Abstract

AIM:

The aim of our study is to compare the results of laparoscopic mesh vs. suture rectopexy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

In this retrospective study, 70 patients including both male and female of age ranging between 20 years and 65 years (mean 42.5 yrs) were subjected to laparoscopic rectopexy during the period between March 2007 and June 2012, of which 38 patients underwent laparoscopic mesh rectopexy and 32 patients laparoscopic suture rectopexy. These patients were followed up for a mean period of 12 months assessing first bowel movement, hospital stay, duration of surgery, faecal incontinence, constipation, recurrence and morbidity.

RESULTS:

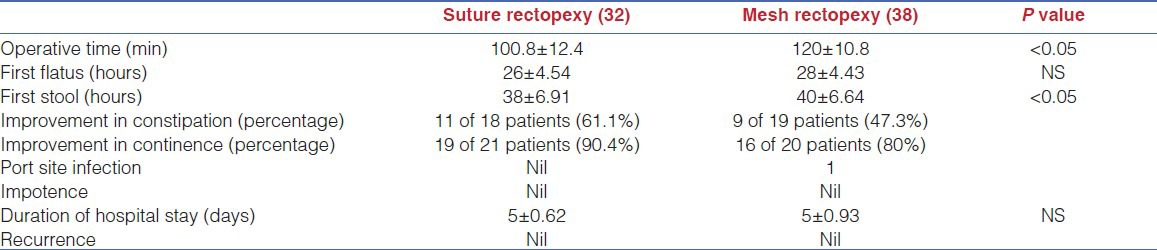

Duration of surgery was 100.8 ± 12.4 minutes in laparoscopic suture rectopexy and 120 ± 10.8 min in laparoscopic mesh rectopexy. Postoperatively, the mean time for the first bowel movement was 38 hrs and 40 hrs, respectively, for suture and mesh rectopexy. Mean hospital stay was five (range: 4-7) days. There was no significant postoperative complication except for one port site infection in mesh rectopexy group. Patients who had varying degree of incontinence preoperatively showed improvement after surgery. Eleven out of 18 (61.1%) patients who underwent laparoscopic suture rectopexy as compared to nine of 19 (47.3%) patients who underwent laparoscopic mesh rectopexy improved as regards constipation after surgery.

CONCLUSION:

There were no significant difference in both groups who underwent surgery except for patients undergoing suture rectopexy had better symptomatic improvement of continence and constipation. Also, cost of mesh used in laparoscopic mesh rectopexy is absent in lap suture rectopexy group. To conclude that laparoscopic suture rectopexy is a safe and feasible procedure and have comparable results as regards operative time, morbidity, bowel function, cost and recurrence or even slightly better results than mesh rectopexy.

Keywords: Laparoscopy, mesh rectopexy, presacral fascia, rectal prolapse, suture rectopexy

INTRODUCTION

Complete rectal prolapse is a debilitating condition, which affects both the very young and the elderly and can cause faecal incontinence.[1] Several operations have been proposed to correct rectal prolapse, which can be divided into transabdominal and perineal procedures but still the best operation for rectal prolapse remains a controversial subject.[2] Laparoscopic rectopexy has the same clinical and functional results as laparotomic rectopexy, but with a shorter postoperative hospital stay and lower costs.[3] Without the need for bowel resection, the laparoscopic rectopexy may constitute an optimal application of laparoscopic colorectal techniques and may soon become the gold standard for the treatment of rectal prolapse.[4] Suture rectopexy is equally effective as posterior mesh rectopexy in preventing recurrences and eliminates the use of foreign material, which is sometimes associated with intense fibrosis, sepsis and increased constipation.[5] Patients with complete rectal prolapse have markedly impaired rectal adaptation to distention, which may contribute to anal incontinence, and consequently more than half of the patients with rectal prolapse have coexisting incontinence.[6,7,8,9,10] Constipation is associated with prolapse in 15-65% of patients.[9] The aim of treatment is to control the prolapse, restore continence and prevent constipation or impaired evacuation.[11,12,13] The rationale for rectal fixation is to keep the rectum attached in the desired elevated position until it becomes fixed by scar tissue.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In our institution in the department of surgery, 70 patients have undergone laparoscopic rectopexy, of which 38 patients underwent mesh rectopexy and 32 patients underwent suture rectopexy. Another 14 patients who had redundant sigmoid, all underwent excision along with suture rectopexy and were excluded from the study. Before surgery, all patients had undergone either a barium enema or colonoscopy at some stage of their investigation to exclude a proximal colonic lesion. Preoperative assessment of incontinence and constipation was done in all patients by questionnaire using Cleveland Clinic Florida (Wexner) faecal incontinence score. Preoperatively, incontinence was seen in 41 (58.5%) patients out of which 21 belonged to suture rectopexy group and 20 to mesh rectopexy group and constipation in 37 (52.8%) out of which 18 belonged to suture rectopexy group and 19 to mesh rectopexy group. Preoperatively, all patients of both the groups were advised to do kegel sphincter exercises. Patients underwent good bowel preparation from 1 day before surgery and were on only plain liquids till the night before surgery. They were kept nil orally from night before surgery and were given a dose of antibiotic before surgery.

Technique

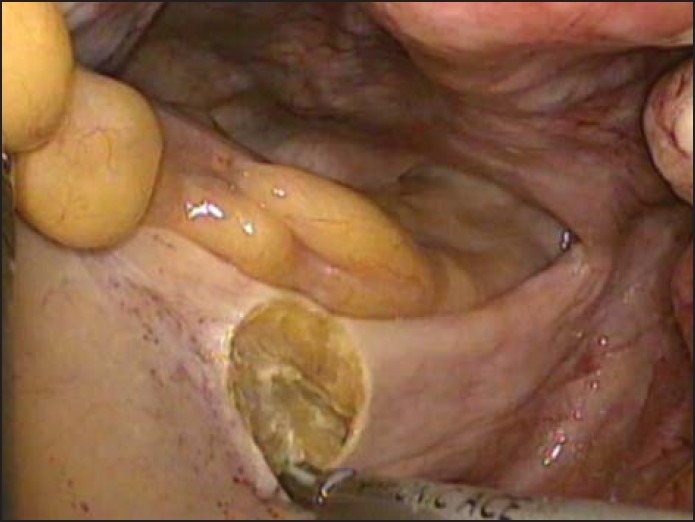

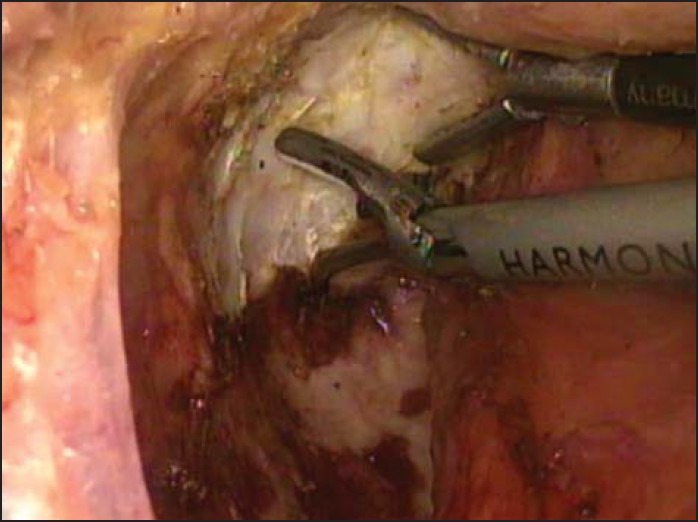

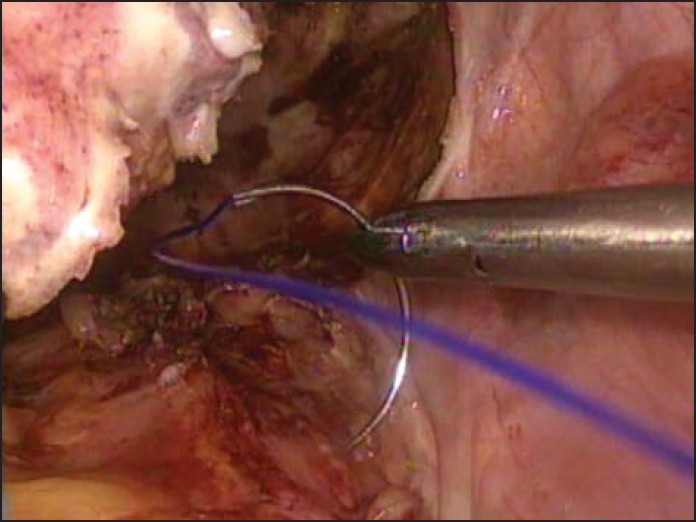

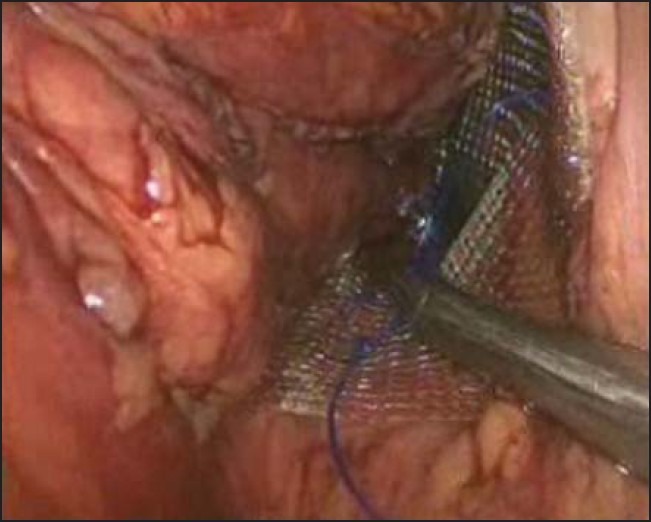

In the operation theatre under general anaesthesia, patients were catheterised and placed in Trendelenberg position. After creation of pneumoperitoneum through a four port approach, one supraumbilical telescopic port (10 mm), second right hand working port in right iliac fossa (10 mm), third left hand working port in left iliac fossa (5 mm), fourth little above the third as assistant port for retracting rectosigmoid junction (5 mm). The dissection was started by opening peritoneum on right side of rectum [Figure 1] using harmonic scalpel after identifying right ureter and safe guarding it, then dissecting rectum from presacral fascia in holy plane of safety staying close to rectum to avoid injury to autonomic nerves, especially nervi erigentes and pre sacral venous plexus. Then dissection was done on left side after identifying left ureter and also anteriorly. Dissection was carried out downwards till pelvic floor [Figure 2]. Till now the procedure is same, in case of suture rectopexy rectum is pulled up and mesorectum is sutured to presacral fascia over sacral promontory using 2-0 prolene [Figure 3], and in case of mesh rectopexy, mesh is placed behind dissected rectum [Figure 4], upper end of mesh is fixed to presacral fascia over sacral promontory using 2-0 prolene, another stay suture given over lower part of mesh, then mesh fixed on either side of rectum such it covers about 2/3rd of rectum. In both procedures closed suction drain was given in presacral region and reperitonealised with 2-0 vicryl.

Figure 1.

Opening the peritoneum on the right side to enter holy plane

Figure 2.

Dissection of rectum up to the pelvic floor

Figure 3.

Taking a bite in the presacral fascia over sacral promontory to fix the rectum

Figure 4.

Fixing of mesh posterior to rectum to presacral fascia

Postoperatively, oral liquids were started on second day and were given stool softener for two weeks. Drain was removed after 48 hrs. Postoperative course of the patients was recorded with attention paid to first bowel movement after surgery, faecal incontinence, constipation, recurrent prolapse, morbidity and mortality.

RESULTS

During the period between March 2007 and June 2012, 70 patient including both male and female of age ranging between 20 years and 65 years (mean 42.5 yrs) underwent laparoscopic rectopexy (38-mesh rectopexy, 32-suture rectopexy). There was no injury to the bowel or rectum during surgery in any case. There were no conversions. Preoperatively incontinence was seen in 41 (58.5%) patients and constipation in 37 (52.8%). Postoperatively, improvement in these symptoms is shown in the Table 1. Statistical analysis was done using Student's t-test and χ2 test. Results were expressed as mean ± SD. P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant and others not significant (NS). [Table 1] All patients were followed up for average period of 12 months (range: 1-24 months) and no recurrence was found.

Table 1.

Results comparing laparoscopic suture rectopexy & laparoscopic mesh rectopexy

DISCUSSION

Laparoscopic procedures for complete prolapse rectum have become the operations of choice because of the benefits of minimal invasive surgery along with comparative rates of recurrence.[14] A variety of open abdominal surgical procedures have been practiced for the treatment of complete prolapse of the rectum.[15,16,17,18] 14 patients had redundant sigmoid colon who underwent resection and anastomosis of recto-sigmoid. All these 14 patients underwent suture rectopexy laparoscopically and none underwent mesh rectopexy, hence these patients were excluded from the study.

Laparoscopic rectopexy involving any sort of mesh fixation increases the cost of surgery, duration of operation and the technical skills required to accomplish the operation when compared to laparoscopic suture rectopexy.

Constipation and anal incontinence are two associated problems with complete prolapse of the rectum. Patients with complete rectal prolapse have markedly impaired rectal adaptation to distension which may contribute to anal incontinence and consequently, more than half of the patients with rectal prolapse have coexisting incontinence.[6] In the US, the Cleveland Clinic Florida (Wexner) faecal incontinence score remains the most commonly used score because of its easiness. The sum of five parameters is determined that are scored on a scale from 0 (absent) to 4 (daily) frequency of incontinence to gas, liquid and solid, of need to wear pad, and of lifestyle changes. A score of 0 means perfect control, a score of 20 complete incontinence. In this study too, we used this questionnaire to know the improvement in symptoms postoperatively. Continence levels improved in 19 (90.4%) of the 21 patients after suture rectopexy and 16 of 20 (80%) in mesh rectopexy. A series of 42 patients of complete rectal prolapse undergoing suture rectopexy found that 90% patients had improvement in the continence levels postoperatively. An 80% improvement in continence after open suture rectopexy has also been reported by Graf et al.[17] In the same review, laparoscopic posterior mesh rectopexy, using both non absorbable and absorbable meshes, showed a better result in terms of improvement in continence after surgery, though it was still less than after laparoscopic suture rectopexy. The slight edge, though not significant, in improvement in continence after laparoscopic suture rectopexy when compared to laparoscopic mesh rectopexy can be explained by the fact that a mesh does interfere in rectal distensibility as compared to sutures only.[19] More objective data can be obtained from anophysiology studies, but the results have to be interpreted with caution in the context of all other factors. Duration of surgery is also taken to gauge the advantages of an operation. In our study, the mean duration of suture rectopexy was 100.8 ± 12.4 minutes and 120 ± 10.8 min for mesh rectopexy with P value of < 0.05 which is statistically significant. This compares well with the average duration of surgery for laparoscopic suture rectopexy by Heah et al.,[4] as 96 minutes (range: 50-150 minutes).[20] As regards laparoscopic mesh rectopexy average operating time of 140 minutes (range: 105-240 minutes) has been reported by Siproudhis et al.[6] The longer operating time in mesh rectopexy is understandable because of the extra time taken in introducing the mesh and then adjusting its position. Length of post operative hospital stay is an indicator of the patient's recovery and post operative complications. In our study, it was 5 ± 0.62 days (range: 4-7 days) in suture rectopexy group and 5 ± 0.93 in mesh rectopexy group with no significance between the two groups. A similar duration of stay after laparoscopic suture rectopexy has been reported by Graf et al.[21] There was no significant intraoperative or postoperative complication in our study except for one case of port site infection. In our study, constipation was observed in 37 (52.8%) of 70 patients preoperatively. In the postoperative period, 11of 18 patients of suture (61.1%) and 9 of 19 patients of mesh (47.3%) rectopexy improved as regards their constipation. Time taken for passage of first flatus in suture rectopexy group is 26 ± 4.54 when compared to 28 ± 4.43 in mesh rectopexy group with no significance between them, but time taken for first stool postoperatively was statistically significant in suture group (38 ± 6.91) when compared to mesh group (40 ± 6.64). The lateral ligaments containing the parasympathetic inflow to the left colon may be cut during mobilisation which can lead to constipation. At least two studies have demonstrated a higher incidence of constipation with significant changes in rectal sensation when lateral ligaments are divided as compared with when they are not.[22,23] One of the important parameters to gauge the success of rectal prolapse surgery is the incidence of recurrence. Recurrence after suture rectopexy has been reported as ranging from 0% to 3%.[17] Recurrence rates with posterior mesh rectopexy range from 0% to 6%.[18] The laparoscopic techniques have not made any significant difference on the recurrence rates which continue to range from 0% to 10% in a follow up of 8-30 months.[18]

CONCLUSION

To conclude that laparoscopic suture rectopexy is a safe and feasible procedure and has comparable results as regards operative time, morbidity, bowel function, cost and recurrence or even slightly better results, when compared to the data available on laparoscopic mesh and resection rectopexy.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bachoo P, Brazzelli M, Grant A. Surgery for completerectal prolapse in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000:CD001758. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiu HH, Chen JB, Wang HM, Tsai CY, Chao TH. Surgical treatment for rectal prolapse. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi (Taipei) 2001;64:95–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boccasanta P, Venturi M, Reitano MC, Salamina G, Rosati R, Montorsi M, et al. Laparotomic vs. laparoscopic rectopexy in complete rectalprolapse. Dig Surg. 1999;16:415–9. doi: 10.1159/000018758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heah SM, Hartley JE, Hurley J, Duthie GS, Monson JR. Laparoscopic suture rectopexy without resection iseffective treatment for full-thickness rectal prolapse. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:638–43. doi: 10.1007/BF02235579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kellokumpu IH, Kairaluoma M. Laparoscopic repair of rectal prolapse: Surgical technique. Ann Chir Gynaecol. 2001;90:66–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siproudhis L, Bellisant E, Juguet F, Mendler MH, Allain H, Bretagne JF, et al. Rectal adaptation to distension in patients with overt rectal prolapse. Br J Surg. 1998;85:1527–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aitola PT, Hiltunen KM, Matikainen MJ. Functional results of operative treatment of rectal prolapse over an 11-year period: Emphasis on transabdominal approach. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:655–60. doi: 10.1007/BF02234145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Briel JW, Schouten WR, Boerma MO. Long-term results of suture rectopexy in patients with fecal incontinence associated with incomplete rectal prolapse. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:1228–32. doi: 10.1007/BF02055169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hiltunen KM, Matikainen MJ, Auvinen O, Hietanen P. Clinical and manometric evaluation of anal sphincter function in patients with rectal prolapse. Am J Surg. 1986;151:489–92. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(86)90110-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keighley MR, Fielding JW, Alexander-Williams J. Results of Marlex mesh abdominal rectopexy for rectal prolapse in 100 consecutive patients. Br J Surg. 1983;70:229–32. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800700415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuijpers HC. Treatment of complete rectal prolapse: To narrow, to wrap, to suspend, to fix, to encircle, to plicate or to resect? World J Surg. 1992;16:826–30. doi: 10.1007/BF02066977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nicholls RJ. Rectal prolapse and the solitary ulcer syndrome. Ann Ital Chir. 1994;65:157–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yakut M, Kaymakciioglu N, Simsek A, Tan A, Sen D. Surgical treatment of rectal prolapsed. A retrospective analysis of 94 cases. Int Surg. 1998;83:53–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Purkayastha S, Tekkis P, Athanasiou T, Aziz O, Paraskevas P, Ziprin P, et al. A comparison of open vs laparoscopic abdominal rectopexy for full thickness rectal prolapse: A meta-analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;46:1930–40. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0077-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim DS, Tsang CB, Wong WD, Lowry AC, Goldberg SM, Madoff RD. Complete prolapse rectum: Evolution of management and results. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:460–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02234167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deen KI, Grant E, Billingham C, Keighley MR. Abdominal resection rectopexy with pelvic floor repair for full thickness rectal prolapse. Br J Surg. 1994;81:302–4. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graf W, Karlbom U, Pahlman L, Nilsson S, Ejerblad S. Functional results after abdominal suture rectopexy for rectal prolapse or intussusception. Eur J Surg. 1996;162:905–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Madiba TE, Baig MK, Wexner SD. Surgical management of rectal prolapse. Arch Surg. 2005;140:63–73. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.140.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gourgiotis S, Baratsis S. Rectal prolapse. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:231–43. doi: 10.1007/s00384-006-0198-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bruch HP, Herold A, Schiedeck T, Schwander O. Laparoscopic surgery for rectal prolapse and outlet obstruction. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:1189–94. doi: 10.1007/BF02238572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Graf W, Stefannson T, Arvidsson D, Pahlman L. Laparoscopic suture rectopexy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:211–2. doi: 10.1007/BF02052454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Speakman CT, Madden MV, Nicholas RJ, Kamm KA. Lateral ligament division during rectopexy causes constipation but prevents recurrence: Results of a prospective randomized study. Br J Surg. 1991;78:1431–3. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800781207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scaglia M, Fasth S, Hallgren T, Nordgren S, Oresland T, Hulten L. Abdominal rectopexy for rectal prolapse: Influence of surgical technique on functional outcome. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:805–13. doi: 10.1007/BF02050146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]