Abstract

Background:

Chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalitis (CFS/ME) is rarely diagnosed in South Asia (SA), although the symptoms of this condition are seen in the population. Lessons from UK based South Asian, Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) communities may be of value in identifying barriers to diagnosis of CFS/ME in SA.

Objectives:

To explore why CFS/ME may not be commonly diagnosed in SA.

Settings and Design:

A secondary analysis of qualitative data on the diagnosis and management of CFS/ME in BME people of predominantly South Asian origin in the UK using 27 semi-structured qualitative interviews with people with CFE/ME, carers, general practitioners (GPs), and community leaders.

Results:

CFS/ME is seen among the BME communities in the UK. People from BME communities in the UK can present to healthcare practitioners with vague physical complaints and they can hold a biomedical model of illness. Patients found it useful to have a label of CFS/ME although some GPs felt it to be a negative label. Access to healthcare can be limited by GPs reluctance to diagnose CFS/ME, their lack of knowledge and patients negative experiences. Cultural aspects among BME patients in the UK also act as a barrier to the diagnosis of CFS/ME.

Conclusion:

Cultural values and practices influence the diagnosis of CFS/ME in BME communities. The variations in the perceptions around CFS/ME among patients, carers, and health professionals may pose challenges in diagnosing CFS/ME in SA as well. Raising awareness of CFS/ME would improve the diagnosis and management of patients with CFS/ME in SA.

Keywords: Access to care, Asian/Black and ethnic minority, chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalitis, primary care

Introduction

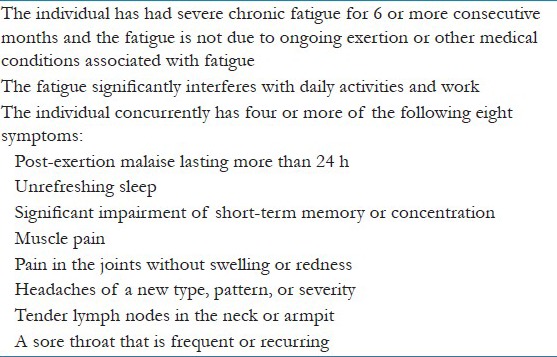

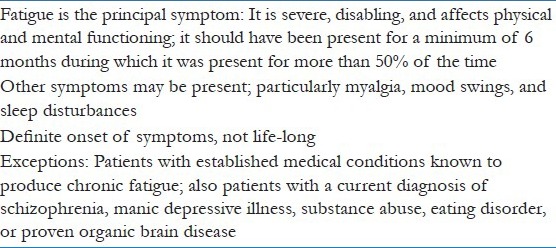

Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) or myalgic encephalitis (ME) is characterized by severe, disabling, medically unexplained fatigue that is not alleviated by rest and lasts for at least 6 months [Tables 1 and 2].[1,2] CFS/ME causes high levels of disability and burden to affected individuals, families, and society; and is associated with high economic costs in the UK.[3,4] The National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) guideline for CFS/ME in England for CFS/ME emphasizes the importance of confident diagnosis in primary care, starting treatment early, and working in partnership with people with CFS/ME to manage the condition.[2]

Table 1.

Centers for disease control and prevention (CDC) criteria for diagnosing CFS/ME (1994) – includes three criteria

Table 2.

The Oxford criteria for diagnosing chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalitis (CFS/ME) (1991)

The population prevalence of CFS/ME in UK has been estimated to be 0.2-0.4%,[5] and recent research suggests that the prevalence of CFS/ME may be higher for some minority ethnic groups than for White people in the UK.[6] Research on CFS/ME is mostly available from the US and the UK, and data from the East is scarce. The prevalence of disabling fatigue from a World Health Organization (WHO) multinational study, including South Asia (SA) was found to be 1.69%,[7] and a community study among women in India revealed that chronic fatigue was seen in 1 in 10 women, although the prevalence of CFS/ME is not known.[8] A study carried out among Chinese people in Hong Kong also revealed that the estimated prevalence of CFS/ME was 10.7%.[9] The point prevalence of CFS/ME is reported to be between 0.6 and 8.4% in Korea.[10] CFS/ME is considered part of the spectrum of medically unexplained symptoms (MUS) and MUS are among the common clinical presentations in primary care in developing countries.[11]

CFS/ME can lack recognition as a significant illness for its sufferers, and patients report that their fatigue symptoms and their impact are not taken seriously by health professionals.[12] In a recent primary care treatment trial in the UK,[13] the mean time from onset of symptoms to diagnosis was 3.6 years. In the UK it is reported that general practitioners (GPs) lack understanding of CFS/ME and its management,[14,15] therefore it is possible that patients may be presenting to doctors in SA with symptoms of CFS/ME, but it is not being diagnosed or appropriately managed.

This paper uses secondary analysis of a data set which aimed to explore making the diagnosis and managing CFS/ME in the UK, from the perspectives of patients, carers, community leaders, and primary care practitioners. One focus of the original study was to explore the barriers to the diagnosis of CFS/ME in people from UK based South Asian and Black and Minority Ethnic communities in the UK; thus, it is intended that secondary analysis will help to understand why CFS/ME may not be commonly diagnosed in SA.

Materials and Methods

The study reported is a secondary analysis of qualitative data on diagnosis and management of CFS/ME in the North West England.[16] Secondary analysis involves the utilization of existing data in order to pursue a research interest which is distinct from that of the original work.[17,18] The current study focuses on the CFS/ME in BME people of predominantly South Asian origin living in the UK to ascertain patients’, carers’, community leaders’, and GP's perceptions of CFS/ME. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Greater Manchester East Ethics Committee, and the study was carried out in accordance with the ethical standards of the committee.

Data

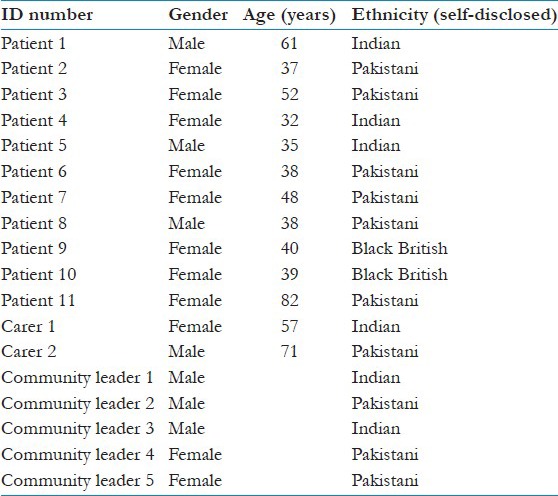

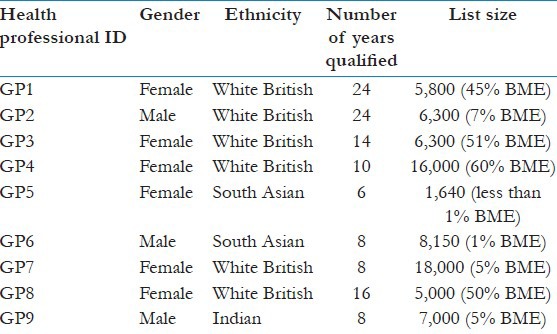

Data were collected during 2011-2012. A purposive sample of BME patients, carers, GPs, and community leaders were recruited for the study [Tables 3 and 4]. All interviews were digitally audiotaped with consent and were transcribed verbatim.

Table 3.

Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) patient, carer, and community leader demographics

Table 4.

General practitioner details

Analysis

A new analytic framework was developed on “culture and barriers to diagnosis”. The secondary researcher was naive to original research findings. The process of refinement and validation of findings was conducted through a collaborative exercise creating feedback loops between the secondary researcher and the primary researchers. Further discussion between authors resulted in the identification of themes specifically relevant to BME patients presented in this paper.

Results

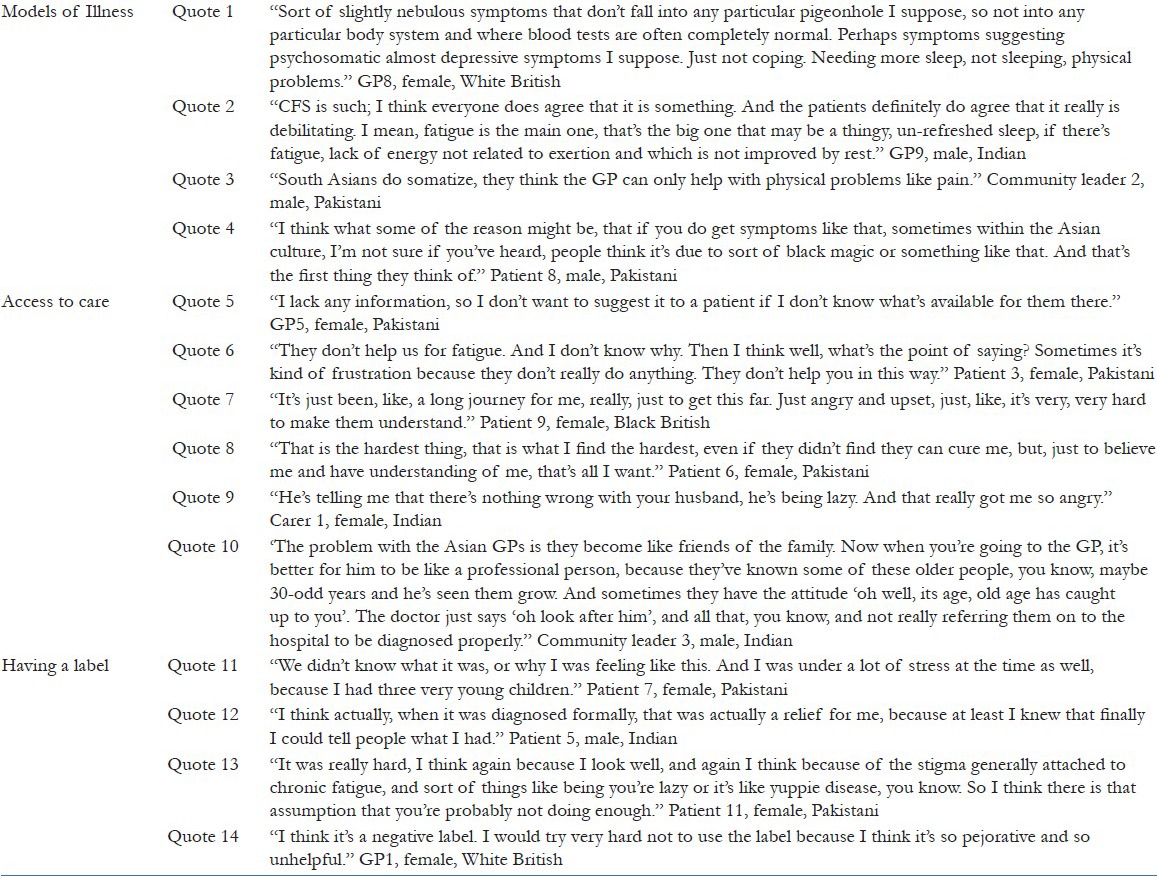

Data are presented in three key themes, models of illness, access to care, and having a label. Data will be presented to support the analysis, and is identified by participant code [Table 5].

Table 5.

Quotes of general practitioners (GPs), Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) patients, carers, and community leaders

Models of illness

Patients and community leaders suggested that health professionals might focus on physical symptoms and patients may not be encouraged to discuss nonspecific symptoms such as fatigue. The majority of GPs described CFS/ME as a set of symptoms which they found hard to understand, but alluded to a ‘biopsycho-social’ etiology and impacting on function. [Table 4, (Quotes 1 and 2)].

GPs suggested that patients of BME origin hold a biomedical model of illness, and that they present with vague physical complaints, with somatization being more common. GPs reported that culturally BME communities do not consider tiredness or fatigue as a symptom that requires medical assistance, instead other physical symptoms are reported.

Some patients suggested that their symptoms might be attributed in their cultures to black magic, thus patients may consult a spiritual healer rather than go to the GP (Quotes 3 and 4).

Access to care

Some GPs described uncertainty and unwillingness to make a diagnosis of CFS/ME, attributing this to their own lack of knowledge about CFS/ME and its management. CFS/ME was described as a diagnosis of exclusion, a difficult diagnosis to make, but also as a negative label which might mean patients cannot improve (Quote 5).

Many patients and carers reported negative experiences of consulting GPs about their symptoms of CFS/ME, and they had chosen not to consult in the future (Quote 6). Patients reported having waited a considerable time before a diagnosis of CFS/ME was achieved (Quote 7).

Patients of BME origin described the importance of being believed and taken seriously by their healthcare professionals, and they described how difficult it had been to convince the GPs of their symptoms (Quotes 8 and 9).

BME patients and community leaders described how GPs who were family friends or part of the community might be less likely to suggest a diagnosis of CFS/ME, and this can contribute to patients not seeking a medical opinion (Quote 10).

Having a label

Patients described how important it is to have a diagnosis or label, as this can legitimate their symptoms and help them to understand and cope with their illness. The lack of a label can be stressful to them as well as their families (Quote 11) and the diagnosis provides an explanation they could communicate to other people, their family, friends, and employers (Quote 12).

Some patients, however, suggested that the stigma attached to the label of CFS/ME can make it more difficult to accept. Community leaders described how people with CFS/ME could be given stigmatizing labels such as ‘lazy’, ‘liars’, or ‘crazy’ by their community and BME patients may therefore want to avoid this potentially stigmatizing diagnosis (Quote 13).

Many GPs stated that CFS/ME is a negative label as they lacked knowledge on the management of CFS/ME, which they felt, would lead to lack of hope for recovery in the patient (Quote 14).

Discussion

Summary of results

CFS/ME is seen among the BME communities of predominantly South Asian origin in the UK, and is also reported in some Asian countries. However, even in the UK, CFS/ME is recognized and diagnosed only by some GPs, while others fail to make a diagnosis. This may be seen in SA as well, where healthcare professionals are not recognizing CFS/ME and therefore patients may be labeled as ‘somatizers’.

This study suggests people from BME communities report only consulting with their GP for physical symptoms. Some GPs in this study reported not being comfortable in making a diagnosis of CFS/ME, and they described lacking knowledge about CFS/ME. Patients and carers reported negative experiences of consulting GPs when the GP is skeptical about the condition, resulting in access to healthcare being negatively affected. Patients have had symptoms of CFS/ME for a long duration before they were diagnosed with CFS/ME. Patients reported they require a label although some GPs who lacked knowledge on the management of CFS/ME stated CFS/ME to be a negative label.

Comparison with the literature

Evidence suggests that health professionals can hold a “somatization” model of illness where patients are thought to be expressing social and emotional problems in physical symptoms.[19] A community study in India revealed that women with chronic fatigue were more likely to report other physical symptoms and that the rates of chronic fatigue lasting for at least 6 months to be similar to or higher than those reported from developed countries.[8] This was also seen in our study where GPs reported that patients tended to present with other physical symptoms. Although MUSs are among the most common causes of morbidity in developing countries,[11] these complaints tend to be associated with multiple other complains specially among the poor.[20]

Patients report benefiting from a label as this enables them to discuss their illness with their families, places of work, and colleagues; which may improve understanding of the condition. However, access to care for people with CFS/ME is limited, acting as a barrier to early diagnosis of CFS/ME even in countries where it is recognized with accepted guidelines for patient care. Previous studies in the UK, also report that GPs felt that current training and education failed to prepare them for diagnosing and managing patients with CFS/ME in the way recommended by current guidelines.[14,21] Guise et al., report that patients describe themselves as experiencing limited medical care and attention.[22] Candidacy describes the ways in which people's eligibility for medical attention and intervention is jointly negotiated between individuals and health services,[23] thus disadvantaged people may have barriers in experiencing healthcare. The concept of recursivity, describes how the response of the system to individuals may reinforce or discourage future health behaviors.[23,24] Self-evaluation of the symptoms of fatigue left patients and their families unsure of whether it was appropriate to consult, thus not possessing candidacy[25] and reluctance of GPs to make a diagnosis and patients’ negative experiences can act recursively to become a barrier to access to future healthcare.

Strengths and limitations of the study

A strength of this study is that a range of stakeholders; including patients, carers, community leaders, and GPs were interviewed to provide insights into the barriers faced in both obtaining and providing a diagnosis of CFS/ME in BME groups in the UK. This is valuable data as this group is often hard to reach due to language and cultural barriers.

The BME participants in this study were South Asian and Black British. Results cannot be generalized from these data as there will be differences within and between BME groups. It is also important to recognize that not all the findings are unique to BME groups. However, the participants in this study describe how such barriers can be exaggerated in BME groups. Study carried out in one geographical area in England therefore may not be generalizable to SA.

Implications for clinical practice, teaching, and training

The variations in the perceptions around CFS/ME among patients, carers, and GPs may pose challenges in diagnosing CFS/ME in SA as seen in similar communities in the UK. It is important to raise awareness of patients with MUS such as CFS/ME in SA in order to encourage patients to seek healthcare. Lack of continuity in care can also act as a barrier in diagnosing CFS/ME as patients may present to different healthcare practitioners thus delaying the diagnosis of CFS/ME.

This study also highlights the importance of training of healthcare professionals to be aware of symptoms of CFS/ME, cultural aspects affecting presentation, and be sensitive to the needs of patients with CFS/ME.

Future research directions

Further research to understand patient, community, and healthcare practitioner beliefs; and experiences in CFS/ME and other MUSs will be of value, in developing a culturally sensitive consultation model and in improving the diagnosis of CFS/ME in SA.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the patients, carers, community leaders, and GPs who agreed to be interviewed as part of the METRIC study and Louise Fisher our academic clinical fellow, who conducted qualitative interviews with healthcare professionals. R. E. Ediriweera de Silva wishes to thank the Institute of Population Health, University of Manchester for accommodating her as a visiting academic for a period of 11 months during the course of the study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: The METRIC (ME Education, Training and Resources for Primary Care) study is funded by the National Institute for Health Research, under the UK Research for Patient Benefit (RfPB) grant. The views expressed are those of the author (s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Prins JB, van der Meer JW, Bleijenberg G. Chronic fatigue syndrome. Lancet. 2006;367:346–55. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68073-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (or encephalopathy): Diagnosis and management of CFS/ME in adults and children. NHS National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. NICE Clinical Guideline. 2007;7:53. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collin SM, Crawley E, May MT, Sterne JA, Hollingworth W. UK CFS/ME National Outcomes Database. The impact of CFS/ME on employment and productivity in the UK: A crosssectional study based on the CFS/ME national outcomes database. [Last accessed on 2012 Dec 5];BMC Health Serv Res. 2011 11:217. Available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/11/217 . [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sabes-Figuera R, McCrone P, Hurley M, King M, Donaldson AN, Ridsdale L. The hidden cost of chronic fatigue to patients and their families. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:56. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Department of Health. Independent working group: A report of the CFS/ME working group. Report to the Chief Medical Officer of an independent working group. London. DH. 2002. [Last accessed on 2012 Sep 18]. Available from: http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_4064945.pdf .

- 6.Dinos S, Khoshaba B, Ashby D, White PD, Nazroo J, Wessely S, et al. A systematic review of chronic fatigue, its syndromes and ethnicity: prevalence, severity, co-morbidity and coping. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38:1554–70. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skapinakis P, Lewis G, Mavreas V. Unexplained fatigue syndromes in a multinational primary care sample: Specificity of definition and prevalence and distinctiveness from depression and generalized anxiety. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:785–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.4.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel V, Kirkwood BR, Weiss H, Pednekar S, Fernandes J, Pereira B, et al. Chronic fatigue in developing countries: Population based survey of women in India. BMJ. 2005;330:1190. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38442.636181.E0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong WS, Fielding R. Prevalence of chronic fatigue among Chinese adults in Hong Kong: A population-based study. J Affect Disord. 2010;127:248–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim CH, Shin HC, Won CW. Prevalence of chronic fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome in Korea: Community-based primary care study. J Korean Med Sci. 2005;20:529–34. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2005.20.4.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel V, Sumathipala A. Psychological approaches to somatization in developing countries. Adv Psychiatric Treat. 2006;12:54–62. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whitehead L. Ph.D. Thesis. University of Liverpool; 2004. The lived experience of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME): Sufferers’ and families’ perspectives. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wearden AJ, Dowrick C, Chew-Graham C, Bentall RP, Morriss RK, Peters S, et al. Fatigue Intervention by Nurses Evaluation (FINE) trial writing group and the FINE trial group. Nurse led, home based self help treatment for patients in primary care with chronic fatigue syndrome: Randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c1777. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chew-Graham C, Dowrick C, Wearden A, Richardson V, Peters S. Making the diagnosis of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalitis in primary care: A qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2010;11:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-11-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raine R, Carter S, Sensky T, Black N. General practitioners’ perceptions of chronic fatigue syndrome and beliefs about its management, compared with irritable bowel syndrome: Qualitative study. BMJ. 2004;328:1354–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38078.503819.EE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hannon K, Peters S, Fisher L, Riste L, Wearden A, Lovell K, et al. Developing resources to support the diagnosis and management of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalitis (CFS/ME) in primary care. A qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13:93. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-13-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Szabo V, Strang VR. Secondary analysis of qualitative data. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 1997;20:66–74. doi: 10.1097/00012272-199712000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van den Berg H. Reanalyzing qualitative interviews from different angles: The risk of decontextualization and other problems of sharing qualitative data. [Last accessed on 2013 Aug 19];Forum Qual Soc Res. 2005 6:30. Availbale from: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0501305 . [Google Scholar]

- 19.Asbring P, Narvanen AL. Ideal verses reality: Physicians’ perspectives on patients with chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) and fibromyalgia. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57:711–20. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00420-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization: The World Health Report -Mental Health New Understanding, New Hope. WHO Library Cataloguing in Publication Data; The World health report. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chew-Graham CA, Cahill G, Dowrick C, Wearden A, Peters S. Using multiple sources of knowledge to reach clinical understanding of chronic fatigue syndrome. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:340–8. doi: 10.1370/afm.867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guise J, McVittie C, McKinlay A. A discourse analytic study of ME/CFS (Chronic Fatigue Syndrome) suffers’ experiences of interactions with doctors. J Health Psychol. 2010;15:426–35. doi: 10.1177/1359105309350515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.UK: National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health; [Last accessed on 2013 Jan 22]. Common Mental Health Disorders: Identification and Pathways to Care. NICE Clinical Guidelines, No. 123. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK92265 . [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rogers A, Hassell K, Nicolaas G. Buckingham: Open University; 1999. Demanding Patients: Analysing the Use of Primary Care. The State of Health series. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dixon-Woods M, Cavers D, Agarwal S, Annandale E, Arthur A, Harvey J, et al. Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6:35. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-6-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]