Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

To assess the feasibility of laparoscopic surgery in cases of moderate-severe endometriosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

A prospective study was carried out in a tertiary centre over a period of 2 years. Moderate to severe endometriosis was defined by revised American fertility society (rAFS) classification (41 patients). Various procedures were done to provide symptomatic relief. Feasibility of laparoscopic surgery and various patient parameters were analysed.

RESULTS:

Various procedures like adhesiolysis in POD, excision of endometriomas, resection of endometriotic nodules in the recto-vaginal septum, ureterolysis and total laparoscopic hysterectomy with/ without oophorectomy were done. Majority of patients underwent cystectomy for endometriomas (53.6%) or adhesiolysis with excision of endometriotic nodule (36.5%). Total laparoscopic hysterectomy with or without ooperectomy was done in 31.7% patients. Of the total 9 patients with primary infertility and moderate-severe endometriosis, 5 patients (55.5%) conceived after surgery.

CONCLUSION:

There is good evidence that in experienced hands laparoscopic surgery helps in long-term symptomatic relief, improves pregnancy rates and reduces recurrence of disease with largely avoiding complications.

Keywords: Endometriosis, feasibility, laparoscopic excision

INTRODUCTION

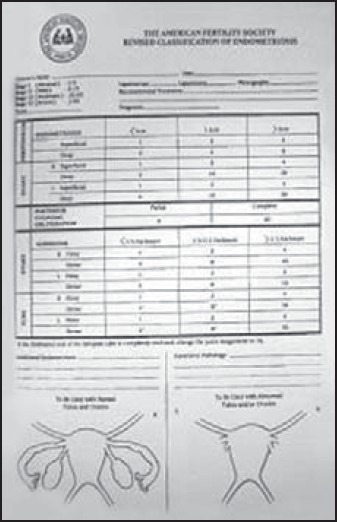

Endometriosis is the presence of endometrial glands or stroma in sites other than the uterine cavity. This condition is characterized by variable clinical manifestations and surgical appearance and often there is poor correlation between the two. Although there are many diagnostic tests available like imaging studies and blood tests like CA-125, none of them are confirmatory. The gold standard diagnostic test is direct visualization of lesions by either laparotomy or laparoscopy. The revised American fertility society (rAFS) classification provides a scoring system based on the visual findings at laparoscopy which defines the severity of endometriosis [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

rAFS classification

Moderate and severe endometriosis is defined by rAFS classification as endometriosis with a score of 16-40 and 40 or more, respectively. In patients with severe endometriosis, lesions usually involve the posterior cul-sac, anterior rectum, one or both pelvic side walls involving ureters, rectosigmoid and less commonly anterior bladder, appendix, and small bowel. Deep, fibrotic endometriotic deposits can usually be palpated clinically in such cases of extensive endometriosis. Laparoscopically, there may be presence of extensive adhesions with distortion of pelvic anatomy in such cases. The cul-de sac may be completely obliterated, rectum stuck to the posterior surface of cervix and vagina and the ureters may be involved causing hydronephrosis. As there is such extensive involvement, thorough and lengthy surgical procedures may be required in these cases of endometriosis.

Laparoscopy as a method of treatment offers certain advantages and we aim to evaluate in this study the efficacy of laparoscopy as the surgical procedure of choice for such conditions. Also we would define the associated characteristics of the lesions and follow-up results.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This prospective study was carried out in a tertiary center over a period of 2 years. A total of 100 women with provisional diagnosis of endometriosis were taken up for laparoscopy. The following patients were counselled for laparoscopic evaluation:

Patients having signs and symptoms suggestive of endometriosis like chronic pelvic pain, dysmenorrhoea, dyspareunia, and infertility.

Clinical findings on per-vaginum/per-rectal examination suggestive of endometriosis.

Ultrasound findings suggestive of endometriomas.

Patients with other investigations like IVP, MRI suggestive of recto-vaginal endometriosis.

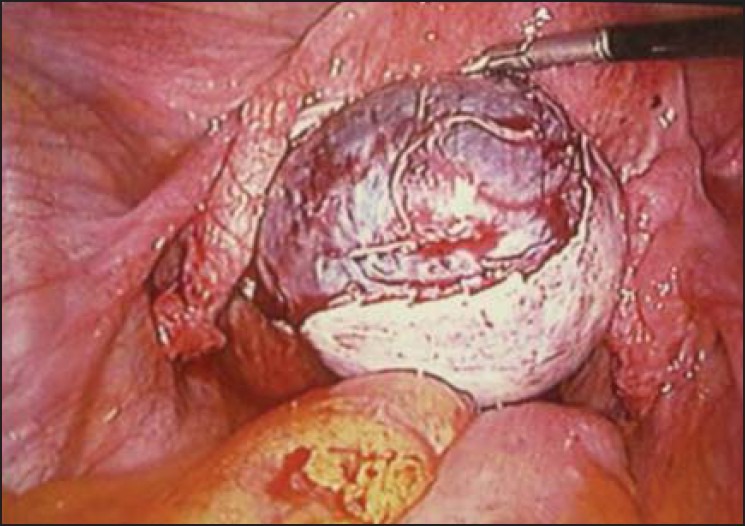

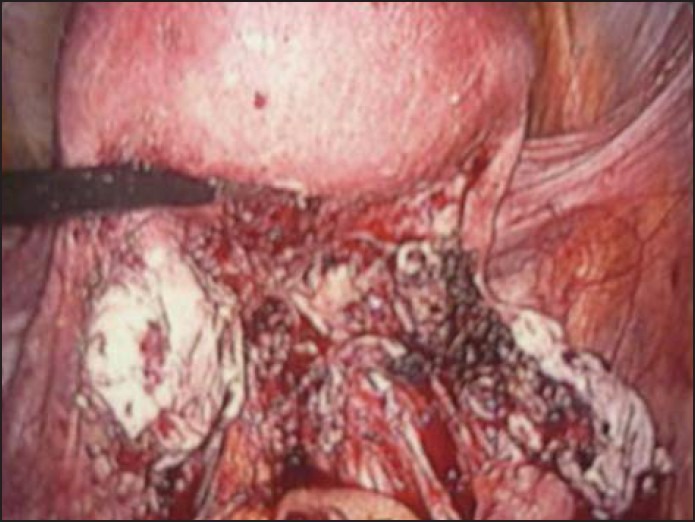

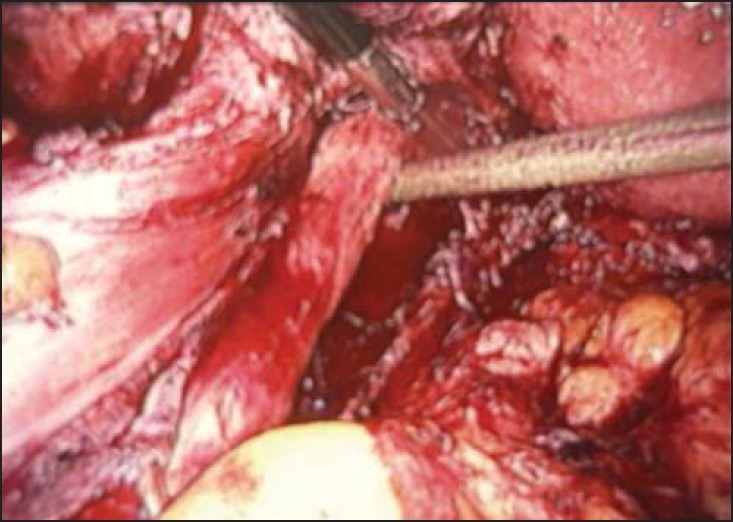

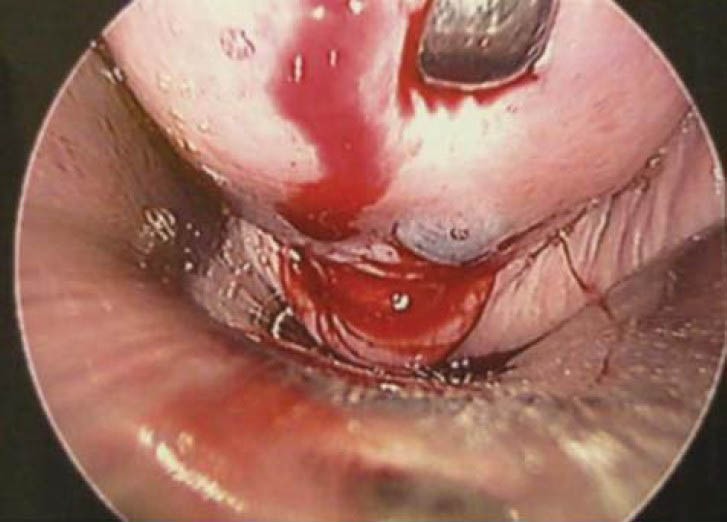

In these women moderate to severe endometriosis was defined by rAFS classification. All patients in stage III and stage IV of rAFS classification i.e., score of 16 or more were included in the series (37 patients). Women with extensive endometriosis involving the ureters, bowel, or bladder but with no peritoneal endometriosis were also included in the series even though they had low rAFS scores (4 patients). Thus a total of 41 women were included in the series. In these women operative laparoscopy along with definitive treatment of the endometriotic lesions was planned at the same setting. The various procedures done for women with moderate to severe endometriosis included excision of endometriomas [Figure 2], adhesiolysis in POD [Figure 3], excision of endometriotic nodules on uterosacral ligaments and vagina, resection of endometriotic nodules on rectum, ureterolysis [Figure 4], and total laparoscopic hysterectomy with or without oophorectomy.

Figure 2.

Cystectomy for endometrioma

Figure 3.

Adhesiolysis in POD

Figure 4.

Ureterolysis

The primary outcome measure was the feasibility of laparoscopic surgery in cases of moderate to severe endometriosis. The secondary outcome measures included operating time, blood loss, conversion to laparotomy, bladder, bowel, ureteric injury, analgesic requirement of the patient postoperatively, recovery period, and patient satisfaction with the procedure.

Also various patient parameters like symptomatology, clinical findings, and their correlation with laparoscopic findings were analysed.

OBSERVATIONS AND RESULT

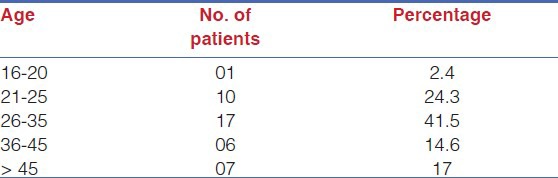

In the present study, 41 women presenting with varied symptomatology were found to have stage III /IV endometriosis. Table 1 gives the distribution of age among the women presenting with the moderate to severe endometriosis.

Table 1.

Distribution of age among the women presenting with the moderate to severe endometriosis

As seen in Table 1, the distribution of patients varied between different age groups with maximum patients in age group of 20-35 years. The youngest patient had severe endometriotic lesions and was a young unmarried girl of 19 years and the oldest patient was 46-years old.

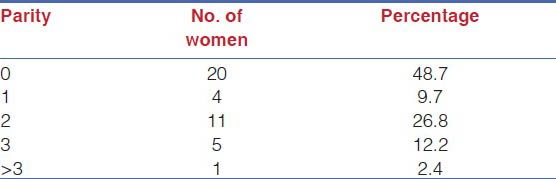

Table 2 gives the comparison between the parity and number of women presenting with moderate to severe endometriosis

Table 2.

Comparison between the parity and number of women presenting with moderate to severe endometriosis

As can be seen from the Table 2, majority of these cases were seen in women who were nulliparas (48.7%). Of the four women who were primiparas, two had a previous history of primary infertility but conceived spontaneously.

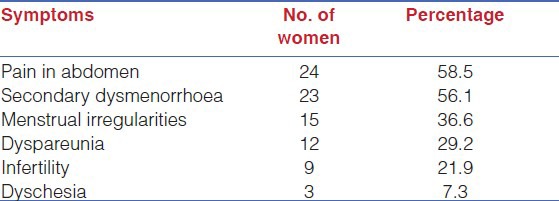

Table 3 gives the distribution of the symptomatology among the women presenting with the moderate to severe endometriosis.

Table 3.

Distribution of the symptomatology among the women presenting with the moderate to severe endometriosis

As seen in the Table 3, although a patient can present with a number of symptoms, majority of the women in our study presented with pain in lower abdomen (58.5 %) and secondary dysmenorrhoea (56.1 %). Majority of women who presented with dysmenorrhoea and dyspareunia were mostly found to have endometriosis involving the pouch of Douglas, the rectovaginal septum and the uterosacral ligaments. Majority of patients with infertility presented with endometriomas in the ovary along with superficial peritoneal involvement.

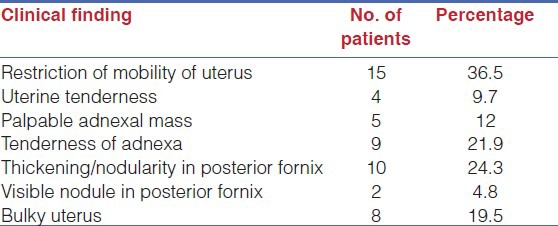

Table 4 gives the distribution of the clinical features among the patients presenting with moderate to severe endometriosis

Table 4.

Distribution of the clinical features among the patients presenting with moderate to severe endometriosis

As seen from Table 4, majority of the patients present with restriction of mobility of uterus (36.5%), thickening in the posterior fornix (24.3%) or tenderness in the adnexa (21.9 %). Endometriosis is also commonly associated with adenomyosis of the uteri, clinically seen as bulky uterus (19.5% patients). Two patients also had a visible bluish nodule in the posterior fornix indicating endometriotic involvement of the vagina [Figure 5]. This makes per-speculum examination a very important component of examination for endometriosis. Per rectal and combined per rectal/ pervaginum examination is also to be done in all patients to look for the involvement of POD, nodularity of uterosacral ligaments and involvement of rectum.

Figure 5.

Bluish endometriotic nodule in posterior fornix

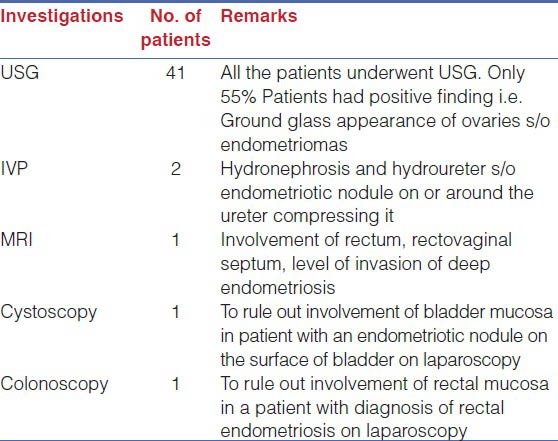

Table 5 gives the distribution of various investigations done.

Table 5.

Distribution of various investigations done

As seen from [table 5], though USG was done in all patients, positive findings suggestive of endometriosis were found in only 55% of the patients. The findings that suggest endometriosis on ultrasound include ground glass appearance of ovaries (endometrioma) but USG has a limited role in the diagnosis of adhesions or superficial peritoneal implants. In patients where endometriosis involving the rectum, ureter or bladder is suspected based on clinical symptoms, other investigations like MRI, IVP, colonoscopy, or cystoscopy may be needed to provide additional information.

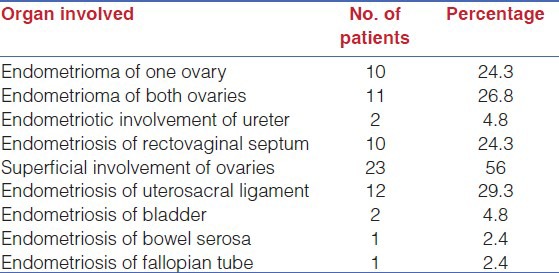

Table 6 gives the distribution of various organ involvements in moderate to severe endometriosis

Table 6.

Distribution of various organ involvements in moderate to severe endometriosis

As seen from Table 6, patients with moderate to severe endometriosis had severe organ involvement of not only ovaries and uterosacral ligaments but also of adjacent organs like ureters (4.8%), bowel (2.4%) and bladder (4.8%).

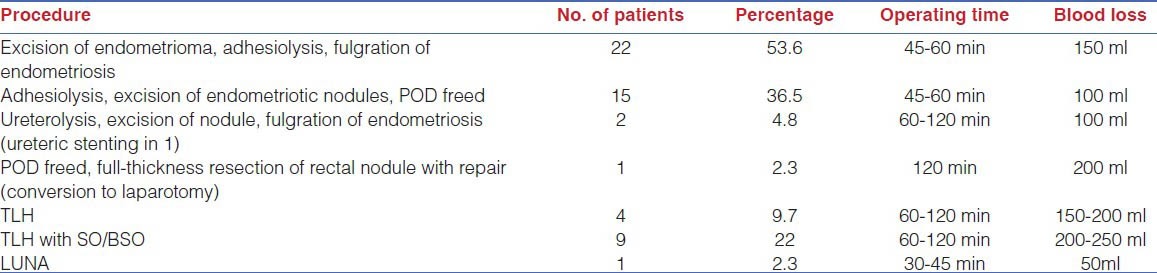

Table 7 gives the distribution of various laparoscopic procedures done, operating time, and blood loss in cases of moderate to severe endometriosis.

Table 7.

Distribution of various laparoscopic procedures done, operating time and blood loss in cases of moderate to severe endometriosis

As seen from Table 7, majority of patients underwent cystectomy for endometrioma (53.6%) or adhesiolysis with excision of the endometriotic nodule (36.5%). This is because majority of patients belonged to younger age group with either infertility or desired preservation of the uterus and the adnexa. Such precise surgery with minimal tissue handling is better performed laparoscopically. Many such patients had endometriomas of ovaries as well as adhesions in POD and required both procedures. Total laparoscopic hysterectomy with or without ooperectomy was done in older patients with endometriosis (31.7%). The operating time varied for most procedures between 60 minutes to 120 minutes. This is in comparison to conventional laparotomy. Certain procedures like ureterolysis, adhesiolysis and resection of rectal nodules take up more time because of extensive dissection and vital organs involved.

Also, blood loss in all procedures was minimal varying between 100 ml 200ml. This is because precise haemostasis is possible in laparoscopic surgery with use of energy sources like bipolar, vessel sealing devices, and harmonic.

Complications

There were no major intraoperative or postoperative complications in all 41 patients. One patient required conversion to laparotomy. This patient had an endometriotic nodule invading the rectum. Open surgery with excision of the rectal wall along with the nodule was done as expertise to treat this laparoscopically was not available. One patient with an endometriotic nodule infiltrating upto the bladder mucosa refused a cystostomy and was put on suppressive therapy. There were no complications in form of injury to the ureters, bladder, rectosigmoid, or small bowel. Thus in expert hands even for difficult cases of severe endometriosis, laparoscopy is a very safe procedure.

Of the 41 patients, 63% were operated on day care basis and were discharged the same day. These mainly included patients with infertility and moderate endometriosis. Thirty-seven percent patients were discharged on day 2 postoperatively. These mainly included patients undergoing total laparoscopic hysterectomy and those undergoing extensive resection for endometriosis. All the patients were discharged on oral antibiotics and oral analgesics. This is in contrast to open surgery where patient might require 2-3 day stay in the hospital and injectable antibiotics and analgesics for a longer duration.

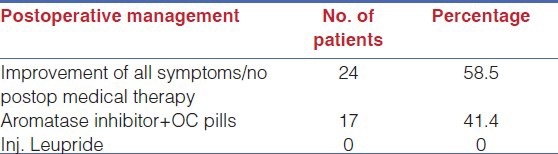

Table 8 gives the distribution of degree of resolution of symptoms and postoperative medical management if required.

Table 8.

Distribution of degree of resolution of symptoms and postoperative medical management if required

As seen from Table 8, 58.5 % patients had full resolution of symptoms and no postoperative medical therapy was required. 41.4% i.e., 17 patients were put on aromatase inhibitor with OC pill therapy for 6-9 months postoperatively. These were generally patients in younger age group who did not want treatment for fertility at present and were put on post operative suppression therapy. The author does not favour medical therapy with GnRH agonist because of the associated side effects and incomplete suppression in extra-gonadal areas. Patients who had associated adenomyosis of the uterus but were of younger age group or nulligravidas and wanted preservation of uterus were put on additional medical therapy. Those patients with severe endometriosis and infertility were immediately sent for ART procedures postoperatively as the chances of conception are highest immediate 6 months postoperative.

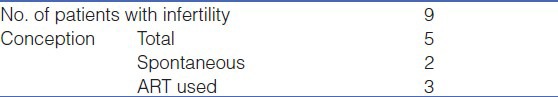

Table 9 gives the distribution of cases of infertility and conception rates up to 6 months postoperatively.

Table 9.

Distribution of cases of infertility and conception rates up to 6 months postoperatively

As seen from Table 9, of the total 9 patients with infertility, 5 conceived (55.5%). Of these 40% had a spontaneous conception and 60% had to undergo an ART procedure.

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of endometriosis among women of child bearing age group according to various studies is between 5 and 15%.[1,2,3] The distribution between various stages has been found to be as: stage I, 32.5%; II, 9.3%, III, 1.1%; IV, 2.3% in one study.[4] In our study, 41% women were found to have stage III/IV endometriosis. This may be because the study was conducted in a tertiary referral centre. Its prevalence in infertile population is around 20-48%. In our study 21.9% women were found to be suffering from infertility.

The clinical manifestation of endometriosis is varied and most studies have shown contradictory results between type and site of endometriotic lesions, disease stage and frequency and severity of pelvic symptoms.[5] Dysmenorrhoea, the symptom most frequently reported by women with endometriosis, has been variably found to be associated with early, papular, and atypical implants,[6] advanced disease stages[7] and AFS classification score but not stage.[8] The only strong association observed by most investigators is between deep posterior cul-de-sac lesions and dyspareunia.[9] In our present study secondary dysmenorrhoea, pain in lower abdomen and dyspareunia were the three most common symptoms. Those patients with severe dyspareunia and dysmenorrhoea had deep infiltrating lesions in POD and adhesions and fibrosis of uterosacral ligaments. Patients presenting with utereric, bladder or bowel endometriosis had low scores but extensive disease on laparoscopy. The low scores were due to paucity of peritoneal disease.

Diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis by laparoscopy requires a surgeon with expertise in laparoscopic surgery as endometriosis can present with classic lesions as well as have non-classical appearance. In many patients only fibrosis or adhesions may be seen on initial evaluation and diagnosis of endometriosis can be totally missed. For example, there may be an endometriotic collection in the rectovaginal septum and it may present as adhesions of rectum to POD and fibrosis of uterosacral ligaments. Unless extensive adhesiolysis is done and fibrotic lesions excised, one may miss the lesion and cannot offer complete symptom relief to the patient. In such situations laparoscopy provides an ideal setup with its benefits of good visualization of pelvic anatomy and magnification. This helps to identify non-classic lesions and visualize clearly the lesions on bladder, bowel, ureters, and POD. Also, there is minimum tissue handling and desiccation and precise haemostasis during laparoscopy. Thus the chances of adhesions postoperatively are less. Minimal suturing and small incisions on the abdomen leads to minimal postoperative pain and faster patient recovery.

In comparison, visualization at laparotomy is inadequate due to restricted space and presence of the recto-sigmoid. Also, at laparotomy smaller lesions may not be visualized and thus not treated. These patients may not have symptomatic relief or have a higher chance of recurrence. Medical therapy can also be offered to patients of endometriosis but the disadvantages are many. These include hypoestrogenic effects and recurrence of endometriosis as soon as the therapy is stopped. Also the drugs need to be taken daily and for longer duration and hence is inconvenient to the patient. Surgery on the other hand offers complete resection of endometriotic lesions and hence total symptom relief. This can be done either at laparotomy or by laparoscopy.

In the present study laparoscopy remains the modality of choice for diagnosis, staging as well as treatment of moderate to severe endometriosis.

The aim of surgical treatment in cases of severe endometriosis is to remove all apparent endometriotic disease from the pelvis as far as possible to provide patient with a symptom-free life. The surgical treatment in severe endometriosis varies according to patient's age, fertility status, symptomatology and desires. Thus a variety of procedures can be done as seen in the study. Infertility requires special care even in cases of severe endometriosis and the surgeon is not to be very aggressive so as to spare the ovarian reserve in such patients.[10] Such patients are immediately sent for ART procedures. Pregnancy rates have been shown to be highest in first 6 months after surgery in the present study and many others.[11] It is to be stressed that surgical treatment for severe endometriosis requires a planned multi-speciality effort. Help of expert colorectal surgeon and urologist should be sought for a better patient management, if required.

Endometriosis involving the urologic system also deserves a special mention here as it is a rare and silent disorder that can lead to renal failure. Involvement of the bladder, ureter, kidney, and urethra is 85, 10, 4, and 2%, respectively.[12] Only a high index of suspicion and imaging studies like renal USG and IVP can help in diagnosis. Ureteric endometriosis is usually extrinsic because of proximity of ureters to the uterosacral ligaments and hence can be involved in fibrosis of uterosacral ligaments. Recent studies suggest that laparoscopic ureterolysis can be an effective treatment option in most patients with ureteral endometriosis.[13] Successful application of laparoscopic surgery, even for procedures that have traditionally necessitated laparotomy, has been reported. Extensive experience with endourological techniques is prerequisite for success.[14] Systematic ureteric stenting prior to surgical dissection of the pelvic wall is recommended in patients. Our study reported two such cases. One case was of a 19-year-old unmarried girl with a history of previous left nephrectomy for severe hydronephrosis presenting with dysmenorrhoea, right flank pain and mass in right iliac fossa. IVP showed right hydronephrosis and on laparoscopy right ureteric nodule constricting the ureter with right endometrioma was seen. Both were excised and patient is pain-free now with normal renal functions.

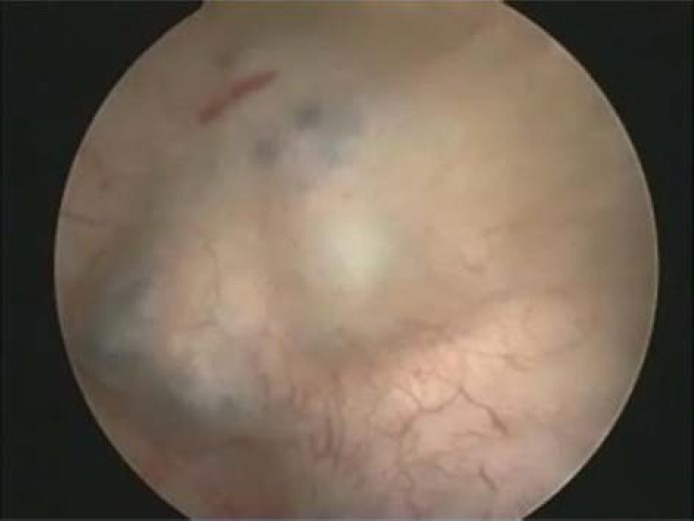

Second case was of a 30-year-old woman with recurrent endometriosis who was found to have extensive peritoneal endometriosis with a large endometrioma. The bladder was adherent to the ovarian mass and could not be separated. On cystoscopy a 2-cm endometriotic nodule was found protruding in bladder mucosa [Figure 6]. The patient, however, refused cystostomy and excision of nodule and was put on long-term medical suppression therapy.

Figure 6.

Bladder endometriosis

The present study reports no major complications, either early or delayed postoperatively in the patients. One patient was converted to laparotomy as she had extensive endometriosis involving the rectum and open surgery with excision of lesion was considered a better option. This was a case of 35-year patient with primary infertility who presented with dysmenorrhoea, dyspareunia, and dyschezia. On laparoscopy, POD was obliterated with uterosacral infiltration. On adhesiolysis the disease was found to extend in rectum upto muscularis. The case was then converted to laparotomy where full-thickness resection of rectum with repair was done. Although the case was done by laparotomy, we have the availability of circular staplers laparoscopically and an expert colorectal surgeon can perform such procedures laparoscopically.

Thus it can be concluded that surgical treatment of severe endometriosis by laparoscopy is the treatment of choice now with the availability of expertise and precise surgical equipments. With various clinical presentations, a risk of recurrence and involvement of vital organs in an increasing younger population, subjecting them to laparotomy is unnecessary and uncalled for. Laparoscopy in expert hands offers optimal results even in extensive tissue involvement and should be the first option.

CONCLUSIONS

Endometriosis is an enigmatic disease. Severe endometriosis poses a challenge for a surgeon and is technically demanding but the rewards for patients are high. There is good evidence that in experienced hands laparoscopic surgery helps in long term symptomatic relief, improves pregnancy rates and reduces recurrence of disease with largely avoiding major complications.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Leyendecker G, Herbertz M, Kunz G, Mall G. Endometriosis results from the dislocation of basal endometrium. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:2725–36. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.10.2725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bulun SE. Endometriosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:268–79. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leyendecker G, Kunz G, Noe M, Herbertz M, Mall G. Endometriosis: A dys-function and disease of the archimetra. Hum Reprod Update. 1998;4:752–62. doi: 10.1093/humupd/4.5.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rawson JM. Prevalence of endometriosis in asymptomatic women. J Reprod Med. 1991;36:513–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whiteside JL, Falcone T. Endometriosis-related pelvic pain: What is the evidence? Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2003;46:824–30. doi: 10.1097/00003081-200312000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vercellini P, Bocciolone L, Vendola N, Colombo A, Rognoni MT, Fedele L. Peritoneal endometriosis: Morphologic appearance in women with chronic pelvic pain. J Reprod Med. 1991;36:533–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fedele L, Bianchi S, Bocciolone L, Di Nola G, Parazzini F. Pain symptoms associated with endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;79:767–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muzii L, Marana R, Pedullà S, Catalano GF, Mancuso S. Correlation between endometriosis-associated dysmenorrhea and the presence of typical or atypical lesions. Fertil Steril. 1997;68:19–22. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(97)81469-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vercellini P, Trespidi L, De Giorgi O, Cortesi I, Parazzini F, Crosignani PG. Endometriosis and pelvic pain: Relation to disease stage and localization. Fertil Steril. 1996;65:299–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yazbeck C, Madelenat P, Sifer C, Hazout A, Poncelet C. Ovarian endometriomas: Effect of laparoscopic cystectomy on ovarian response in IVF-ET cycles. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2006;34:808–12. doi: 10.1016/j.gyobfe.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuchs F, Raynal P, Salama S, Guillot E, Le Tohic A, Chis C, et al. Reproductive outcome after laparoscopic treatment of endometriosis in an infertile population. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris) 2007;36:354–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jgyn.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abeshouse BS, Abeshouse G. Endometriosis of the urinary tract. J Int Coll Surg. 1960;4:43–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seracchioli R, Mabrouk M, Manuzzi L, Guerrini M, Villa G, Montanari G, et al. Importance of retroperitoneal ureteric evaluation in cases of deep infiltrating endometriosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15:435–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghezzi F, Cromi A, Bergamini V, Serati M, Sacco A, Mueller MD. Outcome of laparoscopic ureterolysis for ureteral endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:418–22. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.12.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]