E, Frea B, Giannantoni A, Ranzoni S, Mearini L, et al. Tension-free vaginal tape versus transobturator tape as surgery for stress urinary incontinence: results of a multicentre randomised trial. Eur Urol. 2007;52(5):1481–1490. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.04.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murphy M, van Raalte H, Mercurio E, Haff R, Wiseman B, Lucente VR. Incontinence-related quality of life and sexual function following the tension-free vaginal tape versus the "inside-out" tension-free vaginal tape obturator. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19(4):481–487. doi: 10.1007/s00192-007-0482-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meschia M, Bertozzi R, Pifarotti P, Baccichet R, Bernasconi F, Guercio E, et al. Peri-operative morbidity and early results of a randomised trial comparing TVT and TVT-O. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18(11):1257–1261. doi: 10.1007/s00192-007-0334-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klovning A, Avery K, Sandvik H, Hunskaar S. Comparison of two questionnaires for assessing the severity of urinary incontinence: The ICIQ-UI SF versus the incontinence severity index. Neurourol Urodyn. 2009;28(5):411–415. doi: 10.1002/nau.20674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sandvik H, Seim A, Vanvik A, Hunskaar S. A severity index for epidemiological surveys of female urinary incontinence: comparison with 48-hour pad-weighing tests. Neurourol Urodyn. 2000;19(2):137–145. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6777(2000)19:2<137::aid-nau4>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]