Abstract

The current study used model-based cluster analyses to determine if there are two distinct variants of adolescents (ages 11 - 18) high on callous-unemotional (CU) traits that differ on their level of anxiety and history of trauma. The sample (n = 272) consisted of clinic-referred youths who were primarily African-American (90%) and from low income families. Consistent with hypotheses, three clusters emerged, including a group low on CU traits, as well as two groups high on CU traits that differed in their level of anxiety and past trauma. Consistent with past research on incarcerated adults and adolescents, the group high on anxiety (i.e., secondary variant) was more likely to have histories of abuse and had higher levels of impulsivity, externalizing behaviors, aggression, and behavioral activation. In contrast, the group low on anxiety (i.e., primary variant) scored lower on a measure of behavioral inhibition. On measures of impulsivity and externalizing behavior, the higher scores for the secondary cluster only were found for self-report measures, not on parent-report measures. Youths in the primary cluster also were perceived as less credible reporters than youth in the secondary or cluster low on CU traits. These reporter and credibility differences suggest that adolescents within the primary variant may underreport their level of behavioral disturbance, which has important assessment implications.

Keywords: Callous Unemotional Traits, Secondary Psychopathy, Trauma, Aggression, Adolescents

Cleckley (1941/1976) described psychopathy as a constellation of interpersonal, affective, and behavioral personality features. Individuals with high levels of psychopathic traits are characterized by a superficial and manipulative interpersonal style, a profound lack of empathy/remorse, frequent impulsivity and irresponsibility, and socially deviant behavior or antisociality. Adults with psychopathic traits represent a minority or distinct subgroup of antisocial individuals (Hare, Hart, & Harpur, 1991; Hart & Hare, 1997) but they are a subgroup that seems to show a particularly severe and chronic pattern of antisocial behavior (Hart, Knopp, & Hare, 1988; Hemphill, Hare, & Wong, 1998; Kosson, Smith, & Newman, 1990). The affective features of psychopathy, also referred to as callous-unemotional (CU) traits (e.g. lack of empathy/remorse, shallow affect, callousness), constitute a core component of psychopathy, (Cleckley, 1976; Hart & Hare, 1996) and are frequently studied among youth populations as a downward extension of psychopathy (Frick, 2009). In support of this extension, there is evidence to suggest CU traits in childhood and adolescence are predictive of psychopathy in adulthood, even after controlling for conduct disorder and other childhood risk factors (Burke, Loeber, & Lahey, 2007; Lynam, Caspi, Moffitt, Loeber, & Stouthamer-Loeber, 2007).

Similar to adults with high levels of psychopathic traits, youth with CU traits are thought to demarcate a unique subgroup of antisocial youth whose behavior tends to be more severe and violent in nature. For example, recent qualitative (Frick & Dickens, 2006; Frick & White, 2008; Pardini & Fite, 2010) and quantitative (Edens, Campbell, & Weir, 2007; Leistico, Salekin, Decoster, & Rogers, 2008) reviews indicate psychopathic or CU traits predict a more severe, stable, and aggressive pattern of behavior in antisocial youth. In addition, antisocial youths with CU traits show a large number of genetic, neurocognitive, emotional, personality, and social differences compared to antisocial youths without these traits (see Frick & Viding, 2009; Frick & White, 2008, for reviews). Further, youth with CU traits often respond differently to treatment interventions compared to antisocial youths without these traits (Haas et al., 2011; Hawes & Dadds, 2005).

Given the extensive empirical evidence to support the utility of CU traits for designating an important subgroup of antisocial youths, the DSM-5 ADHD and Disruptive Behavior Disorders Work Group has proposed the addition of a specifier to the diagnosis of Conduct Disorder to designate those who also show significant levels of CU traits (Frick & Nigg, 2012). Recent research in community and clinic samples suggests this specifier may impact anywhere between 10 to 50% of children or adolescents diagnosed with Conduct Disorder (CD), depending on the informant or informants used to assess the CU traits (Kahn, Frick, Youngstrom, Findling, & Youngstrom, 2012; Rowe et al., 2010). As a result of this potential inclusion of CU traits in diagnostic classification, research is needed to further understand the potential causes of CU traits, the characteristics of persons with CU traits, and the implications of these causes and characteristics for guiding optimal assessment and treatment practices. One especially important focus of research is whether there are distinct developmental pathways that can lead to CU traits.

Variants of Psychopathy in Adults

While psychopathy has historically been viewed as a homogenous construct, a recent review of seminal theories and empirical work provides compelling evidence to suggest there may be distinct variants of psychopathy with potentially different etiologies (Skeem, Poythress, Edens, Lilienfeld, & Cale, 2003). Karpman (1941, 1948) proposed an influential theory of psychopathy subtypes, which included a primary and secondary variant. Specifically, Karpman (1941, 1948) theorized an innate or heritable affective deficit was characteristic of primary psychopathy, while the affective deficit within secondary psychopathy was a product of adaptation to environmental factors such as parental rejection, abuse, or trauma. There has been a substantial amount of research supporting this general model. Specifically, research on adults suggests that individuals high on psychopathy can be meaningfully split into two distinct groups based on the level of trait anxiety and only the group low on anxiety (i.e., primary psychopathy) show deficits in laboratory tasks measuring passive avoidance (Arnett, Smith, & Newman, 1997; Newman & Schmitt, 1988) and in responses to emotional stimuli (Hiatt, Lorenz, Newman, 2002; Newman, Schmitt, & Voss, 1997; Sutton, Vitale, & Newman, 2002). Further, research suggests that the group high on anxiety (i.e., secondary psychopathy) shows higher levels of past child abuse and trauma in incarcerated adult samples (Blagov et al., 2011; Poythress et al., 2010).

Although variants of psychopathy have consistently differed on level of anxiety and histories of abuse and trauma, other hypothesized differences have not been as consistently supported in research. For example, some authors have suggested that the two groups may differ on the dimensions that form the construct of psychopathic traits. Specifically, the primary psychopathic group may be more likely to show CU traits, given the primacy of affective deficits attributed to this variant, whereas the secondary group may be more impulsive as result of problems in emotional regulation (Lykken, 1957; 1995). Research on adult samples largely have supported the prediction that the secondary variant shows higher rates of impulsivity but differences on the level of CU traits have not been consistently found (Blagov et al., 2011; Hicks, Markon, Patrick, Krueger, & Newman, 2004; Poythress et al., 2010; Vassileva, Kosson, Abramowitz, & Conrod, 2005). Similarly, several authors have suggested that, due to problems in emotional regulation, the secondary group would be more likely to show hostility and aggression, especially reactive forms of aggression in response to perceived provocation (Skeem et al., 2003). Again, research has found mixed results, with some studies supporting this prediction that the secondary group would be more aggressive (Falkenbach, Poythress, & Creevy, 2008; Hicks et al., 2004; Vidal, Skeem, & Camp, 2010) and others finding that the primary variant was more aggressive (Poythress et al., 2010).

One additional distinction that has important etiological implications is whether the two variants of psychopathy differ in the relative activation of neurophysiological motivational systems that influence behavior. For example, Gray (1987) proposed the presence of a behavioral inhibition system (BIS), which responds to aversive stimuli, is sensitive to punishment, and initiates avoidance. He further proposed a second system, the behavioral activation system (BAS), which responds to reward cues and activates approach responses (Gray, 1987). The activation of the BIS is associated with the production of anxiety and the BAS is associated with the behavioral trait of impulsivity or drive. Building upon this model, Lykken (1995) proposed that the primary psychopathy variant would be associated with a weak BIS (or fearless temperament and low anxiety), whereas secondary psychopathy would be associated with an overactive BAS (reward responsiveness and impulsivity). Again the available research in adult samples has been inconsistent, with results in incarcerated samples largely supporting this prediction (Newman, MacCoon, Vaughn, & Sadeh, 2005; Poythress et al, 2010; Wallace, Malterer, & Newman, 2009) but results in non-incarcerated samples failing to finding the expected differentiation in the two motivational systems among the variants of psychopathy (Hundt, Kimbrel, Mitchell, & Nelson-Gray, 2008; Falkenbach et al., 2008; Kimbrel, Nelson-Gray, & Mitchell, 2007; Ross et al., 2007).

Primary and Secondary Variants in Adolescent Samples

Given that the two variants of psychopathy both show high rates of CU traits in adult samples, this research could be critical for understanding antisocial youth who show high levels of these traits and, as a result, it is relevant to the proposed changes to the diagnostic criteria of Conduct Disorder. Although the research on variants of psychopathy prior to adulthood has been more limited, there have been promising findings on samples of adolescent offenders. Like in adult samples, a subset of adolescent offenders who are high on psychopathy are also high on anxiety (Kimonis, Frick, Cauffman, Goldweber, & Skeem, 2012; Lee, Salekin, & Iselin, 2010). Also consistent with adult samples, the two variants do not differ on their level of CU traits, but the group high on anxiety is more impulsive (Kimonis et al., 2012). Further, this secondary group shows greater histories of childhood abuse and trauma (Kimonis, Skeem, Cauffman, & Dmitrieva, 2011; Tatar, Cauffman, Kimonis, & Skeem, 2012; Vaughn, Edens, Howard, & Smith, 2009). They also show more problems with depression, anger, and aggression (Kimonis et al., 2012; Kimonis et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2010; Vaughn et al., 2009). Further, and also consistent with the research on adults, the low anxiety group (i.e., primary psychopathy) shows deficits in their processing of emotional stimuli that are not apparent in the secondary group (Kimonis et al., 2012).

Limitations in Existing Research

Taken together, this research could have important implications for understanding the causal pathways that can lead to CU traits and suggest the need for different treatment approaches to the two variants of youths with CU traits (Kimonis et al., 2012). However, in addition to the relatively limited number of studies on samples of youths (Lee et al., 2010), there are several limitations to the existing research. Most importantly, to date, all of the studies on variants of psychopathy in youths have been conducted in offender samples. This methodology is often justified by the need to have a high base rate of persons elevated on psychopathic traits in order to identify sufficient numbers of both variants to test hypothesized differences. However, it calls into question the generalizability of these results to other samples that do not have legal involvement. In particular, given the potential inclusion of the specifier for the diagnosis of Conduct Disorder, the generalizability of these findings to mental health samples in which a large number of youths with this disorder could meet criteria for the specifier needs to be tested. Further, although the proposed changes to the DSM-5 only would consider CU traits when the criteria for Conduct Disorder are met, there is evidence that CU traits even in absence of Conduct Disorder predicts risk for future impairment in functioning in children and adolescents (Moran et al. 2009).

It is also important that these results be replicated in samples with a large number of ethnic minority individuals and in low-income samples. With respect to the former, there have been concerns raised as to the validity of psychopathic traits in general, and CU traits in particular, in ethnic minority samples (Edens & Cahill, 2007). Further, the rates of abuse and trauma may be particularly high in low-income samples (Berger, 2005). As a result, the secondary variant of psychopathy, which tends to be the smaller subgroup of those high on psychopathic traits in most forensic samples of youths (Kimonis et al., 2012), may be more common in impoverished samples with high levels of life stressors. Thus, it is important to ensure that the findings from incarcerated samples generalize to other samples of high-risk youths.

Further, as noted previously, an important area of research that has shown inconsistent results in samples of adults is the differential associations between the motivational systems that may underlie disinhibited behavior and the variants of psychopathy. This has been tested in two community samples of adolescents, with again, inconsistent results. In one study of at-risk adolescents, the BIS was lower in those who showed primary psychopathy, as would be predicted by past theoretical models; but both primary and secondary variants demonstrated higher BAS scores (Bjørnebekk & Gjesme, 2009). In contrast, in a large sample of Dutch adolescents, results were consistent with past theoretical models (Roose, Bijttebier, Claes, & Lilienfeld, 2011). Thus, more work is needed to test the characteristics of the two psychopathy variants in terms of their motivational style, and this is particularly important to test in non-forensic samples, given the findings in adults suggesting that the predicted pattern (i.e., low BIS associated with primary variants and high BAS associated with secondary variants) has not been replicated in non-incarcerated samples.

Finally, most of the past studies comparing variants of psychopathy in both adults and adolescents have relied primarily on information obtained by self-report methods. It is possible that this methodology could have led to some of the inconsistent findings in past research. Specifically, it has been suggested that persons with psychopathy in general (Edens, Buffington, & Tomicic, 2000; Kucharski, Duncan, Egan, & Falkenbach, 2006), and those with the primary variant of psychopathy specifically (Cleckley, 1941; 1976), may be less truthful on self-report measures because of their tendency toward being manipulative and deceitful. As a result, it is important for research to compare results from multiple informants to compare characteristics of the different variants of CU traits across informants. Also, research to date has not directly tested the credibility of the information provided by participants with CU traits. If these traits are to be integrated into diagnostic classification, these issues related to method of assessment become more imperative.

Current Study

Based on these limitations in existing research we tested whether we could identify primary and secondary variants of CU traits in a large sample of clinic-referred adolescents who were largely African-American and from impoverished family backgrounds. Using model-based cluster analyses with measures of CU traits, anxiety, and trauma symptoms, we hypothesized that three clusters would emerge: one cluster low on CU traits and two clusters equally high on CU traits that would be differentiated by levels of anxiety and trauma symptoms. We chose to use a measure of CU traits specifically, rather than a broader measure of psychopathy more generally, because we wanted our findings to be directly relevant to understanding adolescents high on these traits, as proposed in the specifier for Conduct Disorder. However, as noted previously, given that past research has consistently shown that both variants of psychopathy are high on these traits, we believe our results would be relevant to understanding the broader construct of psychopathy.

Consistent with past work, we predicted that the secondary cluster would be high on anxiety and trauma symptoms, would demonstrate more extensive histories of abuse, score higher on measures of impulsivity, and demonstrate more aggressive behavior and externalizing symptoms than the primary variant or than a cluster low on CU traits. Importantly, we differentiated a more general measure of aggression from one that focused more on cruelty to others, to test whether the secondary variants higher level of aggression was confined to more reactive and impulsive forms of aggression. Further, we tested the hypothesis that primary variants would be distinguished from secondary variants by showing significantly lower BIS scores, whereas the secondary variants would be distinguished from primary variants by showing significantly higher BAS scores. Finally, we used measures from multiple informants for most constructs, which allowed us to compare characteristics of the different variants of CU traits across informants. Furthermore, we included global clinician ratings of credibility of the information provided by participants to determine if clinicians would view persons with CU traits differently in terms of the believability of their self-report.

Method

Participants

Participants were drawn from 300 adolescents (ages 11 to 18; M = 13.40, SD = 1.85) recruited as part of a larger study from a community mental health center (CMHC) serving four urban sites in the Midwestern United States. Families were recruited from all intakes and 65% agreed to participate. Consistent with the typical rate of first appointments at these CMHC, 59% kept their first appointment. Participants were excluded from the present analyses if they had a diagnosis for a Psychotic Disorder (2%, n = 7) or a Pervasive Developmental Disorder (1%, n = 3) based on a structured diagnostic interview, or if they had missing or incomplete data (6%, n = 18) on the clustering variables. This led to a final sample of 272 with a mean age of 13.43 (SD = 1.86) years. The primary ethnic category was African American (90%, n = 246) and the next most common was Caucasian (6%, n = 16), and 51% (n = 139) of the sample was male. In terms of SES, approximately 95% of the participants were Medicaid eligible, representative of the counties served by the CMHC. The only inclusionary criterion for the current study was the patient needed to be between the ages of 11 and 18, and the patient and caregiver needed to be conversant in spoken English in order to complete the interviews. The Child & Adolescent Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia – Present and Lifetime version (K-SADS; Kaufman et al., 1997) including the mood disorders module from the Washington University version (Geller et al., 2001) was given to all participants. Based on this semi-structured interview, the most common diagnoses of the sample were Mood Disorders (53%, n = 144), Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (53%, n = 145), followed by Oppositional Defiant Disorder (35%, n = 95) and an Anxiety disorder (32%, n = 87). Additionally, 18% (n = 48) of the sample had a diagnosis of Conduct Disorder and 11% (n = 30) met criteria for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. The majority of participants had more than one diagnosis (80%, n = 220) and the average number of diagnoses per participant was 2.72 (SD = 1.40). Only two participants did not meet criteria for any diagnostic category.

Measures

Callous-Unemotional Traits and Impulsivity

The Antisocial Process Screening Device (APSD; Frick & Hare, 2001) is a 20-item rating scale that is commonly used to assess CU traits in children and adolescents (Frick, 2009). This measure has a three factor structure (Frick, Bodin, & Barry, 2000) that includes Callous Unemotional Traits, Narcissism, and Impulsivity. Only the Callous Unemotional (CU) (e.g. “feels bad or guilty”, “does not show emotions”) and Impulsivity (e.g. “acts without thinking”, “engages in risky activities”) factor scores were used for the current study. On the APSD, items are scored on a 3-point scale ranging from 0 (“not at all true”) to 2 (“definitely true”). The APSD was administered to all parents and youth. For the cluster analyses, a combined-informant composite score was formed for CU traits based on the highest rating of each symptom as recommended by Piacentini, Cohen, and Cohen (1992) and Frick and Hare (2001). If an informant was missing, the ratings of the available informant were used. For the six-item CU scale, internal consistency within our sample was α = .40, α = .59, α = .51 for the self, parent, and multi-informant versions, respectively. The parent and youth versions were modestly correlated (r = .15, p < .05). While the alpha coefficients were modest for this scale, short scales can have attenuated internal consistency estimates. Thus, an alternative measure of reliability recommended for shorter scales is the median corrected item-total correlation (Streiner & Norman, 1995) and this was r = .32, r = .36; and r = .32 for the self, parent, and multi-informant composites, respectively. For the self and parent report of the seven-item Impulsivity subscale, the internal consistency estimates were α = .60 and α = .70, respectively, and the two scores were modestly correlated (r = .17, p < .01).

Child Trauma and PTSD Symptoms

The Child and Adolescent Trauma Survey (CATS; March, 1999) formerly known as the Kiddie Post-Traumatic Symptomatology Scale (K-PTS) is a self-report assessment of PTSD symptoms derived from DSM-IV criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). The CATS is modeled after the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC; March, 1998; March, Parker, Sullivan, Stallings, & Conners, 1997) and is a unique self-report instrument, as it assesses both exposure to trauma and PTSD symptom criteria. A non-PTSD life events section consists of stressful life events and includes items such as “my mother and father got in trouble with the law” or “I got suspended from school.” The trauma exposure section assesses both direct (happened to me) and indirect (happened to someone I know well) lifetime experience of traumatic events. For the PTSD symptom section, participants are asked to rate how often they have experienced the symptoms in the past month on a four-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (“Never”) to 3 (“Often”). The scale contains two questions that correspond to each individual DSM-IV PTSD symptom. Both the non-PTSD life events and trauma exposure list were summed to create an overall Stressful/Traumatic exposure list, and a separate PTSD symptom inventory was individually summed to produce a total symptom count. The CATS was developed using item-response theory and the items have demonstrated good internal reliability (March, Amaya-Jackson, Terry, & Costanzo, 1997) as well as good test-retest reliability (March, Amaya-Jackson, Murray, Shulte, 1998). Internal consistency in our sample was α = .84 for the trauma exposure and α = .84 for the PTSD symptom scale.

Child Neglect and Abuse

History of physical abuse, sexual abuse, or neglect was determined by combining information from multiple sources including questions on the K-SADS, a review of the medical records, and official social service records from the treatment charts at the CMHC agency. All sources of information were used to make a dichotomous rating of the presence or absence of each type of abuse. Kappas for abuse history were calculated testing the level of agreement between the interview of the caregiver (K-SADS) and review of the records on the presence of each abuse type. They ranged from .71 for physical abuse to .83 for sexual abuse. Any discrepancies between sources were resolved through a consensus meeting where all available data was reviewed and the final determination of a positive or negative history of abuse was made by a licensed clinical psychologist. This final consensus rating was used in all analyses.

Emotional and Behavioral Functioning

Parents completed the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) and youth completed the analogous Youth Self Report (YSR; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2003). These standardized behavior rating scales assess for emotional and behavioral problems in children and adolescents using a three-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (“not true”) to 2 (“very true”). The well validated Externalizing composite and Anxious-Depressed composites were used in the cluster analyses. Internal consistency for the Externalizing composite was α = .90 and α = .93 for self and parent report respectively, and the two scores were significantly correlated (r = .34, p < .001). Internal consistency for the Anxious-Depressed composite was α = .82 and α = .81 for self and parent report respectively, and the two scores were significantly correlated (r = .27, p < .001).

Given that the standard Aggressive Behavior scale of the CBCL and YSR includes a number of non-aggressive conduct problems (e.g., demands a lot of attention, sudden changes in mood or feelings, sulks a lot), a physical aggression scale was formed for the parent report CBCL (α = .78) by summing three items specific to physical aggression (i.e., gets in many fights, physically attacks people, threatens people). An additional cruelty subscale was formed by summing two items related to cruel behavior (i.e., cruelty to animals; cruelty, bullying, or meanness to others; r = .33). A physical aggression scale was also formed for the self-report YSR (α = .92). One item on the self-report measure assesses cruelty, (mean to others) and the original three-point Likert-type rating for this item was used in analyses. The physical aggression totals for self and parent report were highly correlated (r = .39, p < .001) and the cruelty scale totals for self and parent report were modestly correlated (r = .13, p < .05).

Behavioral Inhibition and Activation

Youth self-report and parent-report versions of the Carver and White (1994) Behavioral Inhibition Scale and Behavioral Activation Scales (BIS/BAS; Muris, Meesters, Kanter, & Timmerman, 2005) assessed degree of behavioral inhibition and activation. The scale consists of 20 items rated on a four-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (“not true”) to 3 (“very true”). The BIS scale consists of 7 items and includes statements such as “I worry about making mistakes” and “I am very fearful compared to my friends.” The BAS scale is composed of 13 items and consists of statements such as, “I often do things on the spur of the moment” and “I will go out of the way to get things I want”. Within community samples of children, BIS/BAS scores have demonstrated associations with both self-reported psychological symptoms and personality traits (Bjørnebekk, 2009; Muris et al., 2005). For example, in a sample of children aged 8 to 12, BIS scores were negatively associated with Eysenck’s Extraversion trait, positively associated with Neuroticism, and related to higher levels of internalizing symptoms (Muris et al., 2005). In contrast, BAS scores were positively associated with Extraversion, positively associated with Neuroticism, and related to higher levels of externalizing symptoms (Muris et al., 2005). In the present sample, internal consistency for the BIS was α = .68 and α = .58 for the youth and parent report, respectively, and the two scores were not significantly correlated (r = .04, p = .49). For the BAS scale, internal consistency was α = .78 and α = .84 for youth and parent report respectively, and the two scores were not significantly correlated (r = .08, p = .20).

Credibility Ratings

Interviewers provided global subjective ratings of parent and youth credibility after completion of the K-SADS. These ratings were based solely on the clinical judgment of the interviewer without any specialized training provided. In particular, interviewers judged how credible they perceived the information obtained from parent and youth during interviews. Ratings of informant credibility were given on a 3 point Likert scale ranging from 0 (“poor”) to 2 (“good”) (Youngstrom et al., 2011). Credibility ratings were made blind to any of the other study measures. Interviewers were bachelors, masters, or predoctoral intern level psychology trainees who had completed extensive training in the administration of the interviews, including observation and re-rating of at least five diagnostic interviews with an average kappa greater than .85 at the item level, and then leading and passing at kappa >.85 when a certified reliable rater watched and independently scored the interview. Further, these credibility ratings have been shown to be related to the validity of parent ratings of mood and behavioral symptoms in youth (Youngstrom et al., 2011).

Procedure

This study was conducted as part of a larger research project approved by the Institutional Review Boards of University Hospitals of Cleveland, Case Western Reserve University, and Applewood Centers, Incorporated. For all participants, the youth provided written assent and the guardian provided written consent. The interviewer met with the adolescent and parent separately and, while the youth was being interviewed, the parents completed questionnaires. While the parent was completing interviews, adolescents were given self-report questionnaires.

Results

Cluster Analyses

Cluster Selection

Using SPSS 19, the two-step cluster analysis procedure was performed in order to classify the participants on the following four variables: the combined parent and youth report on the CU factor scale from the APSD (Frick & Hare, 2001), the Anxious-Depressed Scale (ANX-DEP) from the YSR (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2003), and trauma exposure and PTSD symptom scores from the CATS (March et al., 1999). These informants were chosen to utilize the best informants for the different constructs assessed in order to form groups. Specifically, assessment of antisocial attitudes in general, and CU traits specifically, typically are best assessed by multiple informants, since parents may not be aware of some attitudes and feelings and self-report can be subject to social desirability in reporting (Frick, Barry, & Kamphaus, 2010). In contrast, internalizing symptoms are characterized by internal emotional states that may not be apparent to parents and are typically best assessed by self-report after early childhood (Frick et al., 2010).

The two-step method is an auto-cluster procedure that combines both Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC) and ratio of distance between clusters in order to determine the optimal number of clusters (SPSS, 2004). The clustering procedure consists of two steps and is based on a probabilistic model where the distance between clusters is parallel to the decrease in log-likelihood function, which is a result of merging nearest neighbors (Chiu, Fang, Chen, Wang, & Jeris, 2001). For the first step, pre-clusters are formed based on a sequential approach. A likelihood distance measure is used to determine each case’s similarity to an existing pre-cluster and pre-clusters are formed when the log-likelihood is maximized. The second step uses a model based hierarchical technique, similar to agglomerative hierarchical techniques. The optimal number of clusters is determined by the statistical program by weighing both the ratio of distance between clusters and the change in BIC (Bacher, Wenzig, & Vogler, 2004).

Based on past research, it was theorized that there would be a cluster of youth low on CU traits along with two clusters high on CU traits that would be differentiated by different levels of anxiety and trauma exposure. The results of the cluster analyses were consistent with this theoretical prediction. The three cluster solution was selected by the two step procedure as providing the best fit. The BIC change between the two and three cluster solution was 43.29 and this was combined with ratio of distance measure of 1.54. The algorithm judged this to be superior to a four cluster solution, which had a BIC change of 12.24 from the three cluster solution and ratio of distance measure of 1.08.

Description of Clusters

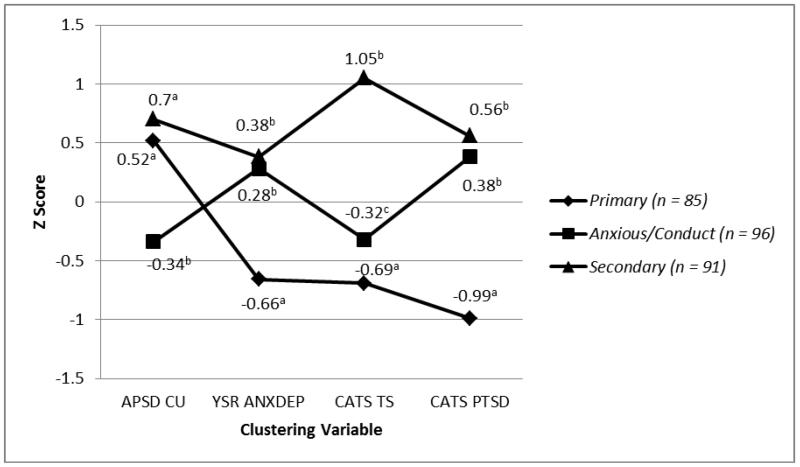

There were no significant differences between clusters on age, gender, or race of the participant. Figure 1 plots the profiles of the clustering variables for all three clusters using the standardized scores (z-scores) for the clustering variables. The overall ANOVAs were significant for all four clustering variables (ηp2 ranging from .21 to .56). Pairwise comparisons determined what clusters differed from each other. The first cluster (n = 85) was labeled “primary” because it showed significantly higher scores on the CU factor (M = 7.74, SD = 1.78) than the third cluster (M = 5.75, SD = 1.54) but did not differ significantly from the second cluster (M = 8.18, SD = 1.98). This cluster also had significantly lower scores on the ANX-DEP (M = 51.61, SD = 2.80), CATS trauma exposure (M = 5.34, SD = 3.05), and PTSD symptoms (M = 3.73, SD = 4.07) than both of the other clusters. The second cluster (n = 91) labeled “secondary” scored higher on the CU factor than the third cluster and had significantly higher scores on the ANX-DEP scale (M = 60.47, SD = 10.25) than the primary cluster. This cluster also had significantly higher scores on the CATS trauma exposure (M = 16.57, SD = 5.97) than the other clusters (and significantly higher scores on the PTSD symptoms scale (M = 17.32, SD = 7.91) than the primary cluster). These results held when re-running analyses excluding abuse items from the CATS trauma scale. Further, when differentiating between direct and indirect forms of trauma exposure on the CATS trauma scale, the overall ANOVAs were significant for both direct (F (2, 269) = 42.36, p < .001, ηp2 = .240) and indirect (F (2, 269) = 80.13, p <. 001, ηp2 = .373) forms of trauma. Post hoc pairwise comparisons revealed that the secondary cluster had significantly higher scores on both direct (M = 2.46, SD = 2.36) and indirect (M = 6.80, SD = 4.43) forms of trauma than the primary (direct: M = 0.46, SD = 0.73; indirect: M = 1.32, SD = 2.09) and third (direct: M = 0.91, SD = 0.92; indirect: M = 2.22, SD = 2.24) clusters. Importantly, the secondary cluster did not differ significantly from the primary cluster on the CU factor.

Figure 1.

Cluster variable z score profiles for three emergent clusters.

Rates with different superscripts differ significantly across groups in pairwise comparisons. APSD CU = Antisocial Processing Screening Device Callous Unemotional Score; YSR ANXDEP = Youth Self-Report Anxious/Depressed Score; CATS TS = Child and Adolescent Trauma Survey Trauma Symptom Total; CATS PTSD = Child and Adolescent Trauma Survey Post Traumatic Stress Disorder Symptom Total.

Finally, the third cluster (n = 96) had significantly lower scores on the CU factor than both the primary and secondary clusters. We labeled this group “anxious-conduct” due to relatively high rates of self and parent-reports of anxiety-depression and on externalizing behaviors. On exposure to trauma, the anxious-conduct cluster had significantly lower scores (M = 7.76, SD = 3.09) than the secondary but significantly higher scores than the primary cluster. The anxious-conduct cluster also demonstrated significantly higher scores on the PTSD symptom scale (M = 15.68, SD = 6.53) than the primary cluster, but did not differ significantly from the secondary cluster on this scale.

Effects of Informants on Clustering Variables

The clusters were formed using what would be considered optimal informants for assessing the constructs used in the cluster analyses; namely, combining parent and youth report for CU traits and using youth self-report for the assessment of anxiety and trauma. We examined the clusters to see whether the differences across clusters were consistent across various informants. Table 1 also reports the results of these analyses. As was the case when using the combined report of parent and youths, the three clusters differed significantly when using the parent (F (2, 264) = 23.25, p < .001, ηp2 = .150) and youth reports (F (2, 262) = 14.24, p < .001; ηp2 = .098) of CU traits, separately. Further, pairwise comparisons indicated that both the primary (youth: M = 4.56, SD = 2.00; parent: M = 6.19, SD = 2.34) and secondary variants (youth: M = 5.28, SD = 2.05; parent: M = 6.33, SD = 2.30) had higher rates of CU traits than the anxious-conduct cluster (youth: M = 3.74, SD = 1.76; parent: M = 4.43, SD = 1.62) for both informants. However, whereas the secondary group self-reported high rates of CU traits when compared to the primary group, the two groups did not differ based on parent report.

Table 1. Test of Informant Differences on Clustering Variables and Cluster Differences on Rates of Abuse.

| Primary | Secondary | Anxious- Conduct |

Test Statistic | Effect Size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CU Traits | |||||

| Youth APSD |

(n = 84) 4.56 (2.00)a |

(n = 89) 5.28 (2.05)b |

(n = 92) 3.74 (1.76)c |

F (2, 262) = 14.24*** | ηp2 =.098 |

| Parent APSD |

(n = 84) 6.19 (2.34)a |

(n = 89) 6.33 (2.30)a |

(n = 94) 4.43 (1.62)b |

F (2, 264) = 23.25*** | ηp2 =.150 |

| Anxious Depressed | |||||

| Youth YSR |

(n = 85) 51.61 (2.80)a |

(n = 91) 60.47 (10.25)b |

(n = 96) 59.68 (7.54)b |

F (2, 269) = 36.48*** | ηp2 =.213 |

| Parent CBCL |

(n = 83) 60.39 (9.04)a |

(n = 89) 64.48 (9.71)b |

(n = 94) 62.67 (9.90)ab |

F (2, 263) = 3.83* | ηp2 =.028 |

| Abuse | (n = 85) | (n = 91) | (n = 96) | ||

| Physical | 14 (17%)a | 27 (31%)b | 15 (16%)a | χ2 (2) = 7.35* | φ =.17 |

| Sexual | 15 (18%)a | 30 (36%)b | 15 (16%)a | χ2 (2) = 11.41** | φ =.21 |

| Neglect | 14 (17%) | 19 (23%) | 17 (18%) | χ2 (2) = 1.01 | φ =.06 |

Note.

= p < .001

= p < .01

= p < .05, two tailed. Rates with different superscripts differ significantly in pairwise comparisons. APSD = Antisocial Process Screening Device; CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist; YSR = Youth Self Report.

As also reported in Table 1, there were few differences in informant reports on the ANX-DEP subscales of CBCL and YSR. Specifically, for both parent (M = 64.48, SD = 9.71) and youth (M = 60.47, SD = 10.25) report, the secondary group showed significantly higher levels of anxiety than the primary group (youth: M = 51.61, SD = 2.80; parent: M = 60.39, SD = 9.04). Similarly, when the three clusters were compared on their history of physical abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect based on direct interview combined with review of records (Table 2), the three clusters differed significantly on rates of physical abuse (χ2(2) =7.35, p < .05, φ = .17) and sexual abuse (χ2(2) =11.41, p < .01, φ = .21). Follow-up pairwise analyses indicated that, consistent with hypotheses and consistent with results of the cluster analyses using self-report of trauma, the secondary cluster had significantly higher rates of physical (31%) and sexual abuse (36%) than the primary cluster (physical: 17%; sexual: 18%) and the anxious-conduct cluster (physical: 16%; sexual: 16%). No significant differences on rates of neglect were present across clusters.

Table 2. Cluster Differences on Impulsivity, Aggression and Cruelty, Externalizing Behavior, and Behavioral Inhibition/Activation.

| Primary | Secondary | Anxious-Conduct | Test Statistic | η p 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impulsivity | |||||

| Youth APSD |

(n=85) 4.00 (1.98)a |

(n=90) 5.18 (1.97)b |

(n=96) 4.65 (1.90)b |

F (2, 268) = 7.99*** | .056 |

| Parent APSD |

(n=85) 5.76 (2.17)ab |

(n=91) 6.17 (2.65)a |

(n=88) 5.21 (2.11)b |

F (2, 261) = 3.89* | .029 |

| Externalizing | |||||

| Youth YSR |

(n = 85) 52.65 (11.02)a |

(n = 91) 64.63 (11.28)b |

(n = 96) 58.77 (9.01)c |

F (2, 272) = 28.89*** | .180 |

| Parent CBCL |

(n = 83) 69.65 (9.07)a |

(n = 89) 72.37 (9.35)a |

(n = 94) 66.01 (9.86)b |

F (2, 266) = 10.45*** | .074 |

| Aggression | |||||

| Youth YSR |

(n = 83) 0.90 (1.18)a |

(n = 88) 2.07 (1.82)b |

(n = 93) 0.98 (1.33)a |

F (2, 261) = 17.03*** | .115 |

| Parent CBCL |

(n = 82) 2.22 (1.93)a |

(n = 86) 2.90 (1.92)b |

(n = 92) 1.71 (1.95)a |

F (2, 260) = 8.27*** | .060 |

| Cruelty | |||||

| Youth YSR |

(n = 85) 0.44 (0.63)a |

(n = 89) 0.85 (0.70)b |

(n = 95) 0.62 (0.62)a |

F (2, 266) = 9.08*** | .064 |

| Parent CBCL |

(n = 83) 1.12 (1.05)a |

(n = 88) 1.27 (1.07)a |

(n = 94) 0.75 (0.97)b |

F (2, 262) = 6.36** | .046 |

| BIS | |||||

| Youth |

(n = 82) 19.32 (5.61)a |

(n = 88) 21.74 (4.29)b |

(n =95) 21.53 (4.44)b |

F (2, 265) = 6.65** | .048 |

| Parent |

(n = 83) 20.40 (4.45) |

(n = 86) 21.29 (4.58) |

(n = 93) 21.22 (3.86) |

F (2, 259) = 1.13 | .009 |

| BAS | |||||

| Youth |

(n = 79) 32.61 (5.95)a |

(n =89) 35.10 (7.00)b |

(n = 93) 34.71 (7.00)ab |

F (2. 261) = 3.25* | .025 |

| Parent |

(n = 82) 34.07 (6.92)a |

(n = 84) 36.99 (7.76)b |

(n = 88) 35.16 (6.58)ab |

F (2, 251) = 3.59* | .028 |

Note.

= p < .001

= p < .01

= p < .05, two-tailed. Rates with different superscripts differ significantly in pairwise comparisons. APSD = Antisocial Process Screening Device; BIS = Behavior Inhibition Scale; BAS = Behavior Activation Scale; CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist; YSR = Youth Self Report.

External Validation

Impulsivity

Using the three clusters, an ANOVA tested the Impulsivity scale from the APSD (both parent and self-report version) as the dependent variable (Table 2). For self and parent report, the overall ANOVAs were significant (F (2, 268) = 7.99, p < .001, ηp2 =. 056; (F (2, 261) = 3.89, p < .05, ηp2 = .029). Post hoc pairwise comparisons revealed that the results for self-report were as predicted. The secondary cluster (M = 5.18, SD = 1.97) scored significantly higher on impulsivity than the primary cluster (M = 4.00, SD = 1.98), while the primary cluster scored lower on impulsivity than the Anxious-Conduct cluster (M = 4.65, SD = 1.90). For parent report, however, the secondary cluster (M = 6.17, SD = 2.65) had significantly higher levels of impulsivity than the Anxious-Conduct cluster (M = 5.21, SD = 2.11) but the two groups high on CU traits did not differ.

Externalizing, Aggression & Cruelty

Next, a series of ANOVAs tested potential differences between clusters using the Externalizing composites from the CBCL and YSR and the aggressive behavior and cruelty scales formed for this study. As noted in Table 2, the overall ANOVAs were significant (ηp2 ranging from .05 to .18). Post hoc pairwise comparisons also revealed significant group differences among groups. For the physical aggression scale, the results were consistent with hypotheses and consistent across informants. That is, the secondary cluster (youth: M = 2.07, SD = 1.82; parent: M = 2.90, SD = 1.92) showed higher levels of aggression than the primary cluster (youth: M = 0.90, SD = 1.18; parent: M = 2.22, SD = 1.93) and anxious-conduct cluster (youth: M = 0.98, SD = 1.33; parent: M = 1.71, SD = 1.95). However, for externalizing and cruelty, the results were not consistent across informants. For self-report, the secondary cluster (externalizing: M = 64.63, SD = 11.28; cruelty: M = 0.85, SD = 0.70) scored higher than the primary cluster (externalizing: M = 52.65, SD = 11.02; cruelty: M = 0.44, SD = 0.63) but the two clusters high on CU traits did not differ according to parent report.

Behavioral Inhibition and Activation

The next set of ANOVA analyses used the BIS and BAS self and parent-report scores as dependent variables (see Table 2). For all but the parent report on the BIS scale (F (2, 259) = 1.13, p=.33, ηp2 =. 009) the overall ANOVAs were significant (BIS youth: F (2, 265) = 6.65, p < .01, ηp2 = .048; BAS parent: (F (2, 251) = 3.59, p < .05, ηp2 = .028; BAS youth: (F (2, 261) = 3.25, p < .05, ηp2 = .025). Post hoc pairwise comparisons for the BAS were consistent with predictions and were consistent across informants. Specifically, the secondary cluster showed higher BAS scores than the primary cluster for both self-report (secondary: M = 35.10, SD = 7.00; primary: M = 32.61, SD = 5.95) and parent report (secondary: M = 36.99, SD = 7.76; primary: M = 34.07, SD = 6.92). For the BIS, the results were consistent with predictions for self-report, with the primary cluster (M = 19.32, SD = 5.61) showing lower scores on the BIS than the secondary cluster (M = 21.74, SD = 4.29). However, there were no significant differences across clusters for the parent report version of the BIS.

Credibility Ratings

Using chi-square analyses, the three clusters were compared on credibility ratings of parents and youth made by clinicians blind to the responses on the rating scales that defined cluster membership. The three clusters differed significantly on perceived youth credibility (χ2(4) =15.54, p < .001, φ = .29) but not perceived parent credibility (χ2(4) =5.88, p = .21). Follow-up pairwise chi-square analyses examined differences between clusters on the ratings of the youths’ credibility. The primary cluster was significantly more likely to receive a rating of poor credibility (25%) than the secondary cluster (11%; (χ2(2) = 6.34, p < .05, φ = .21) and anxious-conduct cluster (11%; (χ2(2) =15.42, p < .001, φ = .33).1

Discussion

The current study examined whether clinically referred adolescents with CU traits can be disaggregated into two distinct groups, consistent with past research on primary and secondary variants of psychopathy conducted in samples of incarcerated adults (Skeem et al., 2003) and juvenile justice-involved youths (Lee et al., 2010). Using model based cluster analyses, we found two distinct groups of youths high on CU traits that differed as predicted on anxiety and past trauma. Specifically, a primary variant emerged with high levels of CU traits and low levels of anxiety, trauma, and PTSD symptoms. A secondary variant also emerged with high levels of CU traits accompanied by high levels of self-reported anxiety, trauma and PTSD symptoms.

Consistent with past causal theories for the secondary variant (Karpman, 1941, 1948; Skeem et al., 2003), the secondary variant had significantly higher levels of physical and sexual abuse. Also consistent with theories predicting that this group would have more problems with impulse control and emotional regulation (Lee et al., 2010; Lykken, 1995; Skeem et al., 2003), the secondary variant scored higher on measures of impulsivity, externalizing behaviors, and aggression. Finally, although the findings from past research have been inconsistent, our results support Lykken’s (1995) theoretical view that lower levels of behavioral inhibition would characterize the primary variant, whereas the secondary cluster would show higher scores on the behavioral activation system.

These findings, combined with similar results from incarcerated samples of adolescents (Kimonis et al., 2012; Kimonis et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2010; Tatar et al., 2012; Vaughn et al., 2009), suggest that causal models proposed to explain the development of CU traits need to consider these two variants with very different characteristics. Further, these differing characteristics are consistent with theories suggesting that CU traits in the primary variant are a result of an emotional deficit related to low behavioral inhibition that can interfere with the development of empathy, guilt, and other aspects of conscience (Kimonis et al., 2012). In contrast, the secondary variant appears to have problems in emotional and behavioral regulation that could be a result of experiencing abuse and other trauma early in development (Kimonis et al., 2012). Importantly, this secondary variant was the most common group high on CU traits in this sample, which is different from findings in incarcerated samples. For example, in the current sample, 52% of those high on CU traits fell into the secondary cluster, compared to 26% of those high on CU traits in a sample of incarcerated adolescents (Kimonis et al., 2012). These findings suggest that in a low-income sample with high rates of trauma, this variant may be a common pathway to the development of high levels of CU traits.

One important factor for interpreting our results was a clear pattern of informant effects that could help to explain some of the inconsistent findings from past research and which have important implications for assessing these traits. Specifically, much of the past work on variants of CU traits in samples of youths has relied on self-report (Bjørnebekk & Gjesme, 2009; Kimonis et al., 2012; Roose et al., 2011; Tatar et al., 2012; Vaughn et al., 2009). Some of the differences between the two variants in the current study were significant only when self-report measures were used. Specifically, the primary and secondary clusters differed on their levels of impulsivity, externalizing behaviors and behavioral inhibition by self-report only. Parent report failed to confirm these differences. Importantly, all group differences between the clusters high on CU traits cannot be attributed to informant effects, because the secondary variant showed higher levels of abuse by an approach that integrated direct semi-structured interview with review of records, and the secondary group showed higher rates of anxiety, aggression, and behavioral activation according to both parent and self-report. However, it does appear that youths in the primary cluster tend to underreport the level of their behavioral disturbance, relative to what is reported by parents.

It is not clear what might lead to this underreporting by youths in the primary cluster. Past research has consistently documented modest agreement between parent report and youth report of children’s emotional and behavioral problems and this finding has often been explained by differences in perspectives across informants and/or different attributions of the informants for the causes of the behaviors and emotions (Achenbach, McConaughy, & Howell, 1987; De Los Reyes & Kazdin, 2005) However, this does not specifically explain the consistent direction of disagreement found in the current results in which youth in the primary cluster were more likely to report less problems then their parent nor does it explain why this same effect was not apparent in the secondary cluster. One possibility is that the primary group may be more likely to minimize their behavioral difficulties, either due to intentional deception and manipulation (Cleckley, 1942; 1976; Edens et al., 2000; Kucharski et al., 2006) or because of their lack of concern about the effects of their behavior on others (Pardini, Lochman, & Frick, 2003). Consistent with the former possibility, subjective ratings of credibility of parent and youth reports revealed that clinicians were significantly more likely to rate credibility as poor for the youth in the primary cluster compared to the secondary or anxious-conduct clusters. At the same time, clinicians’ subjective ratings of parent credibility did not differ across clusters. This and other reasons for this informant effect need to be tested in future research and could be important for the assessment of this group in both research and clinical settings. Specifically, such informant effects may help to explain some of the inconsistencies in findings from past research on characteristics of the primary and secondary variants of psychopathy, given that much past research has relied on self-report. Also, these findings suggest that assessments of these traits should include multiple informants and not solely rely on self-report.

Several limitations qualify these results. One limitation is the relative homogeneity of our sample with regards to ethnicity. Though we tested, and found no differences between clusters on race, our sample was primarily African American (90%), and this may limit the generalizability of our findings to other ethnicities. Another limitation in our measures is the low internal consistency of some of our scales, especially our measures of CU traits, impulsivity, and parent report BIS. This is likely due to the small number of items on these scales (Nunnally, 1978; Streiner & Norman, 1995). However, this could have attenuated our ability to detect differences across groups. Additionally, credibility ratings were based on subjective clinician judgment at the end of a diagnostic interview and no inter-rater reliability estimates were available for these ratings. Further, we separated items related to general physical aggression from items related to cruelty, with the latter used to assess more proactive forms of aggression. However, these measures had very few items and a more extensive measurement of the different forms of aggression may have led to clearer differences on the types of aggression.

Importantly, the current study examined distinct subtypes of CU traits in a sample of clinic-referred youth, complementing and extending past research that has largely focused on incarcerated samples. However, it is important that future research test the importance of the variants of CU traits in other samples of youth, including inpatient and community samples. Further, the current study was cross-sectional in design, which precludes causal statements. In considering the secondary variant for example, while it is possible that exposure to trauma or abuse may lead to the development of CU traits, it is also possible that the existence of CU traits in these youth increases the likelihood that they will be exposed to contexts involving trauma and abuse. Finally, the current study tested variants of CU traits, irrespective of the presence of Conduct Disorder, which is not consistent with the proposed specifier for this diagnosis (Frick & Nigg, 2012). As noted previously, those elevated on CU traits seem to show clinically significant impairments, even in the absence of a diagnosis of Conduct Disorder (Moran et al., 2009). As a result, they represent a clinically important group. Further, there is no evidence to suggest that the etiology of CU traits is different in those with and without CD (Rutter, 2012).

Within the context of these limitations, our results demonstrate that within youth high on CU traits, there seem to be two distinct variants that differ on their levels of anxiety, history of abuse, impulse control, and emotional regulation. As suggested by us and past authors (Kimonis et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2010; Skeem et al., 2003), these characteristics seem to suggest distinct etiological pathways for the two groups high on CU traits. Furthermore, these different characteristics could have important implications for assessment, in that those with low levels of anxiety may have a tendency to underreport some of their behavioral difficulties. As these traits are being integrated into diagnostic criteria (Frick & Nigg, 2012), more research is needed to determine the optimal methods for assessing them in various samples. Along similar lines, it may also be important to consider the role of gender in the development of these traits, specifically with regard to its role in these distinct developmental pathways. While the current study found that the variants did not differ by gender, other research has found that empathy deficits in CU youth may vary for boys and girls (Dadds et al., 2009), the strength of genetic and environmental effects on CU traits may vary across gender (Fontaine, Rijsdijk, McCrory, & Viding, 2010), and the outcomes of children with CU traits may differ for boys and girls (Wymbs et al. 2012).

Also, the presumed differences in etiologies across the variants of youths with CU traits can shape hypotheses about targeted interventions for youths with these traits. Overall, a growing body of research indicates that intensive treatment can successfully reduce the severe conduct problems and aggression displayed by youths with CU traits (Kolko & Pardini, 2010; Waschbusch, Carrey, Willoughby, King, & Andrade, 2007). However, even greater gains may be possible if treatment targets the characteristics of the specific variants identified in this study. For example, research suggests that cognitive-behavioral interventions may be most effective at treating internalizing problems (e.g., anger, anxiety, and depression) and related trauma histories that distinguish secondary variants (Silverman, Pina, & Viswesvaran, 2008). For the low-anxious primary variant, recent research suggests that deficits in attention to others’ distress cues can at least temporarily be corrected by focusing youths’ attention on the eye region (Dadds et al., 2006). This group has also been shown to respond positively to rewards, suggesting another productive angle for progress in treatment (Hawes & Dadds, 2005). In summary, several promising interventions have emerged for youth with CU traits. These efforts are likely to be enhanced if they consider the heterogeneity among youth high on CU traits and appropriately tailor treatment to their individual needs.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by a grant from the National Institute of Health (R01 MH066647, PI: Youngstrom). Dr. Findling receives or has received research support, acted as a consultant and/or served on a speaker’s bureau for Alexza Pharmaceuticals, American Psychiatric Press, AstraZeneca, Bracket, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Clinsys, Cognition Group, Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, Guilford Press, Johns Hopkins University Press, Johnson & Johnson, KemPharm, Lilly, Lundbeck, Merck, NIH, Novartis, Noven, Otsuka, Pfizer, Physicians Postgraduate Press, Rhodes Pharmaceuticals, Roche, Sage, Seaside Pharmaceuticals, Shire, Stanley Medical Research Institute, Sunovion, Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Transcept Pharmaceuticals, Validus, and WebMD.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/pas

In our main analyses, we did not control for error rate due to multiple comparisons because we had specific theory-driven hypotheses and we wanted to emphasize effect sizes rather than significance levels. However, when applying Bonferonni correction, the results were largely unchanged. The only exceptions were that the secondary cluster was no longer higher on parent reported levels of impulsivity than the anxious-conduct group; the secondary cluster no longer differed from the primary cluster on parent reported levels of aggression; and the secondary cluster no longer differed from the primary cluster on measures of physical abuse.

References

- Achenbach TM, McConaughy SH, Howell CT. Child/Adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: Implication of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychological Bulletin. 1987;101:213–232. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.101.2.213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. University of Vermont; Burlington, VT: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Author; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett PA, Smith SS, Newman JP. Approach and avoidance motivation in psychopathic criminal offenders during passive avoidance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;72:1413–1428. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.72.6.1413. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.72.6.1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacher J, Wenzig K, Vogler M. SPSS TwoStep Clustering – A First Evaluation. In: van Dijkum Cor, Blasius Jörg, Durand Claire., editors. Recent Developments and Applications in Social Research Methodology. Proceedings of the RC33 Sixth International Conference on Social Science Methodology. Amsterdam; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Berger LM. Income, family characteristics, and physical violence toward children. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2005;29:107–133. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.02.006. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blagov PS, Patrick CJ, Lilienfeld SO, Powers AD, Phifer JE, Venables N, Cooper G. Personality constellations in incarcerated psychopathic men. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2011;4:293–315. doi: 10.1037/a0023908. doi:10.1037/a0023908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjørnebekk G. Psychometric properties of the scores on the behavioral inhibition and activation scales in a sample of Norwegian children. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2009;69:636–645. doi:10.1177/0013164408323239. [Google Scholar]

- Bjørnebekk G, Gjesme T. Future time orientation and temperament: Exploration of their relationship to primary and secondary psychopathy. Psychological Reports. 2009;105:275–292. doi: 10.2466/PR0.105.1.275-292. doi:10.2466/pr0.105.1.275-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke JD, Loeber R, Lahey BB. Adolescent conduct disorder and interpersonal callousness as predictors of psychopathy in young adults. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;36:334–346. doi: 10.1080/15374410701444223. doi:10.1080/15374410701444223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, White TL. Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:319–333. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.67.2.319. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu T, Fang D, Chen J, Wang Y, Jeris C. Proceedings of the 7th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 2001. 2001. A robust and scalable clustering algorithm for mixed type attributes in large database environment; pp. 263–268. [Google Scholar]

- Cleckley H. The mask of sanity: An attempt to reinterpret the so-called psychopathic personality. 1st ed. Oxford; England: 1941. [Google Scholar]

- Cleckley H. The mask of sanity. 5th ed. Mosby; St. Louis, MO: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Dadds MR, Hawes DJ, Frost ADJ, Vassallo S, Bunn P, Hunter K, Merz S. Learning to ‘talk the talk’: The relationship of psychopathic traits to deficits in empathy across childhood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50:599–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadds MR, Perry Y, Hawes D, Sabine M, Riddel AC, Haines DJ, Abeygunawardane A. Attention to the eyes and fear-recognition deficits in child psychopathy. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;189:280–281. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.018150. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.105.018150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Kazdin AE. Informant discrepancies in the assessment of childhood psychopathology: A critical review, theoretical framework, and recommendations for further study. Psychological Bulletin. 2005;131:483–509. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.4.483. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.131.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edens JF, Buffington JK, Tomicic TL. An investigation of the relationship between psychopathic traits and malingering on the Psychopathic Personality Inventory. Assessment. 2000;7:281–296. doi: 10.1177/107319110000700307. doi:10.1177/107319110000700307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edens JF, Cahill MA. Psychopathy in adolescence and criminal recidivism in young adulthood: Longitudinal results from a multiethnic sample of youthful offenders. Assessment. 2007;14:57–64. doi: 10.1177/1073191106290711. doi:10.1177/1073191106290711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edens JF, Campbell JS, Weir JM. Youth Psychopathy and criminal recidivism: A meta-analysis of the Psychopathy Checklist measures. Law and Human Behavior. 2007;31:53–75. doi: 10.1007/s10979-006-9019-y. doi:10.1007/s10979-006-9019-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkenbach D, Poythress N, Creevy C. The exploration of subclinical psychopathic subtypes and the relationship with types of aggression. Personality and Individual Differences. 2008;44:821–832. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2007.10.012. [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine NMG, Rijsdijk FV, McCrory EJP, Viding E. Etiology of different developmental trajectories of callous-unemotional traits. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49:656–664. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.03.014. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ. Extending the construct of psychopathy to youth: Implications for understanding, diagnosing, and treating antisocial children and adolescents. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;54:803–812. doi: 10.1177/070674370905401203. Retrieved from http://publications.cpa-apc.org/browse/documents/509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, Barry CT, Kamphaus RW. Clinical assessment of child and adolescent personality and behavior. 3rd edition Springer; New York: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, Bodin SD, Barry CT. Psychopathic traits and conduct problems in community and clinic-referred samples of children: Further development of the psychopathy screening device. Psychological Assessment. 2000;12:382–393. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.12.4.382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, Dickens C. Current perspectives on conduct disorder. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2006;8:59–72. doi: 10.1007/s11920-006-0082-3. doi:10.1007/s11920-006-0082-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, Hare RD. The Antisocial Process Screening Device (APSD) Multi-Health Systems; Toronto, Ontario: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, Nigg JT. Current issues in the diagnosis of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, Oppositional Defiant Disorder, and Conduct Disorder. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2012;8:77–107. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143150. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, Viding E. Antisocial behavior from a developmental psychopathology perspective. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:1111–1131. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409990071. doi:10.1017/S0954579409990071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, White SF. Research Review: The importance of callous unemotional traits for developmental models of aggressive and antisocial behavior. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;49:359–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01862.x. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller B, Zimerman B, Williams M, Bolhofner K, Craney JL, DelBello MP, Soutullo C. Reliability of the Washington University in St. Louis Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (WASH-U-KSADS) mania and rapid cycling sections. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:450–455. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00014. doi:10.1097/00004583-200104000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA. The psychology of fear and stress. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Hare RD, Hart SD, Harpur TJ. Psychopathy and the DSM-IV criteria for antisocial personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:391–398. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.3.391. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.100.3.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart SD, Hare RD. Psychopathy and risk assessment. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 1996;9:380–383. doi:10.1097/00001504-199603000-00007. [Google Scholar]

- Hart SD, Hare RD. Psychopathy: Assessment and association with criminal conduct. In: Stoff DM, Breiling J, Maser JD, editors. Handbook of antisocial behavior. Wiley; New York: 1997. pp. 22–35. [Google Scholar]

- Hart SD, Knopp PR, Hare RD. Performance of male psychopaths following conditional release from prison. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1988;56:227–232. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.2.227. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.56.2.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas SM, Waschbusch DA, Pelham WE, King S, Andrade BF, Carrey NJ. Treatment response in CP/ADHD children with callous/unemotional traits. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;4:541–552. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9480-4. doi:10.1007/s10802-010-9480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawes DJ, Dadds MR. The treatment of conduct problems in children with callous-unemotional traits. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:737–741. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.737. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemphill JF, Hare RD, Wong S. Psychopathy and recidivism: A review. Legal and Criminological Psychology. 1998;3:141–172. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8333.1998.tb00355.x. [Google Scholar]

- Hiatt KD, Lorenz AR, Newman JP. Assessment of emotion and language processing in psychopathic offenders: Results from a dichotic listening task. Personality and Individual Differences. 2002;32:1255–1268. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00116-7. [Google Scholar]

- Hicks BM, Markon KE, Patrick CJ, Krueger RF, Newman J. Identifying psychopathy subtypes on the basis of personality structure. Psychological Assessment. 2004;16:276–288. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.16.3.276. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.16.3.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hundt NE, Kimbrel NA, Mitchell JT, Nelson-Gray RO. High BAS, but not low BIS, predicts externalizing symptoms in adults. Personality and Individual Differences. 2008;44:565–575. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2007.09.018. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn RE, Frick PJ, Youngstrom EA, Findling RL, Kogos Youngstrom J. The effects of including a callous-unemotional specifier for the diagnosis of conduct disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2012;53:271–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02463.x. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02463.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpman B. On the need of separating psychopathy into two distinct clinical types. The symptomatic and the idiopathic. Journal of Criminology and Psychopathology. 1941;3:112–137. [Google Scholar]

- Karpman B. The myth of the psychopathic personality. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1948;104:523–534. doi: 10.1176/ajp.104.9.523. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.104.9.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Ryan N. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. doi:10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimbrel NA, Nelson-Gray RO, Mitchell JT. Reinforcement sensitivity and maternal style as predictors of psychopathology. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;42:1139–1149. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2006.06.028. [Google Scholar]

- Kimonis ER, Frick PJ, Cauffman E, Goldweber A, Skeem J. Primary and secondary variants of juvenile psychopathy differ in emotional processing. Development and Psychopathology. 2012;24:1094–1103. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412000557. doi:10.1017/S0954579412000557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimonis ER, Skeem JL, Cauffman E, Dmitrieva J. Are secondary variants of juvenile psychopathy more reactively violent and less psychosocially mature than primary variants? Law and Human Behavior. 2011;35:381–391. doi: 10.1007/s10979-010-9243-3. doi:10.1007/s10979-010-9243-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolko DJ, Pardini DA. ODD dimensions, ADHD, and callous-unemotional traits as predictors of treatment response in children with disruptive behavior disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119:713–725. doi: 10.1037/a0020910. doi:10.1037/a0020910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosson DS, Smith SS, Newman JP. Evaluating the construct validity of psychopathy in black and white inmates: Three preliminary studies. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1990;99:250–259. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.99.3.250. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.99.3.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurcharski TL, Scott D, Egan SS, Falkenbach DM. Psychopathy and malingering of psychiatric disorder in criminal defendants. Behavioral Sciences & the Law. 2006;24:633–644. doi: 10.1002/bsl.661. doi:10.1002/bsl.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leistico AR, Salekin RT, DeCoster J, Rogers R. A large-scale meta-analysis relating the Hare measures of psychopathy to antisocial conduct. Law and Human Behavior. 2008;32:28–45. doi: 10.1007/s10979-007-9096-6. doi:10.1007/s10979-007-9096-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Z, Salekin RT, Iselin AR. Psychopathic traits in youth: Is there evidence for primary and secondary subtypes? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2010;38:381–393. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9372-7. doi:10.1007/s10802-009-9372-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lykken DT. A study of anxiety in the sociopathic personality. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 1957;55:6–10. doi: 10.1037/h0047232. doi:10.1037/h0047232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lykken DT. The antisocial personalities. Earlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lynam DR, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Longitudinal evidence that psychopathy scores in early adolescence predict adult psychopathy. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:155–165. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.155. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March J. Manual for the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC) MultiHealth Systems; Toronto: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- March J. Assessment of pediatric Post-traumatic stress disorder. In: Saigh P, Bremner D, editors. Post-traumatic stress disorder: A comprehensive text. Allyn & Bacon, Inc.; Needham Heights, MA: 1999. pp. 199–218. [Google Scholar]

- March JS, Amaya-Jackson L, Murray MC, Shulte A. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for children and adolescents with post-traumatic stress disorder after a single incident stressor. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37:585–593. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199806000-00008. doi:10.1097/00004583-199806000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March JS, Amaya-Jackson L, Terry R, Costanzo P. Posttraumatic symptomatology in children and adolescents after an industrial fire. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:1080–1088. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199708000-00015. doi:10.1097/00004583-199708000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March J, Parker J, Sullivan K, Stallings P, Conners C. The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC): Factor structure, reliability and validity. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:554–565. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199704000-00019. doi:10.1097/00004583-199704000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran P, Rowe R, Flach C, Briskman J, Ford T, Maughan B, Goodman R. Predictive value of callous-unemotional traits in a large community sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48:1079–1084. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181b766ab. doi:10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181b766ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Meesters C, de Kanter E, Timmerman PE. Behavioural inhibition and behavioural activation system scales for children: relationships with Eysenck’s personality traits and psychopathological symptoms. Personality & Individual Differences. 2005;38:831–841. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2004.06.007. [Google Scholar]

- Newman JP, Schmitt WA. Passive avoidance in psychopathic offenders: A replication and extension. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:527–532. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.3.527. doi:10.1037//0021-843X.107.3.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman JP, MacCoon DG, Vaughn LJ, Sadeh N. Validating a distinction between primary and secondary psychopathy with measures of Gray’s BIS and BAS constructs. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:319–323. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.2.319. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.114.2.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman JP, Schmitt W, Voss W. The impact of motivationally neutral cues on psychopathic individuals: Assessing the generality of the response modulation hypothesis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:563–575. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.4.563. doi:10.1037//0021-843X.106.4.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally JC. Psychometric theory. 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Pardini DA, Fite PJ. Symptoms of conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and callous unemotional traits as unique predictors of psychosocial maladjustment in boys: Advancing an evidence base for DSM-V. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49:1134–1144. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.07.010. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardini DA, Lochman JE, Frick PJ. Callous/unemotional traits and social-cognitive processes in adjudicated youths. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42:364–371. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200303000-00018. doi:10.1097/00004583-200303000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piacentini JC, Cohen P, Cohen C. Combining discrepant diagnostic information from multiple sources: Are complex algorithms better than simple ones? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1992;20:51–63. doi: 10.1007/BF00927116. doi:10.1007/BF00927116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poythress NG, Skeem JL, Douglas KS, Patrick CJ, Edens JF, Lilienfeld SO, Wang T. Identifying subtypes among offenders with antisocial personality disorder: A cluster-analytic study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119:389–400. doi: 10.1037/a0018611. doi:10.1037/a0018611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]