Abstract

Laparoscopic posterior mesh rectopexy (LPMR) is now an accepted surgical treatment for complete rectal prolapse. It is associated with complications such as partial mucosal prolapse, fecal impaction, constipation, and rarely recurrence. Erosion of the mesh into the rectum after LPMR is very rare. We report herein the case of 40-year-old man who presented with mesh erosion into the rectum and managed successfully by the laparoscopic excision of mesh. This is probably the first such case managed by the laparoscopic approach.

Keywords: Laparoscopic posterior mesh rectopexy, mesh erosion, rectal prolapse

INTRODUCTION

Laparoscopic posterior mesh rectopexy (LPMR) is a good surgical option for rectal prolapse with low morbidity and mortality.[1] Specific complication like mesh erosion into the rectum following LPMR is very rare with only one such case, in which mesh got expelled via rectum, reported in literature till date.[2] We report a case of mesh erosion into the rectum after LPMR which was managed with laparoscopic mesh removal and review the published literature.

CASE REPORT

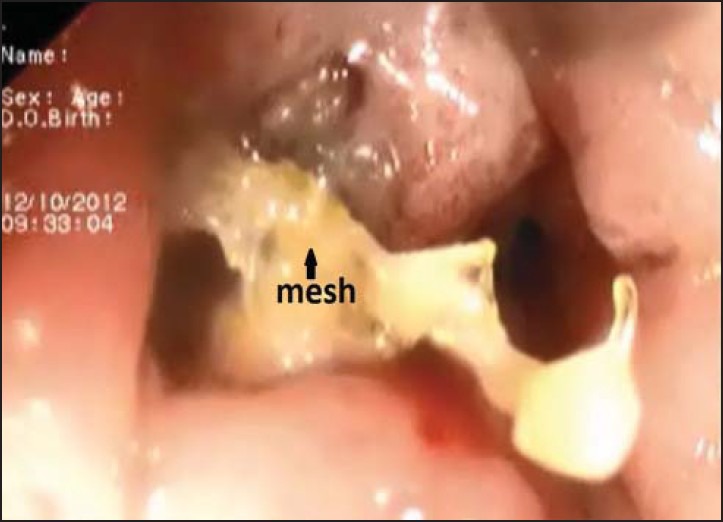

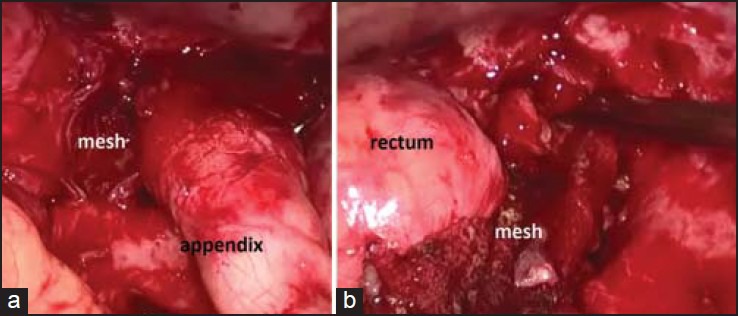

A 40-year-old man presented with occasional bleeding per rectum since 10 months with low grade intermittent fever for 1 week. He had history of LPMR for complete rectal prolapse 2 years back, carried out elsewhere. His abdominal and per rectal examinations were unremarkable. Sigmoidoscopy revealed hyperemic mucosa with ulceration 15 cm from anal verge, with a part of the polypropylene mesh projecting into the rectum [Figure 1]. Computed tomography (CT) scan of abdomen showed asymmetric anterior wall thickening of rectosigmoid junction with fat stranding and minimal fluid collection. Review of his surgical notes revealed that a 15 cm × 10 cm polypropylene mesh was used for rectopexy. Since it was a large mesh fixed with multiple tacks and possible dense adhesions, transanal approach was not attempted. Under general anesthesia, in lithotomy position, diagnostic laparoscopy was done. There were multiple dense adhesions in the pelvis. After sharp adhesiolysis, folded, and densely adherent polypropylene mesh was identified. Appendix was inflamed with its tip densely adherent to the mesh [Figure 2]. Excision of the mesh with appendectomy was done. There was a small rectal perforation at the site of erosion, which was confirmed by air leak test. Tube drain was kept into pelvis and diverting ileostomy was performed. He had an uneventful recovery with the ileostomy functioning from 2nd day. Patient was discharged with the drain on the 4th day. The drain was removed after 2 weeks. Distal loopogram was carried out after 3 months, which showed no leak. Subsequently ileostomy closure was done.

Figure 1.

Sigmoidoscopic appearance of mesh erosion into rectum

Figure 2.

Intra-operative images of (a) tip of appendix adherent to the mesh and (b) mesh eroding into rectum

DISCUSSION

The first laparoscopic rectopexy was reported in 1993.[3] Laparoscopic rectopexy is presently the preferred management approach for rectal prolapse as it has better results especially in terms of less post-operative pain, shorter hospital stay, and similar recurrence rate as open rectopexy.[1] LPMR is preferred for complete rectal prolapse without constipation.

Mesh erosion is a very rare complication after LPMR. It may present with discharge of pus or blood per rectum, even several months or years after surgery. It can be evaluated by doing a flexible sigmoidoscopy, which will usually reveal an ulcerated lesion at the site of erosion with visualization of mesh. CT scan of abdomen with contrast helps in localizing the mesh in relation to rectum as well as pelvic collection, if any.

Mesh erosion following female pelvic floor reconstructions have been extensively studied.[4] It is thought to be associated with the type of mesh used. It is less common with type I mesh when compared to type II, III, and IV meshes due to bigger pore size with lesser chance of infection.[4] Other factors that are found significant are poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, tobacco use, prior history of pelvic irradiation, and repeat procedures, which contribute to poor wound healing and subsequent infection, erosion or extrusion.[4] Same causes can be considered as possible etiologies for mesh erosion after LPMR as well. Certain surgical technical errors like unrecognized rectal injury and deeper stitches through the rectum may also contribute to mesh erosion. Bigger sized mesh which can produce more folding after fixation, as in our case, may be a possible cause for erosion. Ideal mesh size for posterior rectopexy is 6 cm × 4 cm.[5] Another possible cause in our case could be infection of mesh due to adhesion of inflamed appendix to it.

Mesh erosion can be managed by transanal or laparoscopic approaches. Since, the incidence is very rare, no definite protocol regarding management is available in literature. We preferred laparoscopic approach in our case, as it was too big mesh to remove through transanal approach. Moreover, only a part of mesh was protruding into the rectal lumen and it was fixed with multiple tacks to the sacrum. Severe inflammation and friable tissues precludes primary repair of the rectal defect where diverting ileostomy or colostomy plays an important role.

In summary, mesh erosion into rectum following LPMR is very rare. The predisposing factors could be mesh infection, larger mesh, and unrecognized rectal injuries. Complete excision of the mesh is the definitive management. Laparoscopic excision of mesh is a feasible and promising approach to manage such an unusual complication following LPMR.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kairaluoma MV, Viljakka MT, Kellokumpu IH. Open vs. laparoscopic surgery for rectal prolapse: A case-controlled study assessing short-term outcome. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:353–60. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6555-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hernández P, Targarona EM, Balagué C, Martínez C, Pallares JL, Garriga J, et al. Laparoscopic treatment of rectal prolapse. Cir Esp. 2008;84:318–22. doi: 10.1016/s0009-739x(08)75042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Munro W, Avramovic J, Roney W. Laparoscopic rectopexy. J Laparoendosc Surg. 1993;3:55–8. doi: 10.1089/lps.1993.3.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nazemi TM, Kobashi KC. Complications of grafts used in female pelvic floor reconstruction: Mesh erosion and extrusion. Indian J Urol. 2007;23:153–60. doi: 10.4103/0970-1591.32067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nivatvongs S, Young-Fadok TM. Rectal prolapse: Abdominal approach. In: Fischer JE, Bland KI, editors. Mastery of Surgery. 5th ed. II. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. pp. 1582–90. [Google Scholar]